Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label refugees .

Disputed ethnicity, British colonial-era grievances and fear of a 'fifth columnist' minority

The humanitarian crisis suffered in Myanmar by the Muslim minority Rohingyas also raises strategic issues. With the country surrounded by Islamic populations, certain ruling groups, especially Buddhist elements, fear that the Rohingyas, who are declared foreigners despite having been on their territory for generations, will act as fifth columnists. Fear of jihadist contamination is also invoked by a government that has not respected the human rights of this minority.

▲ Rohingya refugees [Tasnim News Agency/CC].

article / Alexia Cosmello Guisande

In August 2017, what was known as "the great exodus of the Rohingyas" took place in Myanmar; a year later, in 2018, the humanitarian catastrophe taking place in that country reappeared on the front pages of international newspapers. The international community, automatically, came out in favor of the Rohingya minority group . The media talked about the problem, and continue to do so, using populist language, trying to seek the emotion of the public.

The Rohingya story is little known to the public, who are generally unaware of the origin of the conflict and the Burmese government's motives. Currently, the Rohingyas are considered by the UN as "one of the most persecuted minorities in the world". In order to understand the core of the current problem, it is of great importance to make a brief analysis of the history of Myanmar, of the Rohingyas and of the relations between this minority and the country that hosts them.

History

The current state of Myanmar is a real mosaic of ethnicities, languages, religions and insurgent movements. There are 135 different ethnic groups recognized, but approximately 90% of the population is of Buddhist religion, so that the remaining denominations are considered as minorities in the country [1]. Specifically, the Rohingyas are of Muslim religion and more than half of the community is concentrated in the Rakhine or Arakan region, one of the poorest in the country. Here the population is roughly divided between: 59.7% Buddhists, 35.6% Muslims and the remaining 4.7% other religions.

The Muslims of Rakhine are divided into two groups, on the one hand, the Kaman, who despite being of another confession, share customs with the Buddhist population and are recognized and guaranteed citizenship in Myanmar by the Government. On the other hand, the Rohingyas, who are a mixture of different ethnic groups such as Arabs, Mughals and Bengalis. This second group, group , has no recognized nationality or citizenship in the State, since, despite the fact that its members have been in the country for generations, they are still considered illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

It was between 1974, when the Emergency Immigration Law was issued, and 1982, when the Citizenship Law was passed during the dictatorial period of General Ne Win, that the Rohingyas were declared by law illegal immigrants without the right to citizenship in Myanmar. This law, together with the Government's refusal to separate them into identities, is one of the reasons why the conflict between the authorities and the Rohingyas began. To the conflict must be added the involvement of the military, which tends to instigate confrontation in the region between different ethnic groups.

Because they are stateless, which is in itself a violation of human rights, they lack recognition of other basic rights such as access to work, Education or health care, as well as freedom of movement within their own country. The conflict with this minority community goes beyond religion, as it also affects the political-economic aspects of group. They are being culturally discriminated against, economically exploited and politically marginalized.

Arguments

|

Rakhine region on the coast of Myanmar, adjacent to Bangladesh. |

To understand the Myanmar government's arguments for denying them citizenship, one must understand the history of the community. In itself, their origin is unclear, which makes their status more complex and controversial. They themselves claim to be indigenous people originally from the region they now inhabit, Rakhine. History does not contradict this, but neither does it confirm it; there is historical evidence that they have been living there for generations. On the one hand, a version of their origin, collected by historian Jasmine Chia, dates the first Muslim settlements in Arakan (former name of Rakhine) during the seventh century; these settlers continued to live in the region until the ninth century, but it was not until the fifteenth century when they settled definitively and formed a community. Versions of local historians contradict the previous version and date the first Rohingya settlements in the nineteenth century when the place was under the colonization of the British Empire, along with India and Bangladesh, so they argue that they were actually settled in Chittagong and with the transit of people and internal exodus migrated to Rakhine. Finally, French historian Jacques P. Leider states that the first time the term "Rohingya" was used was by a British doctor in the 18th century, so even though they were not yet settled in the area at that time, the ethnic group already existed.

The Second World War is considered to be the origin of the current problem. Japan wanted to invade Burma, so the British Empire decided to arm the Rohingyas to fight against the Japanese. But the group used the weapons given by the authorities, as well as the techniques learned, to defend the country against them. They burned lands and temples of other ethnic groups, mainly Buddhists. In 1944 they pushed the Japanese back, for which the British, who were still in control of the area, praised them [2].

