Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs North America .

[Juan Tovar Ruiz, La doctrina en la política exterior de Estados Unidos: De Truman a Trump ( Madrid: Catarata, 2017) 224 pages].

review / Xabier Ramos Garzón

Every change in the White House leads to an analysis of the outgoing president's policies and speculation about the incoming president's policies. Given the weight of the United States in the world, each administration's vision of international affairs is decisive for the world order. Juan Tovar Ruiz, professor of International Office at the University of Burgos, deals in this book with the essence of each president's foreign policy - mainly from Truman to Trump (Biden's, logically, has yet to be defined) - which in many cases follows a defined roadmap that has come to be called 'doctrine'.

The book's strengths include the fact that it combines several points of view: on the one hand, it covers, from a realist point of view, the structural and internal effects of each policy, and on the other hand, it analyses the ideas and interactions between actors from a constructivist point of view. The author explores decision-making processes and their consequences, considers the ultimate effectiveness of American doctrines in the general context of International Office, and examines the influences, ruptures and continuities between different doctrines over time. Despite the relatively short history of the United States, the country has had an extensive and complex foreign policy, which Tovar, focusing on the last eight decades, synthesises with particular merit, adopting a mainly general viewpoint that highlights the substantive.

The book is divided into seven chapters, organised by historical stages and, within each, by presidents. The first chapter, by way of introduction, covers the period following US independence until the end of World War II. This period is sample as a background core topic in future American ideology, with two particularly decisive positions: the Monroe Doctrine and Wilsonian Idealism. The second chapter deals with the First Cold War, with the Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson doctrines. The chapter contextualises the various postulates and identifies the issues that went to core topic in the creation of doctrines that only affected the foreign policy of the time, but became embedded in the core of American political thought. The third chapter deals with the Distension, the period between 1969 and 1979 in which the Nixon and Carter doctrines came into being. The fourth chapter takes us to the Second Cold War and the end of the US-USSR confrontation, a time when we find the doctrines of Reagan and Bush senior. From this point, the following chapters (fifth, sixth and seventh) deal with the post-Cold War period, with the doctrines of Clinton, Bush junior and the more recent - and therefore still subject to study - doctrines of Obama and Trump.

In the conclusions, the author summarises each of the chapters on the basis of academic or political characterisations and makes some qualifications, such as warning that in his opinion Obama's foreign policy is more of a "non-doctrine", as it combines elements of different ideologies and is partly contradictory. Obama dealt with various conflicts in different ways: he dealt realistically with "wars of necessity" (Afghanistan) and agreement with the liberal internationalist approach to conflicts such as Libya. While Obama's flexibility might be considered a weakness by some, as he did not follow a firm and marked policy, it can also be seen as the necessary adaptation to a continuously changing environment. On many occasions a US president, such as Bush Jr., has pursued a rigid foreign policy, ideologically speaking, that ultimately achieved little practical success written request .

Another example of a variant of the conventional doctrine that sample the author gives is the "anti-doctrine" carried out by Trump. The man who was to be president until 2021 implemented a policy characterised by numerous contradictions and variations on the role that the US had been playing in the world, thereby casting doubt and uncertainty on the expected behaviour of the American superpower. This was due to Trump's political inexperience, both domestically and domestically, which caused concern not only among international actors but also at the core of Washington itself.

From the analysis of the different doctrines presented in the book, we can see how each of them is adapted to a specific social, historical and political context, and at the same time they all respond to a shared political tradition of a country that, as a superpower, manifests certain constants when it comes to maintaining peace and guaranteeing security. But these constants should not be confused with universal aspects, as each country has its own particularities and interests: simply adapting US positions to the foreign policy plans of other countries can lead to chaotic failures if these differences are not recognised.

For example, countries like Spain, which depend on EU membership, would not be able to enter into random wars unilaterally as the US has done. However, Spain could adopt some elements, such as in subject of decision-making, as this subject of doctrines makes it much easier to objectify and standardise the processes of analysis and resolutions.

Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelans and pending TPS termination for Central Americans amid a migration surge at the US-Mexico border

The Venezuelan flag near the US Capitol [Rep. Darren Soto].

ANALYSIS / Alexandria Angela Casarano

On March 8, the Biden administration approved Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for the cohort of 94,000 to 300,000+ Venezuelans already residing in the United States. Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti await the completion of litigation against the TPS terminations of the Trump administration. Meanwhile, the US-Mexico border faces surges in migration and detention facilities for unaccompanied minors battle overcrowding.

TPS and DED. The case of El Salvador

TPS was established by the Immigration Act of 1990 and was first granted to El Salvador that same year due to a then-ongoing civil war. TPS is a temporary immigration benefit that allows migrants to access education and obtain work authorization (EADs). TPS is granted to specific countries in response to humanitarian, environmental, or other crises for 6, 12, or 18-month periods-with the possibility of repeated extension-at the discretion of the Secretary of Homeland Security, taking into account the recommendations of the State Department.

The TPS designation of 1990 for El Salvador expired on June 30,1992. However, following the designation of Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) to El Salvador on June 26, 1992 by George W. Bush, Salvadorans were allowed to remain in the US until December 31, 1994. DED differs from TPS in that it is designated by the US President without the obligation of consultation with the State Department. Additionally, DED is a temporary protection from deportation, not a temporary immigration benefit, which means it does not afford recipients a legal immigration status, although DED also allows for work authorization and access to education.

When DED expired for El Salvador on December 31, 1994, Salvadorans previously protected by the program were granted a 16-month grace period which allowed them to continue working and residing in the US while they applied for other forms of legal immigration status, such as asylum, if they had not already done so.

The federal court system became significantly involved in the status of Salvadoran immigrants in the US beginning in 1985 with the American Baptist Churches v. Thornburgh (ABC) case. The ABC class action lawsuit was filed against the US Government by more than 240,000 immigrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and former Soviet Bloc countries, on the basis of alleged discriminatory treatment of their asylum claims. The ABC Settlement Agreement of January 31, 1991 created a 240,000-member immigrant group (ABC class members) with special legal status, including protection from deportation. Salvadorans protected under TPS and DED until December 31, 1994 were allowed to apply for ABC benefits up until February 16, 1996.

Venezuela and the 2020 Elections

The 1990's Salvadoran immigration saga bears considerable resemblance to the current migratory tribulations of many Latin American immigrants residing in the US today, as the expiration of TPS for four Latin American countries in 2019 and 2020 has resulted in the filing of three major lawsuits currently working their way through the US federal court system.

Approximately 5 million Venezuelans have left their home country since 2015 following the consolidation of Nicolás Maduro, on economic grounds and in pursuit of political asylum. Heavy sanctions placed on Venezuela by the Trump administration have exacerbated-and continue to exacerbate, as the sanctions have to date been left in place by the Biden administration-the severe economic crisis in Venezuela.

An estimated 238,000 Venezuelans are currently residing in Florida, 67,000 of whom were naturalized US citizens and 55,000 of whom were eligible to vote as of 2018. 70% of Venezuelan voters in Florida chose Trump over Biden in the 2020 presidential elections, and in spite of the Democrats' efforts (including the promise of TPS for Venezuelans) to regain the Latino vote of the crucial swing state, Trump won Florida's 29 electoral votes in the 2020 elections. The weight of the Venezuelan vote in Florida has thus made the humanitarian importance of TPS for Venezuela a political issue as well. The defeat in Florida has probably made President Biden more cautious about relieving the pressure on Venezuela's and Cuba's regimes.

The Venezuelan TPS Act was originally proposed to the US Congress on January 15, 2019, but the act failed. However, just before leaving office, Trump personally granted DED to Venezuela on January 19, 2021. Now, with the TPS designation to Venezuela by the Biden administration on March 8, Venezuelans now enjoy a temporary legal immigration status.

The other TPS. Termination and ongoing litigation

Other Latin American countries have not fared so well. At the beginning of 2019, TPS was designated to a total of four Latin American countries: Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti. Nicaragua and Honduras were first designated TPS on January 5, 1999 in response to Hurricane Mitch. El Salvador was redesignated TPS on March 9, 2001 after two earthquakes hit the country. Haiti was first designated TPS on January 21, 2010 after the Haiti earthquake. Since these designations, TPS was continuously renewed for all four countries. However, under the Trump administration, TPS was allowed to expire without renewal for each country, beginning with Nicaragua on January 5, 2019. Haiti followed on July 22, 2019, then El Salvador on September 9, 2019, and lastly Honduras on January 4, 2020.

