Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs World order, diplomacy and governance .

COMMENT / Carlos Jalil

Covid-19 has forced many states to take extraordinary measures to protect the welfare of their citizens. This includes the suspension of certain human rights on grounds of public emergency. Rights such as freedom of movement, freedom of expression, freedom of meeting and privacy are affected by state responses to the pandemic. We therefore ask: Do states unduly affect freedom of expression when combating fake news? Do they unduly restrict our freedom of movement and meeting or even deprive us of our liberty? Do they infringe on our right to privacy with new tracking apps? Is this justified?

To protect public health, human rights treaties allow states to adopt measures that may restrict rights. article agreement 4 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and article 15 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) provide that in situations of public emergency that threaten the life of the nation, states may take measures and derogate from their treaty obligations. Similarly, article 27 of the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), allows states parties to fail to derogate from their obligations in emergency situations that threaten the independence or security of the nation.

During the pandemic, some states have declared a state of emergency and, because of the impossibility of respecting certain rights, have derogated from their obligations. However, derogations are subject to requirements. General Comment 29 on States of Emergency of the UN Human Rights committee sets out six conditions for derogations, which are similar in the above-mentioned treaties: (1) official proclamation of a state of emergency and public emergency threatening the life of the nation; (2) proportionality required by the requirements of the status in terms of duration, geographical coverage and substantive basis; (3) non-discrimination (however the ECHR does not include this condition); (4) conformity with other international law obligations; (5) formal notification of the derogation to the respective treaty bodies (these must include full information on the measures, their reasons and documentation of laws adopted); and (6) prohibition of derogation from non-derogable rights.

The last condition is particularly important. The aforementioned treaties (ICCPR, ECHR and ACHR) explicitly set out the rights that cannot be derogated from. These, also called absolute rights, include, inter alia: right to life, prohibition of slavery and servitude, principle of legality and retroactivity of law, and freedom of conscience and religion.

However, derogations are not always necessary. There are rights that, on the contrary, are not absolute and have the inherent possibility of being limited, for which it is not necessary for a state to derogate from its treaty obligations. This means that the state, for public health reasons, may limit certain non-absolute rights without the need to give notice of derogation. These non-absolute rights are: the right to freedom of movement and meeting, freedom of expression, the right to liberty staff and privacy. Specifically, the right to freedom of movement and association is subject to limitations on grounds of national security, public order and health, or the rights and freedoms of others. The right to freedom of expression may be limited by respect for the rights or reputation of others and by the protection of national security, public order and public health. And the rights to freedom of expression staff and privacy may be subject to reasonable limitations in accordance with the provisions of human rights treaties.

Despite these possibilities, countries such as Latvia, Estonia, Argentina and Ecuador, which have officially declared a state of emergency, have resorted to derogation. Consequently, they have justified Covid-19 as an emergency threatening the life of the nation, notifying the United Nations, the Organisation of American States and Europe's committee of the derogation from their international obligations under the aforementioned treaties. In contrast, most states adopting extraordinary measures have not proceeded with such derogation, based on the inherent limitations of these rights. Among them are Italy and Spain, countries seriously affected, which have not derogated, but have applied limitations.

This is an interesting phenomenon because it demonstrates the differences in states' interpretations of international human rights law, also subject to their national legislatures. There is clearly a risk that states applying limitations abuse the state of emergency and violate human rights. It may therefore be that some states interpret derogations as reflecting their commitment to the rule of law and the principle of legality. However, human rights bodies are also likely to find the measures adopted by states that have not derogated consistent with the status pandemic. Excluding, in both cases, situations of torture, excessive use of force and other circumstances affecting absolute rights.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, courts and tribunals are likely to decide whether the measures adopted were necessary. But in the meantime, states should consider that extraordinary measures adopted should be temporary, in line with appropriate health conditions and within framework of the law.

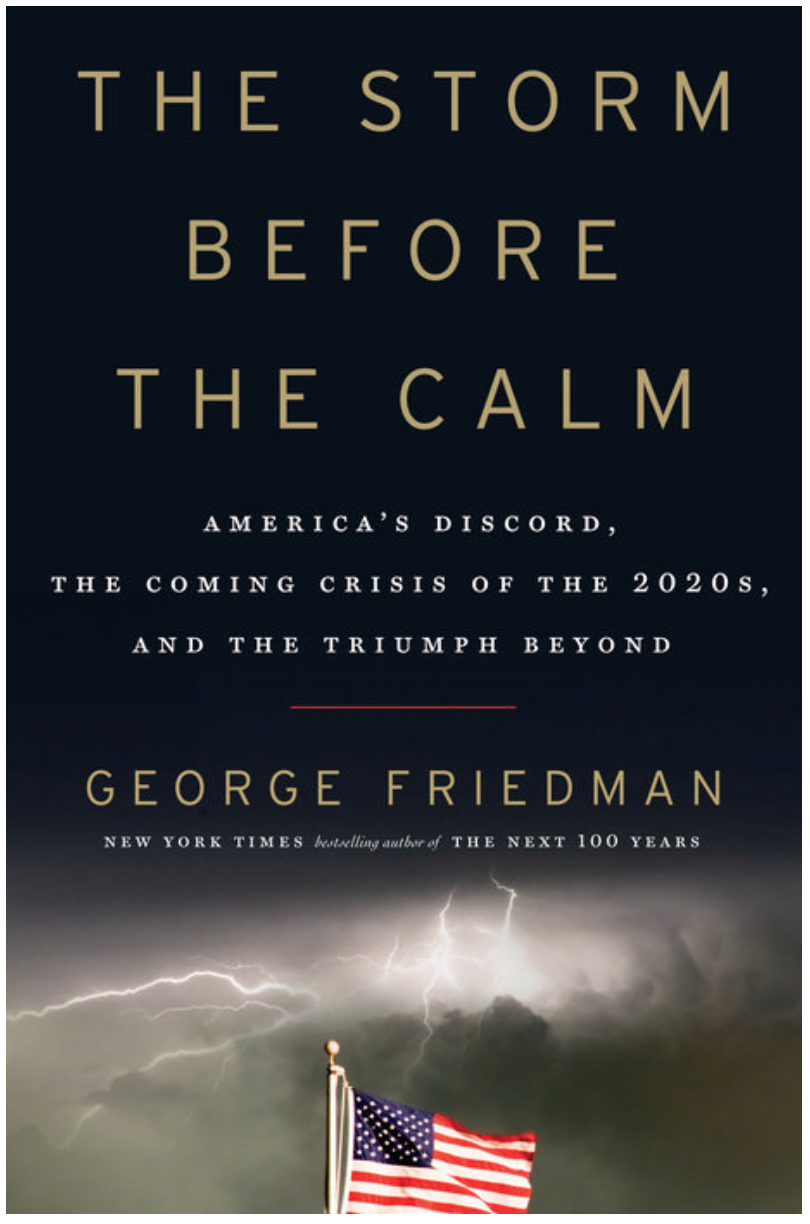

[George Friedman. The Storm Before the Calm. America's Discord, the Coming Crisis of the 2020s, and the Triumph Beyond. Doubleday. New York, 2020. 235 pp.]

review / E. Villa Corta, E. J. Blasco

The degree scroll of the new book by George Friedman, the driving force behind the geopolitical analysis and intelligence agency Stratfor and later creator of Geopolitical Futures, does not refer reference letter to the global crisis created by the Covid-19 pandemic. When he speaks of the crises of the 2020s, which Friedman has been anticipating for some time in his commentaries and now explains at length in this book, he is referring to deep and long-lasting historical movements, in this case confined to the United States.

The degree scroll of the new book by George Friedman, the driving force behind the geopolitical analysis and intelligence agency Stratfor and later creator of Geopolitical Futures, does not refer reference letter to the global crisis created by the Covid-19 pandemic. When he speaks of the crises of the 2020s, which Friedman has been anticipating for some time in his commentaries and now explains at length in this book, he is referring to deep and long-lasting historical movements, in this case confined to the United States.

Beyond the current pandemic, therefore, which is somewhat circumstantial and not addressed in the text (its composition is previous), Friedman predicts that the US will reinvent itself at the end of this decade. Like a machine that, almost automatically, incorporates substantial changes and corrections every certain period of time, the US is preparing for a new leap. There will be a prolonged crisis, but the US will emerge triumphant, Friedman predicts. US decline? Quite the opposite.

Unlike Friedman's previous books, such as The Next Hundred Years or Flashpoints, this time Friedman moves away from Friedman's global geopolitical analysis to focus on the US. In his reflection on American history, Friedman sees a succession of cycles of roughly equal length. The current ones are already in their final stages, and the reinstatement of both will coincide in the late 2020s, in a process of crisis and subsequent resurgence of the country. In the institutional field, the 80-year cycle that began after the end of World War II is coming to an end (the previous one had lasted since the end of the Civil War in 1865); in the socio-economic field, the 50-year cycle that began with Ronald Reagan in 1980 is coming to an end (the previous one had lasted since the end of the Great Recession and the arrival of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the White House).

Friedman does not see Donald Trump as the catalyst for change (his effort has simply been to recover the status created by Reagan for the class average working class, affected by unemployment and loss of purchasing power), nor does he believe that whoever replaces him in the coming years will be the catalyst. Rather, he places the turnaround around 2028. The change, which is taking place in a time of great turmoil, will have to do with the end of the technocracy that dominates American political and institutional life and with the creative disruption of new technologies. The author wants to denote the US's skill ability to overcome adversity and take advantage of "chaos" in order to achieve fruitful growth.

Friedman divides the book into three parts: the creation of the nation as we know it, the cycles we have gone through, and the prognosis for the one to come. In this last part he presents the challenges or adversities that the country will have to face.

As for the creation of the country, the author reasons about the subject government created in the United States, the territory in which the country is located and the American people. This last aspect is perhaps the most interesting. He defines the American people as a purely artificial construct. This leads him to see the US as a machine that automatically fine-tunes its functioning from time to time. As an "invented" country, the US reinvents itself when its cycles run out of steam.

