Breadcrumb

Blogs

China, Russia and Iran have increased their relationship with needier Latin America due to Covid, which has also provided an opportunity for organised crime.

► Nicolás Maduro Guerra, after getting the Sputnik V vaccine, with the Russian ambassador in Caracas, in December 2020 [Russian Embassy].

report SRA 2021 / summary Executive [PDF version].

The severe health and economic crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has accentuated Latin America's vulnerabilities, also in terms of regional security. On the one hand, it has increased dependence on external powers, whose influence has grown through the delivery of vaccines (China and Russia) or petrol and food (Iran). On the other hand, it has taken away the means for states to combat organised crime, which has made some strategic moves, such as the consolidation of Paraguay as an important focus of drug trafficking. issue Although the status of prolonged confinement has made it possible to reduce homicides in some places, as in the case of Colombia, the deterioration of regional stability has led to greater US attention being paid to the rest of the Western Hemisphere, with a clear warning given by the US Southern Command.

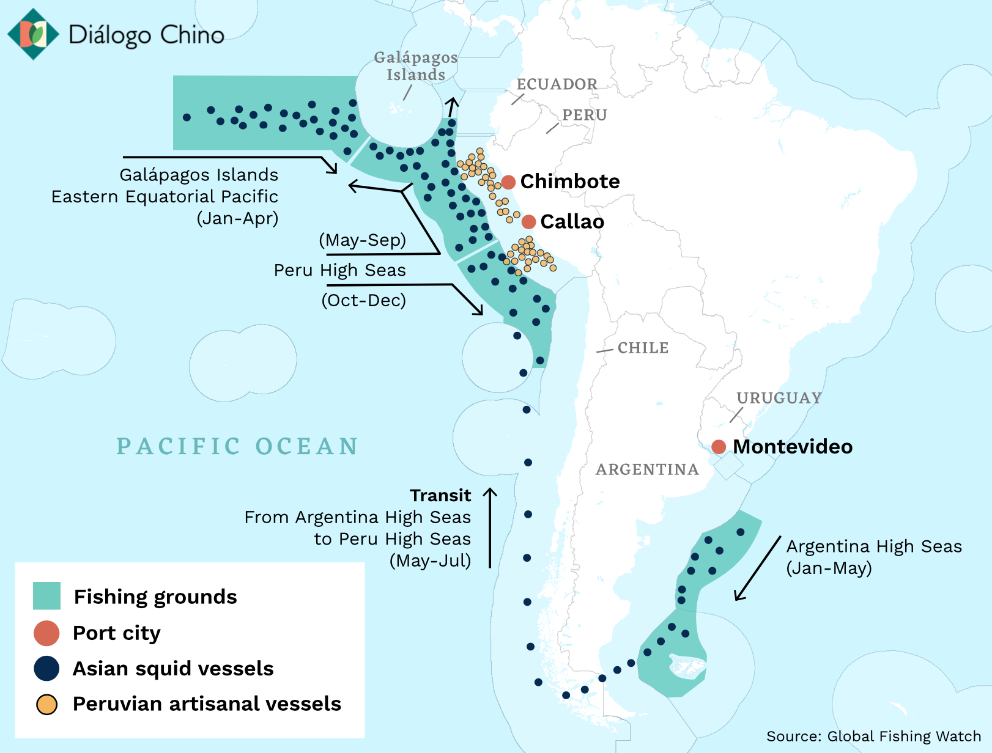

The needs imposed by Covid-19 across the globe have made some security requirements more pressing in certain countries. With international trade disrupted by movement limitations, China's food security concerns have pushed its long-distance fishing fleets to adopt more aggressive behaviour. Although a growing influx of Chinese fishermen has been detected in the waters around South America for some years now, in 2020, status marked a qualitative leap. The presence of more than 500 vessels raised concerns about the continuous evasion of radars, the use of unauthorised extraction systems and disobedience to coastguards. The governments of Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru issued a joint statement calling for oversight of an activity that Beijing refuses to submit to international inspection. The intimidation is reminiscent of the use of Chinese fishermen as a "strike force" in the South China Sea, although here the goal is not about gaining sovereignty but about fishing. Washington has expressed concern about China's activity both around the Galapagos and in the South Atlantic.

The pandemic has been a propitious occasion for China and, to a lesser extent, Russia to consolidate their penetration of Latin America. Thanks to "vaccine diplomacy", Beijing is now a fully global partner : not only commercial and a provider of loans for infrastructure, but also on a par with the United States and Europe in terms of pharmaceutical excellence and health provider . While it is true that Latin America is getting more "Western" vaccines - only Peru, Chile and Argentina have contracted more Chinese and Russian doses - the export of injectables from China and Russia has allowed it to increase its influence in the region. Huawei has managed to enter Brazil's 5G tender in exchange for vaccines, and Beijing has offered them to Paraguay if it abandons its recognition of Taiwan. In addition to clinical trials in several Latin American nations in the second half of 2020, Argentina and Mexico will produce or package Sputnik V from June.

The worsening humanitarian crisis in Venezuela throughout 2020, on the other hand, made it easier for Iran to strengthen its ties with Nicolás Maduro's regime, resuming a special relationship already in place during the Chávez and Ahmadinejad presidencies. With no more credits from China or Russia, Venezuela looked to the Iranians to try to reactivate the country's crippled refineries. Not particularly successful in that endeavour, Iran eventually became a supplier of more than 5 million barrels of gasoline via cargo ships; it also delivered food to supply a supermarket opened by the Iranians in Caracas. With oil production at a record low, Maduro paid for Tehran's services with shipments of gold, worth at least $500 million.

All this activity by extra-hemispheric powers in the region is identified by the US Southern Command, the US military structure responsible for Latin America and the Caribbean, as a cause of serious concern for Washington. In his annual appearances before the congress, the head of SouthCom has progressively raised the threat level to Degree . In his last appearance, in early 2021, Admiral Craig Faller was particularly alarming about China's advance in the region: he referred to the controversy over Chinese fishermen - their alleged encroachment on exclusive economic zones and illegal activity - and the $1 billion credit announced by Beijing for financial aid on Covid-19 health equipment. Faller said the US is "losing its positional advantage" and called for "immediate action to reverse this trend".

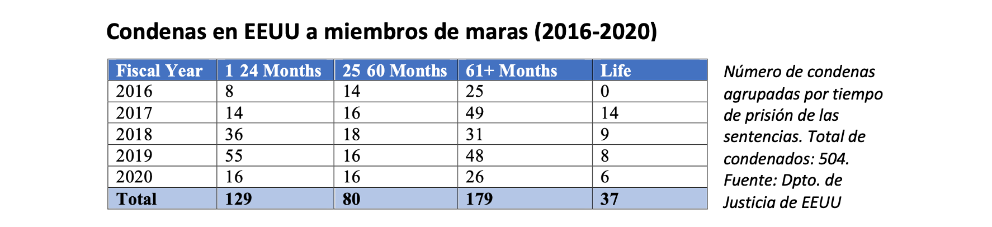

Another of Washington's concerns relates to transnational crime, specifically that perpetrated by Latino gangs in the US. In the last year, US federal prosecutors have for the first time charged members of the Mara Salvatrucha with national security crimes. The US continues to classify the gangs as a criminal organisation, not as group terrorists, but in charges filed in July 2020 and January 2021 against the MS-13 leadership imprisoned in El Salvador, some of its leaders have been upgraded to terrorists. The department of Justice considers the connection between the decisions taken in Salvadoran prisons and crimes committed in the US to be proven. In the last five years, US courts have convicted 504 gang members, 73 of whom received life sentences.

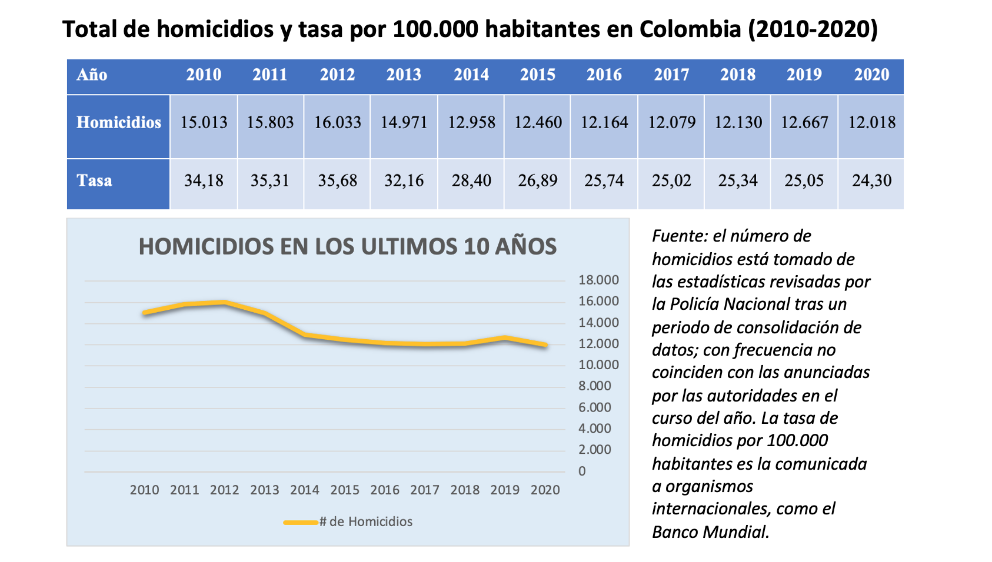

In terms of citizen security, the prolonged confinements for Covid-19 have allowed for a slight reduction in violence figures in some countries, especially in the first half of 2020. In the case of Colombia, this conjunctural effect was combined with the trend towards leave in the issue homicide rate that has been observed in the country since the beginning of the peace process negotiations in 2012, so that the 2020 figures represented a historic low, with a rate of 24.3 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, the highest leave since 1975. Several programs of study consider that there is a link between the demobilisation of the FARC and the consistent decrease in the level of violence that the country is experiencing. This is a positive development that is overshadowed by the murder of social leaders and ex-guerrillas, which at the beginning of 2021 had already risen to more than a thousand since the signature of the agreement de Paz in 2016.