In 1948 Burma gained independence from the British Empire, which gave several minorities representing 40% of today's Myanmar the opportunity to arm themselves and rebel against the new political system. Even today parts of the country are still controlled by these groups. Prior to independence, the country's Muslims formed the Muslim Liberation Organization (MLO), which after 1948 was renamed the Mujahid Party. This group is on the Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium (TRAC) list of terrorist groups. The Government allowed the removal from the country's terrorist list of those groups that had signed a ceasefire with the State. This implies that the Government allows their free development and investment in these areas in need after years of isolation. In other words, these groups can now move freely around the country and participate in politics. This is not the case of the Rohingyas, who are still considered a group of foreigners and a vehicle for the expansion of jihad, from agreement with the point of view of the Myanmar Government and the Buddhists. In the recent period, the Islamic State has been expanding the Islamic religion narrative internationally, for this reason Buddhist monks (Ashin Wirathu) have called Islam a religion that directly threatens the Myanmar state and warn that it is through the Muslim minority that such violent ideas can more easily permeate the country due to the contact of elements of that minority with international terrorist groups.

The Burmese government justifies its actions against the Rohingyas on the grounds that the conflict between the two religions since the period of British colonization may lead to further conflicts. On the other hand, there is fear on the part of the Government, Buddhists and other minorities towards the Rohingyas because of their organizations such as the Arakan Rohingha National Organization or the Rohingya Solidarity Organization, which have an almost direct connection with leaders and/or members of terrorist groups such as Al-Qaeda or the Taliban.

Buddhists view with concern the rapid population growth of Muslims, which will possibly lead in the not too distant future to Muslims being in a position to outnumber the Buddhist community at issue , thus ceasing to be a minority. Linked to this fear is the fact that the country is surrounded by nations of Muslim religion, and according to Buddhists, if there were an unexpected invasion of Myanmar by some of these countries, the Rohingyas would fight in favor of the invaders, as they do not feel part of the country [3].

Resentment

While this fear on the part of Buddhists and the government itself is understandable, the human rights violations, some of which have led to real humanitarian crises, are not justifiable. In fact, behind the anti-Rohingya attitude, beyond the arguments officially invoked before the international community, there seems to be a historical resentment towards this minority for the burning of temples and land during the colonial era and a fear of open confrontation.

Clearly, a country's history marks its present and its future, and those events of decades ago explain part of what is happening in Myanmar today. While past grievances cannot be forgotten, dragging the desire for revenge from generation to generation is the best recipe for failure as a society or even tragedy. The abused Rohingya children are growing up hating the country in which they reside, which is counterproductive to the government's objectives and feeds back into the fear of one to the reaction of the other.

[1] FARZANA, Kazi Fahmida. Memories of Burmese Rohingya Refugees: Contested Identity and Belonging. "Introduction" (p. 1-40).

[2] ROGERS, Benedict. Burma: A Nation at the Crossroads. Rider Books, 2015

[3] FARZANA, K. F. op. cit. "The Refugee Problem from an Official Account" (p. 59-86).

essay / Lucía Serrano Royo

Currently, some 60 million people are forcibly displaced in the world (Arenas-Hidalgo, 2017). [1] The figures become more significant if it is observed that more than 80% of migratory flows are directed to developing countries development, while only 20% have as goal developed countries, which in turn have more means and wealth, and would be more suitable to receive these migratory flows.

In 2015, Europe welcomed 1.2 million people, which was an unprecedented magnitude since the Second World War. This status has led to an intense discussion on solidarity and responsibility among Member States.

The way in which this subject has been legislated in the European Union has given rise to irregularities in its application among the different States. This subject within the European Union system is a shared skill of the area of freedom, security and justice. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) in its article 2.2 and 3 establishes that in these competences, it is the States that must legislate insofar as the Union does not exercise its skill. This has given rise to a partial development and inequalities.

development legislative

The figure of refugees is reflected for the first time in an international document in the Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951) and its 1967 protocol . (UNHCR: The UN Refugee Agency, 2017)[2]. Despite this breakthrough, the treatment of refugees was different in each Member State, as their national policy was dealt with. Therefore, in an attempt to harmonize national policies, the Dublin agreement was signed in 1990. However, it was not until the Treaty of Amsterdam in May 1999, when it was established as goal to create an area of freedom, security and justice, treating the subject immigration and asylum as a shared skill . Already in October 1999, the European committee held a special session for the creation of an area of freedom, security and justice in the European Union, concluding with the need to create a Common European Asylum System (CEAS) (CIDOB, 2017)[3]. Finally, these policies in subject of asylum become subject common with the Lisbon Treaty and its development in the TFEU.