Friedman presents the training of the American people through three overlapping types: the cowboy, the inventor and the warrior. To the cowboy, who seeks to start something completely new and in an "American" way, we owe especially America's unique social construct. To the inventor belongs the drive for technological progress and economic prosperity. And the warrior condition has been present from the beginning.

The second part of the book deals with the aforementioned question of cycles. Friedman considers that US growth has been cyclical, a process in which the country reinvents itself from time to time in order to continue progressing. After reviewing the periods so far, he locates the next big change in the US in the decade that has just begun. He warns that the gestation of the next stage will be complicated by the accumulation of events from past cycles. One of the issues that the country will have to resolve concerns the paradox between the desire to internationalise democracy and human rights and that of maintaining its national security: "liberating the world" or securing its position in the international sphere.

The present moment of change, in which agreement with the author the institutional and the socio-economic cycle will collide, is a time of deep crisis, but will be followed by a long period of calm. Friedman believes that the first "tremors" of the crisis were felt in the 2016 elections, which showed a radical polarisation of US society. The country will have to reform not only its complex institutional system, but also various socio-economic aspects.

This last part of the book - devoted to solving problems such as the student debt crisis, the use of social networks, new social constructions or the difficulty in the sector educational- is probably the most important. If the mechanicity and automatism in the succession of cycles determined by Friedman, or even their very existence, are questionable (other analyses could lead other authors to consider different stages), the real problems that the country is currently facing are easily observable. So the presentation of proposals for their resolution is of undoubted value.

![Tourist town in Gjirokastër district, southern Albania [Pixabay]. Tourist town in Gjirokastër district, southern Albania [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/albania-ue-blog.jpg)

Tourist population in Gjirokastër district, southern Albania [Pixabay].

ESSAY / Jan Gallemí

On 24 November 2019, the French government of Enmanuel Macron led the veto, together with other states such as Denmark and the Netherlands, of the accession of the Balkan nations of Albania and North Macedonia to the European Union. According to the president of the French Fifth Republic, this is due to the fact that the largest issue of economic refugees entering France are from the Balkans, specifically from the aforementioned Albania. The latter country applied to join the European Union on 28 April 2009, and on 24 June 2014 it was unanimously agreed by the 28 EU countries to grant Albania the status of a country candidate for accession. The reasons for this rejection are mainly economic and financial.[1]. There is also a slight concern about the diversity that exists in the ethnographic structure of the country and the conflicts that this could cause in the future, not only within the country itself but also in its relationship with its neighbours, especially with the Kosovo issue and relations with Greece and North Macedonia.[2]. However, another aspect that has also been explored is the fact that Albania's accession would mean the EU membership of the first state in which the religion with the largest number of followers is Islamic, specifically the Sunni branch, issue . This essay will proceed to analyse the impact of this aspect and observe how, or to what extent, Albanian values, mainly because they are primarily Islamic in religion, may combine or diverge from those on which the common European project is based.

Evolution of Islam in Albania

One has to go back in history to consider the reasons why a European country like Albania has developed a social structure in which the religion most professed by part of the population is Sunni. Because of the geographical region in which it is located, it would theoretically be more common to think that Albania would have a higher percentage of Orthodox than Sunni population.[3]. The same is true for Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. This region was originally largely Orthodox Christian in the south (like most Balkan states today) due to the fact that it was one of the many territories that made up the Byzantine Empire until the 13th century, when the nation gained its independence. However, the reason why Islam is so present in Albania, unlike its neighbouring states, is that it was more religiously influenced by the Ottoman Empire, the successor to the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire fell in 1453 and its territories were occupied by the Ottomans, a Turkish people established at that time on the Anatolian peninsula. According to historians such as Vickers, it was between the 17th and 18th centuries that a large part of the Albanian population converted to Islam.[4]The reason for this, as John L. Esposito points out, was that for the Albanian population, changing their religion meant getting rid of the higher taxes that Christians had to pay in the Ottoman Empire.[5].

Religion in Albania has since been shaped by events. As far as we know from programs of study such as those of Gawrych in the 19th century, Albanian society was then divided mainly into three groups: Catholics, Orthodox and Sunnis (the latter represented 70% of the population). The same century saw the birth of many of the well-known European nationalisms and the beginning of the so-called Eastern crisis in the Balkans. During this period many Balkan peoples revolted against the Ottomans, but the Albanians, identifying with the Ottomans through their religion, initially remained loyal to the Sultan.[6]. Because of this support, Muslim Albanians began to be pejoratively referred to as "Turks".[7]. This caused Albanian nationalism to distance itself from the emerging Ottoman pan-Islamism of Sultan Abdualhmid II. This gave rise, according to Endresen, to an Albanian national revival called Rilindja, which sought the support of Western European powers.[8].

The Balkan independence movements that emerged in the 19th century generally reinforced Christian as opposed to Muslim sentiment, but in Albania this was not the case; as Stoppel points out, both Albanian Christians and Muslims cooperated in a common national goal .[9]. This encouraged the coexistence of both beliefs (already present in earlier times) and allowed the differentiation of this movement from Hellenism.[10]. It is worth noting that at that time in Albania Muslims and Christians were peculiarly distributed territorially: in the north there were more Catholic Christians who were not so influenced by the Ottoman Empire, and in the south Orthodox also predominated because of the border with Greece. On 28 November 1912 the Albanians, led by Ismail Qemali, finally declared independence.

The international recognition of Albania by the Treaty of London meant the imposition of a Christian monarchy, which led to the outrage of Muslim Albanians, estimated at 80% of the population, and sparked the so-called Islamic revolt. The revolt was led by Essad Pasha Toptani, who declared himself the "saviour of Albania and Islam" and surrounded himself with disgruntled clerics. However, during the period of World War I, Albanian nationalists soon realised that religious differences could lead to the fracturing of the country itself and decided to break ties with the Muslim world in order to have "a common Albania", which led to Albania declaring itself a country without an official religion; this allowed for a government with representation from the four main religious faiths: Sunni, Bektashi, Catholic and Orthodox, training . Albanian secularist elites planned a reform of Islam that was more in line with Albania's traditions in order to further differentiate the country from Turkey, and religious institutions were nationalised. From 1923 onwards, the Albanian National congress eventually implemented the changes from a perspective very similar to that of Western liberalism. The most important reforms were the abolition of the hijab and the outlawing of polygamy, and a different form of prayer was implemented to replace the Salat ritual. But the biggest change was the replacement of Sharia law with Western-style laws.

During World War II Albania was occupied by fascist Italy and in 1944 a communist regime was imposed under the leadership of Enver Hoxha. This communist regime saw the various religious beliefs in the country as a danger to the security of the authoritarian government, and therefore declared Albania the first officially atheist state and proposed the persecution of various religious practices. Thus repressive laws were imposed that prevented people from professing the Catholic or Orthodox faiths, and forbade Muslims from reading or possessing the Koran. In 1967 the government demolished as many as 2,169 religious buildings and converted the rest into public buildings. Of 1,127 buildings that had any connection to Islam at the time, only about 50 remain today, and in very poor condition.[11]. It is believed that the impact of this persecution subject was reflected in the increase of non-believers within the Albanian population. Between 1991 and 1992 a series of protests brought the regime to an end. In this new democratic Albania, Islam was once again the predominant religion, but the preference was to maintain the non-denominational nature of the state in order to ensure harmony between different faiths.

Influences from the international arena

Taking into account this reality of Albania as a country with a majority Islamic population, we turn to the impact of its accession to the EU and the extent to which the values of the two contradict each other.

To begin with, if all this is analysed from a perspective based on the theory of "constructivism", such as that of Helen Bull's proposal , it can be seen how Albania from the beginning of its history has been a territory whose social structure has been strongly influenced by the interaction of different international actors. During the years when it was part of the Byzantine Empire, it largely absorbed Orthodox values; when it was occupied by the Ottomans, most of its population adopted the Islamic religion. Similarly, during the de-Ottomanisation of the Balkans, the country adopted currents of political thought such as liberalism due to the influence of Western European powers. This led to a desire to create a constitutionalist and parliamentary government whose vision of politics was not based on any religious morality.[12]. It can also be seen that the communist regime was imposed in a context common to that of the other Eastern European states. At the same time, it also returned to a democratic path after the collapse of the USSR, even though Albania had not maintained good relations with the Warsaw Pact since 1961.

Since Albania's EU candidacy, these liberal values have been strengthened again. In particular, Albania is striving to improve its infrastructure and to eradicate corruption and organised crime. So it can be seen that Albanian society is always adapting to being part of a supra-governmental organisation. This is an important aspect because it means that the country is most likely to actively participate in the proposals made by the European Commission, without being driven by domestic social values. However, this in turn gives a point in favour of those MEPs who argued that the veto decision was a historic mistake. For if it does not alienate the EU, Albania could alienate other international actors. According to MEPs themselves, these could be Russia or China.

However, there are two limitations to this assertion. The first is that since 2012 Albania has been a member of NATO, so it is already partly alienated from the West in military terms. But a second aspect is more important, namely that Albania already tried during the Cold War to alienate itself from Russia and China, but found that this had negative effects as it made it a satellite state. On the other hand, and this is where Islamic values come into play, Albania today is a member of Islamic organisations such as the OIC (Organisation of Islamic Cooperation). Rejection by the EU could therefore mean Albania's realignment with other Islamic states, such as the Arabs or Turkey. Turkey's own government, currently led by Erdogan's party, has a neo-Ottomanist nature: it seeks to bring the states that formerly constituted the Ottoman Empire under its influence. Albania is being influenced by this neo-Ottomanism and a European rejection could bring it back into the fold of this conception.[13]. Moreover, by moving closer to Middle Eastern Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia, Albania would run the risk of assimilating the Islamic values of these territories.[14]These are incompatible with those of the EU because they do not comply with many of the articles signed up to in the 1952 Universal Declaration of Rights.