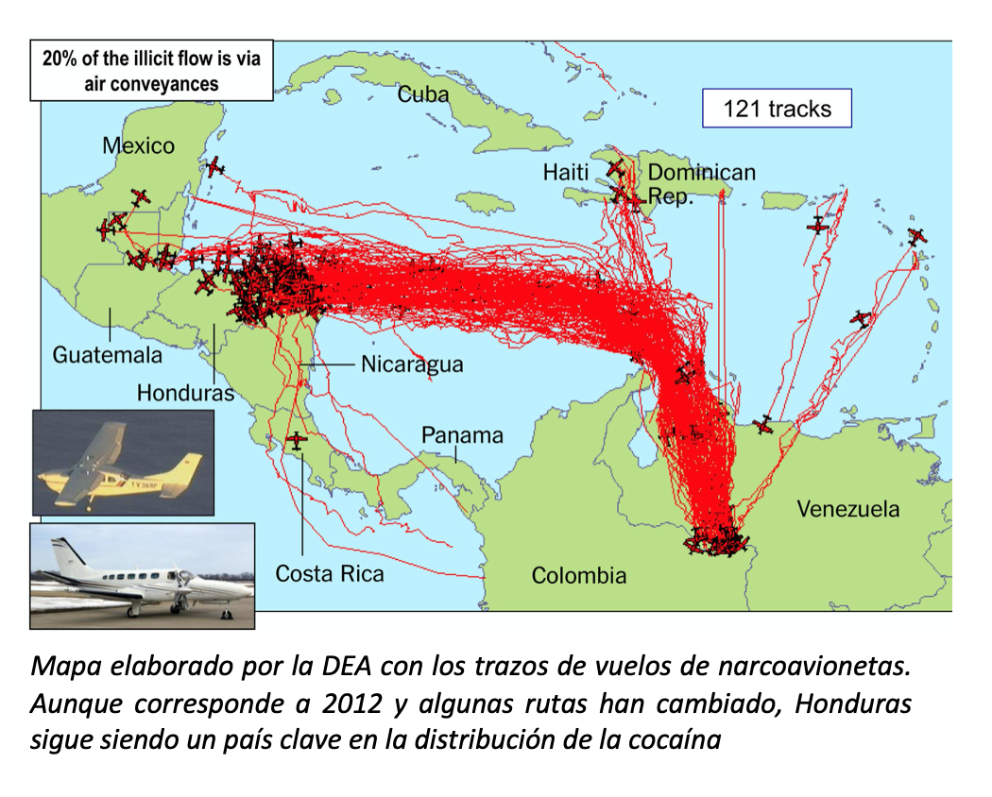

The drug trafficking chapter has seen two notable developments in the past year. One is the increase in "trial" coca cultivation in Honduras and Guatemala, which were previously only transit countries for cocaine. Both are consolidating their beginnings as producer countries, which is an important qualitative leap despite the fact that production is still very limited. After cocaine processing laboratories were located in both countries, the first plantations were discovered in 2017 in Honduras and in 2018 in Guatemala; since then, more than 100 hectares of coca bush have been detected, a very small number for the time being. Over the course of 2020, Honduras eradicated 40 hectares of cultivation and Guatemala 19. Part of this own-production infrastructure came to light in the US trial of Tony Hernández, brother of the Honduran president, who was sentenced to life imprisonment in March 2021.

For its part, Paraguay is on the rise on the drug trafficking map, as the largest producer of marijuana in South America and a distributor of cocaine from Peru and Bolivia. Most marijuana cultivation takes place around Pedro Juan Caballero, near the border with Brazil, which is the country's criminal centre. The plantations cover some 8,000 hectares, with production reaching 30,000 tonnes, 77% of which goes to Brazil and 20% to Argentina. At the beginning of 2021, more than 30 tonnes of cocaine shipped from Paraguay were located in northern European ports, making it a decisive distribution hub for the drug.

Most of the cultivation takes place in the area around Pedro Juan Caballero, near the Brazilian border, which is the country's criminal centre.

° Marijuana plantations cover some 8,000 hectares, with a production of 30,000 tonnes, 77% of which goes to Brazil and 20% to Argentina.

As a transit point for cocaine from Peru and Bolivia, Paraguay has seen a leap in the volume of shipments to Europe, with a record shipment of 23 tonnes at the beginning of 2021.

° The Paraguayan congress has C the medicinal use of marijuana; for the moment it is not following in the footsteps of Mexico, the leading producer in the Americas, which discussion its full legalisation.

Paraguayan President Mario Abdo Benítez and the then Argentinean Minister of Security, eradicating marijuana plants in PJC [Gov. of Paraguay].

report SRA 2021 / Eduardo Uranga [ PDF version].

Paraguay is on the rise on the drug trafficking map, as the largest producer of marijuana in South America and as a distributor of cocaine from Peru and Bolivia. With an estimated cannabis cultivation area of almost 8,000 hectares and an annual production of close to 30,000 tons, Paraguay exports the drug to Brazil and Argentina. finding The cocaine that passes through the country is destined for these two large neighbours and, above all, for Europe: in February 2021, the German authorities intercepted a 16-tonne cocaine shipment, the largest ever sent from Paraguay, an amount that rose to 23 tonnes in February 2021, including a shipment located two days earlier in Antwerp. A further 11 tonnes were found in Antwerp at the beginning of April.

While, in the case of Paraguay, the most surprising development in the last year has been this leap in the capacity to generate large cocaine shipments, the rapidly evolving international context in relation to marijuana - for example, the UN reclassified it in December 2020, noting its therapeutic potential - makes this other lucrative illicit trade particularly topical.

The growing legalisation of hemp leaf, which is beginning to take place in some countries, generating its own production (unlike coca, which due to its specific conditions is cultivated almost exclusively in Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, marijuana can be grown in different places, even in greenhouses) offers business prospects for the farmers who are currently involved in its illegal cultivation in Paraguay, This offers business prospects for the farmers who currently grow it illegally in Paraguay (not so much for the mafia structure of Brazilian origin, since in order to compete in Uruguay, the only nearby country that has legalised national production for open use, Paraguayan marijuana would have to be sold more cheaply than Uruguayan marijuana). Mexico, which is the largest producer in the Americas, is in the process of decriminalising recreational use; Paraguay is not there yet, but the law passed in August 2020 to allow medicinal use allows individual cultivation if there is medical certificate .

Production and eradication

Marijuana production is linked to organised crime, especially in the border areas with Brazil. According to figures provided by the administrative office National Anti-Drugs Office (SENAD), the largest operations against the cultivation of this drug take place in the department of Amambay, whose capital, Juan Pedro Caballero, is the country's criminal centre. This city is adjacent to the Brazilian border and shares an urban mass with the Brazilian town of Punta Porá. The adjacent department of Canindeyú, also bordering Brazil, is also home to extensive plantations.

In the decade 2009-2019, SENAD destroyed 9,838 hectares of marijuana plant cultivation in Amambay and 2,432 in Canindeyú, together accounting for about 90 per cent of the 15,045 hectares eradicated nationwide. In 2019, the latest damage referenced by SENAD, authorities eradicated 1,468.5 hectares, the highest figure of the decade, which not only indicates an increase in the anti-narcotics effort, but also suggests an increase in cultivated areas.

Paraguay is estimated to have between 6,000 and 8,000 hectares of marijuana plants. An improved seed introduced a few years ago has made it possible to expand the usual two harvests per year to three or even four harvests, raising productivity to between two and three tonnes of marijuana herb per hectare, bringing total production to as much as 20,000 tonnes per year. These figures may have been underestimated, as SENAD has estimated that up to 30,000 tons of weed could have left the country in the last year.

