Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

[Marko Papic, Geopolitical Alpha. An Investment Framework for Predicting the Future (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2021), 286 pages].

review / Emili J. Blasco

"In the post-Trump and post-Brexit era, geopolitics is all that counts," says Marko Papic in Geopolitical Alpha, a book on political risk whose purpose aims to provide a method or framework from work for those involved in foresight analysis. consultant in investment funds, Papic condenses here his experience in a profession that has gained attention in recent years due to growing national and international political instability. development Whereas risk factors used to be concentrated in emerging countries, they are now also present in the advanced world.

With the book's degree scroll , Papic designates a process of analysis in which geopolitics proper, in its most geographically related sense, is only one part of the considerations to be taken into account, as the author argues that political and then economic (and financial) determinants matter first. For the whole of the analysis and the estimates it gives rise to, Papic uses the qualifier "alpha geopolitics" (or "alpha geopolitics"), as referring to a plus or reinforced geopolitics: one that takes into account political or macroeconomic constraints in addition to traditional geopolitical imperatives.

With the book's degree scroll , Papic designates a process of analysis in which geopolitics proper, in its most geographically related sense, is only one part of the considerations to be taken into account, as the author argues that political and then economic (and financial) determinants matter first. For the whole of the analysis and the estimates it gives rise to, Papic uses the qualifier "alpha geopolitics" (or "alpha geopolitics"), as referring to a plus or reinforced geopolitics: one that takes into account political or macroeconomic constraints in addition to traditional geopolitical imperatives.

At bottom it is a nominalist question, in a collateral battle in which the author unnecessarily entangles himself. It is arguably a settling of scores with his former employer, the George Friedman-led Stratfor, whom Papic praises in his pages, but who he seems to covertly criticise for basing much of his foresight on the geography of nations. To suggest that, however, is to make a caricature of Friedman's solid analysis. In any case, Papic has certainly reinforced his training with programs of study financials and makes useful and interesting use of them.

The central idea of the book, leaving aside this anecdotal rivalry, is that in order to determine what governments will do, one should look not at their stated intentions, but at what constrains them and compels them to act in certain ways. "Investors (and anyone interested in political forecasting) should focus on material constraints, not politicians' preferences," says Papic, adding a phrase that he repeats, in italics, in several chapters: "Preferences are optional and subject to constraints, while constraints are neither optional nor subject to preferences.

These material constraints, according to the order of importance established by Papic, are political conditioning factors (the majority available, the opinion of the average voter, the level of popularity of the government or the president, the time in power or the national and international context, among other factors), macroeconomic and financial constraints (budgetary room for manoeuvre, levels of deficit, inflation and debt, value of bonds and currency....) and geopolitical ones (the imperatives that, derived initially from geography - the particular place that countries occupy on the world stage - mark the foreign policy of nations). To that list, add constitutional and legal issues, but only to be taken into account if the aforementioned factors do not pose any constraint, for it is well known that politicians have little trouble circumnavigating the law.

The author, who presents all this as a method or framework of work, considers that the fact that there may be irrational politicians who entrance do not submit to objective material constraints does not derail the approach, since this status is eventually overcome because "there is no irrationality that can alter reality". However, he admits as a possible objection that, just as the opinion of the average voter conditions the actions of the politician, there may be a "hysterical society" that conditions the politician and is not itself affected in the short term deadline by objective constraints that make it bend to reality. "The time it takes for a whole society to return to sanity is an unknown and impossible prognosis," he acknowledges.

Papic proposes a reasonable process of analysis, broadly followed by other analysts, so there is no need for an initial, somewhat smug boast about his personal prospective skills, which are indispensable for investors. Nevertheless, the book has the merit of a systematised and rigorous exhibition .

The text is punctuated with specific cases, the analysis of which is not only well documented but also conveniently illustrated with tables of B interest. Among them is one that presents the evolution of pro-euro opinion in Germany and the growing Europhile position of the average German voter, without which Merkel would not have reached the previously unthinkable point of accepting the mutualisation of EU debt. Or those that note how England, France and Russia's trade with Germany increased before the First World War, or that of the United States with Japan before the Second World War, exemplifying that rivalry between nations does not normally affect their commercial transactions.

Other interesting aspects of the piece include his warning that "the class average will force China out of geopolitical excitement", because international instability and risk endangers Chinese economic progress, and "keeping its class average happy takes precedence over dominance over the world". "My constraint-based framework suggests that Beijing is much more constrained than US policymakers seem to think (...) If the US pushes too hard on trade and Economics, it will threaten the prime directive for China: escape the middle-income trap. And that is when Beijing would respond with aggression," says Papic.

Regarding the EU, the author sees no risks for European integration in the next decade. "The geopolitical imperative is clear: integrate or perish into irrelevance. Europe is not integrating because of some misplaced utopian fantasy. Its sovereign states are integrating out of weakness and fear. Unions out of weakness are often more sustainable in the long run deadline. After all, the thirteen original US colonies integrated out of fear that the UK might eventually invade again.

Another suggestive contribution is to label as the "Buenos Aires Consensus" the new economic policy that the world seems to be moving towards, away from the Washington Consensus that has governed international economic standards since the 1980s. Papic suggests that we are exchanging the era of "laissez faire" for one of a certain economic dirigisme.

The nascent English kingdom consolidated its power across the English Channel at civil service examination , giving rise to a particularism that is particularly vivid today.

With no turning back now that Brexit has been consummated, Britain is seeking to establish a new relationship with its European neighbours. Its departure has not been supported by any other country, which means that London has to come to terms with a European Union that remains a bloc. Despite the drama with which many Europeans have greeted Britain's farewell, this is yet another chapter in the complex relationship that a large island has with the continent to which it is close. Island and continent remain where geography has placed them - at a distance of particular value - and are likely to reproduce vicissitudes already seen throughout their mutual history.

Fragment of the Bayeux tapestry, illustrating the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

article / María José Beltramo

The result of the 2016 referendum on Brexit may have come as a surprise, as the abrupt manner in which the UK finally and effectively left the European Union on 31 December 2020 has undoubtedly come as a surprise. However, what we have seen is not so alien to the history of the British relationship with the rest of Europe. If we go back centuries, we can see a geopolitical patron saint that has been repeated on other occasions, and also today, without having to speak of determinism.

Although it is worth mentioning some previous moments in the relationship of insular Britain with the continent next to it, such as the period of Romanisation, the gestation of the patron saint which at the same time combines linkage and distancing, or even rejection, can perhaps be placed at the beginning of the second millennium, when the Norman invasions across the English Channel consolidated the nascent kingdom of England precisely against the power of the other side of the Channel.

England in Norman times

Normandy became a political entity in northern France when in 911, following Viking invasions, the Norman chief Rolon reached an agreement with the Frankish king, agreement , guaranteeing him the territory in exchange for its defence[1]. 1] Normandy became a duchy and gradually adopted the Frankish feudal system, facilitating the gradual integration of the two peoples. This intense relationship would eventually lead to the full incorporation of Normandy into the kingdom of France in 1204.

Before the gradual Norman dissolution, however, the Scandinavian people settled in that part of northern France carried their particular character and organisational capacity, which ensured their independence for several centuries, across the English Channel.

The Norman-English relationship began in 1066 with the Battle of Hastings, in an invasion that led to the Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror, being crowned King of England in London. The arrival of the Normans had a number of consequences. Politically, they brought the islands into the European relations of the time and brought English feudalism into line with Norman feudalism, a mixture that would lay the foundations for future English parliamentarianism instructions . In terms of Economics, the Normans demonstrated their Scandinavian organisational skills in the reorganisation of productive activities. In their different conquests, the Normans knew how to take the best of each system and adapt it to their culture and needs, and this was the case in England, where they developed a particular idiosyncrasy.

