Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs World order, diplomacy and governance .

[Josep Piqué. The world that is coming to us. Challenges, Challenges and Expectations of the 21st Century: A Post-Western World with Western Values? Deusto. Barcelona, 2018. 254 pp.]

review / Ignacio Yárnoz

|

Europe may lose relative economic weight or, worse, demographic weight and competitiveness, putting the sustainability of its welfare state at risk. It may become less and less relevant on the global geopolitical stage and move away from the planet's new center of gravity. However, it remains an indisputable pole of attraction for the rest of humanity due to its peace, democracy, freedom, gender equality and opportunities, tolerance and respect. This is what the author Josep Piqué wants to convey to us in The World That Comes to Us. We are talking about an economist, businessman and political leader – head of several ministries, including Foreign Affairs, during the government of José María Aznar – who has experienced first-hand the transition from a Eurocentric world to one that looks more to a thriving Asia.

The work turns out to be a good geopolitical analysis of the world, in which a fragmented European Union, a very thriving China, a Russia nostalgic for its imperial past, a Middle East divided in wars between irreconcilable factions and an Anglo-Saxon world withdrawn into itself stand out. I divide it into different chapters depending on the area geographically, the book takes an in-depth look at each and every topic.

First of all, the author emphasizes the status that the Anglo-Saxon world is experiencing, especially the United States and the United Kingdom, countries that have renounced their world hegemony for the sake of a retreat into themselves. In the case of the United Kingdom, we talk about the divorce from the European Union, and in the case of the United States, we talk about President Donald Trump's policies, such as the withdrawal of the TPP (Trans Pacific Partnership) with Japan, Chile, Canada, Australia, Brunei, New Zealand, Mexico, Peru, Malaysia, Vietnam and Singapore. Paradoxically, in the face of the attitude of these two actors, there is the rise as a power of a China that no longer dissembles in its actions, that no longer wants to be that silent power that Deng Xiaoping formulated.

Russia and its actions abroad are also subject to analysis from different perspectives, but mainly in light of Russia's obsession with its security. As the author argues, it is a state that is very sensitive to its borders and tries to keep the enemy poles as far apart as possible, which implies a policy of influence in the states bordering its border. This explains their reactions to the change of sides of the Eastern European countries and their gradual incorporation into the European Union or NATO. Nor can we forget the topic of gas, the implications of the melting of the Arctic, the oil deposits in the Caspian Sea or other issues that the author reviews.

If we look at the picture in the Middle East, the status It does not seem to be reaching a lasting peace. Neither in the panorama of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, nor in the different proxy wars between Iran and Saudi Arabia, not to mention the failure of the different Arab Springs. This status It leads the author to analyze in historical perspective how all this has happened. On the other hand, it analyzes the complexity of the different intersecting interests between Turkey, Syria, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Iran that complete the chessboard represented by the Middle East.

Finally, we must not forget the chapter that Josep Piqué reservation for your thesis at the beginning of this article. article: the future of the European Union. As he himself points out, Europe represents the neo-Western synthesis in a post-Western world. However, you need to realize this potential and benefit from it. As Piqué argues, the attractiveness of the European Union as much as project inclusive as well as the liberal and democratic values it represents must be a card that the EU must play more in its favour. However, it also faces challenges such as the rise of nationalism and anti-Europeanism, Russian interference in internal affairs and the lack of credibility of the European institutions. All of this in the framework of the severe economic recession of 2007, which the author also analyzes as a good economist of degree program. Finally, we must not forget some final notes dedicated to the implications of new technologies, Latin America and the opportunities that Spain has.

All of this together represents a complete journey through the world of geostrategy – in the review of the regions of the planet, only one is missing. accredited specialization to Africa – which details all the keys that a person with an interest in international relations should take into account when analysing current affairs.

skill of the two powers to have instructions in the Indian Ocean and to be active in strategic neighboring countries.

Rumors of possible future Chinese military use of area in Gwadar (Pakistan), where Beijing already operates a port, have added a great deal of attention in the last year to the rivalry between China and India to secure access to points in the region that will allow them to control the Indian Ocean. India regards this ocean as its own, while for China it is vital to ensure the security of its energy supplies from the Middle East.

▲ China's work to transform Subi Reef in the Spratly Islands into an island in 2015 [US Navy].

article / Jimena Puga

The two major Asia-Pacific powers, China and India, are vying for regional supremacy in the Indian Ocean by establishing military instructions and economic agreements with bordering countries such as Pakistan. The Indian Ocean, which borders Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Australia, is home to one of the most crucial and strategic points for international trade. Nearly 40% of the oil extracted from the sea is produced in the Indian Ocean, which also has rich mineral and fishing deposits.

Five years ago China began its major territorial reclamation in the South China Sea, and the country has established a territorial status quo in its favor without receiving any international impediments, in order to counter the US military presence in the region, established during the Cold War, and which controls the South China Sea and all goods coming from Africa, the Middle East and the Strait of Malacca. This territorial expansion of the Middle Empire began in December 2013; since then China has built more than average dozen more artificial islands, located in a strategic location through which a third of global maritime trade passes, and has deployed military assets on them.

However, the creation of these islands has caused great damage to the region's marine ecosystem. The coral reefs that China has destroyed in order to use them as a base for the establishment of its islands provided food and shelter for numerous marine species, as well as supplies for Asia's most important fishing companies. However, thanks to this territorial expansion China is in a better position not only for maritime and air control of the area but also to continue to advance its strategy of power projection in the Indian Ocean and part of the Pacific to satisfy its plans for power and supremacy in the region.

Neocolonization

In early 2018, some reports suggested that China plans to set up a naval base next to the port it is developing in Gwadar, in Pakistan, although Pakistani authorities deny that Beijing has requested that the facilities be put to that use. In any case, the docking of military vessels at area in Gwadar would connect that point with the country's recent military and naval base built in Djibouti - the first China has abroad - as part of a growing network own of instructions air and naval along the Indian Ocean.

India, the greatest power among regional countries, is responding to Chinese expansion with unexpected strength. Delhi aspires to control the most strategic maritime trade points in the Indian Ocean including the Straits of Malacca and Hormuz and the Mozambique Channel. In addition, India is gaining access to the instructions of its foreign allies in the region. In 2017 it signed a logisticsagreement with the US that would mean free access to US military installations across the region (agreement which perhaps has something to do with the US desire to create an alternative to the Silk Belt and Road Initiative and curb the rapid growth of the Asian superpower).

In January 2018, India also announced the agreement logistical exchange with France involving free access to French military facilities in Djibouti, namely in the Red Sea and on the island of meeting, south of the Indian Ocean (perhaps to counter Sino-European agreements). Finally, India is also building strategic relations and infrastructure near the Persian Gulf. And after years of negotiations, Delhi has managed to formalize a agreement with Iran to modernize and expand the port of Chabahar, near the Strait of Hormuz. While it is true that the vast majority of agreements are commercial in nature, they have enough potential to increase India's access and influence in Central Asia.

In response to Beijing's military base in Djibouti, New Delhi has begun seeking access to new facilities in Seychelles, Oman and Singapore. From Tanzania to Sri Lanka the two Asian powers are attempting to increase their military and economic presence in countries along the Indian Ocean in their mission statement for regional supremacy. Finally, it is possible that India's 2017 request for drones from the US was aimed at goal monitoring Chinese activity in the ocean.