As of March 2021, Salvadorans account for the largest share of current TPS holders by far, at a total of 247,697, although the newly eligible Venezuelans could potentially overshadow even this high figure. Honduras and Haiti have 79,415 and 55,338 TPS holders respectively, and Nicaragua has much fewer with only 4,421.

The elimination of TPS for Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti would result in the deportation of many immigrants who for a significant continuous period of time have contributed to the workforce, formed families, and rebuilt their lives in the United States. Birthright citizenship further complicates this reality: an estimated 270,000 US citizen children live in a home with one or more parents with TPS, and the elimination of TPS for these parents could result in the separation of families. Additionally, the conditions of Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti-in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, recent natural disasters (i.e. hurricanes Matthew, Eta, and Iota), and other socioeconomic and political issues-remain far from ideal and certainly unstable.

Three major lawsuits were filed against the US Government in response to the TPS terminations of 2019 and 2020: Saget v. Trump (March 2018), Ramos v. Nielsen (March 2018), and Bhattarai et al. v. Nielsen (February 2019). Kirstjen Nielsen served as Secretary of Homeland Security for two years (2017 - 2019) under Trump. Saget v. Trump concerns Haitian TPS holders. Ramos v. Nielsen concerns 250,000 Salvadoran, Nicaraguan, Haitain and Sudanese TPS holders, and has since been consolidated with Bhattarai et al. v. Nielsen which concerns Nepali and Honduran TPS holders.

All three (now two) lawsuits appeal the TPS eliminations for the countries involved on similar grounds, principally the racial animus (i.e. Trump's statement: "[Haitians] all have AIDS") and unlawful actions (i.e. violations of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA)) of the Trump administration. For Saget v. Trump, the US District Court (E.D. New York) blocked the termination of TPS (affecting Haiti only) on April 11, 2019 through the issuing of preliminary injunctions. For Ramos v. Nielson (consolidated with Bhattarai et al. v. Nielson), the US Court of Appeals of the 9th Circuit has rejected these claims and ruled in favour of the termination of TPS (affecting El Salvador, Nicaragua, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, and Sudan) on September 14, 2020. This ruling has since been appealed and is currently awaiting revision.

The US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have honored the orders of the US Courts not to terminate TPS until the litigation for these aforementioned cases is completed. The DHS issued a Federal Register Notice (FRN) on December 9, 2020 which extends TPS for holders from Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti until October 14, 2021. The USCIS has similarly cooperated and has ordered that so long as the litigation remains effective, no one will lose TPS. The USCIS has also ordered that in case of TPS elimination once the litigation is completed, Nicaragua and Haiti will have 120 grace days to orderly transition out of TPS, Honduras will have 180, and El Salvador will have 365 (time frames which are proportional to the number of TPS holders from each country, though less so for Haiti).

The Biden Administration's Migration Policy

On the campaign trail, Biden repeatedly emphasized his intentions to reverse the controversial immigration policies of the Trump administration, promising immediate cessation of the construction of the border wall, immediate designation of TPS to Venezuela, and the immediate sending of a bill to create a "clear [legal] roadmap to citizenship" for 11 million+ individuals currently residing in the US without legal immigration status. Biden assumed office on January 20, 2021, and issued an executive order that same day to end the government funding for the construction of the border wall. On February 18, 2021, Biden introduced the US Citizenship Act of 2021 to Congress to provide a legal path to citizenship for immigrants residing in the US illegally, and issued new executive guidelines to limit arrests and deportations by ICE strictly to non-citizen immigrants who have recently crossed the border illegally. Non-citizen immigrants already residing in the US for some time are now only to be arrested/deported by ICE if they pose a threat to public safety (defined by conviction of an aggravated felony (i.e. murder or rape) or of active criminal street gang participation).

Following the TPS designation to Venezuela on March 8, 2021, there has been additional talk of a TPS designation for Guatemala on the grounds of the recent hurricanes which have hit the country.

On March 18, 2021, the Dream and Promise Act passed in the House. With the new 2021 Democrat majority in the Senate, it seems likely that this legislation which has been in the making since 2001 will become a reality before the end of the year. The Dream and Promise Act will make permanent legal immigration status accessible (with certain requirements and restrictions) to individuals who arrived in the US before reaching the age of majority, which is expected to apply to millions of current holders of DACA and TPS.

If the US Citizenship Act of 2021 is passed by Congress as well, together these two acts would make the Biden administration's lofty promises to create a path to citizenship for immigrants residing illegally in the US a reality. Since March 18, 2021, the National TPS Alliance has been hosting an ongoing hunger strike in Washington, DC in order to press for the speedy passage of the acts.

The current migratory surge at the US-Mexico border

While the long-term immigration forecast appears increasingly more positive as Biden's presidency progresses, the immediate immigration situation at the US-Mexico border is quite dire. Between December 2020 and February 2021, the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported a 337% increase in the arrival of families, and an 89% increase in the arrival of unaccompanied minors. CBP apprehensions of migrants crossing the border illegally in March 2021 have reached 171,00, which is the highest monthly total since 2006.

Currently, there are an estimated 4,000 unaccompanied minors in CBP custody, and an additional 15,000 unaccompanied minors in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

The migratory CBP facility in Donna, TX designated specifically to unaccompanied minors has been filled at 440% to 900% of its COVID-19 capacity of just 500 minors since March 9, 2021. Intended to house children for no more than a 72-hour legal limit, due to the current overwhelmed system, some children have remained in the facility for more than weeks at a time before being transferred on to HHS.

In order to address the overcrowding, the Biden administration announced the opening of the Delphia Emergency Intake Site (next to the Donna facility) on April 6, 2021, which will be used to house up to 1,500 unaccompanied minors. Other new sites have been opened by HHS in Texas and California, and HHS has requested the Pentagon to allow it to temporarily utilize three military facilities in these same two states.

Political polarization has contributed to a great disparity in the interpretation of the recent surge in migration to the US border since Biden took office. Termed a "challenge" by Democrats and a "crisis" by Republicans, both parties offer very different explanations for the cause of the situation, each placing the blame on the other.

Iranian hackers forged pre-election mailings of the Proud Boys, but the actual post-election performance of this and other groups was more disruptive.

If in the 2016 US presidential election foreign meddling operations were led by Russia, in the 2020 election the focus was on Iranian hackers, because of the novelty they represented in a field of operations where Russians and Chinese were equally active, each pursuing their own interests. In particular, Tehran wanted a defeat for Donald Trump so that his Democratic successor would reverse the tough sanctions regime imposed against the Iranian regime. But these cyberspace actions by Iran, Russia and China were ineffective due to the heightened alertness of US security and intelligence agencies. In the end, these outside attempts to discredit US democracy and undermine voter confidence in its electoral system were dwarfed by the damage caused by the domestic chaos itself.

Assault on the Capitol in Washington on 6 January 2021 [TapTheForwardAssist].

article / María Victoria Andarcia

Russia was always in the US security spotlight during the 2020 election year, after its meddling in the presidential election four years earlier. However, while the main concern remained Russia and there were also fears of an expansion of China's operations, Iran made headlines in some of the warnings issued by the US authorities, probably because of the ease with which they were able to attribute various actions to Iranian actors. Despite this multiple front, the development polling did not yield any evidence that foreign disinformation campaigns had been effective. The swift identification of the actors involved and the offensive reaction by US security and intelligence services could have prevented the 2016 status . As the Atlantic Council has noted, this time 'domestic disinformation overshadowed foreign action'.

Given the direct consequences that Joe Biden's arrival in the White House may have on Washington's policy towards Iran, this article pays more attention to Iran's attempts to affect the US election development . The impact of Iranian operations was minimal and had a smaller profile impact than those carried out by Russia in 2016 (which in turn had less involvement than in previous elections).

Iranian operations

In May and June 2020, the first movements in Microsoft accounts were recorded, as the company itself would later reveal. An Iranian group called Phosphorus had succeeded in gaining access to the accounts of White House employees and Trump's re-election campaign team. These were early signs that Tehran was setting up some kind of cyber operation. subject

In early August, the Center for Counterintelligence and National Security's director , William Evanina, accused Tehran - as well as Moscow and Beijing - of using disinformation on the internet to "influence voters, unleash disorder and undermine public confidence" in the system. Regarding Iran, it said: "We assess that Iran seeks to undermine US democratic institutions and President Trump, and to divide the country ahead of the 2020 election". She added that Iranian efforts were focused on spreading disinformation on social media, where it circulated anti-US content. Evanina attributed the motivation for these actions to Iranian perceptions "that President Trump's re-election would result in a continuation of US pressure on Iran in an effort to encourage regime change".

