Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label nicaragua .

[Scott Martelle, William Walker's Wars. How One Man's Private Army Tried to Conquer Mexico, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Chicago Review Press. Chicago, 2019. 312 p.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

The history of US interference in Latin America is long. In plenary session of the Executive Council Manifest Destiny of westward expansion in the mid-19th century, to extend the country from coast to coast, there were also attempts to extend sovereignty to the South. Those who occupied the White House were satisfied with half of Mexico, which completed a comfortable access to the Pacific, but there were personal initiatives to attempt to purchase and even conquer Central American territories.

The history of US interference in Latin America is long. In plenary session of the Executive Council Manifest Destiny of westward expansion in the mid-19th century, to extend the country from coast to coast, there were also attempts to extend sovereignty to the South. Those who occupied the White House were satisfied with half of Mexico, which completed a comfortable access to the Pacific, but there were personal initiatives to attempt to purchase and even conquer Central American territories.

One such initiative was led by William Walker, who, at the head of several hundred filibusters - the American Phalanx - seized the presidency of Nicaragua and dreamed of a slave empire that would attract investment from American Southerners if slavery was abolished in the United States. Walker, from Tennessee, first tried to create a republic in Sonora, to integrate that Mexican territory into the US, and then focused his interest on Nicaragua, then an attractive passage for Americans who wanted to cross the Central American isthmus to the gold mines of California, where he himself had sought his fortune. Disallowed and detained several times by the US authorities, due to the problems he caused them with neighbouring governments, he was finally expelled from Nicaragua by force of arms and shot dead while trying to return by setting foot in Honduras.

Scott Martelle's book is both a portrait of the character - someone with no special leadership skills and a rather delicate appearance unbefitting a mercenary chief, who nevertheless managed to generate lucrative expectations among those who followed him (2,518 Americans enlisted) - and a chronicle of his military campaigns in the South of the United States. It also describes well the mid-19th century atmosphere in cities such as San Francisco and New Orleans, filled with migrants from other parts of the country and in transit to wherever fortune would take them.

It also provides a detailed account of the business developed by the tycoon Vanderbilt to establish a route, inaugurated in 1851, which used the San Juan River to reach Lake Nicaragua and from there to the Pacific, with the aim of establishing a railway connection and the subsequent purpose to build a canal in a few years. Although the overland route was longer than the one that at that time was also being made under similar conditions on the Isthmus of Panama, the journey by boat from the USA to Nicaragua was shorter than the one that required going all the way to Panama. The latter explains why, during the second half of the 19th century, the project Nicaragua Canal had more supporters in Washington than the Panama Canal.

While Panama is one of the symbols of US interference in its "backyard", the success of the transoceanic canal project and its return to the Panamanians largely defuses a "black legend" that still exists in the Nicaraguan case. Nicaragua is probably the Central American country that has experienced the most US "imperialism". The Walker episode (1855-1857) marks a beginning, followed by the US government's own military interventions (1912-1933), Washington's close support for the Somoza dictatorship (1937-1979) and direct involvement in the fight against the Sandinista Revolution (1981-1990).

Walker arrived in Nicaragua, attracted by US interest in the inter-oceanic passage and with the excuse of helping one of the sides in one of the many civil wars between conservatives and liberals in the former Spanish colonies. Elevated to head of the army, in 1856 he was elected president of a country in which he could barely control the area whose centre was the city of Granada, on the northern shore of Lake Nicaragua.

As he established his power he moved away from any initial idea of integrating Nicaragua into the US and dreamed of forging a Central American empire that would even include Mexico and Cuba. Slavery, which had been abolished in Nicaragua in 1838 and reinstated by him in 1856, entered into his strategy. He envisioned it as a means of preventing Washington from giving up extending its sovereignty to those territories, given the internal balances in the US between slave and non-slave states, and as an attraction of capital from southern slaveholders. He was finally expelled from the country in 1857 thanks to the push of an army assembled by neighbouring countries. In 1860 he attempted a return, but was captured and shot in Trujillo (Honduras). His adventure was fuelled by a belief in the superiority of the white, Anglo-Saxon man, which led him to despise the aspirations of the Hispanic peoples and to overestimate the military capacity of their mercenaries.

