Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label william walker .

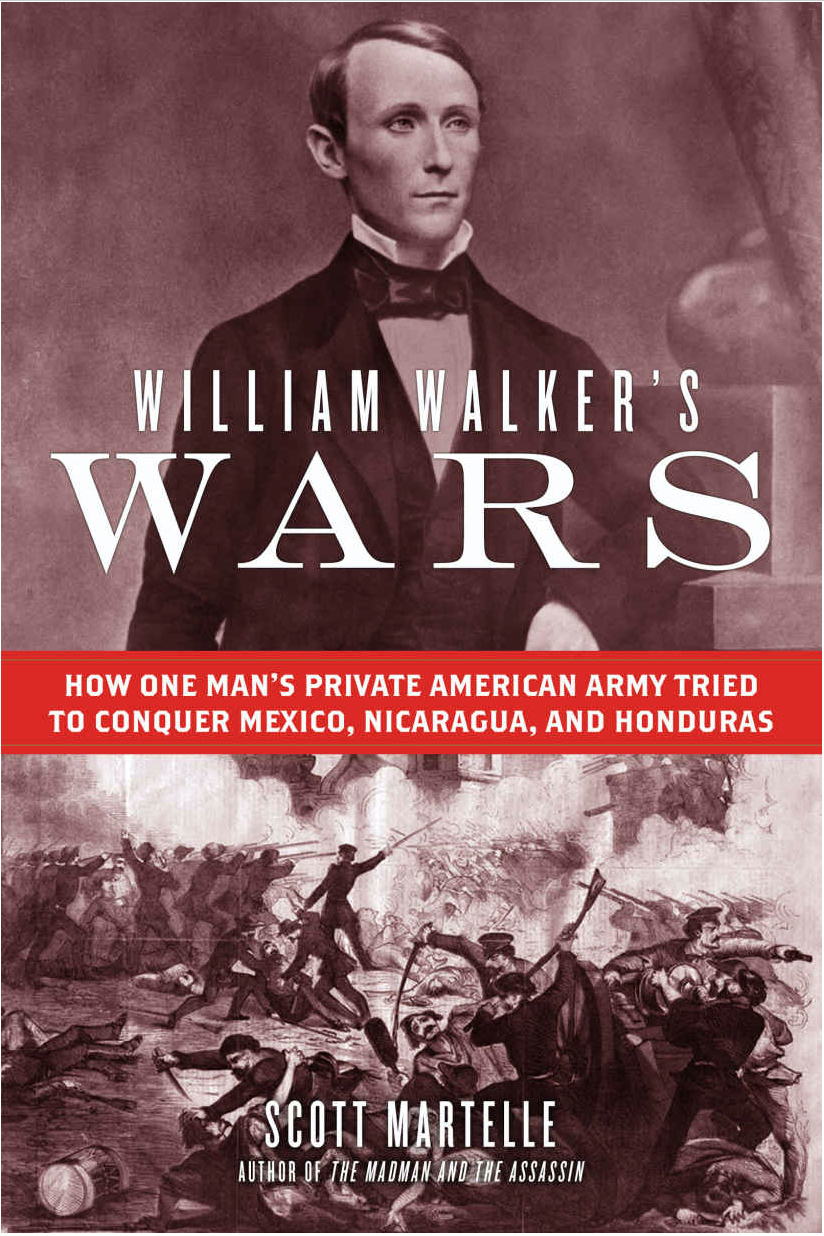

[Scott Martelle, William Walker's Wars. How One Man's Private Army Tried to Conquer Mexico, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Chicago Review Press. Chicago, 2019. 312 p.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

The history of US interference in Latin America is long. In plenary session of the Executive Council Manifest Destiny of westward expansion in the mid-19th century, to extend the country from coast to coast, there were also attempts to extend sovereignty to the South. Those who occupied the White House were satisfied with half of Mexico, which completed a comfortable access to the Pacific, but there were personal initiatives to attempt to purchase and even conquer Central American territories.

