area area and adjacent territories [Wikimedia-Commons].

ANALYSIS / Emili J. Blasco

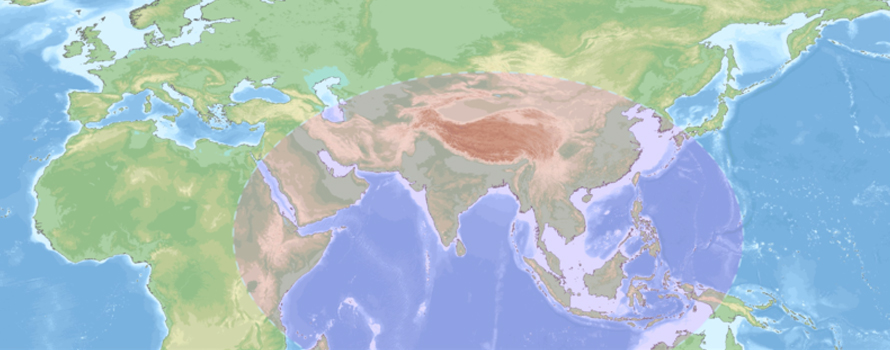

We are witnessing the effective birth of Eurasia. If that word arose as an artifice, to bring together two adjacent, unrelated geographies, today Eurasia is emerging as a reality, in a single geography. The catalyst has been above all China's westward opening: as China has begun to deal with its backside - Central Asia - and has drawn new land routes to Europe, the distances between the margins of Eurasia have also been shrinking. The maps of the Silk Belt and Road Initiative have the effect of first presenting a single continent, from Shanghai to Paris or Madrid. The trade war between Beijing and Washington and Europe's abandonment of the once American umbrella are helping China and Europe to seek each other out.

One consequence of the crossed gaze from the two ends of the supercontinent, whose meeting constructs this new mental map of a continuous territory, is that the world axis has shifted to the Indian Ocean. It is no longer in the Atlantic, as it was when the United States took over the banner of the West from Europe, nor is it in the Pacific, where it had moved with the emerging phenomenon of East Asia. What seemed to be the location of the future, the Asia-Pacific, is giving way to the Indo-Pacific, where China is certainly not losing prominence, but is more subject to the Eurasian balance of power. The irony for China is that in its desire to regain its former position as the Middle Kingdom, its expansionary plans end up giving centrality to India, its veiled nemesis.

Eurasia shrinks

The idea of a shrinking of Eurasia, which reduces its vast geography to the size of our visual field, gaining in its own entity, was expressed two years ago by Robert Kaplan in an essay that he has later collected in his book The Return of framework Polo's World (2018)[1]. It is precisely the revival of the Silk Road, with its historical reminiscences, that has ended up putting Europe and the East on the same plane in our minds, as in a few centuries when, unknown to America, nothing existed beyond the surrounding oceans. "As Europe disappears," says Kaplan in reference letter to Europe's increasingly vaporous borders, "Eurasia is cohesive. "The supercontinent is becoming a fluid, global unit of trade and conflict," he says.

For Bruno Maçães, author of The Down of Eurasia (2018)[2], we have entered a Eurasian era. Despite what might have been predicted just a couple of decades ago, "this century will not be Asian," Maçães assures. Nor will it be European or American, but we are as we were at the end of World War I, when we went from talking about Europe to talking about the West. Now Europe, detached from the United States, according to this Portuguese author, is also becoming part of something bigger: Eurasia.

In view of this movement, both Kaplan and Maçães predict a dissolution of the West. The American emphasizes Europe's shortcomings: "Europe, at least as we have known it, has begun to disappear. And with it the West itself"; while the European points rather to the disinterest of the United States: "One has the feeling that the American universalist vocation is not to guarantee the global preeminence of Western civilization, but to continue as the only global superpower".

