Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

![A view of the Badshahi Mosque, in Lahore, capital of the Punjab province [Pixabay]. A view of the Badshahi Mosque, in Lahore, capital of the Punjab province [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-mayo-2020-blog.jpg)

▲ A view of the Badshahi Mosque, in Lahore, capital of the Punjab province [Pixabay].

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS REPORT / Naomi Moreno, Alejandro Puigrefagut, Ignacio Yárnoz

Download the document [pdf. 1,4MB] [pdf. 1,4MB

Download the document [pdf. 1,4MB] [pdf. 1,4MB

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report has been aimed at examining the future prospects for Pakistan in the 2025 horizon in relation to other States and to present various scenarios through a prospective strategic analysis.

The research draws upon the fact that, despite the relatively short space of time, Pakistan is likely to undergo several important changes in its international affairs and thus feel forced to rethink its foreign policy. This strategic analysis suggests there could be considerable estrangement between the U.S. and Pakistan and, therefore, the American influence will decrease considerably. Their security alliance could terminate, and Pakistan would cease to be in U.S.' sphere of influence. Moreover, with the new BRI and CPEC projects, China could move closer to Pakistan and finally become its main partner in the region. The CPEC is going to become a vital instrument for Pakistan, so it could significantly increase Chinese influence. Yet, the whole situation risks jeopardizing Pakistan's sovereign independence.

India-Pakistan longstanding dispute over Kashmir seems to be stagnated and will possibly remain as such in the following years. India has taken steps to annex its administered territory in Jammu and Kashmir and Pakistan could potentially follow. The possibility of an open conflict and a nuclear standoff remains possible as both nuclear powers have very different strategies and conceptions which could lead to misinterpretation and a nuclear escalation.

In the quest to rethink its foreign policy, the U.S.-Taliban peace and the empowerment of the group has come as a bolt from the sky for Pakistan. Through its ties with the Taliban, Pakistan could gain itself a major presence in the region namely by reaching out to Central Asia and advance its interest to curtail India's influence. Amid a dire economic crisis, with regards to the Saudi Iranian Cold War, Pakistan could seek a way in which it can recalibrate its stance in favour of the resource-rich Saudi alliance while it appeases sectarian groups who could strongly oppose this potential policy.

Pakistan ought to acknowledge that significant changes ought to be made in both the national and international sphere and that decisive challenges lay ahead.

Beijing has announced the construction of a fifth base, matching the US base at issue .

While there is widespread international monitoring of the major powers' position-taking in the Arctic, given that global warming opens up trade routes and possibilities for resource exploitation, geopolitical movements around Antarctica go more unnoticed. With any national claims to the South Pole continent frozen by existing agreements, the steps taken by the superpowers are minor but significant. As in the Arctic, China is a new player, and is stepping up its stakes.

![Shared camp for research scientists in Antarctica [Pixabay]. Shared camp for research scientists in Antarctica [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/antartida-china-blog.jpg)

▲ Shared camp for research science in Antarctica [Pixabay].

article / Jesús Rizo

Antarctica is the southernmost continent and at the same time the most extreme due to its geographical and thermal conditions, which seriously limit its habitability. Human presence is almost impossible in the so-called East Antarctic, which is two thousand metres above sea level and makes up more than two thirds of the continent, making it the highest altitude continent average. Moreover, since Antarctica is not an ocean, as is the Arctic, it is not affected, except in its continental perimeter, by the increase in sea temperatures due to climate change.

To these difficulties for human presence are added the limitations imposed by international provisions, which have applied a moratorium on any claim to sovereignty or commercial exploitation, something that does not happen in the Arctic. Action in Antarctica is strongly determined by the Antarctic Treaty (Washington, 1959) which, in its articles I and IX, reservation the continent for research scientific and peaceful purposes. In addition, it prohibits nuclear explosions and the disposal of radioactive waste (article V), and any non-peaceful military action (article I).

protocol This treaty is complemented and developed by three other documents: the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR, Canberra, 1980), the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (CCFA, London, 1988) and the Antarctic Treaty on Environmental Protection (Madrid, 1991), which prohibits "any activity related to mineral resources, except for scientific research " until 2048. At final, the so-called Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) "shields" the Antarctic region from exploitation of its resources and increased international tensions, as it also freezes territorial claims for as long as it is in force. However, this does not prevent global powers from also seeking a foothold in Antarctica.

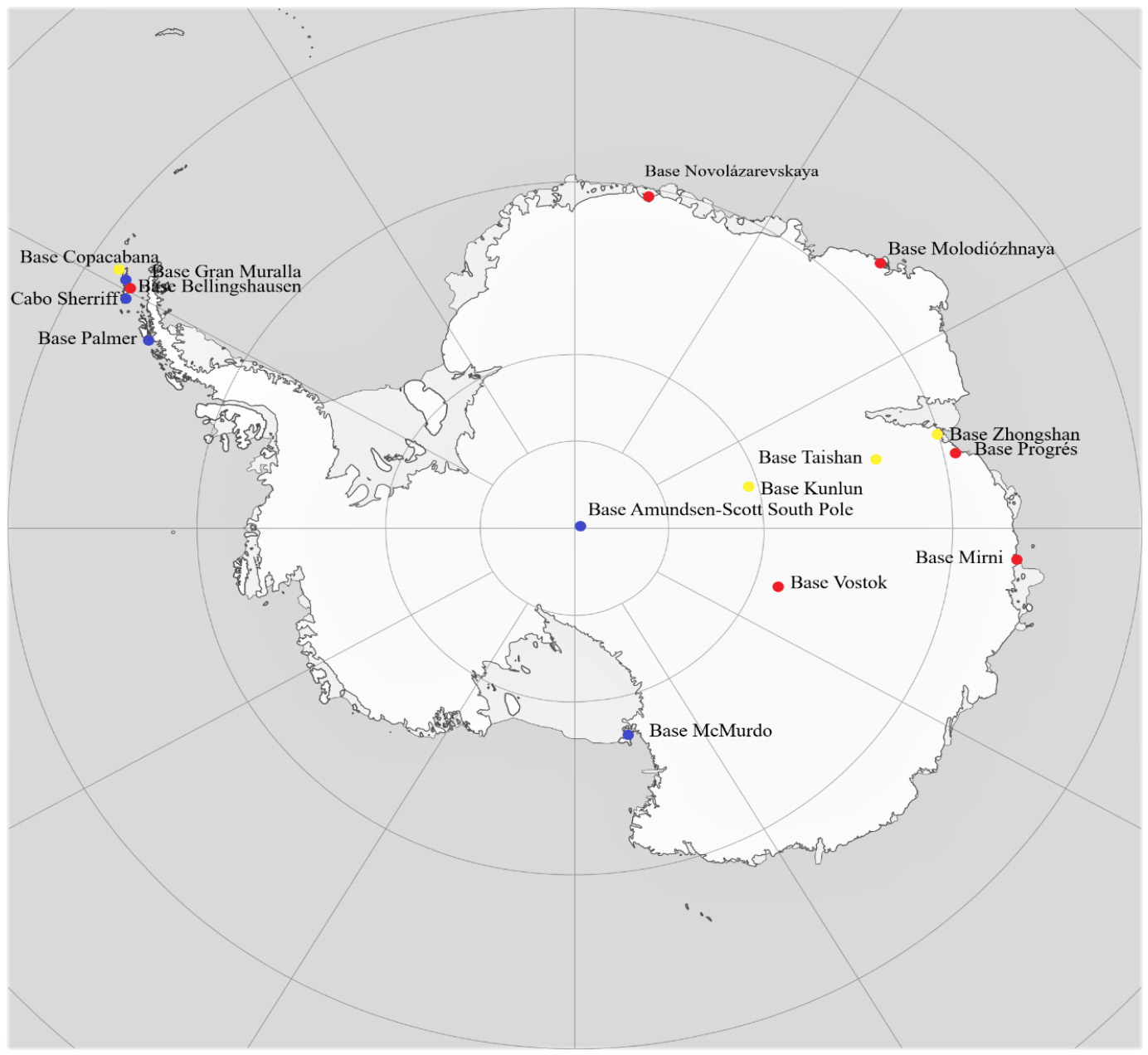

The most recent action corresponds to the People's Republic of China, which aspires to play a major role in the area, as is the case in the Arctic. Already with four scientific instructions sites on the southern continent (the Antarctic instructions Great Wall, Zhongshan, Kunlun and Taishan, the first two permanent and the last two functional in summer), last November it announced the construction of its fifth base (thus equalling the United States at issue ). The new facility, in the Ross Sea, would be operational by 2022.

In relation to these scientific stations, since Xi Jinping came to power in 2013, China has been seeking to create a Specially Managed Antarctic Zone for the protection of the environment around the Kunlun base, something resisted by its regional neighbours, as it would give Beijing dominion over the activities carried out there. This is China's most important base, essential for its programs of study at subject astronomy and, therefore, for the development of the BeiDou, China's satellite navigation system, which is essential for the expansion and modernisation of its armed forces and rivals the GPS (US), Galileo (EU) and GLONASS (Russia) systems. In this respect, and in view of the military implications of Antarctica, the Treaty established the possibility for any country to carry out inspections of any of the instructions sites there, as a way of ensuring compliance with the provisions of agreement (article VII). However, the danger and cost of these inspections have meant that they have been considerably reduced, not to mention that the Kunlun base is located in one of the most climatically hostile regions of the continent.