The history of US interference in Latin America is long. In plenary session of the Executive Council Manifest Destiny of westward expansion in the mid-19th century, to extend the country from coast to coast, there were also attempts to extend sovereignty to the South. Those who occupied the White House were satisfied with half of Mexico, which completed a comfortable access to the Pacific, but there were personal initiatives to attempt to purchase and even conquer Central American territories.

One such initiative was led by William Walker, who, at the head of several hundred filibusters - the American Phalanx - seized the presidency of Nicaragua and dreamed of a slave empire that would attract investment from American Southerners if slavery was abolished in the United States. Walker, from Tennessee, first tried to create a republic in Sonora, to integrate that Mexican territory into the US, and then focused his interest on Nicaragua, then an attractive passage for Americans who wanted to cross the Central American isthmus to the gold mines of California, where he himself had sought his fortune. Disallowed and detained several times by the US authorities, due to the problems he caused them with neighbouring governments, he was finally expelled from Nicaragua by force of arms and shot dead while trying to return by setting foot in Honduras.

Scott Martelle's book is both a portrait of the character - someone with no special leadership skills and a rather delicate appearance unbefitting a mercenary chief, who nevertheless managed to generate lucrative expectations among those who followed him (2,518 Americans enlisted) - and a chronicle of his military campaigns in the South of the United States. It also describes well the mid-19th century atmosphere in cities such as San Francisco and New Orleans, filled with migrants from other parts of the country and in transit to wherever fortune would take them.

It also provides a detailed account of the business developed by the tycoon Vanderbilt to establish a route, inaugurated in 1851, which used the San Juan River to reach Lake Nicaragua and from there to the Pacific, with the aim of establishing a railway connection and the subsequent purpose to build a canal in a few years. Although the overland route was longer than the one that at that time was also being made under similar conditions on the Isthmus of Panama, the journey by boat from the USA to Nicaragua was shorter than the one that required going all the way to Panama. The latter explains why, during the second half of the 19th century, the project Nicaragua Canal had more supporters in Washington than the Panama Canal.

While Panama is one of the symbols of US interference in its "backyard", the success of the transoceanic canal project and its return to the Panamanians largely defuses a "black legend" that still exists in the Nicaraguan case. Nicaragua is probably the Central American country that has experienced the most US "imperialism". The Walker episode (1855-1857) marks a beginning, followed by the US government's own military interventions (1912-1933), Washington's close support for the Somoza dictatorship (1937-1979) and direct involvement in the fight against the Sandinista Revolution (1981-1990).

Walker arrived in Nicaragua, attracted by US interest in the inter-oceanic passage and with the excuse of helping one of the sides in one of the many civil wars between conservatives and liberals in the former Spanish colonies. Elevated to head of the army, in 1856 he was elected president of a country in which he could barely control the area whose centre was the city of Granada, on the northern shore of Lake Nicaragua.

As he established his power he moved away from any initial idea of integrating Nicaragua into the US and dreamed of forging a Central American empire that would even include Mexico and Cuba. Slavery, which had been abolished in Nicaragua in 1838 and reinstated by him in 1856, entered into his strategy. He envisioned it as a means of preventing Washington from giving up extending its sovereignty to those territories, given the internal balances in the US between slave and non-slave states, and as an attraction of capital from southern slaveholders. He was finally expelled from the country in 1857 thanks to the push of an army assembled by neighbouring countries. In 1860 he attempted a return, but was captured and shot in Trujillo (Honduras). His adventure was fuelled by a belief in the superiority of the white, Anglo-Saxon man, which led him to despise the aspirations of the Hispanic peoples and to overestimate the military capacity of their mercenaries.

Martelle's book responds more to a historicist than a popularising purpose , so it is not so much for the general public as for those specifically interested in William Walker's Fulibusterism: an episode, in any case, of convenient knowledge on the Central American past and the relationship of the United States with the rest of the Western Hemisphere.