With this takeover of contact with the continent, England began to consolidate as a monarchy, while retaining its links with the Duchy of Normandy. However, with its strengthening after the fall of the Plantagenets in France, England gained the momentum it lacked to finally become an independent kingdom, completely separate from the continent, detached from a Normandy whose lineage was weak and in a critical state. Indeed, the Kingdom of France's absorption of the Norman duchy facilitated the development and consolidation of the English monarchy as an independent and strong entity[2].

The separation from the European continent brings us back to Ortega y Gasset's analysis of European decadence and the moral crisis it is going through[3]. The continental powers, being in a status of geographical continuity, and therefore in greater contact, are more likely to spread their status among themselves and to be dominated by another major power. England, having broken the bridge of feudal ties that connected it with the rest of Europe, finds no difficulty in distancing itself when it sees fit, always in its own interests, something we see repeated several times throughout its history. This is particularly evident in the vicissitudes that punctuate the UK's relationship with the continent throughout the final decades of the second millennium.

The English status since 1945

The Second World War greatly weakened the UK, not only economically but also as an empire. In the process of decolonisation that followed, London lost possessions in Asia and Africa, and the Suez Canal conflict confirmed its decline as a major player to its successor as the world's leading power, the United States. The post-war confrontation with the Soviet Union and the US presence in Europe meant that the transatlantic relationship was no longer based on Washington's preferential link with Britain, so the role of the British also declined[4].

In 1957 France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg created the European Economic Community (EEC). The Conservative Harold MacMillan, British Prime Minister from 1957 to 1963, refused to include the United Kingdom in the initiative, but aware of the need to revitalise the British Economics and "the difficulty of maintaining a policy that was alien to European interests", he promoted the creation of the EFTA (European Free Trade Association) in 1959, together with Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, Austria and Portugal.

The Common Market proved to be a success and in 1963 the UK considered joining, but was blocked by de Gaulle's France. In 1966 the British again submitted a proposal application, but it was again rejected by de Gaulle. The French general's conception of Europe did not include the Atlantic bloc; he still envisaged building Europe on a Franco-German axis.

The 1970s saw a directional shift in European politics. The British Conservatives won the 1970 elections and in 1973 Britain joined the EEC. The international economic crisis, which was particularly difficult in the UK, led Labour, back in power, to propose a review of the terms of membership and Premier Harold Wilson called a referendum in 1975: 17 million Britons wanted to remain (67% of voters) compared with only 8 million who called for a first Brexit.

However, when the European Monetary System (EMS) was launched in 1979 to equalise currencies and achieve "economic convergence", the UK decided not to join this voluntary agreement . Europe was experiencing a gradual economic boom, but the UK's Economics was not keeping pace, which partly led to the early elections of 1979. These were won by the Conservatives with Margaret Thatcher, who remained in Downing Street until 1990. The Thatcher revolution "marked the way out of the crisis of the 1970s". In 1984, London reduced its contribution to EU funds and Thatcher, very reluctant to accept EU budgets and other procedures that reduced national sovereignty, again called for a review of the agreements.

In 1985 the Schengen Agreements were signed (the opening of borders between certain countries creating a kind of much wider second border), which came into force ten years later. Again, the UK stayed out of it. As was also the case in relation to the euro, when the single currency came into effect in 2002, maintaining the pound sterling to this day.

Immigration from Central and Eastern European countries following the 2004 EU enlargement, accepted by Labour's Tony Blair, and the acceleration of financial harmonisation mechanisms in the wake of the 2008-2011 crisis, met with displeasure by the Conservative David Cameron, provided arguments for the anti-EU speech in the United Kingdom. This led to the rise of the anti-European UKIP and the subsequent adoption of its positions by broad Tory sectors, eventually amalgamated by the controversial personality of Boris Johnson.

In an interview with the BBC in 2016, Johnson referred to many of the arguments used in favour of Brexit, such as the UK's dialectical vision of its relationship with the continent or the fear of losing sovereignty and the dissolution of its own profile into the European magma. The premier returned to these ideas in his message to the British people as the country prepared to begin its final year in the EU. His words were in some ways an echo of a centuries-old tug-of-war.

Repeating patterns

As we have seen, England has always maintained its own rhythm. Its geographical separation from the continent - far enough away to be able to preserve a particular dynamic, but also close enough to fear a threat, which was sometimes effective - determined the distinctly insular identity of the British and their attitude towards the rest of Europe.

We are dealing with a power that throughout history has always sought to maintain its national sovereignty at all costs and whose geopolitical imperative has been to prevent the continent from being dominated by a rival great power (the perception, during the 2008 crisis management , that Germany was once again exercising a certain hegemony in Europe could have fuelled the Brexit).

Perhaps in the medieval period, we cannot link this to a thought-out political strategy, but we do see how unintentionally and circumstantially, from the outset, certain conditions are in place that favour the distancing of the island from the mainland, although without radically losing contact . In more recent history we observe this same distant attitude, this time premeditated, in pursuit of interests focused on the search for economic prosperity and the maintenance of both its global influence and its national sovereignty.

[1] Charles Haskins, The Normans in European History (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1915).

[2] Yves Lacoste, Géopolitique : La longue histoire d'aujourd'hui (Paris: Larousse, 2006).

[3] José Ortega y Gasset, La rebelión de las masas (Madrid: Alianza publishing house, 1983).

[4] José Ramón Díez Espinosa et al., Historia del mundo actual (desde 1945 hasta nuestros días), (Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid, 1996).

Attempt by both to reposition France at the geostrategic centre of Europe, with civil service examination from Germany.

Napoleon Bonaparte's nephew and the current president of the French Republic are not entirely parallel lives, but there are some suggestive similarities between the two. It is often said that French presidents revive some of the longed-for packaging of the decapitated monarchy; in Macron's case there is probably a lot of that, but also the assumption of geopolitical imperatives already evident in the Second Empire.

Napoleon III in uniform in an 1850 portrait, and Macron in his New Year's Eve 2019 televised message.

article / José Manuel Fábregas

Emmanuel Macron's decision to hold the G7 summit in the French Basque town of Biarritz in August 2019 brought about a symbolic rapprochement with the figure of Napoleon III. The emperor, and nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, transformed the former fishing village into a cosmopolitan holiday resort where European aristocrats and members of the international political elite gathered. Macron, for his part, has put Biarritz back on the stage of the world's major political discussions.

Thus two personalities come together who, with the attraction of having been the youngest heads of state in the country, share two fundamental aspects in their understanding of French politics. First, the influence that their childhood has had on both of them in developing a personalist way of understanding the head of state. And second, how both have tried to reposition France at the geostrategic centre of Europe and have been blocked by Germany.

What is the role of the head of state?

Born fifth in the order of Napoleon I's succession, the young Louis Napoleon Bonaparte never foresaw that he would become heir to the imperial house in 1832. According to his biographer Paul Guériot, his mother, Hortense de Beauharnais, instilled in him from an early age the idea that he was destined to rebuild the now-defunct Napoleonic Empire. His mother's insistence that he had a perfect intellectual and military training transformed Louis Napoleon - who received Education from the Jacobin, and follower of Robespierre, Philippe Le Bas - into a solitary, shy and megalomaniacal person obsessed with restoring Napoleonic France[1].

The revolution of February 1848, according to Jacob Talmon, was inevitable "although it was, nevertheless, an accident"[2]. The Israeli historian explains that the uprisings in various parts of Europe were a direct reaction to the territorial reordering of the Vienna congress (1815). In this context of discontent or disillusionment with the Restoration system, the figure of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte may have benefited from the image of a romantic revolutionary assigned to him by the newspapers and opinion writings of the time. After failed coup attempts in Strasbourg (1836) and Bologna (1840), the future emperor spent a brief period in prison. This was a determining factor in the construction of the romantic hero character that aroused such admiration in a society that loved the novels of Alexandre Dumas[3]. The exploitation of this personality by means of a huge propaganda apparatus enabled him to win the elections of December 1848 by a landslide. Thus, it could also be said that the establishment of the Second Empire - ratified by a popular plebiscite in November 1852 - was the next step in his main political project : the revival of Napoleonic France.