Following the televised discussion between Trump and Biden on 29 September, Twitter deleted 130 accounts that "appeared to originate in Iran" and whose content, which it had placed on knowledge by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), was intended to influence public opinion during the discussion presidential election. The company provided only four examples. Two of the accounts were pro-Trump: one Username was @jackQanon (at reference letter to the conspiratorial group QAnon) and the other expressed support for the Proud Boys, a far-right organisation with supremacist links to which Trump had order "be on guard and be vigilant". The other two accounts had expressed pro-Biden messages.

In mid-October, director of National Intelligence, John Ratcliffe, referred on press conference to Iranian and Russian cyber action as a threat to the electoral process. According to Ratcliffe, the Iranian operation consisted primarily of a series of emails purporting to be sent by the group Proud Boys. The emails contained threats of physical force for those who did not vote for Trump, and were intended to instigate violence and damage Trump's image by associating his campaign with radical groups and efforts to intimidate voters. Interestingly, the Proud Boys would later gain prominence for themselves in the post-election rallies in Washington and the takeover of the Capitol.

department While Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Said Jatibzadeh denied these accusations, stressing that "Iran is indifferent to who wins the US elections", the US authorities insisted on their version and the US Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned five Iranian entities for attempting to undermine the presidential elections. According to OFAC'sstatement , the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and the Quds Force used Iranian media as platforms to spread propaganda and disinformation to the US population.

agreement According to OFAC, business Iranian audiovisual media company Bayan Gostar, a regular Revolutionary Guard collaborator, had "planned to influence the election by exploiting social problems within the United States, including the COVID-19 pandemic, and by denigrating US political figures". The Islamic Iranian Radio and Television Union (IRTVU), which OFAC considers a propaganda arm of the Revolutionary Guard, and the International Virtual Media Union "assisted Bayan Gostar in his efforts to reach US audiences". These media outlets "amplified false narratives in English and published derogatory propaganda articles and other content directed at the United States with the intent to sow discord among US audiences".

Post-election performance

The US claims that Iranian interference was not limited to the election, which took place on 3 November (with an unprecedented level of advance and postal voting), but continued in the weeks that followed, seeking to take advantage of the turmoil caused by the Trump administration's questioning of the result election. Days before Christmas, the FBI and department 's Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) revealed that Iran was allegedly behind a website and several social media accounts aimed at provoking further violence against various US officials. The website entitled "Enemies of the People" contained photographs and information staff of both officials and staff from the private sector who were involved in the process of counting and authenticating votes cast in the election, sometimes in the face of allegations of fraud maintained by Trump and his supporters.

The action attributed to Iran can be interpreted as a way to avenge the drone strike ordered by Washington to assassinate Qasem Soleimani, head of the Qurds Force in Iraq, for whose death on 3 January 2020 Tehran had vowed retaliation. But above all it reveals a continuing effort by Iran to alleviate the effects of the Trump-driven US policy of 'maximum pressure'. Given Biden's stated intention during the election campaign to change US foreign policy towards the Islamic Republic, the latter would have the opportunity to receive a looser US attention if Trump lost the presidential election. Biden had indicated that if he came to power he would change policy towards Iran, possibly returning to the nuclear agreement signed in 2015 on the condition that Iran respect the limits on its nuclear programme agreed at the time. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was considered a milestone in the foreign policy of then President Barack Obama, but then the Trump administration decided not to respect it because it considered that issues such as Iran's missile development and its military interference in other countries in the region had been left out.

A few days before the inauguration of the new US president, Iranian President Hassan Rohani urged Biden to lift the sanctions imposed on the Islamic Republic and return to the 2015 nuclear agreement . Iran hopes that the Biden administration will take the first steps to compensate for the actions of the previous administration and thus move towards a possible understanding between the two nations. The decision to return to agreement will not be made immediately as Biden inherits a divided country and it will take time to reverse Trump's policies. With the Iranian presidential elections approaching in June this year, the Biden administration is buying time to attempt a reformulation that will not be easy, as the context of the Middle East has changed substantially over the past five years.

The inclusion of private investment and the requirement of efficient credits differ from the overwhelming amount of loans from Chinese state banks.

The active role of China as lender to an increasing number of countries has forced the United States to try to compete in this area of "soft power". Until last decade the US was clearly ahead of China in official development assistance, but Beijing has used its state-controlled banks to pour loans into ambitious projects worldwide. In order to better compete with China, Washington has created the US International Development Finance Corporation (USIDFC), combining the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and with USAID's Development Credit Authority (DCA).

▲ The US agency helped to provide clean, safe, and reliable sanitation for more than 100,000 people in Nairobi, at the end of 2020 [USIDFC].

ARTICLE / Alexandria Casarano

It is not easy to know the complete amount of the international loans given by China in recent years, which skyrocketed from the middle of last decade. Some estimates say that the Chinese state and its subsidiaries have lent about US$ 1.5 trillion in direct loans and trade credits to more than 150 countries around the globe, turning China into the world's largest official creditor.

The two main Chinese foreign investment banks, the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank, were both established in 1994. The banks have been criticised for their lack of transparency and for blurring the lines between official development assistance (ODA) and commercial financial arrangements. To address this issue, Beijing founded the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) in April of 2018. The CIDCA will oversee all Chinese ODA activity, and the Chinese Ministry of Commerce will oversee all commercial financial arrangements going forward.

An additional complaint about Chinese foreign investment concerns "debt-trap diplomacy." Since the PRC first announced its "One Belt One Road" initiative in 2013, the Chinese government has steadily increased its investment in the developing world even more dramatically than it had in the early 2000's (when Chinese foreign aid was increasing annually by approximately 14%). At the 2018 China-Africa Convention Forum, the PCR pledged to invest US$ 60 billion in Africa that year alone. The Wall Street Journal said of the PRC in 2018 that it was "expanding its investments at a pace some consider reckless." Ray Washburn, president of the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), called the Chinese One Belt One Road initiative a "loan-to-own" program. In 2018, this was certainly the case with the Chinese funded Sri Lankan port project, which led the Sri Lankan government to lease the port to Beijing for a 99-year period as a result of falling behind on payments.

OPIC, founded in 1971 under the Nixon administration, was recommended for elimination in the Trump administration's 2017 budget. However, following the beginning of the US-China trade war in 2018, Washington reversed course completely. President Trump's February 2018 budget recommended increasing OPIC's funding and combining it with other government programs. These recommendations manifested themselves in the Better Utilization of Investment Leading to Development (BUILD) Act, which was passed by Congress on October 5, 2018. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) called the BUILD Act "the most important piece of U.S. soft power legislation in more than a decade."

The US International Development Finance Corporation

The principal achievement of the BUILD Act was the creation of the US International Development Finance Corporation (USIDFC), which began operation as an independent agency on December 20, 2019. The BUILD Act combined OPIC with USAID's Development Credit Authority to form the USIDFC and established an annual budget of US$ 60 billion for the new organisation, which is more than double OPIC's 2018 budget of US$ 29 billion.

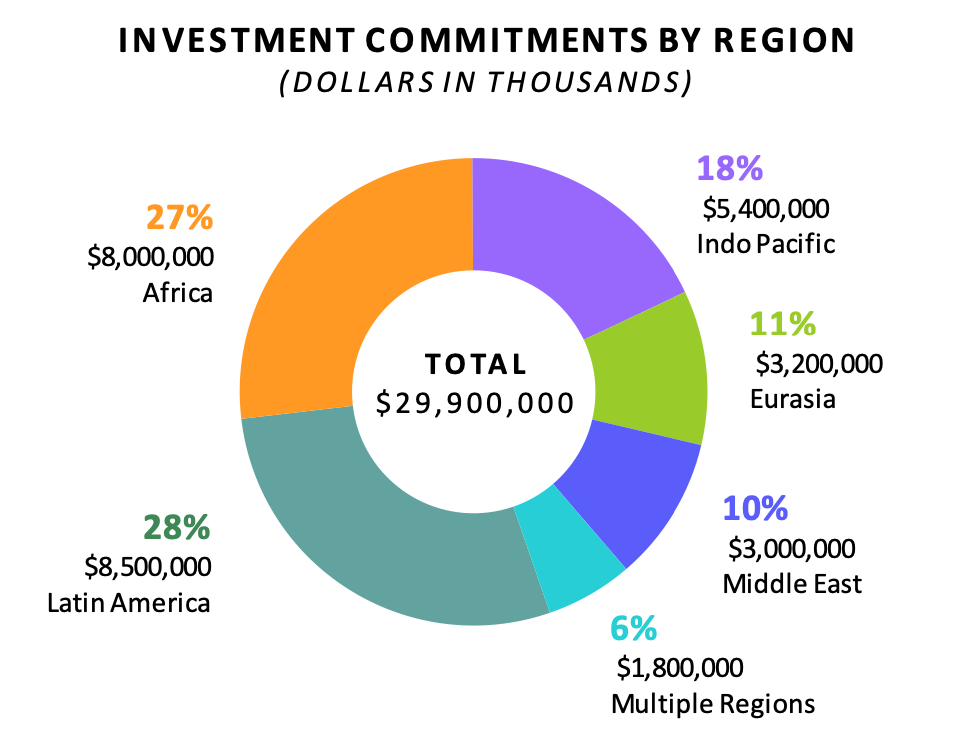

USIDFC's investment commitments by region for the FY 2020. The US$ 29.9 billion is only a fraction of the agency's budget [USIDFC].

