The country left the cartel in order to expand pumping, but the Covid-19 crisis has cut extraction volumes by 10.8%.

Construction of a variant of the oil pipeline that crosses the Andes, from the Ecuadorian Amazon to the Pacific [Petroecuador].

ANALYSIS / Jack Acrich and Alejandro Haro

Ecuador left the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) on 1 January 2020 to avoid having to continue to join the production cuts imposed by group , which it agrees to in order to push up the world price of crude oil. Ecuador preferred to sell more barrels, albeit at a lower price, because by exporting more at the end of the day written request it could increase its income and thus get out of its serious financial situation status , which the coronavirus emergency has only accentuated, with a fall in GDP in 2020 currently estimated at 9.5 per cent.

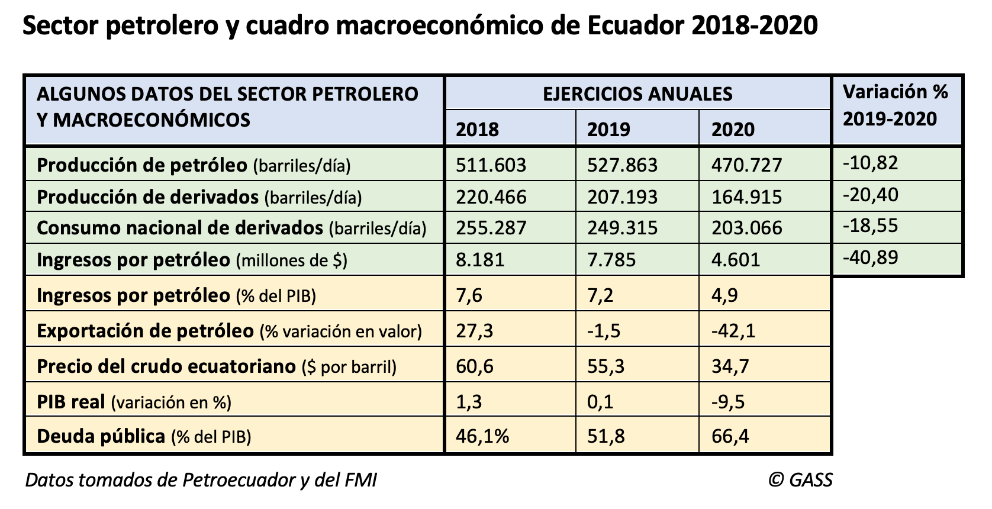

However, domestic economic difficulties and the difficult international situation have not only prevented Ecuador from expanding pumping, but oil production has fallen by 10.8% in the last year. average In 2020, Ecuador extracted 472,000 barrels of oil per day, especially affected by the sharp reduction in activity in April with the beginning of the confinement, which was not compensated for the rest of the year. agreement This is a volume that is below the 500,000 line that has always been exceeded in recent years (in 2019 production was 528,000), according to figures from Petroecuador, the state hydrocarbons company. The reduction in global consumption during the Covid-19 year also correlated with a drop in the consumption of derivatives in Ecuador, especially gasoline and diesel, which fell by 18.5%.

International investment constrained by the pandemic context and reduced consumption marked a status that could hardly lead to an increase in production. In 2020, Ecuador saw a drop in the value of oil exports of 42.1% (twice as much as total exports), which, combined with a deterioration in the price of a barrel of oil, meant a 40.9% reduction in public revenue from the oil sector, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) data .

The figures for the first two months of 2021 indicate an accentuation of the fall in crude oil production (-4.73% compared to January and February 2020) and derivatives (-7.47%), as well as their export (-22.8%).

Cutting expense and seeking oil revenues

Exiting OPEC did not pose any particular risk for Ecuador, which had already left the organisation in a previous period. Its limited weight in OPEC and the progressive decline in the cartel's own strength meant that Ecuador's attempt to go it alone was not particularly costly. The absolute priority of Lenín Moreno's government was to rebalance the country's macroeconomic picture - battered by the high public expense of his predecessor, Rafael Correa - and for this it urgently needed to increase state revenue, a significant part of which in Ecuador normally comes from the hydrocarbons sector.

When he became president in 2017, Moreno set out to steer the country towards more market-friendly energy policies. The president was determined to break with the nationalist approach of his predecessor, whose policies discouraged foreign investment in the oil industry while significantly increasing public debt. Among the most costly programmes undertaken by Correa was to maintain high subsidies for energy consumption, with especially low fuel prices.

In order to overcome the financial status that Ecuador found itself in when he took office, Moreno approached the IMF to apply for financial aid financial, and committed to structural reforms, including the gradual dismantling of subsidies. These reforms, however, were not well received and the social unrest that spread throughout the country put further pressure on the oil industry.

In February 2019, Moreno negotiated an IMF loan to help reduce the country's large fiscal deficit and huge external debt, which by the end of 2018 had reached 46.1 per cent of GDP and twelve months later would reach 51.8 per cent. The committed 'bailout' was for $10.2 billion, of which $6.5 billion came from the IMF and the rest from other international agencies.

As part of austerity measures agreed with the IMF, Moreno was forced to end government subsidies that had kept petrol prices low for decades. In early October 2019 he announced a plan of cuts to save $2.27 billion a year, essentially withdrawing the fuel subsidy. The advertisement decree, which would later be annulled, immediately provoked massive protests, both from transporters and low-income sectors, as well as most notably from indigenous communities. The street violence forced the president to leave Quito for a few days and move to Guayaquil.