Currently, its raison d'être is set out in Article 67 et seq. of the TFEU, which states that the Union shall constitute an area of freedom, security and justice with respect for fundamental rights and the different legal systems and traditions of the Member States. This area shall also guarantee the absence of controls on persons at internal borders. Furthermore, it is established that the EU will develop a common policy on asylum, immigration and external border control (art 67.2 TFEU) based on solidarity between Member States, which is fair towards third-country nationals. But the area of freedom, security and justice is not a watertight compartment in the treaties, but has to be interpreted in the light of other sections.

This skill should be analyzed, on the one hand, under the framework of free movement of persons within the European Union, and on the other hand, taking into account the financial field. As regards the free movement of persons, article 77 TFEU must be applied, which calls on the Union to develop a policy ensuring the total absence of checks on persons at internal borders, while guaranteeing checks at external borders. To this end, the European Parliament and the committee, in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure , must establish a common policy on visas and other short-stay permits residency program , controls and conditions under which third-country nationals may move freely within the Union. As regards the financial sphere, account must be taken of article 80 TFEU, which establishes the principle of solidarity in asylum, immigration and control policies, taking into account the fair sharing of responsibility among Member States.

Furthermore, a fundamental aspect for the development of this subject has been the harmonization of the term refugee by the Union, defining it as third-country nationals or stateless persons who are outside their home country and are unwilling or unable to return to it due to a well-founded fear of being persecuted on account of their race, religion, nationality or opinion (Eur-ex.europa.eu, 2017)[4]. This is of particular importance because these are the characteristics necessary to acquire refugee status, which in turn is necessary to obtain asylum in the European Union.

status in Europe

Despite the legislative development , the response in Europe to the humanitarian crisis following the outbreak of the Syrian conflict, together with the upsurge of conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Eritrea or Somalia, has been very ineffective, which has shaken the system.

The decision to grant or withdraw refugee status belongs to each State's internal authorities and may therefore differ from one State to another. What the European Union does is to guarantee common protection and ensure that asylum seekers have access to fair and efficient asylum procedures. This is why the EU is trying to establish a coherent system for decision making in this regard by the Member States, developing rules on the whole process of application asylum. In addition, in the event that the person does not meet the requirements criteria for refugee status, but is in a status sensitive situation due to risk of serious harm in case of return to his or her country, he or she is entitled to subsidiary protection. The principle of non-refoulement applies to these persons, i.e. they have the right first and foremost not to be taken to a country where there is a risk to their lives.

The problem with this system is that Turkey and Lebanon alone host 10 times more refugees than the whole of Europe, which up to 2016 only processed 813,599 asylum applications. Specifically, Spain granted protection to 6,855 applicants, of which 6,215 were Syrians[5]; despite the increase compared to previous years, the figures were still the lowest in the European environment.

Many of the people who disembark in Greece or Italy, set off again towards the Balkans through Yugoslavia and Serbia to Hungary, in view of the deficiencies of management and the precarious conditions they found in these host countries.

In an attempt to implement the principle of solidarity and cooperation, a series of quotas were established in 2015 to alleviate the humanitarian crisis and the pressure established in Greece and Italy. Member states were to share 120,000 asylum seekers, and all countries were to abide by it. The main stakeholder was Germany. Another mechanism that was set up was a fund with position to the Refugee Mechanism in Turkey, to meet the needs of refugees hosted in that country. The Commission allocated a total amount of €2.2 billion, and budgeted €3 billion in 2016-2017[6].

Faced with this status countries have reacted differently within the Union. In contrast to countries such as Germany, which is looking for a way to combat aging and population reduction in its state through the entrance of refugees, other Member States are reluctant to implement the policies. Even in some EU countries, nationalist parties are gaining strength and support: in the Netherlands, Geert Wilders (Freedom Party); in France, Marine Le Pen (National Front); and in Germany, Frauke Petry (Alternative for Germany party). Although these parties are not the main political force in these countries, this reflects the dissatisfaction of part of the population with the entrance of refugees in the States. The case of the United Kingdom is also noteworthy, since one of the causes of Brexit was the desire to regain control over the entrance of immigrants in the country. In addition, the United Kingdom initially opted out of the quota system applied in the other Member States. As confirmed in her negotiations, Prime Minister Theresa May prioritizes the rejection of immigration over free trade in the EU.

Specific mechanisms for development of the ESLJ

The borders between the different countries of the Union have become blurred. With the Schengen border code and the Community code on visas, borders have been opened and integrated, thus allowing the free movement of people. The operation of these systems has required the establishment of common rules on the entrance of persons and the control of visas, since once the external border of the EU has been crossed, controls are minimal. Therefore, documentation checks vary depending on the places of origin of the recipients, with a more detailed control for non-EU citizens. Only exceptionally is there provision for the reintroduction of internal border controls (for a maximum period of thirty days), in the event of a serious threat to public order and internal security.