Islam and the European Union

Another aspect would be to ask in what respects do Islamic values contradict those of the EU? The EU generally claims to be against polygamy, homophobia or religious practices that oppose the dignity of the person. This has generated, among other things, a powerful internal discussion as to whether the hijab can be considered as a internship staff that should not be legally prevented. Many feminist groups are against this aspect as they relate it to family patriarchalism.[15]However, other EU groups claim that this is only a fully respectable individual internship staff and that its abolition would be a gesture of an Islamophobic nature. In any case, as mentioned above, Albania abolished both polygamy and the wearing of the hijab in 1923 as not reflecting the values of Islam in Albania.[16]. In this respect, it can be observed that although Albania is a country with an Islamic majority, this Islam is much more influenced by Europeanist currents than by Eastern ones: that is, an Islam adapted to European customs and whose values are currently more similar to those of the neighbouring Balkan states.

Some MEPs, usually from far-right groups such as Ressamblement National or Alternativ für Deutschland, claim that Islamic values will never be compatible with European values because they are expansionist and radical. Dutchman Geert Wilders claims that the Koran "is more anti-Semitic than Mein Kampf".[17]. In other words, they claim that those who profess Islam are incapable of maintaining good relations with other faiths because the Koran itself speaks of waging war against the infidel through Jihad. As an example, they cite the terrorist attacks that the Islamist group DAESH has provoked over the last decade, such as those perpetrated in Paris and Barcelona.[18]. But these groups should be reminded that a sacred text such as the Koran can be interpreted in many ways and that although some Muslim groups believe in this incompatibility of good relations with those who think differently, the majority of Muslims interpret the Koran in a very different way, just as they do the Bible, even if some very specific groups become irrational.

This is clearly the case in Albania, where since its democratisation in 1991 there has been a national project integrating all citizens, regardless of their different beliefs. Rather, throughout its history as an independent country there has been only one period of religious persecution in Albania, and that was due to the repression of communist authoritarianism. One limitation in this respect might be the Islamic revolution that took place in Albania in 1912. But it is worth noting that this revolution, despite its strong Islamic sentiment, served to overthrow a puppet government; no law was enforced after it to impose Islamic values on the rest. So it is worth noting that Albania's political model is very similar to that of Rawls in his book "Political Liberalism", because it configures a state with multiple values (although there is a predominant one), but its laws are not written on the basis of any of them, but on the basis of common values among all of them based on reason.[19]. This model proposed by Rawls is one of the founding instructions of the European Union and Albania would be a state that would exemplify these same values.[20]. This is what the Supreme Pontiff Francis I said at his visit in Tirana in 2014: "Albania demonstrates that peaceful coexistence between citizens belonging to different religions is a path that can be followed in a concrete way and that produces harmony and liberates the best forces and creativity of an entire people, transforming simple coexistence into true partnership and fraternity".[21].

Conclusions

It can be concluded that Albania's values as an Islamic-majority state do not appear to be divergent from those of Western Europe and thus the European Union. Albania is a non-denominational state that respects all religious beliefs and encourages all individuals, regardless of their faith, to participate in the political life of the country (which has much merit given the significant religious diversity that has distinguished Albania throughout its history). Moreover, Islam in Albania is very different from other regions due to the impact of European influence in the region. Not only that, but the country also seems very willing to collaborate on common projects. The only thing that, in terms of values, would make Albania unsuitable for EU membership would be if, just as it has been influenced by the actors that have interacted with it throughout its history, it were to be influenced again by Muslim states with values divergent from European ones. But this is more likely to be the case if the EU were to reject Albania, as it would seek the support of other allies in the international arena.

The implications of the accession of the first Muslim-majority state to the EU would certainly be advantageous, as it would encourage a variety of religious thought within the Union and this could lead to greater understanding between the different faiths within it. There would be the possibility of a greater presence of Sunni MEPs in the European Parliament and it would help to enhance coexistence within other EU states on the basis of what has been done in Albania, such as in France, where 10 per cent of the population is Muslim. It should also be said that Albania's exemplary multi-religious behaviour would seriously weaken Euroscepticism and also help to foster harmony within the Balkan region. As Donald Tusk has argued, the Balkans must be given a European perspective and it is in the EU's best interest that Albania becomes part of it.

[1] Lazaro, Ana; European Parliament adopts resolution against veto on North Macedonia and Albania; euronews. ; last update: 24/10/2019

[2] Sputnik World; The West's attitude to the spectre of 'Greater Albania' worries Moscow; Sputnik World, 22/02/2018. grade Sputnik World: Care should be taken when analysing this source as it is often used as a method of Russian propaganda.

[3] "Third Opinion on Albania adopted on 23 November 2011". Strasbourg. 4 June 2012.

[4] Vickers, Miranda (2011). The Albanians: a modern history. London: IB Tauris.

[5] Esposito, John; Yavuz, M. Hakan (2003). Turkish Islam and the secular state: The Gülen movement. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press

[6] Gawrych, George (2006). The crescent and the eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874-1913. London: IB Tauris.

[7] Karpat, Kemal (2001). The politicization of Islam: reconstructing identity, state, faith, and community in the late Ottoman state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[8] Endresen, Cecilie (2011). "Diverging images of the Ottoman legacy in Albania". Berlin: Lit Verlag. pp. 37-52.

[9] Stoppel, Wolfgang (2001). Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien). Cologne: Universität Köln.

[10] Gawrych, George (2006). The crescent and the eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874-1913. London: IB Tauris.

[11] Nurja, Ermal (2012). "The rise and destruction of Ottoman Architecture in Albania: A brief history focused on the mosques". Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

[12] Albanian Constituition of 1998.

[13] Return to Instability: How migration and great power politics threaten the Western Balkans. European Council on Foreign Relations. 2015.

[14] Bishku, Michael (2013). "Albania and the Middle East.

[15] García Aller, Marta; Feminists against the hijab: "Europe is falling into the Islamist trap with the veil".

[16] Jazexhi, Olsi (2014)."Albania." In Nielsen, Jørgen; Akgönül, Samim; Alibašić, Ahmet; Racius, Egdunas (eds.) Yearbook of Muslims in Europe: Volume 6. Leiden: Brill.

[17] EFE; The Dutch MP who compared the Koran to 'Mein Kampf' does not withdraw his words. La Vanguardia; 04/10/2010

[18] Khader, Bichara; Muslims in Europe, the construction of a "problem"; OpenMind BBVA

[19] Rawls, John; Political Liberalism; Columbia University Press, New York.

[20] Kristeva, Julia; Homo europaeus: is there a European culture; OpenMind BBVA.

[21] Vera, Jarlison; Albania: Pope highlights the partnership between Catholics, Orthodox and Muslims; Acaprensa

![A woman crosses a bridge in a rural area of Pakistan [Pixabay]. A woman crosses a bridge in a rural area of Pakistan [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-report-blog.jpg)

▲ A woman crosses a bridge in a rural area of Pakistan [Pixabay].

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS REPORT / Naiara Goñi, Roberto Ramírez, Albert Vidal

Download the document [pdf. 1,4MB] [pdf. 1,4MB

Download the document [pdf. 1,4MB] [pdf. 1,4MB

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The purpose of this strategic analysis report is to ascertain how geopolitical dynamics in and around Pakistan will evolve in the next few years.

Pakistani relations with the US will become increasingly transactional after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. As the US-India partnership strengthens to face China, the US will lose interest in Pakistan and their priorities will further diverge. In response, Beijing will remain Islamabad's all-weather strategic partner despite claims that the debt-trap could become a hurdle. Trade relations with the EU will continue to expand and Brussels will not use trade leverage to obtain Human Rights concessions from Islamabad. Cooperation in other areas will stagnate, and the EU's neutrality on the Kashmir issue will remain unchanged.

In Central Asia, Islamabad will maintain positive relations with the Central Asian Republics, which will be based on increasing connectivity, trade and energy partnerships, although these may be endangered by instability in Afghanistan. Relations with Bangladesh will remain unpropitious. An American withdrawal from Afghanistan will most likely lead to an intensification of the conflict. Thanks to connections with the Taliban, Pakistan might become Afghanistan's kingmaker. Even if regional powers like Russia and China may welcome the US withdrawal, they will be negatively affected by the subsequent security vacuum. Despite Pakistani efforts to maintain good ties with both Iran and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), if tensions escalate Islamabad will side with Riyadh. Pakistan's weak non-proliferation credentials will be coupled with a risk of Pakistan sharing its nuclear arsenal with the Saudis.

A high degree of tensions will continue characterising its relations with India, following the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A of the Indian constitution. Water scarcity will be another source of problems in their shared borders, which will be exacerbated by New Delhi's construction of reservoirs in its territory. Islamabad will continue calling for an internationalization of the Kashmir issue, in search of international support. They are likely to fight localised skirmishes, but there is a growing fear that the contentious issues mentioned above could eventually lead to an all-out nuclear war. PM Khan and Modi will be reluctant to establish channels of rapprochement, partly due to internal dynamics of both countries, be it Hindu nationalism or radical Islam.

A glance inside Pakistan will show how terrorism will continue to be a significant threat for Pakistan. As a result of Pakistan's lack of effective control in certain areas of its territory, the country has been used as a base of operations by terrorist and criminal groups for decades, to perpetrate all kinds of attacks and illegal activities, which will not change in the near future. Risks that should be followed closely include the power of anti-Western narratives wielded by radical Islamists, the lack of a proper educational system and an ambiguous counter-terrorism effort. In the midst of this hodgepodge, religion will continue to have a central role and will undoubtedly be used by non-state actors to justify their violent actions, although it is less likely that it will become an instrument for states to further their radical agendas.

Albania and North Macedonia are forced to accept tougher negotiating rules, while Serbia and Montenegro reassess their options.

Brexit has been absorbing the EU's negotiating attention for many months and now Covid-19 has slowed down non-priority decision-making processes. In October 2019, the EU decided to cool down talks with the Western Balkans, under pressure from France and some other countries. Albania and North Macedonia, which had made the work that Brussels had requested in order to formally open negotiations, have seen the rules of the game changed just before the start of the game.

![meeting of the Western Balkans with EU countries, held in London in 2018 [European Commission]. meeting of the Western Balkans with EU countries, held in London in 2018 [European Commission].](/documents/10174/16849987/ue-balcanes-blog.jpg)

▲ meeting of the Western Balkans with EU countries, held in London in 2018 [European Commission].

article / Elena López-Doriga

Since its origins, the European Community has been evolving and expanding its competences through treaties structuring its functioning and aims. issue The membership of the organisation has also expanded considerably: it started with 6 countries (France, Belgium, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) and now consists of 27 (following the recent departure of the United Kingdom).