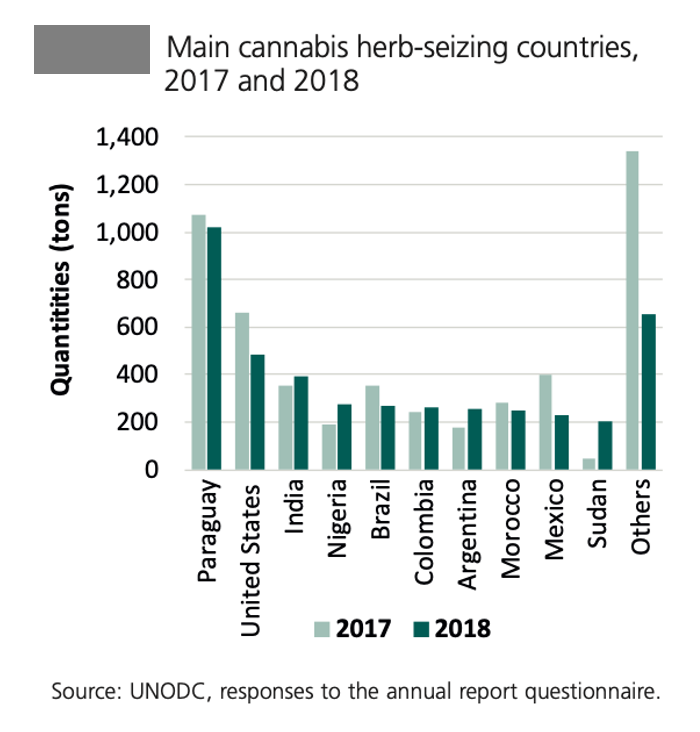

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) World Drug Report 2020 ranks Paraguay as the country with the largest marijuana seizures, at over 1,000 tonnes per year. The report also indicates that hemp resin production is minimal (1.1 tons in 2016) and that 77% of the marijuana generated in Paraguay is destined for the Brazilian market and 20% for the Argentinean market.

In the Americas, Paraguay's production is surpassed only by Mexico, which has an estimated 12,000 hectares of plantations, according to the US government's 2021 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR), agreement . The amount of cultivated area eradicated by the Mexican authorities is also higher, although this effort has fallen in recent years (5,478 hectares in 2016, 4,193 in 2017 and 2,263 in 2018), as indicated by the UNODC's report , which at the same time points out that in Mexico some 200 tonnes of marijuana were seized in 2018, compared to 400 tonnes in 2017.

Corruption

Paraguay is a fertile ground for the establishment of criminal networks. Its strategic position is a determining factor and a fundamental condition for it to be chosen by organised crime as a focal point for its criminal activities. Situated between the coca production centres of Peru and Bolivia and the growing markets of Argentina and above all Brazil, which are also a destination for Paraguayan marijuana, the country is a place of operation for mafias, especially Brazilian ones. The conditions of the Triple Border - the conurbation formed by Ciudad del Este (Paraguay), Foz de Iguaçú (Brazil) and Puerto Iguazú (Argentina) - also encourage smuggling, product counterfeiting and money laundering, as well as the financing of terrorist groups(such as Hezbollah).

Economic factors also play a role. Economic and social marginalisation is an element that these organised crime gangs resort to in order to recruit "employees". However, this factor can only partly explain the particular development of these networks. The scale of these networks depends fundamentally on the level of acceptance and tolerance of corruption. In this sense, Paraguay has the ideal conditions for the development of these networks. This is due to its high levels of state corruption, as indicated in the Corruption Perceptions Index.

Highlighting the obstacle that corruption in Paraguay poses to the fight against drug trafficking, in January 2020 a mass escape from a prison in Pedro Juan Caballero of 75 prisoners, mostly members of a Brazilian criminal gang First Capital Command (CCP), took place. The escape was facilitated by the collusion of officials and highlighted the impunity with which many of the drug traffickers operate.

Both are consolidating their beginnings as producer countries, which is an important qualitative leap despite the fact that production is still very limited.

° The first plantations were discovered in 2017 in Honduras and in 2018 in Guatemala; since then more than 100 hectares of coca bush have been located.

° During 2020, Honduras eradicated 40 hectares of coca cultivation and Guatemala 19 hectares; in addition, almost twenty cocaine processing laboratories were destroyed.

° The expansion of coca production into Central America is the work of Mexican cartels, which employ Colombian experts in locating the best areas for cultivation.

Honduran counter-narcotics action in a coca plantation in October 2020 [Gov. of Honduras].

report SRA 2021 / Eduardo Villa Corta [ PDF version].

Cocaine production has begun to spread to countries in Central America, which until recently were only transit points for cocaine coming mainly from Colombia, which is the world's largest producer, along with Peru and Bolivia.

The finding of drug processing laboratories in Honduras in 2009 already suggested the beginning of a shift, confirmed by the location of coca bush cultivation itself in 2017 in Honduras and in 2018 in Guatemala. Since then, more than 100 hectares have been located in both countries: some 50 hectares were counted together in those first two years, a figure that was doubled in 2020 in what appears to be an acceleration of the process.

In any case, these are very small areas, compared to those estimated by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime in its 2020 report for Colombia (around 180,000 hectares), Peru (almost 50,000) and Bolivia (around 25,000). Furthermore, the United States has so far claimed that it has no record of cocaine generated in the Central American Northern Triangle being found on its territory. entrance .

Everything indicates that for now we are in a stage of experimentation or essay by Mexican cartels, who are testing the aptitude terrain and climate of different areas and the quality of the product, with the help of Colombian experts, financial aid . Changes in the drug trafficking chain since most of the FARC left the illicit business in Colombia and the desire to reduce the complex logistics of transporting drugs to the United States explain these attempts in the Northern Triangle.

Honduras

In Honduras, the location of crops has increased in the last two years. The latest report of the International Narcotics Control Strategy (INCSR), from March 2021, prepared by the US State Department's department , includes official Honduran information that 40 hectares of coca bushes were eradicated in the first ten months of 2020. This represents an increase in the number of cultivation areas compared to previous years, which estimated the accumulation of 50 hectares throughout 2017 and 2018 in Honduras and Guatemala combined.

The first evidence in Honduras that drug trafficking was not only using its territory as a transit point was the finding in 2009 in the province of Cortés of a laboratory for the transformation of coca leaves into cocaine hydrochloride. In ten years, twelve laboratories were discovered and in 2020 alone the authorities proceeded to destroy at least another eleven, as indicated by the INCSR. Although some had the capacity to produce up to 3.6 tons of cocaine per year, their facilities were rather "rudimentary", according to Honduran law enforcement agencies.

The existence of these laboratories led to the conclusion that some amount of coca leaf may have been cultivated in the country since at least 2012, but it was not until 2017 that a cultivated area was found, in the province of Orlando, with some 10,000 plants. In 2018, three other farms were located, one of them 20 hectares in size. Cultivation activity and laboratory is not concentrated in a specific area, although half of the findings have been made in the aforementioned provinces of Orlando and Colón.

The last particularly noteworthy location, in an increasingly visible process of locating coca fields, was carried out by the National Directorate for the Fight against Drug Trafficking (DLCN) in March 2020, which corresponded to a field of some 4.2 hectares of cultivation and narco-laboratory in the Nueva Santa Bárbara community. In 2020, at least 15 coca fields were seized, with a total of 346,500 plants.

The DLCN believes that Mexican cartels, such as the Sinaloa and Jalisco cartels, are behind this penetration, although they do not operate directly, with a deployment of armed individuals, but on several occasions through growers of Colombian origin, who know how to take care of the coca plant.

Recent convictions in the US, such as that of the brother of Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández, have provided details of the drug trafficking corridor that is Honduras, but also the country's incipient homegrown production. As exposed in his trial, Tony Hernández, sentenced to life imprisonment in March 2021, had a direct relationship with a local cocaine laboratory .

Guatemala

In the case of Guatemala, the first finding of coca leaf cultivation took place in 2018. Although it was only one hectare in size, with 75,000 plants, it also marked the country's emergence as an incipient producer. In addition to having been, like Honduras, a transit channel for cocaine from Colombia, Guatemala had already distinguished itself for its moderate production of marijuana and for having begun to grow poppy, as an extension of the activity of Mexican cartels involved in the heroin market, of which Mexico is the leading producer in the Americas. Now Guatemala, where narco-laboratories have also appeared, included coca among its illicit narcotics crops.

In 2019, Guatemalan authorities made an effort to combat this activity. On 4 September of that year, they declared a 30-day state of siege in 22 municipalities in the north of the country. Police operations led to a number of seizures, especially in the Departments municipalities of Izabal, Alta Verapaz, Petén and Zacapa. Some 23 cultivation areas were located, eight of them in Izabal.

Following these findings, Interior Minister Enrique Degenhart admitted that Guatemala had become a cocaine-producing nation.

