From the heart of Africa

New preventive strategies against AIDS

Jokin de Irala.

Doctor of Medicine and Doctor of Public Health.

Epidemiology and Public Health Unit.

University of Navarra.

Published in Diario de Navarra, December 2, 2003.

As World AIDS Day approaches, some may have been surprised by the discouraging data media reports on the terrible progress of AIDS in the world. So far in 2003, five million people have been infected and three million have died of the disease. The epidemic is particularly devastating for women; in some countries, 60% of women of reproductive age are infected. Of particular concern are some cases such as in Africa where life expectancy is as low as 37 years in Malawi. Here, life expectancy is 80-85 years.

I speak of "surprise" because this contrasts with the fabulous international campaign that has been carried out for so long in favor of the use of condoms as a priority preventive strategy against the advance of this disease that is annihilating entire generations of human beings. The campaign is carried out with unprecedented technical and economic means, with the massive support of the media and politicians of all persuasions. Certain situations are taken for granted, such as the opportunism of manufacturers who "generously" distribute thousands of condoms in schools or at youth parties.

In the face of this status, a minimum of critical sense should lead us to ask ourselves: How is it possible that an epidemic continues to wipe out entire populations despite such a deployment of supposedly preventive means; why do the authorities, at whatever level, not take into account certain scientific evidence on these issues?

Some international recommendations for AIDS prevention state, firstly, that abstinence is the only safe method to avoid infection; secondly, if abstinence is not possible, people should be advised to have mutually monogamous sexual relations with uninfected persons; and only thirdly, they warn people that condoms can reduce the risk of infection, but never eliminate it completely. The scientific data (database Cochrane, 2003) indicate that condoms reduce the risk of contagion by 80% (but promiscuity increases the real probability of contagion). In spite of this, it seems that those responsible for health at many levels are only interested in announcing that "condoms protect against infections".

On the other hand, I find it disappointing that they do not talk about other serious epidemics, such as the Human Papilloma Virus, which causes cancer and is increasing rapidly among young people. In this case, condoms are not very effective because the virus is not transmitted by seminal route but by contact skin-to-skin. In a scientific study published this year and carried out in a group of university women, it is shown that after 3 years, 40% of women ended up infected by this virus and in several of the students even without having had full sexual intercourse.

The latest data on the progress of AIDS in the world has recently been published and it turns out that, in some places, such as Uganda, the problem seems to be gradually coming under control. It would be interesting to hear more about what is happening in Uganda, as this could be a small glimmer of hope. The United Nations and the World Health Organization's report 2003 states that "no other country has matched this achievement, at least not at the national level", but without giving more details. In Uganda they have gone from having 15% infected in 1991 to 5% in 2001. The report states that this decrease is "unique in the world".