For his part, the current president of the French Republic also experienced an overprotective childhood that forged, like the last emperor of France, a solitary personality and an individualistic way of understanding politics. Anne Fulda stresses in her biography of Emmanuel Macron that, being born a year after the death of his older sister and after a complicated birth, his birth was considered a miracle. This may have fostered, along with a competitive Education in which he excelled as a 'child prodigy', his self-conviction that he was destined to rule the country[4]. However, his election as head of state was not the fruit of a long-term strategy deadline, but rather, like Louis Napoleon's, a tactical move. Macron's image of renewal was cleverly exploited in an election in which he faced rivals with certain communicative weaknesses, such as those with a low profile like François Fillon (Republican) and Benoît Hamon (Socialist), or others with more extremist tones like Marine Le Pen (National Front) and Jean-Luc Mélenchon (Unsubmissive France).

In 2015, while still minister of Economics, Emmanuel Macron made an interesting reflection for the weekly Le 1 on the role of the president in France. He understood that French citizens felt a lack after the fall of the monarchy, which they had tried to fill by strengthening the figure of the president. This excessive weight of personalism in Macron's understanding of politics has also been demonstrated recently in the replacement of Édouard Philippe as prime minister. Because the latter's popularity had grown over the last year as he had shown himself to be more charismatic and calm in contrast to the president's overacting and abusive protagonism, Macron chose Jean Castex as his replacement, with a more technocratic profile that does not overshadow the president in the face of his re-election.

What role France should play in Europe

This firm commitment by both leaders to give greater importance and visibility to the position head of state transcends the borders of France. Napoleon III and Emmanuel Macron also share the desire to place France at the centre of the European balance.

Having won the elections with a speech against the order inherited from the congress of Vienna, Napoleon III had his own European project based on the free integration or separation of the different national identities of the old continent. A clear example of this was the Crimean War (1854-1856). Fearing that the declining Ottoman Empire would end up as a vassal of Russia, the emperor defended, together with the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Sardinia, its independence from the Ottomans in a conflict that would temporarily separate Russia from the other Western powers[5]. 5] The Treaty of Paris (1856) would not only end the war, but also motivate Napoleon III to initiate an interventionist policy in Europe.

Napoleon III's imperial dream forced him to develop an active foreign policy focused on expanding France's borders and reordering the continent with two main values in mind: nationalism and liberalism. However, Henry Kissinger rightly remarks that his diplomatic work was so confused that "France got nothing"[6]. By supporting the unification of Italy at the cost of the Austrian Empire's loss of territory, Napoleon unwittingly favoured the creation of Germany. These events severely weakened France's geostrategic influence in the new European order to which he aspired. In contrast, it was Bismarck's clever diplomatic tactics that would really put an end to the Vienna system, hastening the fall of the Second French Empire at the Battle of Sedan (1870).

Alongside this, Emmanuel Macron is presenting himself as the saviour of the European Union in a context marked by the rise of populist and Eurosceptic movements. However, his ambitious reform projects have met with Angela Merkel's reluctance.

In a recent interview for The Economist, Emmanuel Macron said that NATO was "brain-dead" and that Europe was "on the edge of a precipice" because of its dependence on the United States and lack of independence in terms of defence. Macron opted for greater EU integration in the strategic field, going so far as to propose a single pan-European army. In response, German Chancellor Angela Merkel objec ted that Europe does not currently have the capacity to defend itself and is therefore dependent on the Atlantic Alliance. In addition, Macron has also challenged the apparent agreement among EU member states over membership and the relationship with Russia. The French president's veto of Albania and North Macedonia's possible membership, on the grounds that they did not comply with EU corruption clauses, has even been described as a 'historic mistake', leaving the future of the Balkan countries at the mercy of Russia and China. This position is not shared by Russia, with which he is willing to ease diplomatic relations and even suggests further integration of the country into Europe.

On final, Emmanuel Macron and Napoleon III share an excessively egocentric vision. The overexposure of certain personal characteristics in matters of state and the excessive claim to leadership in Europe are two aspects common to these two young leaders. While historiography has already judged the mistakes that precipitated Louis Napoleon into exile, it remains to be seen whether or not Macron is doomed to repeat the history of his predecessor.

[1] Guériot, P. (1944). Napoleon III. Madrid: Ediciones Técnicas.

[2] Talmón, J.L. (1960). Political messianism. La etapa romántica. Mexico City: Ed. Aguilar.

[3] Guériot, P. (1944). Napoleon III. Madrid: Ediciones Técnicas.

[4] Fulda, A. (2017). Emmanuel Macron, the president who has surprised Europe. Madrid: Ediciones Península.

[5] Milza, P. (2004). Napoleon III. Paris: Éditions Perrin.

[6] Kissinger, Henry (1994). Diplomacy (First Edition). Barcelona: Ediciones B.

[Daniel Méndez Morán, 136. China's plan in Latin America (2018), 410 pages].

review / Jimena Puga

By means of a first-person on-the-ground research and the testimony staff of Chinese and Latin Americans, who give the story the character of a documented report, Daniel Méndez summarises in detail the mark that the growing Asian superpower is leaving in the region. This gives the reader an insight into the relations between the two cultures from an economic and, above all, political point of view. The figure of degree scroll -136- is the issue that, according to the author, Beijing assigns to its plan for Latin America, in its planning of different sectoral and geographical expansion programmes around the world.

The book begins by briefly reflecting on China's rapid growth since the death of Mao Zedong and thanks to Deng Xiaoping's growth and opening-up policies between 1980 and 2000. This resurgence has not only been reflected in China's Economics but also in society. The new generations of Chinese professionals are better educated training and more fluent in foreign languages than their elders, and therefore better prepared for International Office. However, Liu Rutao, Economic and Commercial Counsellor at the Chinese Embassy in Chile explains to the author that "the history of China's going abroad is only fifteen years old, so neither the government nor the companies have a very mature thinking on how to act abroad, so we all need to study".

However, the country's short experience in the international arena is not an obstacle since, as the book shows, China has a very effective shortcut to accelerate this learning process: money. In fact, the goal of many of the most important Chinese investments in Latin America is not only access to natural resources, but also to human capital and, above all, to knowledge. Thanks to their huge financial resources, Chinese companies are acquiring companies with experience and contacts in the Americas, hiring the best professionals in each country and buying brands and technologies. "This phase is very difficult. Chinese companies are going to pay to learn. But everything is learned by paying," diplomat Chen Duqing, China's ambassador to Brazil between 2006 and 2009, explained to Méndez.

After this overview, the book moves on to China's relationship with different Latin American partners. In the case of Mexico, there is a struggle against the famous made in China. The empire at the centre went to Mexico 40 years ago to study the maquiladora programme; when they returned, Méndez explains, they said: "Mexico is doing that for the United States, we are going to do it for the world". And so, a few years later, China designed and improved the strategy. There is little doubt that made in China has won the day over Mexican maquiladoras, and it is all these decades of skill and frustration that explain the complex political relations between the two countries. This is what the people interviewed by the author testify to. To Jorge Guajardo, this model reminds him of the colonial order imposed by Spain and continued by the United Kingdom: "I sometimes said to the Chinese: 'Gentlemen, you cannot see America: Gentlemen, you cannot see Latin America as anything other than a place where you go for natural resources and in return you send manufactured goods. We were already a colony. And we didn't like it, it didn't work. And we chose to stop being one. You don't want to repeat that model".

The result of these new tensions is that neither country has achieved what it was looking for. Mexico has barely increased its exports to China and the Asian giant has barely increased its investments in the Latin American country. In 2017 there were only 30 Chinese companies installed in Mexico, a very small number compared to the 200 in Peru. Other diplomats on the continent recognise that in any international meeting where both countries are present, the Latin American country is always the most reluctant to accept Beijing's proposals. For China, Mexican 'resistance' is perhaps its biggest diplomatic stumbling block in the region: the best example that its rise has not benefited all countries in the South.

