In the picture

View of the port of Arica, in the north of Chile, on the border with Peru [Port Authority].

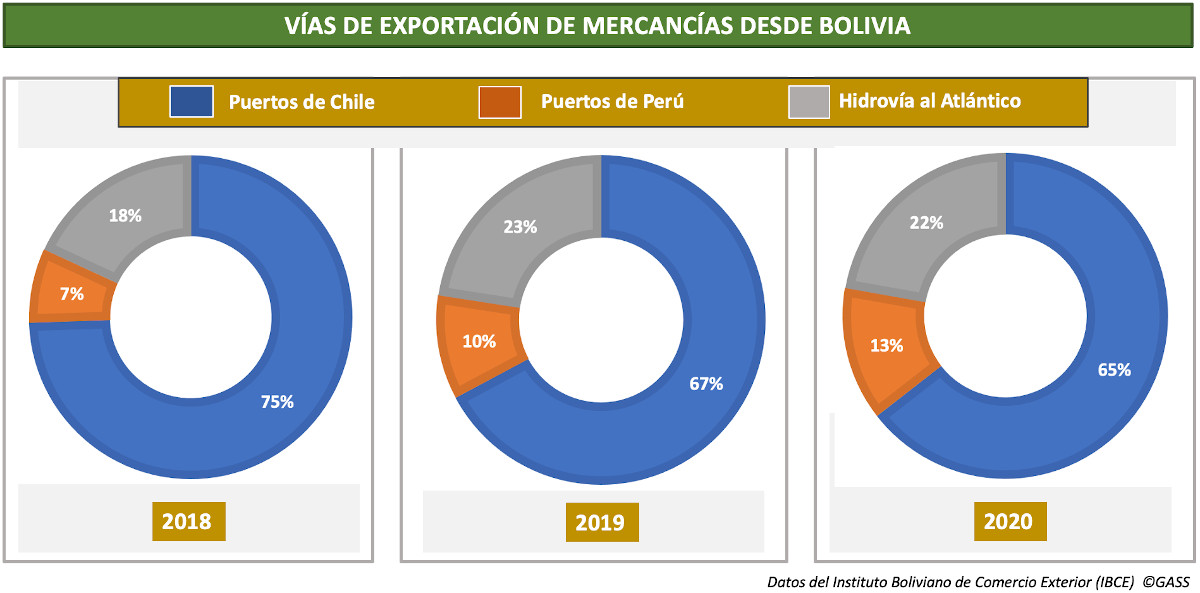

The ports of northern Chile have been the usual gateway for entrance and departure of maritime goods with origin or destination in Bolivia, putting into practice the port and transit facilities provided for in the treaty that ratified the borders between the two countries more than a century ago. However, Bolivia is developing logistical alternatives that provide less dependence on Chilean ports. Thus, the Issue of Bolivian cargo shipped in Chile has been reduced in recent years, from 74.4% of exported tons in 2018 to 64.4% in 2020. The increase in traffic through ports in southern Peru and the increased use of the Paraguay-Parana waterway, although totaling little Issue, expand the Bolivian room for maneuver.

The latest period of political friction between Bolivia and Chile, following the Bolivian attempt to have the International Court of Justice in The Hague force its neighbors to sit down at a negotiating table to talk about their mutual borders, has had its consequences in the area of trade. In October 2018 the Court ruled that Bolivia's loss of access to the sea as a result of the War of the Pacific (1879-1884) is a matter Closed and Chile cannot be forced into any cession. The diplomatic tension led the Bolivian government to an interest in promoting greater trade through Peruvian ports, something that was also assisted by an increase in tariffs in the Chilean port of Arica, which is the main traffic port for goods linked to Bolivia.

Although Chilean-Bolivian relations have returned to normal, the existence in Peru of a politically and sociologically like-minded government - the indigenism of the Andes unites Pedro Castillo and Luis Arce - has accentuated Bolivia's desire to further explore alternative routes, especially to the Peruvian port of Ilo. In addition, there is a public-private partnership between the government and the private sector to develop the docks that give access to the Paraguay-Paraná waterway, which reaches the Atlantic via the Río de la Plata.

In 2018, Bolivia exported a total of 5,140,467 tons of goods (hydrocarbons transported by pipeline are excluded). Of that Issue, the flow of Bolivian cargo through ports in Chile -first Arica and then Antofagasta, both in the north of the country- was 3,825,222 tons (74.4%), and 383.716 tons (7.4%) corresponding to Peruvian ports -basically Ilo and Matarani, in southern Peru-; the rest went to the Atlantic agreement with the figures collected by the Bolivian authorities in the last report of the Administration of Port Services-Bolivia (ASP-B).

In 2019, of total exports of 5,590,761 tonnes, 3,732,130 were transported through Chilean ports (66.7%) and 605,185 through Peruvian ports (10.8%). Between 2018 and 2019, the flow through Peruvian ports increased by 57.7%.

high school In 2020, due to the confinements of the Covid-19 pandemic, world trade traffic decreased and Bolivian exports dropped to 4.57 million tonnes: the decline affected transit through Chile the most, which fell to 2.9 million tonnes (63.4% of total exports), while that through Peru remained at 0.6 million (13.3%), according to the Bolivian Foreign Trade Agency (IBCE) on its bulletin transport and logistics website. IBCE bulletins show that almost all Bolivian exports are exported by sea, although the journey to shipment involves various means of transport.