"My Chinese colleagues have explicitly told me that if the U.S. continues to fly over and navigate in what they self-described as 'their waters,' China will shoot down the corresponding intruder," said Matthew Kroenig, a CIA and Pentagon analyst. "Maybe it's just a bluff, but if China were to shoot down an American plane, it would be the perfect scenario for a U.S. military buildup. It's hard to see President Trump or any other American leader turn his back on this issue."

|

PEARL NECKLACE OF CHINA. 1-Hong Kong; 2-Hainan; 3-Paracel Islands (disputed); 4-Spratly Islands (disputed), 5- Sihanoukville and Raum (Cambodia), ports; 6-Itsmo de Kra (Thailand), infrastructure; 7-Cocos Islands (Myanmar), antennas; 8-Sittwe (Myanmar), port; 9-Chittagong (Bangladesh), port; 10-Hambantota (Sri Lanka), port; 11-Marao (Maldives), offshore exploration; 12-Gwadar (Pakistan), port; 13-Port Sudan; 14-Al Ahdab (Iraq), oil exploitation; 15-Lamu (Kenya), port. Chart from 2012; missing to note China's first overseas military base, in Djibouti, inaugurated in 2017 [Edgar Fabiano]. |

Globalization

The moves by both powers stem from the fear that the other countries will join in coalition with their opponent in the future, but they also do not want to completely abandon the expansion of economic relations with each other by altering the regional order too drastically.

This power of the weak has limitations, but it has so far worked to the benefit of both India and China. Due to globalization, particularly in the economic sphere, weaker states have adopted asymmetric strategies to extract resources from their neighboring superpowers that aspire to be leaders on the international stage. Often, these border countries had to choose a superpower to obtain resources, as was the case during the Cold War. The difference in this era of globalization is that these states can extract concessions and resources from both Beijing and Delhi without formally aligning themselves with one of them, as is the case, for example, with Vietnam. The absence of a bloc rivalry, as was the case during the Cold War, and the high levels of economic interdependence between India and China make it easier for many of the smaller states to avoid signing an alliance with one of these leaders.

India's subtle strategy involves developing entente with Japan and the member countries of the association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as well as with the United States. Specifically, the quadrilateral negotiations initiated between India, Japan, the US and Australia are another stabilizing mechanism vis-à-vis China.

However, the strategies of the smaller states in South Asia have limitations. Although China is offering greater economic attendance , these countries, except Pakistan, are unlikely to form military alliances with China because if they do, it would provoke a negative response from India, the dominant power in the region, and the United States, the international superpower that still has a strong naval presence in the Indian Ocean. We are witnessing a new dynamic of diplomatic relations in the Asia-Pacific region.

This new trend of rapprochement with smaller countries translates into an inclination to use economic appeal to persuade neighbors rather than military coercion. How long this trend will continue remains to be seen. India's new strategies with other international powers may be the key to complicating the freedom of action and decision that China is having in the military realm, especially in this time of peace. What is clear is that China's aspiration for supremacy is visible by all countries that are part of the Asia-Pacific region and will not be as easy to establish as the Empire at the Center thought.

[Robert Kagan, The Jungle Grows Back. America and Our Imperiled World. Alfred A. Knoff. New York, 2018. 179 p.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

|

At this point in the century, it is already clear that the consecration of the liberal system in the world, after the breakup of the communist bloc at the end of the Cold War, is not something that will happen inexorably, as was thought. It's not even likely. The divergent models of China and Russia are gaining traction. Democracy is in retreat, even in Western societies themselves.

It is the jungle that grows again where a garden had been extended. This is the image that Robert Kagan uses in his new book to warn about the desirability of the United States not shirking its responsibility to lead the effort to preserve the liberal world order. For Kagan, the liberal system "was never a natural phenomenon," but a "great historical aberration." "It has been an anomaly in the history of human existence. The liberal world order is fragile and not permanent. Like a garden, it is always besieged by the natural forces of history, the jungle, whose vines and weeds constantly threaten to cover it," he says. It is an "artificial creation subject to the forces of geopolitical inertia," so that the question "is not what will bring down the liberal order, but what can sustain it."

Kagan is outlived in the media by the label He is a neoconservative, although his positions are in the central current of American Republicanism (majority for decades, until the rise of Donald Trump; in fact, in the 2016 campaign Kagan supported Hillary Clinton) and his work is developed at the rather Democratic Brookings Institution. He does defend clear U.S. leadership in the world, but not out of self-assertion, but as the only way for the liberal international order to be preserved. It is not that, by sponsoring it, the United States has acted disinterestedly, because as one of its builders, Secretary of State Dean Acheson, said, in order to protect the "American experiment in life" it was necessary to create "an environment of freedom" in the world. But the other Western countries, and others where the regime of freedoms of democratic societies has also been extended, have also benefited.

The thesis Kagan's central point is that, although there was America's own interest in creating the international architecture that ordered the world after World War II, it benefited many other countries and guaranteed the victory of free societies over communism. Crucial to this, according to Kagan, is that while Washington at times acted against the values it preached, it generally played by certain rules.

Thus, the U.S. "did not exploit the system it dominated to gain lasting economic advantages at the expense of the other powers of order. Put simply: he could not use his military dominance to win the economic competition against other members of the order, nor could he treat the competition as zero-sum and insist on always winning. It's true that the U.S. benefited from being the main player both economically and militarily, "but an element of core topic to hold the international order together was the perception of the other powers that they had reasonable opportunities to succeed economically and even sometimes surpass the United States, as Japan, Germany, and other nations did at various times."

Kagan admits that Washington's willingness to engage in large doses of fairplay on the economic plane "did not extend to all areas, particularly not to strategic issues." In these, "order was not always based on rules, because when the United States deemed it necessary, rightly or wrongly, it violated the rules, including those it claimed to defend, either by carrying out military interventions without UN authorization, as it did on numerous occasions during the Cold War, or by engaging in covert activities that had no international backing."

It has been an order that, in order to function, "had to enjoy a certain Degree of voluntary acceptance by its members, not to be a competition of all against all, but a community of like-minded nations acting together to preserve a system from which all could benefit." "Order was kept in place because the other members viewed U.S. hegemony as relatively benign and superior to other alternatives." test This is why the countries of Western Europe trusted Washington despite its overwhelming military superiority. "In the end, even if it didn't always do so for idealistic reasons, the United States would end up creating a world unusually conducive to the spread of democracy."

Kagan disagrees with the view that after the dissolution of the USSR, the planet entered a "new world order." In his view, what was called the "unipolar moment" did not actually change the assumptions of the order established at the end of World War II. That is why it made no sense that, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the world was thought to be entering a new era of unstoppable peace and prosperity, and that this made America's role as a gardener unnecessary. The withdrawal from the world carried out by Trump and initiated by Obama (Kagan already in 2012 published The World America Made, in defense of American involvement in the world), would be allowing the return of the chaotic vegetation of the jungle.

The Jungle Grows Back is in the format of a small book, typical of a essay It is a restrained film that aspires to convey some fundamental ideas without wanting to overwhelm the reader. Despite pointing out the dangers of the liberal order, and noting that the United States is in retreat, the book offers an optimistic message: "This is a pessimistic view of human existence, but it is not a fatalistic view. Nothing is determined, neither the triumph of liberalism nor its defeat."

The text attempts to avoid stagnation, but does not open the door to decisive transformation

Cubans will vote in referendum next February 24 on the project of the new Constitution C by the National Assembly in December after a period of enquiry popular. In the preamble of the project the reference letter was introduced at the last minute to the goal communist which already existed in the 1976 Constitution, but which had not been initially incorporated in the draft, so that the final text is even less novel.

▲ Building of the committee Central of the Communist Party of Cuba [framework Zanferrari].

article / Alex Puigrefagut

Six decades after the Revolution, Cuba leaves behind the surname Castro, with the arrival in April 2018 of Miguel Díaz-Canel as head of state, and is preparing to approve a new Constitution, which will replace the one promulgated in 1976, to symbolize this new time. This new Magna Carta, whose initial text was C by the National Assembly in July 2018, then submitted to three months of popular enquiry for the presentation of amendments and finally C as by the deputies on December 22, has as its goal main objective to seek the modernization of the Cuban State and the sustainable development of the same, without losing the essence and the main ideals of the socialist ideology of the State.

entrance At the end of the Castro era at the helm of Cuba, the State has found it necessary to include in the new essay the socioeconomic transformations carried out in the country since the previous Constitution came into force, as well as to partially modify the State structure to make it more functional. It is also worth mentioning the willingness to recognize more rights for citizens, although with limitations.