Méndez says that, unlike Mexico, Peru's mining strategy has found an ideal partner on the other side of the Pacific. In need of minerals to feed its industry and build new cities, China's huge demand has pulled strongly on the Peruvian Economics . Between 2004 and 2017, trade between the two countries increased tenfold and the Asian giant became Peru's first commercial partner . China is no longer only important for its demand for copper, lead and zinc, but also for its investment flows and its capacity to implement mining projects. These financial conditions, which are very difficult to obtain from private banks, are often the comparative advantage that allows Chinese state-owned companies to beat their Western competitors.

What does this mean for Latin America, and should Latin American countries be concerned about this political and economic strategy that invests massively in their natural resources through state-owned companies? As the book points out, many diplomats think it is necessary to be vigilant. Unlike private companies, whose primary goal aim is to make profits and submit dividends to their shareholders, Chinese companies are ultimately written request controlled by politicians who may have another diary. In this sense, the expansion of so many state-owned companies in natural resources can also become a weapon of pressure and influence.

If a Latin American leader, for example, decides to meet with the Dalai Lama or opposes a diplomatic initiative led by Beijing, the Asian giant could use its state-owned companies in retaliation, warns Méndez. In the same way that if the Peruvian government wanted to cancel some project chimo for labour or environmental infractions, Beijing could threaten to deny approval of phytosanitary protocols or delay other investments. Moreover, China is increasingly aware that its image, its capacity for persuasion and its cultural attractiveness (soft power) are vital to expand its political and economic project .

On the other hand, further south in the region, Uruguay has become the perfect laboratory for China. Uruguayan factories are prepared for short production runs of a few thousand cars, the country has a specialised workforce and the good infrastructure means that in a very short time it is possible to set up plants in Brazil or Argentina. It should be borne in mind that Chinese companies are still little known in Latin America and do not have many financial resources, and in Uruguay they can test the market.

As for Brazil, Méndez speaks especially of the diplomacy of satellites. Satellites are not only useful for bringing television to homes and for using GPS on mobile phones, but also for their military capabilities and the political prestige they imply. Brazil has collaborated with other countries such as Argentina and the United States, but political and economic tensions almost always limit space cooperation. Paradoxically, in the case of China, distance seems to be a blessing as there are no geopolitical problems between the two: sometimes it is more difficult to work with your neighbours than with people who are far away. For Beijing, space missions serve to enhance all dimensions of its power: it increases its military capabilities and contributes to its space industry and competitiveness in an economic sector with a bright future. And finally, it also serves as a public relations campaign in the world. However, the technological and economic differences are becoming so apparent that even China is outgrowing the South American giant.

From a geostrategic point of view, Méndez does not want to miss the construction of a Chinese space station on a 200-hectare plot of land in the Argentinean province of Neuquén, which has an initial investment of 50 million dollars and is part of China's moon exploration programme. Moreover, Argentina is the only country in which the presence of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China is so popular in society. B . This Chinese bank has managed to offer the same services as any other banking institution in Argentina.

Finally, Chile is one of the countries with which Beijing has the best relations, but why does China not invest in Chile? The answer is simple. Investment processes in Chile are clear, transparent and equal for all countries. There are no exceptions and investors have to follow complex legal regulations to the letter. The business culture is different, and the Chinese don't like the idea of needing lawyers and 20,000 permits for everything. They like to pay bribes, and in Chile corruption provokes a lot of indignation.

Throughout this country-by-country analysis, the author has made one thing clear: China has a plan. Or at least, it has been able to bet for decades on the training of officials with the goal of designing a strategy in Latin America. This capacity for planning and these long-term objectives deadline have helped the Asian giant to advance its position in recent years and leave a deep mark on many countries in the American continent. And what does the plan consist of? It is clear that China's goal issue one is economic. It has managed to successfully "sneak" into the three major trade blocs that include Latin American countries: NAFTA, the Pacific Alliance and Mercosur.

But Economics per se is not the only thing that drives China. To achieve its economic goals, Beijing also needs to build political relations and allies that can defend its diplomatic positions. Its defence of non-interference in internal affairs and a multipolar world demands in return the silence of Latin American countries on human rights violations in their country and respect, for example, for the one-China policy. The Asian giant wants to expand all its strengths and is not willing to give up any of them.

In conclusion, whether or not China has a strategy for Latin America, Latin America does not have a strategy for China. And China is not an NGO; if recent history shows anything, it is that each country seeks to defend its own selfish national interests at the International Office level. China has its diary and is pursuing it. Perhaps the time has come for Latin America to have its own.

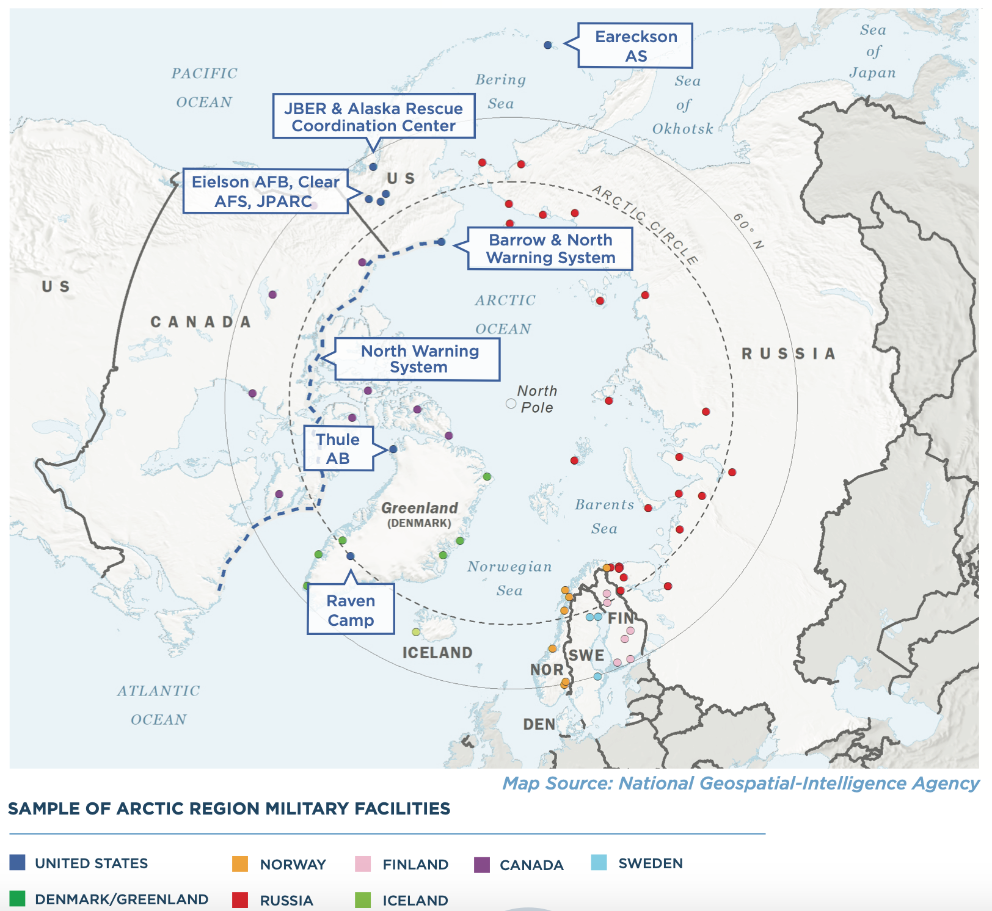

Prepare to project "credible combat power" in the new era of "strategic competition".

If the Arctic was an important stage in the Cold War, in the new geopolitical tension its progressive thawing even accentuates its strategic characteristics. In 2019, the US Defence department adapted its Arctic strategy to the new rivalry with Russia and China, and then it was up to the forces most involved in the region to implement it: in 2020 the Air Force presented its own document and in 2021 the Navy did so, also involving the Marine Corps and the Coast Guard. The guidelines seek to ensure the projection of "credible combat power".