The most notable year of this enlargement was 2004, when the EU committed itself to integrating 10 new countries, which was a major milestone challenge, given that these countries were mainly from Central and Eastern Europe, coming from the "iron curtain", with less developed economies emerging from communist systems and Soviet influence.

The next enlargement round goal is the possible EU membership of the countries of the Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia). However, at a summit held in Brussels at the end of 2019 to open accession negotiations for new members, some EU countries were against continuing the process, so for the time being the accession of the candidate countries will have to wait. Some EU leaders have called this postponement a "historic mistake".

Enlargement towards Central and Eastern Europe

In May 1999 the EU launched the Stabilisation Process and association. The Union undertook to develop new contractual relations with Central and Eastern European countries that expressed a desire to join the Union through stabilisation agreements and association, in exchange for commitments on political, economic, trade or human rights reform. As a result, in 2004 the EU integrated the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia (the first member from the Western Balkans). In 2007 Bulgaria and Romania also joined the Union and in 2013 Croatia, the second Western Balkan country to join.

The integration of the Western Balkans

Since the end of the Yugoslav wars in late 2001, the EU has played a very prominent role in the Balkans, not only as an economic power in subject reconstruction, but also as a guarantor of stability and security in the region. The EU's goal is in part to prevent the Western Balkans from becoming a security black hole, given the rise of rising nationalism, growing tension between Moscow and Washington, which fuels tensions between ethnic groups in the region, and China's economic penetration of the area. Clearer progress towards Balkan integration was reaffirmed in the Commission's Western Balkans strategy of February 2018 and in the Sofia Declaration following the EU-Western Balkans Summit held in the Bulgarian capital on 17 May 2018. At the Summit, EU leaders reiterated their unequivocal support for the European perspective of the Western Balkans. "I see no future for the Western Balkans other than the EU. There is no alternative, there is no plan B. The Western Balkans are part of Europe and belong to our community," said the then president of the European committee , Donald Tusk.

Official candidates: Albania and Macedonia

Albania applied for EU membership on 28 April 2009. In 2012, the Commission noted significant progress and recommended that Albania be granted the status of candidate, subject to the implementation of a number of outstanding reforms. In October 2013, the Commission unequivocally recommended that Albania be granted membership status candidate . visit Angela Merkel visited Tirana on 8 July 2015 and stated that the prospect of the Balkan region's accession to the European Union (EU) was important for peace and stability. He stressed that in the case of Albania the pace of the accession process depended on the completion of reforms in the judicial system and the fight against corruption and organised crime. In view of the country's progress, the Commission recommended the opening of accession negotiations with Albania in its 2016 and 2018 reports.

On the other hand, the Republic of North Macedonia (former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia) applied for EU membership in March 2004 and was granted country status candidate in December 2005. However, the country did not start accession negotiations because of the dispute with Greece over the use of the name "Macedonia". When this was successfully resolved by the agreement of Prespa under the country's new name - Northern Macedonia - the committee agreed on the possibility of opening accession negotiations with this country in June 2019, assuming the necessary conditions were met.

Potential candidates: Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a potential candidate country. Although it negotiated and signed a Stabilisationagreement and association with the EU in 2008, the entrance entry into force of this agreement remained at Fail mainly due to the country's failure to implement a judgement core topic of the European Court of Human Rights. In the meantime, the Parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina has not reached a agreement concerning the rules of procedure governing its meetings with the European Parliament (twice a year), as these meetings have not been held since November 2015, and this status constitutes a breach of agreement by Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Kosovo is a potential candidate candidate for EU membership. It declared its independence unilaterally in February 2008. All but five Member States (Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia, Spain and Cyprus) have recognised Kosovo's independence. Among the countries in the region, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina have also failed to recognise Kosovo as an independent state. In September 2018, the European Parliament went a step further and decided to open inter-institutional negotiations, which are currently underway. However, the fact that not all member states currently recognise its independence is a major stumbling block.

Negotiating accession: Montenegro and Serbia

Montenegro, one of the smallest states on the European continent, has been part of different empires and states over the past centuries, finally gaining independence peacefully in 2006. It applied to join the Union in December 2008; it was granted the status of a country candidate in December 2010, and accession negotiations started in June 2012. By the end of 2018, 32 negotiating chapters had been opened, out of a total of 35.

Serbia 's process began in December 2009 when former president Boris Tadić officially submitted application for membership and also handed over to justice war criminal Ratko Mladić, manager of the Srebrenica massacre during the Bosnian War, who was hiding on Serbian territory. However, the conflict with Kosovo is one of Serbia's main obstacles to EU accession. It was granted country status candidate in March 2012, after Belgrade and Pristina reached an agreement agreement on Kosovo's regional representation. The official opening of accession negotiations took place on 21 January 2014. In February 2018, the Commission published a new strategy for the Western Balkans stating that Serbia (as well as Montenegro) could join the EU by 2025, while acknowledging the "extremely ambitious" nature of this prospect. Serbia's future EU membership, like that of Kosovo, remains closely linked to the high-level dialogue between Serbia and Kosovo under EU auspices, which should lead to a legally binding comprehensive agreement on the normalisation of their relations.

A step back in the negotiations

In October 2019, a summit was held in Brussels, goal to structure the negotiations of the official candidates for EU membership. Both North Macedonia and Albania were convinced that a date would be set to start the long process of negotiations. However, the process reached a stalemate after seven hours of wrangling, with France rejecting both countries' entrance . France led the campaign against enlargement, but Denmark and the Netherlands also joined the veto. They argue that the EU is not ready to take on new members. "It doesn't work too well at 28, it doesn't work too well at 27, and I'm not sure it will work any better with another enlargement. So we have to be realistic. Before enlarging, we need to reform ourselves," said French President Emmanuel Macron.

The then president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, considered the suspension to be a major historic mistake and hoped that it would only be temporary. For his part, Donald Tusk said he was "ashamed" of the decision, and concluded that North Macedonia and Albania were not to blame for the status created, as the European Commission's reports were clear that both had done what was necessary to start negotiations with the EU.

In Albania, Prime Minister Edi Rama said that the lack of consensus among European leaders would not change Albania's future EU membership aspirations. He asserted that his government was determined to push ahead with the reforms initiated in the electoral, judicial and administrative spheres because it considered them necessary for the country's development , not just because Brussels demanded it.

In North Macedonia, on the other hand, the European rejection was deeply disappointing, as the country had proceeded to reform its institutions and judicial system and fight corruption; it had also changed its constitution, its name and its national identity. The rejection left the country, candidate official status for the past 14 years, in a state of great uncertainty, and Prime Minister Zoran Zaev decided to dissolve parliament and call elections for 12 April 2020 (later postponed due to the Covid-19 emergency). "We have fulfilled our obligations, but the EU has not. We are the victims of a historic mistake that has led to a huge disappointment," Zaev said.

A new, stricter process

Despite the fact that, according to the Commission, North Macedonia and Albania fulfilled the requirements criteria to become accession candidates, Macron proposed to tighten the accession process. In order to unblock status and continue with the process, which the EU claims to be a priority goal , Brussels has given in to the French president's request by establishing a new methodology for integrating new countries.

The new process envisages the possibility of reopening chapters of the negotiations that were considered closed or of fail the talks underway in one of the chapters; it even envisages paralysing the negotiations as a whole. It aims to give more weight to governments and to facilitate the suspension of pre-accession funds or the freezing of the process if candidate countries freeze or reverse committed reforms. The new method will apply to Albania and North Macedonia, whose negotiations with the EU have not yet begun, while Serbia and Montenegro will be able to choose whether to join, without having to change their established negotiating framework , according to the Commission.

Apart from China, Italy has received aid from Russia and Cuba, making a risky geopolitical move in the European context.

The global spreading of the virus is putting under stress the big ally of the Union, the United States, which is demonstrating its lack of an efficient social health care system. Furthermore, the initial refusal of Washington to send help to the EU was seen as an opportunity for countries like Russia, China and Cuba to send medical and technical support to those countries of the EU that are most affected by the virus. Italy has taken aid send by Beijing, Moscow and Havana, shaking the geopolitical understandings of the EU's foreign policy.

![Russia's aid arrived in Italy in the middle of the pandemic crisis [Russian Defense Ministry]. Russia's aid arrived in Italy in the middle of the pandemic crisis [Russian Defense Ministry].](/documents/10174/16849987/coronavirus-italia-blog.jpg)

▲ Russia's aid arrived in Italy in the middle of the pandemic crisis [Russian Defense Ministry].

ARTICLE / Matilde Romito

The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared Corona Virus (Covid-19) a pandemic on the 11th of March, 2020. The fast widespread of the virus pushed numerous countries around the world and especially in Europe where there is the highest number of confirmed cases, to call for a lockdown. This extreme measure is not only leading the EU and the entire world towards an unprecedented economic crisis, but it is also redefining geopolitics and the system of alliances we were used to.

The pandemic. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the first outbreak of novel coronavirus a 'public health emergency of international concern'. In mid-February, numerous cases of corona virus began to be reported in northern Italy and in several European countries. Initially, the spread of the virus mainly hit Italy, which reported the biggest number of cases among the EU states. In March, Italy started with the implementation of social-distancing measures and the consequent lockdown of the country, followed by Spain, France and other European countries. On March 11, 2020, the WHO declared covid-19 a global pandemic. Currently, Europe is the region of the world with the highest number of confirmed cases. According to the WHO, on April 6, Europe reached 621,407 cases compared to the 352,600 cases in America and the 112,524 in Western Asia.

The global lockdown. At first, several major airlines suspended their flights from and to China, in order to avoid further contaminations. Now, the majority of flights in Europe and in other regions have been cancelled. The biggest areas of world are under lockdown and the economic consequences of this are becoming more and more evident. A forced social distancing seems to be the only way to contain the spread of the virus and the closing of national borders is currently at the center of states' policies to combat the virus. However, some European countries, such as Sweden, do not seem to agree on this.