When examining the constitutional project , four aspects are particularly noteworthy: the specification of the ideology of the State, the figures and Structures of the State and the government, the question of private property and finally the redefinition of citizens' rights.

Maintenance of socialism

The text C initially by the National Assembly did not include the reference letter at goal to reach a communist society, a fundamental point that was present in the previous Constitution. The article 5 of the 1976 Magna Carta established that society "organizes and orients common efforts towards the high goals of the construction of socialism and the advance towards a communist society".

The omission of this point was really only a change of language, since at no time was the idea of socialism abandoned, in fact, the socialist character of the Cuban State was ratified. In the words of Esteban Lazo, president of the National Assembly, this new Constitution "does not mean that we are renouncing our ideas, but rather that in our vision we are thinking of a socialist, sovereign, independent, prosperous and sustainable country". However, in case there were any doubts, after the period of popular deliberation, the Assembly introduced as an amendment the express accredited specialization to communism in the preamble of the final text, given the alleged pressure from the most immobilist sectors.

The new Constitution reaffirms the socialist character of the Cuban regime, both in the economic and social spheres, giving a leading role to the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) as the highest power in society. The socialist nature of the Cuban State is underscored by the maintenance of the single-party system.

Presidential limits

The new Constitution includes some changes in the state structure. The most outstanding characteristic is that the Antillean country will have a president of the republic as head of state and a prime minister as head of government, in contrast with the current status of the same position for both functions: president of the committee of State and of Ministers. Everything indicates that this distinction will result more in a distribution of work than in a division of powers between the two positions, so this change will not be transcendental, given the control that will continue to be exercised from the PCC.

Another transformation in the political system is the elimination of the provincial assemblies for the creation of provincial governorships, with the goal to give a greater decentralization to the administrative power and a greater dependence of the legislative command on the executive.

As for the presidential term, the new Constitution limits it to five years, with the option of a single reelection for the same period. This change is important since it should lead to a rotation of members, and it is assumed that with this there would also be a renewal of ideas both within the Party and the Executive. The purpose is to avoid the stagnation of a historic generation without new ideas.

Finally, the president will be elected directly by the deputies of the National Assembly; in other words, Cuba does not give entrance to the direct election of its leaders, but maintains the indirect election system.

Private property

The document includes several forms of property, among them socialist property, mixed property and private property. The accredited specialization to the latter does not imply its formal recognition, but the confirmation of a internship whose extension the new Constitution endorses. This implies, therefore, the recognition of the market, a deeper participation of private property and the welcome to more foreign investment to enliven the country's Economics .

This need to reflect in the Constitution the greater participation of private property has occurred because, in many cases, the contribution of property and foreign investments have exceeded in the internship what was established in the previous constitutional framework . But this step will also lead to greater control in this area.

These changes in the economic sphere are aimed at goal to support the adjustments initiated by Raúl Castro a decade ago to boost economic growth and counteract the embargo established by the United States more than fifty years ago; in addition to fixing some of the country's labor force in the private sector as self-employed workers, especially in micro and small enterprises.

Citizen's rights

Finally, regarding the redefinition of citizens' rights, the constitutional project establishes a new functioning in the interaction of the State with the population through the flexibilization of economic, legal and civil rights. From the approval of the new text, the Cuban State must guarantee citizens the extension of Human Rights, although only in accordance with the international treaties ratified by the Caribbean country.

This, which despite this limitation could be seen as an opportunity for citizens, in reality has little of an opening, because although Cuba has signed United Nations agreements on political, cultural, civil and economic rights, it has not actually ratified them. Thus, in principle, Cuba should not be obliged to recognize these rights.

Another highlight of the relaxation introduced is article 40, which criminalizes discrimination "on grounds of sex, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, ethnic origin, skin color, religious belief, disability, national origin or any other distinction harmful to human dignity". In the initial text that went to instructions , the recognition of same-sex marriage was introduced, but citizen rejection led to an amendment that finally withdrew the express protection of same-sex marriage.

After analyzing the main novelties of the constitutional project , it can be determined that the Cuban regime perceives a certain need for change and renewal. The new Constitution goes somewhat in that direction, but although it tries to avoid stagnation, it does not open the door to a decisive transformation either: neither complete continuity -although there is more of this- nor revolution within the system. It is clear that the new generation of leaders, with Miguel Díaz-Canel at the helm, can be seen as a continuity of the Castro regime, for the simple fact that the Castros directly determined the successor, in addition to the fact that many of their ideals are the same as those of the generation that made the revolution. But on the other hand, Cuba is certainly forced to slightly modify its course in order to be more present in the international system and to seek a more functional state and government.

(Updated January 3, 2019)

[Pedro Baños, The World Domain. Elements of power and geopolitical keys. Ariel. Barcelona, 2018. 366 p.]

review / Manuel Lamela

|

If your previous submission, The Keys to World Domination, served as a guide to introduce us to the vast world of geopolitics and international relations, in his new work, Colonel Pedro Baños Bajo, unveils us and gives us a glimpse of the sample the key elements and instruments for world domination and how these are used by the various actors in their constant struggle for power on a global scale. We are on the verge of a paradigm shift on the international scene, and this process, as the author explains, will be led by demography and technology.

In his business In order to democratize geopolitics, Pedro Baños uses clear and precise language to facilitate the understanding of the work. There will be numerous illustrations present in the book that will be accompanied by brief explanations to get a broader vision of the topic to be treated.

The Elements of World Power is the name given to the first half of the book, it is divided into nine different parts that according to the author are key when it comes to understanding the global power game. In this first half, issues of rigorous relevance and tremendously important on the international scene will be discussed. From the hybrid threat, which represents a new way of waging war, to the role of intelligence services today, to the transcendental importance of natural resources and demographics. It is certainly a fairly comprehensive analysis for those looking for a brief explanation of the greatest challenges that threaten to destabilize our current social order. It is true that some of the explanations can be defined as simple, but this does not have to be understood as a pejorative characteristic. The author's ability to synthesize extremely complex issues can encourage the reader's curiosity and make the leap to other great works where they can delve into more specific topics.

In the second part of the book we find a more concrete analysis in which the author focuses on only two factors: technology and demographics. The population imbalance, the large migratory flows and what some call the fourth industrial revolution are some of the issues that Colonel Baños highlights in his analysis. In the author's opinion, the transformations to which these two elements will be exposed will mark the course of humanity in the coming years. In this more incisive study, the author sample how vulnerable human society is to the future changes that are to come and how this alleged weakness will make conflicts difficult to avoid in the near future. Pedro Baños argues that despite the belief we have of living in a perfectly organized and structured society, the reality is far from the latter, since it is a small group The human being charged with directing and leading the destiny of all humanity as a whole.

Despite distilling a certain pessimism throughout the work, Pedro Baños decides to conclude his analysis with a message of hope, advocating for a united humanity. manager and in solidarity with their environment.

The cancellation of the new CDMX airport, already more than 31% built, sows doubts about the economic success of the new administration.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador arrives to the presidency of Mexico facing the economic world, to which he has put up a fight with his advertisement to paralyze the works of the new airport of the capital, despite the fact that a third of the works have already been carried out. The desire to make clear to the economic power who rules the country and to bury what was to be an emblematic bequest of the PRI -whose historical hegemony he hopes to replace with his own party, Morena- may be behind the controversial decision.

▲ Image of the projected NAICM created by Fernando Romero Enterprise, Foster and Partners.

article / Antonio Navalón

The Mexican PRI returned to the presidency of the country in 2012, led by Enrique Peña Nieto, with the promise of making a major investment in public infrastructure that would put Mexico in the world's showcase. The stellar work chosen was the construction of a new airport, whose project was commissioned to architect Norman Foster and which the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) saw as the inheritance that would always be attributed to it.

