Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label use .

▲Flags in a welcome ceremony given to the US vice president in Tokyo, in February 2018 [White House].

COMMENTARY / Gabriel de Lange [English version].

Over the last few decades China has grown in economic and political strength. One of the most recent developments was the inclusion of the document Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era in the Communist Party of China's (CPC) Constitution, which took place during the 19th Congress held in Beijing in October 2017. Later on, in March 2018, the National People's Congress approved to remove from the country's Constitution the limit of two presidential terms. These steps have consolidated the power of the current Chinese leader.

The United States of America on the other hand has been criticized on multiple fronts for its dealings in Asia. Some authors say that Trump's approaches to North Korea, China, and other Asian countries "are damaging US interests" in the Asia-Pacific region, specifically in his rash handling of the threat of North Korea. In terms of economics, withdrawing the US from the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) "has undermined America's influence" in shaping the Asia-Pacific's future and "given China an enormous opportunity to shape that future on its own terms." The withdrawal has made many Asian countries concerned with what the United States brings to the table in terms of economic engagement, and this may encourage them to look to China to fill this void.

One of the main factors that keep Asian countries' foreign policy at a distance from China and closer to the US is due to trouble in the South China Sea, such as in the case of the Philippines with the Spratly Islands or Vietnam with the Parcel Islands. Many have noted these countries' concerns about Chinese intentions "have pushed them closer to the United States." Unfortunately for the US, this dependency is more reliant on China's own decision whether or not to insist their claims to particular islands. This is subject to change if the Xi administration decides that the benefits of stronger relations with their neighbors are more important than these disputed territories.

The question now is, who will the other Asian countries, especially those members of ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations) look to rely on as a political ally? With signs of firm, stable, and lasting Chinese power under the authority of Xi Jinping, compared to a seemingly unpredictable, divided, and internationally criticized Trump administration, one may not be surprised to see Asian foreign policies leaning more towards China in the near future.

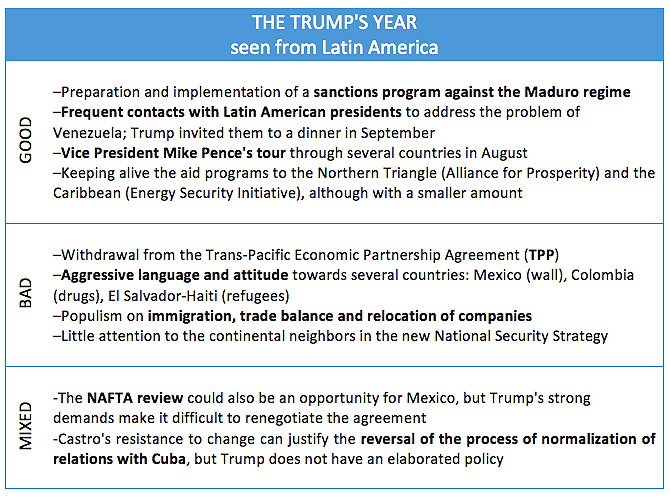

The neighbors of the United States in the Western Hemisphere find it difficult to interpret the first year of the new administration

Donald Trump reaches his first anniversary as president of the United States having caused some recent fires in Latin America. His rude disregard for El Salvador and Haiti, due to the high figures of refugees sheltered in the U.S., and his harsh treatment of Colombia, for the increase in cocaine production, had damaged relations. Although they were already complicated in the case of Mexico, throughout the year they had some good times, such as the presidents' dinner that Trump summoned in September in New York in which a united action was drawn on Venezuela.

▲Trump in his first 100 days as president [White House].

ARTICLE / Garhem O. Padilla [English version] [Spanish version].

One year after the inauguration of the 45th President of the United States of America, Donald John Trump (the ceremony was on January 20), the controversy dominates the balance of the new administration, both in his domestic as well as international performance. The continental neighbors of the United States, in particular, show bewilderment about Trump's policies towards the hemisphere. On the one hand, they regret the American disinterest in commitments of economic development and multilateral integration; on the other hand, they note some activity in relation to some regional problems, such as the Venezuelan one. The actual balance is mixed, although there is unanimity that the language and many of Trump's forms threaten relationships.