Lack of solidarity

We are assisting to a global situation of 'everybody for oneself,' and this has become highly evident within the EU itself. Individual countries within the Union have shown high levels of egoism on different occasions. The North-South divide within the EU is clearer than ever, particularly between the Netherlands and Austria on the one side, and Italy, Spain, France and Greece on the other side. The former group of countries is asking for compromise and conditions to lend money to the most afflicted ones for countering the crisis, while the latter group is asking the EU to share the debts accumulated in order to save European economies (eurobonds).

The different spread-intensity of the virus in different European countries has shown more than once the fragility of the Union, which demonstrated to be led by the arrogance of the rich. On different occasions European leaders have shown a lack of European identity, solidarity and common vision. For instance, at the beginning of the crisis France and Germany attempted to 'cover with the European flag' medical products directed to Italy, by declaring them 'European products', trying to compensate the initial inaction of the EU. Another example, could be the seizure by the Czech Republic of 110,000 Chinese masks and thousands of breathing supports, which were destined to Italy (March the 21st). Moreover, the lack of unity also came from an unjustified action of protectionism undertaken by Poland, which closed its market to agricultural products coming from Italy on March 18, despite it was already known that the virus could not be spread through such products.

Nevertheless, there are some good and unexpected examples of solidarity. For instance, a good lesson on European solidarity came from the small state of Albania. The Albanian prime minister Edi Rama taught European leaders what it means to be part of the EU by sending a medical unit to the Italian region of Lombardy, despite the numerous difficulties Albania is facing, thus showing that the fight against the virus has no nationality and it cannot leave room for egoistic calculations. Moreover, more recently Germany has accepted to receive and take care of numerous patients coming from Italy, where the majority of health infrastructures are saturated.

Overall, little comprehension and solidarity has been shown between European member states, thus being criticised by the European Commission president, Ursula Von Der Leyen.

Geopolitical tensions

The EU is going through numerous changes in the relations between its members. The closing up of individual countries poses a big challenge to the EU itself, which is founded on freedom of movement of people and goods.

Currently, sending masks and medicines seems to have become the main means for countries to exert influence in global affairs. The global spreading of the virus is putting under stress the big ally of the Union, the United States (US), which is demonstrating its lack of an efficient social health care system. Furthermore, the initial refusal of Washington to send help to the EU was seen as an opportunity for countries like Russia, China and Cuba to send medical and technical support to those countries of the EU that are most affected by the virus, like Italy and Spain. After having seen its hegemonic position in Europe under threat, the US decided to send monetary help to some European countries, such as 100 million dollars to Italy, in order to help in countering the emergency.

At the end, the EU seems to start standing all together. But, did the European countries take action on time? Generally, countries, like human beings, are more likely to remember one bad impression better than numerous good ones. Therefore, are countries like Italy going to 'forgive' the EU and its initial inactivity? Or are they going to fall back on countries like Russia and China, which have shown their solidarity since the beginning?

Furthermore, did the EU take action because of an inherent identity and solidarity? Or was it just a counteraction to the Chinese and Russian help? It seemed that specifically Germany's mobilisation followed the exhortation of the former president of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi. He accused Germany and other countries of taking advantage of the virus for imposing a 'conditionality' to the countries that were asking for help. Moreover, in an interview on the Financial Times he called for an exceptional investment in the economies and for a guarantee of the debts, in order to jointly face the crisis, because no country can face this unprecedented threat alone. Now, anti-virus economic action turned into a matter of urgency for Europe and the European Commission is working on a common European response to the crisis.

Future perspectives

Probably, after the end of the virus spread, the world will assist to important changes in the global dynamics of alliances. Russia and China will most likely have one or more European allies to advance their interests in the EU. On the one side, this could lead to a further weakening of the EU governance and to the re-emergence of nationalism on states' behaviour within the Union. And on the other side, it could lead to the development of further mechanisms of cooperation among the EU members, which will go beyond the eurobonds and will probably extend to the sanitary dimension.

To preserve its unity, the European political-economic-cultural area will need to be strengthened, by fighting inequalities with a new model of solidarity. Its future prosperity will most likely depend on its internal market.

Nevertheless, for now the only thing we can be sure about is that the first impression on the EU was very bad and that this situation is going to lead all of us towards an unprecedented economic crisis, which most probably will redefine the political relationships between the world's biggest regions.

![staff UNHCR staff building a tent for Venezuelan refugees in the Colombian city of Cúcuta [UNHCR]. staff UNHCR staff building a tent for Venezuelan refugees in the Colombian city of Cúcuta [UNHCR].](/documents/10174/16849987/acnur-blog.jpg)

staff UNHCR building a tent for Venezuelan refugees in the Colombian city of Cúcuta [UNHCR].

COMMENTARY / Paula Ulibarrena

Restrictive measures imposed by states to try to contain the coronavirus epidemic mean that millions of people are no longer able to go to work or work from home. But not everyone can stop working or switch to teleworking. There are self-employed people, small businesses, neighbourhood shops, street traders or street vendors, and freelance artists who live practically from day to day. For them, and for many others who have no or reduced income, expenses will continue to mount: utility bills, rents, mortgages, school fees and, of course, food and medicine.

All these social impacts of the coronavirus crisis are already beginning to be questioned by those living in the "red zone" of the epidemic. In Italy, for example, some political groups have demanded that aid should not go to large companies, but to this group of precarious workers or needy families, and are demanding a "basic quarantine income".

Similar approaches are emerging in other parts of the world and have even led some leaders to anticipate the demands of the population. In France, Emmanuel Macron announced that the government will take over the loans, and suspended the payment of rents, taxes and electricity, gas and water bills. In the United States, Donald Trump's government announced that cheques will be sent to each family to cover the costs or risks involved in the pandemic.

In other major crises the state has come to the rescue of large companies and banks. Now there are calls for public resources to be devoted to rescuing those most in need.

In any crisis, it is the most disadvantaged who suffer the most. Today, there are more than 126 million people in the world in need of humanitarian assistance, including 70 million forcibly displaced people. attendance . Within these groups, we are beginning to see the first cases of infection (Ninive-Iraq IDP camp, Somalia, Afghanistan, Nigeria, Sudan, Venezuela report ), the cases in Burkina Faso are particularly illustrative of the challenge of responding in a context where medical care is limited. Malian refugees who were once displaced to Burkina Faso are being forced to return to Mali, and ongoing violence inhibits humanitarian and medical access to affected populations.

Many refugee camps suffer from inadequate hygiene and sanitation facilities, creating conditions conducive to the spread of disease. Official response plans in the US, South Korea, China and Europe require social distancing, which is physically impossible in many IDP camps and in the crowded urban contexts in which many forcibly displaced people live. Jan Egeland, director general of the Norwegian Refugee Agency committee , warned that COVID-19 could "decimate refugee communities".

Jacob Kurtzer of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington warns that national policies of isolation in reaction to the spread of COVID-19 also have negative consequences for people facing humanitarian emergencies. Thus the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration have announced the end of refugee resettlement programmes, as some host governments have halted refugee entrance and imposed travel restrictions as part of their official response.

Compounding these challenges is the reality that humanitarian funding, which can barely meet global demand, may be affected as donor states feel they must focus such funds on the Covid-19 response at this time.

On the other side of the coin, the coronavirus could provide an opportunity to de-escalate some armed conflicts. For example, the EU has order ceased hostilities and stopped military transfers in Libya to allow authorities to focus on responding to the health emergency. The Islamic State has posted repeated messages on its Al-Naba information bulletin calling on fighters not to travel to Europe and to reduce attacks while concentrating on staying free of the virus.

Kurtzer suggests that this is an opportunity to reflect on the nature of humanitarian work abroad and ensure that it is not overlooked. Interestingly, developed countries face real medical vulnerability, indeed Médecins Sans Frontières has opened facilities in four locations in Italy. Cooperating with trusted humanitarian organisations at the national level will be vital to respond to the needs of the population and at the same time develop a greater understanding of the vital work they perform in humanitarian settings abroad.