According to the Wall Street Journal, OPIC "has been profitable every year for the last 40 years and has contributed US$ 8.5 billion to deficit reduction," a financial success which can primarily be attributed to project management fees. As of 2018, OPIC managed a portfolio valued at US$ 23 billion. OPIC's strong fiscal track record, combined with both the concept of government program streamlining and the larger context of geopolitical competition with China, generated bipartisan support for the BUILD Act and the USIDFC.

The USIDFC has several key new capacities which OPIC lacked. OPIC's business was limited to "loan guarantees, direct lending and political-risk insurance," and suffered under a "congressional cap on its portfolio size and a prohibition on owning equity stakes in projects". The USIDFC, however, is permitted under the BUILD Act to "acquire equity or financial interests in entities as a minority investor."

Both the USIDFC currently and OPIC before its incorporation are classified as Development Finance Institutions (DFIs). DFIs seek to "crowd-in" private investment, that is, attracting private investment that would not occur otherwise. This differs from the Chinese model of state-to-state lending and falls in line with traditional American political and economic philosophy. According to the CSIS, "The USIDFC offers [...] a private sector, market-based solution. Moreover, it fills a clear void that Chinese financing is not filling. China does not support lending to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and it rarely helps local companies in places like Africa or Afghanistan grow".

In the fiscal year of 2020, the most USIDFC's investments were made in Latin America (US$ 8.5 billion) and Sub-Saharan Africa (US$ 8 billion). Lesser but still significant investments were made in the Indo-Pacific region (US$ 5.4 billion), Eurasia (US$ 3.2 billion), and Middle East (US$ 3 billion). This falls in line with the USIDFC's goal to invest more in lower and lower-middle income countries, as opposed to upper middle countries. OPIC previously had fallen into the pattern of investing predominantly in upper-middle countries, and while the USIDFC is still legally authorised to invest in upper-middle income countries for national security or developmental motives.

These investments serve to further US national interests abroad. According to the USIDFC webpage, "by generating economic opportunities for citizens in developing countries, challenges such as refugees, drug-financed gangs, terrorist organisations, and human trafficking can all be addressed more effectively". Between 2002 and 2014, financial commitments in the DFI sector have increased sevenfold, from US$ 10 billion to US$ 70 billion. In our increasingly globalized world, international interests increasingly overlap with national interests, and public interests increasingly overlap with private interests.

Ongoing USIDFC initiatives

The USIDFC has five ongoing initiatives to further its national interests abroad: 2X Women's Initiative, Connect Africa, Portfolio for Impact and Innovation, Health and Prosperity, and Blue Dot Network. In 2020, the USIDFC "committed to catalyzing an additional US$ 6 billion of private sector investment in global women's economic empowerment" by joining the 2X Women's Initiative which seeks global female empowerment. About US$1 billion for this US$ 6 billion commitment has been specially pledged to Africa. Projects that fall under the 2X Women's Initiative include equity financing for a woman-owned feminine hygiene products online store in Rqanda, and "expanding women's access to affordable mortgages in India".

Continuing the USIDFC's special focus on Africa follows the Connect Africa initiative, under which the USIDFC has pledged US$ 1 billion to promote economic growth and connectivity in Africa. The Connect Africa initiative involves investment in telecommunications, internet access, and infrastructure.

Under the Portfolio for Impact and Innovation initiative, the USIDFC has dedicated US$ 10 million to supporting early-stage businesses. This includes sponsoring the Indian company Varthana, which offers affordable online learning for children whose schools have been shut down due to the Covid-19 crisis.

The Health and Prosperity initiative focuses on "bolstering health systems" and "expanding access to clean water, sanitation, and nutrition". Under the Health and Prosperity initiative, the USIDFC has dedicated US$ 2 billion to projects such as financing a 200+ mile drinking water pipeline in Jordan.

The Blue Dot Network initiative, like the Connect Africa initiative, also invests in infrastructure, but on a global scale. The Blue Dot Network initiative differs from the aforementioned initiatives in being a network. Launched in November 2019, the Blue Dot Network seeks to align the interests of government, private enterprise, and civil society to facilitate the successful development of infrastructure around the globe.

It is important to note that these five initiatives are not entirely separate. Many projects fall under several initiatives at once. The Rwandan feminine products e-store project, for example, falls under both the 2X Women's initiative and the Health and Prosperity initiative.

[Barack Obama, A Promised Land (discussion: Madrid, 2020), 928 pp.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

A president's memoirs are always an attempt to justify his political actions. Having employee George W. Bush used less than five hundred pages in "Decision Points" to try to explain the reasons for a more controversial management in principle, that Barack Obama used almost a thousand pages for the first part of his memoirs (A promised land The fact that no US president has ever required so much space in this exercise of wanting to tie up his bequest.

A president's memoirs are always an attempt to justify his political actions. Having employee George W. Bush used less than five hundred pages in "Decision Points" to try to explain the reasons for a more controversial management in principle, that Barack Obama used almost a thousand pages for the first part of his memoirs (A promised land The fact that no US president has ever required so much space in this exercise of wanting to tie up his bequest.

It is true that Obama has a taste for the pen, with some previous books in which he has already demonstrated good storytelling, and it is possible that this literary inclination has won him over. But probably more decisive has been Obama's vision of himself and his presidency: the conviction of having a mission statement, as the first African-American president, and his ambition to bend the arc of history. As time goes by and Obama starts to become just another in the list of presidents, his book vindicates the historic character of his person and his achievements.

The first third of A Promised Land is particularly interesting. There is a brief overview of his life before entrance in politics and then the detail of his degree program to the White House. This part has the same inspirational charge that made so attractive My Father's Dreams, the book that Obama published in 1995 when he launched his campaign for the Illinois Senate (in Spain it appeared in 2008, following his campaign for the presidency). We can all draw very useful lessons for our own self-improvement staff: the idea of being masters of our destiny, of becoming aware of our deepest identity, and the security that this gives us to carry out many enterprises of great value and transcendence; to put all our efforts into a goal and take advantage of opportunities that may not come again; in final, to always think outside the box (when Obama saw that his work as senator of Illinois had little impact, his decision was not to leave politics, but to jump to the national level: He ran for senator in Washington and from there, just four years later, he reached the White House). The pages are also rich in lessons on political communication and election campaigns.

But when the narrative begins to address the presidential term, which began in January 2009, that inspirational tone drops. What was once a succession of generally positive adjectives towards everyone begins to include diatribes against his Republican opponents. And here is the point that Obama is unable to overcome: giving himself all the moral credit and denying it to those whose votes in the congress disagreed with the legislation promoted by the new president. It is true that Obama had a very frontal civil service examination from the Republican leaders in the Senate and the House of Representatives, but they also supported some of his initiatives, as Obama himself acknowledges. For the rest, which came first, the chicken or the egg? Large swathes of Republicans were quick to jump on the bandwagon, as the Tea Party tide in the 2010 midterm elections soon made clear (in a movement that would eventually lead to support for Trump), but Obama had also arrived with the most left-leaning positions in US politics in living memory. With his idealistic drive, Obama had set little example of bipartisan effort in his time in the Illinois and Washington Senate; when some of his reforms from the White House were blocked in the congress, instead of seeking accommodation - accepting a politics of the possible - he took to the streets to pit citizens against politicians who opposed his transformations, further entrenching the trenches of one side against the other.