From the TPP to NAFTA

In the economic field, the Trump era started with the definitive withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement (TPP), on January 23, 2017. This made it impossible to enter into force since the United States is the market through which above all, this agreement emerged. The U.S. withdrawal affected the perspectives of the Latin American countries participating in the initiative.

Then, the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), demanded by Trump, was opened. The doubts about the future of the NAFTA, signed in 1994 and that Trump has described as "disaster", have stood out in what is going of the administration. Some of its demands, which Mexico and Canada oppose, are to increase the share of products manufactured in the United States, and the "sunset" clause, which would force the treaty to be reviewed methodically every five years and suspend it if any of its three members did not agree. All this, arises from the idea of the U.S. president to suspend the treaty if it is not favorable for his country.

Cuba and Venezuela

If the quarrels with Mexico have not yet reached to an end, in the case of Cuba, Trump has already retaliated against the Castro regime, with the expulsion in October of 15 Cuban diplomats from the Cuban Embassy in Washington in response to"the sonic attacks" that affected 24 U.S. diplomats on the island. The White House, in addition, has revoked some conciliatory measures of the Obama administration because the Castro regime is not responding with open-ended concessions.

As far as Venezuela is concerned, Trump has made strong efforts in terms of introducing measures and sanctions against corrupt officials, in addition to addressing the political situation with other countries, so that they support those efforts aimed at eradicating the Venezuelan crisis, thus generating multilateralism between American countries. However, this policy has detractors, who believe that the sanctions are not intended to achieve a long-term objective, and it is not clear how they would promote Venezuelan stability.

Although in those actions on Cuba and Venezuela Trump has alluded to the democratic principles violated by the governors of Havana and Caracas, his administration has not insisted especially on the commitment to human rights, democracy and moral values, as being usual in the argumentation of the U.S. foreign policy. Some critics point out that the Trump administration is willing to promote human rights only when they meet its political objectives.

This could explain the worsening of the opinion that exists in Latin America about the United States and about the relations with that country. According to the Latinobarómetro survey 2017, the favorable opinion has fallen to 67%, seven points below that at the end of the Obama administration, which was 74%. This survey shows a significant difference for Mexico, one of the countries that, without a doubt, has the worst levels of favorable opinion towards the Trump administration: in 2017 it was 48%, which means a fall of 29 points in comparison with 2016, in which it was 77%.

|

Immigration, withdrawal, decline

The restrictive immigration policies applied would also explain that rejection of the Trump administration by Latin American public opinion. In the immigration section the most recent is the decision not to renew the authorization to stay in the United States of thousands of Salvadorans and Haitians, who once entered the U.S. fleeing calamities in their countries.

We must also allude to Trump's efforts to achieve one of its main objectives since the beginning of his political campaign: to build a border wall with Mexico. The U.S. president has not had much success at this time, since although he has looked for ways to finance it, what he has managed to introduce in the budgets is very insignificant in relation to the estimated costs.

Trump's protectionism entails a withdrawal that may be accentuating the decline of the U.S. leadership in Latin America, especially against other powers. China has been increasing its economic and political performance in countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Peru and Venezuela. Russia, for its part, has strengthened diplomatic and security relations with Cuba. It could be said that, taking advantage of the conflicts between Cuba and the United States, Moscow has tried to keep the island in its orbit through a series of investments.

Threats to security

This leads us to mention the new National Security Strategy of the United States, announced in December. The document presented by Trump addresses the rivalry with China and Russia, and also refers to the challenge posed by the regimes of Cuba and Venezuela, by the supposed threats to security they represent and the support of Russia they receive. Trump expressed great desire to see Cuba and Venezuela join "shared freedom and prosperity" and called for "isolating governments that refuse to act as responsible partners in advancing hemispheric peace and prosperity."

Similarly, the new U.S. Security Strategy refers to other challenges in the region, such as transnational criminal organizations, which impede the stability of Central American countries, especially Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. All in all, the document only dedicates one page to Latin America, in line with Washington's traditional attention given to the areas of the world that most affect their interests and security.

An opportunity for the United States to approach the Latin American countries will be the Summit of the Americas, which will be held next March in Lima. However, nothing is predictable given the characteristic attitude of the president, which leaves a large open space for possible surprises.