This great project was to overshadow any negative bequest of Peña Nieto's term, which has been especially marked by corruption cases and historic record violence figures. Although useful for political marketing, increasing the air traffic capacity of Mexico City (CDMX), whose metropolitan area has 23 million inhabitants, is a necessity for boosting the national Economics .

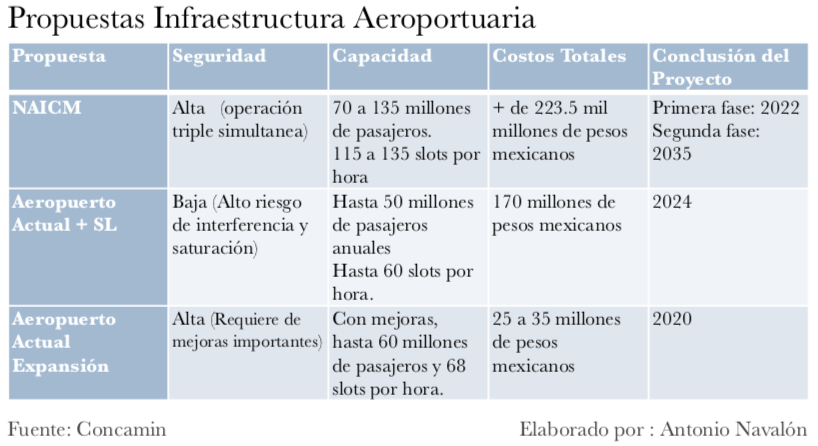

The US$13.3 billion project was one of the largest investments in the country's history. Named Nuevo Aeropuerto Internacional de Ciudad de México (NAICM, later simplified as NAIM) and located at area in Texcoco, a little further away than the current facilities in use, the new infrastructure was to be developed in two phases. The first phase consisted of the construction of a large terminal and three runways, which were initially planned to be ready by 2020, but whose entrance in service had been postponed to 2022 due to construction delays. The second phase would see the construction of three additional runways, plus a second terminal, which would be ready for operation from 2035.

Plans called for NAICM to have the capacity to transport between 70 and 135 million passengers annually, thanks to an operating volume of between 115 and 135 slots per hour. These figures gave a long-term deadline potential benefit of more than $32 billion, according to government estimates.

The project sought first of all to solve the serious air saturation problem suffered by the current Benito Juarez International Airport in Mexico City, caused by the low performance capacity of the two runways that operate simultaneously. In addition, the construction of the NAICM was based on the hope of turning CDMX into a world logistics hub, with the potential to multiply the current airport's cargo transport capacity fourfold.

The level of freight transport in this macro project would be able to reach 2 million tons per year, thus becoming, as its promoters assured, the main distribution center in Latin America. NAICM's ambition, therefore, was to become a reference not only in the American continent but also worldwide, both in the transfer of tourists and in the transport of goods.

NAICM construction began in 2015 and to date 31% of the work has been completed. Although this Degree of completion represents a slight delay compared to the original schedule, the foundation and channeling works are already finished and high Structures intended to hold the wide roof can be seen on the surface. However, despite this progress and the investment already made, the country's new president has announced that he is completely burying the project.

Elections and enquiry

The presidential elections of July 1st were won by the leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador (inaugurated on December 1st). Former leader of the PRI, thanks to which he served as mayor of the capital, over time he drifted to the left: he first joined the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) and, after losing two elections for the presidency of the country, he created the National Regeneration Movement (Morena). In July, Morena won a majority in both chambers of congress and also conquered the CDMX government, giving AMLO, as the new president is commonly known, broad powers to carry out his policies. While he fell 17 votes short of a qualified majority in the Senate that could change the Constitution, he could gain allies for that purpose.

During the election campaign, Lopez Obrador defended the cancellation of the new airport project alleging its high cost, and raised the possibility that, as an alternative, some improvements could be made to the current airport and the Santa Lucia airport, a military base in the area of the Mexican capital that could be enabled for international flights. But Morena's candidate assured that he would make a enquiry to know the opinion of the Mexican people and that he would abide by the results.

Without waiting to take office as President, Lopez Obrador had Morena carry out this enquiry, which was not organized by the Government but by a political party, and furthermore did not take place in the whole country but in 538 municipalities out of the 2,463 that exist in Mexico. The ballot boxes, set up between October 25 and 28, voted "no" to NAICM: with a participation of only 1% of the national electoral body, 69% voted for the alternative of Santa Lucia and 29% voted to continue the works in Texcoco. López Obrador announced that, in application of result, he will halt the works for the new airport, despite the investment already made.

Some popular movements and also naturalists calling for the preservation of the natural environment applauded the advertisement, but there were also protest marches against the decision in the streets of downtown CDMX. The private sector has greatly regretted the purpose decision to cancel the NAICM project . Leading businessmen in the country and organizations such as the Confederation of Mexican Industrial Chambers (CONCAMIN), which represents 35% of Mexican GDP and 40% of employment in the country, came out in defense of the original project and asked López Obrador to reconsider his decision. Their argument is that any alternative will fall short of the demands of growing air traffic, weighing down the country's development . They also argue that any decision other than continuing with the construction of the NAICM will be more expensive than completing the planned airport [1].

|

Economic impact

For CONCAMIN, "the current airport lacks the infrastructure and any improvement would not fix the fundamental problems it has", and a bet on the Santa Lucia base "would be a waste of time and money, which will create problems rather than solve them", according to the president of this business association , Francisco Cervantes.

José Navalón, of CONCAMIN's Foreign Trade and International Affairs Commission, of which he is a member, warns that López Obrador's decision will be a major blow to Mexico's macroeconomic and financial system. In his words, "it is still too early to assess possible consequences, but it will be necessary to see if Mexico has the appropriate airport infrastructure, in terms of competitiveness and connectivity, for what is the second largest Economics in Latin America". In any case, for the moment "there has been a problem of lack of confidence in the markets, which has been immediately reflected in the fall of the peso and the markets" [2].

Indeed, while López Obrador was greeted in July with a rise in the markets, because his resounding victory seemed to augur stability for Mexico, his inauguration in December is being accompanied by an "exodus" of investors. The peso has fallen nearly 10% against the dollar in August, the stock market is down 7.6% and in October alone investors sold 2.4 billion dollars in Mexican bonds.

"The main questions that investors are asking today," Navalón continues, "is whether it is safe to invest in Mexico and how often this subject of decisions that do not follow any subject of legality will be taken," as important companies will be affected by the cancellation of a project in progress. He also warns that "the election of Bolsonaro in Brazil, whose profile is a magnet for foreign investment, may directly affect investment in Mexico".

The big question is why López Obrador maintains his decision against the new airport, in spite of the economic penalty it will mean for the Government and the risk of investor flight. We must understand that Mexico has always been a country that has been led by economic power. With its attitude towards NAICM, it aims to clearly mark the line of separation between political and economic power, making it clear that the era of economic power is over. A second reason is that NAICM was going to be the PRI's inheritance and López Obrador probably seeks to destroy any subject of association of this macro project with the party he intends to bury.

REFERENCES

[1] CONCAMIN Document "Airport Proposals" 2018.

[2] Personal interviews with Francisco Cervantes and José Navalón.

[Justin Vaïsse, Zbigniew Brzezinski. America's Grand Strategist. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, 2018. 505 p.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

|

Zbignew Brzezinski, National Security Advisor under Jimmy Carter, is one of the great names in American foreign policy in recent decades. In some respects comparable to Henry Kissinger, who also went directly from the University – where both were colleagues – to the Administration, the latter's greater renown has sometimes obscured the degree program by Brzezinski. Justin Vaïsse's biography, written with access to documentation staff by Brzezinski and first published in French two years ago, highlights the singular figure and thought of someone who had a continuous presence in the discussion about U.S. action in the world until his death in 2017.