The British historian Niall Ferguson has pointed out that the Trump phenomenon would not be understood without Obama's previous presidency, although the bitter political divide in the United States is probably a matter of a deep current in which leaders play a less central role than we might suppose. Obama saw himself as ideally suited, because of his cultural mix (black, but raised by his white mother and grandparents), to bridge the widening rift in US society, but he was unable to build the necessary ideological bridges. Bill Clinton faced a similar Republican blockade, in the congress led by Newt Gingrich, and made compromises that were useful: he reduced ideological baggage and brought an economic prosperity that relaxed public life.

A Promised Land includes many of Obama's reflections. He generally provides the context necessary to understand the issues, for example in the gestation of the 2008 financial crisis. In foreign policy he details the state of relations with major powers: animosity towards Putin and suspicion of China, among other issues. There are areas with different possible ways forward where Obama leaves no room for a legitimate alternative position: thus, in a particularly emblematic topic , he charges Netanyahu without admitting any mistakes of his own in his approach to the Israeli-Palestinian problem. This is something that other reviews of the book have noted: the absence of self-criticism (beyond admitting sins of omission in not having been as bold as he might have wished), and the failure to admit that in some respects perhaps the opponent might have been right.

The narrative is well-paced internally, despite the many pages. The volume ends in 2011, at a random point in time determined by the anticipated length of a second submission; however, it has a sufficiently strong climax: the operation against Osama bin Laden, for the first time told in the first person by the person at the highest level of command. Although the Degree involvement of other hands in the essay of the work is unknown, it has a point of lyricism that connects directly with Los sueños de mi padre (My Father's Dreams) and which financial aid leads us to attribute it, at least to a large extent, to the former president himself.

The book contains many episodes of the Obamas' domestic life. Obama's constant compliments to his wife, admiration for his mother-in-law and constant references to his devotion to his two daughters might be considered unnecessary, especially as they recur, in a political book. Nonetheless, they give the story the tone staff that Obama has sought to adopt, as well as giving human warmth to someone who has often been accused of having a public image of being cold, distant and overly reflective.

![Joe Biden and Barack Obama in February 2009, one month after arriving at the White House [Pete Souza]. Joe Biden and Barack Obama in February 2009, one month after arriving at the White House [Pete Souza].](/documents/16800098/0/biden-obama-blog.jpg/ad49fcda-889d-4b84-14cc-87cf326fc61c?t=1621883654693&imagePreview=1)

Joe Biden and Barack Obama in February 2009, one month after arriving at the White House [Pete Souza].

COMMENTARY / Emili J. Blasco

This article was previously published, in a somewhat abbreviated form, in the newspaper 'Expansión'.

One of the great mistakes revealed by the US presidential election is to have underestimated the figure of Donald Trump, believing him to be a mere anecdote, and to have disregarded much of his politics as whimsical. In reality, the Trump phenomenon is a manifestation, if not a consequence, of the current American moment, and some of his major decisions, especially in the international arena, have more to do with domestic imperatives than with fickle whimsy. The latter suggests that there are aspects of foreign policy, manners aside, in which Joe Biden as president may be closer to Trump than to Barack Obama, simply because the world of 2021 is already somewhat different from that of the first half of the previous decade.

First, Biden will have to confront Beijing. Obama began to do so, but the more assertive character of Xi Jinping's China has been accelerating in recent years. In the superpower tug-of-war, especially over the dominance of the new technological age, the US has everything at stake vis-à-vis China. It is true that Biden has referred to the Chinese not as enemies but as competitors, but the trade war was already begun by the administration of which he was vice-president and now the objective rivalry is greater.

Nor is the US's withdrawal the result of Trump's madness. Basically it has to do, to simplify somewhat, with the energy independence achieved by the Americans: they no longer need oil from the Middle East and no longer have to be in all the oceans to ensure the free navigation of tankers. America First' has in a way already been started by Obama and Biden will not go in the opposite direction. So, for example, no major involvement in EU affairs and no firm negotiations for a free trade agreement between the two Atlantic markets can be expected.

On the two major achievements of the Obama era - the agreement nuclear deal with Iran sealed by the US, the EU and Russia, and the restoration of diplomatic relations between Washington and Havana - Biden will find it difficult to tread the path then defined. There may be attempts at a new rapprochement with Tehran, but there would be greater coordination against it on the part of Israel and the Sunni world, which are now more convergent. Biden may find that less pressure on the ayatollahs pushes Saudi Arabia towards the atom bomb.

As for Cuba, a return to dissent will be more in the hands of the Cuban government than of Biden himself, who in his electoral loss in Florida has been able to read a rejection of any condescension towards Castroism. Some of the new restrictions imposed by Trump on Cuba may be dismantled, but if Havana continues to show no real willingness to change and open up, the White House will no longer have to continue betting on political concessions to credit .

In the case of Venezuela, Biden is likely to roll back a good part of the sanctions, but there is no longer room for a policy of inaction like Obama's. That administration did not confront Chavismo for two reasons. That Administration did not confront Chavismo for two reasons: because it did not want to upset Cuba, given the secret negotiations it was holding with that country to reopen its embassies, and because the regime's level of lethality had not yet become unbearable. Today, international human rights reports are unanimous on the repression and torture of Maduro's government, and the arrival of millions of Venezuelan refugees in the different countries of the region means that it is necessary to take action on the matter. Here it is to be hoped that Biden will be able to act less unilaterally and, while maintaining pressure, seek coordination with the European Union.

It is often the case that those who come to the White House deal with domestic affairs in their first years and then later, especially in a second term, focus on leaving an international bequest . Due to age and health, the new occupant may only serve a four-year term. Without Obama's idealism of wanting to 'bend the arc of history' - Biden is a pragmatist, a product of the US political establishment - or businessman Trump's rush for immediate gain, it is hard to imagine that his administration will take serious risks on the international stage.

Biden has confirmed his commitment to begin his presidency in January by reversing some of Trump's decisions, notably on climate change and the Paris agreement ; on some tariff fronts, such as the outgoing administration's unnecessary punishment of European countries; and on various immigration issues, especially concerning Central America.

In any case, even if the Democratic left wants to push Biden to the margins, believing that they have an ally in Vice President Kamala Harris, the president-elect can make use of his staff moderation: the fact that in the elections he obtained a better result than the party itself gives him, for the moment, sufficient internal authority. The Republicans have also held their own quite well in the Senate and the House of Representatives, so that Biden comes to the White House with less support on Capitol Hill than his predecessors. That, in any case, may help to reinforce one of the Delaware politician's generally most valued traits today: predictability, something that the economies and foreign ministries of many of the world's countries are eagerly awaiting.