Since the control of external borders depends on the States where they are located, systems such as Frontex 2004 have been created, from the ad hoc Border Control Centers established in 1999, which provides financial aid to the States in the control of the external borders of the EU, mainly to those countries that suffer great migratory pressures (Frontex.europa.eu, 2017) [7]. The Internal Security Fund, a financial support system emerged in 2014 and aimed at strengthening external borders and visas, has also been created.

Another active mechanism is the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), to strengthen the cooperation of EU countries, where theoretically Member States should allocate 20% of the available resources[8]. For its implementation, the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) (2014-2020) was established necessary for promote the effectiveness of the management of migration flows. In addition, an asylum policy for the European Union has been established in the CEAS, which includes a directive on asylum procedures and a directive on reception conditions. The Dublin Regulation, from agreement with the Geneva Convention, is integrated into this system. It is a fundamental mechanism and although this system has been simplified, unified and clarified, it has caused more controversy at subject of refugees. It was established to streamline asylum application processes in the 32 countries that apply the Regulation. Under this law, only one country is manager of the examination of its application: the country that takes the refugee's fingerprints, i.e., the first one he or she arrived in and applied for international protection. This works regardless of whether the person travels to or seeks asylum in another country; the competent country is the one in which the refugee was first fingerprinted. This system relies on EURODAC, as it is a central system that financial aid EU Member States to determine the country manager to examine an asylum application by comparing fingerprints.

The committee European Refugees and Exiles has highlighted the two main problems of this system: on the one hand, it leads refugees to travel clandestinely and dangerously until they reach their destination country, in order to avoid being fingerprinted by a country other than the one in which they want to settle. On the other hand, Greece and Italy, which are the main destinations of migrant flows, cannot cope with the burden this system imposes on them to process the masses of people arriving on their territory in search of protection.

Cases before the EU Court of Justice

The Court of Justice of the European Union has ruled on various aspects relating to immigration and the treatment of refugees by the Member States. On some occasions the Court has remained steadfast in the application of the homogeneous rules and regulations of the Union, while in other cases the Court has left the matter to the discretion of the different Member States.

The court ruled in favor of a joint action in the case of a third country national (Mr. El Dridi) who illegally entered Italy without permission from residency program. On May 8, 2004 the Prefect of Turin issued against him a decree of expulsion. The CJEU (CJEU, 28 April 2011)[9] ruled that despite the fact that an immigrant is in status illegally and remains in the territory of the referred Member State without just cause, even with the concurrence of an infringement of an order to leave the said territory in a given deadline , the State cannot impose a prison sentence, since following Directive 2008/115, they exclude the criminal skill of the Member States in the field of illegal immigration and irregular status . Thus, the States must adjust their legislation to ensure compliance with EU law.

On the other hand, the court leaves it up to the States to decide to send back to a third country an immigrant who has applied for international protection on its territory, if it considers that this country meets the criteria of a "safe third country". Even the court ruled (CJEU, December 10, 2013) [10]that, in order to streamline the processing of asylum applications and to avoid obstruction of the system, the Member State retains its prerogative in exercising the right to grant asylum regardless of which Member State manager of the examination of a application. This School leaves a large margin of appreciation to the States. Homogeneity in this case can only be seen in the case of systematic shortcomings of the asylum procedure and of the conditions of reception of asylum seekers in that State, or degrading treatment.

For a more active attitude

The European Union has established a multitude of mechanisms, and has skill to set them in motion, but its passivity and the reluctant attitude of the Member States in welcoming refugees call into question the unity of the European Union system and the freedom of movement that characterizes the EU itself. The status it faces is complex, as there is a humanitarian crisis arising from the flow of migrants in need of financial aid at its borders. Meanwhile, States are passive and even against improving the system, to the point that some States have proposed the restoration of internal border controls (El Español, 2017).[11] This status has been caused mainly by a lack of effective control over their borders within the Union, and on the other hand by a society that sample wary of open borders because of insecurity.

The refugee crisis is a real problem and closing the borders will not make the problem go away. This is why European countries should adopt a common and active perspective. The earmarking of funds serves as financial aid in this humanitarian crisis, but it is not the only solution. One of the main unresolved problems is the status of people in refugee camps, who are in precarious conditions and should be received in a dignified manner. The Union should react more actively to these situations, making use of its skill in subject of asylum and immigration arrivals with massive influx, as stated in art 78 TFEU c).