Born in Warsaw in 1928 and the son of a diplomat, Brzezinski moved with his family to Canada during World War II. From there he went to Harvard and immediately rose to prominence in the academic community of the United States, where he became a naturalized citizen and lived the rest of his life. If in the 1940s and 1950s, the leading positions in the Administration were nurtured by an older generation that had led the country into war and established the new world order, in the following decades a new world order emerged. group of statesmen, in many cases coming out of the main American universities, who at that time had acquired an unprecedented preeminence in the gestation of political thought.

This was the case of Kissinger, who was born in Germany and also emigrated during the war, who was first National Security Advisor and then Secretary of State under Richard Nixon, and also under Gerald Ford. The next president, Jimmy Carter, brought Brzezinski, who had advised him on international issues during the election campaign, to the White House. The two professors maintained a respectful and at times cordial relationship, although their positions, ascribed to different political camps, often diverged.

For biographical reasons, Brzezenski's original focus—or Zbig, as his collaborators called him—to overcome the difficulty of pronouncing his surname– was in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. From relatively early on he came to the conclusion that the USSR would be incapable of maintaining the economic pulse with the West, so he advocated "peaceful engagement" with the Eastern bloc as a way to accelerate its decomposition. That was the doctrine of the Johnson, Nixon, and Ford administrations.

However, since the mid-1970s, the USSR faced its evident decline with a flight forward to try to re-establish its international power, both in terms of strategic weapons and in its presence in the Third World. Brzezinski then moved to a tougher stance on Moscow, earning him frequent clashes with other figures in the Carter administration, especially Secretary of State Cyrus Vance. Carter had arrived at the White House in January 1977 with some speech appeasement, while remaining belligerent in terms of human rights. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 reinforced the thesis by Brzezinski.

Carter's short presidency left little room for the committee Homeland Security will score special wins. The greatest, although joint work of the presidential team, was the signature of the Camp David accords between Israel and Egypt. But the fiasco of the attempted rescue of the hostages at the Tehran Embassy, which was not Brzezinski's direct responsibility, weighed down an administration that cannot have a second term.

Situated on the right of the Democratic Party, Brzezinski is described by Vaïsse as a "fellow traveler" of the neoconservatives (the Democrats who went over to the Republican side demanding a more robust defense of U.S. interests in the world), but without being a neoconservative himself (in fact, he did not break with the Democratic Party). In any case, he always stressed his independence and was difficult to pigeonhole. "He was neither a warmonger nor a pacifist. It was hawk and dove at different times," says Vaïsse. For example, he opposed the first Gulf War, preferring extreme sanctions, but was in favor of intervening in the Balkan War.

After leaving the Administration, Brzezinski joined the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington and maintained an active production of essays.

essay / Manuel Lamela

The skill to communicate, to weave alliances, to generate a narrative... These are characteristics of what is understood today as public diplomacy. Although it covers a wide variety of topics and areas, we can say that we are referring to power in its communicative facet, for which States compete in a degree program of ideas in order to appropriate the "story" and generate greater influence on a global scale. This struggle for the dominance of thought is not new, but in the last half of the twentieth century, concepts were generated to illustrate this conflict between states, which perhaps before the Cold War was in the background, and they appeared programs of study To analyze this subject of strategies. Despite this, it is enough to take a look at the classics to see clear references to what we currently understand as Public Diplomacy; thus, in works such as Sun Tzu's "Art of War", great importance and value is given to information, both internal and external, and its control is presented as synonymous with triumph in most cases.

Despite the novelty of the concept, Public Diplomacy has undergone several changes and transformations with the entrance of the new century. Along with the importance of non-state actors already present in the past century, we now find a significant increase in the weight that individuals have when it comes to shaping or influencing the policies of their states. The increase is undoubtedly due to the emergence and "democratization" of the internet and, more recently, to the total dependence that exists in populations on the use of social networks. Leaving aside the discussion On whether social networks bring benefits or rather their uncontrolled use generates deficits, which is not relevant in this analysis, what is clear is that social networks create a clear status of vulnerability conducive to state intervention and control, both domestic and foreign.

Given this metamorphosis in terms of diplomacy, various concepts have begun to be coined, such as diplomacy in the United States. network, cybersecurity diplomacy, etc., which are currently present in most State strategies and which encompass the phenomena discussed in the previous paragraph. Within these new strategic plans, think tanks acquire great relevance and importance as generators of ideas and shapers of public opinion, given their hybrid nature of bringing together internship with theory and its mission statement to bring the foreign policy of its various states closer to the general public. Think tanks are, without a doubt, a clear example of soft power exercise. They position themselves as ideological pillars in the construction of new narratives, generating a competitive advantage over the rest.

Anglo-Saxon History and Leadership

Anglo-Saxon hegemony in cementing the values and ideas that constitute the liberal international order is closely related to the origins of the first think tanks and their role within those societies. Modern think tanks emerged during World War II as safe rooms where the U.S. military could develop and plan war strategies. Rand Corporation was founded in 1948 with the goal of promote and protect U.S. interests abroad. Funded and sponsored by the Administration, RAND will inspire and serve as an example for the emergence of new think tanks linked to the U.S. government. Although most of the renowned think tanks appeared in the 1950s, there are several previous examples, both in American and British society, that illustrate in a more obvious way the reason for their leadership in the degree program of idea generation.

At the end of the 19th century, the Fabian Society was founded in the United Kingdom, a syndicalist organization that laid the foundations for the creation of the Labour Party. On the other side of the Atlantic, examples abound: the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) and the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, created by former President Herbert Hoover, emerged prior to the 1920s and exemplify the importance of this subject of associations in American society. But if there is one case worth highlighting, it is that of the Brookings Institution, which was founded in 1916 under the name of the Institute for Government Research (IGR). This philanthropic corporation is one of the first private organizations dedicated to the study and analysis of public policies at the national level; Over the years, its importance and relevance will increase until it becomes the most prestigious and influential think tank in the world.

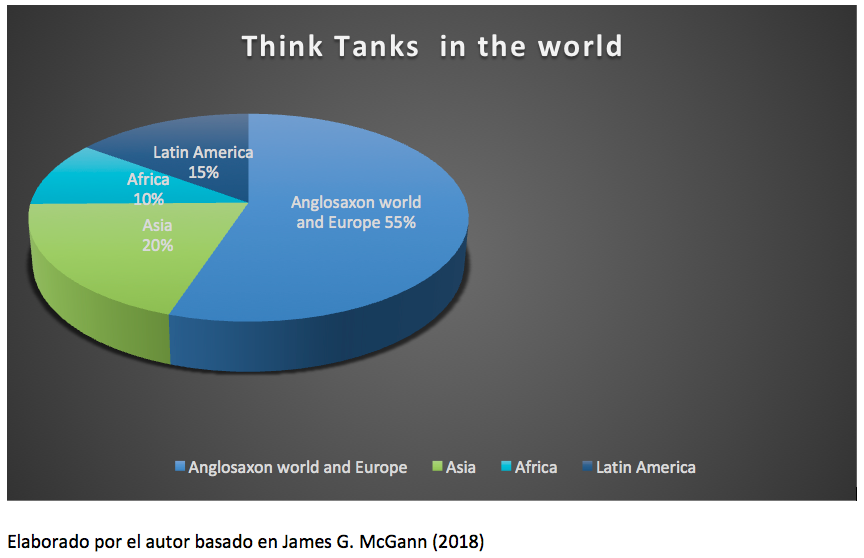

From the 1980s onwards, the phenomenon of the think tank multiplied and expanded to continental Europe, where associations dedicated to analysis and analysis began to be created. research in those fields. Intellectual production in the old continent had been worryingly scarce after the war. So the need to get the machine of ideas back into operation was vital to make sense of the new united Europe and to gain some independence from the Anglo-Saxon world. Today, 55% of the world's think tanks are spread across the US and Western Europe.