The crew of the submarine USS Connecticut at the ICEX 2020 exercises [US Navy].

article / Pablo Sanz

The Arctic is important because of the untapped natural wealth contained in its subsoil (22% of the world's hydrocarbon deposits, or 90 billion barrels of oil) and because of its strategic position on the globe: the two great continental masses of Eurasia and America converge here. The opening of new maritime routes thanks to the progressive melting of the ice is not only a commercial advantage, but also makes it possible to act militarily more quickly in this and other scenarios.

Many countries are interested in promote cooperation and multilateralism in the region, and this is done from the committee Arctic; however, the complex security environment of the Arctic Circle has led the major powers to set strategies to defend their respective interests. In the case of the United States, the Defence department updated in June 2019 the Arctic strategy it had developed three years earlier, in order to bring it into line with the new approach that emerged with the 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS) and carried over into the 2018 National Defence Strategy (NDS), documents that leave behind the era of combating international terrorism and elevate the relationship with China and Russia to 'rivalry', in a new geopolitical status of 'strategic competition'.

The Pentagon's strategy for the Arctic was then fleshed out by the air force in its own report , presented in July 2020, and then by the navy in January 2021. Along the same general lines, these approaches framework are aimed at three objectives:

1) As an "Arctic nation", because of its sovereignty over Alaska, the United States must ensure security in its territory and prevent polar positions from threatening other parts of the country.

2) The United States seeks to establish and lead alliances and agreements in the Arctic in accordance with international law in order to maintain a stable status in the area.

3) The United States commits to preserving free navigation and overflight in the Arctic Circle, while limiting Russian and Chinese interference contrary to this general freedom of access and transit.

To achieve these objectives, the Pentagon has defined three mechanisms for action:

i) Raising awareness of the importance of the area: the ability of the Defence department to detect threats in the Arctic is a prerequisite for deterring or responding to activities of strategic competitors in the region.

ii) Enhance and promote operations in the Arctic: department Defence will improve the ability of its forces to operate in the Arctic through regular exercises and deployments to the region, both independently and with allies. Some exercises will be conducted within the NATO context while others will be bilateral or multilateral.

iii) Strengthen the rules-based order in the Arctic: department Defence will continue to work with US allies to maintain and strengthen the freedom of navigation and overflight regime. This will help deter aggressive acts in the area.

From the new NDS the Defence department states that the US military must be able to solve the main problem identified - the erosion of the competitive edge against China and Russia - by being able to "deter and, if necessary, defeat great power aggression". To do so, it must develop a force that is "more lethal, resilient, agile and ready", which in the Arctic region must achieve "credible deterrent power".

US military doctrine warns that the Arctic's character as a 'strategic buffer' is 'eroding', becoming 'a pathway of threat to national territory due to the advances of competing great powers'. It also 'hosts critical launching points for global power projection and increasingly accessible natural resources'. However, it warns that "the immediate possibility of conflict is leave".

Thus, in the context of implementing the national defence strategy, the Pentagon states that it will continue to prepare its units to ensure that the Arctic is a secure and stable region in which US national interests, regional security and the work joint efforts of the nations involved to address common problems are safeguarded.

The US Air Force and Navy documents outline supporting measures to ensure the ability to deter hostile actions in the Arctic by other regional competitors in the area, while prioritising a cooperative and continuous approach that preserves the rules by which the Arctic is governed.

Air and sea

Because the Gulf of Mexico current heads towards the European side of the Arctic, the North American side of the Arctic suffers even harsher environmental conditions, with less maritime infrastructure and land routes. As a result, the Air Force's role in the defence of this area is clearly greater, accounting for 80% of the resources the Pentagon devotes to the region.

Its operations are based at a number of locations. Six of these are in Alaska: the large airborne instructions at Elmendorf-Richardson and Eielson; the early missile notice facility at Clear and the missile defence radar at Eareckson; and other coordination, training and survival school sites. Two others are in Greenland: the Raven training range for LC-130 aircraft and the Thule early missile notice site. In Canada, it has a system of some fifty radars shared by NORAD (North American Air Defence Command).

The air force intends to improve these capabilities, as well as command, control, communications, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (C3ISR) capabilities. It has also set goal to enhance refuelling conditions. Once the F-35 deployment at Eielson is complete, Alaska will host more advanced fighters than any other location in the world.

For its part, the US Navy is positioning itself around the concept of the "Blue Arctic", thus graphically expressing the progressive homologation with the rest of the world's oceans of what has historically been an impassable white cap. The navy envisages increasing its presence, both with manned ships and new unmanned vessels. In its strategy document, it warns that the research in new capabilities "may not be fully realised and integrated into the naval force for at least a decade".

The increased naval presence in the region will also be realised through increased operations already routinely conducted in the Arctic by the Second and Sixth Fleets and through synchronisation with the Marine Corps and Coast Guard based in Alaska. To ensure this operational augmentation, the Navy will undertake an upgrade of docking facilities and attendance for its ships.

The Navy document, which does not specify specific preparations, also does not include the Coast Guard's announced plans for a new fleet of icebreakers. There are currently only two in service and the plan is to build three medium and three heavy icebreakers by 2029.

In doing so, Washington is trying to counter the accelerated efforts of its closest competitors. In July 2020, department warned of growing interest in the Arctic from Russia and China, accusing them of engaging in "increasingly aggressive" competition and lamenting that those countries that want "peace, freedom and democracy", including the United States, have been "naïve".

Russia and China

Russia has the largest land mass and population within the Arctic Circle, a region from which Russia derives 25 per cent of its GDP. No other country has such a permanent military presence above the 66th parallel; no other nation has so many icebreaking ships, a fleet Moscow wants to increase with fourteen new vessels, one of them nuclear-powered.

Russia formed its joint strategic command of the Northern Fleet in December 2014. "Since then, Russia has gradually strengthened its presence by creating new Arctic units, refurbishing old infrastructure and airfields, and establishing new military instructions along the coast. There is also a concerted effort to establish a network of air and coastal defence missile systems, early notice radars, rescue centres and a variety of sensors," according to the US defence report strategic Arctic department . The US also warns that Russia is attempting to regulate maritime traffic in the Northern Route in ways that may exceed its authority under international law.

China, on the other hand, without being an Arctic nation (Mohe, its northernmost city is at the same latitude as Philadelphia or Dublin) wants to be a major player in the region. It is an observer country of the committee Arctic and claims a "near-Arctic nation" status that Washington does not recognise. In 2018 it produced the first white paper on its Arctic policy and has integrated this area into its New Silk Road initiative.

China's diplomatic, economic and scientific activities in the Arctic have grown exponentially in recent years. At the moment its operational presence is limited: it has one Ukrainian-built polar-capable icebreaker (the Xuelong; it has recently built the Xuelong 2), which has sailed in Arctic waters on operations that China describes as research expeditions.

The opening of Arctic sea lanes is in China's interest, as it could shorten trade shipment times to Europe and reduce its dependence on flows through the particularly vulnerable Strait of Malacca.

The opening of Arctic sea lanes is in China's interest, as it could shorten trade shipment times to Europe and reduce its dependence on flows through the particularly vulnerable Strait of Malacca.

Lately, China has been engaging in increased diplomatic activities with the Nordic countries and has research stations in Iceland and Norway, as well as mining resources in Greenland. This highlights Beijing's growing interest in consolidating its presence in the Arctic despite its remoteness from the region.

Russia's great financial capacity also means that it is counting on China to develop energy and infrastructure projects in the region, such as a liquefied natural gas facility in Yamal. According to Frédéric Laserre, an expert on Arctic geopolitics at Laval University, Russia has no choice but to accept Chinese capital to build and develop the infrastructure needed to exploit the resources due to Western economic sanctions.

