Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label drug trafficking .

The U.S. is keeping an eye on the innovation of methods that could also be used to introduce terrorist cells or even weapons of mass destruction

In the last ten years, the proliferation of submersible and semi-submersible vessels, which are difficult to detect, has accounted for a third of drug transport from South America to the United States. The incorporation of GPS systems by the cartels also hinders the global fight against narcotics. A possible use of these new methods for terrorist purposes keeps the United States on its toes.

▲ Narco-submarine found in the jungle of Ecuador in 2010 [DEA]

article/ Marcelina Kropiwnicka

Drug trafficking to large consumer markets, especially the United States and Europe, is particularly innovative: the magnitude of the business means that attempts are made to overcome any barriers put in place by States to prevent its penetration and distribution. In the case of the United States, where the illicit arrival of narcotics dates back to the 19th century – from opium to marijuana to cocaine – the authorities' continued efforts have succeeded in intercepting many drug shipments, but traffickers are finding new ways and methods to smuggle a significant volume of drugs into the country.

The most disturbing method in the last ten years has been the use of submersible and semi-submersible vessels, commonly referred to as narco-submarines, which allow several tons of substances to be transported – five times more than a fishing boat did – evading the surveillance of the coast guard [1]. Satellite technology has also led traffickers to leave loads of drugs at sea, then picked up by pleasure boats without arousing suspicion. These methods make reference letter recent reports from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Through the waters of Central America

For many years, the usual way to transport drugs out of South America to the United States has been by fishing boats, speedboats, and light aircraft. Advances in airborne detection and tracking techniques have pushed drug traffickers to look for new ways to get their loads north. Hence the development of the narco-submarines, whose issue, since a first interception in 2006 by the US authorities, has seen a rapid progression.

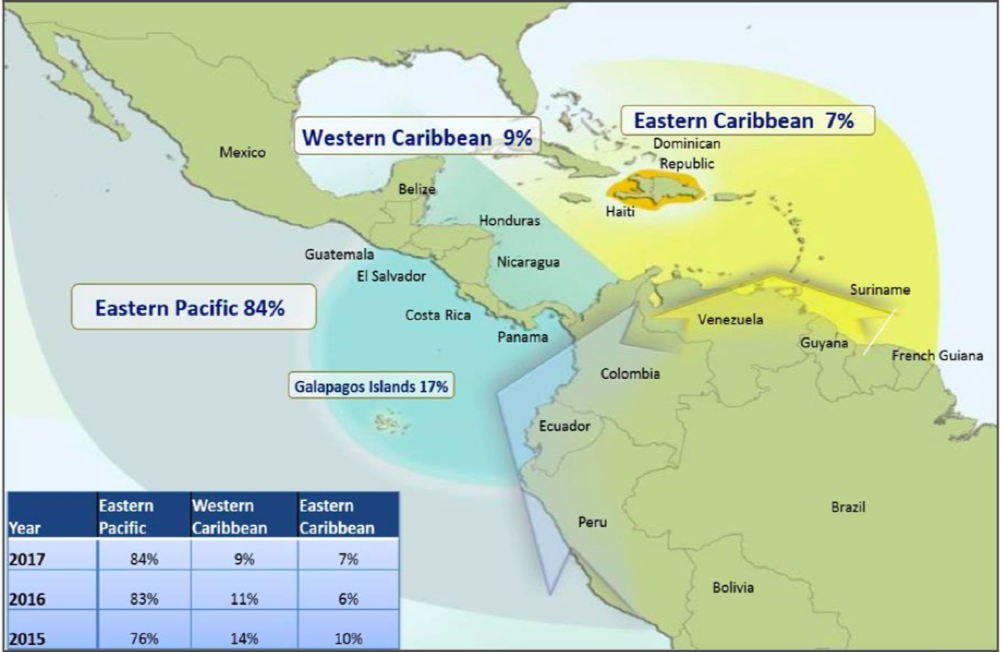

This means of transport is one of the reasons why since 2013 there has been a 10% increase in trafficking on the drug route that goes from Colombia (a country that produces 93% of the cocaine consumed in the United States) to Central America and Mexico, from where the shipments are introduced into the United States. According to the DEA, this corridor now accounts for an estimated 93 percent of the movement of cocaine from South America to North America, compared to 7 percent of the route that seeks the Caribbean islands (mainly the Dominican Republic) to reach Florida or other places along the U.S. coast.

