Ruta de navegación

Blogs

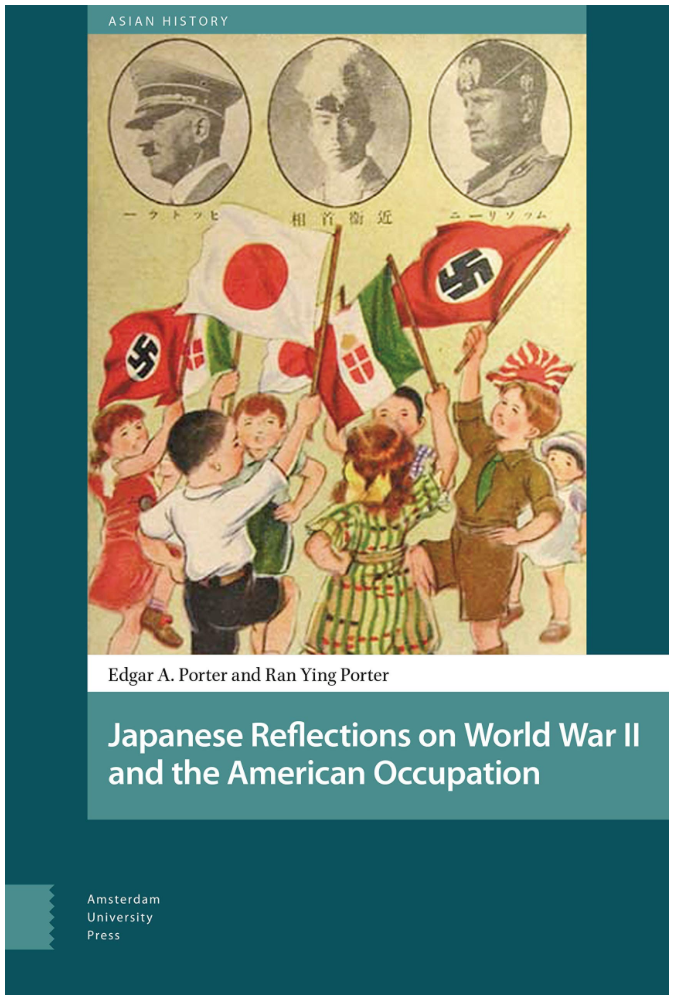

[Edgar A. Porter & Ran Yin Porter, Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation. Amsterdam University Press. Amsterdam, 2017. 256 p.]

REVIEW / Rut Natalie Noboa Garcia

World War II has provided much inspiration for an entire genre of literature. However, few works fail to capture Asian perspectives on the beginning, development, end, and consequences of World War II. Additionally, the attitude and outlooks of defeated parties are often left out of popularized discussions of conflicts. Because of these two factors, Japanese perspectives during the war and occupation have often served as only minor discussions in World War II literary work.

World War II has provided much inspiration for an entire genre of literature. However, few works fail to capture Asian perspectives on the beginning, development, end, and consequences of World War II. Additionally, the attitude and outlooks of defeated parties are often left out of popularized discussions of conflicts. Because of these two factors, Japanese perspectives during the war and occupation have often served as only minor discussions in World War II literary work.

This sets the stage for Edgar A. Porter and Rin Ying Porter's Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation, which presents the experiences of ordinary Japanese citizens during the period. The book specifically focuses on the rural Oita prefecture, located on the eastern coast of the island of Kyushu, a crucial yet critically unacknowledged place in Japan's role in World War II. Hosting the Imperial Japanese Navy base that served as the headquarters for the Pearl Harbor attack, being the hometown of the two Japanese representatives that signed the terms of surrender at the USS Battleship Missouri, serving as the place for the final kamikaze attack against the United States, and providing much of Japan's foot soldiers for the conflict, Oita is ripe with unchronicled, raw, and diverse accounts of the Japanese experience.

The collective stories of the 43 interviewees, who lived through the war and occupation present the varied perspectives of soldiers, sailors, and pilots, who are often at the centre of war discussions and experiences, but also that of students, teachers, nurses, factory workers and more, providing a multidimensional portrayal of the period.

The book begins with the early militarization of the Oita prefecture, specifically in Saiki, the location for one of the most crucial instructions for the Japanese Imperial Navy. This first chapter features the perspectives of young Saiki citizens raised during the period who still see the Pearl Harbor attack with a conflicted yet enduring pride, setting the stage for following interesting discussions on Japanese post-war sentiment.

Another important aspect addressed by the Porters in this work is the mass censorship and indoctrination that took place in Japan during the war period. During this time, average censorship and military-based education helped to obscure the actual happenings of the conflict, particularly in its earlier years, as well as rallying the population in support for the Japanese navy. As well as presenting censored portrayals of the war itself, local Oita editorials both highlighted and encouraged public support for the war and the glorification of death and martyrdom. This indoctrination is also acknowledged by the Porters in relation to traditional Japanese Shinto beliefs on the emperor, specifically his divine origins. Japan's average portrayals of the conflict concerning the state and emperor as well as its moral education curriculum feed into each other, applying moral pressure to the support of war efforts.

Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation also provides particularly interesting insights on East Asian regionalism, particularly from the perspective of Imperial Japan, which viewed itself as an "older brother leading the newly emerging members of the Asian family towards development" and promoted the idea that the Japanese were racially superior to other Asian ethnic groups. The first-hand accounts of many of the atrocities committed by Japanese in cities such as Nanjing and Shanghai as well as their glorification by the Japanese press add to the book's depth and relevance.

As the war approached an end, conflict reached Oita. The targeting of civilians and the bombing of factories during American air raids lowered Oita morale. Continued air raids on Oita City, the prefecture's capital city, rapidly fueled the region's fear and resentment towards American soldiers.

In conclusion, Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation manages to present important first-hand accounts of Japanese life during one of the most consequential moments in modern history. The impact of these events on current Japan is particularly interesting when it comes to Japanese culture, especially when it comes to the glorification of war in Japanese education as well as the rising tide of Japanese nationalism.

![Farewell of Espérance Nyirasafari (left) as minister of Gender and Family Promotion, in Rwanda's capital in 2018 [Rwanda's Gov.] Farewell of Espérance Nyirasafari (left) as minister of Gender and Family Promotion, in Rwanda's capital in 2018 [Rwanda's Gov.]](/documents/10174/16849987/rwanda-blog.jpg)

▲ Farewell of Espérance Nyirasafari (left) as minister of Gender and Family Promotion, in Rwanda's capital in 2018 [Rwanda's Gov.]

ESSAY / María Rodríguez Reyero

South Africa is ranked 17th in the World Economic Forum's 2020 Global Gender Gap Index[1] (a two place increase from 2019), while Rwanda is ranked 9th (a three place decline from the previous year). Interestingly, Spain is ranked 8th (a major gain of 11 places in one year). Since 2018, Spain has made a gain of 21 places, which is only rivaled by countries like Madagascar (22), Mexico and Georgia (25) and Ethiopia (35).

Regarding political participation and governance in the last decade, the number of African women in ministerial posts has tripled. African women already account for 22.5% of parliamentary seats, a similar percentage to that of Europe (23.5%) and higher than that of the US (18%). However, does the increase in female participation in high political positions lead to a real improvement in the lives of other women? Or is female participation only a façade?

This study's main aim is to explore the impact that women's participation in politics has on the circumstances of the rest of women in their countries. The study is based on secondary research and quantitative data collection and will objectively analyze the situation in Spain, Rwanda, and South Africa and draw pertinent conclusions.

Rwanda

From April to July 1994, between 800,000 and one million ethnic Tutsis were brutally killed during a 100 day killing spree perpetrated by Hutus [2]. After the genocide, Rwanda was on the edge of total collapse. Entire villages had been destroyed, and social cohesion was in tatters. Yet, this small African country has made a remarkable economic turnaround since the genocide. The country now boasts intra-regional trade and has positioned itself as an attractive destination for foreign investment, being a leading country in the African economy. Rwanda's economy appears to be thriving, with annual GDP growth averaging 7.76% between 2000 and 2019, and "growth expected to continue at a similar pace over the next few years" according to a recent study of World Finance. [3] About 70% of the survivors of the fratricidal struggle between Hutus and Tutsis are women, and thus women play a role of utmost importance in the recovery of Rwanda.[4]

The Rwandan genocide ended with the deaths of one million people and the rape of more than 200,000 women. [5] Women were the clear losers of the conflict, yet the conflict also enabled women to become the main economic, political and social engine of Rwanda during its recovery from the war. Roles traditionally assigned to men were assigned to women, which turned women into more active members of society and empowered them to fight for their rights. The main area where this shift has been felt is in politics, where gender parity reaches its highest level thanks to Rwanda's continued commitment to equal representation. This support has led the proportion of women in the Rwandan National Parliament to even exceed that of men in the lower house, which consists of 49 women out of a total of 89 representatives.[6]

The body responsible for coordinating female protection and empowerment is the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion, promoter of the National Gender Policy. The minister of Gender until 2018 was Espérance Nyirasafari. Nyirasafari was responsible for several main changes in Rwandan society including the approval of laws against gender-based violence. She now serves as one of two Vice Presidents of the senate of Rwanda.