To address the need for revenue, Moreno sought to rely on the oil industry, which accounts for roughly a third of the country's total exports. He initially expressed the intention to seek a rise from the 545,000 barrels of crude oil produced at the time to almost 700,000 barrels a day.

goal One of the measures taken in this direction was to promote the development and the exploitation of the Ishpingo-Tiputini-Tambococha field, with the aim of increasing oil production by 90,000 barrels a day. This decision met with social rejection due to the environmental damage it could cause, as the Yasuní National Park, in the Ecuadorian Amazon, has been declared a protected area. The government then decided to postpone the expansion of production, first to 2021 and then to 2022. The civil service examination was especially led by indigenous communities, in a mobilisation that partly explains the success in the 2021 presidential elections of Yaku Pérez's indigenist Pachakutik movement, which almost made it to the second round.

Another measure was to reverse some of his predecessor's emblematic policies. For example, he eliminated the service contracts introduced under President Correa, thus restoring the model production-sharing contract. This reform was more favourable to international oil companies, as it allowed them to retain a share of oil reserves; it also offered them financial incentives to invest in the country. The new model was first applied in the tenders awarded during the twelfth Intracampos oil round, in the Oriente region, which is rich in oil reserves. Under this contract modality , the Moreno administration awarded seven of the eight exploration blocks on offer with a total investment of more than $1.17 billion.

Fall in production

Due to the urgency of increasing revenues, Ecuador resisted the plan of production cuts that OPEC has been imposing on its members at various times since the abrupt fall in oil prices in 2014. Initially, the organisation accepted that some of its members, with moderate or very low production volumes compared to previous figures, as was the case of Venezuela, would maintain their extraction rates. But since it could no longer be an exception, Ecuador preferred to announce at the end of 2019 that it would leave OPEC and not have to reduce its production to 508,000 barrels per day in 2020, which was the quota set for it.

What is striking is that last year production finally fell from 528,000 barrels per day in 2019 to 472,000 (a drop of 10.8%), and not because of decisions taken at OPEC headquarters in Vienna but because of the various difficulties subject caused by the Covid-19 crisis. Petroecuador's oil exports fell from 331,321 barrels per day in 2019 to 316,000, a drop of 4.6%, which in monetary terms was greater, as the price of a barrel of Ecuadorian mixed oil fell from 55.3 dollars in 2019 to 34.7 in 2020.

One element that makes it difficult for Ecuador to take better advantage of its hydrocarbon potential is that it has insufficient infrastructure for refining crude oil. The country has three refineries, but their capacity does not reach the volume of domestic consumption of oil derivatives, which means that it must import diesel, naphtha and other products. This means that in times of high oil prices, Ecuador benefits from exports, but also has to pay a higher invoice price for imports of derivatives. In 2020, Petroecuador had to import 137,300 barrels per day.

The complicated situation caused by the pandemic has continued to put pressure on Ecuador's public debt, which reached 66.4% at the end of 2020, despite all the attempts made by the Moreno government to reduce it.

The next president, due to take office at the end of May 2021, will also have little room for manoeuvre due to these debt volumes and will have to continue to rely on higher oil revenues to balance public finances. The expansionary policies of expense during Correa's presidency took place in the context of the commodity super-cycle, which benefited South America so much, but this is unlikely to be repeated in the short term deadline.

OPEC's loss of weight

With its departure from OPEC, Ecuador left an international organisation that was created in 1960 with the aim of regulating the world oil market and controlling oil prices to a certain extent. goal . The founding members were Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. Over time, other countries joined OPEC and today it is made up of thirteen members: Algeria, Angola, Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Libya, Nigeria, United Arab Emirates and the five founding countries. When it was created, the organisation sought to establish, acting as a cartel, a kind of counterweight to a series of Western energy transnationals, mainly from the United States and the United Kingdom. OPEC members account for about 40 per cent of world oil production and contain about 80 per cent of the world's proven oil reserves. To be admitted as a member of the organisation it is necessary to have substantial oil exports and to share those of the member countries.

Ecuador joined OPEC in 1973, but suspended its membership in 1992. Subsequently, in 2007 it resumed active participation until its leave in January 2020. Considering that Ecuador was one of OPEC's smaller members, it did not really have much influence in the organisation and its exit does not represent a substantial loss for the organisation. However, it is a second departure in just one year, as Qatar, which had more weight in the cartel, left on 1 January 2019. In its case, its divorce from OPEC was due to other reasons, such as its tensions with Saudi Arabia and its desire to focus on the gas sector, of which it is one of the world's largest producers.

These moves are an example of OPEC's loss of influence. This has led it to establish alliances with producers that are not part of the organisation, such as Russia and some other countries forming OPEC+. With the decline of oil production in Venezuela and the decreasing ability of other members to control their production and exports, Saudi Arabia has been increasingly consolidating its position as the cartel's leader, accounting for around a third of the total production, with approximately 9.4 million barrels per day. In a way, Saudi Arabia and Russia remain, in a head to head battle, as the main countries seeking to cut production in an attempt to increase prices. Additionally, thanks to fracking, the United States has become the largest oil producer, representing a major influence on the international crude oil market, affecting the power that OPEC may have.