This status remains one of the main objectives for the diary of the European Union since the White Paper establishes the reinforcement of the diary Migration, actions on the refugee crisis and aspects on the population crisis in Europe. It advocates for an increase in immigration policies and protection of legal immigration, while combating illegal immigration, helping both immigrants and the European population (European Commission, 2014) [12]. Despite these positive plans and perspectives, it is necessary to take into account the delicate status that the EU is facing internally, with cases such as the withdrawal of a State with power within the Union (the Brexit), which could lead to a diversion in the efforts of community policies, leaving aside crucial issues, such as the status of refugees.

[1] Arenas-Hidalgo, N. (2017). Massive population flows and security. The refugee crisis in the Mediterranean. [online] Redalyc.org [Accessed 9 Jul. 2017].

[2] UNHCR: The UN Refugee Agency (2017) Who is a Refugee? [online] [Accessed 10 Jul. 2017]

[3] CIDOB. (2017). CIDOB - Refugee policy in the European Union. [online] [Accessed 10 Jul. 2017].

[4] Eur-lex.europa.eu. (2017). EUR-Lex - l33176 - EN - EUR-Lex. [online] Available [Accessed 10 Jul. 2017].

[5] data of CEAR (Comison Española de financial aid al Refugiado) of March 2017 Anon, (2017). [online] [Accessed 10 May 2017].

[6] Anon, (2017). [online] [Accessed 11 Jul. 2017].

[7] Frontex.europa.eu (2017). Frontex | Origin. [online] [Accessed 12 Jul. 2017].

[8] https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/e-library/docs/ceas-fact-sheets/ceas_factsheet_es.pdf [Accessed 12 Jul. 2017].

[9] Court of Justice of the European Union [online]. ECLI:EU:C:2011:268, dated 28 April 2011 [accessed 10 June 2017].

[10] Court of Justice of the European Union [online].ECLI:EU:C:2013:813, of10 December 2013 [accessed 10 June 2017].

[11] El Español (2017). European border controls may squander a third of growth. [online] [Accessed 11 Jul. 2017].

[12] European Commission (2014). Migration and asylum.

DOCUMENT FROM work / María Granados Machimbarrena

SUMMARY

Despite the HIRSI and JAMAA judgment of 2012, Italy was condemned in 2015 once again by the European Court of Human Rights for unlawful detention and summary and collective refoulement of several migrants. The events occurred in 2011, when the applicants travelled in a boat across the Mediterranean and were intercepted by Italian vessels. The migrants were transferred to the island of Lampedusa, and detained at the Centro di Soccorso e Prima Accoglienza (CSPA), in a area reserved for Tunisian nationals. According to the complainants, they were detained in overcrowded and filthy rooms, without contact with the outside. The events took place immediately after the Arab Spring. The issues raised before the Court by the applicants and the arguments raised by the judges are relevant in the current context of the European crisis in the management handling of refugee flows by the EU institutions and its Member States.

download the complete document [pdf. 6,4MB] [pdf. 6,4MB

download the complete document [pdf. 6,4MB] [pdf. 6,4MB

Publicador de contenidos

Back to Argentina ve en Vaca Muerta una tabla de salvación, pero falta más capital para su desarrollo

The hydrocarbon field is the centrepiece of President Alberto Fernández's 2020-2023 Gas Plan, which subsidises part of the investment.

Activity of YPF, Argentina's state-owned hydrocarbon company [YPF].

ANALYSIS / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa

Argentina is facing a deep economic crisis that is having a severe impact on the standard of living of its citizens. The country, which had managed to emerge with enormous sacrifices from the corralito of 2001, sees its leaders committing the same macroeconomic recklessness that led the national Economics to collapse. After a hugely disappointing mandate by Mauricio Macri and his economic "gradualism", the new administration of Alberto Fernández has inherited a very delicate status , now aggravated by the global and national crisis generated by Covid-19. Public debt is now almost 100% of GDP, the Argentine peso is worth less than 90 units to the US dollar, while the public deficit persists. The Economics is still in recession, accumulating four years of decline. The IMF, which lent nearly $44 billion to Argentina in 2018 in the largest loan in the institution's history, has begun to lose patience with the lack of structural reforms and hints of debt restructuring by the government. In this critical status , Argentines are looking to the development unconventional oil industry as a possible way out of the economic crisis. In particular, the Vaca Muerta super field has been the focus of attention of international investors, government and citizens for the last decade, being a very promising project not Exempt of environmental and technical challenges.