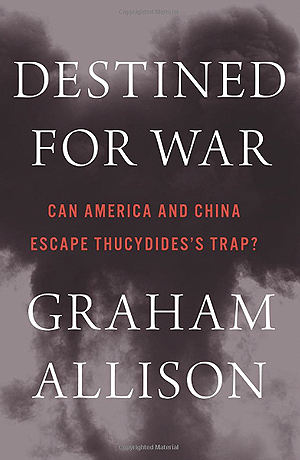

[Graham Allison, Destined for War. Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap? Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Boston, 2017. 364 pages]

REVIEW / Emili J. Blasco [Spanish version]

This is what has been called the Thucydides Trap: the dilemma facing a hegemonic power and a rising one that threatens that hegemony. Is war inevitable? When Thucydides recounted the Peloponnesian War, he wrote about the inevitability for the dominant Sparta and the emerging Athens to think of armed confrontation as a means of settling the conflict.

The fact that these two Greek polis necessarily thought about war –and finally they waged it–, does not mean that they did not have other options. History has shown that there are other alternatives: when Wilhemine Germany threatened to overcome Britain's naval force, the attempt of sorpasso (accompanied by several circumstances) led to the First World War, but when Portugal was overtaken by Spain in overseas possessions in the sixteenth century, or when the United States replaced Britain as the world's leading power in the late nineteenth century the power transfer was peaceful.

Destined for War. Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap?, by Graham Allison, is a call to Washington and Beijing to do everything possible to avoid falling into the trap described by the Greek historian. In this book, the founding dean of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government reviews several historical precedents. Harvard's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, of which Allison is director, has researched on them in a program called precisely Thucydides's Trap.

This concept is defined by Allison as "the severe structural stress caused when a rising power threatens to upend a ruling one. In such condition, not just extraordinary, unexpected events, but even ordinary flashpoints of foreign affairs, can trigger large-scale conflict."

|

The structural stress is produced by the clash of two deep sensibilities: the rising power syndrome ("a rising state's enhanced sense of itself, its interests, and its entitlement to recognition and respect"), and its mirror image, the ruling power syndrome ("the established power exhibiting an enlarged sense of fear and insecurity as it faces intimations of decline").

Along with those syndroms, the two rival powers also experience a 'secutity dilemma': "A rising power may discount a ruling state's fear and insecurity because it 'knows' itself to be well-meaning. Meanwhile, its opponent misunderstands even positive initiatives as overly demanding, or even threatening."

The use of military force

Allison starts from the fact that China is already putting itself on par with the United States as a world power. It has done so in terms of the volume of its economy (China has already overtaken the U.S. in Purchasing Power Parity) and with regard to some aspects of military force (a report by Rand Corporation predicted that in 2017 China would have an "advantage" or "approximate parity" in 6 of the 9 areas of conventional capability). The author's assumption is that China will soon be able to wrest from the United States the scepter of main superpower. In this situation, how will both countries react?

In the case of China, its thousand-year perspective will probably lead to an attitude of patience, provided there is at least some small progress in its purpose of increasing its global weight. Since 1949 China has only resorted to force in three of 33 territorial disputes. In those cases, the Chinese leaders waged the war –they were limited wars, conceived as a warning to their opponents– even though the enemy was equal or greater, urged by a situation of domestic unrest.

For Allison, "As long as developments in the South China Sea are generally moving in China's favor, it appears unlikely to use military force. But if trends in the correlation of forces should shift against it, particularly at a moment of domestic political instability, China would initiate a limited military conflict, even against a larger, more powerful state like the US."

For its part, the United States can choose several strategies, according to Allison: accommodate to the new reality, undermine Chinese power (commercial war, fostering separatism of the provinces), negotiate a long peace, and redefine the relationship. The author does not give firm advice, but seems to suggest that Washington should move between the last two options.

He recalls how Britain understood that it could not compete with the United States in the Western Hemisphere, and how from there a collaboration between the two countries grew, as manifested in the First and Second World War. This should happen by accepting that the South China Sea is an area of Chinese influence. The United States should admit this, not out of mere condescension, but because it proceeds to a real clarification of its vital interests.

Despite its positive tone, Destined for War is one of the essays by the American establishment where the end of the American era and the passing the baton to China are most openly announced (it does not seem to glimpse a multipolar or bipolar world, but rather a primacy of the Asian country). It is also one of those assays that puts less accent –clearly less than it should– on the remaining strengths of the U.S. and the problems that can undermine the coronation of China.