Martelle's book responds more to a historicist than a popularising purpose , so it is not so much for the general public as for those specifically interested in William Walker's Fulibusterism: an episode, in any case, of convenient knowledge on the Central American past and the relationship of the United States with the rest of the Western Hemisphere.

Central America's Northern Triangle migrants look to the U.S., Nicaragua's to Costa Rica

While migrants from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras continue to try to reach the United States, those from Nicaragua have preferred to travel to Costa Rica in recent years. The restrictions put in place by the Trump Administration and the deterioration of the Costa Rican economic boom are reducing the flows, but this migratory divide in Central America remains for the time being.

▲Belize-Mexico border crossing [Marrovi/CC].

article / Celia Olivar Gil

When comparing the Degree of development of the Central American countries, the different human flows operating in the region are well understood. The United States is the great migratory magnet, but Costa Rica is also to some extent a pole of attraction, evidently to a lesser extent Degree. Thus, the five Central American countries with the highest poverty rates -Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Belize- share their migratory orientation: the first four maintain important flows to the United States, while in recent years Nicaragua has opted more for Costa Rica, given its proximity.

Migration from the Northern Triangle to the U.S.

Nearly 500,000 people try every year to cross Mexico's southern border with the goal to reach the United States. Most of them come from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, the Central American region known as the Northern Triangle, which is currently one of the most violent in the world. The reasons that lead this high issue number of citizens from the Northern Triangle to migrate, many illegally, are various:

On the one hand, there are reasons that could be described as structural: the porousness of the border, the complexity and high costs of regularization processes for migration, the lack of commitment by employers to regularize migrant workers, and the insufficient capacity of governments to establish migration laws.

There are also clear economic reasons: Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador have high poverty rates, at 67.7%, 74.3% and 41.6%, respectively, of their inhabitants. presentation Difficulties in budgetary income and pronounced social inequality mean that public services, such as Education and healthcare, are deficient for a large part of the population.

Perhaps the most compelling reason is the lack of security. Many of those leaving these three countries cite insecurity and violence as the main reason for their departure. The level of criminal violence in the Northern Triangle reaches levels similar to those of an armed conflict. In El Salvador, a total of 6,650 intentional homicides were registered in 2015; in Honduras, 8,035, and in Guatemala, 4,778.

All these reasons push Guatemalans, Salvadorans and Hondurans to migrate to the United States, who on their journey north use three main routes to cross Mexico: the one that crosses the country diagonally until reaching the area of Tijuana, the one that advances through central Mexico to Ciudad Juarez and the one that seeks to enter the US through the Rio Bravo valley. subject Along these routes, migrants face many risks, such as falling victim to criminal organizations and suffering all kinds of abuses (kidnapping, torture, rape, robbery, extortion...), which can not only cause immediate physical injuries and trauma, but can also leave serious long-term consequences deadline.

Despite all these difficulties, citizens of the Northern Triangle continue to choose the United States as their migration destination. This is mainly due to the attraction of the economic potential of a country like the USA, at status of plenary session of the Executive Council employment ; to its relative geographic proximity (it is possible to arrive by land crossing only one or two countries), and to the human relations created since the 1980s, when the USA began to be goal for those fleeing the civil wars of a politically unstable Central America with economic difficulties, which created a migratory tradition, consolidated by family connections and the protection offered to the newcomers by the already established nationals. During this period, the Central American population in the U.S. tripled. Today, 82.9% of Central American immigrants in the U.S. live in the United States.

|

The American immigration 'watershed' [with ABC's authorization]. |

Migration from Nicaragua to Costa Rica

If emigration from northern Central America has been directed towards the United States, emigration from southern Central America has had more destinations. If Hondurans have looked to the north, in recent years their Nicaraguan neighbors have looked somewhat more to the south. The Coco River, which divides Honduras and Nicaragua, has become a sort of migratory'watershed'.