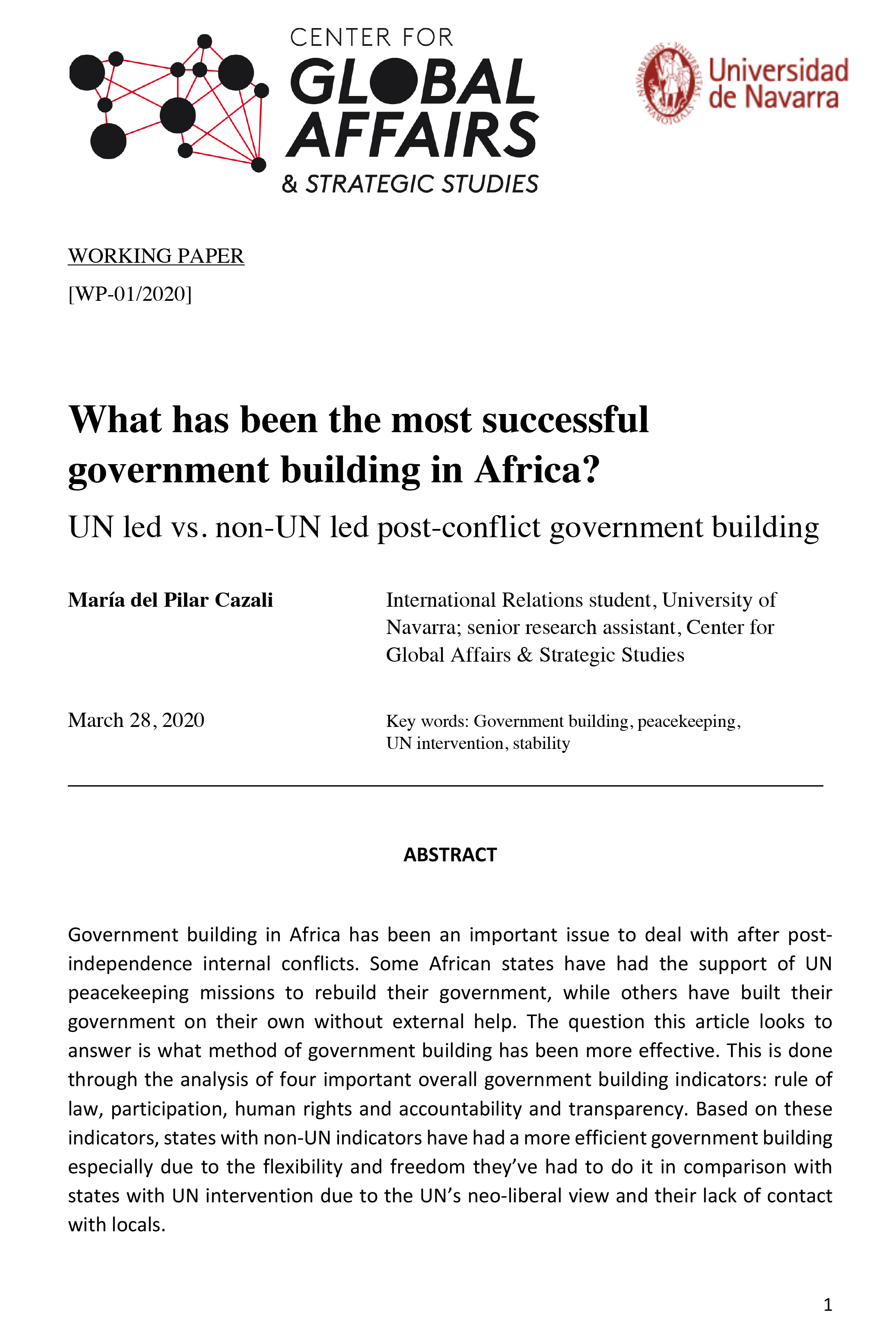

UN led vs. non-UN led post-conflict government building

WORKING PAPER / María del Pilar Cazali

ABSTRACT

Government building in Africa has been an important issue to deal with after post- independence internal conflicts. Some African states have had the support of UN peacekeeping missions to rebuild their government, while others have built their government on their own without external help. The question this article looks to answer is what method of government building has been more effective. This is done through the analysis of four important overall government building indicators: rule of law, participation, human rights and accountability and transparency. Based on these indicators, states with non-UN indicators have had a more efficient government building especially due to the flexibility and freedom they've had to do it in comparison with states with UN intervention due to the UN's neo-liberal view and their lack of contact with locals.

Download the document [pdf. 431K]

Download the document [pdf. 431K]

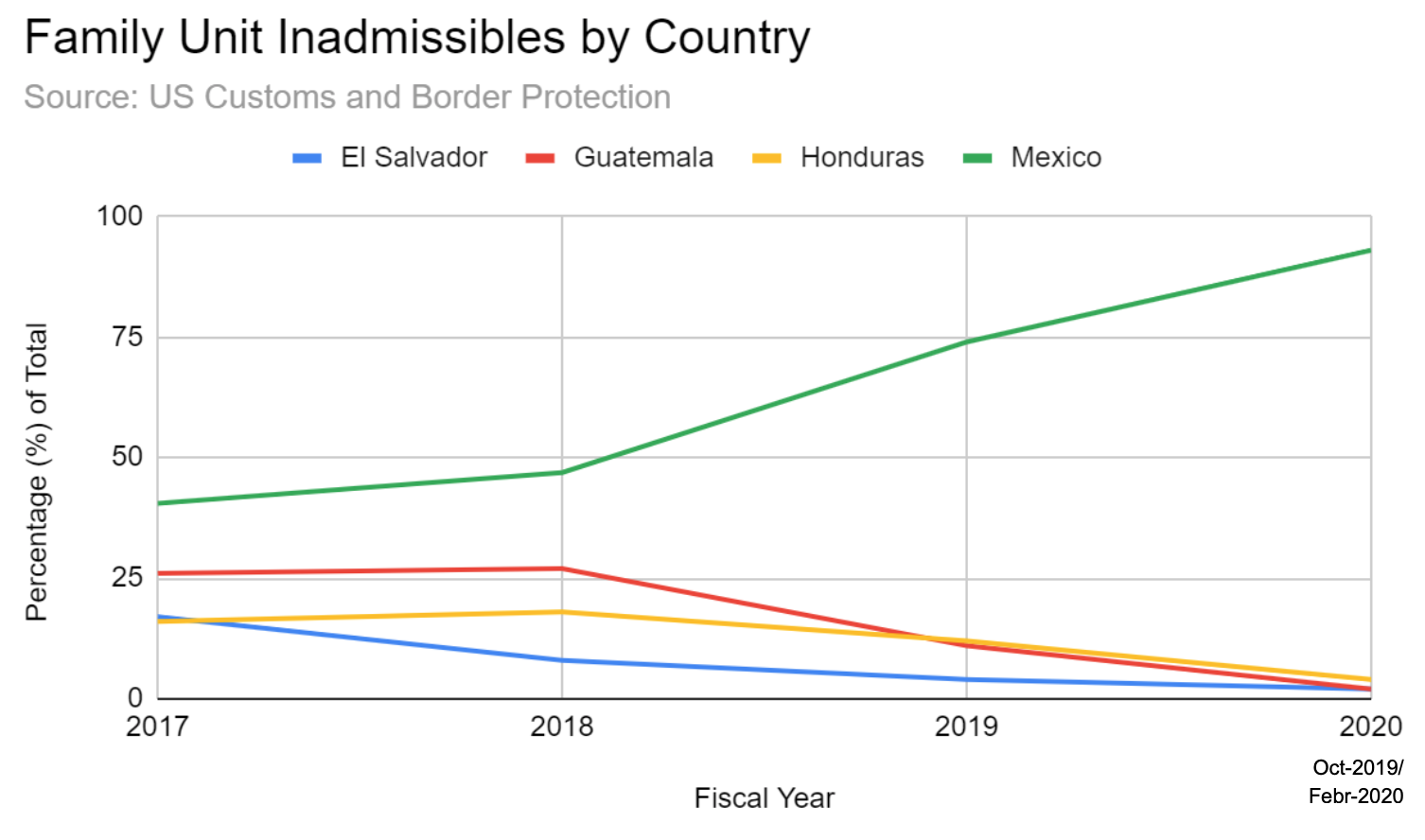

The Trump Administration's Newest Migration Policies and Shifting Immigrant Demographics in the USA