On the other hand, China currently has two icebreakers, the Xue Long I and the Xue Long II, the latter built entirely on Chinese territory with the Finnish Aker Arctic attendance . Experts believe that, following the construction of this vessel, the People's Republic could be close to building nuclear-powered icebreakers, something that is currently only undertaken by Russia and which would have global consequences.

But the importance of Antarctica for China is not only reflected in the technical and technological advances it is making, but also in its bilateral relations with countries close to the southern continent such as Chile and Brazil, the former with original consultative status and with a territorial claim in the ATS, and the latter with consultative status only. Last September, the Andean country held the first meeting of the Joint Antarctic Cooperationcommittee with the People's Republic, in which, among other matters, the use of the port of Punta Arenas by China as a base for the supply of staff and materials to its Antarctic installations was discussed, conversations that will require further deepening. business As for Brazil, China's CEIEC (China National Electronics Import & Export Corporation) financed a new Brazilian Antarctic base worth $100 million in January.

Approximate location of the main Antarctic instructions . In blue, the US instructions , in red, the Russian , and in yellow, the Chinese .

Finally, it is worth analysing the weight of the US and Russia in Antarctica, although China is likely to be the most important player in the region, at least until the opening of the Madrid protocol for review in 2048. The United States has three permanent instructions (the instructions McMurdo, Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station and Palmer) and two summer only (the instructions Copacabana and Cape Shirreff), so the construction of the new Chinese base will equal the issue total of the instructions US bases.

For its part, Russia, the dominant power in the Arctic, is also the dominant power in its southern counterpart, at least in terms of issue of instructions, since it has six, four of which operate annually (Mirni, Novolazarevskaya, Progrés and Vostok) and the other two only during the summer (Bellingshausen and Molodiózhnaya). However, it should be noted that Russia has not opened any Antarctic bases since the collapse of the USSR, the most recent being Progrés (1988), although it has tried, for example, to reopen the Soviet base Russkaya, without success. The United States also established most of its Antarctic instructions at the height of the Cold War, in the 1950s and 1960s, except for the two summer ones (Copacabana in 1985 and Cape Shirreff in 1991).

China, by contrast, opened the Great Wall base in 1985, the Zhongshan base in 1989, the Kunlun base in 2009 and the Taishan base in 2014 and, as mentioned above, has a new one pending for 2022.

In addition to the countries mentioned above, another twenty countries have instructions of research in Antarctica, including Spain, which has consultative status in the Antarctic Treaty. Spain has two summer instructions sites in the South Shetland Islands, the Juan Carlos I base (1988) and the Gabriel de Castilla base (1998). It also has a temporary scientific camp located on the Byers Peninsula of Livingston Island.

COMMENT / Carlos Jalil

Covid-19 has forced many states to take extraordinary measures to protect the welfare of their citizens. This includes the suspension of certain human rights on grounds of public emergency. Rights such as freedom of movement, freedom of expression, freedom of meeting and privacy are affected by state responses to the pandemic. We therefore ask: Do states unduly affect freedom of expression when combating fake news? Do they unduly restrict our freedom of movement and meeting or even deprive us of our liberty? Do they infringe on our right to privacy with new tracking apps? Is this justified?

To protect public health, human rights treaties allow states to adopt measures that may restrict rights. article agreement 4 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and article 15 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) provide that in situations of public emergency that threaten the life of the nation, states may take measures and derogate from their treaty obligations. Similarly, article 27 of the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), allows states parties to fail to derogate from their obligations in emergency situations that threaten the independence or security of the nation.

During the pandemic, some states have declared a state of emergency and, because of the impossibility of respecting certain rights, have derogated from their obligations. However, derogations are subject to requirements. General Comment 29 on States of Emergency of the UN Human Rights committee sets out six conditions for derogations, which are similar in the above-mentioned treaties: (1) official proclamation of a state of emergency and public emergency threatening the life of the nation; (2) proportionality required by the requirements of the status in terms of duration, geographical coverage and substantive basis; (3) non-discrimination (however the ECHR does not include this condition); (4) conformity with other international law obligations; (5) formal notification of the derogation to the respective treaty bodies (these must include full information on the measures, their reasons and documentation of laws adopted); and (6) prohibition of derogation from non-derogable rights.

The last condition is particularly important. The aforementioned treaties (ICCPR, ECHR and ACHR) explicitly set out the rights that cannot be derogated from. These, also called absolute rights, include, inter alia: right to life, prohibition of slavery and servitude, principle of legality and retroactivity of law, and freedom of conscience and religion.

However, derogations are not always necessary. There are rights that, on the contrary, are not absolute and have the inherent possibility of being limited, for which it is not necessary for a state to derogate from its treaty obligations. This means that the state, for public health reasons, may limit certain non-absolute rights without the need to give notice of derogation. These non-absolute rights are: the right to freedom of movement and meeting, freedom of expression, the right to liberty staff and privacy. Specifically, the right to freedom of movement and association is subject to limitations on grounds of national security, public order and health, or the rights and freedoms of others. The right to freedom of expression may be limited by respect for the rights or reputation of others and by the protection of national security, public order and public health. And the rights to freedom of expression staff and privacy may be subject to reasonable limitations in accordance with the provisions of human rights treaties.

Despite these possibilities, countries such as Latvia, Estonia, Argentina and Ecuador, which have officially declared a state of emergency, have resorted to derogation. Consequently, they have justified Covid-19 as an emergency threatening the life of the nation, notifying the United Nations, the Organisation of American States and Europe's committee of the derogation from their international obligations under the aforementioned treaties. In contrast, most states adopting extraordinary measures have not proceeded with such derogation, based on the inherent limitations of these rights. Among them are Italy and Spain, countries seriously affected, which have not derogated, but have applied limitations.

This is an interesting phenomenon because it demonstrates the differences in states' interpretations of international human rights law, also subject to their national legislatures. There is clearly a risk that states applying limitations abuse the state of emergency and violate human rights. It may therefore be that some states interpret derogations as reflecting their commitment to the rule of law and the principle of legality. However, human rights bodies are also likely to find the measures adopted by states that have not derogated consistent with the status pandemic. Excluding, in both cases, situations of torture, excessive use of force and other circumstances affecting absolute rights.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, courts and tribunals are likely to decide whether the measures adopted were necessary. But in the meantime, states should consider that extraordinary measures adopted should be temporary, in line with appropriate health conditions and within framework of the law.

[George Friedman. The Storm Before the Calm. America's Discord, the Coming Crisis of the 2020s, and the Triumph Beyond. Doubleday. New York, 2020. 235 pp.]

review / E. Villa Corta, E. J. Blasco

The degree scroll of the new book by George Friedman, the driving force behind the geopolitical analysis and intelligence agency Stratfor and later creator of Geopolitical Futures, does not refer reference letter to the global crisis created by the Covid-19 pandemic. When he speaks of the crises of the 2020s, which Friedman has been anticipating for some time in his commentaries and now explains at length in this book, he is referring to deep and long-lasting historical movements, in this case confined to the United States.

The degree scroll of the new book by George Friedman, the driving force behind the geopolitical analysis and intelligence agency Stratfor and later creator of Geopolitical Futures, does not refer reference letter to the global crisis created by the Covid-19 pandemic. When he speaks of the crises of the 2020s, which Friedman has been anticipating for some time in his commentaries and now explains at length in this book, he is referring to deep and long-lasting historical movements, in this case confined to the United States.

Beyond the current pandemic, therefore, which is somewhat circumstantial and not addressed in the text (its composition is previous), Friedman predicts that the US will reinvent itself at the end of this decade. Like a machine that, almost automatically, incorporates substantial changes and corrections every certain period of time, the US is preparing for a new leap. There will be a prolonged crisis, but the US will emerge triumphant, Friedman predicts. US decline? Quite the opposite.

Unlike Friedman's previous books, such as The Next Hundred Years or Flashpoints, this time Friedman moves away from Friedman's global geopolitical analysis to focus on the US. In his reflection on American history, Friedman sees a succession of cycles of roughly equal length. The current ones are already in their final stages, and the reinstatement of both will coincide in the late 2020s, in a process of crisis and subsequent resurgence of the country. In the institutional field, the 80-year cycle that began after the end of World War II is coming to an end (the previous one had lasted since the end of the Civil War in 1865); in the socio-economic field, the 50-year cycle that began with Ronald Reagan in 1980 is coming to an end (the previous one had lasted since the end of the Great Recession and the arrival of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the White House).

Friedman does not see Donald Trump as the catalyst for change (his effort has simply been to recover the status created by Reagan for the class average working class, affected by unemployment and loss of purchasing power), nor does he believe that whoever replaces him in the coming years will be the catalyst. Rather, he places the turnaround around 2028. The change, which is taking place in a time of great turmoil, will have to do with the end of the technocracy that dominates American political and institutional life and with the creative disruption of new technologies. The author wants to denote the US's skill ability to overcome adversity and take advantage of "chaos" in order to achieve fruitful growth.

Friedman divides the book into three parts: the creation of the nation as we know it, the cycles we have gone through, and the prognosis for the one to come. In this last part he presents the challenges or adversities that the country will have to face.

