▲Lower course of the Nile River, Egypt [Pixabay].

March 9, 2018

ANALYSIS / Albert Vidal [English version].

Disputes over the control of rivers, lakes and, final, water, are particularly intense today and will intensify in the near future, since, according to the World Health Organization, by 2025 half of the world's population will be living in areas with water shortages. Currently, the countries with the most water reserves are Brazil, Russia, USA, Canada, China, Colombia, Indonesia, Peru, India and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Most of the available water is underground, concentrated in aquifers, or is surface water (rivers and lakes). The aquifers with the largest reserves are the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System (under the Sahara Desert), the Great Artesian Basin (in Australia) and the Guarani Aquifer (in South America). On the other hand, there are a number of rivers in the world whose importance is exceptional, simply because of the huge amount of population and economic activity that depends on them. Problems arise when these rivers are not part of a single State, but are contiguous or transboundary rivers, and this leads to disputes between some States.

Tension hotspots in Asia

Asia is being particularly affected by this problem. There are currently several tensions revolving around the control of water. One of the most significant cases is the use of water from the Indus River, which supports 300 million people and has caused tensions between Pakistan and India. This river is a vital resource for both countries. With Pakistan's independence, the Indus became a source of dispute. This was addressed by the Indus Waters Treaty (1960), which gave India the three eastern tributaries (the Sutlesh, the Ravi and the Beas) and Pakistan the three western rivers (the Indus, the Jhelum and the Chenab). But due to water scarcity, Pakistan has recently protested against the construction of dams on the Indian side of the river (in Indian-administered Kashmir), which restrict water supply to Pakistan and reduce the river's flow. India, for its part, defends itself by saying that these projects are covered by the Treaty; even so, tensions do not seem to be easing. Pakistan has therefore asked the World Bank order appoint the president of an international arbitration tribunal to settle the dispute. This problem of water reserves is at the heart of the Kashmir dispute: without adequate supplies, Pakistan would soon become a desert.

|

Basins in Central Asia [Wikimedia Commons-Shannon I].

|

|

Indus River Basin [Wkiwand].

|

In Asia, there is also a dispute over the Mekong River, which flows through Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos and Thailand. This conflict revolves around the construction of dams by various countries, as well as the exploitation of the resources provided by the Mekong River. Eleven dams are planned to be built along the river, which would produce a large amount of electricity and would be beneficial for some countries, but could threaten the food security of millions of people. The countries concerned (Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos and Thailand) formed the Mekong River Commission (MRC) in 1995. This commission was formed to promote dialogue and encourage fair and equitable use of the river's waters. The MRC has mediated between countries several times; in 2010 over the construction of a dam by Laos and Thailand, and the same status was given in 2013. The talks have not result very effective, and there are fears for the lives of millions of people, who could be affected should the conflict escalate.

The ineffectiveness of this body could be summarized as follows: decisions on dam construction are made directly without being submitted to the MRC, and construction companies put so much pressure on governments that it is very difficult to carry out environmental impact assessments. Moreover, since it is not a binding treaty, members end up ignoring its guidelines and prefer to "cooperate" in a broad sense. In any case, the talks continue even though, at present, the MRC does not seem capable of taking on the weight of the negotiations. This gives the conflict an uncertain and dangerous future.

A third source of friction concerns the ex-Soviet region of Central Asia. During the Cold War, these regions shared resources as follows: the mountainous republics (Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan) had abundant water, which they supplied to the downstream republics (Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) to generate electricity and irrigate crops. In turn, the downstream republics supplied gas and coal to Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan during the winter. But with the collapse of the USSR all that changed and there began to be water shortages and power cuts, as these independent countries decided to stop sharing water and power. As the think-tank International Crisis Group proclaims, "the root of the problem lies in the disintegration of the source-sharing system imposed by the Soviet Union in the region until its collapse in 1991".

Thus, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have decided to build hydroelectric dams on the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers to produce their own power to cope with constant blackouts (potentially lethal in winter). This, of course, will limit access to water for millions of people living in the other three republics, which has led to small-scale conflicts. Threats have also abounded, such as that of Uzbek President Islom Karimov, who in 2012 said: "Water resources could become a future problem that could lead to an escalation of tensions not only in our region, but in the whole continent"; he added: "I will not name specific countries, but all this could deteriorate to the point where the result would not only be a confrontation, but wars. Despite the threats, the projects have continued on their way, and therefore an increase in tension in the region is to be expected.

|

The course of the Nile [Wikimedia Commons-Yale Environment 360].

|

|

Mekong River Basin [Wikimedia Commons-Shannon I].

|

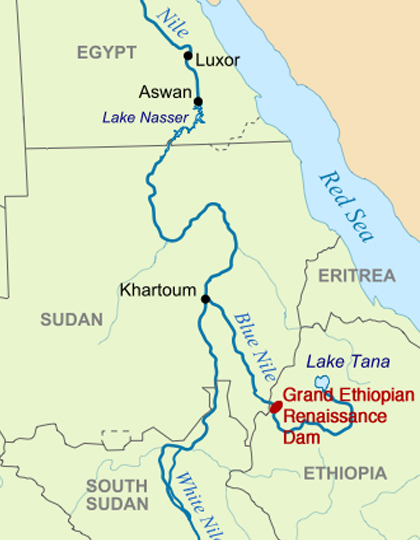

Control of the Nile

The Nile River appears as a source of tension between several African countries. To understand the existing problems, we must go back more than a century. As early as 1868, Egypt attempted to occupy Ethiopia in order to take control of the Nile River. In 1929, agreements were signed during the colonial era, in which the waters of the Nile were shared. In these agreements (which were reaffirmed in 1959), Egypt got most of the water for its use, while Sudan got a small share. The remaining 9 countries of the Nile Basin were removed from the treaty. At the same time, Egypt was allowed to build projects on the Nile River while the other riparian countries were prohibited from doing the same without Egypt's permission.