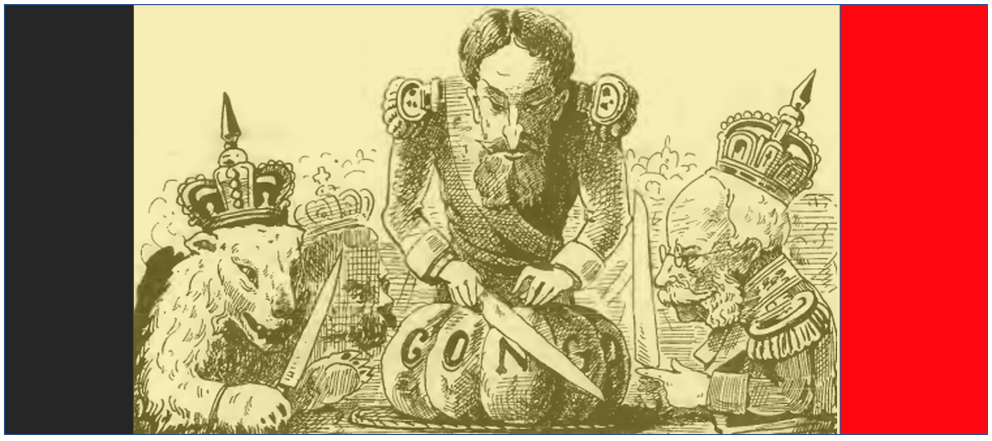

Cartoon depicting Belgian King Leopold II (in the middle) at the Berlin Conference of 1884, by engraver F. Maréchal

COMMENTARY / Cameron Buckingham

The highwaters of the controversy about Belgium's colonial past in Africa, that dominated news at some point in 2020, have receded without Belgian grand institutions taking significant steps to redress the bad reputation. Belgian King Leopold II ordered horrible atrocities throughout the African continent but with the heaviest effect on the Democratic Republic of Congo. The genocide of over six million and slave labour of the Congolese people led by the late Belgian king resulted in immense wealth and can be directly linked to the success of Belgium in the modern-day. In the same way, it can be directly linked to the underdevelopment and continued struggle of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Currently, there has been an international movement to address the racial problems that plague the modern world. Regardless of the organisation or political ideology, it is imperative to acknowledge these problems which stem directly from the unjust colonization, occupation, abuse, and slave trade throughout history. By actively not making any acknowledgment towards this issue, Belgium takes an ignorant stance which not only greatly affects its relations with central African countries, but an international stage speaks to its passive stance on Racism.

In 2019, a working group of experts from the United Nations issued a statement, composed of 74 key points of improvement the country should undertake, to the average with their conclusions of the effects of the colonial past within the country. The Working Group specifically condemned the Belgian government for their lack of engagement with the African minority in their population, as well as their lack of representation in federal institutions and average. The Working Group called on Belgian to improve their education resources so that they accurately portray what truly happened in Africa during colonial and Imperial times. Most importantly they urged Belgium to work on the recognition and social invisibility of people of African Descent, to make a clear and public apology to the African States and adopt a plan of action to confront racism within their country.

Domestic decolonisation

Within the country, the biggest reforms and measures to confront racism are taking place in the capital city of Brussels. One of the biggest changes is the Royal Museum for Central Africa: the museum has taken strides to remove elements of colonialism on display. However, the overall paternalistic attitude of the museum strains the relationship between Belgium and central African countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi. In light of recent events, A statue of Leopold II has been removed by the Antwerp museum after it was set on fire by protestors. There have been many statues defaced by protestors all over Belgium, all calling for his image to be removed from public space as seen in this article Statue of Leopold II, Belgian King Who Brutalized Congo, Is Removed in Antwerp. Simultaneously the government of Brussels has also made attempts to change the names of public spaces or infrastructure that have ties to colonization Most notably seen in a road tunnel, Belgium seeks new name for road tunnel as it takes on colonial past. Brussels has also launched a project to decolonize public space within the city, this was in direct reaction to the BLM movement. This is the most significant action the Belgian state has taken in an attempt to reshape its public history. From road tunnels to parks, the city is making an effort to change. All of these are very pertinent changes as Brussels is the capital city and hopefully, the rest of the nation follows suit. It is equally important to note the work being carried out by the government institution, Inter-Federal Centre of Equal Opportunities (UNIA), which is a public institution that fights discrimination and works to promote equal opportunities for African descendants in Belgium, has acted tremendously to improve the life of African descendants in Belgium.

Despite these advancements, many flaws must be addressed. The Royal Museum of Central Africa chooses certain displays to take down but maintains that history must be preserved. The problem with this is not the artifacts themselves, rather the information and context that turns their public history into a glorification of colonialism. The same can be said for the textbooks and educational resources propagated by the state. The history told in these state resources surrounding the Congolese genocide and the colonisation of Africa do not accurately portray the events and continues a passive ignorant mindset towards this part of their history. It furthers a paternalistic take on history that paints the Belgian leaders as people who were benevolent and brought civilization; when in reality they were brutal oppressors to native populations who exploited and abused central Africa in the name of wealth. While progress is being made, it is not nearly enough considering the global progress and the scale of impact Belgium's colonisation continues to have domestically and internationally.

African reparations

Countries such as Congo and Burundi still have effects today of the violence and loss from the Congolese genocide over a century ago. Their overall underdevelopment and indicators such as HDI, CPI, and GDP can be directly linked to the causes of Belgian colonization. Burundi has asked for $43 billion in reparations, while the Belgian government has yet to offer anything. Other African countries have sought reparations but Belgium has yet to pay any. This is significant because the lack of response and acknowledgment shown by the Belgian government especially during this racially charged period in time points to a blind spot of ignorance of the state. The farthest they have gone to show any sort of repatriation is by returning the tooth of an important political figure in Congo, this information can be accessed here: Belgium to return tooth of assassinated Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba to family | DW | 10.09.2020. This is dismal because it fails to acknowledge the ongoing effects of their colonists' period which paints horribly for their public history in the diplomatic sphere. The Belgian government has an opportunity to better utilize public history for the good of their image, as well as their growth as a country and relations with others however by not taking actions they are hurting themselves. Not only have the economies of these post-colony countries not been able to fully develop, the success of the Belgium economy that is rooted in colonisation creates a twisted paradox for these countries; Their resources and suffering were exploited by an Imperial power who continues to reap the benefits while they are left impoverished and impacted. In this sense, the exploitation of central Africa by Belgium continues today.

Conclusions and recommendations.

Belgium is missing the opportunity to take advantage of such a racially charged time to condemn their past behaviour, acknowledge their impact on Africa, and offer their support to countries they devastated. Belgium should uplift itself by creating a new public history, one that condemns their past. After 11 weeks of social average observation, the Belgium Ministry of Foreign affairs has not posted any content related to racial awareness or their former African colonies. One of the greatest tools today is social average, instead of only posting the glories of their country they should bring awareness to their past, on the biggest platform possible. However, it is not enough to bring light to this issue on social average. It is important to work with other governments, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, to amend and take necessary actions. Belgium needs to consider economic treaties with central Africa that would not only benefit both countries but make reparations for the African states. The goal of Belgian actions should be not only to acknowledge their colonial past but to actively make reparations and accurately acknowledge their atrocities and the impact they have had on central Africa, as well as the impact it's had on Belgian success as a country.

While Belgium ignores their colonial past, surrounding countries such as the Netherlands condemn and continue to actively work against racial cleavages in society. France, in a similar manner, continues to denounce the actions taken by Napoleon Bonaparte and even uses their history to emphasize their strengths not only in times of racial equality but also during coronavirus. With this in mind, it is time for Belgium to step up and meet or exceed the awareness of their neighbours and take actions to address their history and use it as a tool to improve.

ESSAY / Pablo Arbuniés

Introduction

In 1994 both South Africa and Rwanda embarked on a journey of political change that to this day seems unfinished. The first saw the end of apartheid and the beginning of a transition to non-racial democracy, while the latter saw the end of a civil conflict that sparked a genocide.

Both countries faced fundamental changes of a political and social nature at the same time in two very different ways. South Africa faced such change from the perspective of democracy, while Rwanda saw the collapse of a radical ethnic regime under Habyalimana after the civil war in 1994.