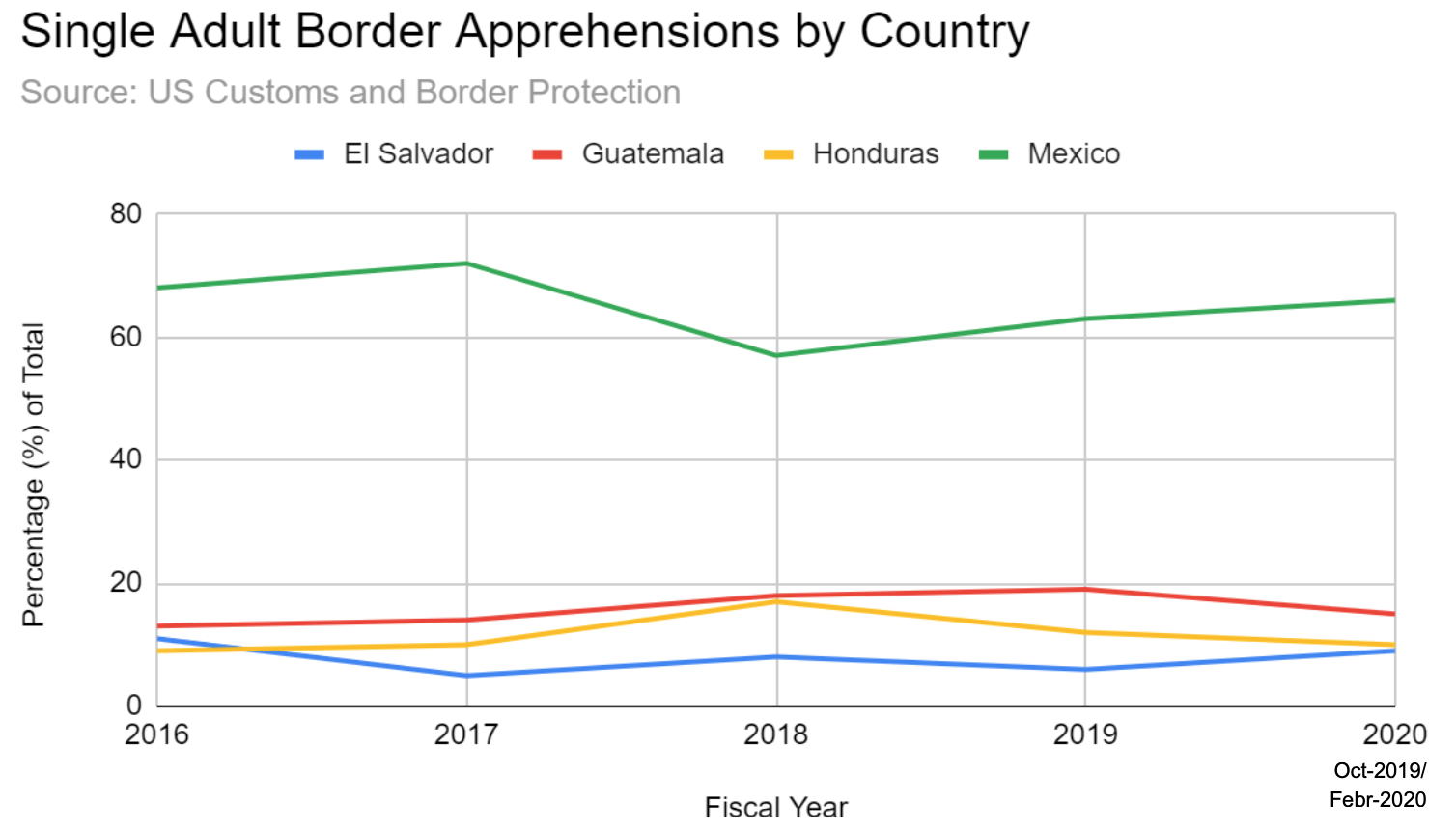

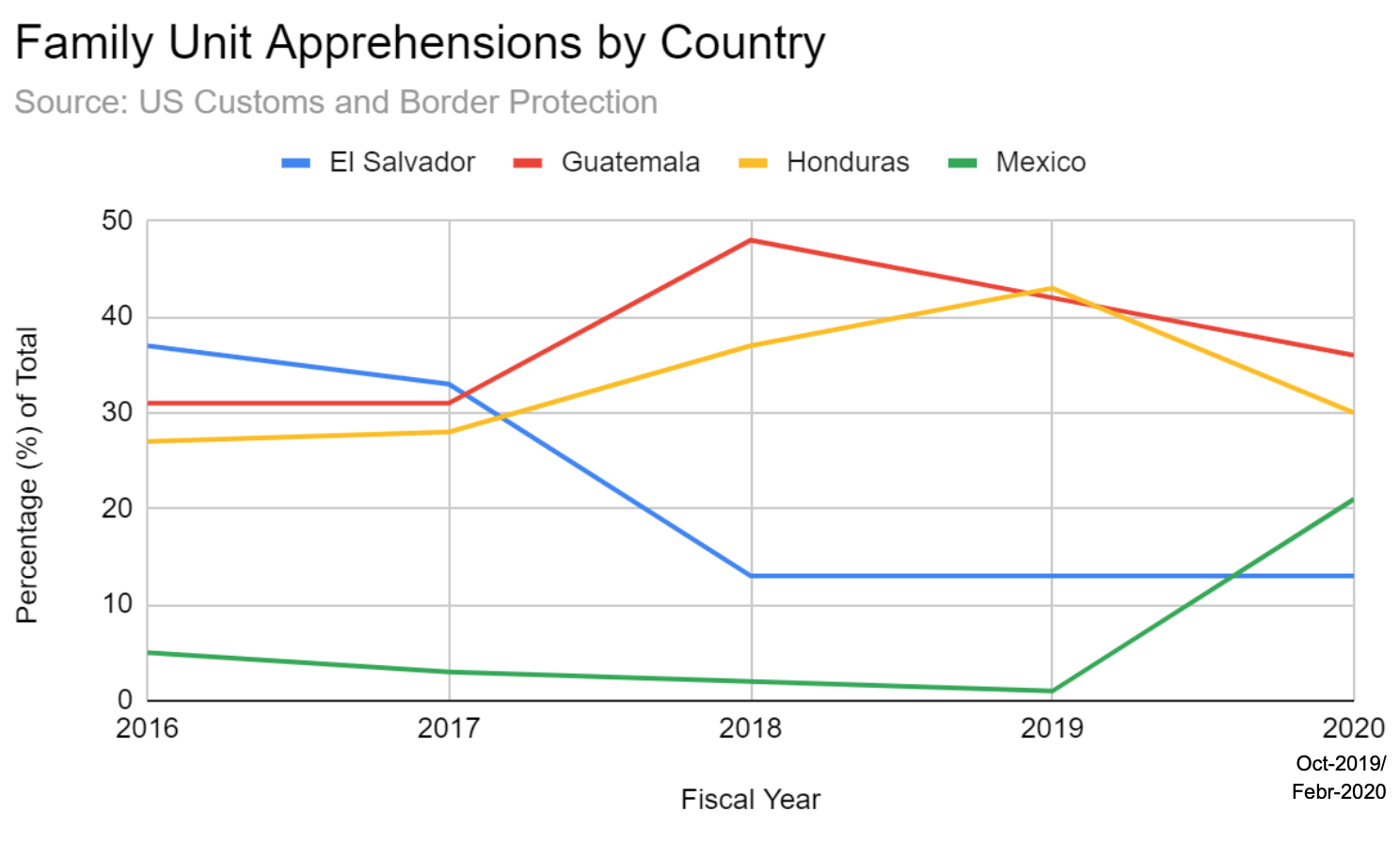

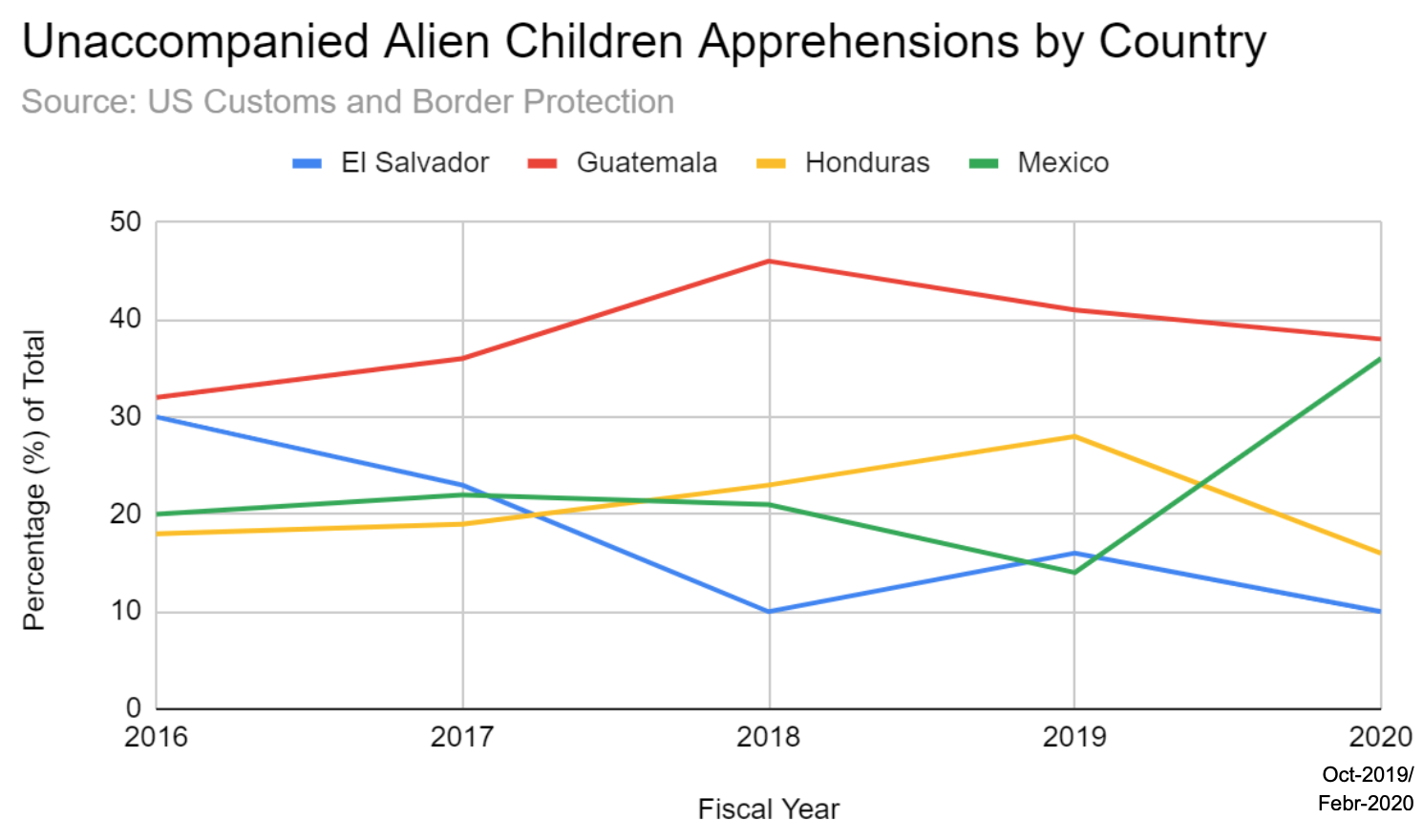

New Trump administration migration policies including the "Safe Third Country" agreements signed by the USA, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras have reduced the number of migrants from the Northern Triangle countries at the southwest US border. As a consequence of this phenomenon and other factors, Mexicans have become once again the main national group of people deemed inadmissible for asylum or apprehended by the US Customs and Border Protection.

![An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov]. An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov].](/documents/10174/16849987/migracion-mex-blog.jpg)

▲ An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov].

ARTICLE / Alexandria Casarano Christofellis

On March 31, 2018, the Trump administration cut off aid to the Northern Triangle countries in order to coerce them into implementing new policies to curb illegal migration to the United States. El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala all rely heavily on USAid, and had received 118, 181, and 257 million USD in USAid respectively in the 2017 fiscal year.

The US resumed financial aid to the Northern Triangle countries on October 17 of 2019, in the context of the establishment of bilateral negotiations of Safe Third Country agreements with each of the countries, and the implementation of the US Supreme Court's de facto asylum ban on September 11 of 2019. The Safe Third Country agreements will allow the US to 'return' asylum seekers to the countries which they traveled through on their way to the US border (provided that the asylum seekers are not returned to their home countries). The US Supreme Court's asylum ban similarly requires refugees to apply for and be denied asylum in each of the countries which they pass through before arriving at the US border to apply for asylum. This means that Honduran and Salvadoran refugees would need to apply for and be denied asylum in both Guatemala and Mexico before applying for asylum in the US, and Guatemalan refugees would need to apply for and be denied asylum in Mexico before applying for asylum in the US. This also means that refugees fleeing one of the Northern Triangle countries can be returned to another Northern Triangle country suffering many of the same issues they were fleeing in the first place.

Combined with the Trump administration's longer-standing "metering" or "Remain in Mexico" policy (Migrant Protection Protocols/MPP), these political developments serve to effectively "push back" the US border. The "Remain in Mexico" policy requires US asylum seekers from Latin America to remain on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border to wait their turn to be accepted into US territory. Within the past year, the US government has planted significant obstacles in the way of the path of Central American refugees to US asylum, and for better or worse has shifted the burden of the Central American refugee crisis to Mexico and the Central American countries themselves, which are ill-prepared to handle the influx, even in the light of resumed US foreign aid. The new arrangements resemble the EU's refugee deal with Turkey.

These policy changes are coupled with a shift in US immigration demographics. In August of 2019, Mexico reclaimed its position as the single largest source of unauthorised immigration to the US, having been temporarily surpassed by Guatemala and Honduras in 2018.