For a while, rumors spread among the U.S. Coast Guard that drug cartels were using narco-submarines. Without having seen any of them so far, the agents gave him the name 'Bigfoot' (as an alleged ape-like animal that would inhabit forests in the US Pacific is known).

The first sighting occurred in November 2006, when a U.S. Coast Guard patrol boat detected a blurred shape in the ocean, about 100 miles off the coast of Costa Rica. When agents approached, they discovered three plastic tubes emerging from the water, which came from a submersible craft that was making its way two meters below the surface. Inside they found three tons of cocaine and four men armed with an AK-47 rifle. The Coast Guard dubbed it 'Bigfoot I'.

Two years later there would be a 'Bigfoot II'. In September 2008, a U.S. Navy Coast Guard frigate seized a similar aircraft 350 miles from the Mexico-Guatemala border. The crew consisted of four men and the cargo was 6.4 tons of cocaine.

By then, U.S. authorities estimated that more than 100 submersibles or semi-submersibles had already been manufactured. In 2009, they estimated that they were only able to stop 14 percent of shipments and that this mode of transport supplied at least a third of the cocaine reaching the U.S. market. The navies of Colombia, Mexico and Guatemala have also seized some of these narco-submarines, which in addition to having been located in the Pacific have also been detected in the Caribbean and the Atlantic. Made by hand in the jungle, perhaps the most striking episode was that of having found one of them in the interior of Ecuador, in the waters of a river.

Its technical innovation has frequently surprised counternarcotics officials. Many of these self-propelled narco-submarines are up to fifteen meters long, made of synthetic materials and fiberglass, and have been designed to reduce radar or infrared detection. There have also been models with GPS navigation systems to be able to refuel and receive food at agreed appointments along the way.

GPS Tracking

The development and the generalization of GPS has also helped drug traffickers to introduce greater innovations. One procedure, for example, has been to fill a torpedo-shaped container – like a submersible, but this time without a crew – with drugs, attached to a buoy and a signal emitter. The container can hold up to seven tons of cocaine and is attached to the bottom of a ship by a cable. If the ship is intercepted, it can simply drop the container deeper, and then be retrieved by another vessel thanks to the satellite locator. This makes it extremely difficult for authorities to capture the drugs and apprehend traffickers.

The GPS navigation system is also used to deposit drug loads at points in U.S. territorial waters, where they can be picked up by pleasure boats or a small number of people. group of people without arousing suspicion. The package containing the cocaine is coated with several layers of material and then waterproofed with a subject foam. The package is placed inside a duffel bag that is deposited on the seabed to be later retrieved by other people.

As indicated by the AED in its report from 2017, "This demonstrates how drug trafficking organizations have evolved their methods of carrying out cocaine transactions using technology." And quotation the example of organizations that "transport kilos of cocaine in waterproof packages to a predetermined location and attach it to the ocean floor to be later removed by other members of the organization who have GPS location," which "allows members of drug trafficking organizations to compartmentalize their work, separating those who do the sea transport from the distributors on land."

|

Cocaine Journey from South America to the United States in 2017 [DEA] |

Terrorist risk

The possibility that these hard-to-detect methods could be used to smuggle weapons or could be part of terrorist operations worries U.S. authorities. Retired Vice Admiral James Stravidis, former head of the U.S. Southern Command, has warned of the potential use of submersibles especially "to transport more than just narcotics: the movement of cash, weapons, violent extremists or, at the worst end of the spectrum, weapons of mass destruction."

This risk was also referred to by Rear Admiral Joseph Nimmich when, as commander of the group South of work A joint Inter-Agency Agency, it faced the rise of submersibles. "If you can transport ten tons of cocaine, you can transport ten tons of anything," he told The New York Times.