Understanding that countries move in a wide spectrum between democracy and non-democracy, that is, that they often are in a liminal political status, is the very basis to study these processes. Comparing these countries that experienced monumental political change at the same time can be useful to understand how societies can be rebuilt after a dark period. Depending on how the transition started, either through force as is the case in Rwanda or via political consensus or constitutional change as in South Africa, the path that the country will follow can vary greatly. It is also worth exploring how a post-conflict consensus can be the basis of a renewed system. Of key interest is how long such dispensation go uncontested and how stable it can sustain the project.

The case of South Africa and Rwanda

South Africa is classified by some as a Flawed Democracy[1], meaning that there are free and fair elections but there are factors that prevent it from arriving at a full democratic rule. In 1990, the government re-established multi-party politics. Then, the 1992 referendum approved universal suffrage, including black people in the democratic process, and the 1994 general elections were the first democratic and universal vote in the history of the country. The African National Congress (ANC) came to power and has won all the following elections.

The ANC-and similarly, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF)-has a sense of exceptionalism, a belief that it has an extraordinary mandate to finish the revolution that only it can fulfil[2]. However, recent elections have shown a decrease in popular support for the ANC. Yet the fact that, over time, the ruling party during a transition process eventually loses free elections is a sign of a consolidated democracy[3].

Rwanda on the other hand is deemed an authoritarian regime by the EIU[4]. In the aftermath of the civil war and the genocide, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) positioned itself as a guarantor of security, consolidating control over all sectors of society. This provision of security and stability in the wake of a conflict, accompanied by an authoritarian use of power, can be referred to as the authoritarian social contract, prioritising security over democracy and fundamental rights, but with a sufficiently transparent and accountable government.

This article will proceed to explore a few indicators like transitional justice, legal framework and institutions, separation of power and rule of law, transparency and accountability plus civil society to test whether South Africa and Rwanda have attained democratic transition through building sustainable political institutions.

Transitional justice

The South African Constitution highlights the importance of healing the consequences of apartheid and establishing a society based on human rights, democracy and social justice. Thus, in 1995 the Government established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), tasked with uncovering past injustices and establishing the truth about the apartheid.

The TRC was composed of three committees: Human rights violations, Reparation and Rehabilitation and Amnesty. Their ultimate goal was to restore the dignity and encourage the spirit of forgiveness between the victims and the perpetrators.

However, in terms of accountability, the TRC has fallen short. The offer of "amnesty for the truth" as well as the de facto back door amnesty provided by the National Prosecuting Authority's Prosecution Policy have meant effective immunity for apartheid-era perpetrators even if they did not apply for amnesty nor helped the TRC. Even after the "back door" was declared unconstitutional in 2008, none of the cases affected has returned to the courts.[5]

In Rwanda, the priority after the civil war and genocide was also rebuilding social peace. Civil war crimes and genocide were treated differently from each other in transitional justice, partly due to the reluctance of the RPF to judge its crimes as a belligerent actor in the civil war, and also because of the prioritising of genocide prosecution.[6]

Rwanda's main challenge for transitional justice was the vast number of people that took part in the genocide. Despite other countries facing similar problems and opting for amnesties or selective prosecution, Rwanda chose the way of accountability through criminal trials. To achieve this, the government had to create community courts (Gacaca) to make accountability possible for low-level genocide suspects.

This choice of criminal prosecution was defended by the RPF as a measure to end impunity culture that led to the genocide. However, the massive prosecutions have ended up overwhelming the system and hindering the rule of law.

Legal framework and institutions

Constitution

In its transition to democracy, South Africa chose to completely re-write its constitution. The 1996 Constitution was promulgated by Nelson Mandela and entered into force in 1997, in place of the 1993 interim constitution. The interim constitution set the instructions for the final one, including universal adult suffrage, the prohibition of discrimination, multi-party democracy, separation of powers, etc.

However, the biggest achievement of the South African transition is how the institutions in charge of the elections have been built on consensus and with the guarantee of non-interference by the ruling party, making the Electoral Commission a body publicly perceived to be neutral and impartial.[7]

Rwanda held a referendum in 2003 to approve a new constitution, after a deep public consultation process. A new constitution was approved, prohibiting ethnic politics along with other forms of discrimination. This clause has been widely used by the government to maintain a one-party system by illegalising opposition parties and attacking any form of political dissent under the façade of preventing another genocide[8]. In 2015 term limits were abolished by referendum, allowing president Kagame to run for a third 7-year term.

Separation of powers and rule of law

In terms of separation of powers and checks and balances, South Africa ranks above the average of its region according to the world justice and rule of law index. Its overall score in the Rule of Law Index is of 0.59, making it the 45th country out of 128. The lowest rated indicators for the country are absence of corruption at 0.48 and criminal justice at 0.53. In terms of fundamental rights, all indicators are above average and above the upper-middle threshold except for no discrimination, valued at 0.54.

Constraints on government powers are measured at 0.63, and all indicators are above average and above the "upper-middle" threshold. Legislative and judiciary checks and balances are valued at 0.58 and 0.67 respectively, meaning that there is an effective separation of powers. However, and despite the absence of corruption ranking above average, in the legislative power is below the upper-middle threshold and valued at a worrying 0.23, and in the executive branch it is also below said threshold at 0.4. Corruption in the executive and the legislative powers can be explained as a consequence of the political dominance of the ANC and its firm grab onto power, and it should eventually fade away when a new party reaches power.

On the other hand, Rwanda is a fascinating case, since it presents a very low score on the democratic index[9] but an overall decent rule of law index. [10] In other words, Rwanda's government might not be democratic, but it does play by the rules, hence reinforcing the idea of an authoritarian social contract that is indeed being fulfilled by the government. In fact, despite being an authoritarian country, Rwanda's rule of law index is higher than South Africa's, and the second highest in Sub-Saharan Africa, only bettered by Namibia (one of the best-ranked democracies in the region).

To further prove the point of the authoritarian social contract, looking at the different indicators of the Rule of Law Index, one can notice that its lowest-rated indicators are the fundamental rights ones (0.51, ranking 81st in the world) and it's best indicator is order and security (0.84, ranking 22nd in the world) with a perfect score in absence of civil conflict (1.00).

Limits to governmental power by the legislative and judiciary powers are worth mentioning too. In the case of legislative checks and balances, the country ranks below the Sub-Saharan average, partly due to the predominance of RPF parliamentarians dominating the legislature. Hence they provide little checks on the executive. On the other hand, Judiciary checks and sanctions for official misconduct are above the Sub-Saharan average, showing a surprising level of judiciary independence for a country deemed as authoritarian.

Transparency and accountability

Transparency indicators show South Africa leading the regional chart, well above the Sub-Saharan average and also above the upper-middle threshold, which means that the government can be considered transparent enough. In the other hand, persistent levels of corruption in the executive and legislative power, as well as in the police and military (ranked above regional average but below the upper-middle threshold) show worrying signs that could obstruct the accountability of those holding power. Indeed, sanctions for official misconduct are the weaker link in constraints on government power, showing a limited action taken against corruption, but still ranking above the Sub-Saharan average.

In Rwanda, judiciary independence and sanctions for official misconduct are also above average for the region, showing an acceptable degree of accountability in the exercise of power that yet again can be surprising in an authoritarian country.

In terms of transparency, Rwanda ranks above the Sub-Saharan average in all indicators: publicized laws and government data (0.60), right to information (0.61), civic participation (0.53) and complaint mechanisms (0.60). Corruption indicators are above regional average as well with corruption in the legislative power being the worst of the lot despite still being better than that of its neighbouring counterparts.

Civil society

The ANC has, in a similar fashion to the RPF, tried to become a gatekeeping power, attempting to draw the limits of what is acceptable opposition or an acceptable discourse. This allows the parties to monopolize the social cohesion discourse by presenting themselves as the only legitimate actor to tackle the issue.