Certainly there are more Nicaraguans officially residing in the U.S. (over 400,000) than in Costa Rica (close to 300,000), but in recent years the issue of new residents has increased more in Costa Rican territory. In the last decade, from agreement with an OAS report (pages 159 and 188), the US has granted permanent residency program permission to a average of 3,500 Nicaraguans each year, while Costa Rica has granted about 5,000 from average, reaching a record 14,779 in 2013. Moreover, the proportional weight of Nicaraguan migration in Costa Rica, a country of 4.9 million inhabitants, is large: in 2016, some 440,000 Nicaraguans entered the neighboring country, and as many exits were recorded, indicating a significant cross-border mobility and suggesting that many workers temporarily return to Nicaragua to circumvent the requirements de extranjería.

Costa Rica is seen in certain aspects in Latin America as Switzerland in Europe, that is, as an institutionally solid, politically stable and economically favorable country. This means that the emigration of Costa Ricans is not extreme and that people come from other places, so that Costa Rica is the country with the highest net migration in Latin America, with 9% of the Costa Rican population of foreign origin.

Since its independence in the 1820s, Costa Rica has remained one of the Central American countries with the least amount of serious conflicts. For this reason, during the 1970s and 1980s it was a refuge for many Nicaraguans fleeing the Somoza dictatorship and the Sandinista revolution. Now, however, they do not emigrate for security reasons, since Nicaragua is one of the least violent countries in Latin America, even below Costa Rica's figures. This migratory flow is due to economic reasons: Costa Rica's higher development is reflected in the poverty rate, which is 18.6%, compared to Nicaragua's 58.3%; in fact, Nicaragua is the poorest country in the Americas after Haiti.

Likewise, Nicaraguans have a special preference for choosing Costa Rica as a destination because of its geographic proximity, which allows them to move frequently between the two countries and to maintain to a certain extent family coexistence; the use of the same language, and other cultural similarities.

The Russian positioning system GLONASS has placed ground stations in Brazil and Nicaragua; the different accessibility of them to nationals gives rise to conjectures

At a time when Russia has declared its interest in having new military facilities in the Caribbean, the opening of a Russian station in the Managua area has raised some suspicions. Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, has opened four stations in Brazil, managed with transparency and easy access; instead, the one that has built in Nicaragua is surrounded by secrecy. What little is known about the Nicaraguan station, strangely greater than the others, contrasts with the openly that data can be collected on the Brazilians.

ARTICLE / Jakub Hodek [English version].

We know that information is power. The more information you have and manage, the more power you enjoy. This approach must be taken into account when examining the ground stations that serve to support the Russian satellite navigation system and its construction in relative proximity to the United States. Of course we are no longer in the Cold War period, but some of the traumas of those old times may help us to better understand the cautious position of the United States and the importance that Russia sees in having its facilities in Brazil and especially in Nicaragua.