According to this newspaper, the stealth production of homemade submarines was first developed in Sri Lanka, where the group Tamil Tiger rebels used them in their confrontation with government forces. "The Tamils will go down in history as the first terrorist organization to develop underwater weapons," Sri Lanka's Defense Ministry said. In 2006, as the NYT states, "a Pakistani and a Srinlancan provided Colombians with blueprints to build semi-submersibles that were fast, quiet, and made of cheap materials that were commonly within reach."

Despite that origin, ultimately written request In light of the Tamil rebels, and the terrorist potential of the submersibles used by drug cartels, Washington has reported no evidence that the new methods of drug transportation developed by organized crime groups are being used by extremist actors of a different nature. However, the U.S. is keeping its guard up given the high rate of shipments arriving at their destination undetected.

[1] REICH, S., & Dombrowski, P (2017). The End of Grand Strategy. US Maritime Pperations in the 21st Century. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, NY. Pg. 143-145

July 1 presidential election does not open a serious discussion on the fight against drug trafficking

The 'iron fist' that Felipe Calderón (PAN) began in 2006, with the deployment of the Armed Forces in the fight against drugs, was extended in 2012 by Enrique Peña Nieto (PRI). In these twelve years the status has not improved, but rather increased violence. In this 2018 elections none of the main candidates presents a radical change from model; the populist Andrés Manuel López Obrador (Morena) proposes some striking measures, but continues to count on the work of the Army.

▲The Mexican president on Flag Day, February 2018 [Presidency of the Republic].

article / Valeria Nadal [English version].

Mexico faces a change of sexenio after closing 2017 as the most violent year in the country's history, with more than 25,000 homicides. How has this status been reached ? Can it begin to be resolved in the coming years?

There are several theories about the beginning of drug trafficking in Mexico, but the most widely accepted argues that Mexican drug trafficking was born when Franklin Delano Roosevelt, president of the United States between 1933 and 1945, promoted the cultivation of poppy in Mexican territory with the veiled intention of promoting the production of large quantities of morphine to relieve the pain of U.S. soldiers during World War II. However, drug trafficking was not a serious national problem until the 1980s; since then, cartels have multiplied, violence has increased and crime has spread throughout Mexico.

The new phase of Felipe Calderón

In the fight against drug trafficking in Mexico, the presidency of Felipe Calderón marked a new stage. candidate of the conservative National Action Party (PAN), Calderón was elected for the six-year term 2006-2012. His program included declaring war on the cartels, with a "mano dura" (iron fist) plan that translated into sending the Army to the Mexican streets. Although Calderón's speech was forceful and had a clear goal , to exterminate insecurity and violence caused by drug trafficking, the result was the opposite because his strategy was based exclusively on police and military action. This militarization of the streets was carried out through joint operations combining government forces: National Defense, Public Security, the Navy and the Attorney General's Office (PGR). However, and despite the large deployment and the 50% increase in the expense in security, the strategy did not work; homicides not only did not decrease, but increased: in 2007, Calderón's first full presidential year, 10,253 homicides were registered and in 2011, the last full year of his presidency, a record 22,409 homicides were registered.

According to agreement with the high school of Legal Research (IIJ) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), in that record year of 2011 almost a quarter of the total Mexican population over 18 years of age (24%) was assaulted in the street, suffered a robbery in public transport or was a victim of extortion, fraud, threats or injuries. The fees of violence was so high that it surpassed those of countries at war: in Iraq between 2003 and 2011 there was a average of 12 murders per day per 100,000 inhabitants, while in Mexico that average reached 18 murders per day. Finally, it is worth mentioning that the number of complaints about this indiscriminate wave of violence was quite high leave: only 12% of the victims of drug-related violence reported. This figure is probably related to the high rate of impunity (70%) that also marked Calderón's mandate.