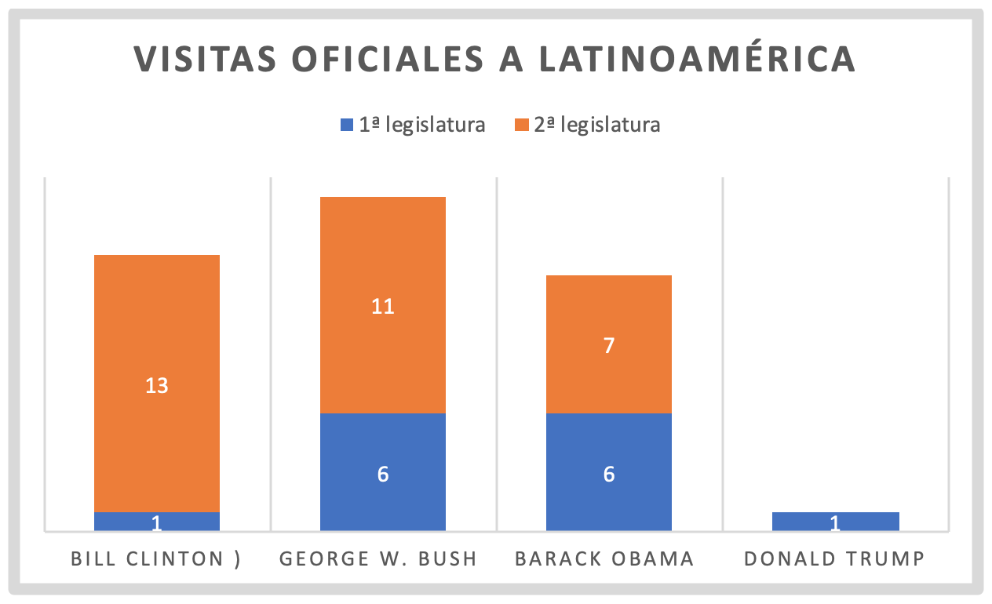

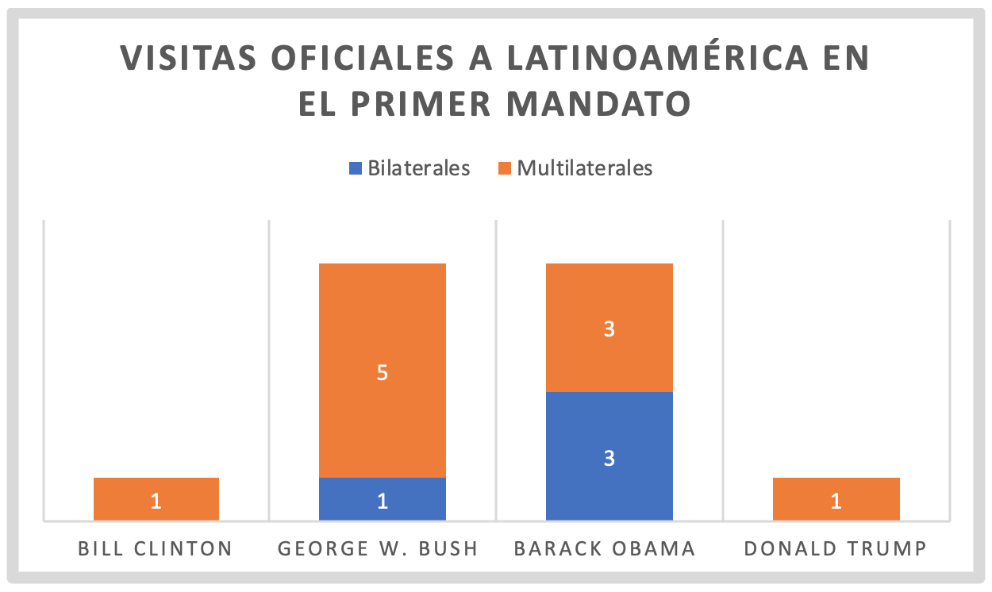

The current president made only one visit, also at the framework of the G-20, compared to the six that Bush and Obama made in their first four years.

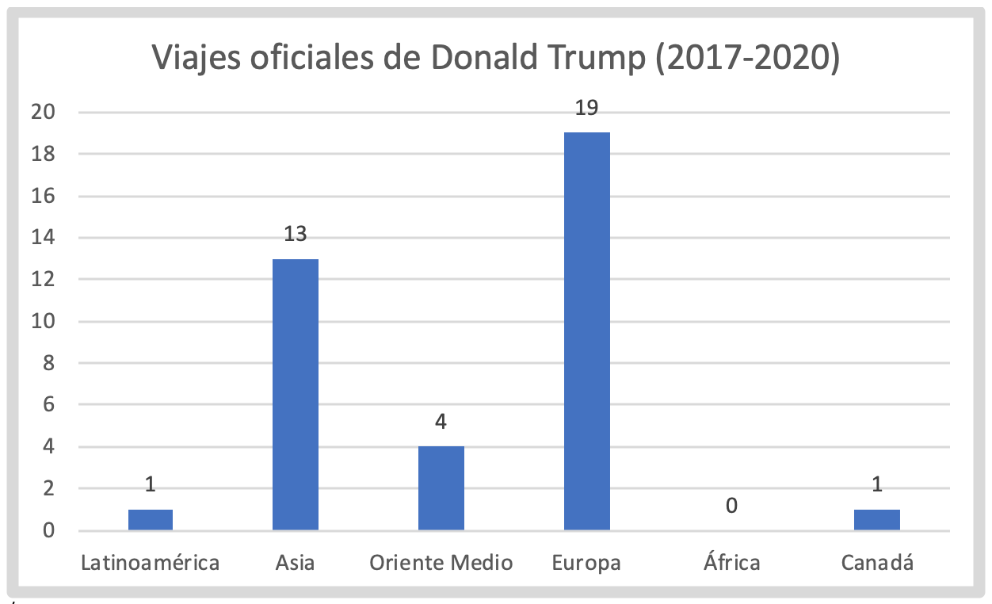

International travel does not tell the whole story about a president's foreign policy, but it does give some clues. As president, Donald Trump has only travelled once to Latin America, and then only because the G20 summit he was attending was being held in Argentina. It is not that Trump has not dealt with the region - of course, Venezuela policy has been very present in his management- but the fact that he has not made the effort to travel to other countries on the continent reflects the more unilateral character of his policy, which is not very focused on gaining sympathy among his peers.

![signature in Mexico in 2018 of the free trade agreement between the three North American countries [department of State, USA]. signature in Mexico in 2018 of the free trade agreement between the three North American countries [department of State, USA].](/documents/16800098/0/viajes-trump-blog.jpg/157ee6c8-c573-2e22-6911-3ae54fe8a0a8?t=1621883760733&imagePreview=1)

▲ signature in Mexico in 2018 of the free trade agreement between the three North American countries [department of State, USA].

article / Miguel García-Miguel

With only one visit visit to the region, the US president is the one who has made the fewest official visits since Clinton's first term in office, who also visited the region only once. In contrast, Bush and Obama paid more attention to the neighbouring territory, both with six visits in their first term. Trump focused his diplomatic campaign on Asia and Europe and reserved Latin American affairs for visits by the region's presidents to the White House or his Mar-a-Lago resort.

In reality, the Trump administration spent time on Latin American issues, taking positions more quickly than the Obama administration, as the worsening problem in Venezuela required defining actions. At the same time, Trump has discussed regional issues with Latin American presidents during their visits to the US. There has not, however, been an effort at multilateralism or empathy, going to his meeting in their home countries to deal with their problems there.

Clinton: Haiti

The Democratic president made only one visit to the region during his first term in office: visit . refund After the Uphold Democracy operation to bring Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power, on 31 March 1995 Bill Clinton travelled to Haiti for the transition ceremony organised by the United Nations. The operation had consisted of a military intervention by the United States, Poland and Argentina, with UN approval, to overthrow the military board that had forcibly deposed the democratically elected Aristide. During his second term, Clinton paid more attention to regional affairs, with thirteen visits.

Bush: free trade agreements

Bush made his first presidential trip to neighbouring Mexico, where he met with then President Fox to discuss a range of issues. Mexico paid attention to the US government's attention attention to Mexican immigrants, but the two presidents also discussed the functioning of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which came into force in 1994, and joint efforts in the fight against drug trafficking. The US president had the opportunity to visit Mexico three more times during his first term in office for the purpose of attend multilateral meetings. Specifically, in March 2002, he attended the lecture International Meeting on Financing for the development, organised by the United Nations and which resulted in the Monterrey Consensus; Bush also took the opportunity to meet again with the Mexican president. In October of the same year he attended the APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) summit, which that year was held in the Mexican enclave of Los Cabos. Finally, he set foot on Mexican soil once again to attend the Special Summit of the Americas held in Monterrey in 2004.

During his first term in office, Bush pushed for the negotiation of new free trade agreements with several American countries, which was the hallmark of his administration's policy towards the Western Hemisphere. framework As part of this policy, he travelled to Peru and El Salvador on 23 and 24 March 2002. agreement In Peru, he met with the President of Peru and the Presidents of Colombia, Bolivia and Ecuador, in order to reach an agreement to renew the ATPA (Andean Trade Promotion Act), by which the US granted tariff freedom on a wide range of exports from these countries. The matter was finally resolved with the enactment in October of the same year of the ATPDEA (Andean Trade Promotion and Drug Eradication Act), which maintained tariff freedoms in compensation for the fight against drug trafficking, in an attempt to develop the region economically in order to create alternatives to cocaine production. Finally, in the case of El Salvador, he met with the Central American presidents to discuss the possibility of a Free Trade Agreement with the region (known in English as CAFTA) in exchange for a strengthening of security in the areas of the fight against drug trafficking and terrorism. The treaty was ratified three years later by the US congress . Bush revisited Latin America up to eleven times during his second term.

