U.S. Southern Command highlights Iranian interest in consolidating Hezbollah's intelligence and funding networks in the region

-

Throughout 2019 Rosneft tightened its control over PDVSA, marketing 80% of production, but U.S. sanctions forced its departure from the country

-

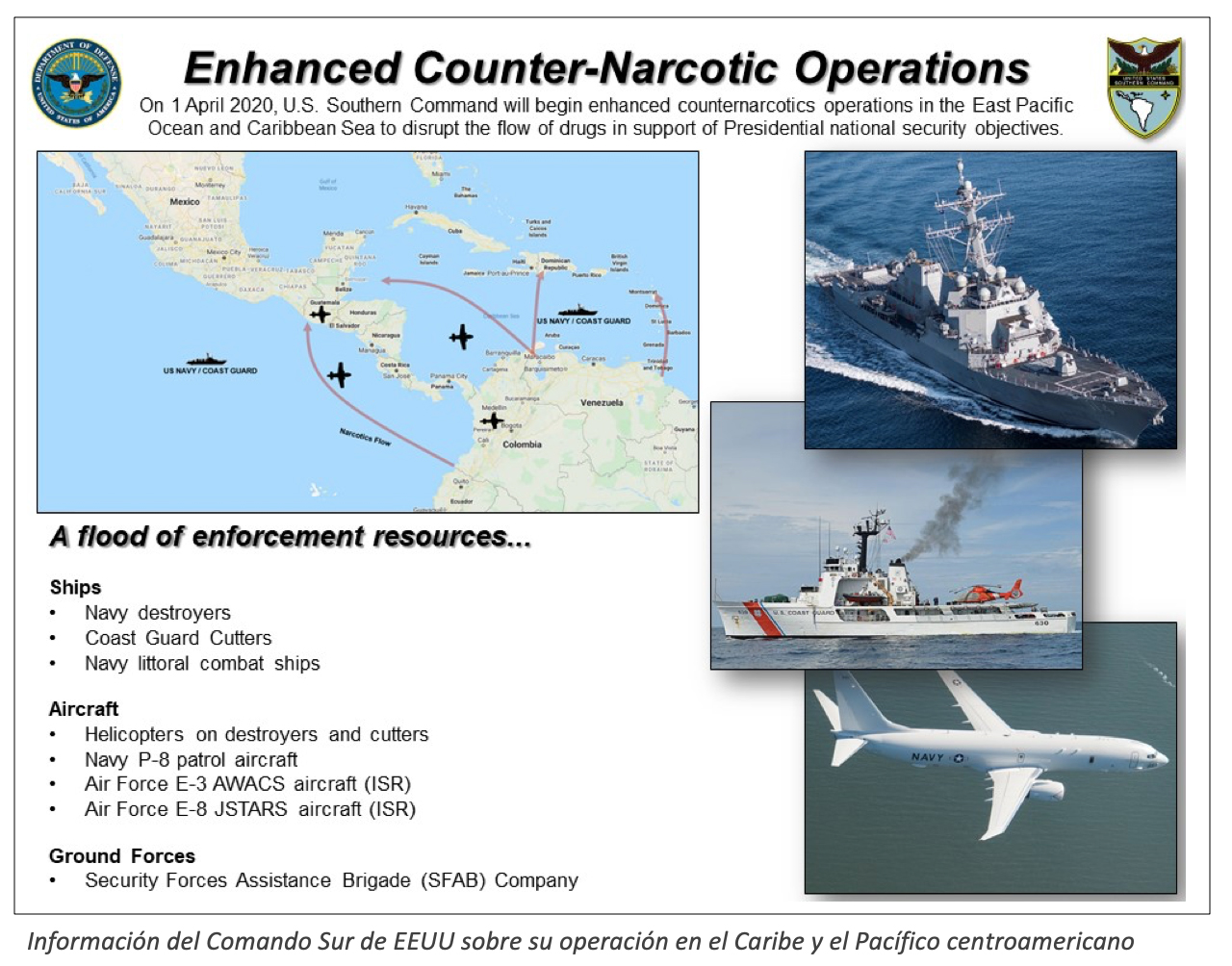

The arrival of Iranian Revolutionary Guard troops comes amidst a U.S. naval and air deployment in the Caribbean, not far from Venezuelan waters.

-

The Iranians, once again beset by Washington's sanctions, return to the country that helped them to circumvent the international siege during the era of the Chávez-Ahmadinejab alliance.

![Nicolas Maduro and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at a meeting in Tehran in 2015 [Hossein Zohrevand, Tasnim News Agency]. Nicolas Maduro and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at a meeting in Tehran in 2015 [Hossein Zohrevand, Tasnim News Agency].](/documents/10174/16849987/sra-2020-venezuela-iran-blog.jpg)

▲ Nicolas Maduro and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at a meeting in Tehran in 2015 [Hossein Zohrevand, Tasnim News Agency].

report SRA 2020 / Emili J. Blasco [PDF version].