As for the creation of the country, the author reasons about the subject government created in the United States, the territory in which the country is located and the American people. This last aspect is perhaps the most interesting. He defines the American people as a purely artificial construct. This leads him to see the US as a machine that automatically fine-tunes its functioning from time to time. As an "invented" country, the US reinvents itself when its cycles run out of steam.

Friedman presents the training of the American people through three overlapping types: the cowboy, the inventor and the warrior. To the cowboy, who seeks to start something completely new and in an "American" way, we owe especially America's unique social construct. To the inventor belongs the drive for technological progress and economic prosperity. And the warrior condition has been present from the beginning.

The second part of the book deals with the aforementioned question of cycles. Friedman considers that US growth has been cyclical, a process in which the country reinvents itself from time to time in order to continue progressing. After reviewing the periods so far, he locates the next big change in the US in the decade that has just begun. He warns that the gestation of the next stage will be complicated by the accumulation of events from past cycles. One of the issues that the country will have to resolve concerns the paradox between the desire to internationalise democracy and human rights and that of maintaining its national security: "liberating the world" or securing its position in the international sphere.

The present moment of change, in which agreement with the author the institutional and the socio-economic cycle will collide, is a time of deep crisis, but will be followed by a long period of calm. Friedman believes that the first "tremors" of the crisis were felt in the 2016 elections, which showed a radical polarisation of US society. The country will have to reform not only its complex institutional system, but also various socio-economic aspects.

This last part of the book - devoted to solving problems such as the student debt crisis, the use of social networks, new social constructions or the difficulty in the sector educational- is probably the most important. If the mechanicity and automatism in the succession of cycles determined by Friedman, or even their very existence, are questionable (other analyses could lead other authors to consider different stages), the real problems that the country is currently facing are easily observable. So the presentation of proposals for their resolution is of undoubted value.

![Tourist town in Gjirokastër district, southern Albania [Pixabay]. Tourist town in Gjirokastër district, southern Albania [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/albania-ue-blog.jpg)

Tourist population in Gjirokastër district, southern Albania [Pixabay].

ESSAY / Jan Gallemí

On 24 November 2019, the French government of Enmanuel Macron led the veto, together with other states such as Denmark and the Netherlands, of the accession of the Balkan nations of Albania and North Macedonia to the European Union. According to the president of the French Fifth Republic, this is due to the fact that the largest issue of economic refugees entering France are from the Balkans, specifically from the aforementioned Albania. The latter country applied to join the European Union on 28 April 2009, and on 24 June 2014 it was unanimously agreed by the 28 EU countries to grant Albania the status of a country candidate for accession. The reasons for this rejection are mainly economic and financial.[1]. There is also a slight concern about the diversity that exists in the ethnographic structure of the country and the conflicts that this could cause in the future, not only within the country itself but also in its relationship with its neighbours, especially with the Kosovo issue and relations with Greece and North Macedonia.[2]. However, another aspect that has also been explored is the fact that Albania's accession would mean the EU membership of the first state in which the religion with the largest number of followers is Islamic, specifically the Sunni branch, issue . This essay will proceed to analyse the impact of this aspect and observe how, or to what extent, Albanian values, mainly because they are primarily Islamic in religion, may combine or diverge from those on which the common European project is based.

Evolution of Islam in Albania

One has to go back in history to consider the reasons why a European country like Albania has developed a social structure in which the religion most professed by part of the population is Sunni. Because of the geographical region in which it is located, it would theoretically be more common to think that Albania would have a higher percentage of Orthodox than Sunni population.[3]. The same is true for Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. This region was originally largely Orthodox Christian in the south (like most Balkan states today) due to the fact that it was one of the many territories that made up the Byzantine Empire until the 13th century, when the nation gained its independence. However, the reason why Islam is so present in Albania, unlike its neighbouring states, is that it was more religiously influenced by the Ottoman Empire, the successor to the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire fell in 1453 and its territories were occupied by the Ottomans, a Turkish people established at that time on the Anatolian peninsula. According to historians such as Vickers, it was between the 17th and 18th centuries that a large part of the Albanian population converted to Islam.[4]The reason for this, as John L. Esposito points out, was that for the Albanian population, changing their religion meant getting rid of the higher taxes that Christians had to pay in the Ottoman Empire.[5].

Religion in Albania has since been shaped by events. As far as we know from programs of study such as those of Gawrych in the 19th century, Albanian society was then divided mainly into three groups: Catholics, Orthodox and Sunnis (the latter represented 70% of the population). The same century saw the birth of many of the well-known European nationalisms and the beginning of the so-called Eastern crisis in the Balkans. During this period many Balkan peoples revolted against the Ottomans, but the Albanians, identifying with the Ottomans through their religion, initially remained loyal to the Sultan.[6]. Because of this support, Muslim Albanians began to be pejoratively referred to as "Turks".[7]. This caused Albanian nationalism to distance itself from the emerging Ottoman pan-Islamism of Sultan Abdualhmid II. This gave rise, according to Endresen, to an Albanian national revival called Rilindja, which sought the support of Western European powers.[8].

The Balkan independence movements that emerged in the 19th century generally reinforced Christian as opposed to Muslim sentiment, but in Albania this was not the case; as Stoppel points out, both Albanian Christians and Muslims cooperated in a common national goal .[9]. This encouraged the coexistence of both beliefs (already present in earlier times) and allowed the differentiation of this movement from Hellenism.[10]. It is worth noting that at that time in Albania Muslims and Christians were peculiarly distributed territorially: in the north there were more Catholic Christians who were not so influenced by the Ottoman Empire, and in the south Orthodox also predominated because of the border with Greece. On 28 November 1912 the Albanians, led by Ismail Qemali, finally declared independence.

The international recognition of Albania by the Treaty of London meant the imposition of a Christian monarchy, which led to the outrage of Muslim Albanians, estimated at 80% of the population, and sparked the so-called Islamic revolt. The revolt was led by Essad Pasha Toptani, who declared himself the "saviour of Albania and Islam" and surrounded himself with disgruntled clerics. However, during the period of World War I, Albanian nationalists soon realised that religious differences could lead to the fracturing of the country itself and decided to break ties with the Muslim world in order to have "a common Albania", which led to Albania declaring itself a country without an official religion; this allowed for a government with representation from the four main religious faiths: Sunni, Bektashi, Catholic and Orthodox, training . Albanian secularist elites planned a reform of Islam that was more in line with Albania's traditions in order to further differentiate the country from Turkey, and religious institutions were nationalised. From 1923 onwards, the Albanian National congress eventually implemented the changes from a perspective very similar to that of Western liberalism. The most important reforms were the abolition of the hijab and the outlawing of polygamy, and a different form of prayer was implemented to replace the Salat ritual. But the biggest change was the replacement of Sharia law with Western-style laws.

During World War II Albania was occupied by fascist Italy and in 1944 a communist regime was imposed under the leadership of Enver Hoxha. This communist regime saw the various religious beliefs in the country as a danger to the security of the authoritarian government, and therefore declared Albania the first officially atheist state and proposed the persecution of various religious practices. Thus repressive laws were imposed that prevented people from professing the Catholic or Orthodox faiths, and forbade Muslims from reading or possessing the Koran. In 1967 the government demolished as many as 2,169 religious buildings and converted the rest into public buildings. Of 1,127 buildings that had any connection to Islam at the time, only about 50 remain today, and in very poor condition.[11]. It is believed that the impact of this persecution subject was reflected in the increase of non-believers within the Albanian population. Between 1991 and 1992 a series of protests brought the regime to an end. In this new democratic Albania, Islam was once again the predominant religion, but the preference was to maintain the non-denominational nature of the state in order to ensure harmony between different faiths.

Influences from the international arena

Taking into account this reality of Albania as a country with a majority Islamic population, we turn to the impact of its accession to the EU and the extent to which the values of the two contradict each other.

To begin with, if all this is analysed from a perspective based on the theory of "constructivism", such as that of Helen Bull's proposal , it can be seen how Albania from the beginning of its history has been a territory whose social structure has been strongly influenced by the interaction of different international actors. During the years when it was part of the Byzantine Empire, it largely absorbed Orthodox values; when it was occupied by the Ottomans, most of its population adopted the Islamic religion. Similarly, during the de-Ottomanisation of the Balkans, the country adopted currents of political thought such as liberalism due to the influence of Western European powers. This led to a desire to create a constitutionalist and parliamentary government whose vision of politics was not based on any religious morality.[12]. It can also be seen that the communist regime was imposed in a context common to that of the other Eastern European states. At the same time, it also returned to a democratic path after the collapse of the USSR, even though Albania had not maintained good relations with the Warsaw Pact since 1961.

Since Albania's EU candidacy, these liberal values have been strengthened again. In particular, Albania is striving to improve its infrastructure and to eradicate corruption and organised crime. So it can be seen that Albanian society is always adapting to being part of a supra-governmental organisation. This is an important aspect because it means that the country is most likely to actively participate in the proposals made by the European Commission, without being driven by domestic social values. However, this in turn gives a point in favour of those MEPs who argued that the veto decision was a historic mistake. For if it does not alienate the EU, Albania could alienate other international actors. According to MEPs themselves, these could be Russia or China.

