Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label budget European .

The always difficult negotiations are made more difficult by the 75 billion euros the UK is giving up.

ANALYSIS / Pablo Gurbindo Palomo

The negotiations for the European budget for the period 2021-2027 are crucial for the future of the Union. After the failure of the extraordinary summit on 20-21 February, time is running out and the member states must put aside their differences in order to reach an agreement on agreement before 31 December 2020.

framework The negotiation of a new European Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) is always complicated and crucial, as the ambition of the Union depends on the amount of money that member states are willing to contribute. But the negotiation of this new budget line, for the period 2021-2027, has an added complication: it is the first without the United Kingdom after Brexit. This complication does not lie in the absence of the British in the negotiations (for some that is more of a relief) but in the 75 billion euros they have stopped contributing.

What is the MFP?

framework The Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF ) is the EU's long-term budgetary framework deadline and sets the limits for expense of the Union, both as a whole and in its different areas of activity, for a deadline period of no less than 5 years. In addition, the MFF includes a number of provisions and "special instruments" beyond that, so that even in unforeseen circumstances such as crises or emergencies, funds can be used to address the problem. This is why the MFF is crucial, as it sets the political priorities and objectives for the coming years.

This framework is initially proposed by the Commission and, on this basis, the committee (composed of all Member States) negotiates and has to come to a unanimous agreement . After this the proposal is sent to the European Parliament for approval.

The amount that goes to the MFF is calculated from the Gross National Income (GNI) of the Member States, i.e. the sum of the remuneration of the factors of production of all members. But customs duties, agricultural and sugar levies and other revenues such as VAT are also part of it.