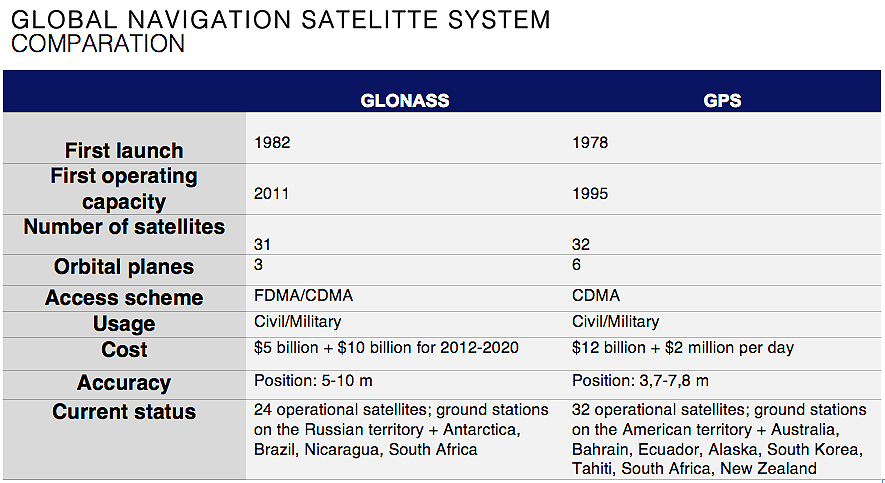

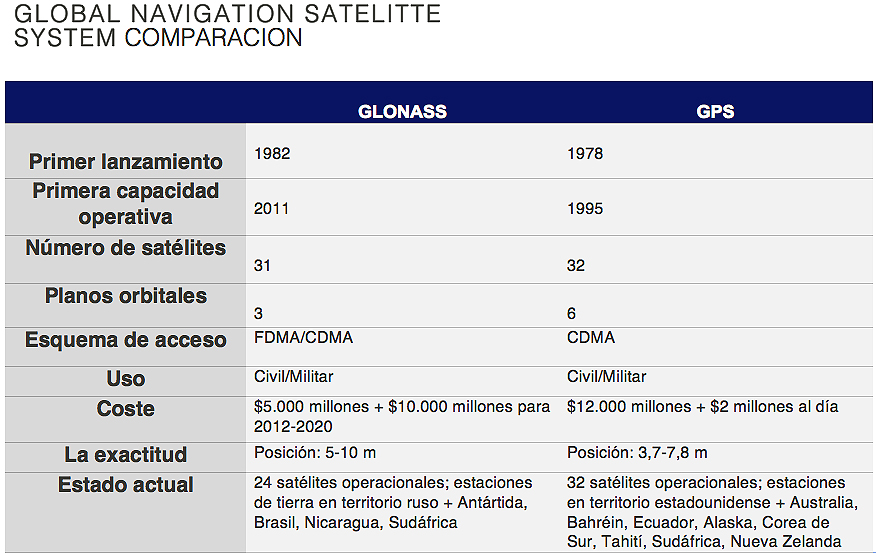

That historical background of the Cold War is at the origin of the two largest navigation systems we use today. The United States launched the Global Positioning System (GPS) project in the year 1973, and possibly in response, the Soviet Union presented its own positioning System (GLONASS) three years later. [ 1] It has been almost 45 years, and these two systems no longer serve Russians and Americans to try to get information on each other, but are collaborating and thus offering a more accurate and fast navigation system for consumers who buy a Smartphone or other electronic device. [2]

However, in order to achieve global coverage, both systems need not only satellites, but also ground stations strategically distributed around the world. For that purpose, the Russian Federal Space Agency, Roscosmos has erected stations for the GLONASS system in Russia, Antarctica and South Africa, as well as in the Western Hemisphere: it has four stations in Brazil and since April 2017 has one in Nicaragua, which by secrecy around its purpose has caused mistrust and suspicion in the United States [3] (USA, for its part, has ground stations for GPS in its territory and Australia, Argentina, United Kingdom, Bahrain, Ecuador, South Korea, Tahiti, South Africa and New Zealand).

The Russian Global Satellite Navigation System (Globalnaya Navigatsionnaya Sputnikovaya Sputnikovaya sistema or GLONASS) is a positioning system operated by the Russian Aerospace Defence Forces. It consists of 28 satellites, allowing real-time positioning and speed data for the surface, sea and airborne objects around the world. [ 4] In principle GLONASS does not transmit any personally identifiable information; in fact, user devices only receive signals from satellites, without transmitting anything back. However, it was originally developed with military applications in mind and carries encrypted signals that are supposed to provide higher resolutions to authorized military users (same as the US GPS). [5]