Graph 1. Own elaboration with data of Office of the Historian

Obama: two Summits of the Americas

Obama began his tour of diplomatic visits to Latin America with attendance to the Fifth Summit of the Americas, held in Port-au-Prince (Trinidad and Tobago). The Summit brought together all the leaders of the sovereign countries of the Americas, with the exception of Cuba, and was aimed at coordinating efforts to recover from the recent crisis of 2008, with mentions of the importance of environmental and energy sustainability. Obama returned to attend in 2012 to the VI Summit of the Americas held this time in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia). No representatives from Ecuador or Nicaragua attended this summit in protest at the exclusion of Cuba to date. Neither the President of Haiti nor Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez attended, citing medical reasons. At the summit, the issues of Economics and security were once again discussed, with the war on drugs and organised crime being of particular relevance, as well as the development of environmental policies. He also took advantage of this visit to announce, together with Juan Manuel Santos, the effective entrance of the Free Trade Agreement between Colombia and the US, negotiated by the Bush Administration and ratified after some delay by the US congress . The Democratic president also had the opportunity to visit the region on the occasion of the G-20 meeting in Mexico, meeting , but this time the main focus of topic was on solutions to curb the European debt crisis.

In terms of bilateral meetings, Obama undertook a diplomatic tour of Brazil, Chile and El Salvador between 19 and 23 March 2010, meeting with their respective presidents. He used the occasion to resume relations with the Brazilian left that had governed the country since 2002, to reiterate his economic and political alliance with Chile, and to announce a $200 million fund to strengthen security in Central America. During his second term in office, he made up to seven visits, including the resumption of diplomatic relations with Cuba, which had been paused since the triumph of the Revolution.

Trump: T-MEC

Donald Trump only visited Latin America on one occasion to attend meeting the G-20, a meeting that was not even regional, held in Buenos Aires in December 2018. Among the various agreements reached were the reform of the World Trade Organisation and the commitment of the attendees to implement the measures adopted at the Paris agreement , with the exception of the US, since the president had already reiterated his determination to withdraw from the agreement. Taking advantage of the visit, he signed the T-MEC (Treaty between Mexico, the United States and Canada, the new name for the renewed NAFTA, the renegotiation of which Trump had demanded) and met with the Chinese president in the context of the trade war. Trump, on the other hand, did not attend the VIII Summit of the Americas held in Peru in April 2018; the trip, which was also supposed to take him to Colombia, was cancelled at the last minute because the US president preferred to remain in Washington in the face of a possible escalation of the Syrian crisis.

The reason for the few visits to the region has been that Trump has directed his diplomatic campaign towards Europe, Asia and to a lesser extent the Middle East, in the context of the trade war with China and the loss of power on the US international stage.

Graph 2. Own elaboration with data of Office of the Historian

Only one trip, but monitoring of the region

Despite having hardly travelled to the rest of the continent, the Republican candidate has paid attention to the region's affairs, but without leaving Washington, as up to seven Latin American presidents have visited the White House. The main focus of the meetings has been the economic development and the reinforcement of security, as usual. Depending on the reality of each country, the meetings revolved more around the possibility of future trade agreements, the fight against drugs and organised crime, preventing the flow of illegal immigration to the United States, and the search to strengthen political alliances. Although the US government website does not list it as an official visit , Donald Trump also met at the White House in February 2020 with Juan Guaidó, recognised as president in charge of Venezuela.

Precisely, if there has been a common topic to all these meetings, it has been the status economic and political crisis in Venezuela. Trump has sought allies in the region to encircle and put pressure on Maduro's government, which is not only an example of continuous human rights violations, but also destabilises the region. The ironclad civil service examination to the regime served Donald Trump as propaganda to gain popularity and try to save the Latino vote in the November 3 elections, and that had its award at least in the state of Florida.

Graph 3. Own elaboration with data of Office of the Historian

COMMENTARY / Rafael Calduch Torres*.

As tradition dictates since 1845, on the first Tuesday of November, the 3rd, the eligible voters of the fifty states that make up the United States will take part in the fifty-ninth Election Day, the day on which the high school Electoral, which will have to choose between keeping the forty-fifth President of the United States of America, Donald Trump, or electing the forty-sixth, Joe Biden.

But the real problem facing not only the inhabitants of the US, but also the rest of the world's population, is that both Trump and Biden are setting out their international strategy at core topic domestically, following in the wake of the change that took place in the country following the 9/11 attacks and whose fundamental result has been the absence of effective leadership of the American superpower over the last twenty years. For if there is one thing that must be clear to us, it is the fact that none of the candidates, like their predecessors, has a plan to restore the international leadership that the United States enjoyed until the end of the 1990s; On the contrary, what they are urged to do is to solve domestic problems and subordinate international issues, which a superpower of the stature of the US must face, to the solutions adopted domestically. This is one of the serious strategic errors of our era, since strong international leaderships that are coherent with the management of domestic problems have historically allowed the creation of points of meeting in US society that cushion divisions and bring the country together.

However, despite these broad similarities, there is a clear difference between the two candidates in their approach to international issues that will affect the outcome of the choice Americans will make on Tuesday.

"The Power of America's example. With this slogan, Biden's general proposal , much clearer and more accessible than Trump's, develops a plan to lead the democratic world in the 21st century based on using the way in which America's domestic problems will be solved as an example, binding and sustaining its international leadership; it goes without saying that the mere assumption that America's domestic problems are not exactly extrapolable to the rest of the international actors is not even taken into account.

Thus, the Democratic candidate , using a fairly traditional rhetoric on the dignity of leadership, uses the connection between domestic and international reality to propose a programme of national regeneration without specifying how this will succeed in re-establishing the lost international leadership. This approach will be based on two main pillars: the democratic regeneration of the country and the reconstruction of the US class average which, in turn, will underpin other international projects.

Democratic regeneration will be based on strengthening the educational and judicial systems, transparency, the fight against corruption and an end to attacks on the media, and is seen as the instrument for restoring the country's moral leadership, which, in addition to inspiring others, would serve for the US to transfer these US domestic policies to the international arena, for others to follow and imitate through a sort of global league for democracy that seems very nebulous to us.

Meanwhile, the reconstruction of the class average , the same one Trump appealed to four years ago, would involve greater investment in technological innovation and supposedly greater global equity in international trade, from which the United States would benefit the most.

Finally, all of the above would be complemented by a new era in international arms control through a new START treaty between the US and Russia, US leadership in the fight against climate change, an end to interventions on foreign soil, particularly in Afghanistan, and the re-establishment of diplomacy as the backbone of US foreign policy.

"Promises Made, Promises Kept!What is Trump's alternative? The current President does not reveal what his projects are, but he does propose a review of his "achievements" which, we understand, will give us an idea of what his foreign policy will be, which will revolve around the continuity of the US trade rebalancing based, as until now, on shielding US companies from foreign investment, the imposition of new tariffs, the fight against fraudulent trade practices, especially on the part of China, and the restoration of US relations with its allies in Asia/Pacific, the Middle East and Europe, but without specific proposals.

With regard to security, which Trump treats differently, the recipe is increased defence spending, the shielding of US territory against terrorism and opposition to North Korea, Venezuela and Iran, to which will be added the maintenance and expansion of the recent campaign of actions directed specifically against Russia, with the declared goal to contain it in Ukraine and to prevent cyber-attacks.

But the reality is that both candidates will have to face global challenges that they have not considered in their programmes and that will decisively condition their mandates, starting with the management of the pandemic and its economic effects on a global scale and including the growing competition from the European Union, especially as its common military and defence capabilities develop.

As we have just seen, none of the candidates will offer new solutions and therefore the situation is unlikely to improve, at least in the short term deadline.

* PhD in Contemporary History. graduate in Political Science and Administration. Lecturer at the UNAV and the UCJC.

[Bruno Maçães, History Has Begun. The Birth of a New America. Hurst and Co. London, 2020. 203 p.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

What if the United States were not in decline, but quite the opposite? The United States could actually be in its infancy as a great power. This is what Bruno Maçães argues in his new book, whose degree scroll -History Has Begun- In a certain sense, he refutes Fukuyama's end of history, which saw the democratisation of the world at the end of the 20th century as the culmination of the West. Precisely, the hypothesis of the Portuguese-born internationalist is that the US is developing its own original civilisation, separate from what until now has been understood as Western civilisation, in a world in which the very concept of the West is losing strength.

What if the United States were not in decline, but quite the opposite? The United States could actually be in its infancy as a great power. This is what Bruno Maçães argues in his new book, whose degree scroll -History Has Begun- In a certain sense, he refutes Fukuyama's end of history, which saw the democratisation of the world at the end of the 20th century as the culmination of the West. Precisely, the hypothesis of the Portuguese-born internationalist is that the US is developing its own original civilisation, separate from what until now has been understood as Western civilisation, in a world in which the very concept of the West is losing strength.