Consequently, Rwanda illustrates African female advancement. In addition to currently being the world's leading country in female representation in Parliament, (in which women hold nearly 60% of the seats), Rwanda reached the fourth highest position in the World Economic Forum's gender gap report. The only countries that came close in this respect were Namibia and South Africa.

The political representation of women in Rwanda has led to astonishing results in other areas, notably education. Rwanda's education system is considered one of the most advanced in Africa, with free and compulsory access to primary school and the first years of high school. About 100% of Rwandan children are incorporated into primary school and 75% of young people ages 15+ are literate. However, high school attendance is significantly low, counting with just 23% of young people, of which women represent only 30%. [7] Low high school attendance is mainly due to the predominance of rural areas in the country, where education is more difficult to access, especially for women, who are frequently committed to marriage and the duties of housework and family life from a very young age. Despite the growing data and measures established, education is in reality very hard to achieve for women, who are mostly stuck at home or committed to other labor.[8]

Regarding the legislative measures put in place to achieve gender equality and better conditions and opportunities for women, Rwanda does not score high. Despite being one of the most advanced countries in gender equality, currently, no laws exist to ensure equal pay or non-discrimination in the hiring of women, according to WEF's 2019 report, even if some relevant legal measures have been effectively been put into practice since the ratification of the 2003 Constitution, which demonstrates the progress on gender equality in Rwanda.

The Constitution also argues that the principle of gender equality must prevail in politics and that the list of members of the Chamber of Deputies must be governed by this equitable principle. The law on gender violence passed in 2008 is proof of national commitment to women's rights, as it recognizes innovative protections such as the prohibition of spousal rape, three months of compulsory maternity leave (even some Western countries such as the United States lack this protection) or equal rights in inheritance process regardless of gender.[9]

Finally the labor law passed in 2009 establishes numerous protections for Rwandan women, such as receiving the same salary as their male colleagues or the total prohibition of any gesture of sexual content towards them.

Some of the most relevant progress made in Rwanda are the reduction of the percentage of women in extreme poverty from 40% in 2001 to 16.3% in 2014, and the possession of land by 26% of women personally and 54% in a shared way with their husbands. [10] Thanks to the work and commitment of female politicians, Rwandan women today enjoy inalienable rights which women in many other countries can only dream of. 11] This ongoing egalitarian work has paid off: Rwanda is as mentioned above the 9th country in the world with a smaller gender gap, only behind Iceland, Nicaragua, Finland, Sweden, and Norway. In the annual study of the World Economic Forum, only five countries (including Rwanda, the only African) have surpassed the 50% barrier in terms of reducing the gender gap in politics. Likewise, the gender parity in economic participation that Rwanda has achieved is of great relevance, which has made it the first country in the world to include women in the world of work and equal economic remuneration. Rwanda is a regional role model in terms of egalitarian legislation.[12]

South Africa

According to IMF and World Bank latest data, South Africa currently is the second most prosperous country of the whole continent, only surpassed by Nigeria. The structure of its economy is that of a developed country, with the preeminence of the services sector, and the country stands out for its extensive natural resources, thus being considered one of the largest emerging economies nowadays. South Africa also has a seat in the BRICS economy block (with Brazil, Russia, India, and China) and is a member of the G20.

Despite its economic position, the country is also home to great inequality, largely bequeathed in its history of racial segregation. According to the New York Times, the post-apartheid society had to face great challenges: it had to "re-engineer an economy dominated by mining and expand into modern pursuits like tourism and agriculture while overcoming a legacy of colonial exploitation, racial oppression, and global isolation - the results of decades of international sanctions."[13] However, what is the role of women in this deep transformation? Has their situation improved or are they the new discriminated ones?

South Africa continues to lead the way in women's political participation in the region with 46% of women in the House of Assembly and provincial legislatures and 50% of women in the cabinet after the May 2019 elections. All the speakers in the national and provincial legislatures are women. Women parliamentarians rose from 40% in 2014 to 46% in 2019.

Rwanda, Namibia and South Africa are ranked in the top 20 countries in reducing the gender gap. On the other hand, South Africa does have established legislation about equality in salaries, but not in non-discrimination in the hiring process according to the data collected by the World Economic Forum in January 2020.

South Africa is writing a new page in its history thanks to the entry of Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma (she was elected in 2012 president of the African Union Commission becoming the first woman to lead this organisation, and currently serves as Minister of Planning, Monitoring, and Evaluation in South Africa's Government) and other women, such as Lindiwe Nonceba Sisulu (minister of International Relations and Cooperation until 2019) into the political competition.

Subsequently, women have always been involved in political organisations, as well as in the trade union movement and other civil society organisations. Although evolving in a patriarchal straitjacket due to the social role women had assigned, they don't wait for "the authorization of men" to claim their rights. This feminine tradition of political engagement in South Africa has resulted the writing of a protective Constitution for women in a post-apartheid multiracial and supposedly non-sexist context.

However, this has not led to an effective improvement in the real situation of women in the country. According to local average data,[14] a woman dies every eight hours in South Africa because of gender violence and, according to 2016 government statistics, one in five claims to have suffered at some time in her life. Besides, in South Africa, about 40,000 rapes are reported annually, according to police data, the vast majority reported by women. These figures lead South Africa's statistics agency to estimate that 1.4 out of every thousand women have been raped, which places the country with one of the highest rates of this type in the world.[15]

Spain

After a cruel civil war, followed by 36 years of dictatorship, Spanish society was looking forward to a change, and thus the democratic transition took place, transforming an oppressed country into the Spain we nowadays know. On many occasions, history tends to forget the 27 women, deputies and senators of the 1977 democratic legislature who were architects of this political change (divorce law, legalize the sale of contraceptives, participate in the drafting of the Constitution of 1978, amongst others). These women also having an active role in politics, something unusual and risky for a woman at that time (without rights as basic as owning property or opening a bank account during the dictatorship). It is clear that women played a crucial role in the transformation of Spanish society, but has it really been effective?

Spain's new data since the establishment of a new government in January 2020 is among the top 4 European countries with the highest female proportion: behind Sweden (with 47.4%), France (47.2%) and Finland (45.8%), according to the latest data published by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). [16] After the last elections in November, Spain is placed in tenth place in the global ranking. Ahead, there are Rwanda (with 61.3%), Cuba (53.2%), Bolivia (53.1%), Mexico (48.2%) and others such as Grenada, Namibia, Sweden, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, according to data published by the World Bank. Of the 350 congress deputies, 196 are men and 154 are women, meaning that 56% of the members of the House of Representatives are men while 44% are women.

In Spain, also almost every child gets a primary education according to OECD but almost 35% of Spanish young people do not get a higher education. Of those who do go to university nearly 60% of all the students are women. They also get better grades and take on average less time to graduate than men but are less likely to hold a power position: according to PwC Spain last data, only a 19% of all directive positions are held by women, 11% of management advice are women and less than a 5% are women in direction or presidency of Spanish enterprises. This is since at least 2.5 million women in Spain cannot access the labor market because they have to take care of family care. Among men, the figure is reduced to 181,000. The data has been given by the International Labor Organization (ILO). The study also revealed that women in Spain perform 68% of all unpaid care work, dedicating twice as much time as men. About 25% of inactive women in Spain claim that they cannot work away from home because of their family charges. This percentage is much higher than those of other surrounding countries, such as Portugal (13%) or France (10%) and the European average. It is also much larger than that of Spanish men who do not work for the same reason (3%).

Regarding gender-based violence, even if Spain has since 2004 an existing regulation to severely punish it, in the year 2019 a total of 55 women have been killed by their partners or ex-partners, the highest death toll since 2015, with a total of 1,033 since they began to be credited in 2003, according to the balance of the Government Delegation for Gender Violence last data.

Conclusion

To sum up, even if African countries such as Rwanda and South Africa have more women representation and are doing well by-passing laws and measures, due to cultural reasons such as a more ingrained patriarchal society, community interventions, family pressure or the stigma of single mothers, gender equality is more difficult in Africa. Culture, in reality, makes it more difficult to be effective, whereas in Spain the measures implemented, even if they are apparently less numerous, are more effective when it comes to creating institutions that protect women. Women in Africa usually depend a lot on their husbands; they very often suffer in silence not to be left alone without financial support, a situation that in Spain has been tacked without problems.

It is not so much a legislative issue but a cultural one: in Spain, if a woman suffers gender violence and reports it, it is more likely that she would be offered government's help (monetary help, job opportunities...) in order to start a new life, and she most certainly will not be judged by society due to her circumstances. Whereas in South Africa for example, a UN Women rapporteur estimated that only one in nine rapes were reported to the police and that this number was even lower if the woman was raped by a partner, this mainly being due to the social stigma still present nowadays. In Rwanda, a 2011 report from the Rwandan Men's Resource Centre said 57% of women questioned had experienced violence from a partner, while 32% of women had been raped by their husbands, this crime being admitted by only 4% of men, as rape in marriage is seen as a normal situation due to cultural reasons: women still depend somehow on their husbands, and family is the center of society, so it must not be broken.

In numerous occasions, in African countries justice is taken at a different level, in order not to disturb the social and familial order; frequently, rape or gender violence is tackled amongst the parties by negotiating or by less traditional justice systems such as community systems like Gacaca court in Rwanda (a social form of justice designed to promote communal healing, massively used after Rwandan genocide),[17] something unbelievable in Spain, where according to official data from Equality Ministry, last year more than 40.000 reports for gender violence were heard by courts.[18]

In regard to inequality and according to the latest IMF studies, closing the gender gap in employment could increase the GDP of a country by 35% on average, of which between 7 and 8 percentage points correspond to increases in productivity thanks to gender diversity. Having one more woman in senior management or on the board of directors of a company raises the return on assets between 8 and 13 basis points. Consequently, we could state that, as shown by the data (not only those provided by the IMF, but the evident improvements that have taken place throughout this decade in Spain, Burundi, Rwanda, and South Africa) the presence of women both in top management positions and above all, in politics and governance does lead to a real improvement in the rights and lifestyles of the rest of the women, and a substantial improvement of the country as a whole.

However, after their arduous and tricky climb to the top, women inherit a political system which is difficult, if not almost impossible, to change in a few years. Furthermore, the question of the application of laws, when they exist, by the judicial system is a huge challenge in all states as well as making effective all the measures for the reduction of gender inequality. This supposes such a great challenge, not only for these women but also for the whole society, as having arrived where we are.

[1] World Economic Forum (December 2020), The Global Gender Gap Report 2020. World Economic Forum. Accessed 14/02/2020

[2] Max Roser and Mohamed Nagdy (2020),"Genocides". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Accessed 14/02/202

[3] Natalie Keffler (2019), 'Economic growth in Rwanda has arguably come at the cost of democratic freedom', World Finance. Accessed 14/02/2020

[4] Charlotte Florance (2016), 22 Years After the Rwandan Genocide. Huffpost. Accessed 14/02/2020

[5] Violet K. Dixon (2009), A Study in Violence: Examining Rape in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. Inquires journal. Accessed 14/02/2020

[6] Inter-parliamentary Union (2019), 'Women in national Parliaments'. IUP. Accessed 14/02/2020

[7] World Bank (2019), The World Bank in Rwanda. World Bank. Accessed 14/02/2020

[8] Natalie Keffler (2019), 'Economic growth in Rwanda has arguably come at the cost of democratic freedom', World Finance. Accessed 14/02/2020

[9] Tony Blair (2014), '20 years after the genocide, Rwanda is a beacon of hope'. The Guardian. Accessed 14/02/20

[10] Antonio Cascais (2019), 'Rwanda - real equality or gender-washing?' DW. Accessed 14/02/2020

[11] Álex Maroño (2018), 'Rwanda, a feminist utopia?' The World Order. Accessed 14/02/2020

[12] Alexandra Topping (2014), 'The genocide Conflict and arms Rwanda's women make strides towards equality 20 years after the genocide.' The Guardian. Accessed 14/02/2020

[13] Peter S. Goodman (2017), 'End of Apartheid in South Africa? Not in Economic Terms.' The New York Times Site. Accessed 14/02/2020

[14] Gopolang Makou (2018), 'Femicide in South Africa: 3 numbers about the murdering of women investigated.' Africa Check. Accessed 14/02/2020

[15] British Broadcasting Corporation (2019), 'Sexual violence in South Africa: 'I was raped, now I fear for my daughters'. BBC News. Accessed 14/02/2020

[16] European Institute for Gender Equality (2019).Gender Equality Index. EIGE. Accessed 14/02/2020

[17] Gerd Hankel (2019), 'Gacaca Courts', Oxford Public International Law. Accessed 14/02/2020

[18] high school de la mujer (2016), 'Estadísticas violencia de género.' Spanish Ministry of Equality. Accessed 14/02/2020

27% of Latin America's total private wealth is held in territories that offer favourable tax treatment.

Latin America is the world region with the highest percentage of private offshore wealth. The proximity of tax havens, in various countries or island dependencies in the Caribbean, can facilitate the arrival of this capital, some of which is generated illicitly (drug trafficking, corruption) and all of which evades national tax institutions with little supervisory and coercive force. Latin America lost 335 billion dollars in taxes in 2017, which represented 6.3% of its GDP.

![Caribbean beach [Pixabay]. Caribbean beach [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/paraiso-fiscal-blog.jpg)

▲ Caribbean beach [Pixabay].

article / Jokin de Carlos Sola

The natural wealth of Latin American countries contrasts with the precariousness of the economic status of a large part of their societies. Lands rich in oil, minerals and primary goods sometimes fail to feed all their citizens. One of the reasons for this deficiency is the frequency with which companies and leaders tend to evade taxes, driving capital away from their countries.

One of the reasons for the tendency to evade taxes is the large size of the Economics underground and the shortcomings of states in implementing tax systems. Another is the nearby presence of tax havens in the Caribbean, which have historically been linked to the UK. These territories with beneficial tax characteristics have attracted capital from the continent.

History

The history of tax evasion is a long one. Its relationship with Latin America and the British Caribbean archipelagos, however, has its origins in the fall of the British Empire.

From 1945 onwards, Britain gradually began to lose its colonial possessions around the world. The financial effect was clear: millions of pounds were lost or taken out of operations across the empire. To cope with this status and to be able to maintain their global financial power, the bankers in the City of London thought of creating fields of action outside the jurisdiction of the Bank of England, from where bankers from all over the world (especially Americans) could also operate in order to avoid their respective national regulations. A new opportunity then arose in the British overseas territories, some of which did not become independent, but maintained their links, albeit loose, with the United Kingdom. This was the case in the Caribbean.

In 1969 the Cayman Islands created the first banking secrecy legislation. It was the first overseas territory to become a tax haven. From offices established there, City banks built up networks of operations unregulated by the Bank of England and with little local oversight. Soon other Caribbean jurisdictions followed suit.

Tax havens

The main tax havens in the Caribbean are British Overseas Territories such as the Cayman Islands, the Virgin Islands and Montserrat, or some former British colonies that became independent, such as the Bahamas. These are islands with small populations and a small Economics . Many of the politicians and legislators in these places work for the British financial sector and ensure secrecy within their territories.

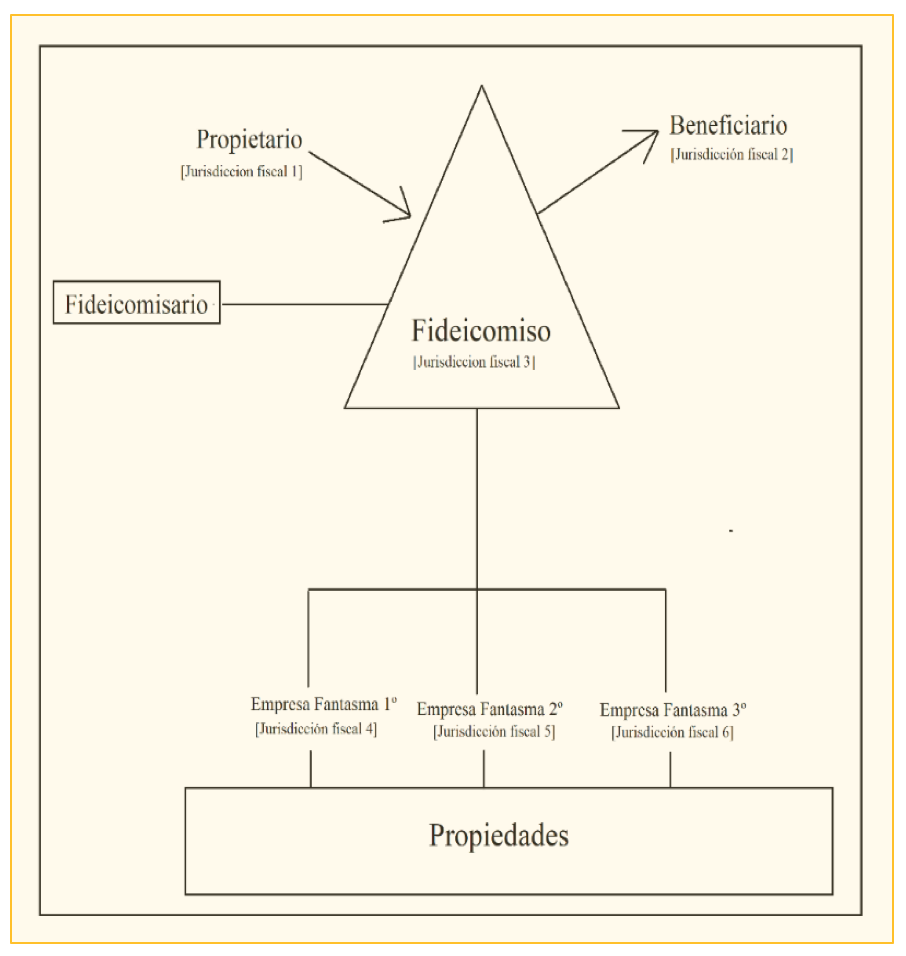

Unlike other locations that can also be considered tax havens, the British-influenced islands in the Caribbean offer a second level of secrecy in addition to the legal one: the trust. Most of those who hold assets in companies established in these territories do so through trusts. Under this system, the beneficiary holds his assets (shares, property, companies, etc.) in a trust which is administered by a trustee. These elements (trust, beneficiary, trustee, shell companies, etc.) are distributed in various Structures linked to different Caribbean jurisdictions. Thus, a trust may be established in one jurisdiction, but its beneficiaries may be in another, the trustee in a third, and the shell companies in a fourth. This is a subject of Structures that is almost impossible for governments to dismantle. This is why when overseas governments agree to share banking information, under pressure from Washington or Brussels, it is of little use because of the secrecy structure itself.

Impact in Latin America

Bank secrecy legislation emerged in Latin America with the goal aim of attracting legally obtained capital. However, during the 1970s and 1980s, this protection on data of current accounts also attracted capital obtained through illicit means, such as drug trafficking and corruption.

During those years, drug lords such as Pablo Escobar used the benefits of the Cayman Islands and other territories to hide their fortunes and properties. On the other hand, several Latin American dictatorships also used these mechanisms to hide the enrichment of their leaders through corruption or even drugs, as was the case with Panama's Manuel Noriega.

Over time, the international community has increased its pressure on tax havens. In recent years the authorities in the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas have made efforts to ensure that their secrecy Structures is not used to launder money for organised crime, but not all territories considered tax havens have done the same.

These opaque networks are used by a considerable part of Latin America's large fortunes. Twenty-seven per cent of Latin America's total private wealth is deposited in countries that offer favourable tax treatment, making it the region with the highest proportion of private capital in these places in the world, according to a 2017 study by the Boston Consulting Group ( agreement ). According to this consultancy firm, this diversion of private wealth is greater in Latin America than in the Middle East and Africa (23%), Eastern Europe (20%), Western Europe (7%), Asia-Pacific (6%) and the United States and Canada (1%).

Tax havens are the destination of a part that is difficult to pinpoint of the total of 335 billion dollars subject to tax evasion or avoidance in the region in 2017, a figure that constituted 6.3% of Latin American GDP (4% lost in personal income tax and 2.3% in VAT), as specified in ECLAC's report Fiscal Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean 2019. This UN economic commission for the region highlights that on average Latin American countries lose more than 50% of their income tax revenues.

The London connection

There have been various theories about the role played by London in relation to tax havens. These theories coincide in presenting a connection of interests between the opaque companies and the City of London, in a network of complicity in which even the Bank of England and the British government could have been involved.

The most important one was expressed by British author Nicholas Shaxson in the book Treasure Island. The thesis was later developed by the documentary film Spiders Web, produced by the Tax Justice Network, whose founder, John Christiansen, worked as advisor for the government of Jersey, which is a special jurisdiction.

The City of London has a separate administration, elected by the still-existing guilds, which represent the City's commercial and banking class . This allows financial operations in this area of the British capital to partially escape the control of the Bank of England and government regulations. A City that is attractive to foreign capital and prosperous is of great benefit to the UK's Economics , as its activity accounts for 2.4% of the country's GDP.

British sovereignty over the overseas territories that serve as tax havens sometimes leads to accusations that the UK is complicit with these financial networks. Downing Street responds that these are territories that operate with a great deal of autonomy, even though London sets the governor, controls foreign policy and has veto power over legislation passed in these places.

Moreover, it is true that the UK government has in the last decade supported greater international coordination to increase scrutiny of tax havens, forcing the authorities there to submit relevant tax information, although the structure of the trusts still works against transparency.

Correct the status

Latin America's problems with tax evasion may be more related to the fragility of its own tax institutions than to the presence of tax havens close to the American continent. At the same time, some tax havens have benefited from political instability and corruption in Latin America.

The effects of domestic capital flight to these places of special tax regimes are clearly negative for the countries of the region, depriving them of increased economic activity and revenue-raising possibilities, and hampering the state's ability to undertake the necessary improvement of public services.

It is therefore imperative that certain corrective policies are put in place. At the national policy level, mechanisms should be put in place to prevent tax evasion and avoidance. At the same time, at the international level, diplomatic initiatives should be shaped to put an end to the Structures of trusts. The OAS offers, in this sense, an important negotiating framework not only with certain overseas territories, but also with its own metropolises, since these, as is the case of the United Kingdom, are permanent observer members of the hemispheric organisation.

The always difficult negotiations are made more difficult by the 75 billion euros the UK is giving up.

ANALYSIS / Pablo Gurbindo Palomo

The negotiations for the European budget for the period 2021-2027 are crucial for the future of the Union. After the failure of the extraordinary summit on 20-21 February, time is running out and the member states must put aside their differences in order to reach an agreement on agreement before 31 December 2020.

framework The negotiation of a new European Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) is always complicated and crucial, as the ambition of the Union depends on the amount of money that member states are willing to contribute. But the negotiation of this new budget line, for the period 2021-2027, has an added complication: it is the first without the United Kingdom after Brexit. This complication does not lie in the absence of the British in the negotiations (for some that is more of a relief) but in the 75 billion euros they have stopped contributing.

What is the MFP?

framework The Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF ) is the EU's long-term budgetary framework deadline and sets the limits for expense of the Union, both as a whole and in its different areas of activity, for a deadline period of no less than 5 years. In addition, the MFF includes a number of provisions and "special instruments" beyond that, so that even in unforeseen circumstances such as crises or emergencies, funds can be used to address the problem. This is why the MFF is crucial, as it sets the political priorities and objectives for the coming years.

This framework is initially proposed by the Commission and, on this basis, the committee (composed of all Member States) negotiates and has to come to a unanimous agreement . After this the proposal is sent to the European Parliament for approval.

The amount that goes to the MFF is calculated from the Gross National Income (GNI) of the Member States, i.e. the sum of the remuneration of the factors of production of all members. But customs duties, agricultural and sugar levies and other revenues such as VAT are also part of it.

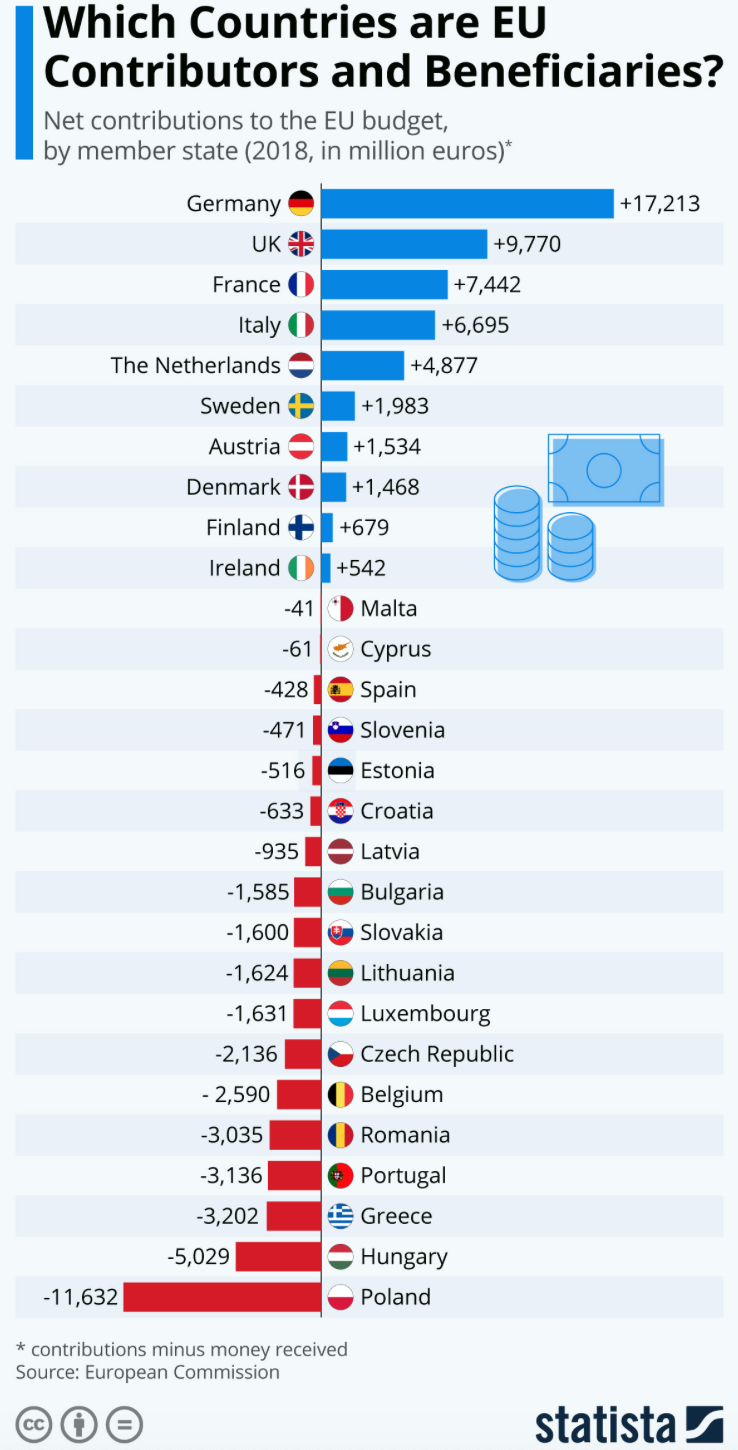

Alliances for war

In the EU there are countries that are "net contributors" and others that are "net receivers". Some pay more to the Union than they receive in return, while others receive more than they contribute. This is why countries' positions are flawed when they face these negotiations: some want to pay less money and others do not want to receive less.

Like any self-respecting European war, alliances and coalitions have been formed beforehand.

The Commission 's proposal for the MFF 2021-2027 on 2 May 2018 already made many European capitals nervous. The proposal was 1.11 % of GNI (already excluding the UK). It envisaged budget increases for border control, defence, migration, internal and external security, cooperation with development and research, among other areas. On the other hand, cuts were foreseen in Cohesion Policy (aid to help the most disadvantaged regions of the Union) and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

The Parliament submitted a report provisional on this proposal in which it called for an increase to 1.3% of GNI (corresponding to a 16.7% increase from the previous proposal ). In addition, MEPs called, among other things, for cohesion and agriculture funding to be maintained as in the previous budget framework .

On 2 February 2019 the Finnish Presidency of committee proposed a negotiation framework starting at 1.07% of GNI.

This succession of events led to the emergence of two antagonistic blocs: the frugal club and the friends of cohesion.

The frugal club consists of four northern European countries: Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Austria. These countries are all net contributors and advocate a budget of no more than 1 % of GNI. On the other hand, they call for cuts to be made in what they consider to be "outdated" areas such as cohesion funds or the CAP, and want to increase the budget in other areas such as research and development, defence and the fight against immigration or climate change.

Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz has already announced that he will veto on committee any proposal that exceeds 1 % of GNI.

The Friends of Cohesion comprise fifteen countries from the south and east of the Union: Spain, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. All these countries are net recipients and demand that CAP and cohesion policy funding be maintained, and that the EU's budget be based on between 1.16 and 1.3 % of GNI.

This large group met on 1 February in the Portuguese town of Beja. There they tried to show an image of unity ahead of the first days of the MFP's discussion , which would take place in Brussels on the 20th and 21st of the same month. They also announced that they would block any subject cuts.

It will be curious to see whether, as the negotiations progress, the blocs will remain strong or whether each country will pull in its own direction.

Outside of these two groups, the two big net contributors stand out, pulling the strings of what happens in the EU: Germany and France.

Germany is closer to the frugals in wanting a more austere budget and more money for more modern items such as digitalisation or the fight against climate change. But first and foremost it wants a quick agreement .

France, for its part, is closer to the friends of cohesion in wanting to maintain a strong CAP, but also wants a stronger expense in defence.

The problem of "rebates

And if all these variables were not enough, we have to add the figure of the compensatory cheques or "rebates. These are discounts to a country's contribution to budget. This figure was created in 1984 for the United Kingdom, during the presidency of the conservative Margaret Thatcher. For the "Iron Lady", the amount that her country contributed to budget was excessive, as most of the amount (70%) went to the CAP and the Cohesion Funds, from which the UK hardly benefited. It was therefore agreed that the UK would have certain discounts on its budgetary contribution on a permanent and full basis.

And if all these variables were not enough, we have to add the figure of the compensatory cheques or "rebates. These are discounts to a country's contribution to budget. This figure was created in 1984 for the United Kingdom, during the presidency of the conservative Margaret Thatcher. For the "Iron Lady", the amount that her country contributed to budget was excessive, as most of the amount (70%) went to the CAP and the Cohesion Funds, from which the UK hardly benefited. It was therefore agreed that the UK would have certain discounts on its budgetary contribution on a permanent and full basis.

These compensatory cheques have since been given to other net contributor countries, but these had to be negotiated with each MFF and were partial on a specific area such as VAT or contributions. An unsuccessful attempt was already made to eliminate this in 2005.

For the frugal and Germany these cheques should be kept, on civil service examination to the friends of cohesion and especially France, who want them to disappear.

Sánchez seeks his first victory in Brussels

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is staking much of his credibility in both Europe and Spain on these negotiations.

In Europe, for many he failed in the negotiations for the new Commission. Sánchez started from a position of strength as the leader of Europe's fourth Economics after the UK's exit. He was also the strongest member of the Socialist group parliamentary , which has been in the doldrums in recent years at the European level, but was the second strongest force in the European Parliament elections. For many, therefore, the election of the Spaniard Josep Borrell as High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, with no other socialist in key positions, was seen as a failure.

Sánchez has the opportunity in the negotiations to show himself as a strong and reliable leader so that the Franco-German axis can count on Spain to carry out the important changes that the Union has to make in the coming years.

On the other hand, in Spain, Sánchez has the countryside up in arms over the prospects of reducing the CAP. And much of his credibility is at stake after his victory in last year's elections and the training of the "progressive coalition" with the support of Podemos and the independentistas. The Spanish government has already taken a stand with farmers, and cannot afford a defeat.

Spanish farmers are highly dependent on the CAP. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food: "in 2017, a total of 775,000 recipients received 6,678 million euros through this channel. In the period 2021-2027 we are gambling more than 44,000 million euros."

There are two different types of CAP support:

-

Direct aids: some are granted per volume of production, per crop (so called "coupled"), and the others, the "decoupled" ones, are granted per hectare, not per production or yield and have been criticised by some sectors.

-

Indirect support: this does not go directly to the farmer, but is used for the development of rural areas.

The amount of aid received varies depending on the sector, but can amount to up to 30 % of a farmer's income. Without this aid, a large part of the Spanish countryside and that of other European countries cannot compete with products coming from outside the Union.

Failure of the first budget summit

On 20 and 21 February an extraordinary summit of the European committee took place in order to reach a agreement. It did not start well with the proposal of the president of the committee, Charles Michel, for a budget based on 1.074% of GNI. This proposal convinced nobody, neither the frugal as excessive, nor the friends of cohesion as insufficient.

Michel's proposal included the added complication of linking the submission of aid to compliance with the rule of law. This measure put the so-called Visegrad group (Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia) on guard, as the rule of law in some of these countries is being called into question from the west of the Union. So, another group is taking centre stage.

The Commission's technical services made several proposals to try to make everyone happy. The final one was 1.069% of GNI. Closer to 1%, and including an increase in rebates for Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Austria and Denmark, to please the frugal and attract the Germans. But also an increase in the CAP to please the friends of cohesion and France, at the cost of reducing other budget items such as funding for research, defence and foreign affairs.

But the blocs did not budge. The frugal ones remain entrenched at 1%, and the friends of cohesion in response have decided to do the same, but at the 1.3% proposed by the European Parliament (even if they know it is unrealistic).

In the absence of agreement Michel dissolved the meeting; it is expected that talks will take place in the coming weeks and another summit will be convened.

Conclusion

The EU has a problem: its ambition is not matched by the commitment of its member states. The Union needs to reinvent itself and be more ambitious, say its members, but when it comes down to it, few are truly willing to contribute and deliver what is needed.

The Von der Leyen Commission arrived with three star plans: the European Green Pact to make Europe the first carbon-neutral continent; digitalisation; and, under Josep Borrell, greater international involvement on the part of the Union. However, as soon as the budget negotiations began and it became clear that this would lead to an increase in the expense, each country pulled in its own direction, and it was these subject proposals that were the first to fall victim to cuts due to the impossibility of reaching an understanding.

A agreement has to be reached by 31 December 2020, if there is to be no money at all: neither for CAP, nor for rebates, nor even for Erasmus.

Member States need to understand that for the EU to be more ambitious they themselves need to be more ambitious and willing to be more involved, with the increase in budget that this entails.

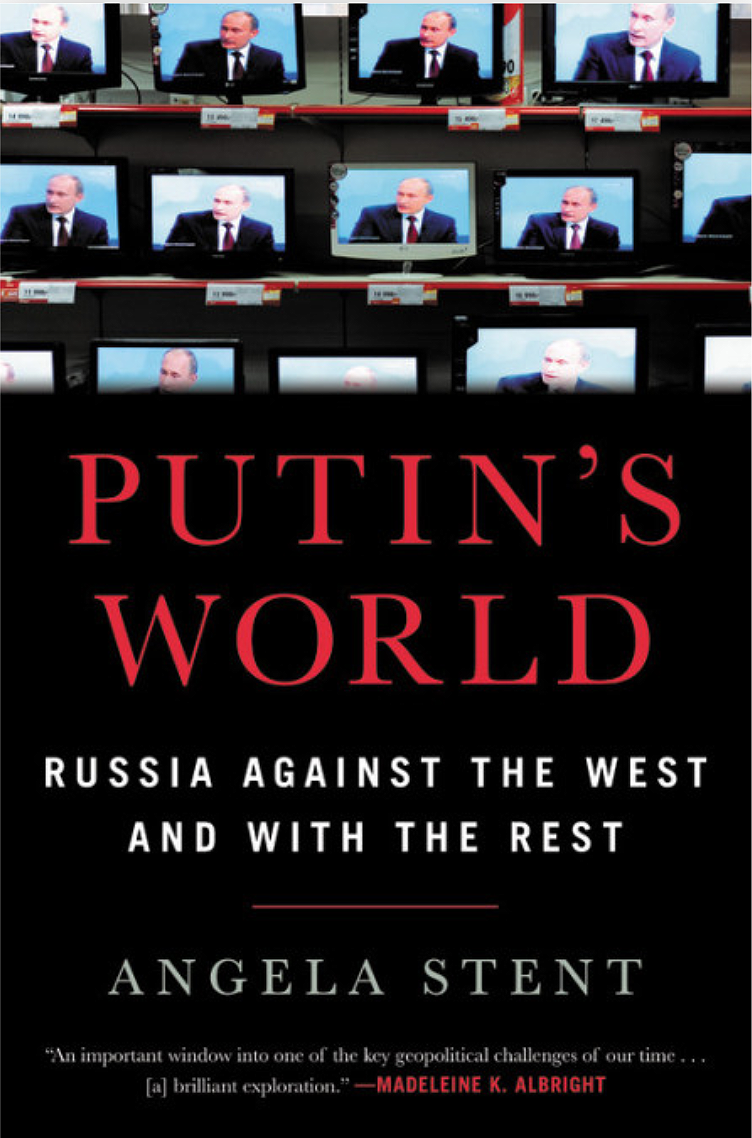

[Angela Stent, Putin's World: Russia Against the West and with the Rest. Twelve. New York, 2019. 433 p.]

review / Ángel Martos

Angela Stent, director of Georgetown University's Center for Eurasia, Russia and Eastern Europe programs of study , presents in this book an in-depth analysis of the nature of Russia at the beginning of the 21st century. In order to understand what is happening today, we sample first look at the historical outlines that shaped the massive heartland that Russian statesmen have consolidated over time.

Angela Stent, director of Georgetown University's Center for Eurasia, Russia and Eastern Europe programs of study , presents in this book an in-depth analysis of the nature of Russia at the beginning of the 21st century. In order to understand what is happening today, we sample first look at the historical outlines that shaped the massive heartland that Russian statesmen have consolidated over time.

Russia took advantage of the global showcase of the 2018 World Cup to present a renewed image. The operation to sell Russia's national brand had some success, as reflected in surveys: many foreign (especially American) spectators who visited the country for the football tournament came away with an improved image of the Russian people, and vice versa. However, what was presented as an opening to the world has not manifested itself in the Kremlin's domestic or international policy: Putin's grip on the hybrid regime that has ruled Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union has not been loosened in the slightest.

Many experts could not predict the fate of this nation in the 1990s. After the collapse of the communist regime, many thought Russia would begin a long and painful road to democracy. The United States would maintain its unique superpower status and shape a New World Order that would embrace Russia as a minor power, equal to other European states. But these considerations did not take into account the will of the Russian people, who understood Gorbachev's and Yeltsin's management as "historical mistakes" that needed to be corrected. And this perspective can be seen in Vladimir Putin's main speeches: a nostalgic feeling for Russia's imperial past, a refusal to be part of a world ruled by the United States, and the need to bend the sovereignty of the once Soviet republics. The latter is a crucial aspect of Russia's foreign policy that, to varying degrees, it has already applied to Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia and others.

What has changed in the Russian soul since the collapse of the Soviet Union? Have relations with Europe suffered ups and downs throughout the history of the Russian Empire? What are these relations like now that Russia is no longer an empire, having lost almost all its power in a matter of years? The author takes us by the hand through these questions. The Russian Federation as we know it today has been ruled by only three autocrats: Boris Yeltsin, Dmitry Medvedev and Vladimir Putin, although one could argue that Medvedev does not even properly count as president, since during his tenure Putin was the intellectual leader behind every step taken in the international arena.

Russia's complicated relations with European countries are notoriously exemplified in the case of Germany, which the book compares to a roller coaster (an expression that is particularly eloquent at Spanish ). Germany is the Federation's door to Europe, a metaphorical door that, throughout contemporary history, has been ajar, wide open or closed, as it is now. After the seizure of Crimea, Merkel's Germany's relations with Moscow have been strictly limited to trade issues. It is worth highlighting the huge differences that can be found between Willy Brandty's Ostpolitik and Angela Merkel's current Frostpolitik. Although Merkel grew up in East Germany, where Putin worked as a KGB agent for five years, and the two can understand each other in both Russian and German, this biographical link has not been reflected in their political relationship.

Germany went from being Russia's biggest European ally (to the extent that Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, after leaving position, was appointed after leaving position chairman of Rosneft's management committee ), to being a threat to Russian interests. After sanctions were imposed on Russia in 2014 with the support of the German government, relations between Putin and Merkel are at their worst. However, some might argue that Germany is acting hypocritically given that it has accepted and financed the Nordstream pipeline, which heavily damages Ukraine's Economics .

Besides the EU, the other main opponent for Russian interests is NATO. At every point on the map where the Kremlin wishes to exert pressure, NATO has strengthened its presence. Under US command, the organisation follows the US strategy of trying to keep Russia at bay. And Moscow perceives NATO and the US as the biggest obstacle to regaining its sphere of influence in "near abroad" (Eastern Europe, Central Asia) and the Middle East.

Putin's fixation with the former Soviet republics has by no means faded over time. If anything, it has increased after the successful annexation of the Crimean peninsula and the civil war that flared up in the Donbass. Russia's nostalgia for what was once part of its territory is nothing more than a pretext to try to neutralise any dissident governments in the region and subjugate as much as possible the countries that make up its buffer zone, for security and financial reasons.

The Middle East also plays an important role in Russian international affairs diary . Russia's main goal is to promote stability and combat terrorist threats that may arise in places that are poorly controlled by the region's governments. Putin has been fighting Islamic terrorism since the separatist threat in Chechnya. However, his possible good intentions in the area are often misinterpreted because of his support in every possible way (including aerial bombardment) for some authoritarian regimes, such as Assad's in Syria. In this particular civil war, Russia is repeating the Cold War proxy war game against the US, which for its part has been supporting the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Kurds. Putin's interest is to keep his ally Assad in power, along with the Islamic Republic of Iran's financial aid .

Angela Stent draws an accurate picture of Russia's recent past and its relationship with the outside world. Without being biased, she succeeds in critically summarising what anyone interested in security should bear in mind when addressing topic Russia's threats and opportunities. For, as Vladimir Putin himself declared in 2018, 'no one has succeeded in stopping Russia'. Not yet.

Criticism of Maduro, the resizing of the Chinese embrace and greater migration control mark the harmony with Washington after ten years of FMLN rule.

The surprising use of the military to pressure the Salvadoran Legislative Assembly in early February to approve a security appropriation has raised international alarm about what the presidency of Nayib Bukele, who came to power in June 2019, may hold. Bukele's first half-year of closer relations with the United States, after two decades of rule by the former FMLN guerrillas, may have led Bukele to believe that his authoritarian gesture would be excused by Washington. The unanimous reaction in the region made him correct the shot, at least for the time being.

![Inauguration of Nayib Bukele as president in June 2019, with his wife, Gabriela Rodríguez [Presidency of El Salvador]. Inauguration of Nayib Bukele as president in June 2019, with his wife, Gabriela Rodríguez [Presidency of El Salvador].](/documents/10174/16849987/bukele-blog.jpg)

▲ Swearing in of Nayib Bukele as president, in June 2019, with his wife, Gabriela Rodríguez [Presidency of El Salvador].

article / Jimena Villacorta

El Salvador and the United States had a close relationship during the long political dominance of the right-wing ARENA party, but the coming to power in 2009 of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) brought El Salvador into alignment with the ALBA countries (mainly Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba), which led to occasional tension with Washington. Furthermore, in 2018, in the final stretch of Salvador Sánchez Cerén's presidency, diplomatic relations with Taiwan were severed and the possibility of strategic investments by China was opened up, which were viewed with suspicion by the United States (especially the option of controlling the Pacific port of La Unión, due to the risk of its military use in a crisis). status .

Nayib Bukele won the early 2019 elections presenting himself as an alternative to the traditional parties, despite the fact that he was mayor of San Salvador (2015-2018) leading a coalition with the FMLN and that for the presidential elections he stayed with the acronym GANA, created a few years earlier as a split from ARENA. His denunciation of the corruption of the political system, in any case, was credible for the majority of an electorate that was certainly tired of the Bolivarian tone of recent governments.

During his electoral campaign, Bukele had already advocated improving relations with the United States, as it is a partner more economically interesting for El Salvador than the ALBA nations. "Any financial aid that comes is welcome, and better if it is from the United States", said one of his advisors. These messages were immediately received in Washington, and in July the US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, visited El Salvador: it was the first time in ten years, precisely the time of the FMLN's two consecutive presidencies, that the head of US diplomacy had visited the Central American country. This trip served to accentuate the partnership at subject in the fight against drug trafficking and the gang problem, two shared problems. "We have to fight the MS-13 gang, which has sown destruction in El Salvador and also in the United States, because we have its presence in almost 40 of the 50 states in our country," Pompeo said.

In line with the change of orientation it was undergoing, El Salvador began to align itself in regional forums against the regime of Nicolás Maduro. Thus, on 12 September, the Salvadoran representation in the Organisation of American States (OAS) supported the activation of the Inter-American Reciprocal Treaty of attendance (TIAR), after years of abstaining or voting in favour of resolutions supporting Chávez's Venezuela. On 3 December Bukele announced the expulsion from El Salvador of Maduro's government diplomats, an action immediately replicated by Caracas.

In the same months, El Salvador accepted the terms of the new migration approach that the Trump administration was outlining. During the summer, the White House negotiated with the countries of the Central American Northern Triangle agreements similar to the safe third country mechanism, whereby Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador agreed to process as asylum seekers those who had passed through their territory and ended up in the US by formalising this application. Bukele met with Trump in September at the United Nations General Assembly framework and signed the agreement, which was presented as an instrument to combat organised crime, strengthen border security, reduce smuggling and human trafficking.

The signature of agreement proved to be controversial, as many authorities questioned the guarantees of security and protection of rights that El Salvador can offer, when it is the lack of such guarantees that is driving the emigration of Salvadorans. Rubén Zamora, El Salvador's former ambassador to the UN, criticised the fact that Bukele was conceding a great deal to the United States, with hardly anything in return.

Bukele, however, was able to showcase a US counterpart in October: the extension for one year, until January 2021, of the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) that provides legal cover for the presence of 250,000 Salvadorans and their families in the US. The total number of Salvadorans residing in the US is at least 1.4 million, the largest number of Latin American migrants after Mexicans. This sample shows the strong link between the Central American nation, home to 6.5 million people, and the great power of the North, which is also the destination of 80% of its exports and whose dollar is the currency used in El Salvador.

The new Salvadoran president appeared to cut short this harmony with Washington in December, when he made an official trip to Beijing and met with the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping. The US had warned of the risk of China taking strategic advantage of the door that was opening in Central America with the successive establishment of diplomatic relations with the countries of the American isthmus, which until a few years ago were a stronghold of support for Taiwan. In particular, the US embassy in El Salvador had been particularly active in denouncing the Sánchez Cerén government's alleged efforts to grant China the management of the Port of La Unión, in the Gulf of Fonseca, which could be joined by a special economic zone.

However, what Bukele did on this trip was to resize, at least for the time being, this relationship with China, limiting expectations and calming US suspicions. Not only does the question of the port of La Unión seem to have been shelved, but the Salvadoran president also confined China's attendance to the realm of financial aid at development and not to the granting of credits which, in the event of non-payment, condition national sovereignty. Bukele specified that the "gigantic cooperation" promised by China was "non-refundable" and referred to typical international cooperation projects, such as the construction of a Library Services, a sports stadium and a sewage treatment plant to clean the sewage discharged into Lake Ilopango, near the capital.

![People in a rural area of Cameroon [Photokadaffi]. People in a rural area of Cameroon [Photokadaffi].](/documents/10174/16849987/cameroon-blog.jpg)

▲ People in a rural area of Cameroon [Photokadaffi].

ESSAY / EMILIJA ŽEBRAUSKAITĖ

Introduction

In seeking to better understand the grounds of Islamic fundamentalism in Africa, it is worth to looks for the common denominators that make different areas prone to the insurgence of extremism. In the continent of boundaries that were mainly drawn by the Europeans, many countries contain a multitude of cultures and religions, all of them in constant interaction and more often than not - friction with each other. However, in order to classify the region as highly susceptible to the inter-religious or inter-cultural conflict to happen, there are more important factors that must be taken into consideration. Through quantitative study and document analysis, this article, with an example of the rise of Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria and the expansion of the group to the neighbouring countries such as Cameroon, will underline the most important problems that paved the path for the emergence and spread of the Islamic fundamentalism, discussing its historical, social and ideological origins, at the same time providing possible long-time solutions on social and ideological ground.

The brief history of Islam in Nigeria and Cameroon

The arrival of Islam to Nigeria dates back to the 11th and 12th centuries, when it spread from North Africa through trade and migration. It incorporated Husa and Fulani tribes into the common cultural ground of Islam which extended throughout North Africa, introducing them to the rich Islamic culture, art, Arabic language and teachings. In the 19th century, Fulani scholar named Usman Dan Fodio launched a jihad, establishing a Sokoto Caliphate ruled under a strict form of Shari'a law, further spreading Islamic influence in the region, introducing it for the first time to the area which today forms the Northern part of Cameroon, another country of our analysis.

The Sokoto Caliphate remained the most powerful state in Western Africa until the arrival of the European colonists. As opposed to the Southern part of Nigeria which was colonized and Christianized, the North received a lesser portion of Western education and values, as the Europeans ruled it indirectly through the local leaders. The same happened with Cameroon, which was indirectly ruled by the Germans in the North and experienced a more direct Westernization in the South. Even the indirect rule, however, brought great changes to the political and judicial processes, which became foreign to the local inhabitants. "This was viewed by Muslim northerners as an elevation of Christian jurisprudence over its Islamic judicial heritage" (Thomson, 2012) and the experience was without a doubt a humiliating and painful one - a foreign body destroying the familiar patterns of a lifestyle led for centuries, implementing a puppet government, diminishing the significance of a Sultan to that of a figurehead.

After their corresponding independence in 1960, both Nigeria and Cameroon became what American political scientist Samuel Huntington called cleft countries - composed of many ethnical groups and two major religions - Christianity in the South and Islam in the North. This situation, as described by Huntington, can be called the clash of civilizations between Islamic and Western tradition. He identifies the similarity between the two religions as one of the main reasons for their incompatibility: "Both are monotheistic religions, which, unlike the polytheistic ones, cannot easily assimilate additional deities, and which see the world in dualistic, us-and-them terms" (Huntington, 2002).

The independence also brought secularization of the two countries, thus undermining in both the political Islamism and the idea that Muslims should be ruled by the law of God, and not the law of men. However, the long-lasting Islamic tradition uniting the Northern Nigeria (and to some extent Northern Cameroon, although it was introduced to Islam much later) with the rest of North Africa and separating it from its Southern counterpart prevailed: "The Sokoto Caliphate remains a not-so-very distant and important reference point for Nigeria's Muslims and represents the powerful role that jihad and Shari'a law played in uniting the region, rejecting corruption, and creating prosperity under Islam" (Thomson, 2012).

Fertile ground for fundamentalism

Out of the romantic sentiments of long lost glory, it is not too difficult to incite resentment for modernity. To a certain extent, a distaste for the Westernization, which was an inevitable part of modernizing a country, is justifiable. After all, European imperialism selfishly destroyed indigenous ways of life enforcing their own beliefs and political systems, ethics, and norms a practice that continued even after decolonisation. Yet, the impetus for the growth of Islamic fundamentalism in Nigeria as well as other places in Africa can be found as much in the current situation as in the past grievances.

In Nigeria specifically, the gap was further enhanced by different European policies concerning the Northern and Southern parts of the country. Along with the more direct Westernisation, the Southern part of Nigeria was also better educated, familiar to Western medicine, bureaucracy, and science. It had an easier time to adapt to forming part of a modern liberal state. According to the data published in Educeleb, by 2017 Nigeria's literacy rate was 65.1% (Amoo, 2018). All the Southern states were above the national average and all the Northern ones were below. The same statistics also depict the fact that the difference between literacy level between genders is barely noticeable in the Southern states, while in the Northern states the gap is much wider.

Apart from the differences mentioned above, the Southern region is the place where the oil-rich Niger delta, which in 2018 contributed to 87.7% of Nigeria's foreign exchange, is situated (Okpi, 2018). It can be argued that the wealth is not equally distributed throughout the country and while the Christian South experiences economic growth, it often does not reach the Northern regions with Muslim majority. "Low income means poverty, and low growth means hopelessness", wrote Paul Collier in his book The Bottom Billion: "Young men, who are the recruits for rebel armies, come pretty cheap in an environment of hopeless poverty. Life itself is cheap, and joining a rebel movement gives these young men a small change of riches" (Collier, 2007).

The rise of Boko Haram

In this disproportionally impoverished Northern part of the country and with the goal of Islamic purification for Northern Nigeria, a spiritual leader, Muhammad Yusuf, founded an organisation which he called People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet's Teachings and Jihad. The locals, however, named it Boko Haram, which literally means books are forbidden and reflects the organisation's rejection of Western education and values. Boko Haram was founded in 2002 in Borno state, Maiduguri, where Yusuf established a mosque and Koranic school in which he preached Islamic teachings with a goal of establishing an Islamic state ruled by Shari'a law. "Western-style education is mixed with issues that run contrary to our beliefs in Islam" (Yusuf, 2009).

Although the organisation seemed to be peaceful enough for Nigerian government to ignore it for the first seven years of its existence, from the start Boko Haram was antagonistic towards the secular government which they associated with corruption, Christian-domination and Western influence. In 2009 the confrontation between the group and Nigeria's security forces led to and extrajudicial killing of the Muhammed Yusuf in captivity (Smith, 2009). The event became an impetus for the pre-existing animosity Boko Haram felt for the state to grow into an actual excuse for violence. Since 2009 the group was led by Abubakar Shekau who replaced Muhammad Yusuf after his death.

The attacks of the organisation became more frequent and brutal, killing many civilians in Nigeria and neighbouring countries, Muslims and Christians alike. Although its primary focus laid on the state of Borno, after being pushed out of its capital Maiduguri, Boko Haram became a rural-based organisation, operating in the impoverished region around Lake Chad basin (Comolli, 2017). Apart from Nigeria, the countries in which Boko Haram inflicted damage include Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad and Cameroon, the latest being the subject of analysis in this essay.

Impact of Boko Haram in Nigeria and Cameroon

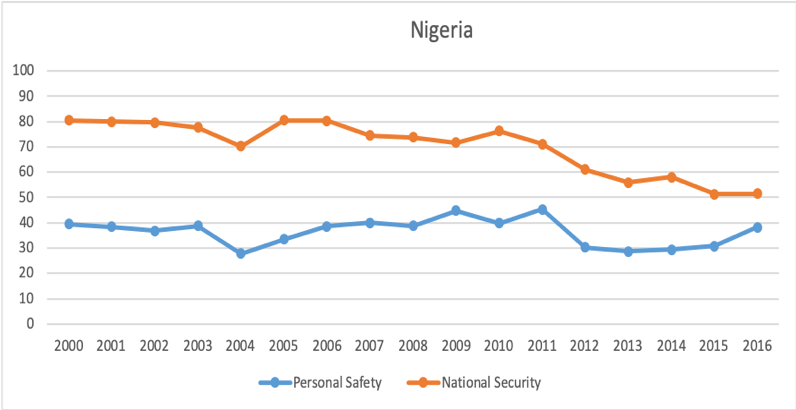

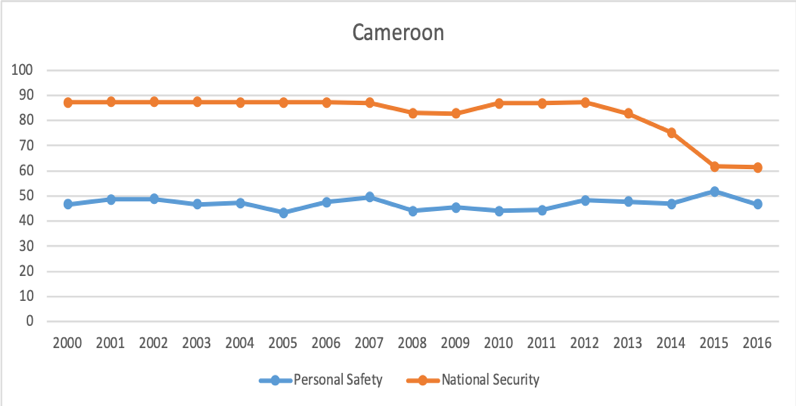

To illustrate the impact the terrorist group had on the partner-economic development of the region, we will look at the Mo Ibrahim Index of African Governance (Ibrahim Index of African Governance, n.d.). As an example, we will evaluate the perception of staff security and level of national security in Nigeria - a country in which the Boko Haram had originated, and Cameroon - one of the countries where it spread after Nigeria's government launched their counter-terrorism program. The timeline for the graphs runs from the year 2000 to 2016 in order to capture the changes in national security and staff safety in Cameroon and Nigeria. This aid the study in drawing concrete conclusions over a period of time.

Figure 1: Impact of Boko Haram on staff Safety and National Security in Nigeria.

Source: Mo Ibrahim Index

The perception of staff safety in Nigeria, according to Mo Ibrahim Index of African Governance, started decreasing since 2010. The tendency can be explained by the fact that in 2009 Nigerian government confronted the fundamentalist group, after which it became more active and violent. The perception of staff safety also dropped after 2014, the year that was marked by the infamous capturing of 276 Chibok schoolgirls out of their school dormitory. When it comes to the index portraying the level of national security, similar tendencies can be seen characterized by the drop of national security in 2009 and after 2014.

Figure 2: Impact of Boko Haram on staff Safety and National Security in Cameroon

Source: Mo Ibrahim Index

Another example can be Cameroon, the second most affected country after Nigeria which was infiltrated by Boko Haram in 2009. During that time, however, the presence of the terrorist group in the North of Cameroon was rather unassertive. At first the group was focusing on establishing their connections, gaining Cameroonian recruits, using the country as a transit of weapons to Nigeria (Heungoup, 2016). With the beginning of the kidnapping of foreigners, however, the year 2013 is marked by the drop of national security in the country. By 2014, the Cameroonian government declared war against Boko Haram, to which the group responded with a further increase of violence and thus - further drop of national safety.

An additional peak of terrorist attacks can be noticed after the renewed wave of governmental resistance after the 2015 elections in Nigeria which strongly weakened Boko Haram's influence, at the same time leading to increasingly asymmetric warfare. In Cameroon alone, Boko Haram executed more than 50 suicide bombers attacks, which killed more than 230 people (Heungoup, 2016). In the end, it is clear that despite the efforts of Nigerian and Cameroonian governments in fighting Boko Haram by declaring the war against terrorism, it cannot be said with certainty that the response of the governments of these countries were effective in eliminating or even containing the terrorist group. On the contrary, it seems that pure military resistance only further provoked the terrorist group and led to an increase of violence.

Response of the government

The outbreak of violence at the instigation of Boko Haram elicited a similar response from Nigerian armed forces in 2009 (Solomon, 2012). The office of president Goodluck Johnson launched a military mission in Maiduguri, which united the Nigerian Police Force with the Department of State Security, the army, the navy and the air force (Amnesty, 2011). Extra attention was bestowed upon the emergency regions of Borno, Niger, Plateau and Yobo (Economist, 2011).

In order to prevent Boko Haram from hiding and regrouping in the neighbouring states after being actively fought in Nigeria, the government tightened the border security in the North, however, as it has already been explained, the tactics failed miserably as Boko Haram was able to hide and regroup in Nigeria's Northern neighbours after being pushed out of Nigeria. The effort to prevent Boko Haram from gaining foreign support, financing and reinforcement were also dysfunctional, as the terrorist group was successful in finding allies. With the support of other Islamist groups such as Al Qaeda, the previously local problem is becoming more globalized and requires equally global and coordinated efforts to fight it.

And yet, so far the policy of Goodluck Johnson was proven counterproductive due to the internal problems of Nigerian security process such as corruption, unjustified violence, extrajudicial killings as opposed to intelligence-based operations (Amnesty, 2011, p. 30). Another problem can be identified in the specific case of Nigeria being a melting pot of cultures and religions. Each region requires a unique approach based on the understanding of the culture, values and customs of the area. Yet, the Nigerian soldiers in charge of the safety of the Northern states were National instead of local, making the indigenous population feel controlled by the foreign body.

So far, the policy of president Muhammadu Buhari, who was elected in 2015, was not much more successful than his predecessor's. At the beginning of his presidency, Buhari was successful in reclaiming the territory occupied by Boko Haram and was quick to announce the defeat of the terrorist group. However, after losing their ground in Nigeria, Boko Haram again retreated to regroup in the neighbouring countries, only to re-emerge again multiplied into two distinct terrorist organisation, further complicating the resistance. Overall, the use of force has proven to be ineffective in striking down terrorism. The previous examples lead to the conclusion that the use of dialogue and changes in national policies, as opposed to pure force, are crucial for the long term solutions.

Solution to Boko Haram

According to United Nations development program report "Journey to Extremism in Africa: Drivers, Incentives and the Tipping Point for Recruitment" the main factors that make a person prone to get involved with fundamentalism are childhood circumstances, lack of state involvement in their surroundings, religious ideologies, and economic factors (UNDP, 2017). In order to prevent violent extremism, it must be tackled at the roots, because, as we have already seen before, facing violence with further violence approach provided little improvement on the status quo.

Childhood experience may be one of the fundamental reasons for joining extremism later. Members of marginalized communities, in which children were facing staff problems such as lack of parental involvement, lack of education, lack of exposure to different ethnicities and religions, are especially vulnerable. In these borderland areas, the children are rarely entitled to social security, they are often distrustful of the government and do not develop any sense of national belonging. The trust that the government favours some over others is only strengthened by staff witnessing of bribe-paying and corruption. The staggering 78% of the responders of the UN research reported being highly mistrustful of the police, politicians and the military (UNDP, 2017).

The isolation and minimum exposure to other ethnic and religious groups also contribute to the feeling of segregation and suspicion towards others. 51% of recruits have reported having joined due to religious beliefs, some in fear of their religion being endangered. However, even a higher percentage of 57 confessed their understanding of the sacred texts to be limited. This closes the circle of poverty and lack of education, with unemployment being the priority factor for 13% of the volunteer recruits questioned. In the end, are there any possible solutions for this continuous lemniscate (UNDP, 2017)? If there are any they must be in line with the theory of security-development nexus. By increasing the quality of the former, the later will be activated into motion and vice versa. Eliminate one of them and the other will stabilize itself naturally.

The few solutions tackling both lack of security and slow development can be named, starting with combating the traumatizing childhood experiences. Long term solutions are undoubtedly based on the provision of education and social security which would aim to ensure the school attendance, community support for the parents and child-welfare services. The civil education is no less important to encourage the sense of national belonging and trust in the government, which also includes harsher anti-corruption regulations and more government spending directed to the marginalized communities. Strategies to promote a better understanding of the religion as a counterforce for the ignorance leading to easy recruitment, encouraging religious leaders to develop their own anti-extremism strategy, are also solutions that address the often expressed fears of religious groups who feel excluded, their faith being depreciated. The last but not least are the provision of work opportunities in the risk areas - promoting entrepreneurship, facilitating the access of the markets, upgrading infrastructure, basically creating economic opportunities of dignified employment and livelihood.

Ideological background-check