With the entrance In the turn of the century, we have seen a significant increase in the issue think tanks on the Asian continent, with the mission statement to rename and redirect Western ideas and even to generate their own ideas, which is popularly known as the "Asian Way". Undoubtedly, the emergence of China as a major world power is essential in the growth of think tanks in Asia. The "sleeping dragon" seeks to consolidate its global position with the creation of a new diplomacy that exports the statement of core values China to all corners of the world, a process in which the New Silk Road will play a fundamental role as a distribution channel. Along with China, the other threat to Western dominance is Russia, which, thanks to its high quality in terms of human capital in matters of intelligence and diplomacy, always positions itself as a fierce competitor, despite the fact that its material resources are smaller. In the case of Latin America and Africa, their contribution continues to be residual and with limited influence at the regional level; the issue think tanks on these two continents account for less than 20% globally.

Types of think tanks

Two different forms of think tanks have already been mentioned in this analysis: the case of RAND as a association closely linked to the U.S. government and the case of Brookings as an independent organization. Within the think tank community there is a great diversity and we can categorize them according to their funding, whether or not they present ideology, their composition, their approach discipline... Today, the most important ranking of think tanks is the one provided annually by the University of Pennsylvania with its report "Think Tanks and Civil Society Program". This report is dedicated to evaluating and classifying the different think tanks that exist today.

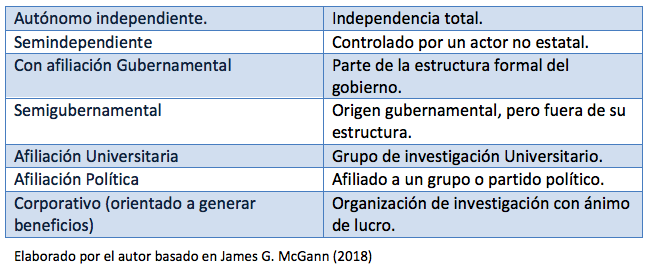

The report It provides the following categories:

|

Think tanks linked to the university or government sphere continue to account for the majority of cases, while think tanks linked to the university or government continue to account for the majority of cases. research profit-making companies are a growing minority.

The Influence of Ideas on U.S. Politics

It is interesting to analyze how Robert D. Kaplan's book "Balkan Ghosts" decisively influenced the American intervention in the Balkan war, and paradoxically led years later, in 2003, to the invasion of Iraq. Kaplan himself, in another of his great works, "The Revenge of Geography," blames the upper echelons of American society for being infected by an unbridled idealism that resulted in underestimating the transcendental role that history and physical geography play in determining the future of nations.

The role played by the various pressures exerted by American think tanks in the invasion of Iraq is the perfect example to illustrate the capital importance that ideas can have when it comes to conducting a state's foreign policy.

Originally, think tanks were born as advisory bodies aimed at providing financial aid and committee to the U.S. government. With the advance of the Cold War and later with the Internet revolution, the need for ideas and independent policy-making became a primary necessity for the United States, which saw in think tanks the best possible solution to nourish itself from the Internet. committee of experts.

The ability to generate new and original ideas away from the political stratum, together with the educational capacity, are two of the main factors that have led to think tanks being considered as benchmarks when it comes to shaping US foreign policy. The direct influence they have is one of the fundamental characteristics that distinguishes them from those existing in other regions, such as Europe, where they are more tied to the academic field; In the U.S., think tanks have a real impact on state policies. It is in these "factories of thought" that the values and ideas with which they will try to sweeten foreign policy and thus expand their sphere of influence to all corners of the globe are built. The mission statement Identifying and solving future problems and conflicts is another of the main tasks of think tanks. They do not always consider themselves government allies and often lead the fiercest criticism; In any case, the autonomy they enjoy is what makes them perceived as a highly valuable asset within American society.

|

The export of the model to Europe

In Europe, the issue think tanks have multiplied since the 1980s, but their issue and relevance are still very distant from the Anglo-Saxon world. In the list of the most important think tanks created by the University of Pennsylvania, only two belong to the European Union: the Institut Français des Relations Internationales and the Belgian Bruegel. The model The American think tank has been both praised and criticized, and the option of imitating it has been discussed in many countries and carried out in many others. Critics of its implementation believe that history and tradition play a fundamental role in making it extremely difficult to export the product. model.

Traditionally, in Europe, universities have been responsible for developing the statement of core values European, and in the past they were very successful in making Europe the vanguard of humanity. Today, however, Europe does not enjoy the leading role it had in other historical periods; the fact is that it has been ideologically outmaneuvered by the United States and has had no choice but to commune with the latter in order to confront greater threats. The latter, together with the greater complexity of the problems in the current panorama and the status In the European Union, it is necessary to renew the European social contract and generate a new narrative that brings European citizens together around a new cause, with the spirit of the Treaties of Rome as a great reference and starting point.

To carry out such an arduous task, think tanks are presented as one of the possible solutions and tools of financial aid. Given its nature of bringing together academia and politics, the creation of new ideas and values that revitalise European society will allow us to aspire to higher qualities. Another key factor is the flexibility of the model think tank, which will generate greater accessibility within civil society, making citizens feel involved and that, ultimately, written request, political participation increases, so that bonds of trust are strengthened rather than broken, as is predicted to happen. As we mentioned in the U.S. case, the value of educational it is another of the main characteristics and will serve as a solution to several of the problems that plague Europe today, such as the rise of extremist parties of different stripes.

Europe has a duty to generate a narrative with which its citizens can identify, and without a doubt the power of ideas will play a fundamental role in the success or failure of this task.

The think tank phenomenon is already one of the models on which the public diplomacy of various States gravitates. The eternal conflict to dominate the world's spheres of thought will continue to be present, so think tanks will continue to grow and develop, gaining more and more relevance at the international level. In the hierarchy of dominance, ideas occupy the last rung, behind individuals, physical geography, and history; However, since ideas are a pure human intellectual creation, they constitute a force of control and movement of the first step, the individuals.

Bibliography

Diego Mourelle. (2018). Think tanks: the diplomacy of ideas. 4/11/2018, from The World Order website.

Cristina Ariza Cerezo. (2016). The American Ideological Landscape: The Case of the Foreign Policy Board. 1/11/2018, from IEEE website.

Katarzyna rybka-iwanska . (2017). 5 reasons why Think tank are soft power tools. 1/11/2018, from USC Center for Public Diplomacy website.

Robert D. Kaplan. (1993). The Balkan Ghosts: A Journey to the Origins of the Bosnia-Kosovo Conflict. United States: S.A. Ediciones B.

Robert D. Kaplan. (2012). The Revenge of Geography. United States: RBA Books.

Pedro Baños. (2018). World Domination: Elements of Power and Geopolitical Keys. Spain: Ariel.

Pedro Baños. (2017). This is how the world is dominated. Unveiling the keys to world power. Spain: Arial.

Hak Yin Li. (2018). The evolution of Chinese public diplomacy and the rise of Think tanks. 1/11/2018, from Springer Link website.

Lars Brozus and Hanns W. Maull. (2017). Think tanks and Foreign Policy. 1/11/2018, from Oxford politics website.

James G. McGann. (2018). 2017 Global Go To Think tank Index Report. 1/11/2018, from University of Pennsylvania website.

Sun Tzu. (2014). Art of War. Spain: Plutón Ediciones.

Against a backdrop of rising populism, the standoff between Brussels and Rome is decisive for the future of the EU

In a measure unparalleled in the history of the Union, the European Commission has rejected the national budgets presented by the populist Italian government, because they do not tend to meet the deficit targets set. Neither Brussels nor Rome seem to have any intention of abandoning their positions, so an institutional confrontation threatens the European horizon.