US Customs and Border Protection data indicates a net increase of 21% in the number of Unaccompanied Alien Children from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador deemed inadmissible for asylum at the Southwest US Border by the US field office between fiscal year 2019 (through February) and fiscal year 2020 (through February). All other inadmissible groups (Family Units, Single Adults, etc.) experienced a net decrease of 18-24% over the same time period. For both the entirety of fiscal year 2019 and fiscal year 2020 through February, Mexicans accounted for 69 and 61% of Unaccompanied Alien Children Inadmissible at the Southwest US border respectively, whereas previously in fiscal years 2017 and 2018 Mexicans accounted for only 21 and 26% of these same figures, respectively. The percentages of Family Unit Inadmisibles from the Northern Triangle countries have been decreasing since 2018, while the percentage of Family Unit Inadmisibles from Mexico since 2018 has been on the rise.

With asylum made far less accessible to Central Americans in the wake of the Trump administration's new migration policies, the number of Central American inadmisibles is in sharp decline. Conversely, the number of Mexican inadmisibles is on the rise, having nearly tripled over the past three years.

Chain migration factors at play in Mexico may be contributing to this demographic shift. On September 10, 2019, prominent Mexican newspaper El discussion published an article titled "Immigrants Can Avoid Deportation with these Five Documents." Additionally, The Washington Post cites the testimony of a city official from Michoacan, Mexico, claiming that a local Mexican travel company has begun running a weekly "door-to-door" service line to several US border points of entry, and that hundreds of Mexican citizens have been coming to the municipal offices daily requesting documentation to help them apply for asylum in the US. Word of mouth, press coverage like that found in El discussion, and the commercial exploitation of the Mexican migrant situation have perhaps made migration, and especially the claiming of asylum, more accessible to the Mexican population.

US Customs and Border Protection data also indicates that total apprehensions of migrants from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador attempting illegal crossings at the Southwest US border declined 44% for Unaccompanied Alien Children and 73% for Family Units between fiscal year 2019 (through February) and fiscal year 2020 (through February), while increasing for Single Adults by 4%. The same data trends show that while Mexicans have consistently accounted for the overwhelming majority of Single Adult Apprehensions since 2016, Family Unit and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions until the past year were dominated by Central Americans. However, in fiscal year 2020-February, the percentages of Central American Family Unit and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions have declined while the Mexican percentage has increased significantly. This could be attributed to the Northern Triangle countries' and especially Mexico's recent crackdown on the flow of illegal immigration within their own states in response to the same US sanctions and suspension of USAid which led to the Safe Third Country bilateral agreements with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

While the Trump administration's crackdown on immigration from the Northern Triangle countries has effectively worked to limit both the legal and illegal access of Central Americans to US entry, the Trump administration's crackdown on immigration from Mexico in the past few years has focused on arresting and deporting illegal Mexican immigrants already living and working within the US borders. Between 2017 and 2018, ICE increased workplace raids to arrest undocumented immigrants by over 400% according to The Independent in the UK. The trend seemed to continue into 2019. President Trump tweeted on June 17, 2019 that "Next week ICE will begin the process of removing the millions of illegal aliens who have illicitly found their way into the United States. They will be removed as fast as they come in." More deportations could be leading to more attempts at reentry, increasing Mexican migration to the US, and more Mexican Single Adult apprehensions at the Southwest border. The Washington Post alleges that the majority of the Mexican single adults apprehended at the border are previous deportees trying to reenter the country.

Lastly, the steadily increasing violence within the state of Mexico should not be overlooked as a cause for continued migration. Within the past year, violence between the various Mexican cartels has intensified, and murder rates have continued to rise. While the increase in violence alone is not intense enough to solely account for the spike that has recently been seen in Mexican migration to the US, internal violence nethertheless remains an important factor in the Mexican migrant situation. Similarly, widespread poverty in Mexico, recently worsened by a decline in foreign investment in the light of threatened tariffs from the USA, also plays a key role.

In conclusion, the Trump administration's new migration policies mark an intensification of long-standing nativist tendencies in the US, and pose a potential threat to the human rights of asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border. The corresponding present demographic shift back to Mexican predominance in US immigration is driven not only by the Trump administration's new migration policies, but also by many other diverse factors within both Mexico and the US, from press coverage to increased deportations to long-standing cartel violence and poverty. In the face of these recent developments, one thing remains clear: the situation south of the Rio Grande is just as complex, nuanced, and constantly evolving as is the situation to the north on Capitol Hill in the USA.

▲ A picture of Vladimir Putin on Sputnik's website

ESSAY / Pablo Arbuniés

A new form of power

Russia's growing influence in African countries and public opinion has often been overlooked by western democracies, giving the Kremlin a lot of valuable time to extend its influence on the continent.

Until very recently, western democracies have looked at influence efforts from authoritarian countries as nothing more than an exercise of soft power. Joseph S. Nye defined soft power as a nation's power of attraction, in contrast to the hard power of coercion inherent in military or economic strength (Nye 1990). However, this influence does not fit the common definition of soft power as 'winning hearts and minds'. In the last years China and Russia have developed and perfected extremely sophisticated strategies of manipulation aimed towards the civilian population of target countries, and in the case of Russia the role of Russia Today should be taken as an example.

These strategies go beyond soft power and have already proved their effectiveness. They are what the academia has recently labelled as sharp power (Walker 2019). Sharp power aims to hijack public opinion through disinformation or distraction, being an international projection of how authoritarian countries manipulate their own population (Singh 2018).

Sharp power strategies are being severely underestimated by western policy makers and advisors, who tend to focus on more classical conceptions of the exercise of power. As an example, the "Framework document" issued by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies on Russia-Africa relations (Mora Tebas 2019). The document completely ignores sharp power, labelling Russian interest in communication markets as no more than regular soft power without taking into consideration the disinformative and manipulative nature of these actions.

A growing interest in Africa

Over the past 20 years, many international actors have shifted their interest towards the African continent, each in a different way.

China has made Africa a major geopolitical target in recent years, focusing on economic investments for infrastructure development. Such investments can be noticed in the Ethiopian dam projects such as the Gibe III, or in the Entebbe-Kampala Expressway in Uganda.

This could be considered as debt-trap diplomacy, as China uses infrastructure investments and development loans to gain leverage over African countries. However, there is also a key geopolitical interest, especially in those countries with access to the network Sea and the Indian Ocean, due to the One Belt One Road Initiative. This project requires a net of seaports, where Kenya, and specifically the port of Lamu, could play a key role in becoming a hub for trade in East Africa (Hurley, Morris and Portelance 2019).

Also, Chinese investments are attractive for African countries because they do not come with prerequisites of democratisation or transparent administration, unlike those from western countries.

Yet, even though both China and Russia use sharp power as part of their foreign policy strategies, China does barely use it in Africa, since its interests in the continent are more economic than political. This is based on the view that China is more keen to exploit Africa's natural resources (Mlambo, Kushamba and Simawu 2016) than anything else.

On the other hand, Russia has both economic and military interests in the region. This is exemplified by the case of Sudan, where in addition to the economic interest in natural resources, there is also a military interest in accessing the network Sea. In order to achieve these goals, the first step is to grant stability in the country, and it can be achieved through ensuring that public opinion supports the government and accepts Russian presence.

The idea of a Russian world-Russkiy spanish medical residency program-has grown under Putin and is key to understanding the country's soft and sharp power strategies. It consists on the expansion of power and culture using any means possible in order to regain the lost superpower status.

However, this approach must not be seen only as a nostalgic push to regain status, but also from a purely pragmatic point of view, since economic and practical factors have "pushed aside ideology" in the competition against the West (Warsaw Institute 2019).

The recent Russia-Africa Summit (23-24 October 2019), that took place in Sochi, Russia, proves how Russia has pivoted towards Africa in recent years, offering infrastructure, energy and other investments as well as arms deals and different advisors. The outcome of this pivoting is being quite beneficial for Moscow in strategic terms.

The Kremlin's interest in Africa was not remarkable until the post Crimea invasion. The economic sanctions imposed after the occupation of Crimea forced Russia to look further abroad for allies and business opportunities. For instance, as part of this policy there was a more robust involvement of Russia in Syria.

The Russian strategy for the African continent involves benefiting favourable politicians through political and military advisors and offering control on average influence (Warsaw Institute 2019). In exchange, Russia looks for military and energy supply contracts, mining concessions and infrastructure building deals. Moreover, on a bigger picture, Russia-as well as China-aims to reduce the influence of the US and former colonial powers France and the UK.

Leaked documents published by The Guardian (Harding and Buerke 2019), show this effort to gain influence on the continent, as well as the strategies followed and the degree of cooperation with the different powers-from governments to opposition groups or social movements.

However, the growth of Russia's influence in Africa cannot be understood without the figure of Yevgeny Prigozhin, an extremely powerful oligarch which, according to US special counsel Robert Mueller, was critical to the social average campaign for the election of Donald Trump in 2016. He is also linked to the foundation of the Wagner group, a private military contractor present among other conflicts in the Syrian war.

Prigozhin, through a network of enterprises known as 'The Company' has been for long the head of Putin's plans for the African continent, being responsible of the growing number of Russian military experts involved with different governments along the continent, and now suspected to lead the push to infiltrate in the communication markets.

Between 100 and 200 spin doctors have already been sent to the continent, reaching at least 10 different countries (Warsaw Institute 2019). Their focus is on political marketing and especially on social average, with the hope that it can be as influential as in the Arab Springs.

Main targets

Influence in the average is one of the key aspects of Russia's influence in Africa, and the main targets in this aspect are the Central African Republic, Madagascar, South Africa and Sudan. Each of these countries has a potential for Russian interests, and is targeted on different levels of cooperation, from weapons deals to spin doctors (Warsaw Institute 2019), but all of them are targets for sharp power strategies.

However, it is hard for a foreign government to directly enter the communication markets of another country without making people suspicious of its activities, and that is where The Company plays its role. Through it, pro-Russian publishing house lines are fed to the population of the target states by acquiring already existing average platforms-such as newspapers or television and radio stations-or creating new ones directly under the supervision of officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, this ensures that the dominant frames fit Russia's interests and that of its allies.