Alliances for war

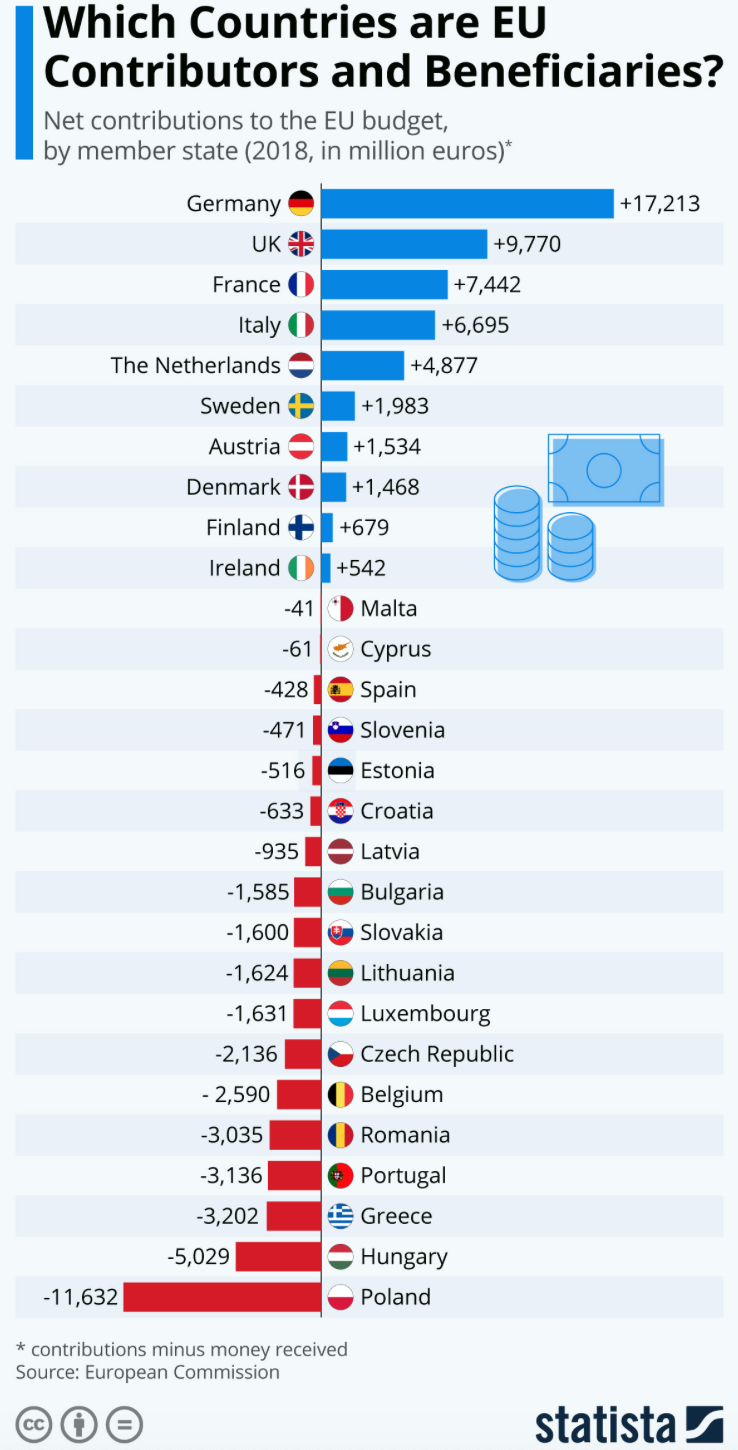

In the EU there are countries that are "net contributors" and others that are "net receivers". Some pay more to the Union than they receive in return, while others receive more than they contribute. This is why countries' positions are flawed when they face these negotiations: some want to pay less money and others do not want to receive less.

Like any self-respecting European war, alliances and coalitions have been formed beforehand.

The Commission 's proposal for the MFF 2021-2027 on 2 May 2018 already made many European capitals nervous. The proposal was 1.11 % of GNI (already excluding the UK). It envisaged budget increases for border control, defence, migration, internal and external security, cooperation with development and research, among other areas. On the other hand, cuts were foreseen in Cohesion Policy (aid to help the most disadvantaged regions of the Union) and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

The Parliament submitted a report provisional on this proposal in which it called for an increase to 1.3% of GNI (corresponding to a 16.7% increase from the previous proposal ). In addition, MEPs called, among other things, for cohesion and agriculture funding to be maintained as in the previous budget framework .

On 2 February 2019 the Finnish Presidency of committee proposed a negotiation framework starting at 1.07% of GNI.

This succession of events led to the emergence of two antagonistic blocs: the frugal club and the friends of cohesion.

The frugal club consists of four northern European countries: Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Austria. These countries are all net contributors and advocate a budget of no more than 1 % of GNI. On the other hand, they call for cuts to be made in what they consider to be "outdated" areas such as cohesion funds or the CAP, and want to increase the budget in other areas such as research and development, defence and the fight against immigration or climate change.

Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz has already announced that he will veto on committee any proposal that exceeds 1 % of GNI.

The Friends of Cohesion comprise fifteen countries from the south and east of the Union: Spain, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. All these countries are net recipients and demand that CAP and cohesion policy funding be maintained, and that the EU's budget be based on between 1.16 and 1.3 % of GNI.

This large group met on 1 February in the Portuguese town of Beja. There they tried to show an image of unity ahead of the first days of the MFP's discussion , which would take place in Brussels on the 20th and 21st of the same month. They also announced that they would block any subject cuts.

It will be curious to see whether, as the negotiations progress, the blocs will remain strong or whether each country will pull in its own direction.

Outside of these two groups, the two big net contributors stand out, pulling the strings of what happens in the EU: Germany and France.

Germany is closer to the frugals in wanting a more austere budget and more money for more modern items such as digitalisation or the fight against climate change. But first and foremost it wants a quick agreement .

France, for its part, is closer to the friends of cohesion in wanting to maintain a strong CAP, but also wants a stronger expense in defence.

The problem of "rebates

And if all these variables were not enough, we have to add the figure of the compensatory cheques or "rebates. These are discounts to a country's contribution to budget. This figure was created in 1984 for the United Kingdom, during the presidency of the conservative Margaret Thatcher. For the "Iron Lady", the amount that her country contributed to budget was excessive, as most of the amount (70%) went to the CAP and the Cohesion Funds, from which the UK hardly benefited. It was therefore agreed that the UK would have certain discounts on its budgetary contribution on a permanent and full basis.

And if all these variables were not enough, we have to add the figure of the compensatory cheques or "rebates. These are discounts to a country's contribution to budget. This figure was created in 1984 for the United Kingdom, during the presidency of the conservative Margaret Thatcher. For the "Iron Lady", the amount that her country contributed to budget was excessive, as most of the amount (70%) went to the CAP and the Cohesion Funds, from which the UK hardly benefited. It was therefore agreed that the UK would have certain discounts on its budgetary contribution on a permanent and full basis.