The energy sector in Argentina: a history of fluctuations

The oil sector in Argentina has more than 100 years of history since oil was discovered in the Patagonian desert in 1907. The geographical difficulties of area - lack of water, distance from Buenos Aires and salty winds of more than 100 km/h - meant that project advanced very slowly until the outbreak of the First World War. The European conflict interrupted coal imports from England, which until then had accounted for 95% of Argentina's energy consumption. business The emergence of oil in the inter-war period as a strategic raw subject commodity revalued the sector, which began to receive huge foreign and domestic investment in the 1920s. By 1921, YPF, the first state-owned oil company in Latin America, was created, with energy self-sufficiency as its main goal goal. The country's political upheaval during the so-called Década Infame (1930-43) and the effects of the Great Depression damaged the incipient oil sector. The years of Perón's government saw a timid take-off of the oil industry with the opening of the sector to foreign companies and the construction of the first oil pipelines. In 1958, Arturo Frondizi became President of Argentina and sanctioned the Hydrocarbons Law of 1958, achieving an impressive development of the sector in only 4 years with an immense policy of public and private investment that multiplied oil production threefold, extended the network of gas pipelines and generalised access to natural gas for industry and households. The oil regime in Argentina kept the ownership of resource in the hands of the state, but allowed the participation of private and foreign companies in the production process.

Since the successful 1960s in subject oil, the sector entered a period of relative stagnation in parallel with Argentina's chaotic politics and Economics at the time. The 1970s was a complex journey in the desert for YPF, mired in huge debt and unable to increase production and secure the longed-for self-sufficiency.

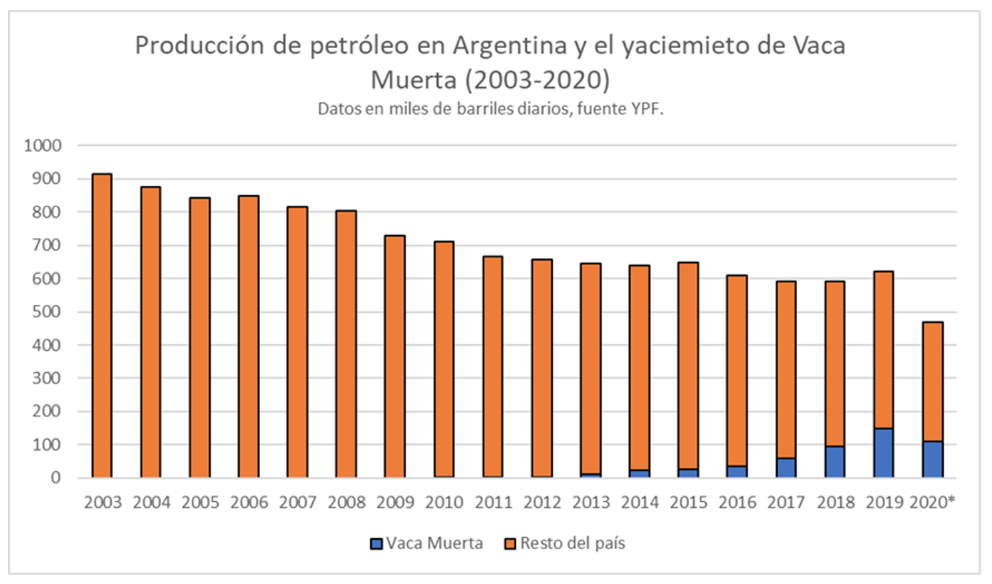

The so-called Washington Consensus and the arrival of Carlos Menem to the presidency in 1990 saw the privatisation of YPF and the fragmentation of the state monopoly over the sector. By 1998, YPF was fully privatised under the ownership of Repsol, which controlled 97.5% of its capital. It was in the period 1996-2003 that peak oil production was reached, exporting natural gas to Chile, Brazil and Uruguay, and exceeding 300,000 barrels of crude oil per day in net exports.