In the first ten months of 2020, 19 hectares of coca cultivation were eradicated and seven laboratories were destroyed, according to the latest INCSR, pointing out, in any case, that coca production in Guatemala is on a "limited scale" (as in Honduras, but even lower than in neighbouring Guatemala), at a distance from that of the largest South American producers.

Increased role for gangs

The Honduran and Guatemalan authorities fear, due to the increase in drug production activity, that some areas of their countries will become the new "Medellín of Pablo Escobar". The existence of areas that are difficult to access and the lack of resources for monitoring and combating organised crime complicate counter-narcotics efforts.

There is also a risk that the gangs or maras will gain even more power, entrenching or even aggravating the problem they pose. Because of their spatial dominance, they have so far collected tolls for the passage of drugs throughout the territory, but with production in the Northern Triangle itself, they could also come to control the very origin of the drugs, giving them the prerogatives of the cartels.

At the same time, international coordination against drug trafficking becomes more complicated, as it becomes more difficult to locate production sites and identify the actors involved.

The high issue of murdered social leaders continues to dismay the country: 904 assassinations since the 2016 Peace agreement

° In 2020 there were 24.3 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in Colombia, the most leave since 1975, when there was a similar rate, and below that of other countries in the region.

° The issue homicide rate in 2020 was 12,018, following the progressive decline recorded since 2002, only openly broken in 2012, when 16,033 murders were committed.

° programs of study concludes that there is a link between the demobilisation of the FARC and the consistent decrease in the level of violence that the country is experiencing.

Religious ceremony in Dabeiba in February 2020, after recovering the remains of a man who disappeared in 2002 [JEP]g

report SRA 2021 / Isabella Izquierdo [PDF version].

Colombia is gradually reducing its levels of violence, at least in terms of the homicide rate, which in 2020 fell to 24.3 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, the lowest figure leave since 1975. Although the drama of the murder of social leaders has overwhelmed Colombian society in the post-conflict management , the objectivity of the overall figures speaks of a reduction in violent deaths. This decrease has been driven in recent years by the FARC's withdrawal cessation of armed struggle and has presumably been favoured in 2020 by the prolonged confinements established to deal with the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The country closed 2020 with 12,018 homicides, the most leave in decades, less than half the number in the early 1990s, during the worst period of the armed conflict. At that time, issue homicides exceeded 28,000 per year, or around 80 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. Since then, with slight upturns in 2002 and 2012, Colombia has been reducing its levels of violence and today its homicide rate is far from the records being set by other countries in the region: although in some cases the health emergency has also helped to lower the figures, in 2020 the highest fees were those of Jamaica (46.5 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants), Venezuela (45.6), Honduras (37.6), Trinidad and Tobago (28.2) and Mexico (27).

(In the case of Colombia, the authorities spoke at the end of 2020 of a rate of 23.79, although later homicide figures from the National Police and data population figures give as result the estimate of 24.3 that has been chosen here).

Conflict and post-conflict

While ELN guerrillas remain active and several FARC dissidents continue to engage in criminal activities, around 8,000 ex-combatants were incorporated into civilian life as a result of the agreement peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC, which began negotiations in 2012 and was signed in 2016.

The years prior to the beginning of the contacts saw an increase in violence, and then a steady decrease since then, not only in violence related to the political conflict, but also in violence related to crime in general. When investigating the homicide fees during the years of the peace talks with the FARC, the Directorate of research Criminal and Interpol in Colombia revealed a close relationship: when the armed confrontation increased or decreased, depending on the interests of the negotiators, so did the total number of homicides. The good progress of the negotiation marked a dynamic of de-escalation of the armed conflict, with a reduction of 8.57% in the homicide rate between 2012 and 2015.

In 2017, after the signing of the peace agreement agreement , violence in Colombia reached its lowest levels in 30 years, with 12,079 homicides and a rate of 25.02 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. However, in 2018 the trend changed slightly (12,130 homicides), something that was pronounced in 2019 (12,667), which alerted to the need to rapidly implement the conditions for the reintegration of ex-combatants, improve security in demilitarised zones and increase state presence in the territory.

The high school of Medicina Legal concluded that the homicide figures for 2018 seemed to show a reactivation of the Colombian armed conflict. status For its part, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights presented in 2019 a report evaluating the human rights situation in Colombia, with emphasis on the implementation of the contents of agreement de Paz: the highest homicide figures were in Antioquia, Cauca and Norte de Santander, where the clashes for the control of illicit economies were most violent.

Effect of Covid

Post-conflict measures and the arrival of the pandemic, with its restrictions on movement, again led to a drop in homicides in 2020. In the period from 20 March to 17 August 2020, when the strictest confinements were in place, daily homicides per municipality fell, on average, by 16% from their pre-social distancing trend. In the weeks of full quarantine, the daily homicide issue even fell by around 40% from the pre-quarantine trend. From June 2020 onwards, the homicide issue returned to pre-emergency trends. Crime dropped in the first months due to fear of contagion, but quickly returned to the usual figures, especially in terms of robbery and theft, as the economic status worsened and the need for food among the poor increased. However, because of what happened in the first semester of the year, Colombia closed 2020 with thehighest homicide rate leave in the last 46 years.

A clear negative of 2020, however, was the continuation of violence directed against social leaders and ex-combatants. Last year, 297 local leaders were killed, bringing the total number of social actors killed from 2016 to February 2021 to 904. In the same period, 276 former guerrillas were killed, most of them involved in appearances before the Special Jurisdiction for Peace.

Federal prosecutors charge El Salvador's mara leadership with national security offences

° The US still classifies gangs as a criminal organisation, not as group terrorists, but in the last year it has come to consider some of their leaders as terrorists.

° The department of Justice considers the connection between the decisions taken by the MS-13 leadership from Salvadoran prisons and crimes committed in the USA to be proven.

° In the past five years, US courts have convicted 504 gang members, 73 of whom received life sentences.

Inmates of the maras in Salvadoran prisons, in April 2020 [Gov. of El Salvador].

report SRA 2021 / Xabier Ramos Garzón [ PDF version] [PDF version].

US authorities have in the past year taken a significant leap in their reaction to the violence of the main Latino street gang, the Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13. For the first time, federal prosecutors filed terrorism charges against the gang's leaders, opening the door to a review of the classification of MS-13, which has been considered an international criminal organisation in the US since 2012 and could be designated group terrorist, as is already the case in El Salvador.

The focus of the Justice department on violence with a Central American connection, however, may have been due to the Trump administration's prioritisation of the fight against illegal immigration. It is not yet known whether the Biden administration, which is less interested in criminalising immigration, will insist on the category of terrorism. However, police and judicial pressure on gang members responsible for crimes on US soil does not seem likely to diminish for the time being.

Tax offensive

In July 2020, the US Justice department released terrorism charges against Armando Eliú Melgar Díaz, alias Gangster Blue, sealed since the previous May in the Eastern District Court of Virginia. The charges included conspiracy to provide material support to terrorists, committing cross-border acts of terrorism, financing terrorist actions and conducting narco-terrorist operations. Melgar had lived in Virginia, with some absences, between 2003 and 2016, when he was deported. In November 2018, he was arrested and detained in El Salvador. Prosecutors believe he directed MS-13 criminal activity on the East Coast from El Salvador, apparently ordering and approving assassinations, overseeing drug trafficking businesses, and collecting money for local cliques or organisations.

Having opened this avenue of terrorism charges, which carry heavier penalties, against leaders who allegedly ordered the commission of crimes from El Salvador, the US Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of New York proceeded a few months later with the broadest and most far-reaching indictment against MS-13 and its command and control structure in the history of the United States, alleging crimes "against national security". Thus, in January 2021, the U.S. Attorney's Office made public an indictment, secretly formalised the previous month, with indictments against fourteen MS-13 leaders, all of them members of the Ranfla Nacional or gang leadership, which was headed, according to the Public Prosecutor's Office, by Borromeo Enrique Henríquez, aka Diablito de Hollywood. Eleven of them are in Salvadoran prisons and three are fugitives. The charges were similar to those brought against Melgar, but the indictment does not provide details of specific actions. The crimes of different cliques of the MS-19 are attributed to them, since, as part of its leadership, they were ultimately responsible for ordering the commission of many of the crimes. According to the prosecutor announcing the case, "MS-13 is manager of a wave of death and violence that has terrorised communities, leaving neighbourhoods awash in bloodshed". The US proceeded to prepare the respective extradition requests.

In addition to these two cases, which would fit into a conceptual framework that appears to seek to prosecute group terrorist leadership (even though terrorist status has not been applied by the United States to any gang, nor is there consensus on a narrow centralisation of criminal decision-making), several prosecutions of MS-13 members were launched in 2020 for crimes strictly related to murder, kidnapping, drug trafficking, weapons possession, and other organised crime activities. On the same day in July 2020 that the Melgar indictment was announced, the Eastern District Court of New York filed a case against eight members of the organisation and the District Court of Nevada against thirteen others; in August, the Eastern District of Virginia proceeded to arrest eleven more individuals associated with the gang.