However, there are two limitations to this assertion. The first is that since 2012 Albania has been a member of NATO, so it is already partly alienated from the West in military terms. But a second aspect is more important, namely that Albania already tried during the Cold War to alienate itself from Russia and China, but found that this had negative effects as it made it a satellite state. On the other hand, and this is where Islamic values come into play, Albania today is a member of Islamic organisations such as the OIC (Organisation of Islamic Cooperation). Rejection by the EU could therefore mean Albania's realignment with other Islamic states, such as the Arabs or Turkey. Turkey's own government, currently led by Erdogan's party, has a neo-Ottomanist nature: it seeks to bring the states that formerly constituted the Ottoman Empire under its influence. Albania is being influenced by this neo-Ottomanism and a European rejection could bring it back into the fold of this conception.[13]. Moreover, by moving closer to Middle Eastern Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia, Albania would run the risk of assimilating the Islamic values of these territories.[14]These are incompatible with those of the EU because they do not comply with many of the articles signed up to in the 1952 Universal Declaration of Rights.

Islam and the European Union

Another aspect would be to ask in what respects do Islamic values contradict those of the EU? The EU generally claims to be against polygamy, homophobia or religious practices that oppose the dignity of the person. This has generated, among other things, a powerful internal discussion as to whether the hijab can be considered as a internship staff that should not be legally prevented. Many feminist groups are against this aspect as they relate it to family patriarchalism.[15]However, other EU groups claim that this is only a fully respectable individual internship staff and that its abolition would be a gesture of an Islamophobic nature. In any case, as mentioned above, Albania abolished both polygamy and the wearing of the hijab in 1923 as not reflecting the values of Islam in Albania.[16]. In this respect, it can be observed that although Albania is a country with an Islamic majority, this Islam is much more influenced by Europeanist currents than by Eastern ones: that is, an Islam adapted to European customs and whose values are currently more similar to those of the neighbouring Balkan states.

Some MEPs, usually from far-right groups such as Ressamblement National or Alternativ für Deutschland, claim that Islamic values will never be compatible with European values because they are expansionist and radical. Dutchman Geert Wilders claims that the Koran "is more anti-Semitic than Mein Kampf".[17]. In other words, they claim that those who profess Islam are incapable of maintaining good relations with other faiths because the Koran itself speaks of waging war against the infidel through Jihad. As an example, they cite the terrorist attacks that the Islamist group DAESH has provoked over the last decade, such as those perpetrated in Paris and Barcelona.[18]. But these groups should be reminded that a sacred text such as the Koran can be interpreted in many ways and that although some Muslim groups believe in this incompatibility of good relations with those who think differently, the majority of Muslims interpret the Koran in a very different way, just as they do the Bible, even if some very specific groups become irrational.

This is clearly the case in Albania, where since its democratisation in 1991 there has been a national project integrating all citizens, regardless of their different beliefs. Rather, throughout its history as an independent country there has been only one period of religious persecution in Albania, and that was due to the repression of communist authoritarianism. One limitation in this respect might be the Islamic revolution that took place in Albania in 1912. But it is worth noting that this revolution, despite its strong Islamic sentiment, served to overthrow a puppet government; no law was enforced after it to impose Islamic values on the rest. So it is worth noting that Albania's political model is very similar to that of Rawls in his book "Political Liberalism", because it configures a state with multiple values (although there is a predominant one), but its laws are not written on the basis of any of them, but on the basis of common values among all of them based on reason.[19]. This model proposed by Rawls is one of the founding instructions of the European Union and Albania would be a state that would exemplify these same values.[20]. This is what the Supreme Pontiff Francis I said at his visit in Tirana in 2014: "Albania demonstrates that peaceful coexistence between citizens belonging to different religions is a path that can be followed in a concrete way and that produces harmony and liberates the best forces and creativity of an entire people, transforming simple coexistence into true partnership and fraternity".[21].

Conclusions

It can be concluded that Albania's values as an Islamic-majority state do not appear to be divergent from those of Western Europe and thus the European Union. Albania is a non-denominational state that respects all religious beliefs and encourages all individuals, regardless of their faith, to participate in the political life of the country (which has much merit given the significant religious diversity that has distinguished Albania throughout its history). Moreover, Islam in Albania is very different from other regions due to the impact of European influence in the region. Not only that, but the country also seems very willing to collaborate on common projects. The only thing that, in terms of values, would make Albania unsuitable for EU membership would be if, just as it has been influenced by the actors that have interacted with it throughout its history, it were to be influenced again by Muslim states with values divergent from European ones. But this is more likely to be the case if the EU were to reject Albania, as it would seek the support of other allies in the international arena.

The implications of the accession of the first Muslim-majority state to the EU would certainly be advantageous, as it would encourage a variety of religious thought within the Union and this could lead to greater understanding between the different faiths within it. There would be the possibility of a greater presence of Sunni MEPs in the European Parliament and it would help to enhance coexistence within other EU states on the basis of what has been done in Albania, such as in France, where 10 per cent of the population is Muslim. It should also be said that Albania's exemplary multi-religious behaviour would seriously weaken Euroscepticism and also help to foster harmony within the Balkan region. As Donald Tusk has argued, the Balkans must be given a European perspective and it is in the EU's best interest that Albania becomes part of it.

[1] Lazaro, Ana; European Parliament adopts resolution against veto on North Macedonia and Albania; euronews. ; last update: 24/10/2019

[2] Sputnik World; The West's attitude to the spectre of 'Greater Albania' worries Moscow; Sputnik World, 22/02/2018. grade Sputnik World: Care should be taken when analysing this source as it is often used as a method of Russian propaganda.

[3] "Third Opinion on Albania adopted on 23 November 2011". Strasbourg. 4 June 2012.

[4] Vickers, Miranda (2011). The Albanians: a modern history. London: IB Tauris.

[5] Esposito, John; Yavuz, M. Hakan (2003). Turkish Islam and the secular state: The Gülen movement. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press

[6] Gawrych, George (2006). The crescent and the eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874-1913. London: IB Tauris.

[7] Karpat, Kemal (2001). The politicization of Islam: reconstructing identity, state, faith, and community in the late Ottoman state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[8] Endresen, Cecilie (2011). "Diverging images of the Ottoman legacy in Albania". Berlin: Lit Verlag. pp. 37-52.

[9] Stoppel, Wolfgang (2001). Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien). Cologne: Universität Köln.

[10] Gawrych, George (2006). The crescent and the eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874-1913. London: IB Tauris.

[11] Nurja, Ermal (2012). "The rise and destruction of Ottoman Architecture in Albania: A brief history focused on the mosques". Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

[12] Albanian Constituition of 1998.

[13] Return to Instability: How migration and great power politics threaten the Western Balkans. European Council on Foreign Relations. 2015.

[14] Bishku, Michael (2013). "Albania and the Middle East.

[15] García Aller, Marta; Feminists against the hijab: "Europe is falling into the Islamist trap with the veil".

[16] Jazexhi, Olsi (2014)."Albania." In Nielsen, Jørgen; Akgönül, Samim; Alibašić, Ahmet; Racius, Egdunas (eds.) Yearbook of Muslims in Europe: Volume 6. Leiden: Brill.

[17] EFE; The Dutch MP who compared the Koran to 'Mein Kampf' does not withdraw his words. La Vanguardia; 04/10/2010

[18] Khader, Bichara; Muslims in Europe, the construction of a "problem"; OpenMind BBVA

[19] Rawls, John; Political Liberalism; Columbia University Press, New York.

[20] Kristeva, Julia; Homo europaeus: is there a European culture; OpenMind BBVA.

[21] Vera, Jarlison; Albania: Pope highlights the partnership between Catholics, Orthodox and Muslims; Acaprensa

![A woman crosses a bridge in a rural area of Pakistan [Pixabay]. A woman crosses a bridge in a rural area of Pakistan [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-report-blog.jpg)

▲ A woman crosses a bridge in a rural area of Pakistan [Pixabay].

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS REPORT / Naiara Goñi, Roberto Ramírez, Albert Vidal

Download the document [pdf. 1,4MB] [pdf. 1,4MB

Download the document [pdf. 1,4MB] [pdf. 1,4MB

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The purpose of this strategic analysis report is to ascertain how geopolitical dynamics in and around Pakistan will evolve in the next few years.

Pakistani relations with the US will become increasingly transactional after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. As the US-India partnership strengthens to face China, the US will lose interest in Pakistan and their priorities will further diverge. In response, Beijing will remain Islamabad's all-weather strategic partner despite claims that the debt-trap could become a hurdle. Trade relations with the EU will continue to expand and Brussels will not use trade leverage to obtain Human Rights concessions from Islamabad. Cooperation in other areas will stagnate, and the EU's neutrality on the Kashmir issue will remain unchanged.

In Central Asia, Islamabad will maintain positive relations with the Central Asian Republics, which will be based on increasing connectivity, trade and energy partnerships, although these may be endangered by instability in Afghanistan. Relations with Bangladesh will remain unpropitious. An American withdrawal from Afghanistan will most likely lead to an intensification of the conflict. Thanks to connections with the Taliban, Pakistan might become Afghanistan's kingmaker. Even if regional powers like Russia and China may welcome the US withdrawal, they will be negatively affected by the subsequent security vacuum. Despite Pakistani efforts to maintain good ties with both Iran and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), if tensions escalate Islamabad will side with Riyadh. Pakistan's weak non-proliferation credentials will be coupled with a risk of Pakistan sharing its nuclear arsenal with the Saudis.