In 1999, the Nile Basin Initiative was created: a commission in charge of organizing a fair sharing of the water and resources of the Nile River. But not having the expected effect, the Entebbeagreement (by Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Burundi) was signed in 2010 as a consequence of the unequal sharing of water. This agreement, deeply disputed by Egypt and Sudan, allows riparian countries to build dams and other projects, thus breaking with the restrictions imposed by colonial treaties. Moreover, this has altered the balance in the region, as Egypt and Sudan have lost their monopoly over the Nile's resources.

It is vital to understand the geographical status of these actors. The Nile rises in several countries, and ends up passing through Sudan and Egypt to flow into the Mediterranean Sea. Egypt, in particular, is a country totally dependent on the Nile River. It receives more than 90% of its fresh water from this river, and its industry and agriculture need the Nile to survive. Until a few years ago, thanks to colonial treaties, Egypt had a monopoly on the use of the water, but recently the status has been changing.

Therefore, the confrontation has basically arisen between Egypt and Ethiopia (where the Blue Nile rises). The latter is a country with a population of over 100 million inhabitants, which in 2011 set up a dam construction project : the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam(GERD). With an investment of $4.7 billion, this dam would solve Ethiopia's energy deficit, and would turn the country into a net exporter of electricity (it would produce 6,000 MW per year). The drawback is that the dam will be fed by water from the Blue Nile, a tributary of the Nile River. The danger of evaporation of more than 3 billion cubic meters per year and the reduction of the flow to fill the reservation could have a catastrophic effect on Egypt. In addition to the dangers arising from the overuse of water, there is also population growth and the demand for a better redistribution of water among the riparian countries.

This issue has led to tensions between the two countries: in 2010 an email from a senior Egyptian commander was leaked on Wikileaks stating: "we are discussing military cooperation with Sudan against Ethiopia, with plans to establish a base in Sudan for Egyptian Special Forces to attack the GERD project ". Egypt also thought of preparing support for proxy rebel groups in Ethiopia, to destabilize the government. Anyway, we must keep in mind that Egypt has always tended to use an aggressive rhetoric towards any issue related to the Nilesource of life, engine of its Economics), but really the nation of the Pharaohs is not in a position to launch armed actions, since its domestic problems have worn the country down, thus losing its position of clear predominance in the region.

But not all the future is so black. In March 2015, a preliminary agreement was signed in Khartoum between Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan on the Renaissance Dam and water sharing, accepting Ethiopia's right to build the dam without damaging the water supply of Egypt and Sudan. Although these two countries are alarmed at what will happen once the reservation begins to fill, this is a first step towards an era of cooperation. Abdel Fattah el-Sisi (President of Egypt) himself said at the convention: "we have chosen to cooperate and trust each other, for the sake of development". Finally, in November of the same year, an independent analysis commission to observe the consequences of the dam could not be approve , because after Sudan accused Egypt of using part of the Sudanese quota, a war of declarations started, which endangered the fragile cooperation between these countries.

This cooperation in the field of water resources will have beneficial repercussions in many other areas and, although a failure of the negotiations cannot be ruled out, it is most likely that thanks to the construction of the GERD and regional cooperation, ties between these countries will become stronger, which may mark the starting point of a new era of peace and development in this region.

A case of cooperation: the Paraná

The Paraná, a border and transboundary river that originates in Brazil and crosses Paraguay to flow into the Río de la Plata, is a very different example. Its basin is linked to the Guarani Aquifer (one of the largest water reserves in the world), and that is a guarantee of the great water Issue that this river has throughout the year. For this reason, many hydroelectric power plants have been built, taking advantage of the waterfalls and rapids. On the other hand, the importance of this river at a political and economic level is a core topic; the Paraná and the La Plata Basin feed the most industrialized and populated area of South America. For this reason, cooperation has been especially important.

|

The Paraná, central axis of the La Plata basin [Wikimedia Commons-Kmusser].

|

The Itaipu dam (the second largest in the world and first in world production) is a bi-national dam, built by Paraguay and Brazil. It was the result of intense negotiations (not always easy), and now produces an average of 90 million MWh (megawatt-hours) per year. Even so, there was not always harmony between Paraguay and Brazil: in 1872, border disputes began. After many unworkable agreements, it was agreed to flood the disputed territories and create a hydroelectric dam. The reluctance that the initiative aroused in Argentina, because the regulation affected the flow downstream to the Rio de la Plata, resulted in a three-way agreement in 1979. In 1984 the dam came into operation. Today it is managed by the Itaipu Binational Entity, a public-private business between Paraguay and Brazil, and supplies more than 16% of the total energy consumed in Brazil, and more than 75% of that consumed in Paraguay. Although the environmental impact was great, Itaipu has promoted campaigns to maintain biological reserves and protect the fauna and flora. In addition, it has reforested large areas around the reservoir, and cares for the quality of the water.

This is a clear example of the benefits of reasonable and shared use between countries that decide to cooperate. Thus, countries that are party to some of the current controversies should look at these examples of behavior which, while not perfect, can learn a lot from them.

Although water can be the source of disputes between peoples and nations (as in the cases cited above), it also offers very advantageous opportunities (as in the case of the Parana or Nile rivers) for countries that manage to cooperate. This cooperation, initiated to avoid conflicts over water, can lead to new stages of harmony and strengthen commercial, political and security relations. It is core topic, then, to show how an attitude of willingness to negotiate and cooperate will always have positive consequences for countries sharing river flows.