Bolivia has consolidated its role in distributing Peruvian cocaine and its own cocaine for consumption in South America and export to Europe.

-

In 2019, the government of Martin Vizcarra eradicated 25,526 hectares of coca cultivation, half of the estimated total extension of plantations.

-

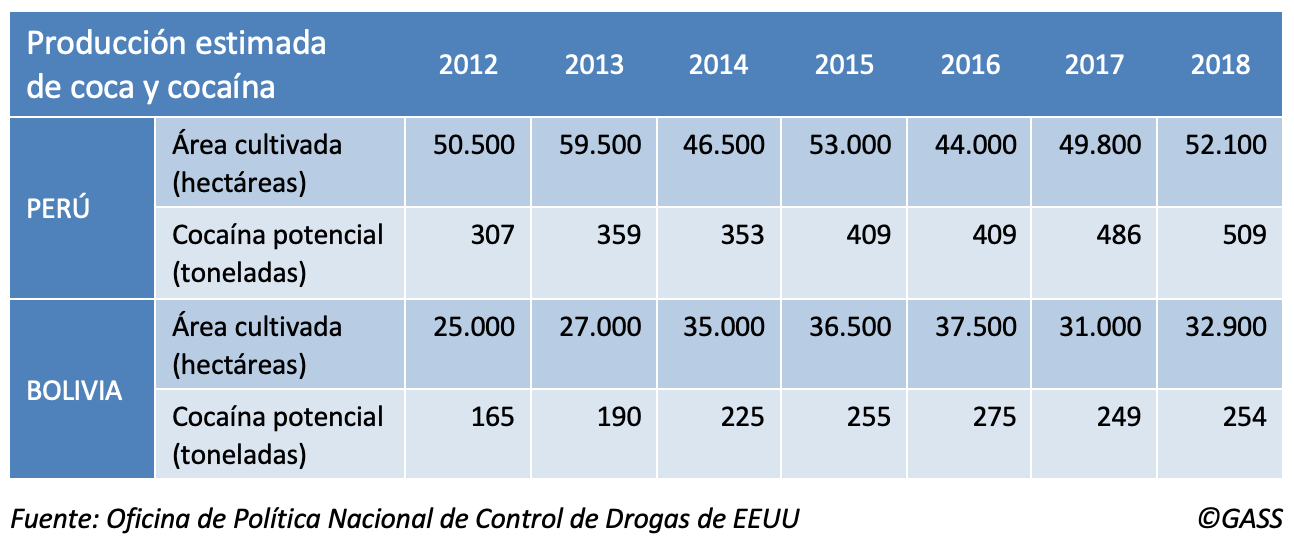

Peru had a record potential cocaine production of 509 tons in 2018; Bolivia's was 254, one of the historically highest, according to US

-

The US accused Morales towards the end of his term of office of having "manifestly failed" to fulfill his international obligations with his 2016-2020 counter-narcotics plan.

▲ Coca eradication operation in Alto Huallaga, Peruproject CORAH].

report SRA 2020 / Eduardo Villa Corta [PDF version]

MAY 2020-Since Peru's national plans against coca cultivation began in the 1980s, eradication campaigns have never reached what is known as the VRAEM (Valley of the Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro Rivers), a difficult-to-access area in the center of the southern half of the country. Organized crime operates in this area, especially the remnants of the old Shining Path guerrillas, now dedicated to drug trafficking and other illicit businesses. The area is the source of 64% of the country's potential cocaine production. Peru is the second largest producer in the world, after Colombia.

The government of President Martin Vizcarra carried out in 2019 a determined policy of suppression of illicit crops. The eradication planproject Especial de Control y Reducción del Cultivo de Coca en el Alto Huallaga or CORAH) was applied last year to 25,526 hectares of coca crops (half of the existing ones), of which 750 would have corresponded to the VRAEM (operations took place in the areas of Satipo, Tambo River and Alto Anapati, in the Junín region).