A high degree of tensions will continue characterising its relations with India, following the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A of the Indian constitution. Water scarcity will be another source of problems in their shared borders, which will be exacerbated by New Delhi's construction of reservoirs in its territory. Islamabad will continue calling for an internationalization of the Kashmir issue, in search of international support. They are likely to fight localised skirmishes, but there is a growing fear that the contentious issues mentioned above could eventually lead to an all-out nuclear war. PM Khan and Modi will be reluctant to establish channels of rapprochement, partly due to internal dynamics of both countries, be it Hindu nationalism or radical Islam.

A glance inside Pakistan will show how terrorism will continue to be a significant threat for Pakistan. As a result of Pakistan's lack of effective control in certain areas of its territory, the country has been used as a base of operations by terrorist and criminal groups for decades, to perpetrate all kinds of attacks and illegal activities, which will not change in the near future. Risks that should be followed closely include the power of anti-Western narratives wielded by radical Islamists, the lack of a proper educational system and an ambiguous counter-terrorism effort. In the midst of this hodgepodge, religion will continue to have a central role and will undoubtedly be used by non-state actors to justify their violent actions, although it is less likely that it will become an instrument for states to further their radical agendas.

Albania and North Macedonia are forced to accept tougher negotiating rules, while Serbia and Montenegro reassess their options.

Brexit has been absorbing the EU's negotiating attention for many months and now Covid-19 has slowed down non-priority decision-making processes. In October 2019, the EU decided to cool down talks with the Western Balkans, under pressure from France and some other countries. Albania and North Macedonia, which had made the work that Brussels had requested in order to formally open negotiations, have seen the rules of the game changed just before the start of the game.

![meeting of the Western Balkans with EU countries, held in London in 2018 [European Commission]. meeting of the Western Balkans with EU countries, held in London in 2018 [European Commission].](/documents/10174/16849987/ue-balcanes-blog.jpg)

▲ meeting of the Western Balkans with EU countries, held in London in 2018 [European Commission].

article / Elena López-Doriga

Since its origins, the European Community has been evolving and expanding its competences through treaties structuring its functioning and aims. issue The membership of the organisation has also expanded considerably: it started with 6 countries (France, Belgium, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) and now consists of 27 (following the recent departure of the United Kingdom).

The most notable year of this enlargement was 2004, when the EU committed itself to integrating 10 new countries, which was a major milestone challenge, given that these countries were mainly from Central and Eastern Europe, coming from the "iron curtain", with less developed economies emerging from communist systems and Soviet influence.

The next enlargement round goal is the possible EU membership of the countries of the Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia). However, at a summit held in Brussels at the end of 2019 to open accession negotiations for new members, some EU countries were against continuing the process, so for the time being the accession of the candidate countries will have to wait. Some EU leaders have called this postponement a "historic mistake".

Enlargement towards Central and Eastern Europe

In May 1999 the EU launched the Stabilisation Process and association. The Union undertook to develop new contractual relations with Central and Eastern European countries that expressed a desire to join the Union through stabilisation agreements and association, in exchange for commitments on political, economic, trade or human rights reform. As a result, in 2004 the EU integrated the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia (the first member from the Western Balkans). In 2007 Bulgaria and Romania also joined the Union and in 2013 Croatia, the second Western Balkan country to join.

The integration of the Western Balkans

Since the end of the Yugoslav wars in late 2001, the EU has played a very prominent role in the Balkans, not only as an economic power in subject reconstruction, but also as a guarantor of stability and security in the region. The EU's goal is in part to prevent the Western Balkans from becoming a security black hole, given the rise of rising nationalism, growing tension between Moscow and Washington, which fuels tensions between ethnic groups in the region, and China's economic penetration of the area. Clearer progress towards Balkan integration was reaffirmed in the Commission's Western Balkans strategy of February 2018 and in the Sofia Declaration following the EU-Western Balkans Summit held in the Bulgarian capital on 17 May 2018. At the Summit, EU leaders reiterated their unequivocal support for the European perspective of the Western Balkans. "I see no future for the Western Balkans other than the EU. There is no alternative, there is no plan B. The Western Balkans are part of Europe and belong to our community," said the then president of the European committee , Donald Tusk.

Official candidates: Albania and Macedonia

Albania applied for EU membership on 28 April 2009. In 2012, the Commission noted significant progress and recommended that Albania be granted the status of candidate, subject to the implementation of a number of outstanding reforms. In October 2013, the Commission unequivocally recommended that Albania be granted membership status candidate . visit Angela Merkel visited Tirana on 8 July 2015 and stated that the prospect of the Balkan region's accession to the European Union (EU) was important for peace and stability. He stressed that in the case of Albania the pace of the accession process depended on the completion of reforms in the judicial system and the fight against corruption and organised crime. In view of the country's progress, the Commission recommended the opening of accession negotiations with Albania in its 2016 and 2018 reports.

On the other hand, the Republic of North Macedonia (former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia) applied for EU membership in March 2004 and was granted country status candidate in December 2005. However, the country did not start accession negotiations because of the dispute with Greece over the use of the name "Macedonia". When this was successfully resolved by the agreement of Prespa under the country's new name - Northern Macedonia - the committee agreed on the possibility of opening accession negotiations with this country in June 2019, assuming the necessary conditions were met.

Potential candidates: Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a potential candidate country. Although it negotiated and signed a Stabilisationagreement and association with the EU in 2008, the entrance entry into force of this agreement remained at Fail mainly due to the country's failure to implement a judgement core topic of the European Court of Human Rights. In the meantime, the Parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina has not reached a agreement concerning the rules of procedure governing its meetings with the European Parliament (twice a year), as these meetings have not been held since November 2015, and this status constitutes a breach of agreement by Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Kosovo is a potential candidate candidate for EU membership. It declared its independence unilaterally in February 2008. All but five Member States (Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia, Spain and Cyprus) have recognised Kosovo's independence. Among the countries in the region, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina have also failed to recognise Kosovo as an independent state. In September 2018, the European Parliament went a step further and decided to open inter-institutional negotiations, which are currently underway. However, the fact that not all member states currently recognise its independence is a major stumbling block.

Negotiating accession: Montenegro and Serbia

Montenegro, one of the smallest states on the European continent, has been part of different empires and states over the past centuries, finally gaining independence peacefully in 2006. It applied to join the Union in December 2008; it was granted the status of a country candidate in December 2010, and accession negotiations started in June 2012. By the end of 2018, 32 negotiating chapters had been opened, out of a total of 35.

Serbia 's process began in December 2009 when former president Boris Tadić officially submitted application for membership and also handed over to justice war criminal Ratko Mladić, manager of the Srebrenica massacre during the Bosnian War, who was hiding on Serbian territory. However, the conflict with Kosovo is one of Serbia's main obstacles to EU accession. It was granted country status candidate in March 2012, after Belgrade and Pristina reached an agreement agreement on Kosovo's regional representation. The official opening of accession negotiations took place on 21 January 2014. In February 2018, the Commission published a new strategy for the Western Balkans stating that Serbia (as well as Montenegro) could join the EU by 2025, while acknowledging the "extremely ambitious" nature of this prospect. Serbia's future EU membership, like that of Kosovo, remains closely linked to the high-level dialogue between Serbia and Kosovo under EU auspices, which should lead to a legally binding comprehensive agreement on the normalisation of their relations.

A step back in the negotiations

In October 2019, a summit was held in Brussels, goal to structure the negotiations of the official candidates for EU membership. Both North Macedonia and Albania were convinced that a date would be set to start the long process of negotiations. However, the process reached a stalemate after seven hours of wrangling, with France rejecting both countries' entrance . France led the campaign against enlargement, but Denmark and the Netherlands also joined the veto. They argue that the EU is not ready to take on new members. "It doesn't work too well at 28, it doesn't work too well at 27, and I'm not sure it will work any better with another enlargement. So we have to be realistic. Before enlarging, we need to reform ourselves," said French President Emmanuel Macron.

The then president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, considered the suspension to be a major historic mistake and hoped that it would only be temporary. For his part, Donald Tusk said he was "ashamed" of the decision, and concluded that North Macedonia and Albania were not to blame for the status created, as the European Commission's reports were clear that both had done what was necessary to start negotiations with the EU.

In Albania, Prime Minister Edi Rama said that the lack of consensus among European leaders would not change Albania's future EU membership aspirations. He asserted that his government was determined to push ahead with the reforms initiated in the electoral, judicial and administrative spheres because it considered them necessary for the country's development , not just because Brussels demanded it.

In North Macedonia, on the other hand, the European rejection was deeply disappointing, as the country had proceeded to reform its institutions and judicial system and fight corruption; it had also changed its constitution, its name and its national identity. The rejection left the country, candidate official status for the past 14 years, in a state of great uncertainty, and Prime Minister Zoran Zaev decided to dissolve parliament and call elections for 12 April 2020 (later postponed due to the Covid-19 emergency). "We have fulfilled our obligations, but the EU has not. We are the victims of a historic mistake that has led to a huge disappointment," Zaev said.

A new, stricter process

Despite the fact that, according to the Commission, North Macedonia and Albania fulfilled the requirements criteria to become accession candidates, Macron proposed to tighten the accession process. In order to unblock status and continue with the process, which the EU claims to be a priority goal , Brussels has given in to the French president's request by establishing a new methodology for integrating new countries.