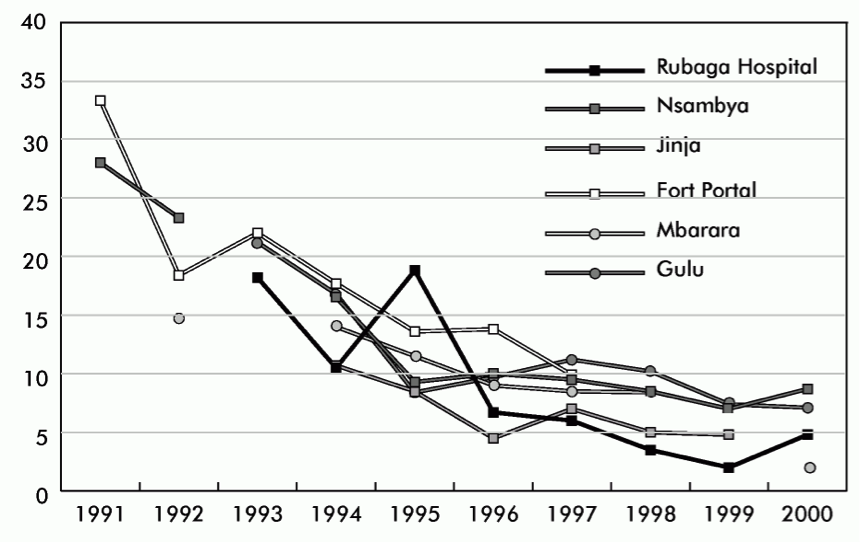

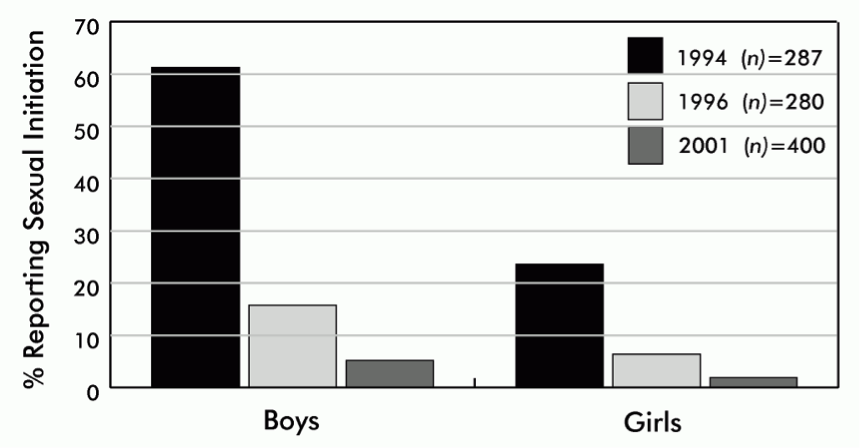

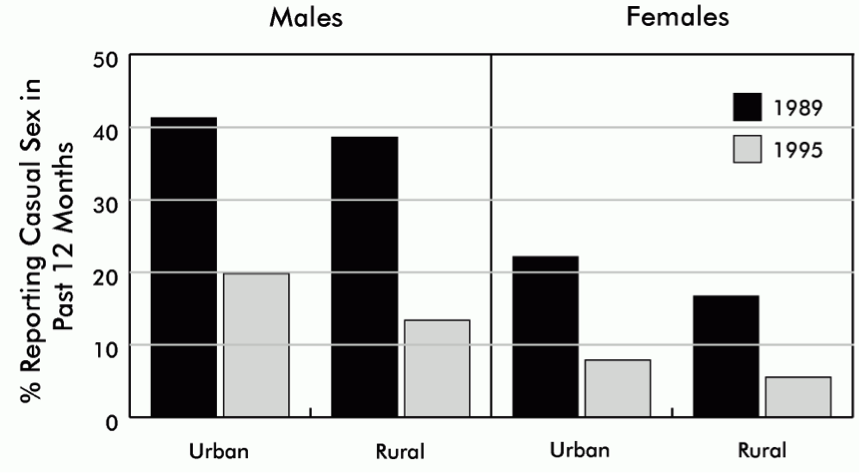

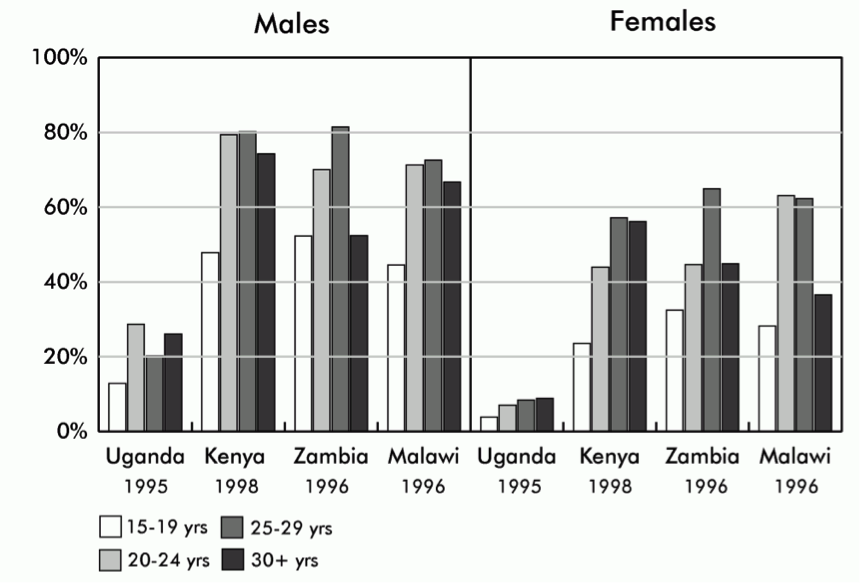

What really happened in this African country? There is a scientificreport from the United States Agency for International development (USAID, September 2002) entitled: "What has happened in Uganda; lessons learned from a project", which details the reasons for the paradoxical decline of AIDS in this country (see cover of the document). It turns out that in Uganda they have implemented preventive strategies based on the three international recommendations mentioned above and have managed to curb the epidemic (Figure 1). As can be seen in Figures 2, 3 and 4, they have succeeded in getting young people to delay the onset of sexual relations (recommending abstinence) and in getting the population to have less sporadic sexual relations, whether or not they coincide with a stable relationship. The report concludes, among other things, that Uganda's preventive strategy is achieving an effect that could be compared to "the existence of a vaccine that would be 80% effective against AIDS". On the other hand, they state that "the decrease in AIDS cases in Uganda is more related to changes in the population's lifestyles than to the use of condoms".

Figure 1. Proportion of HIV-infected pregnant women between 15 and 19 years of age.

The proportion of infected women is decreasing from about 35% in 1991 to less than 10% in 2000.

Delayed onset of sexual relations among students aged 13 to 16 years.

It is observed, for example, that the proportion of males between 13 and 16 years of age who initiate sexual relations at these ages declines from approximately 60% in 1994 to approximately 5% in 2001.

Proportion of the population reporting having had sporadic sexual relations outside of a stable relationship in the last 12 months.

At both the rural and urban levels, the proportion of people having sporadic sex declines from 1989 to 1995. For example, this proportion drops from approximately 40% in 1989 among men in large cities to 20% in 1995.

Frequency of sexual relations outside the usual partner in the last 12 months and in unmarried persons.

The figure sample shows that Uganda is the African country with the lowest proportion of sporadic sex outside the usual stable partner, across all age groups.

What is being done in many countries is simply irresponsible. Blindly relying on condoms without contributing anything else to the preventive strategy, when it has been seen that it has not even been enough to curb the epidemic in groups, a priori highly motivated, such as homosexuals, is a mistake that could end up paying dearly. This is indicated by some future projections of a possibly infected youth population. People could demand from their authorities more seriousness and originality in solving these serious problems. They should at least ask for the same courage that they have had to, for example, seriously initiate the important fight against smoking. We cannot remain impassive, naively believing that such a complex problem can be solved with a "patch" such as condoms.