In South Africa, the ANC accuses the opposition parties of trying to bring back apartheid; for instance, it claims that the Democratic Alliance aims to return to a minority rule system. Thus, the party presents itself as the only one that can prevent the Boers from returning to power. A state of constant alert is promoted by the ANC, not only within national politics and against civil society actors, but also claiming that foreign agendas are seeking a regime change in the country and trying to turn the people against their leaders.[11]

In Rwanda, the government took advantage of the post-conflict situation to limit public participation in the political sphere. Those opposed to the government are marginalised and their discourse is rejected as genocide-promoting or supportive of ethnical divisions. This is key for the government to retain popular support, as any dissenting voice will be delegitimized and presented as a call to go back to the worst moments of Rwanda's history, and thus publicly rejected. As for dealing with foreign civil society actors, Kagame tends to delegitimize them by associating any dissenting foreign opinion with colonialism. [12] This overall helps the RPF sustain their rhetoric of the Rwandicity of the people as the only way of keeping social peace and cohesion.

This discourse that attempts to create national unity as well as within the parties, has a constant "rally around the flag" effect, silencing dissenting opinions and deterring potential civil society actors, in fear of being singled out as apartheid or genocide promoters. This results in a weakened civil society often deterred from criticising the government in fear of being marginalised and portrayed as either a colonialist or a promoter of ethnic division and genocide. Dissenting voices are turned into enemies of the nation and used for an "us versus them" political discourse.

Despite this, non-governmental checks on the exercise of power in South Africa are valued at 0.71, well above the Sub-Saharan average as well as the upper-middle threshold. Freedom of expression has the same score and again and both above the regional average and nearly reaching the higher threshold.

Overall, South Africa has a robust civil society that plays a key role in creating and sustaining political culture, tackling the gaps between national and local politics, as well as holding public officials accountable and checking their use of power. This can be seen in the outing of former presidents Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma through consistent mobilisations and lawsuits.[13]

For Rwanda, as expected in an authoritarian country, civil society is not a key actor. Non-governmental checks to the use of power are low (0.45), and likely limited by an also low freedom of expression indicator (0.45).

Conclusions

Treating democracy and non-democracy as a dichotomy instead of the two sides of a wide spectrum would not allow us to look at how different variables are key to understanding national politics. Instead, it is crucial to understand that many countries occupy a liminal space between democracy and non-democracy without necessarily moving towards either. Therefore, it is in that space that they should be analysed in order to be fully understood. That being said, South Africa and Rwanda both occupy very different liminal spaces, with the first being much closer to full democracy than the former.

The civil society indicators, as well as the role of transitional justice, show a very clear difference between South Africa and Rwanda, which is rooted in the legitimation of the power of the ruling party, as well as in the background of their political changes. The RPF came to power by winning the civil war and used transitional justice to whitewash its image as no RPF member has been investigated for alleged war crimes[14]. Thus, the lack of accountability and the militaristic nature of the transition can be seen as factors that discourage citizen participation in politics. On the other hand, South Africa had an easier task with transitional justice, but the result cannot be considered perfect or ideal, and many criticise the South African model of transitional justice for being too superficial and symbolic and not providing the needed social healing. Also, South Africa's transition is built on political consensus instead of the outcome of a civil war, and that spirit of consensus can be seen in the much bigger role of civil society nowadays. The ability of civil society actors to hold political ones to a high enough standard is key in rebuilding a country.

The transparency indicators show that both countries have open and transparent governments, with Rwanda scoring better than South Africa in the publicized laws & government data as well as the right to information indicators, which can be surprising due to the authoritarian nature of the Rwandan government.

Although both countries seem to be in very different positions, they share a political discourse based on party exceptionalism and rejection of dissenting voices as encouragers of genocide or apartheid. The fear of ethnic conflict is the very basis of the traces of an authoritarian social contract that still prevails in the South African and Rwandan politics.

In terms of institutional transformation, South Africa shows how important it is to build trustworthy institutions, with the best example being the Electoral Commission. Also, political trust in pacific transitions of power after an election is a sign of a consolidated democracy and shows the success of South Africa.

The level of transparency of the Rwandan government, added to its success in the accountability and security aspects and the high civil and criminal justice indicators (all above regional average) show how an authoritarian country can effectively deal with a post-conflict situation without abandoning its non-democratic model. Rwanda is a fascinating example of a successfully fulfilled authoritarian social contract in which civil liberties are given up in exchange for a peaceful and stable environment in which the country can heal economically as the quite positive GDP per capita projections show.[15]

[1] The Economist Intelligence Unit; Democracy Index (2019) https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index?&zid=democracyindex2019&utm_source=blog&utm_medium=blog&utm_name=democracyindex2019&utm_term=democracyindex2019&utm_content=top_link

[2] Beresford, A. Liberation movements and stalled democratic transitions: reproducing power in Rwanda and South Africa through productive liminality. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13510347.2018.1461209

[3] Huntington, S. P. (1991). The third wave: Democratization in the late 20th century.

[4] The Economist Intelligence Unit; Democracy Index (2019) https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index?&zid=democracyindex2019&utm_source=blog&utm_medium=blog&utm_name=democracyindex2019&utm_term=democracyindex2019&utm_content=top_link

[5] International Center for Transitional Justice, South Africa https://www.ictj.org/our-work/regions-and-countries/south-africa

[6] Waldorf, L, Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Rwanda, International Center for Transitional Justice https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-DDR-Rwanda-CaseStudy-2009-English.pdf

[7] Ahere, J. R. (2020). Africa's dalliance with democracy, but whose democracy? In N. Sempijja, & K. Molope, Africa rising? Navigating the nexus between rhetoric and emerging reality (pp. 37-54). Pamplona: Eunsa.

[8] Roth, K. The power of horror in Rwanda, https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/04/11/power-horror-rwanda

[9] The Economist Intelligence Unit; Democracy Index (2019) https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index?&zid=democracyindex2019&utm_source=blog&utm_medium=blog&utm_name=democracyindex2019&utm_term=democracyindex2019&utm_content=top_link

[10] World Justice Project, Rule of Law Index 2020 https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/research-and-data/wjp-rule-law-index-2020

[11] Beresford, A. Liberation movements and stalled democratic transitions: reproducing power in Rwanda and South Africa through productive liminality https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13510347.2018.1461209

[12] Beresford, A. Liberation movements and stalled democratic transitions: reproducing power in Rwanda and South Africa through productive liminality. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13510347.2018.1461209

[13] Gumede, W. How civil society has strengthened South Africa' s democracy https://www.corruptionwatch.org.za/civil-society-strengthened-democracy-south-africa/#toggle-id-1

[14] Waldorf, L, Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Rwanda, International Center for Transitional Justice https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-DDR-Rwanda-CaseStudy-2009-English.pdf

[15] IMF. "Rwanda: Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in current prices from 1985 to 2025 (in U.S. dollars)." Chart. October 12, 2020. Statista. Accessed January 25, 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/452130/gross-domestic-product-gdp-per-capita-in-rwanda/

The low voter turnout did not lead to questioning the re-election of Rebelo de Sousa, but it helped the far-right candidate to get a distant third place.

President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa during a statement to the nation, in January 2021 [Portuguese Presidency].

ANALYSIS / Elena López-Dóriga

Last Sunday 24th of January of 2021 Portugal held presidential elections despite of the country being in lockdown due to the advance of the Covid-19 pandemic. The President of the Republic Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa was re-elected, winning another five-year term after a campaign fought amid one of the world's worst outbreaks of coronavirus. The re-elected president won with a majority of 60.7% of the votes, therefore, with no need to go for a second round. It was already certain that he was going to win this election as he was already known as the favorite candidate in the polls. Nevertheless, the triggering questions for this election relied in how much the turnout could be affected due to the critical situation of coronavirus that Portugal was facing in the middle of a lockdown, and how much relevance was the new far-right wing party Chega was going to achieve, as it had been attaining a lot of popularity since its creation in the last April 2019. The elections were marked indeed by the historic absence of almost 61% (the electoral turnout was 39.24% of the registered voters), and the third position in the ranking of André Ventura, the leader of Chega.