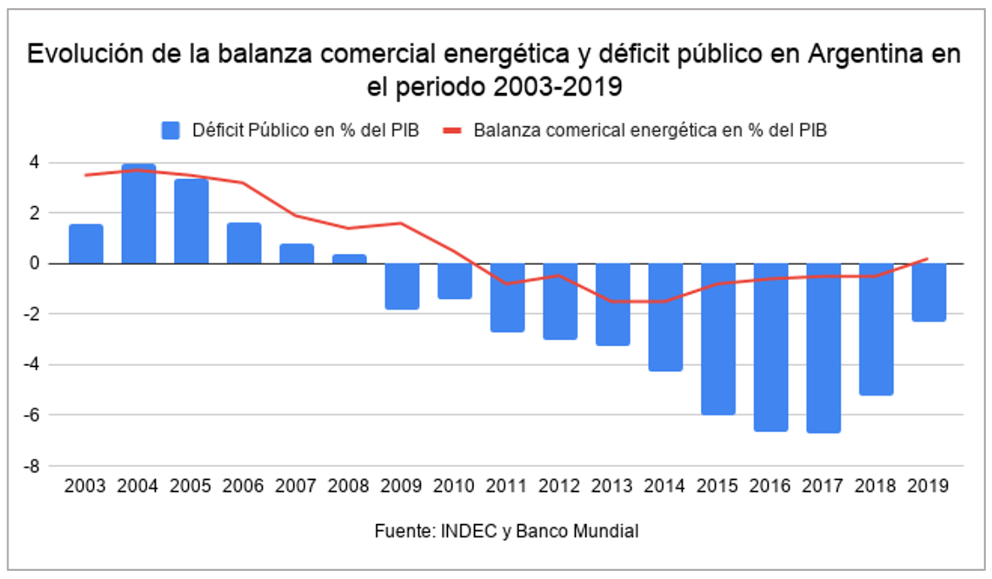

However, a turnaround soon began in the face of state intervention in the market. Domestic consumption with fixed sales prices for oil producers was less attractive than the export market, encouraging private companies to overproduce in order to export oil and increase revenues exponentially. With the rise in oil prices of the so-called "commodity super-cycle" during the first decade of this century, the price differential between exports and domestic sales widened, creating a real incentive to focus on production. Exploration was thus left in the background, as domestic consumption grew rapidly due to tax incentives and a near horizon was foreseen without the possibility of exports and, therefore, lower income from the increase in reserves.

The exit from the 2001 crisis took place in a context of fiscal and trade surpluses, which allowed the country to regain the confidence of international creditors and reduce the volume of public debt. It was precisely the energy sector that was the main driver of this recovery, accounting for more than half of the trade surplus in the period 2004-2006 and one of Argentina's main sources of fiscal revenue. However, as mentioned above, this production was not sustainable due to the existence of a fiscal framework that distorted oil companies' incentives in favour of immediate consumption without investing in exploration. By 2004, a new tariff was applied to crude oil exports that floated on the basis of the international price of crude, reaching 45% if the price was above 45 dollars. The excessively rentier approach of Néstor Kirchner's presidency ended up dilapidating the sector's investment incentives, although it is true that they allowed for a spectacular increase in derived fiscal revenues, boosting Argentina's generous social and debt repayment plans. sample As a good illustration of this decline in exploration, in the 1980s more than 100 exploratory wells were drilled annually, in 1990 the figure exceeded 90, and by 2010 the figure was 26 wells per year. This figure is particularly dramatic if one takes into account the dynamics that the oil and gas sector tends to follow, with large investments in exploration and infrastructure in times of high prices, as was the case between 2001-2014.

In 2011, after a decade of debate on the oil sector in Argentina, President Cristina Fernández decided to expropriate 51 per cent of the shares of YPF held by Repsol, citing reasons of energy sovereignty and the decline of the sector. This decision followed the line taken by Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales in 2006 to increase the state's weight in the hydrocarbons sector at a time of electoral success for the Latin American left. The expropriation took place in the same year that Argentina became a net energy importer and coincided with the finding of the large shale reserves in Neuquén precisely by YPF, now known as Vaca Muerta. YPF at the time was the direct producer of approximately one third of Argentina's total volume. The expropriation took place at the same time as the imposition of the "cepo cambiario", a system of capital controls that made private foreign investment in the sector even less attractive. Not only was the country unable to recover its energy self-sufficiency, but it also entered a period of intense imports that hampered access to dollars and produced a large part of the macroeconomic imbalance of the current economic crisis.

The arrival of Mauricio Macri in 2015 heralded a new phase for the sector with policies more favourable to private initiative. One of the first measures was to establish a fixed price at the "wellhead" of the Vaca Muerta oil fields with the idea of encouraging the start-up of projects. As the economic crisis worsened, the unpopular measure of increasing electricity and fuel prices by more than 30 per cent was chosen, generating enormous discontent in the context of a constant devaluation of the Argentine peso and the rising cost of living. The energy portfolio was marked by enormous instability, with three different ministers who generated enormous legal insecurity by constantly changing the hydrocarbons regulatory framework . Renewable solar and wind energy, boosted by a new energy plan and greater liberalisation of investment, managed to double their energy contribution during Mauricio Macri's time in the Casa Rosada.

Alberto Fernández's first years have been marked by unconditional support for the hydrocarbons sector, with Vaca Muerta being the central axis of his energy policy, announcing the 2020-2023 Gas Plan that will subsidise part of the investment in the sector. On the other hand, despite the context of the health emergency, 39 renewable energy projects were installed in 2020, with an installed capacity of around 1.5 GW, an increase of almost 60% over the previous year. In any case, the continuity of this growth will depend on access to foreign currency in the country, which is essential to be able to buy panels and windmills from abroad. The boom in renewable energy in Argentina led the Danish company Vestas to install the first windmill assembly plant in the country in 2018, which already has several plants producing solar panels to supply domestic demand.