|

In Brazil, there are four Earth stations that are used to track signals from the GLONASS constellation. These stations serve as correction points in the Western hemisphere and help significantly improve the accuracy of navigational signals. Russia is in close and transparent collaboration with the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB), promoting research and development of the aerospace sector of this South American country. In 2013 the first station was installed, located on the campus of the University of Brasilia, which was also the first Russian station of that type abroad. It followed another station in the same place in 2014, and later, in 2016, a third was put in the Federal Institute of Sciences of the education and technology of Pernambuco, in Recife. The Russian Federal Space agency Roscosmos built its fourth Brazilian station on the territory of the Federal University of Santa Maria, in Rio Grande do Sul. In addition to fulfilling its main purpose of increasing accuracy and improving the performance of GLONASS, the facilities can be used by Brazilian scientists to carry out other types of scientific research. [6]

The level of transparency that surrounded the construction and then has prevailed in the management of the stations in Brazil is definitely not the same as the one applied in Managua, the capital of Nicaragua. There are several information that create doubts regarding the true use of the station. For starters, there is no information about the cost of the facilities or about the specialization of the staff. The fact that the station has been put at a short distance from the U.S. Embassy has given rise to conjecture about its use for phone-tapping and spying.

In addition, the vague replies from the representatives of Nicaragua and Roscosmos about the use of the station, have not managed to transmit confidence in the project. It is a "strategic project" for both Nicaragua and Russia, concluded Laureano Ortega, the son of the Nicaraguan president. Both countries claim to have very fluid and close cooperation in many areas, such as in health and development projects. However, none of those collaborations have materialized with such speed and dedication as this particular project. [7]

Given Russia's larger military presence in Nicaragua, empowered by the agreement that facilitates the mooring of Russian warships in Nicaragua announced by Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu during his visit to the Central American country in February 2015, and specified also in the donation of 50 T-72B1 Russian tanks in 2016 and the increased movement of the Russian military personnel, it can be concluded that Russia clearly sees strategic importance in its presence in Nicaragua. [ 8] [ 9] This is all observed with suspicion from America. The head of South American Command, Kirt Tidd, warned in April that "the Russians are moving forward a disturbing attitude" in Nicaragua, which "impacts the stability of the region."

Without a doubt, when world powers like Russia or the United States act outside their territory, they are always guided by a combination of motivations. Strategic positioning is essential in the game of world politics. For this very reason, the aid that a country receives or the collaboration it can establish with a great power is often subject to political conditionality.

In this case, it is difficult to know for sure what is the purpose of the station in Nicaragua or even those of Brazil. At first glance, the objective seems neutral - offering higher quality navigation system and providing a different option to GPS -, but given the new importance that Russia is granting to its geopolitical capabilities, there is the possibility of more strategic use.

Russia's GLONASS positioning system has placed ground stations in Brazil and Nicaragua; the Brazilian ones are accessible, but the Nicaraguan one is open to conjecture.

At a time when Russia has declared its interest in having military installations in the Caribbean again, the opening of a Russian station in Managua's area has raised some suspicions. Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, has opened four stations in Brazil, managed with transparency and easy access; in contrast, the one it has built in Nicaragua is shrouded in secrecy. The little that is known about the Nicaraguan station, strangely larger than the others, contrasts with how openly data can be collected about the Brazilian ones.

article / Jakub Hodek [English version].

It is well known that information is power. The more information one has and manages, the more power one enjoys. This approach should be taken when examining the station facilities that support the Russian satellite navigation system and their construction in close proximity to the United States. Of course, we are no longer in the Cold War period, but some traumas of those old days can perhaps help us to better understand the cautious position of the United States and the importance Russia sees in having its facilities in Brazil and especially in Nicaragua.