These actions showed a commitment to enforce the investigations that had recently intensified, at the end of a presidential mandate that had made the fight against gangs one of the priorities of department Justice. Precisely at the end of 2020, this department published a report taking stock of the "efforts" carried out in this field between 2016 and 2020, graduate "Large-scale response". The report, which estimates that there are some 10,000 gang members in the United States, counts that 749 gang members were charged in US courts during this period; of these, 74% were in the country illegally, 8% were US citizens and 3% were legal residents. These prosecutions led to the conviction of at least 504 individuals, of whom 37 received life sentences.

The Attorney General also opened procedure to apply for the death penalty for two defendants involved in crimes that had a special social resonance. They are Alexi Sáenz, who is accused of seven murders, almost all of them using a machete or a baseball bat, and Elmer Zelaya, accused of coordinating the stabbing of two young men; most of the victims were teenagers. This extreme violence was highlighted by Donald Trump at several points during his term in office and he referred to it last July when the aforementioned terrorism cases were announced. He called the gang members "monsters who murder children", and indicated that the US authorities would not rest until "every member of MS-13" was brought to justice.

For its part, the FBI has formed Transnational Anti-Gang Units (TAGs) with security forces from several Central American countries, which since 2016 have been responsible for hundreds of arrests and have assisted in the extradition to the US of 68 defendants, 35 from Guatemala, 20 from Honduras and 13 from El Salvador.

Trajectory

Barack Obama's 2011 provisions empowering consideration of gangs as international criminal organisations, in the framework of a new National Strategy to Combat Transnational Organised Crime, were used by the Treasury'sdepartment in 2012 to apply that consideration to MS-13. The same categorisation was used in 2017 by the department Justice Department as the basis for the "war on gangs" launched by Trump. In 2018, the congress itself highlighted the dangerousness and incidence of gangs, in actions decided from El Salvador.

In 2019, Attorney General William Barr travelled to El Salvador, where he gathered information from the Salvadoran authorities, whose Supreme Court had already designated the maras as group terrorists in 2015. Alleged evidence of the chain of command, which connects orders for assassinations and other crimes given from Salvadoran prisons and their execution in the United States, reportedly underpinned the 2020 decision to open terrorism cases against gang members in US federal courts.

This change in the subject offence can be core topic in the future of the fight against gangs by offering a number of advantages, as there is no statute of limitations on terrorism charges and they have harsher penalties associated with them. International law also provides a greater arc and leeway for countries fighting terrorism, so cooperation between countries could be greatly enhanced; indeed, making charges comparable in the US and El Salvador could speed up extradition requests.

However, the move is not Exempt controversial. In the same way that international drug trafficking charges against the gang members have been of little use, since they do not properly constitute a transnational drug cartel, it remains to be seen how effective it would be to invoke terrorism charges in this case, given that the maras, at least in the US, do not have the range of features of a terrorist organisation: there is certainly not the element of wanting to be a political actor. In any case, as Steven Dudley, co-director of Insight Crime and author of MS-13: The Making of America's Most Notorious Gang, has said, the US government's decision to charge the visible leaders of MS-13 in El Salvador with terrorism "may be a sign of how poorly they understand this gang or how well they understand their judicial system".

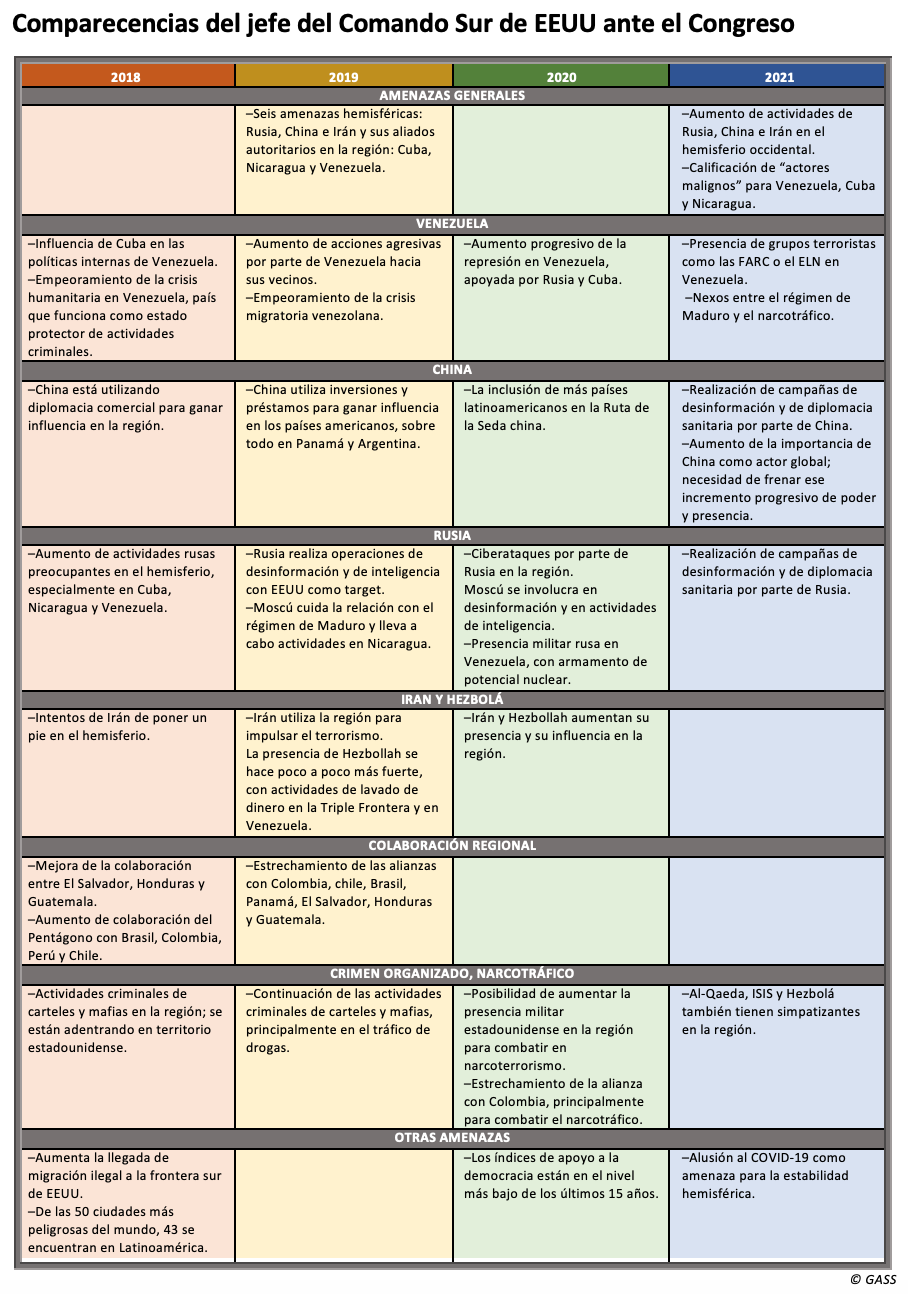

The USSOUTHCOM chief's appearance on Capitol Hill raises the annual Degree alert to Chinese influence and US pushback.

° In his latest appearance, Admiral Craig Faller warned that the US "is losing its positional advantage' and called for "immediate action to reverse this trend".

° In recent years the Southern Command's speech at congress has highlighted the penetration of China, Russia and Iran, hand in hand with Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua.

° Analysis of the Pentagon chief's interventions in the region sample the growing involvement of the Maduro regime in criminal activities.

► visit of the head of the US Southern Command to Montevideo in April 2021 [SouthCom].

report SRA 2021 / Diego Diamanti [ PDF version] [PDF version

The US Southern Command - the military structure within the US Armed Forces responsible for Latin America and the Caribbean - has been progressively raising the alarm about the growing influence of Russia and especially China in the Western Hemisphere, to the detriment of the US position. This, combined with the threat posed by organised crime organisations, especially those involved in drug trafficking, led USSOUTHCOM chief Admiral Craig Faller to confess in March to feeling "an incredible sense of urgency": "the hemisphere we live in is under attack", he said in his annual appearance before the US congress , dedicated to analysing the threats and opportunities the region presents in terms of security.

In his third "posture statement" to the congress since heading Southern Command, Faller warned that the US is losing its "edge" in the hemisphere and argued that "immediate action is needed to reverse the trend". Analysing his 2019 and 2020 speeches, as well as that of his predecessor, Admiral Kurt Tidd, in 2018, there is a worsening perception of the rivalry with China. Increasingly, the reference letter to the Chinese threat is more explicit and occupies more space. What was first seen as economic leverage, through increased trade and credit allocation, is now presented as more global and strategically more dangerous. According to Faller, China is seeking to 'establish a global logistics and infrastructure base in our hemisphere to project and sustain military power over greater distances'.