Changes the axis of the world

Following the Spanish finding America, the 16th century saw the crowning of a gradual transfer of hegemony and civilization in the world to the West. "The empires of the Persians and Chaldeans had been replaced by those of Egypt, Greece, Italy and France, and now by that of Spain. Here would remain the center of the world," writes John Elliott quoting a writing of the time, by the humanist Pérez de Oliva[3]. The idea of final station was also held when the specific weight of the world was placed in the Atlantic, and then in the Pacific. Today we are once again pursuing this shift towards the West, to the Indian Ocean, perhaps without much encouragement to consider it definitive, even if the turn is completed, the beginnings of which were theorized by the Renaissance.

After all, there have also been shifts in the center of gravity in the opposite direction, if we consider other parameters. In the decades after 1945, the average location of economic activity between different geographies was in the center of the Atlantic. With the turn of the century, however, the center of gravity of economic transactions has been located east of the borders of the European Union, according to Maçães, who predicts that in ten years the midpoint will be on the border between Europe and Asia, and in the middle of the 21st century between India and China, countries that are "destined to develop the largest trade relationship in the world". With this, India "can become the central node between the extremes of the new supercontinent". Moving to one side of the planet, we have arrived at the same point - the Indian Ocean - as in the opposite direction.

Island world

Unlike the Atlantic and the Pacific, oceans that extend vertically from pole to pole, the Indian Ocean spreads out horizontally and, instead of having two shores, has three. This means that Africa, at least its eastern part, is also part of this new centrality: if the speed of navigation brought about by the monsoons has already historically facilitated close contact between the Indian subcontinent and the East African coast, today the new maritime silk routes can further increase exchanges. This and the growing arrival of sub-Saharan migrants in Europe reflect a centripetal phenomenon that even gives rise to talk of Afro-Eurasia. So, as Kaplan points out, referring to the island world as Halford Mackinder once did "is no longer premature". Maçães recalls that Mackinder saw as a difficulty in perceiving the reality of that island world the fact that it was not possible to circumnavigate it completely. Today that perception should be easier, when the Arctic route is opening up.

In the framework of Halford Mackinder's and Nicholas Spykman's complementary theories -verse and reverse- on the Heartland and the Rimland, respectively, any centrality of India has to translate into maritime power. With its access to the interior of Asia Closed by the Himalayas and by an antagonistic Pakistan (it is left with the unique and complex passage of Kashmir), it is at sea that India can project its influence. Like India, China and Europe are also in the Eurasian Rimland, from where all these powers will dispute the balance of power among themselves and also with the Heartland, which is basically occupied by Russia, although not exclusively: in the Heartland there are also the Central Asian republics, which have a special value in the skill for space and resources of a shrinking supercontinent.

Pivot to Eurasia

In this Indo-Pacific, or Greater Indian Ocean region, which stretches from the Persian Gulf and the coasts of East Africa to the second island chain of the Asia-Pacific, the United States has an external role to play. As the island world becomes more cohesive, the U.S. satellite character becomes more pronounced. The grand strategy of the United States then becomes what has been the traditional imperative of the United Kingdom with respect to Europe: to prevent one power from dominating the continent, something that is most easily achieved by supporting one or another continental power to weaken whichever is stronger at the time (France or Germany, depending on the historical period; today Russia or China). Already in the Cold War, the United States tried to prevent the USSR from becoming a hegemon by controlling Western Europe as well. Eurasia enters into a presumably intense game of balance of power, as was the European scenario between the 19th and 20th centuries.

For this reason, Kaplan says that Russia can be contained much more by China than by the United States, just as Washington should take advantage of Russia to limit China's power, as suggested by Henry Kissinger. To this end, the Pentagon should extend its strategic presence in the Western Pacific to the West: if as an external and maritime power it cannot access the continental center of Eurasia, it can take up a position in the very bowels of that great region, which is the Indian Ocean itself.