Maçães' work follows three lines of attention: the progressive separation of the US from Europe, the characteristics that identify the specific American civilisation, and the struggle between the US and China for the new world order. The author had already developed aspects of these themes in his two immediately preceding works, already reviewed here: The Dawn of Eurasia y Belt and RoadThe focus is now on the US. The three titles are basically a sequence: the progressive dissolution of the European peninsula into the Eurasian continent as a whole, the emergence of China as the superpower of this great continental mass, and Washington's remaining role on the planet.

As to whether the US is rising or not leave, Maçães writes in the book's introduction: "Conventional wisdom suggests that the United States has already reached its peak. But what if it is only now beginning to forge its own path forward? The volume is written before the coronavirus crisis and the deep unease in US society today, but even before that some signs of US domestic unrest, such as political polarisation or divergences over the direction of its foreign policy, were already evident. "The present moment in the history of the United States is both a moment of destruction and a moment of creation", says Maçães, who considers that the country is going through "convulsions" characteristic of this process of destructive creation. In his opinion, in any case, they are "the birth pangs of a new culture rather than the death throes of an old civilisation".

One might think that the United States is simply evolving towards a mixed culture as a result of globalisation, so that the influence of some European countries in shaping US society over the last few centuries is now being joined by Asian immigration. Indeed, by mid-century, immigrants from across the Pacific are expected to outnumber those arriving from Mexico and Central America, which, although steeped in indigenous cultures, largely follow the Western paradigm. Between the first European and the new Asian heritage, a 'hybrid Eurasian' culture could develop in the US.

Indeed, at one point in the book, Maçães asserts that the US is 'no longer a European nation', but 'in fundamental respects now seems more similar to countries like India or Russia or even the Republic of Iran'. However, he disagrees with this hybrid Eurasian perspective and argues instead for the development of a new, indigenous American society, separate from modern Western civilisation, rooted in new sentiments and thoughts.

In describing this different way of being, Maçães focuses on a few manifestations, from which he deduces deeper aspects. "Why do Americans speak so loudly?" he asks, referring to one such symptom. His theory is that American life emphasises its own artificiality as a way of reminding its participants that they are, at bottom, experiencing a story. "The American way of life is consciously about language, storytelling, plot and form, and is meant to draw attention to its status as fiction." An entire chapter, for example, is devoted to analysing the importance of television in the US. In the midst of these considerations, the reader might think that the reasoning has been drifting towards a cultural essay and out of the realm of International Office, but in the conclusion of the book the ends are conveniently tied up.

With that loose end out of the way, the book moves on to analyse the tug of war between Washington and Beijing. It recalls that since its rise as a world power around 1900, the US's permanent strategic goal has been to prevent a single power from controlling the whole of Eurasia. Previous threats in this regard were Germany and the USSR, and today it is China. employee Normally, Washington would resort to a balance of power, using Europe, Russia and India against China (using a game historically played by Britain for the goal to prevent a single country from controlling the European continent), but for the moment the US has focused on directly confronting China. Maçães sees the Trump administration's policy as confusing. "If the US wants to adopt a strategy of maximum pressure against Beijing, it needs to be clearer about the end game": is it to constrain Chinese economic power or to convert China to the West's model ?, he asks. He intuits that the ultimate goal is to "decouple" the Western world from China, creating two separate economic spheres.

Maçães believes that China will hardly manage to dominate the supercontinent, since "the unification of the whole of Eurasia under a single power is so far from inevitable that in fact it has never been achieved". In any case, he believes that, because of its interest as a superpower, the US may end up playing not so much the role of "great balancer" (given China's weight, it is difficult for any of its neighbours to exercise a counterweight) as that of "great creator" of the new order. "China must be trimmed down in size and other pieces must be accumulated, if a balance is to be the final product," he asserts.

It is here that the US character as a story and narrative builder finally comes back into the picture, with a somewhat flimsy argument. Maçães can see the US succeeding in this task of "great maker" if it treats its allies with autonomy. As in a novel, his role as narrator "is to bring all the characters together and preserve their own individual spheres"; "the narrator has learned not to impose a single truth on the whole, and at the same time no character will be allowed to replace him". "For the United States," Maçães concludes, "the age of nation-building is over. The age of world building has begun".

![Crossroads in Minneapolis where George Floyd was stopped by local police [Fibonacci Blue]. Crossroads in Minneapolis where George Floyd was stopped by local police [Fibonacci Blue].](/documents/10174/16849987/george-floyd-blog.jpg)

▲ Crossroads in Minneapolis where George Floyd was stopped by local police [Fibonacci Blue].

COMMENTARY / Salvador Sánchez Tapia [Brigadier General (Res.)].

In a controversial public statement on 2 June, US President Donald Trump threatened to deploy armed forces units to contain riots sparked by the death of African-American George Floyd at the hands of a police officer in Minnesota, and to maintain law and order if they escalate in violence.

Regardless of the seriousness of the event, and beyond the fact that the incident has been politicised and is being employee used as a platform for expressing rejection of Trump's presidency, the possibility raised by the president poses an almost unprecedented challenge to civil-military relations in the United States.

For reasons rooted in its pre-independence past, the United States maintains a certain caution against the possibility that armed forces can be used domestically against citizens by whoever holds power. For this reason, when the Founding Fathers drafted the Constitution, while authorising the congress to organise and maintain armies, they explicitly limited their funding to a maximum of two years.

Against this backdrop, and against the background of the tension between the Federation and the states, American legislation has tried to limit the employment of the Armed Forces in domestic tasks. Thus, since 1878, the Posse Comitatus Since 1878, for example, the Armed Forces Act has limited the possibility of using them to carry out law and order missions that the states, including the National Guard, are responsible for carrying out with their own resources.

One of the exceptions to this rule is the Insurrection Act of 1807, invoked precisely by President Trump as an argument in favour of the legality of a possible decision by employment. This is despite the fact that this law is restrictive in spirit, as it requires the cooperation of the states in its application, and because it is designed for extreme cases in which the states are unable, or unwilling, to maintain order, circumstances that do not seem applicable to the case at hand.

The controversial nature of advertisement is attested to by the fact that voices as authoritative and so little inclined to publicly break its neutrality as that of Lieutenant General (ret.) James Mattis, Secretary of Defence of the Trump Administration until his premature removal in December 2018, or Lieutenant General (ret.) Martin Dempsey, head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff between 2011 and 2015, have spoken out against it. ) Martin Dempsey, head of the board Chiefs of Staff between 2011 and 2015, have spoken out against this employment, joining the statements made by former presidents as disparate as George W. Bush and Barack Obama, or those of the Secretary of Defence himself, Mark Esper, whose position against the possibility of using the Armed Forces in this status has recently been made clear.

The presidential advertisement has opened up a crisis in the usually stable US civil-military relations (CMR). Beyond the scope of the United States, the profound question, which affects the very core of CMR in a democratic state, is none other than whether or not it is appropriate to use the armed forces in public order or, in a broader sense, domestic tasks, and the risks associated with such a decision.

In the 1990s, Michael C. Desch, one of the leading authorities in the field of CMR, identified the correlation between the missions entrusted to the armed forces by a state and the quality of its civil-military relations, concluding that foreign-oriented military missions are the most conducive to healthy CMR, while non-military domestic missions are likely to generate various CMR pathologies.

Generally speaking, the existence of armed forces in any state is primarily motivated by the need to protect the state against any threat from outside. employment In order to carry out such a high task with guarantees, armies are equipped and trained for the lethal use of force, unlike police forces, which are equipped and trained for a minimal and gradual use of force, which only becomes lethal in the most extreme, exceptional cases. In the first case, it is a matter of confronting an armed enemy intent on destroying one's own forces. In the second, force is used to confront citizens who may, in some cases, use violence, but who remain, after all, compatriots.

When military forces are employed in tasks of this nature, there is always a risk that they will produce a response in accordance with their training, which may be excessive in a law and order scenario. The consequences, in such a case, can be very negative. In the worst case, and above all other considerations, the employment may result in a perhaps avoidable loss of life. Moreover, from the CMR's point of view, the soldiers that the nation submission has for its external defence could become, in the eyes of the public, the enemies of those they are supposed to defend.

The damage this can do to civil-military relations, to national defence and to the quality of a state's democracy is difficult to measure, but it can be intuited if one considers that, in a democratic system, the armed forces cannot live without the support of their fellow citizens, who see them as a beneficial force for the nation and to whose members they extend their recognition as its loyal and selfless servants.

The abuse of employment of the armed forces in domestic tasks can also deteriorate their already complex preparation, weakening them for the execution of the missions for which they were conceived. It may also end up conditioning their organisation and equipment to the detriment, once again, of their essential tasks.