The change of Administration has not brought about any change in this worsening perception of the risks being generated in Latin America. Although Joe Biden's presidency has meant a change in tone from that of his predecessor, hostility towards Beijing and the desire to closely monitor other authoritarian regimes such as Russia and Venezuela have been maintained. Hence, the "posture statement" presented this year by the head of the Southern Command is consistent with previous ones in pointing to the growing activity of Russia and China in the region (and of Iran, in coordination with Hezbollah), as well as its partnership with Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua, countries that Faller called "malign regional state actors".

The use of Cuba

One of the constant and recurring threats that is gradually increasing is China's economic diplomacy strategy in several countries in the region: through loans and investments, Beijing incorporates these countries into its international trade network , sometimes integrating them into the New Silk Road initiative. The 2018 statement did not mention the issue number of Latin American nations participating in the initiative; the 2019 statement counted 16, and the 2020 statement spoke of 19, indicating a clear trend that China is gradually increasing its activities and influence in the hemisphere. The 2020 strategy also stated that 25 of the 31 countries in the region have Chinese infrastructure projects, which, as the head of the Southern Command expressly points out, could be used in the future to support Chinese military interests. Added to all this is the COVID-19 crisis, which China has used to increase its regional influence through its potential for medical supplies and vaccines.

Venezuela features prominently in the last four statements. Over the years, the situation progressively worsens and the Southern Command's stance towards Maduro's regime hardens: it goes from not calling him illegitimate to calling him illegitimate, and then openly accuses him of involvement in drug trafficking activities. It underlines its close military collaboration with Russia and with Colombian narco-terrorist groups - the ELN and FARC dissidents - which it hosts on its territory.

Another aspect that is reiterated is the emphasis on Cuba's destabilising role: how Havana interferes in internal affairs in Venezuela and Nicaragua, instructing these oppressive regimes on how to repress opposition movements and demonstrations, sometimes sending its own agents to fulfil this repressive function. In addition, the strategy also addresses the fact that Russia uses Cuba as a base for its intelligence operations towards the US and to project its power in the region.

The Southern Command's statements are in line with the concerns expressed in the document framework Strategic for the Western Hemisphere, produced by the National Security committee in 2020. Although the Trump Administration will have to formulate its own strategic plan for the region, no substantial changes can be expected, given that there is the same interest in restoring democracy for Nicaragua, Venezuela and Cuba; in promote transparency and fighting corruption; in combating illicit activities, such as drug trafficking and human smuggling; and in addressing China's growing presence in the region.

With oil production at a record low, the Maduro regime has turned to the precious metal to pay for Tehran's services.

° With no more credits from China or Russia, Caracas consolidated in 2020 the reborn relationship with the Iranians, who are in charge of trying to reactivate the country's crippled refineries.

° In the past year, Iranian-delivered cargo ships have brought more than 5 million barrels of gasoline to the Caribbean nation, as well as products for its Megasis supermarket.

° The involvement of entities related to the Revolutionary Guard, declared group terrorist by Washington, makes any gesture towards the Biden Administration difficult.

► The Venezuelan Vice President and the Iranian Vice Minister of Industry inaugurate the Megasis supermarket in Caracas in July 2020 [Gov. of Venezuela].

report SRA 2021 / María Victoria Andarcia [ PDF version].

Venezuela's relationship with extra-Hemispheric powers has been characterised in the last year and a half by the resumption of the close ties with Iran seen during the presidencies of Hugo Chávez and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. With the financing possibilities provided by China (it has not granted loans to Caracas since 2016) and Russia (its oil interest in Venezuela, through Rosneft, was particularly constrained in 2019 by the Trump administration's sanctions on PDVSA's business) exhausted, Nicolás Maduro's regime once again knocked on Iran's door.

And Tehran, once again encircled by US sanctions, as it was during the Ahmadinejad era, has once again seen the alliance with Venezuela as an opportunity to stand up to Washington, while at the same time reaping some economic benefits in times of great need: shipments of gold worth at least $500 million, according to Bloomberg, are said to have left Venezuela in 2020 as payment for services rendered by Iran. If the credits from China or Russia were in exchange for oil, now the Chavista regime also had to get its hands on gold, as the state-owned PDVSA's production was at an all-time low, at 362,000 barrels per day in the third quarter of the year (Chávez took over the company with a production of 3.2 million barrels per day).

The change of partners was symbolised in February 2020 with the arrival of Iranian technicians to start up the Armuy refinery, abandoned the previous month by Russian experts. Lack of investment had led to neglect of the maintenance of the country's refineries, which was causing severe petrol shortages and long queues at service stations. Iran's attendance would barely manage to improve the refinery status , and Tehran had to make up for this inefficiency by sending in gasoline tankers. Food shortages also provided another avenue of relief for Tehran, which also dispatched ships with foodstuffs.

Gasoline and food

The Venezuelan-Iranian relationship, which without being completely eliminated had been reduced during the presidency of Hassan Rohani, as the latter focused on the international negotiation of the nuclear agreement to be reached in 2015 (known as JCPOA), resumed throughout 2019. In April of that year, the controversial Iranian airline Mahan Air received permits to operate in Venezuela on the Tehran-Caracas route. Although the airline has not marketed the air route, it has chartered several flights to Venezuela despite the closure of territorial airspace ordered by Maduro due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Mahan Air's operations served to transport Iranian technicians who were to be employed in efforts to restart gasoline production at the Paraguaná complex refineries, as well as material necessary for these tasks.

According to researcher Joseph Humire, these and other arrangements were allegedly prepared by the Iranian embassy in Venezuela, which since December 2019 has been headed by Hojatollah Soltani, known for "mixing Iran's foreign policy with the activities" of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). He estimates that Mahan Air would have flown around 40 flights in the first half of 2020.

Similarly, Iran has been sending multiple fuel tan kers to Venezuela to address petrol shortages. The first shipment came in a flotilla of tankers that, in defiance of US sanctions, entered Venezuelan waters between 24 and 31 May, carrying a combined 1.5 million barrels of gasoline. In June, another vessel arrived with an estimated 300,000 barrels, and three others brought 820,000 barrels between 28 September and 4 October. Between December 2020 and January 2021 another flotilla would have carried 2.3 million barrels. To this total of at least 5 million barrels of gasoline should be added the arrival of 2.1 million barrels of condensate to be used as a diluent for Venezuelan extra-heavy oil.

In addition to fuel, Iran has also sent medical supplies and food to help combat the humanitarian emergency the country is suffering. Thus, it is important to highlight the opening of the Megasis supermarket, which is linked to the Revolutionary Guard, an Iranian military body that the Trump Administration included in the catalogue of terrorist groups. The store sells products from brands owned by the Iranian military, such as Delnoosh and Varamin, which are two of the subsidiaries of the Ekta company, allegedly created as a social security trust for Iranian military veterans. The Ekta supermarket chain is subordinate to the Iranian Ministry of Defence and the Armed Forces Logistics, an entity sanctioned by the United States for its role in the development ballistic missiles.

Gold and Saab

This activity is of concern to the US. An Atlantic Council report details how Iranian-backed networks prop up the Maduro regime. Venezuelan oil minister Tareck El Aissami has been identified as the core topic actor behind the illicit network . He allegedly agreed with Tehran to import Iranian fuel in exchange for Venezuelan gold. According to agreement according to the Bloomberg information cited above, the Venezuelan government had delivered to Iran, until April 2020, around nine tons of gold worth approximately 500 million dollars, in exchange for its attendance in the reactivation of the refineries. The gold was apparently transported on Mahan Air flights to Tehran.

The negotiations may have involved Colombian-born businessman Alex Saab, who already centralised much of the Chavista regime's food imports under the Clap programme and was getting involved in Iranian gasoline supplies. Saab was arrested in June 2020 in Cape Verde when his private plane was being refuelled on an apparent flight to Tehran. Requested to Interpol by the United States as Maduro's main front man, the extradition process remains open.

The entities involved in many of these exchanges are sanctioned by the US Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control for their connection to the IRGC. The IRGC's ability to operate in Venezuela is due to the reach of network to support Hezbollah, an organisation designated as a terrorist organisation by the United States and the European Union. Hezbollah has successfully infiltrated Venezuela's Lebanese expatriate communities, giving Iran a foothold to grow its influence in the region. These links make it difficult for Caracas to make any gesture that might be attempted to facilitate any de-escalation by the new Biden administration of Washington's sanctions.