"If Obama pivoted to Asia, then Trump has pivoted to Eurasia. Decision-makers in the United States seem increasingly aware that the new center of gravity in world politics is neither the Pacific nor the Atlantic, but the Old World between the two," Maçães has written in an essay following his book[4].

|

Image of the official presentation of the Japanese Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy [Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan].

|

Alliances with India

The shift in focus from Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific by the United States was formally expressed in the National Security Strategy published in December 2017, the first of that subject of documents produced by the Trump Administration. Consequently, the United States has renamed its Pacific Command the Indo-Pacific Command.

Washington's strategy, like that of other leading Western countries in the region, especially Japan and Australia, involves a coalition of some subject with India, given India's centrality and as the best way to contain China and Russia.

The desirability of an enhanced relationship with New Delhi was already outlined by Trump during the visit of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Washington in June 2017, and then by then Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in October 2017. The latter's successor, Mike Pompeo, addressed a more defined framework in July 2018, when he announced $113 million in aid for projects aimed at achieving greater connectivity in the region, from digital technologies to infrastructure. The advertisement was understood as the U.S. desire to confront the Silk Belt and Road Initiative launched by China.

The U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy is sometimes presented in association with the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (FOIP), which is the name given by Japan to its own cooperation initiative for the region, already outlined ten years ago by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Both coincide in counting on India, Japan, Australia and the United States as the main guarantors of regional security, but there are two main divergences. One is that for Washington the Indo-Pacific stretches from India's eastern seaboard to the U.S. west coast, while in the Japanese initiative the map runs from the Persian Gulf and the African coast to the Philippines and New Zealand. The other has to do with the way China is perceived: the Japanese proposal seeks Chinese cooperation, at least at the declarative level, while the US purpose is to confront the "risks of Chinese dominance", as stated in the National Security Strategy.

India has also developed its own initiative, presented in 2014 as Act East Policy (AEP), with the aim of promoting greater cooperation between India and Asia-Pacific countries, especially ASEAN. For its part, Australia presented its Policy Roadmap for the region in 2017, which builds on the security already provided by the United States and advocates a continued understanding with the "Indo-Pacific democracies" (Japan, South Korea, India and Indonesia).

Other consequences

Some other consequences of the birth of Eurasia, of different order and importance, are:

-The European Union is not only ceasing to be attractive as a political and even economic project for its neighbors, due to its internal convergence problems, but the reality of Eurasia reduces it to a peninsula on the margins of the supercontinent. For example, the old question of whether or not Turkey is part of Europe loses any interest: Turkey will have a better position on the chessboard.

-The corridors that China wants to keep open towards the Indian Ocean (Myanmar and, above all, Pakistan) are gaining in importance. Without being able to regain the millenary status of Middle Kingdom, China will value even more having the province of Xinjiang as a way of being less slanted on one side of the supercontinent and as a platform for a greater projection towards the interior of the same.

-The U.S. pivot to Eurasia will force Washington to spread its forces over a larger expanse of sea and its shores, with the risk of losing deterrent or intervention power in certain places. Looking after the Indian Ocean may unintentionally lead it to neglect the South China Sea. One way of gaining influence in the Indian Ocean without much effort could be to move the headquarters of the Fifth Fleet from Bahrain to Oman, also a stone's throw from the Strait of Hormuz, but outside the Persian Gulf.

-Russia has traditionally been seen as a bridge between Europe and Asia, and has had some proponents of a Eurasianism that presented Eurasia as a third continent (Russia), with Europe and Asia on either side, and reserved the name Greater Eurasia for the supercontinent. As the supercontinent shrinks, Russia will benefit from the greater connectivity between one end and the other and will be more on top of its former Central Asian republics, although these will have contact with a greater issue of neighbors.

(1) Kaplan, R. (2018) The Return fo framework Polo's World. War, Strategy, and American Interests in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Random House

(2) Maçães, B. (2018) The Dawn of Eurasia. On the Trail of the New World Order. Milton Keynes: Allen Lane

(3) Elliott, J. (2015) The Old World and the New (1492-165). Madrid: Alianza publishing house

(4) Maçães, B. (2018). Trump's Pivot to Eurasia. The American Interest. 21 August 2018.