These actions should translate, when the figures for 2019 are presented, into a reduction in total coca cultivation and potential cocaine production, thus breaking the increase experienced in recent years. According to the latest International Narcotics Control Strategyreport (INCSR) of the US State department , which closely follows this illicit activity in the countries of the region, in 2018 there were 52,100 hectares of coca in Peru (compared to 44,000 in 2016 and 49,800 in 2017), whose extension and quality of cultivation could generate a record production of 509 tons of cocaine (compared to 409 in 2016 and 486 in 2017). Although in 2013 there was a larger cultivated area (59,500 hectares), then the cocaine potential stood at 359 tons.

From Peru to Bolivia

This increase in recent years in the generation of cocaine in Peru has consolidated Bolivia's role in the trafficking of that drug, since in addition to being the third largest producer country in the world (in 2018 there were 32,900 hectares cultivated, with a potential production of 254 tons of narcotic substance, according to the US), it is a transit zone for cocaine of Peruvian origin.

The fact that only about 6% of the cocaine reaching the United States comes from Peru (the rest comes from Colombia), indicates that most of the Peruvian production goes to the growing market in Brazil and Argentina and to Europe, and therefore its natural exit point is through Bolivia. Thus, Bolivia is considered a major "distributor".

Some of the drugs arrive in paste form and are refined in Bolivian laboratories. The goods are smuggled into Bolivia using small planes, which sometimes fly at less than 15 meters above the ground and drop the cocaine packages in uninhabited rural areas; they are then picked up by elements of the organization. The movement is also carried out by road, with the drugs camouflaged on cargo roads, and to a lesser extent using Lake Titicaca and other waterways connecting the two countries.

Once across the border, the drugs from Peru, along with those produced in Bolivia, travel to Argentina and Chile, especially through the Bolivian city of Santa Cruz and the Chilean border crossing of Colchane, or enter Brazil -- directly or through Paraguay, using for example the crossing between the Paraguayan town of Pedro Juan Caballero and the Brazilian town of Ponta Pora -- for consumption in South America's largest country, whose Issue has climbed to second place in the world, or to reach international ports such as Santos. This port, which is Sao Paulo's outlet to the sea, has become the new hub of the global narcotics trade, from which almost 80% of Latin America's drugs leave for Europe (sometimes via Africa).

Production in Bolivia has been growing again since the middle of the last decade, although in the Bolivian case there is a notorious difference between the often divergent figures offered by the United States and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Both estimates agree that there was a previous decline, attributed by the La Paz government to the so-called "rationalization of coca production", which reduced production by 35% and adjusted cultivation areas to those permitted by law, in a country where traditional uses of coca are allowed.

However, the Coca Law promoted in 2017 by President Evo Morales (his political degree program originated in the coca growers' unions, whose interests he later continued to defend) protected an extension of production, raising the permitted hectares from 12,000 to 22,000. The new law covered an increase that was already occurring and encouraged greater excesses that have far exceeded the Issue required for traditional uses, which programs of study by the European Union put at less than 14,700 hectares. In fact, the UNODC estimated in its 2019 report that between 27% and 42% of the coca leaf grown in 2018 was not sold in the only two local markets authorized for it, indicating that at least the rest was destined for cocaine production.

For 2018, the UNODC determined a production of 23,100 hectares, in any case above what is allowed by law. US data speak of 32,900 hectares, which was an increase of 6% over the previous year, and a potential cocaine production of 254 tons (up 2%).

Sixty-five percent of Bolivian production takes place in the Yungas area, near La Paz, and the remaining 35% in Chapare, near Cochabamba. In the latter area, crops are expanding, encroaching on the Tipnis natural reservation . The park, which goes deep into the Amazon, suffered in 2019 important fires: intentional or not, the annihilated tropical vegetation could give way to clandestine coca plantations.

After Morales

The 2020 US State department report highlights the increased anti-drug commitment of the Bolivian authorities who in November 2019 succeeded the Morales government, which had maintained "inadequate controls" over coca cultivation. The US considers that Morales' 2016-2020 anti-drug plan "prioritized" actions against criminal organizations rather than combating coca growers' production that exceeded the permitted Issue . Shortly before leaving office in September, Morales was singled out by the US for having "manifestly failed" to comply with international obligations subject drug control.

According to the US, the transitional government "has made important strides in drug interdiction and extradition of drug traffickers". This increased control by the new Bolivian authorities, together with the determined action of the Vizcarra government in Peru, should lead to a reduction in coca cultivation and cocaine production in both countries, and therefore in its export.