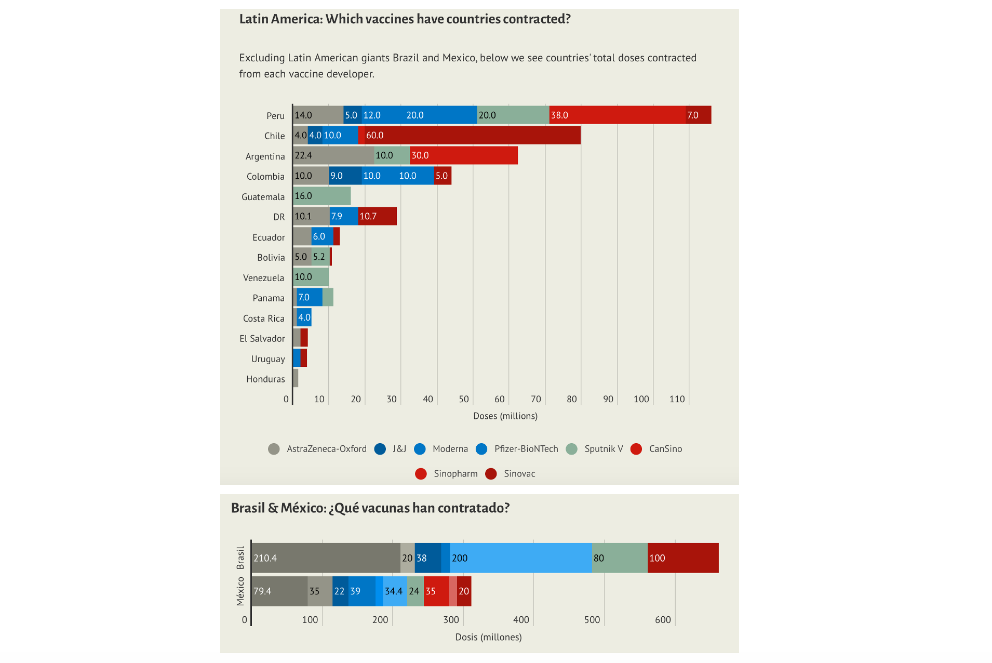

Beijing is no longer just a commercial partner and infrastructure lender: it is catching up with the West in pharmaceutical excellence and provider healthcare.

° Only Peru, Chile and Argentina have contracted more Chinese and Russian doses; in Brazil and Mexico, doses from the US and Europe predominate, as in the rest of the countries in the region.

° Huawei wins Brazilian 5G bid in exchange for vaccines; Beijing offers them to Paraguay if it abandons its recognition of Taiwan

° In addition to clinical trials in several nations in the second half of 2020, Argentina and Mexico will produce or package Sputnik V from June.

Arrival of a shipment of Sputnik V vaccines in Venezuela in February 2021 [Miraflores Palace].

report SRA 2021 / Emili J. Blasco [ PDF version].

Vaccination in Latin America is being done substantially with preparations developed in the United States and Europe, although media attention has privileged doses from China and Russia. The particular vaccine diplomacy carried out in recent months by Beijing and Moscow - which, with public funds, have promoted the export of injections ahead of the needs of their own inhabitants - has certainly been active and has managed to give the impression of greater influence than is real, often promising volumes of supplies that have rarely been delivered on time.

When, from June onwards, with most Americans already immunised, the Biden Administration turns its attention to providing vaccines to the region, the imbalance in favour of formulas from "Western" laboratories - also basically used in the UN's Covax system stockpiles - will be even greater. Nonetheless, the development of the health crisis over the past year will have served to consolidate China and Russia's foothold in Latin America.

To date, only Peru, Chile and Argentina have contracted more vaccines from China (CanSino, Sinopharm and Sinovac) and Russia (Sputnik V) than from the United States and Europe (AstraZeneca, J&J, Moderna and Pfizer). In the case of Peru, of the 116 million doses committed, 51 million correspond to European and/or US laboratories, 45 million to Chinese laboratories and 20 million to Russian laboratories. In the case of Chile, of the 79.8 million doses, 18 million are from the first group, while 61.8 million are Chinese. For Argentina, of the 62.4 million doses reserved, 22.4 million are "Western", 10 million are Russian and 30 million are Chinese. These are data from AS/COA, which keeps a detailed account of various aspects of the evolution of the health crisis in Latin America.

As for the two largest countries in the region, the preference for US and European formulations is notorious. Of the 661.4 million doses contracted by Brazil, 481.4 million come from the US, compared to 100 million Chinese doses and 80 million doses of Sputnik V (moreover, it is not clear that the latter will ever arrive, given the recent rejection of their authorisation by Brazilian regulators). Of the 310.8 million contracted by Mexico, 219.8 million are "Western" vaccines, 67 million are Chinese vaccines and 24 million are Sputnik V vaccines.

Tables: reproduction of AS/COA, database online, information as of 31 March 2021

Testing and production

The Chinese and Russian vaccines were not unknown in Latin American public opinion, as in the second half of 2020 they were frequently in the news as a result of clinical trials carried out in some countries. South America was of particular interest to the world's leading laboratories, as it was home to a high incidence of the epidemic along with a certain medical development that allowed for serious monitoring of the efficacy of the preparations, compatible with a level of economic need that facilitated thousands of volunteers for the trials. This made the region the focus of global clinical trials of the main anti-Covid-19 vaccines, with Brazil being the epicentre of degree program experimentation. In addition to trials conducted by Johnson & Johnson in six countries, and by Pfizer and Moderna in two, Sputnik V was tested in three (Brazil, Mexico and Venezuela) and in two by Sinovac (Brazil and Chile) and Sinopharm (Argentina and Peru).

Experimentation, however, was due to private agreements between laboratories, which required little involvement of the health or political authorities of the country in question. The commitment of certain governments to the Chinese and Russian vaccines came with purchase negotiations and then with their subsequent authorisation for use, a final step that has not always taken place. A further alliance in the case of Sputnik V has been Argentina's project to produce the Russian preparation on its territory from next June, for its own vaccination and distribution to neighbouring countries, as well as that of Mexico for the packaging of the doses, also from June. Argentina was the first country to register and approve Sputnik V, using information it has since shared with other countries in the region. Mexico's move has been interpreted as a way to put pressure on the US to liberalise the export of its vaccines as soon as possible.

China has also exerted pressure on some South American countries. It has taken advantage of Brazil's dire need for vaccines to force Jair Bolsonaro's government to allow Huawei to bid for Brazil's 5G network , despite having initially vetoed the Chinese business . Similarly, Beijing seems to have promised vaccines to Paraguay in exchange for the country ceasing to recognise Taiwan. In addition, the Chinese government last year averaged a billion-dollar credit for health procurement, as the head of the US Southern Command has warned, drawing attention to China's use of the crisis to gain further penetration in the hemisphere.

Consolidation

Whatever the final map of the application of each preparation in the vaccination process, what is certain is that above all Beijing, but in some ways also Moscow, has achieved an important victory, even though its vaccines may be far behind in the total number of doses injected in Latin America issue . In a region accustomed to identifying the United States and Europe with scientific capacity and high medical and pharmaceutical development , for the first time China is no longer seen as the source of cheap and unsophisticated products, but on a par in terms of research and health efficacy. Beyond Beijing's successful management of the pandemic, which can be relativised considering the authoritarian nature of its political system, China emerges as a leading country, capable of reaching a vaccine as quickly as the West and, to a certain extent, comparable to it. Russia's image lags somewhat behind, but Sputnik V consolidates Russia's "return" to a position of reference letter that it had lost completely in recent decades.

As a result of the emergence of Covid-19, in the collective Latin American imagination, China is no longer just a factor in trade, infrastructure construction and the granting of credits for development , but has established its penetration as a full-fledged power, also in terms of a central element in the lives of individuals, such as overcoming the pandemic.

Latin American countries have suffered the health and economic crisis of the coronavirus like no other region in the world. With 8.2% of the world's population, by October 2020 it accounted for 28% of global Covid-19 positive cases and 34% of deaths. The worsening of status in countries such as India may have changed these percentages somewhat, but the region has maintained important hotspots of infection, such as Brazil, followed by Mexico and Peru. To cope with this status, Latin America receives two-thirds of the IMF's global financial aid pandemic: the region has 17 million more poor people and will not recover its previous per capita income until 2025, later than the rest of the world.

China's growing fishing fleet sparks complaints of alleged encroachment into exclusive economic zones and illegal activity

° The presence of more than 500 vessels raises concerns about continued radar evasion, use of unauthorised extraction systems and disobedience to coastguards.

° The governments of Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru issued a statement calling for the supervision of an activity that Beijing refuses to submit to international inspection.

° Intimidation is reminiscent of the use of Chinese fishermen as a "strike force" in the South China Sea; here the goal is not about gaining sovereignty, but about fishing.

► The Chinese ship Hong Pu 16, followed by the Argentine patrol vessel ARA Bouchard, in May 2020 [Argentine Navy].

report SRA 2021 / Paola Rosenberg [ PDF version].

Over the last year, several Latin American countries have complained about Chinese economic predation, due to the massive presence of Chinese fishing boats in the vicinity of their Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and the poaching that is taking place there. They have also denounced the use by Chinese fishing vessels of unauthorised fishing techniques that deplete key fishing grounds and erode marine sustainability.

issue The arrival from China of fishing vessels of what is normally categorised as the Distant Water Fleet (DWF) began to occur in the Latin American maritime contour in 2001 with around twenty vessels; since then their number has been rapidly increasing and the most recent figures speak of some 500 ships. The unease of the most affected countries is not new, but in 2020 the complaints were louder and more formal. Moreover, in the open era of confrontation with Beijing, Washington came out in defence of the interests of its hemispheric neighbours.