Peña Nieto's new approach

After the failure of the PAN in the fight against drug trafficking, in 2012 Enrique Peña Nieto, candidate of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), was elected president. With this, this party, which had governed for uninterrupted decades, returned to power after two consecutive six-year periods of absence (presidencies of Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón, both from the PAN). Peña Nieto assumed the position promising a new approach , contrary to the "open war" proposed by his predecessor. He mainly focused his security policy on the division of the national territory into five regions to increase the efficiency and coordination of operations, on the reorganization of the Federal Police and on the strengthening of the legal framework . However, the new president maintained the Army's employment in the streets.

Peña Nieto's results in his fight against drug trafficking have been worse than those of his predecessor: during his term, intentional homicides have increased by 12,476 cases compared to the same period in Calderón's administration and 2017 closed with the regrettable news of being the most violent year in Mexico to date. With just months to go before the end of his six-year term, and in a last-ditch effort to right the wrongs that have marked it, Peña Nieto brought about the approval of the Internal Security Law, which was voted by Mexico's congress and enacted in December of last year. This law does not remove the military from the streets, but intends to legally guarantee that the Armed Forces have the capacity to act as police, something that previously only had the character of provisional. According to the law, the military participation in daily anti-narcotics operations is not to replace the Police, but to reinforce it in those areas where it is incapable of dealing with drug trafficking. The initiative was criticized by critics who, while recognizing the problem of the scarcity of police resources, warned of the risk of an unlimited military deployment over time. Thus, although Peña Nieto began his term in office trying to distance himself from Calderón's policies, he has concluded it by consolidating them.

|

source: Executive Secretariat, Government of Mexico |

What to expect from the 2018 candidates

Given the obvious ineffectiveness of the measures adopted by both presidents, the question in this election year is what anti-drug policy the next president will adopt, in a country where there is no re-election and therefore every six-year presidential term means a change of face. The three main candidates are, in the order of the polls: Andrés Manuel López Obrador, of the Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (Morena); Ricardo Anaya, of the PAN coalition with the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD), and José Antonio Meade, of the PRI. López Obrador came close to reaching the presidency in 2006 and 2012, both times as candidate of the PRD (he had previously been leader of the PRI); he then created his own party.

Meade, who represents a certain continuity with respect to Peña Nieto, although in the electoral campaign he has adopted a more anti-corruption tone, has pronounced himself in favor of the Internal Security Law: "It is an important law, it is a law that gives us framework, that gives us certainty, it is a law that allows the participation of the Armed Forces to be well regulated and regulated". Anaya has also positioned himself in favor of this law, since he considers that a withdrawal of the Army from the streets would be "leaving the citizens to their fate". However, he supports the need for the Police to recover its functions and strongly criticizes the lack of responsibility of the Government in subject of public security, alleging that Mexico has entered a "vicious circle that has become very comfortable for governors and mayors". In any case, neither Meade nor Anaya have specified what turn they could take that would be truly effective in reducing violence.

López Obrador, from a left-wing populist stance, is a major change with respect to previous policies, although it is not clear how effective his measures could be. Moreover, some of them, such as granting amnesty to the main drug cartel leaders, seem clearly counterproductive. In recent months, Morena's candidate has changed the focus of his speech, which was first centered on the eradication of corruption and then focused on security issues. Thus, he has said that if he wins the presidency he will assume full responsibility for the country's security by integrating the Army, the Navy and the Police into a single command, to which a newly created National Guard would be added. He has also announced that he would be the only one to assume the single command: "I am going to assume this responsibility directly". López Obrador pledges to end the war against drugs in the first three years of his mandate, assuring that, together with measures of force, his management will achieve economic growth that will translate into the creation of employment and the improvement of welfare, which will reduce violence.

In conclusion, the decade against drug trafficking that began almost twelve years ago has result been a failure that can be measured in numbers: since Calderon became president of Mexico in 2006 with the slogan "Things can change for the better", 28,000 people have disappeared and more than 150,000 have died as a result of the drug war. Despite small victories for Mexican authorities, such as the arrest of Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman during the Peña Nieto presidency, the reality in Mexico is one of intense criminal activity by drug cartels. From the electoral proposals of the presidential candidates, no rapid improvement can be expected in the next six years.