▲ Giuseppe Conte, President of the Italian Government, with Vice-Presidents Luigi di Maio (left), leader of the 5-Star Movement, and Mateo Salvini (right), leader of the Northern League [Government of Italy]

article / Manuel Lamela

After seven months in government, the coalition formed by the 5-Star Movement and the Northern League have fulfilled what they promised and initiated, with the presentation of the budget of the Italian Republic, a process of confrontation and defiance with the European Union (EU). The authorities in Brussels accuse Italy of irresponsibly breaking the bonds of trust that forge and give meaning to the country. project European.

On October 16, Giuseppe Conte's executive presented a budget with a deficit forecast of 2.4%; While it is true that the figure is below the 3% limit set by the rules and regulations triples the amount previously agreed between Rome and the EU. Moreover, if Italy's public debt is 131% of GDP, making it the second highest in the monetary union, surpassed only by Greece, the new budget It will only increase it, as it aims to significantly increase the expense public.

The rise of the expense it seems to obey the populist interests of the leader of the Northern League and Minister of the Interior, Mateo Salvini, who has made no secret of his intention to seek support in the most fractured sectors of Italian society. Cultivating victimhood vis-à-vis Europe may yield a certain political return, but the example of Greece sample That attitudes of that subject they often end in tragedy, greatly weakening the state in the face of another possible debt crisis.

At the end of October, the European Commission rejected the draft Italian Budget –refund the budget of a Member State was an unprecedented act – and urged Rome to send a revised version within three weeks at the latest. The decision does not close the door to dialogue and negotiations, as indicated in his explanation of what happened by the Commissioner for Economic Affairs, Pierre Moscovici; "Today's opinion should come as no surprise, as the project of budget of the Italian Government represents a clear and intentional departure from the commitments made by Italy last July. However, our door is not closed. We want to continue our constructive dialogue with the Italian authorities. I welcome Finance Minister Giovanni Tria's commitment to this end and we must move forward in this spirit in the coming weeks."

But Conte's government assures that there is no plan B and that there is no chance of Italy taking a step backwards. Both Mateo Salvini and the leader of the 5-Star Movement, Luigi di Maio, both vice-presidents of the government, defended the Italian position and attacked Brussels claiming that it is normal for it to be unhappy, since it is the first time that Italy has freed itself from the clutches of the Eurogroup when it comes to deciding its economic policy. They also stated that, in their reply, the high school of Commissioners directly attacks the Italian people. And they accused Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker of "only talking to drunk people", something that no doubt sample little respect for institutions.

The tactic of simulating strength and determinism, which both Italian political formations used during the election campaign, is being reciprocated by the rest of the European leaders with an exercise of real power. The request of the Italian Minister of Finance, Giovanni Tria, for Italy to be able to enjoy the same opportunity that Portugal had in the past, when Brussels accepted that the Portuguese Prime Minister, Antonio Costa, did not apply the volume of cuts desired by the Commission, will be stifled by the reckless ways employed by the political leaders of the Italian Republic.

If Italy refuses to follow the recommendations given by the EU, there is a possibility that the Commission will consider imposing fines, which can amount to 0.2% of GDP, for failing to comply with the Stability and Growth Pact. But apart from sanctions, the EU has no veto power, nor does it have any other right skill To avoid entrance in force of the budget Italian. As several experts indicate, it will be the pressure of the markets that will make the Italian measure correct, thus avoiding a direct confrontation between Rome and Brussels that would damage both parties equally. Analysts at Goldman Sachs predict that "Italy's debt needs to get worse in order to exert adequate pressure and force the government to opt for other rhetoric."

Even if the European Commission manages to avoid a confrontation with Italy, it could be exposed to the campaign of victimhood by Italian populist groups, a tactic they already used successfully in the last elections. This is a tactic that is not of Italian creation, since since the crisis of 2008 various groupings and parties emerged with a position clearly opposed to Brussels, accusing the EU institutions of all the ills suffered by European societies. There are several examples; Brexit may be the most notorious given its relevance at the European and international level, but we must not forget the rise of formations such as the National Front in France, the Freedom Party in Austria or Podemos in Spain, the latter party that had its great public launch as a result of the 2015 European Parliament elections.

So far, Europe has not been able to find a way to prevent or neutralize the campaigns of demagoguery that proliferate in Europe today. Although some progress is being made in terms of the EU's communicative power, it is incomprehensible that Brussels is unable to effectively explain the project to the citizens of the Union. This is a deficiency that the project It has been the cause of many of the ills that have affected regional unity in recent decades. In this case, Europe has to contribute data that they are easy to understand for the average Italian citizen and that make him see that the measures adopted by his government will be harmful to Italian society in the near future, no matter how much they are sweetened by messages that respond to empty promises and messianic policies.

Another factor of concern within the Commission is the risk of contagion of the virus generated within the third Economics of the EU (excluding the United Kingdom). At first glance, it may seem possible that other Member States will be attracted to follow in Italy's footsteps; However, European officials say they firmly believe that their tough response to Rome will strengthen the monetary union and even increase integrity in areas such as banking unity. Externally, the decision will show that the EU's budgetary rigour is being met, generating confidence and security in the markets, and finally demonstrating that there is no respite from populist formations within Europe.

ESSAY / María Granados

Most scholars and newspapers (1) claim that the inequality gap is widening across the globe, but few provide an explanation as to why this apparently growing concern occurs, nor do they look into the past to compare the main ideologies regarding potential solutions to such problems (i.e.: the Austrian School of Thought and Keynesianism). The following paper attempts to do so by contrasting interventionist and libertarian approaches, to ultimately give an answer to the question.

Alvin Toffler predicted and described what he called 'The Third Wave', a phenomenon consisting of the death of industrialism and the rise of a new civilisation. He focuses on the interconnection of events and trends, (2) which has often been ignored by politicians and social scientists alike. Notwithstanding, J.K. Galbraith points out that the economy is shaped by historical context, and attempts to provide an overview of the main ideas that have given birth to current economic policies; (3) while Landes's focus on the past suggests inequality is not a new phenomenon. (4) Hence, its evolution cannot be overlooked: On the one hand, it led Marx to proclaim that private capital flows invariably lead to property concentration in consistently fewer hands; on the other hand, it led Kuznets to believe that modern economic growth would make developed countries to reach out geographically, spreading process to developing countries thanks to major changes in transport and communication. (5) First and foremost, we shall delve into the why question, sustained by the premise that there is, in fact, inequality, which sets up the foundation for economic studies. (6) Piketty asserts that 'arbitrary and unsustainable inequalities' are generated 'when the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of growth of output and income'. An advocator for open markets and the general interest, he rejects protectionism and nationalism, (7) but is it possible to establish justice through capitalism?, and, more importantly, is capitalism the most suitable system to do so?