China has the world's largest deep-sea fishing fleet, which is expanding as the fleets of other fishing nations are shrinking. Its size is unclear, as it often operates through small front companies that blur its national origin, but it has been estimated to total 17,000 vessels. In this activity far from China itself, the fleet catches two million tonnes of fish, accounting for 40 per cent of the world total in distant waters. Some of its catch is result illegal fishing; China has the worst record in the world for illegal fishing practices, according to Global Initiative's evaluation .

Map taken from China Dialogue and Global Fishing Watch

The strategic Galapagos

Fishing is one of the most important resources for several Latin American countries, which is why the massive Chinese presence in the vicinity of their exploitation waters, if there has been no penetration of these waters, has generated concern. In the last year, there have been many reports of Chinese fishing off Ecuador, Peru, Chile and Argentina, mostly linked to the capture of squid, but also of other species such as horse mackerel, mackerel, tuna and southern hake. These countries believe that overfishing and the capture of endangered species such as the giant squid are taking place, threatening the preservation of fish stocks and biodiversity, as well as the possession of false licences and the violation of the sovereignty of coastal states by allegedly illegally entering their EEZs. Fishermen from these coastal states increasingly report the presence of Chinese vessels in an intimidating attitude, carrying out acts that threaten not only their natural resources but also their security.

The main accusations came from July onwards in Ecuador. Earlier that month, the Ecuadorian navy warned of the presence of a Chinese fishing fleet of some 260 vessels fishing just outside the EEZ of the Galapagos Islands, which are under Ecuadorian sovereignty. By the end of the month, the fleet had increased to more than 342 vessels. The Galapagos archipelago was declared by Unesco as reservation of the biosphere, because it is home to hundreds of species of flora and fauna unique in the world. For this reason, exploitation in this area implies very large losses in terms of marine biodiversity.

In addition, half of the Chinese fleet behaved suspiciously, turning off the tracking and identification system. It was an evasion of marine radars that lasted for almost three weeks, as denounced by the Ecuadorian defence minister, Oswaldo Jarrín. The minister implied that this attitude was intended to conceal illegal fishing and perhaps also incursion into waters under Ecuadorian protection in order to fish there. In any case, he specified that the Ecuadorian navy was only able to find a couple of vessels within the Galapagos EEZ, which claimed to be using "innocent passage".

The country's president, Lenín Moreno, formally raised the complaints with the Beijing authorities, informing them that Ecuador would strongly assert its maritime rights over its EEZ, and announced a coordinated position with other Latin American governments. In fact, other countries in the region soon saw the Chinese fleet arrive in the vicinity of their waters. The ships left the corridor of international waters that exists between the Galapagos EEZ and the Ecuadorian coast, where they spent some time to catch the fish that migrate from one side to the other, and then moved south, first in the vicinity of the waters of Peru and Chile, and then, passing from the Pacific to the Atlantic, of Argentina.

These countries were backed by the United States, whose department of state said in August that the massive presence of Chinese fishing vessels and their internship to disable tracking systems, rename vessels and dispose of marine debris was "very troubling". President Donald Trump also spoke negatively on the occasion of his September speech to the United Nations. Washington has long been attentive to China's growing presence on the continent, not only commercially, but also in the management of strategic infrastructure such as port terminals. The Galapagos, specifically, have a special strategic value due to their status access routes to the Panama Canal.

Request for inspections

After Ecuador, due to the threat off their waters, Peru and Chile activated Global Fisheries Surveillance and mobilised air and naval patrols to closely monitor the advance of the Chinese fishing fleet. When the Chinese fishing fleet moved into the Atlantic in December 2020, the Argentine naval force also deployed naval and air units to ensure control over its maritime spaces.

In November, the governments of Ecuador, Chile, Peru and Colombia (the latter's EEZ borders the corridor between the two Ecuadorian maritime areas) issued a joint statement, in which they expressed their concern over the presence "of a large fleet of foreign-flagged vessels that have been carrying out fishing activities in recent months in international waters close to our jurisdictional waters". The grade chose not to explicitly mention China (moreover, several vessels in the fleet were flagged differently, although they were Chinese for all intents and purposes), but it was clear in which direction they were directing their denunciation of "fishing activities not subject to control or reporting".

Latin American countries are demanding that China agree to inspections, in the presence of staff if necessary, of suspicious vessels, even if they have remained in international waters. Beijing responds that it has already established moratoriums at certain times of the year on squid fishing in the region. However, the lack of cooperation so far and the growing demand from the Chinese market suggests that this subject of activities will continue to increase.

As it has done in the Pacific, the United States has sent Coast Guard vessels to the South Atlantic to confront Chinese incursions, in this case in joint exercises with Brazil and Uruguay. It is precisely with the latter country that Washington is trying to arrange some kind of subject of partnership that would allow for greater inspection of the maritime area , as it considers that Argentina could lend itself excessively to Chinese requirements.

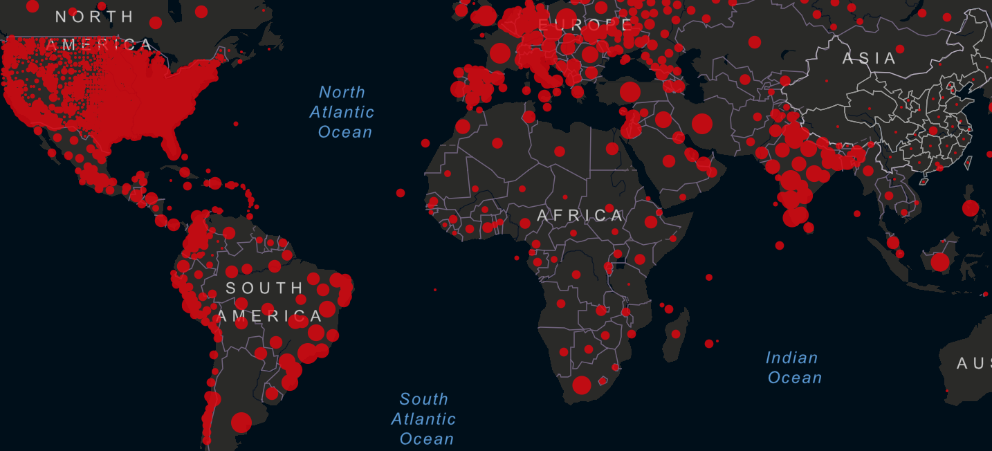

Image of the world map produced by the John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

report SRA 2021 / presentation

The pandemic caused by the Covid-19 virus has had a major impact on the entire world and especially on American nations: three of the four countries with the most deaths - the United States, Brazil and Mexico, with more than one million deaths - are in the Western Hemisphere. Latin America has been the area most affected by the disease, in proportion to its population, and with the worst economic consequences. This status has meant, in terms of security, a special regional vulnerability to external powers and internal mafias.

If two years ago we launched this report of American Regional Security (ARS) stating that geopolitics had returned to the continent, due to the growing interest of China and Russia in the area of traditional US influence, it can now be said that these two extra-hemispheric powers have taken advantage of the health emergency to deploy a "diplomacy of vaccines" and consolidate their influence, while the US prepares its own flow of neighbouring financial aid , on the verge of concluding the inoculation of its population.

In this context, significant episodes occurred during 2020. China's food security demands have reinforced the presence of Chinese fishing fleets in the vicinity of the waters of several South American countries, whose fishing grounds are threatened by illegal fishing practices and alleged encroachment on their exclusive economic zones. This has led to some collective security movement and increased engagement with the US Southern Command.

On the other hand, organised crime has also taken advantage of the pandemic status , relying on the distraction of the authorities in another subject of efforts. In the last year, Paraguay has emerged as a major hub for cocaine outflows from the interior of the continent, while at the same time consolidating its position as South America's main producer of marijuana, at a time when this crop is emerging as a legal business opportunity in new countries. For their part, Guatemala and Honduras are consolidating their 'trials' in coca cultivation, making a leap - scarcely quantitative, but certainly qualitative - in the world of drug trafficking. The positive news is that the peace process and the confinements of the pandemic have reduced homicides in Colombia to historic lows.

CONTENTS

summary executive

Covid makes Latin America more vulnerable to external powers and internal mafias

Maritime safety

China's uncontrolled fishing alerts governments with major fishing grounds under threat

Extra-hemispheric presence

Vaccine diplomacy: more 'Western' doses, but China and Russia consolidate penetration

Extra-hemispheric presence

Iran takes gold from a Venezuela that no longer has oil to pay for the favours.

US reaction

The US Southern Command is warning more about China's advance in the region.

Maras

US begins to prosecute MS-13 members as terrorists

Citizen security

Peace process and Covid reduce homicides in Colombia to historic lows

Drug trafficking

Coca cultivation 'trials' increase in Honduras and Guatemala, once only transit countries

Drug trafficking