The United States continues to monitor the innovation of methods that could also be used to introduce terrorist cells or even weapons of mass destruction.

In the last ten years, the proliferation of submersible and semi-submersible vessels, which are difficult to detect, has accounted for a third of drug shipments from South America to the United States. The incorporation of GPS systems by the cartels also hampers the global counter-narcotics fight. A possible use of these new methods for terrorist purposes keeps the United States on its toes.

▲ Narco-submarine found in the jungle of Ecuador in 2010 [DEA].

article / Marcelina Kropiwnicka [English version].

Drug trafficking to the major consumer markets, especially the United States and Europe, is particularly innovative: the magnitude of the business leads to attempts to overcome any barriers put up by the States to prevent its penetration and distribution. In the case of the United States, where the illicit arrival of narcotics dates back to the 19th century - from opium to marijuana and cocaine - continued efforts by the authorities have succeeded in intercepting many drug shipments, but traffickers are finding new ways and methods to bring a significant Issue of narcotics into the country.

The most disturbing method in the last ten years has been the use of submersible and semi-submersible vessels, commonly referred to as narco-submarines, which make it possible to transport several tons of drugs - five times more than a fishing boat - while evading coast guard surveillance [1]. Satellite technology has also led traffickers to leave drug loads at sea, which are then picked up by pleasure boats without arousing suspicion. These methods are reference letter in recent reports by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the US anti-narcotics agency.

Through the waters of Central America

For many years, the usual way to transport drugs leaving South America for the United States has been by fishing boats, speedboats and light aircraft. Advances in airborne detection and tracking techniques have pushed drug traffickers to look for new ways to get their loads north. Hence the development of narco-submarines, whose issue, since a first interception in 2006 by US authorities, has seen a rapid progression.

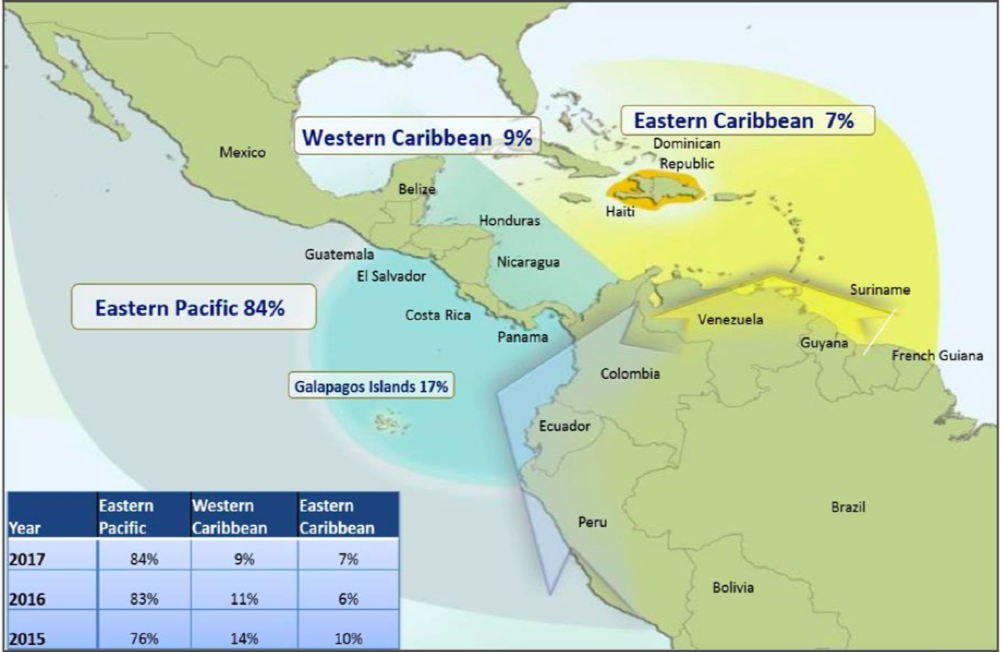

This means of transport is one of the reasons why, since 2013, trafficking along the drug route from Colombia (the country that produces 93% of the cocaine consumed in the US) to Central America and Mexico, from where the shipments are smuggled into the US, has increased by 10%. According to the DEA, this corridor now accounts for an estimated 93% of the movement of cocaine from South America to North America, compared to 7% of the route that seeks the Caribbean islands (mainly the Dominican Republic) to reach Florida or other parts of the US coast.

For some time, a rumor spread among the US Coast Guard that drug cartels were using narco-submarines. Without having seen one so far, the agents gave it the name of 'Bigfoot' (as an alleged ape-like animal known to inhabit the forests of the U.S. Pacific).