Famous liberal philosopher Adam Smith wrote on the matter of state intervention that public policy should only be used insofar as it stimulates economic growth. (8) Freedom of trade made economies specialise through the division of labour, and so it resulted on low prices and an abundant supply of marketable products. The critique on corporations, state-chartered companies, and monopolies, made him conclude that the State should control (9) common defence, the administration of justice, and the provision of necessary public works. Contrary to popular belief, he was also in favour of a proportionate income tax. (10) David Ricardo added that a tax on land rents was necessary to prevent landowners from an increase share of output and income. In the nineteenth century, Marx pursued the destruction of the inevitably accumulated private capital. In the same period, realist theories (11) were embraced by Müller and List, among others, who viewed the state as a protector for the citizens, the equality provider. What all of the aforementioned theories have in common is that the State does play a role to a certain extent on the prevention of 'unfairness'. (12) Although thinkers may well be a product of their times, John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich August Von Hayek have heavily influenced current policies regarding inequality. Arguably, their thoughts stem from the above-mentioned ideas: the input of Marx's Capital in the Keynesian welfare state is contrasted with Smith's liberal approach ('let the invisible hand be') Hayek embraced. During the Great Depression, the preference for liquidity made Keynes focus on the shortage of the demand, to suggest that the corrective action of the government, borrowing and spending funds, was the best way out of the crisis. Several concepts were born or renewed, such as public work, or the social security system, and, more importantly the 'deliberate deficit'. His theory regarded the deliberate unbalance of public budget so that more money would flow into the economy, sustaining demand and employment. (13)

Libertarians would argue that Ricardo failed to foresee that technological progress was going to diminish the dependence on agriculture, therefore decreasing and stabilising land price. Marx also rejected the likelihood of a long-lasting technological development. The latter challenged his ideas, since an increase in productivity and efficiency led to higher salaries and better living conditions, providing more opportunities for the workers. Indeed, with industrialisation came an improvement in the essentials of life. Mitchell, Schumpeter and Robbins, who studied the business cycle, theorised that the economy was a tendency whose problems had no prevention or cure. Thus, inequality had to be allowed to run its course, since it would eventually decrease. In the Post-Keynesian Revolution, the interaction of the wage-price spiral caused inflation. Hayek rhetorically asked the interventionists: 'in our endeavour consciously to shape our future in accordance with high ideals, we should in fact unwittingly produce the very opposite of what we have been striving for?' (14) The OPEC crisis in 1973 made governments apply the Austrian School to WIN, (15) removing any obvious impediments to market competition (i.e.: government regulation). Milton Friedman, in favour of the classical competitive market system, followed Hayek's liberalism. He did write about the negative income tax, consisting of securing a minimum income for all by controlling money supply; nonetheless, he agreed with what Hayek stated in 1945: The more the state organises, plans and intervenes, the more difficult it is for the individual to choose freely, to plan for itself. For Hayek, private property was 'the most important guarantee of freedom'. The division of the means of production amongst independent citizens was his concept of fairness. (16) Professor of Economics Walter E. Williams introduces The Road to Serfdom explaining Hayek's underlying three premises: If using one individual to serve the purpose of another is morally wrong (slavery), taking money from one individual to serve the purpose of another is just as wrong; collectivists or interventionists cannot ignore that free markets produce wealth; and men cannot know or do everything, thus, when the government plans, it assumes to know all the variables. (17)

In 1945, when Hayek challenged the Keynesian perspective, multilateralism arose, giving birth to institutions at the global and regional levels. (18) Currently, whilst there is a tendency to focus on 'global' problems and solutions, Piketty (19) asserts that globalised capitalism can only be regulated through regional measures, stating that 'unequal wealth within nations is more worrisome than unequal wealth between nations.' Specifically, he proves that salaries and output do not catch up with past wealth accumulation. He believes that taxing capital income heavily could potentially kill entrepreneurial activity, and decides that the best policy would be a progressive annual tax on capital. Despite Hayek's premise being the unknown, thereof disgraceful consequences of interventionism; Stiglitz disbelieves that trickle-down economics will address poverty, considering that it is precisely the lack of information what makes the 'invisible hand' fail. Neoliberal assumptions are heavily critisised by Stiglitz, who evaluates the role of the IMF and other international economic institutions' performance, concluding that their programs have often left developing countries with more debt and a more corrupt, richer, ruling government. Moreover, good management ultimately depends on embracing the particular and unique characteristics of each country's economy. (20) At this point, one could ask itself, is justice a biased concept of the west? Landes claims the rich (in IPE, developed countries) will solve the problem of pollution, for instance, because it is them who have more to lose. (21) This could result in a natural redistribution of wealth. By contrast, he demonstrates that the driving force of progress was seen as 'Western' on the realms of education, thinking and technique; until the uneven dissemination made people reject it. (22) The egalitarian society is seemingly in between both of the main economic branches previously discussed: It includes the free will of the rich to tackle current problems the so-called globalization poses; (23) the free-will of developing states to apply national solutions to national problems, and the impulse of international cooperation and regional political integration.

To conclude, history evidences most economists, thinkers and scholars resort to the state to try to distribute wealth evenly. The way they portray the same problem makes them disagree on the way to solve it, but there is an overall agreement on the need to intervene to a certain extent to prevent the inequality gap from broadening. In Galbraith's words: 'Economics is not, as often believed, concerned with perfecting a final and unchanging system. It is in a constant and often reluctant accommodation to change.' (24) On this quest for justice, it may be worth realising that the concept of unfairness cannot be taken for granted.

References

1. E.g.: Lucas Chancel in The Guardian in Jan. 2018, Piketty (2014), Ravenhill (2014), David Landes (1999).

2. Toffler, Alvin (1980). The Third Wave. New York: Bantam Books.

3. Galbraith, John Kenneth. (1987). Economics in Perspective. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Trade and Reference.

4. Landes, David. (1999). The Wealth and Poverty of Nations. London: Abacus.

5. Nobel Lectures, Economics 1969-1980, publisher Assar Lindbeck, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore, 1992.

6. The aim of the subject being the allocation of scarce resources (according to e.g.: L. Robbins).

7. Piketty, Thomas. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press. p. 7

8. Galbraith, John Kenneth. L.C. F.F. 8

9. E.g.: through the imposition of tariffs or taxes following the canon of certainty, convenience, and economical to assess and raise.

10. Read Smith, A. (1776). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. 1998 edition. Milano: Cofide. Book V: On the Revenue of the Sovereign or Commonwealth; Chapter II: On the Sources of the General or Public Revenue of the Society; Part II: On Taxes. I.

11. For more on the theories that shaped economic thought, read Paul, Darel, and Amawi, Alba, (Eds.). 2013. The Theoretical Evolution of International Political Economy: A Reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press. See p. 16-19 and p. 153 for Realism, p. 95 and 102 for Friedrich List.

12. Note: Even in socialism, prior to the State's dissolution, workers had to become the ruling government to ensure the process ensued.

13. Keynes, John Maynard. (1936). The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money. Cambridge: Palgrave MacMillan.

14. Hayek, Friedrich A. (1945). The Road to Serfdom. Reader's Digest. Combined edition, 2015: The Institute of Economic Affairs. p. 40

15. Whip Inflation Now

16. Ibid., p. 41

17. Ibid. Introduction

18. Read Ravenhill, John. (2014). Global Political Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

19. Pikkety, Thomas. L.C., pp. 303-304, 339 f.f.

20. Stiglitz, Joseph. (2003). Globalization and its Discontents. London: Penguin.

21. Landes, David. L.C. p. 516

22. Ibid., p. 513

23. Hirst develops the following points: In the 1870-1914 period there was as much economic integration as now; most transnational corporations are not truly 'global'; the Third World is becoming marginalised with regards to the movement of capital, employment and investment; and supranational regionalisation is a more relevant trend than that of Globalization. Hirst, Paul, et al. (2009). Globalization in Question. Oxford: Polity.

24. Galbraith, J.K. l.c. Chapter 22, p. 326.

Bibliography

Chancel, Lucas (coordinator). World Inequality Report. Wid.world: Executive report. World Inequality Lab, 2018, pp. 4–16.

Galbraith, John Kenneth. (1987). Economics in Perspective. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Trade and Reference.

Hayek, Friedrich August (1945). The Road to Serfdom. Reader's Digest. Combined edition, 2015: The Institute of Economic Affairs.

Hirst, Paul, et al. (2009). Globalization in Question. Oxford: Polity.

Keynes, John Maynard. (1936). The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money. Cambridge: Palgrave MacMillan.

Landes, David. (1999). The Wealth and Poverty of Nations. London: Abacus.

Nobel Lectures, Economics 1969-1980, publisher Assar Lindbeck, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore, 1992.

Paul, Darel, and Amawi, Alba, (Eds.). 2013. The Theoretical Evolution of International Political Economy: A Reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Piketty, Thomas. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press.

Ravenhill, John. (2014). Global Political Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.