That historical background of the Cold War is at the origin of the two major navigation systems we use today. The United States launched the Global Positioning System (GPS) project in 1973, and possibly in response, the Soviet Union introduced its own positioning system (GLONASS) three years later. [1] Nearly 45 years have passed, and these two systems are no longer serving as a means for Russians and Americans to try to obtain information about the opposing side, but are collaborating and thus providing a more accurate and faster navigation system for consumers who purchase a smartphone or other electronic device. [2]

However, to achieve global coverage both systems need not only satellites, but also ground stations strategically located around the world. With that purpose, Russian Federal Space Agency Roscosmos has erected stations for the GLONASS system in Russia, Antarctica and South Africa, as well as in the Western Hemisphere: it already has four stations in Brazil and since April 2017 it has one in Nicaragua, which due to the secrecy surrounding its function has caused distrust and suspicion in the United States [3] (USA, for its part, has GPS ground stations in its territory and in Australia, Argentina, United Kingdom, Bahrain, Ecuador, South Korea, Tahiti, South Africa and New Zealand).

The Russian Global Navigation Satellite System(Globalnaya Navigatsionnaya Sputnikovaya Sputnikovaya Sistema or GLONASS) is a positioning system operated by the Russian Aerospace Defense Forces. It consists of 28 satellites, allowing real-time positioning and speed data for surface, sea and airborne objects around the world. [ 4] In principle GLONASS does not transmit any identification information staff; in fact, user devices only receive signals from the satellites, without transmitting anything back. However, it was originally developed with military applications in mind and carries encrypted signals that are supposed to provide higher resolutions to authorized military users (same the US GPS). [5]

In Brazil, there are four ground stations used to track signals from the GLONASS constellation. These stations serve as correction points in the western hemisphere and help to significantly improve the accuracy of navigation signals. Russia is in close and transparent partnership with the Brazilian space agency (AEB), promoting the research and development of the South American country's aerospace sector.

|

In 2013, the first station was installed, located at campus of the University of Brasilia, which was also the first Russian station of that subject abroad. Another station followed at the same location in 2014, and later, in 2016, a third one was placed at the high school Federal Science Education and Technology of Pernambuco, in Recife. The Russian Federal Space Agency Roscosmos built its fourth Brazilian station on the territory of the Federal University of Santa Maria, in Rio Grande do Sul. In addition to fulfilling its main purpose of increasing the accuracy and improving the performance of GLONASS, the facility can be used by Brazilian scientists to carry out other types of scientific research . [6]

The level of transparency that surrounded the construction and then prevailed in the management of the stations in Brazil is definitely not the same applied to the one opened in Managua, the capital of Nicaragua. There are several pieces of information that sow doubts regarding the real use of the station. To begin with, there is no information on the cost of the facilities or on the specialization of the staff. The fact that it has been placed a short distance from the U.S. Embassy has given rise to conjecture about its use for eavesdropping and espionage.

In addition, vague answers from representatives of Nicaragua and Roscosmos about the use of the station have failed to convey confidence about project. It is a "strategicproject " for both Nicaragua and Russia, concluded Laureano Ortega, the son of the Nicaraguan president. Both countries claim to have a very fluid and close cooperation in many spheres, such as in projects related to health and development, however none of them have materialized with such speed and dedication. [7]

Given Russia's increased military presence in Nicaragua, empowered by the agreement facilitating the docking of Russian warships in Nicaragua announced by Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu during his visit to the Central American country in February 2015, and also concretized in the donation of 50 Russian T-72B1 tanks in 2016 and the increasing movement of the Russian military staff , it can be concluded that Russia clearly sees strategic importance in its presence in Nicaragua. [ 8] [ 9] All this is viewed with suspicion from the U.S. The head of the U.S. Southern Command, Kirt Tidd, warned in April that "the Russians are pursuing an unsettling posture" in Nicaragua, which "impacts the stability of the region."

Undoubtedly, when world powers such as Russia or the United States act outside their territory, they are always guided by a combination of motivations. Strategic moves are essential in the game of world politics. For this very reason, the financial aid that a country receives or the partnership that it can establish with a great power is often subject to political conditionality. In this case, it is difficult to know for sure what exactly is the goal of the station in Nicaragua or even those in Brazil. At first glance, the goal seems neutral-offering higher quality of navigation system and providing a different option to GPS-but given the new value Russia is placing on its geopolitical capabilities, there is the possibility of a more strategic use.