The new process envisages the possibility of reopening chapters of the negotiations that were considered closed or of fail the talks underway in one of the chapters; it even envisages paralysing the negotiations as a whole. It aims to give more weight to governments and to facilitate the suspension of pre-accession funds or the freezing of the process if candidate countries freeze or reverse committed reforms. The new method will apply to Albania and North Macedonia, whose negotiations with the EU have not yet begun, while Serbia and Montenegro will be able to choose whether to join, without having to change their established negotiating framework , according to the Commission.

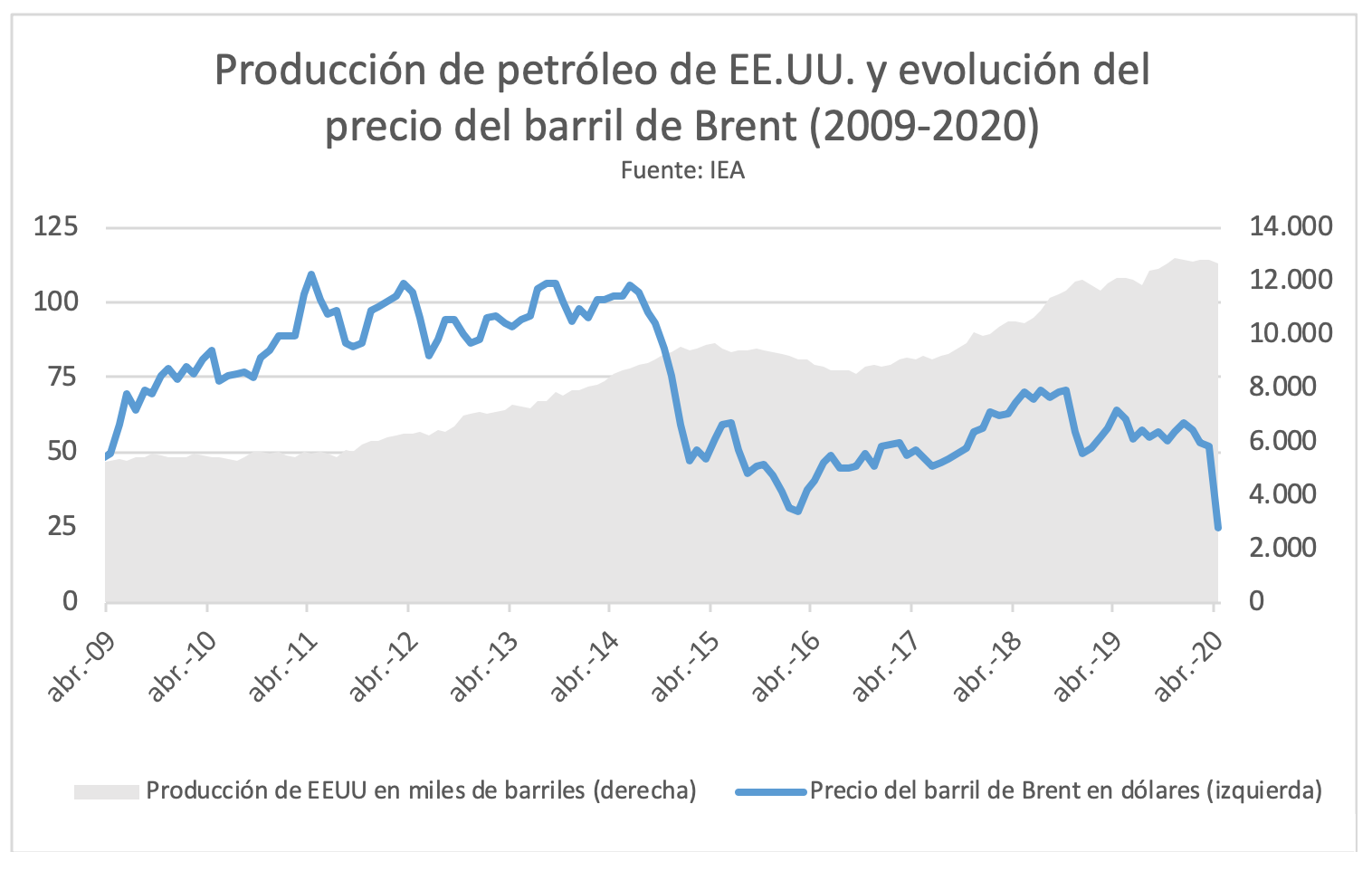

March and April 2020 will be remembered in the oil industry as the months in which the perfect storm occurred: a drop of more than 20% in world demand at the same time as a price war was unleashed that increased the supply of crude oil, generating an unprecedented status of abundance. This status has highlighted the end of OPEC's dominance over the rest of the oil producers and consumers after almost half a century.

![Pumping structure in a shale oil field [Pixabay]. Pumping structure in a shale oil field [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/precio-petroleo-blog.jpg)

▲ Pumping structure in a shale oil field [Pixabay].

ANALYSIS / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa

On 8 March, in view of the failure of the so-called group OPEC+ negotiations, Saudi Arabia offered its crude oil at a discount of between 6 and 8 dollars on the international market while announcing an increase in production from 1 April to a record 12 million barrels per day. The Saudi move was imitated by other producers such as Russia, which announced an increase of 500,000 barrels per day (bpd) from the same date, when the cartel's previous agreements expire. The reaction of the markets was immediate, with a historic drop in prices of more than 30% in all international indices and the opening of headlines announcing the start of a new price war. The oil world was stunned by the collapse in the price of crude oil, which reached historic lows on 30 March, with the price of a barrel of WTI dropping below 20 dollars, a psychological barrier that demonstrated the harshness of the confrontation and the historic consequences it could have for a sector of particular geopolitical sensitivity.

Previous experiences

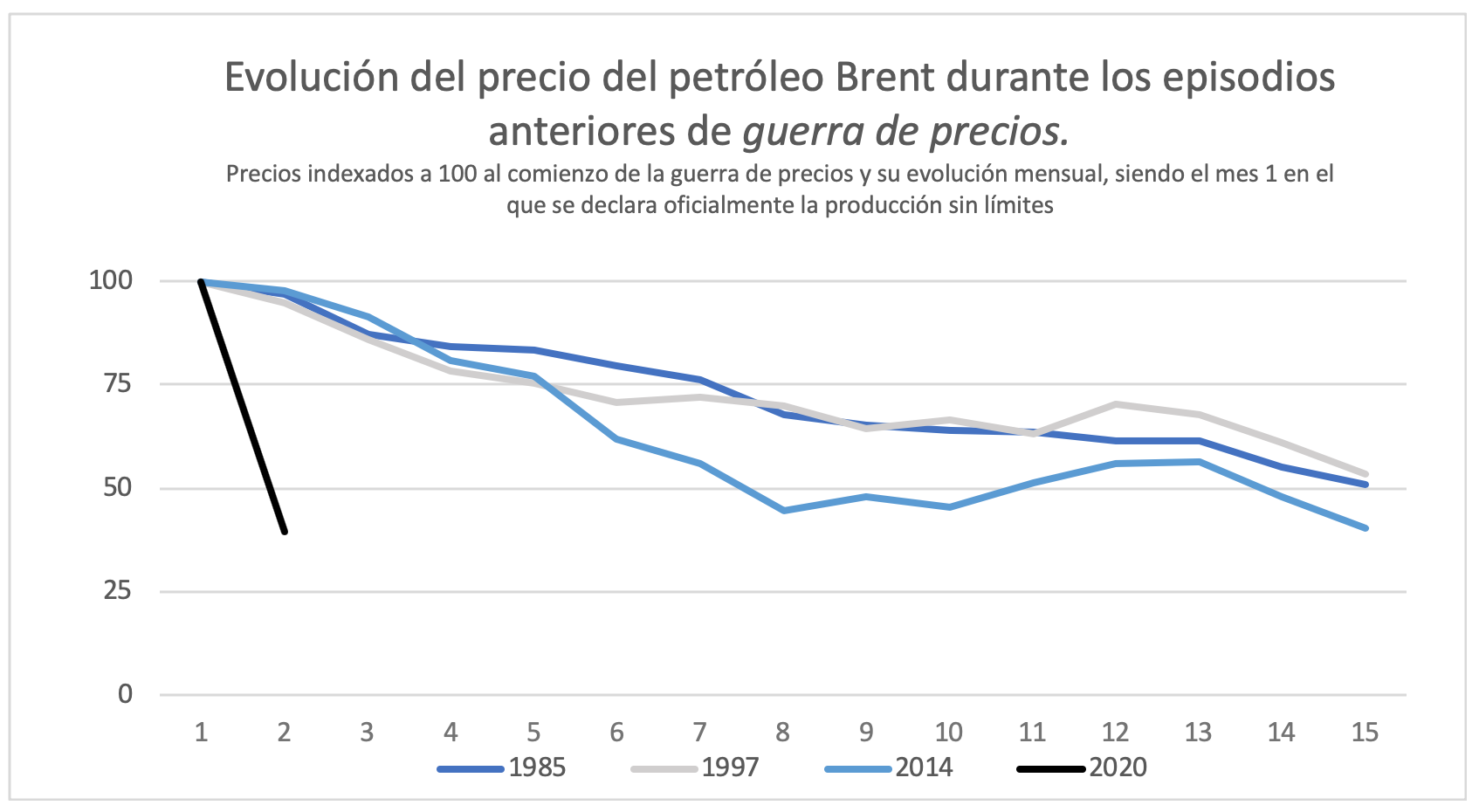

Saudi Arabia, the world leader in the oil industry because of its vast reserves and huge, export-oriented production, has resorted three times to a price war to obtain commitments from other producers to make supply cuts to stabilise international prices. The oil market, accustomed to an artificially high price, tends to suffer dramatic price declines when supply is unrestricted available . committee Due to the economic and political instability that these prices generate in the producing countries, they usually return quickly to the negotiating table, where Saudi Arabia and its partners in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) always await them.