The first sighting occurred in November 2006, when a U.S. Coast Guard patrol boat spotted a blurred shape in the ocean about 100 miles off the coast of Costa Rica. When the agents approached, they discovered three plastic tubes emerging from the water, which came from a submersible vessel making its way six feet below the surface. Inside they found three tons of cocaine and four men armed with an AK-47 rifle. The Coast Guard christened it 'Bigfoot I'.

Two years later there would be a 'Bigfoot II'. In September 2008, a U.S. Navy frigate on coast guard duty apprehended a similar craft 350 miles from the Mexico-Guatemala border. The crew consisted of four men and the cargo was 6.4 tons of cocaine.

By then, US authorities estimated that more than 100 submersibles or semi-submersibles had been manufactured. In 2009 they estimated that they were only being able to stop 14% of shipments and that this mode of transport supplied at least a third of the cocaine reaching the US market. The navies of Colombia, Mexico and Guatemala have also seized some of these narco-submarines, which in addition to being located in the Pacific have also been detected in the Caribbean and the Atlantic. Manufactured by hand in the jungle, perhaps the most striking episode was that one of them was found in the interior of Ecuador, in the waters of a river.

Their technical innovation has often surprised counter-narcotics officials. Many of these self-propelled narco-submarines are as long as fifteen meters, are made of synthetic materials and fiberglass, and have been designed to reduce radar or infrared detection. Some models have also been fitted with GPS navigation systems so that fuel can be refueled and food can be delivered to rendezvous along the route.

GPS Location

The development and generalization of GPS has also served drug traffickers to introduce further innovations. One procedure, for example, has been to fill a torpedo-shaped container with drugs - like a submersible, but this time unmanned - attached to a buoy and a signal transmitter. The container can hold up to seven tons of cocaine and is attached to the bottom of a ship by a cable. If the ship is intercepted, it can simply drop the container deeper, only to be retrieved by another vessel thanks to the satellite locator. This makes it extremely difficult for the authorities to capture the drugs and arrest the traffickers.

The GPS navigation system is also used to deposit drug loads at points in U.S. territorial waters, where they can be picked up by pleasure boats or a small group of people without arousing suspicion. The package containing the cocaine is coated with several layers of material and then the whole thing is waterproofed with a foam subject . The package is placed inside a canvas bag which is deposited at the bottom of the sea to be later retrieved by other people.

As the DEA notes in its 2017 report , "this demonstrates how drug trafficking organizations have evolved their methods for conducting cocaine transactions using technology." And it quotation the example of organizations that "transport kilos of cocaine in waterproof packages to a predetermined location and attach it to the ocean floor for later removal by other members of the organization who have GPS tracking," which "allows members of drug trafficking organizations to compartmentalize their work, separating those who do the maritime transport from the onshore distributors."

|

Cocaine journey from South America to the United States in 2017 [DEA].

|

Terrorist risk

The possibility that these very difficult to detect methods could be used to smuggle weapons or could be part of terrorist operations is of concern to U.S. authorities. Retired Vice Admiral James Stravidis, former head of the U.S. Southern Command, has warned of the potential use of submersibles especially "to transport more than just narcotics: the movement of cash, weapons, violent extremists or, at the worst end of the spectrum, weapons of mass destruction."

Rear Admiral Joseph Nimmich also referred to this risk when, as commander of the Joint Interagency work South, he was confronted with the emergence of submersibles. "If you can carry ten tons of cocaine, you can carry ten tons of anything," he told The New York Times.

According to this newspaper, the stealthy development of homemade submarines was first developed in Sri Lanka, where the Tamil Tiger rebel group used them in their confrontation with government forces. "The Tamils will go down in history as the first terrorist organization to develop underwater weapons," the Sri Lankan Ministry of Defense claimed. In 2006, as the NYT states, "a Pakistani and a Sri Lankan provided the Colombians with plans to build semi-submersibles that were fast, quiet and made of cheap, commonly available materials.

Despite this origin, ultimately written request related to Tamil rebels, and the terrorist potential of submersibles used by drug cartels, Washington has reported no evidence that the new drug transportation methods developed by organized crime groups are being used by extremist actors of a different stripe. Nonetheless, the U.S. is keeping its guard up given the high rate of shipments arriving undetected.

[1] REICH, S., & Dombrowski, P (2017). The End of Grand Strategy. US Maritime Pperations in the 21st Century. Cornell Univesity Press. Ithaca, NY. Pp. 143-145.