Characteristics of Vaca Muerta

Vaca Muerta is not a field from a technical point of view, it is a sedimentary training of enormous magnitude with dispersed deposits of natural gas and oil that can only be exploited with unconventional techniques: hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. These characteristics make Vaca Muerta a complex activity, which requires attracting as much talent as possible, especially from international players with experience in the exploitation of unconventional hydrocarbons. Likewise, conditions in the province of Neuquén are complex given the scarcity of rainfall and the importance of the fruit and vegetable industry, in direct competition with the water resources required for the exploitation of unconventional oil.

Since finding, the potential of Vaca Muerta has been compared to that of the Eagle Ford basin in the United States, which produces more than one million barrels per day. Evidently, the Neuquén region has neither Texas' oil business ecosystem nor its fiscal facilities, making what might be geologically similar in reality two totally different stories. In December 2020, Vaca Muerte produced 124,000 barrels of oil per day, a figure that is expected to gradually increase over the course of this year to 150,000 barrels per day, about 30% of the 470,000 barrels per day Argentina produced in 2020. Natural gas follows a slower process, pending the development of infrastructure that will allow the transport of large volumes of gas to consumption and export centres. In this regard, Fernández announced in November 2020 the Plan for the Promotion of Argentine Gas Production 2020-2023, with which the Casa Rosada seeks to save dollars by substituting imports. The plan facilitates the acquisition of dollars for investors and improves the maximum selling price of natural gas by almost 50%, to 3.70 dollars per mbtu, in the hope of receiving the necessary investment, estimated at 6.5 billion dollars, to achieve gas self-sufficiency. Argentina already has the capacity to export natural gas to Chile, Uruguay and Brazil through pipelines. Unfortunately, the floating vessel exporting natural gas from Vaca Muerte left Argentina at the end of 2020 after YPF unilaterally broke the ten-year contract with the vessel's owner, Exmar, citing economic difficulties, limiting the capacity to sell natural gas outside the continent.

One of the great advantages of Vaca Muerta is the presence of international companies with experience in the aforementioned US unconventional oil basins. The post-2014 learning curve of the US fracking sector is being applied in Vaca Muerta, which has seen drilling costs fall by 50% since 2014 while gaining in productivity. The influx of US capital may accelerate if Joe Biden's administration fiscally and environmentally restricts oil activities in the country, from agreement with its environmentalist diary . Currently the main operator in Vaca Muerta after YPF is Chevron, followed by Tecpetrol, Wintershell, Shell, Total and Pluspetrol, in an ecosystem with 18 oil companies working in different blocks.

Vaca Muerta as a national strategy

It is clear that achieving energy self-sufficiency will help Argentina's macroeconomic problems, the main headache for its citizens in recent years. No Exempt of environmental risk, Vaca Muerta could be a lifeline for a country whose international credibility is at an all-time low. Alberto Fernández's pro-hydrocarbon narrative follows the line of his Mexican counterpart Andrés guide López Obrador, with whom he intends to lead a new moderate left-wing axis in Latin America. The spectre of the nationalisation of YPF by the now vice-president Cristina Fernández, as well as the recent breach of contract with Exmar, continue to generate uncertainty among international investors. status Moreover, the poor financial performance of YPF, the main player in Vaca Muerta, with a debt of more than 8 billion dollars, is a major drag on the country's oil prospects. Similarly, Vaca Muerta is far from realising its potential, with significant but insufficient production to guarantee revenues that would bring about a radical change in Argentina's economic and social status . In order to guarantee its success, a context of favourable oil prices and the fluid arrival of foreign investors are needed. Two variables that cannot be taken for granted given Argentina's political context and the increasingly strong decarbonisation policy of traditional oil companies.

The big question now is how to reconcile the large-scale fossil fuel development with Argentina's latest commitments on climate change subject : to reduce CO2 emissions by 19% by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Similarly, the promising trajectory of renewable energy development during Mauricio Macri's presidency may lose momentum if the oil and gas sector attracts public and private investment, crowding out solar and wind.

Vaca Muerta is likely to advance slowly but surely as international oil prices stabilise upwards. The possibility of generating foreign currency and boosting a Economics on the verge of collapse should not be underestimated, but expecting Vaca Muerta to solve Argentina's problems on its own can only end in a new episode of frustration in the southern country.