The first experience of this subject took place in 1985, after the Iran-Iraq war and the oil crisis of the 1970s, Saudi King Fahd bin Abdulaziz Al Saud took the decision to increase production unilaterally in order to recover the market share he had lost to the emergence of new producing regions such as the North Sea or the Gulf of Mexico. The experience led to a 50% drop in prices after more than a year of unrestricted production, which ended with a agreement in December 1986 by 12 OPEC countries to make the cuts demanded by Saudi Arabia and its allies.

In 1997, in response to Saudi Arabia's concern over the increasing displacement of its oil from US refineries in favour of Venezuelan and Mexican crude, the newly arrived Saudi monarch Abdullah bin Abdulaziz decided to announce in the midst of an OPEC summit in Jakarta that he would proceed to increase production without restrictions. The Saudi strategy did not count on the fact that the following year an economic crisis would break out among emerging markets with particular virulence in Southeast Asia and Russia, which plunged prices by 50% again until a new agreement was reached in April 1999.

With the 21st century, came the oil bonanza with the so-called commodity super cycle (2000-2014) that kept oil prices at unknown levels above 100 dollars between 2008 and 2010-2014. This bonanza made it possible to increase investment in exploration and production, generating new extraction techniques that were previously unknown or simply economically unfeasible. In 2005, the US was experiencing a worrying oil crisis, with production at an all-time low of only 5.2 million bpd compared to 9.6 million bpd in 1970. Moreover, energy dependence of approximately 6 million bpd was being met by increasingly expensive crude oil imports from the Persian Gulf, which after 9/11 was viewed with greater scepticism, and Venezuela, which already had Hugo Chávez as its political leader. goal High oil prices allowed the recovery of previously frustrated ideas such as hydraulic fracturing, which was given massive permits to be developed from 2005 onwards with the aim of mitigating the country's other major energy crisis: the rapid decline in domestic production of natural gas, a much more expensive and difficult commodity for the US to import. Hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, enabled an unexpected growth in natural gas production, which soon attracted the attention of the US oil sector. By 2008, a variant of fracking could be applied to oil extraction, a technique later called shale, leading to an unprecedented revolution in the United States that increased the country's production by more than 5 million barrels per day in the period 2008-2014. The change in the US energy landscape was such that in 2015 Barack Obama withdrew a 1975 law that prohibited the US from exporting domestically produced oil.

The Saudi reaction was swift, and at OPEC's Vienna headquarters in November 2014, it launched a new campaign of unrestricted production that would allow the Kingdom to recover part of its market share. The effects on international markets were more dramatic than ever, with a 50% drop in price in just 7 months. Multinational oil companies (IOCs) and national oil companies (NOCs) dramatically reduced their profits and were forced to make cuts not seen since the beginning of the century. Exporting countries also suffered the effects of lower fiscal revenues with many emerging markets plunged into unmanageable fiscal deficits, inflation and even recession, with Venezuela in particular sliding into the socio-economic chaos we know today. To Saudi Arabia's despair, the US shale industry showed unexpected resilience by maintaining production at 4 million barrels per day for 2016 from a peak of 5 million in 2014. Saudi Arabia did not understand that shale oil, unlike conventional oil, was not a mature industry, but an expanding one and development. US producers managed to increase the oil recovery rate from 5% to 12% between 2008-2016, the equivalent of increasing productivity by 2.4 times. In addition, the elimination of less competitive companies allowed for a reduction in the cost of services and easier access to transportation infrastructure. The nature of shale, with wells maturing in 18 months to 3 years, compared to 30 years or more for a conventional well, allowed production to be shut in for a short enough period of time to minimise the impact of lower prices, opting to keep the most competitive wells. Saudi Arabia gave up and opted for a 180 degree turnaround Degrees in its strategy, although it did manage to bring Russia to the negotiating table. The longest price war in history, after almost 22 months, ended with an unprecedented agreement among OPEC countries with the incorporation of Russia and its sphere of energy influence, group known as OPEC+. A Russia wounded by international sanctions and the weakness of its currency had given in to Saudi Arabia, which, however, had not managed to defeat the US shale oil revolution.

North American shale production has not stopped growing, and despite its effectiveness, it is the only region in the world with a similar industry, growing at a rate of more than one million barrels per day per year. This status has provided the US with robust energy security as it is not dependent on imports of Venezuelan or Gulf crude. The country achieved positive net oil exports at the end of 2019 for the first time in more than half a century, in addition to being a net exporter of natural gas, coal and refined products. Much of the Trump administration's geostrategic retreat in the Middle East is a response to the country's growing energy independence, which reduces its interests in the region.

The breakdown of group OPEC+:

As mentioned, during the first week of March, OPEC+ met in Vienna seeking a agreement for a further cut of some 1.8 million barrels per day to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in China. The unease among producers was evident, having executed a similar cut in December 2019. Saudi Arabia was trying to share out as much of the production cuts as possible when Russian energy minister Alexander Novak said "niet", citing economic solvency for a drop in prices, scuppering any subject from agreement. It is not known whether Russia's refusal was the result of a well-thought-out plan or simply a bluff to gain ground in the negotiations, but it was the beginning of a new price war. As can be seen in the graph below, the drop in the price of crude oil in the first month has been historic, without a similar reference letter in the history of negotiations between producers. The increase in the availability of oil in the markets due to the Saudi strategy of loading tankers with crude from its strategic reserves, together with a dry stop of the Economics and the demand for oil, generated a sudden price depression hitherto unknown in the sector. Previous price wars normally had the stabilising element that the lower the price of oil products, the higher the consumption in the short term deadline. However, due to the economic effects of the quarantine, this market counterweight disappears, generating in one month what would otherwise have taken 12 to 15 months.

The effects of COVID-19 on global oil demand are estimated to have fallen by 12.5% in March and are expected to reach 20% in April. In the areas of Europe most affected by the quarantine, the drop in fuel sales at service stations has reached 75%, a figure that is very likely to be replicated in the rest of the advanced economies as the measures are tightened and which China is already beginning to leave behind after two months of confinement. The case of air transport is particular, as it consumes 16 million bpd and is currently totally suspended, with no clear date for a return to normality in international aviation. The partial stoppage of industrial production, the extent of which is still unknown, could lead to even greater drops in consumption. Such a status would not require increased production to generate a collapse in prices, which with the added pressure on the supply side are generating unprecedented levels of stress on storage, transport and refining capacity.