MAY 2020-In a short period of time Venezuela has gone from depending on credits from China, to relying on the Russian energy sector (as was particularly evident in 2019) and then to asking for financial aid from Iran's oil technicians (as was seen at the beginning of 2020). If the Chinese public loans were supposed to keep the country running, the Rosneft aid was only intended to save the national oil company, PDVSA, while the financial aid from the Iranian Revolutionary Guard only aims at reactivating some refineries. Each time those who assist Venezuela are smaller in size and the purpose is more and more reduced.

In just ten years the large Chinese public banks granted $62.2 billion in credits to the Venezuelan government. The last of the 17 credits came in 2016; since then Beijing has disregarded the knocks Nicolás Maduro has given at its door. Although already since 2006 Chavismo had also received credits from Moscow, (some $17 billion, for the purchase of arms from Russia itself), Maduro turned to pleading with Vladimir Putin when the Chinese financial aid ended. Not wanting to give any more credits, the Kremlin articulated another way to help the regime that at the same time ensured the immediate collection of benefits. Thus began Rosneft's direct involvement in various aspects of the Venezuelan oil business, beyond the specific exploitation of some fields.

This mechanism was particularly relevant in 2019, when the progressive US sanctions on Venezuela's oil activity began to have a great effect. To circumvent the sanctions on PDVSA, Rosneft became a marketer of Venezuelan oil, controlling the placing on the market of most of the total production (between 60% and 80%).

Washington's threat to punish Rosneft also caused the company to shift its business to two subsidiaries, Rosneft Trading and TNK Trading International, which in turn gave up this activity when the United States pointed them out. Despite the fact that Rosneft generally serves the geopolitical interests of the Kremlin, the fact that its shareholding includes BP or Qatari funds means that the company does not risk its profit and loss account so easily.

The departure of Rosneft, which also saw no economic sense in continuing to get involved in reactivating the Venezuelan refineries, whose paralysis has plunged the country into a generalized lack of fuel supply to the population, left Maduro without many options. The Russians abandoned the Armuy refinery at the end of January 2020 and the following month the Iranians were already resuming the attempt to put it into operation. Within weeks Iran's new involvement in Venezuela became public: Tarek el Assami, the Chavista leader with the strongest connections to Hezbollah and the Shiite world, was appointed Oil Minister in April, and in May five cargo ships brought fuel oil and presumably refining machinery from Iran to Venezuela.

The supply did not solve much (the gasoline would barely be enough for a few weeks' consumption) and the Iranian technicians, at least some of them led by the Revolutionary Guard, were hardly going to be able to fix the refining problem. Meanwhile, Tehran was getting in return important shipments of gold as payment for its services (nine tons, according to the Trump Administration). The Iranian airline Mahan, used by the Revolutionary Guards in their operations, was involved in the transports.

Thus, suffocated by the new sanctions outline imposed by Donald Trump, Iran returned to Venezuela in search of economic oxygen and also political partnership with Washington, as when Mahmud Ahmadinejad allied with Hugo Chávez to alleviate the restrictions of the first sanctions regime suffered by the Islamic nation.

U.S. naval and air deployment

Iran's "interference" in the Western Hemisphere had already been mentioned, among the list of risks to regional security, in the appearance of the head of the U.S. Southern Command, Admiral Craig Faller, on Capitol Hill in Washington (in January he went to the Senate and in March to the House of Representatives, with the same written speech ). Faller referred mainly to Iran's use of Hezbollah, whose presence in the continent has been aided by Chavism for years. According to the admiral, that activity linked to Hezbollah "allows Iran to gather intelligence and carry out contingency plans for possible retaliatory attacks against the United States and/or Western interests."

However, the novelty of Faller's intervention was in two other matters. On the one hand, for the first time, the head of the Southern Command placed China's risk ahead of Russia's, in a context of growing rivalry between Washington and Beijing, which is also manifested in the taking of positions on Chinese investments in strategic infrastructure works in the region.

On the other hand, he announced a forthcoming "increased U.S. military presence in the hemisphere", something that began to take place at the end of March 2020 when U.S. ships and planes were deployed in the Caribbean and the Pacific to reinforce the fight against drug trafficking. In the context of his speech, this increased military activity in the region was understood as a necessary notice to extra-hemispheric countries.

"Above all, in this fight what matters is persistent presence," he said, "we have to be present on the field to compete, and we have to compete to win." Specifically, he proposed more joint actions and maneuvers with other countries in the region and the "recurring rotation of small special operations forces teams, soldiers, sailors, pilots, Marines, Coast Guardsmen and National Guard staff to help us strengthen those partnerships."

But the arrival of U.S. ships near Venezuelan waters, just a few days after the announcement on March 26 from New York and Miami of the opening of a macro-court case for drug trafficking and other crimes against the main Chavista leaders, among them Nicolás Maduro and Diosdado Cabello, gave this military deployment a connotation of physical encirclement of the Chavista regime.

That deployment also gave some context to two other developments that occurred shortly thereafter, offering misleading readings: the failed Operation Gideon on May 3, by a group of mercenaries who claimed to have the intention of infiltrating the country for Maduro (the increased transmission capabilities acquired by the US in the area, thanks to its maneuvers, were not used in principle in that operation), and the arrival of the Iranian ships at the end of the month (the US deployment raised suspicions that Washington could intercept the advance of the ships, which did not happen).