These compensatory cheques have since been given to other net contributor countries, but these had to be negotiated with each MFF and were partial on a specific area such as VAT or contributions. An unsuccessful attempt was already made to eliminate this in 2005.

For the frugal and Germany these cheques should be kept, on civil service examination to the friends of cohesion and especially France, who want them to disappear.

Sánchez seeks his first victory in Brussels

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is staking much of his credibility in both Europe and Spain on these negotiations.

In Europe, for many he failed in the negotiations for the new Commission. Sánchez started from a position of strength as the leader of Europe's fourth Economics after the UK's exit. He was also the strongest member of the Socialist group parliamentary , which has been in the doldrums in recent years at the European level, but was the second strongest force in the European Parliament elections. For many, therefore, the election of the Spaniard Josep Borrell as High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, with no other socialist in key positions, was seen as a failure.

Sánchez has the opportunity in the negotiations to show himself as a strong and reliable leader so that the Franco-German axis can count on Spain to carry out the important changes that the Union has to make in the coming years.

On the other hand, in Spain, Sánchez has the countryside up in arms over the prospects of reducing the CAP. And much of his credibility is at stake after his victory in last year's elections and the training of the "progressive coalition" with the support of Podemos and the independentistas. The Spanish government has already taken a stand with farmers, and cannot afford a defeat.

Spanish farmers are highly dependent on the CAP. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food: "in 2017, a total of 775,000 recipients received 6,678 million euros through this channel. In the period 2021-2027 we are gambling more than 44,000 million euros."

There are two different types of CAP support:

-

Direct aids: some are granted per volume of production, per crop (so called "coupled"), and the others, the "decoupled" ones, are granted per hectare, not per production or yield and have been criticised by some sectors.

-

Indirect support: this does not go directly to the farmer, but is used for the development of rural areas.

The amount of aid received varies depending on the sector, but can amount to up to 30 % of a farmer's income. Without this aid, a large part of the Spanish countryside and that of other European countries cannot compete with products coming from outside the Union.

Failure of the first budget summit

On 20 and 21 February an extraordinary summit of the European committee took place in order to reach a agreement. It did not start well with the proposal of the president of the committee, Charles Michel, for a budget based on 1.074% of GNI. This proposal convinced nobody, neither the frugal as excessive, nor the friends of cohesion as insufficient.

Michel's proposal included the added complication of linking the submission of aid to compliance with the rule of law. This measure put the so-called Visegrad group (Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia) on guard, as the rule of law in some of these countries is being called into question from the west of the Union. So, another group is taking centre stage.

The Commission's technical services made several proposals to try to make everyone happy. The final one was 1.069% of GNI. Closer to 1%, and including an increase in rebates for Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Austria and Denmark, to please the frugal and attract the Germans. But also an increase in the CAP to please the friends of cohesion and France, at the cost of reducing other budget items such as funding for research, defence and foreign affairs.

But the blocs did not budge. The frugal ones remain entrenched at 1%, and the friends of cohesion in response have decided to do the same, but at the 1.3% proposed by the European Parliament (even if they know it is unrealistic).

In the absence of agreement Michel dissolved the meeting; it is expected that talks will take place in the coming weeks and another summit will be convened.

Conclusion

The EU has a problem: its ambition is not matched by the commitment of its member states. The Union needs to reinvent itself and be more ambitious, say its members, but when it comes down to it, few are truly willing to contribute and deliver what is needed.

The Von der Leyen Commission arrived with three star plans: the European Green Pact to make Europe the first carbon-neutral continent; digitalisation; and, under Josep Borrell, greater international involvement on the part of the Union. However, as soon as the budget negotiations began and it became clear that this would lead to an increase in the expense, each country pulled in its own direction, and it was these subject proposals that were the first to fall victim to cuts due to the impossibility of reaching an understanding.

A agreement has to be reached by 31 December 2020, if there is to be no money at all: neither for CAP, nor for rebates, nor even for Erasmus.

Member States need to understand that for the EU to be more ambitious they themselves need to be more ambitious and willing to be more involved, with the increase in budget that this entails.