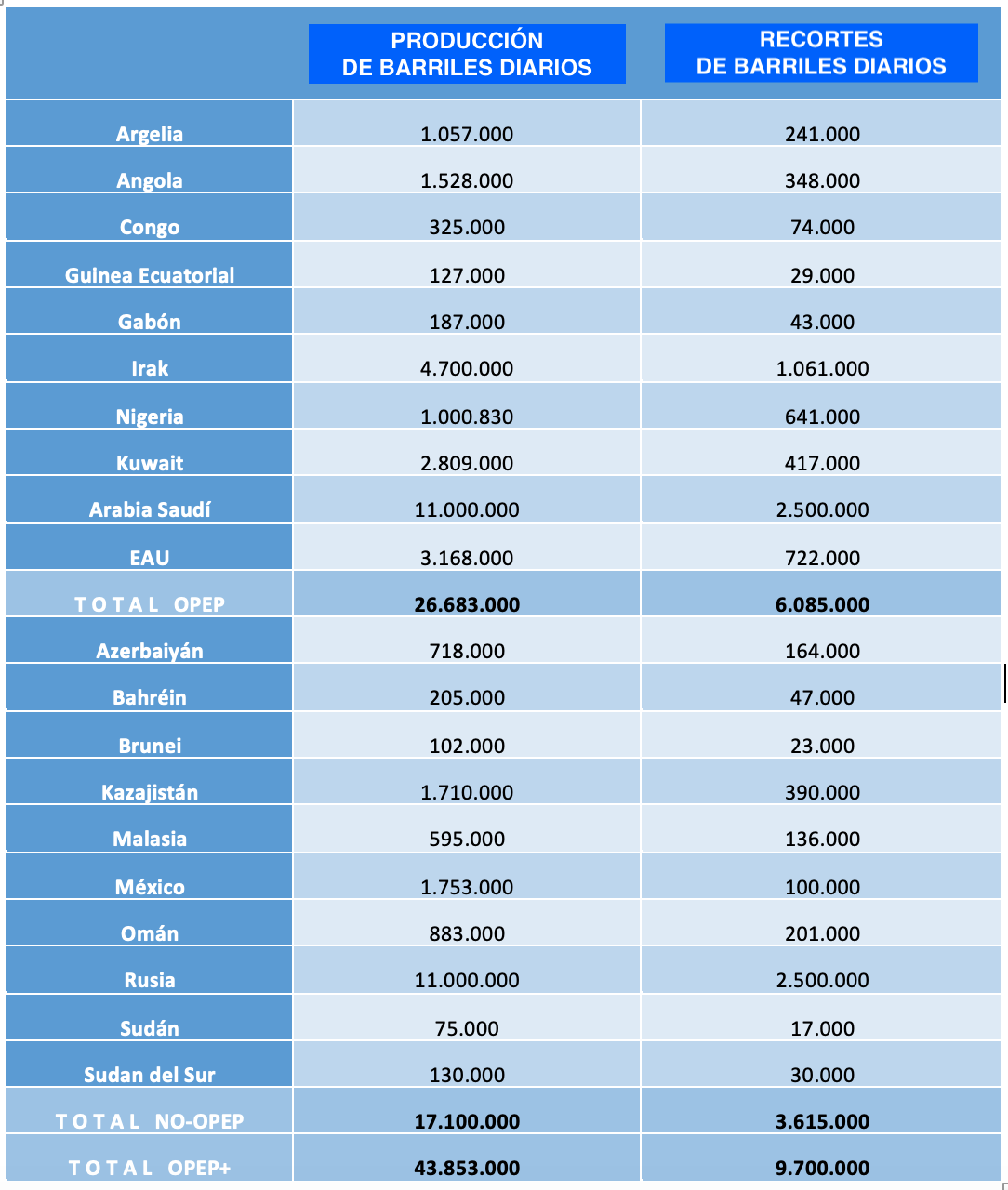

A historic agreement :

In early April, Donald Trump, fearful that an oil glut could further depress prices and destroy the US hydrocarbon industry, took the initiative to speak by telephone with the leaders of Saudi Arabia and Russia. In a paradoxical move, the US President succeeded in bringing the major producers closer together to establish new cuts that would put an end to the price war. On 9 April, after several weeks of speculation, the largest ever producers' meeting took place at group , including OPEC members and 10 non-member countries among which Russia, Kazakhstan and Mexico stood out. After several days of negotiations, it was agreed to cut production by 23% in 20 countries with a combined output of more than 40 million barrels, leaving almost 10 million barrels out of the market, starting on the first day of May. The negotiations were coordinated by OPEC and the G20, which at the time was chaired by Saudi Arabia. In this way, a picturesque agreement was reached whereby the aforementioned 10 million barrels were reduced among the OPEC+ members, included in the table below, and another 5 million barrels were estimated to be reduced in an unspecified manner among the US, Canada, Brazil and Norway. The latter cuts, by the nature of their sectors, would be made through the free market and it remains to be seen how they will materialise.

There is some scepticism in the industry and markets about the effectiveness of these cuts, which amount to 10-15% of the oil consumed globally before the COVID-19 crisis. Consumption has fallen by around 20% and oil storage capacity is starting to run out, reducing the margin for absorbing surplus oil. In addition, the cuts will start to be implemented on 1 May, leaving a three-week window that could further depress prices. The nature of agreement, which is voluntary and difficult to monitor, leaves the door open to non-compliance with the established cuts, which are often difficult to apply due to the geological conditions of certain old wells or the existence of contracts that require financial compensation if supply is interrupted. In general, the level of compliance with OPEC agreements has been low, with a greater incidence in countries that export by sea and a lesser incidence in those that export by pipeline, which, unlike maritime cargoes, cannot be controlled by satellite.

The main actors:

Saudi Arabia:

Amid the wreckage of the OPEC+ negotiations, on 6 March Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) led a new palace coup in which former heir to the Saudi throne Mohammed bin Nayef and other members of the royal family were arrested and charged with plotting against Crown Prince MBS and his father Salman bin Abdulaziz. All this at a time when the heir to the Saudi throne seemed to want to consolidate his power with a risky new strategy after the utter failure of the Yemen War and the Vision 2030 national modernisation plan.

Saudi Arabia's undisputed leadership in driving the oil market is based on its ability to increase production by several million barrels in less than six months, something no other country in the world is able to do. The increase in production also allows Saudi Arabia to partially compensate for the decline in prices per barrel, which together with its foreign exchange reserves and access to cheap credit allows Saudi Arabia to face a price war with an apparent resilience far superior to that of any other OPEC country. The low cost of producing a barrel of oil in the country, at around $7, also allows it to maintain revenues in almost any market environment.

However, foreign exchange reserves, at $500 billion, are 30% lower than in 2016, and may be insufficient to maintain dollar-rial parity for more than two years without oil revenues, which is essential for a society accustomed to import-dependent opulence. Moreover, the fiscal deficit has been a major problem for the country, which has been unable to reduce it below 4% after reaching a peak of 16% in 2016 as result of an insufficient recovery in oil prices and the costs of the war in Yemen. Oil's energy dominance has an expiry date and Saudi Arabia's finances are addicted to an activity that accounts for 42% of its GDP and generates 87% of tax revenues. For the moment, the Saudi minister of Economics has already announced a 5% cut in budget by 2020, sample , agreement oil does not ensure an optimistic scenario. In any case, Saudi Arabia has been one of the big winners in the price war. In the failed March negotiations, Saudi Arabia produced 9.7 million barrels per day, a figure that had risen to 11 million barrels per day in the April negotiations. As the cuts are set on a proportional basis, in just one month the Saudi kingdom gained 1.3 million barrels of market share. Similarly, the Saudi sovereign wealth fund Petroleum Investment Fund (PIF) bought shares in Eni, Total, Equinor, Shell and Repsol during the month of April, in a context of stock market falls in these companies.

Russian Federation:

Russia stood firm at the start of the price war, highlighting the resilience of the Russian energy sector and the volume of the country's sovereign reserves, which are lower than those of Saudi Arabia but amount to 435 billion dollars and a stabilisation fund of another 100 billion: 33% more than in 2014. Paradoxically, international sanctions on the Russian oil sector have reduced its dependence on the outside world, allowing the devaluation of the freely convertible rouble not to affect production and partially compensate for lower prices. Russia' s capacity to increase production in the short term deadline, unlike Saudi Arabia, is less than 500,000 bpd, which leaves Russia unable to compensate lower prices with higher production, the main reason for the country's acceptance of the April negotiations result .

Vladimir Putin's leadership is unquestionable with a possible constitutional reform that would allow for an extension of his term of office delayed due to COVID-19. The Russian political elite's good relations with the oil oligarchy allow for unity of action in a country with greater atomisation and the presence of private capital in its companies. Alexander Novak's strategy seems to be in line with that of Igor Sechin, CEO of Rosneft, who is betting on a context of low prices that will end up deeply damaging the US shale industry. There is speculation about a possible US diplomatic intervention with the Russian government in favour of April's agreement OPEC+. Russia's Rosneft's latest move , abandoning Venezuela by selling all its assets to a Russian government-controlled business , may be one explanation for Moscow's concession to accept a agreement that for a month it tried, at least rhetorically, to avoid. The development of future US sanctions on the Russian oil sector will be a good indicator of this possible agreement.

United States:

For the US, falling oil prices mean one of the biggest tax cuts of all time, in the words of its president, with a price of less than a dollar per gallon. However, the oil industry generates more than 10 million jobs in the US and is a central activity in many states such as Texas, Oklahoma or New Mexico, which are fundamental for a hypothetical Republican victory in the 2020 elections. Moreover, the geostrategic importance of the sector, which has allowed the US to reduce its energy dependence to historic lows, has led Donald Trump to take on the responsibility of safeguarding the US oil industry. He himself coordinated the first steps for a major agreement, by means of pressure, threats and concessions. The truth is that the price crisis has come at a time of certain exhaustion for the sector, which was beginning to suffer the effects of over-indebtedness and pressure from investors to increase profits. Since 2011, North American crude oil, priced on the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) index, has experienced an evaluation 10% lower than that of Brent or the OPEC Basket, the other global indices, generating a hyper-competitive environment that was beginning to take its toll on shale producers, which since the end of 2019 have seen a 20% drop in the total drillingissue year-on-year. The North American market, which had already been experiencing storage and transportation problems since 2017, collapsed in the third week of April with negative prices due to the limitations to store oil and speculation in the futures markets.

Donald Trump has finally secured a global agreement that does not bind the US directly, but leaves it to the market to regulate the cuts that seem more than foreseeable. In this way, the Trump administration allows itself not to have to intervene in the oil market, something that would surely force the development of legislation and a complex discussion to save the polluting oil industry at the taxpayer's expense. From the Senate, several politicians from both parties have tried to introduce the need for tariffs or sanctions on those producers who flood the domestic market to the parliamentary discussion , recovering old initiatives such as the NOPEC Act. These threats have allowed the President to gain a strong position at the international level, being one of the big winners at the agreement OPEC+ in April. In fact, when negotiations seemed on the verge of collapse due to Mexico's refusal to take on 400,000 barrels per day of cuts, the US intervened by announcing that it would be the US that would take them on. Subsequent leaks have shown the existence of financial insurance taken out by Mexico in case of low oil prices, which would be charged per barrel produced. The US intervention, more rhetorical than internship since the country has no concrete production to cut, saved agreement from another failure.

![Facilities for the refining of petroleum products [Pixabay]. Facilities for the refining of petroleum products [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/precio-petroleo-blog-2.jpg)

Facilities for the refining of petroleum products [Pixabay].

Nothing will ever be the same again: