Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label framework multi-year financial .

Faced with the biggest economic crisis since World War II, the EU itself has decided to borrow to help its member states.

▲ Commission President Von der Layen and the President of the European committee Charles Michel after announcing the agreement in July [committee European]

ANALYSIS / Pablo Gurbindo Palomo

"Deal!". With this "tweet" at 5:30 a.m. on 21 July last, the president of the European committee , Charles Michel, announced the achievement of a agreement after the longest meeting in its history (more than 90 hours of negotiations).

framework After the failed summit in February, European countries were aware of the importance of reaching an agreement on agreement, but some countries saw it as more urgent than others to conclude the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for the next seven years. But as with everything else, the Covid-19 pandemic has overturned this lack of urgency, and has even forced member states to negotiate, in addition to the budget, aid to alleviate the effects of the pandemic on the 27.

The agreement consists of an MFF of 1.074 trillion euros. This is lower than the figure demanded in February by the so-called friends of cohesion (a conglomerate of southern and eastern European countries) and the Commission itself, but also higher than the figure that the frugals (the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Sweden) were prepared to accept. But it is not this figure that has been the focus of the discussion, but how much and how the post-pandemic recovery fund to help the countries most affected by the pandemic was to be set up. The Fund was agreed at 750 billion, divided into 390 billion to be given to member states in the form of grants, and the remaining 360 billion to be given in the form of a 70 per cent disbursable loan between 2021 and 2022.

The figures are staggering, and based on the February negotiations, where one part of the membership preferred something more austere, one might ask: How did we arrive at this agreement?

The Hamilton moment

With the arrival of Covid-19 in Europe and a considerable paralysis of all the world's economies, the European capitals quickly realised that the blow was going to be significant and that a strong response was going to be necessary to mitigate the blow. Proposals at the European level were not long in coming. For example, the European Parliament proposed a recovery package on 15 May of 2 trillion euros, and to include this in the MFF 2021-2027.

The most prominentproposal was presented on 18 May by French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel. And not only because it was promoted by the two main economies of the Union, but also because of its historic content.

There has been talk of Hamilton momentHamilton moment, referring to Alexander Hamilton, one of the founding fathers of the United States and the first Secretary of the Treasury of the newly founded republic. In 1790 the thirteen states that made up the young American nation were heavily indebted due to the war effort of the Revolutionary War, which had ended only seven years earlier. To solve this problem, Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury, succeeded in convincing the federal government to assume the states' debt by "mutualising" it. This event marked the strengthening of the American federal government and served to create the instructions of the US national identity.

It seems that with the Franco-German proposal the Hamilton moment has arrived. The proposal is based on four pillars:

-

European health strategy, which could include a joint reservation of medical equipment and supplies, coordination in the purchase of vaccines and treatments. In turn, epidemic prevention plans shared among the 27 and common methods for registering the sick.

-

A boost to the modernisation of European industry, supported by an acceleration of the green and digital transition.

-

Strengthening the European industrial sector, supporting production on the Old Continent and the diversification of supply chains to reduce global dependence on the European Economics .

-

500 billion reconstruction fund for the regions most affected by the pandemic on the basis of EU budget programmes.

It is this fourth pillar that we can call "Hamiltonian" and which is historic as it would for the first time in history allow the EU itself to issue debt to finance this fund. This proposal has broken years of a German stance against any collective borrowing subject . "We are experiencing the biggest crisis in our history... Because of the unusual nature of the crisis we are choosing unusual solutions," Merkel said in the joint video conference with Macron.

According to this proposal the funds would not be reimbursed directly by the countries but through the Community funds in the long term deadline, either through its usual resources or through new sources of income. It should also be noted that the proposal spoke of the submission of this fund in the form of subsidies, i.e. without any subject interest for the recipient countries.

Among the reactions to proposal were those of the frugal, who rejected that the funds should be given in the form of grants. "We will continue to show solidarity and support for the countries most affected by the coronavirus crisis, but this must be in the form of loans and not subsidies," said Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz. The frugal proposal is that the financial aid raised on the debt markets should be submit to states at low interest rates, i.e. as a loan, and conditional on a reform programme.

On 27 May the Commission announced its proposalThe EU's new, very similar to the Franco-German one, but enlarged. The proposal is composed of a 1.1 trillion euro MFF and a 750 billion euro recovery plan called Next Generation EU. This recovery plan is based on three pillars financed by new instruments but within pre-existing headings:

The first pillar covers 80% of the recovery plan. It is about supporting Member States in their investments and reforms in line with the Commission's recommendations. To this end, the pillar has these instruments:

-

Recovery and Resilience Mechanism (the most important part of proposal): financial support for investments and reforms by states, especially those related to the green and digital transition and the resilience of national economies, linking them to EU priorities. This mechanism would be made up of 310 billion in grants and 250 billion in loans.

-

React-EU Fund under cohesion policy with 55 billion.

-

Increase in the Just Transition Fund: this fund is intended to support states in undertaking the energy and ecological transition, to move towards a climate-neutral policy. It would be increased to 40 billion.

-

Increase of the European Agricultural Fund development Rural: to support rural areas to comply with the European Green agreement . It would be increased by 15 billion.

The second pillar covers 15% of the plan. It focuses on boosting private investment, and its funds would be managed by the European Investment Bank (EIB):

-

31 billion Solvency Support Instrument

-

EU-Invest programme increased to $15.3 billion

-

New Strategic Investment Fund to promote investment in European strategic sectors

The third pillar covers the remaining 5%. It includes investments in areas that have result been key to the coronavirus crisis:

-

EU4Health programme to strengthen health cooperation. With an budget of 9.4 billion.

-

Reinforcement of the EU Civil Protection Mechanism (EUCPF) by 2 billion.

-

project Horizon Europe for the promotion of research and innovation worth 94.4 billion.

-

Support to the external humanitarian financial aid worth 16.5 billion.

To raise the funding, the Commission would issue its own debt on the market and introduce new taxes of its own, such as a border carbon tax, emission allowances, a digital tax or a tax on large corporations.

It should also be noted that both access to MFF and Next Generation EU aid would be conditional on compliance with the rule of law. This was not to the liking of countries such as Hungary and Poland, which, among others, consider it to be unclear and a form of interference by the EU in their internal affairs.

Negotiation at the European Summit

With this proposal on the table, the heads of state and government of the 27 met on 17 July in Brussels amid great uncertainty. They did not know how long the summit would last and were pessimistic that it would be possible to reach an agreement agreement.

The main sticking points in the negotiations were the amount and form of the reconstruction fund. Countries such as Spain, Italy and Portugal wanted the aid to come in the form of subsidies in full and without any subject conditionality. On the other hand, the frugals, led during the summit by Mark Rutte of the Netherlands, wanted the reconstruction fund to be reduced as much as possible, and in any case to be given in the form of loans to refund and as an "absolute precondition". "Any financial aid from the North means reforms in the South. There is no other option", Rutte said at a press conference in The Hague.

As with all negotiations, the positions were gradually loosening. It was already clear that neither position was going to remain unscathed and that a mixed solution with both subsidies and loans was going to be the solution. But in what percentage? And with reform conditionality?

For Spain, Italy and Portugal the subsidies could not be less than 400 billion, which was already a concession from the initial 500 billion. For the frugal, who were joined by Finland, this figure could not exceed 350 billion, which would reduce the total Fund to 700 billion. This was a major concession by the frugals, who went from talking about zero subsidies to accepting them as 50% of the amount. Michel's final proposal was 390 billion in subsidies and 360 billion in loans to try to convince all sides.

The big stumbling block apart from the percentage was the conditionality of reforms for the submission aid that the frugal advocated. The spectre of the Troika imposed after the 2008 crisis was beginning to appear, to the disgrace of countries such as Spain and Italy. Rutte demanded that the national plans that countries had to present to the Commission in order to receive the Fund should also pass through committee of the 27 and that unanimous approval was necessary. This formula basically allowed any country to veto the national plans. Germany did not go as far as the required unanimity, but did ask for some control by the committee.

Rutte's stance angered many countries that saw proposal as a way of forcing reforms that have nothing to do with economic recovery.

The president of the committee presented a proposal to bring the parties closer together: the "emergency brake". According to Michel's proposal countries will have to send their reform plan to committee and it will have to be C by qualified majority. deadline After its approval, any country is allowed to submit its doubts about the fulfilment of the plans presented by a state to the committee ; in this case, the committee would have a maximum of three months to make a pronouncement. As long as the country does not receive a decision, it would not receive the aid.

For those who may be surprised by the large concessions made by the frugal, it is worth mentioning the figure of the "rebates" or compensatory cheques. These are rebates on a country's contribution to budget and were introduced in 1984 for the United Kingdom. The British were one of the main net contributors to the European budget , but they hardly benefited from its aid, 70% of which went to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the Cohesion Fund. It was therefore agreed that the British would have their contribution discounted on a permanent basis. Since then, other net contributor countries have been receiving these cheques. However, in these cases they had to be negotiated with each MFF and were partial on a specific area.

It is a very controversial figure for many countries, and an attempt was already made to remove it in 2005. But what is undeniable is that it is a great bargaining chip. From the outset, the frugal countries have wanted to keep it, and even strengthen it. And given the difficulties in negotiating, the rest of the member states have seen that it is an "affordable" and not very far-fetched way of convincing the "hawks of the north". After some initial posturing, they ended up increasing it: Denmark will receive 377 million (considerably more than the initial 222 million); Austria will double its initial amount to 565 million; Sweden will receive 1.069 billion (up from the initial 823 million); and the Netherlands will receive 1.575 billion. Notably, Germany, as the largest net contributor, will receive 3.671 billion.

The last important negotiation point to be addressed is the conditionality of compliance with the rule of law in order to receive the different funds and aid. Hungary and Poland, for example, have an open transcript for possible violation of article 7 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), which allows a member state to be sanctioned for violating basic EU values such as respect for human rights or the rule of law. Many countries have pressed the issue, but in the face of difficult negotiations and a possible risk of a veto of agreement depending on the vocabulary used by Hungarian President Viktor Orban, this clause has come to nothing.

To recapitulate, and as stated at the beginning of article, the agreement ended up with an MFF of 1.074 trillion euros; and a post-pandemic reconstruction fund, the Next Generation EU, of 750 billion, divided into 390 billion in the form of subsidies and 360 billion in the form of loans. To this must be added Michel's "emergency brake" for the submission of aid and the significant sum of "rebates".

The cuts

Yes, there have been. Apart from the aforementioned rule of law clause, there have been several cuts in several of the items proposed by the Commission. Firstly, there has been a significant cut in the Just Transition Fund, which has been reduced from the initial 40 billion at proposal to 10 billion, to the anger of Poland in particular. Secondly, the funds for the rural development are reduced from 15 billion to 7 billion. Thirdly, both the 16.5 billion external humanitarian support fund financial aid , the 31 billion solvency support instrument (on its proposal by the Commission) and the 9.4 billion EU4Health programme have come to nothing. And finally, the project Horizon Europe would drop from the 94.4 billion proposed by the Commission to a mere 5 billion.

Winners and losers?

It is difficult to speak of winners and losers in a negotiation where all parties have given quite a lot in order to achieve agreement. Although it remains to be seen whether the countries' positions were truly immovable from the outset or whether they were simply used as an instrument of pressure in the negotiation.

The countries most affected by the pandemic, such as Italy and Spain, can be happy because they will receive a very large sum in the form of subsidies, as they wanted. But this conditionality that they were not going to accept in any way, in a way, is going to come to them softened in the form of Michel's "emergency brake". And the reforms they did not want to be forced to make, they will have to carry out from agreement with the recovery plan they send to committee, which if they are not sufficient may be rejected by the latter.

The frugal have succeeded in getting conditional aid, but more than half of it will be in the form of subsidies. And as a rule, the monetary limits they advocated have been exceeded.

Countries such as Poland or Hungary have succeeded in making the conditionality of the rule of law ineffective in the end, but on the other hand they have received considerable cuts in funds, such as the Just Transition fund, which are important especially in Central Europe for the energy transition.

But, on final, every head of state and government has returned home claiming victory and assuring that he or she has fulfilled his or her goal, which is what a politician must do (or appear to do) at the end of the day.

For both the MFF 2021-2027 and Next Generation EU to go ahead, the European Parliament still needs to ratify it. Although the Parliament has always advocated a more ambitious package than agreed, there is no fear that it will block it.

Conclusion

As I have said, this agreement can be described as historic for several reasons. Apart from the obvious extension of the European committee or the Covid-19 pandemic itself, it is historic because of the Hamilton moment that seems to be about to take place.

Member states seem to have learned that the post-crisis formula of 2008 did not work, that crises affect the whole of the Union and that no one can be left behind. Cases such as Brexit and the rise of Eurosceptic movements across the continent set a dangerous precedent and could even endanger the continuity of project.

The "mutualisation" of debt will allow states that are already heavily indebted, and which due to their high risk premium would have problems financing themselves, to get out of the crisis sooner and better. This decision will obviously cause problems that remain to be seen, but it shows that the 27 have realised that a joint financial aid was necessary and that they cannot go to war on their own. As Merkel said when presenting her post-pandemic plan together with Macron: "This is the worst crisis in European history", adding that to emerge "stronger", it is necessary to cooperate.

This move towards a certain fiscal unity can be seen as a rapprochement to a Federal Europe, at least in the Eurozone, which has been discussed for decades now. Whether this is a path with or without return remains to be seen.

The always difficult negotiations are made more difficult by the 75 billion euros the UK is giving up.

ANALYSIS / Pablo Gurbindo Palomo

The negotiations for the European budget for the period 2021-2027 are crucial for the future of the Union. After the failure of the extraordinary summit on 20-21 February, time is running out and the member states must put aside their differences in order to reach an agreement on agreement before 31 December 2020.

framework The negotiation of a new European Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) is always complicated and crucial, as the ambition of the Union depends on the amount of money that member states are willing to contribute. But the negotiation of this new budget line, for the period 2021-2027, has an added complication: it is the first without the United Kingdom after Brexit. This complication does not lie in the absence of the British in the negotiations (for some that is more of a relief) but in the 75 billion euros they have stopped contributing.

What is the MFP?

framework The Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF ) is the EU's long-term budgetary framework deadline and sets the limits for expense of the Union, both as a whole and in its different areas of activity, for a deadline period of no less than 5 years. In addition, the MFF includes a number of provisions and "special instruments" beyond that, so that even in unforeseen circumstances such as crises or emergencies, funds can be used to address the problem. This is why the MFF is crucial, as it sets the political priorities and objectives for the coming years.

This framework is initially proposed by the Commission and, on this basis, the committee (composed of all Member States) negotiates and has to come to a unanimous agreement . After this the proposal is sent to the European Parliament for approval.

The amount that goes to the MFF is calculated from the Gross National Income (GNI) of the Member States, i.e. the sum of the remuneration of the factors of production of all members. But customs duties, agricultural and sugar levies and other revenues such as VAT are also part of it.

Alliances for war

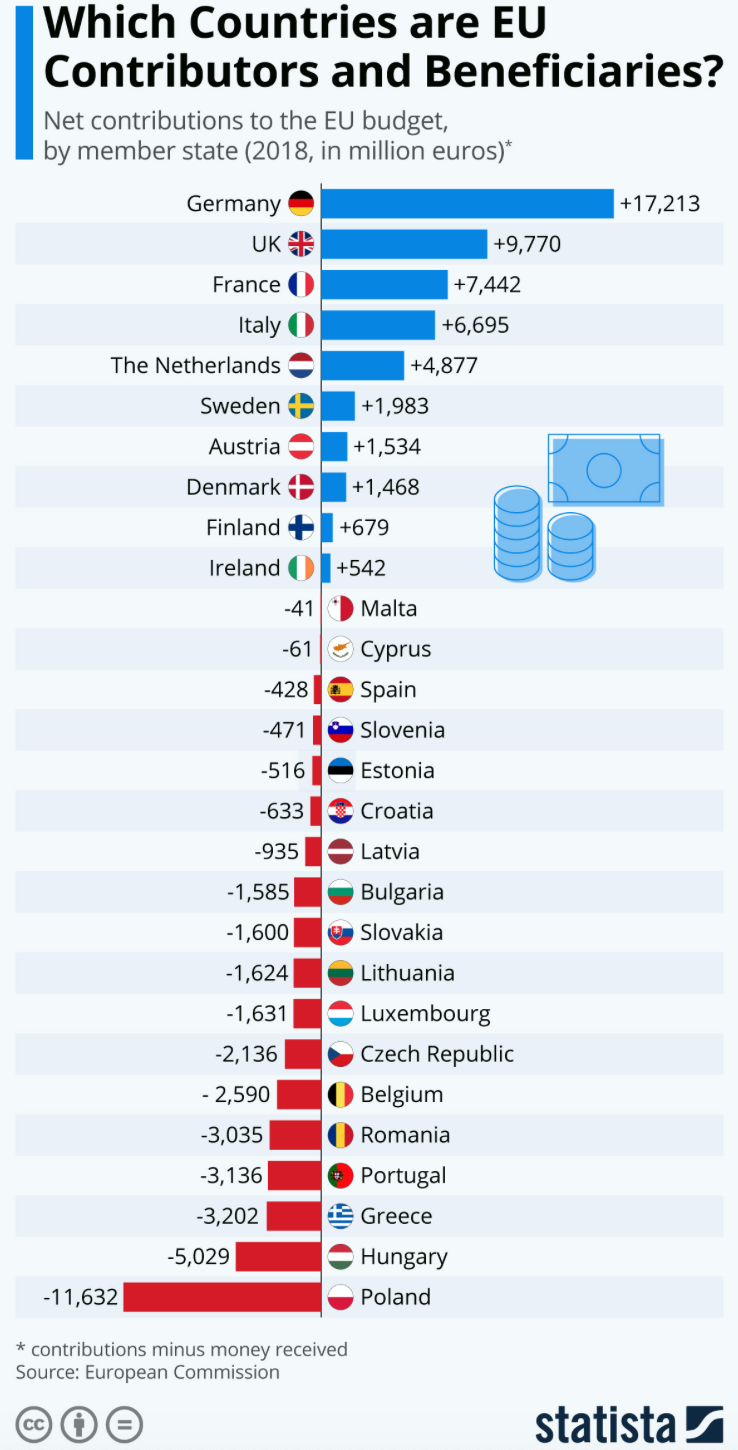

In the EU there are countries that are "net contributors" and others that are "net receivers". Some pay more to the Union than they receive in return, while others receive more than they contribute. This is why countries' positions are flawed when they face these negotiations: some want to pay less money and others do not want to receive less.

Like any self-respecting European war, alliances and coalitions have been formed beforehand.

The Commission 's proposal for the MFF 2021-2027 on 2 May 2018 already made many European capitals nervous. The proposal was 1.11 % of GNI (already excluding the UK). It envisaged budget increases for border control, defence, migration, internal and external security, cooperation with development and research, among other areas. On the other hand, cuts were foreseen in Cohesion Policy (aid to help the most disadvantaged regions of the Union) and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

The Parliament submitted a report provisional on this proposal in which it called for an increase to 1.3% of GNI (corresponding to a 16.7% increase from the previous proposal ). In addition, MEPs called, among other things, for cohesion and agriculture funding to be maintained as in the previous budget framework .

On 2 February 2019 the Finnish Presidency of committee proposed a negotiation framework starting at 1.07% of GNI.

This succession of events led to the emergence of two antagonistic blocs: the frugal club and the friends of cohesion.

The frugal club consists of four northern European countries: Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Austria. These countries are all net contributors and advocate a budget of no more than 1 % of GNI. On the other hand, they call for cuts to be made in what they consider to be "outdated" areas such as cohesion funds or the CAP, and want to increase the budget in other areas such as research and development, defence and the fight against immigration or climate change.

Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz has already announced that he will veto on committee any proposal that exceeds 1 % of GNI.

The Friends of Cohesion comprise fifteen countries from the south and east of the Union: Spain, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. All these countries are net recipients and demand that CAP and cohesion policy funding be maintained, and that the EU's budget be based on between 1.16 and 1.3 % of GNI.

This large group met on 1 February in the Portuguese town of Beja. There they tried to show an image of unity ahead of the first days of the MFP's discussion , which would take place in Brussels on the 20th and 21st of the same month. They also announced that they would block any subject cuts.

It will be curious to see whether, as the negotiations progress, the blocs will remain strong or whether each country will pull in its own direction.

Outside of these two groups, the two big net contributors stand out, pulling the strings of what happens in the EU: Germany and France.

Germany is closer to the frugals in wanting a more austere budget and more money for more modern items such as digitalisation or the fight against climate change. But first and foremost it wants a quick agreement .

France, for its part, is closer to the friends of cohesion in wanting to maintain a strong CAP, but also wants a stronger expense in defence.

The problem of "rebates

And if all these variables were not enough, we have to add the figure of the compensatory cheques or "rebates. These are discounts to a country's contribution to budget. This figure was created in 1984 for the United Kingdom, during the presidency of the conservative Margaret Thatcher. For the "Iron Lady", the amount that her country contributed to budget was excessive, as most of the amount (70%) went to the CAP and the Cohesion Funds, from which the UK hardly benefited. It was therefore agreed that the UK would have certain discounts on its budgetary contribution on a permanent and full basis.

And if all these variables were not enough, we have to add the figure of the compensatory cheques or "rebates. These are discounts to a country's contribution to budget. This figure was created in 1984 for the United Kingdom, during the presidency of the conservative Margaret Thatcher. For the "Iron Lady", the amount that her country contributed to budget was excessive, as most of the amount (70%) went to the CAP and the Cohesion Funds, from which the UK hardly benefited. It was therefore agreed that the UK would have certain discounts on its budgetary contribution on a permanent and full basis.

These compensatory cheques have since been given to other net contributor countries, but these had to be negotiated with each MFF and were partial on a specific area such as VAT or contributions. An unsuccessful attempt was already made to eliminate this in 2005.

For the frugal and Germany these cheques should be kept, on civil service examination to the friends of cohesion and especially France, who want them to disappear.

Sánchez seeks his first victory in Brussels

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is staking much of his credibility in both Europe and Spain on these negotiations.

In Europe, for many he failed in the negotiations for the new Commission. Sánchez started from a position of strength as the leader of Europe's fourth Economics after the UK's exit. He was also the strongest member of the Socialist group parliamentary , which has been in the doldrums in recent years at the European level, but was the second strongest force in the European Parliament elections. For many, therefore, the election of the Spaniard Josep Borrell as High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, with no other socialist in key positions, was seen as a failure.

Sánchez has the opportunity in the negotiations to show himself as a strong and reliable leader so that the Franco-German axis can count on Spain to carry out the important changes that the Union has to make in the coming years.

On the other hand, in Spain, Sánchez has the countryside up in arms over the prospects of reducing the CAP. And much of his credibility is at stake after his victory in last year's elections and the training of the "progressive coalition" with the support of Podemos and the independentistas. The Spanish government has already taken a stand with farmers, and cannot afford a defeat.

Spanish farmers are highly dependent on the CAP. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food: "in 2017, a total of 775,000 recipients received 6,678 million euros through this channel. In the period 2021-2027 we are gambling more than 44,000 million euros."

There are two different types of CAP support:

-

Direct aids: some are granted per volume of production, per crop (so called "coupled"), and the others, the "decoupled" ones, are granted per hectare, not per production or yield and have been criticised by some sectors.

-

Indirect support: this does not go directly to the farmer, but is used for the development of rural areas.

The amount of aid received varies depending on the sector, but can amount to up to 30 % of a farmer's income. Without this aid, a large part of the Spanish countryside and that of other European countries cannot compete with products coming from outside the Union.

Failure of the first budget summit

On 20 and 21 February an extraordinary summit of the European committee took place in order to reach a agreement. It did not start well with the proposal of the president of the committee, Charles Michel, for a budget based on 1.074% of GNI. This proposal convinced nobody, neither the frugal as excessive, nor the friends of cohesion as insufficient.

Michel's proposal included the added complication of linking the submission of aid to compliance with the rule of law. This measure put the so-called Visegrad group (Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia) on guard, as the rule of law in some of these countries is being called into question from the west of the Union. So, another group is taking centre stage.

The Commission's technical services made several proposals to try to make everyone happy. The final one was 1.069% of GNI. Closer to 1%, and including an increase in rebates for Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Austria and Denmark, to please the frugal and attract the Germans. But also an increase in the CAP to please the friends of cohesion and France, at the cost of reducing other budget items such as funding for research, defence and foreign affairs.

But the blocs did not budge. The frugal ones remain entrenched at 1%, and the friends of cohesion in response have decided to do the same, but at the 1.3% proposed by the European Parliament (even if they know it is unrealistic).

In the absence of agreement Michel dissolved the meeting; it is expected that talks will take place in the coming weeks and another summit will be convened.

Conclusion

The EU has a problem: its ambition is not matched by the commitment of its member states. The Union needs to reinvent itself and be more ambitious, say its members, but when it comes down to it, few are truly willing to contribute and deliver what is needed.

The Von der Leyen Commission arrived with three star plans: the European Green Pact to make Europe the first carbon-neutral continent; digitalisation; and, under Josep Borrell, greater international involvement on the part of the Union. However, as soon as the budget negotiations began and it became clear that this would lead to an increase in the expense, each country pulled in its own direction, and it was these subject proposals that were the first to fall victim to cuts due to the impossibility of reaching an understanding.

A agreement has to be reached by 31 December 2020, if there is to be no money at all: neither for CAP, nor for rebates, nor even for Erasmus.

Member States need to understand that for the EU to be more ambitious they themselves need to be more ambitious and willing to be more involved, with the increase in budget that this entails.