In the picture

Collage with a dragon from Chinese mythology [CLI].

The great dynamism of the trade development between China and Latin America and the Caribbean since the beginning of the 21st century has been considered a natural extension of the well-known "Silk Road and Belt". However, recent manifestations of a certain trade imbalance and irrationally structured investment have jeopardized the sustainability of bilateral exports.

As Latin American trade with China completes two decades of great development, it is worth taking stock of the benefits, or harm, if any, that this trade has brought to the region exchange. This is what the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has done in its annual report on international trade. report annual report on international trade, which devotes a chapter to this timely assessment.

As important as the need to expand trade flows and investment injections is the need to modify the structure of the bilateral exchange . The reprimarization of exports entails notorious internal deficiencies (structural fragilities, trade dependencies and lack of industrial competitiveness) that cause great vulnerability to any international economic cycle that leads to a reduction in commodity prices. At the same time, a close look at current geopolitical and economic trends makes it possible to identify a possible relocation of value added in regional exports to China, while renewing the interest of some countries in signing specific trade agreements with China (in the context of growing trade tensions between world powers, disturbed by the consequences of the war in Ukraine and Palestine).

Economic and trade relations between China and LAC have made progress in the last two decades, B . In 2000, the bilateral exchange barely exceeded US$14 billion. However, two decades later, in 2022 it registered a figure of approximately 500 billion dollars, thus multiplying its value 35 times in that time. As of today, China has displaced the European Union as the region's second largest trader partner , absorbing 13% of exports and providing 22% of regional imports. The United States continues to hold shares of approximately 40% of exports and 30% of imports, thus securing its first place; however, several countries, especially in South America, have China as their first trading partner .

Being the region a source of material and energy resources necessary for China's intended global expansion, there are certain challenges that, far from negating the prominent trade relationship, question its sustainability and future. The region itself faces a difficult internal status situation, marked by different economic challenges related to recent inflation, uncertainty and some economic-structural imbalance. At the same time, China's expansive capitalism in places such as Latin America and the Caribbean entails serious impacts of environmental pollution in the extraction of raw materials or a significant impact on labor conditions and the environment of some indigenous peoples.

Undoubtedly, the main pending subject in subject of trade strategies in order to continue with the 2022-2024 joint action plan for cooperation between China and the region, consists of export diversification and sophistication. This was stated in the aforementioned ECLAC document.

Strategies to diversify and sophisticate exports vis-à-vis China are key to reducing vulnerability, promoting sustainable economic growth and improving a region's resilience in the face of changes in the global economic environment. However, this attempt to contribute to the development of a more dynamic and competitive regional Economics requires the identification and analysis of three determining elements that, in turn, will mark the future of the bilateral relationship: (1) the growth trend in the region's exports, (2) the trend towards greater reprimarization of exports, and (3) the diversity of South America's export patron saint compared to the patron saint registered in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean.

1. Export growth trend since 2000

Between 2000 and 2012, the value of the region's exports to China experienced a B growth, with an annual rate of 31.2%, tripling the 9.6% corresponding to the global export growth rate. During this period, average annual exports from South America to China increased from US$4.5 billion (in the three-year period 2000-2002) to almost US$84 billion (between 2010 and 2012), multiplying by a factor of 18. The same occurred with exports from Central America, whose value grew 18 times, from an annual average of just US$25 million (in the three-year period 2000-2002) to more than US$460 million (in the period 2010-2012). In the cases of Mexico and the Caribbean, average annual exports increased by a factor of 12 and 10, respectively, between the two periods. Thus, exports from all subregions and Mexico experienced double-digit annual growth fees between 2000 and 2012.

This period was marked by the so-called "commoditysuper-cycle ", on the back of a golden decade of rising commodity prices (especially oil and iron ore) and cheaper financing, both driven by an B expansion in Chinese demand. However, the expected continued growth in trade dependence and the dynamism of regional exports to China slowed significantly in the period between 2013 and 2022, as China's Economics moderated its pace of expansion, affecting commodity demand. Despite this, during this period, exports to China continued to grow at a much higher rate than the region's total exports, with fees annual growth rates of 6.4% and 2.3%, respectively.

China is projected to be the most dynamic and prominent export destination for the region in the coming years, even if it faces challenges related to environmental issues, structural dependencies or competitive problems for the region. Even if other areas such as the European Union reawaken their interest to regain the prominence they once had in the region, China will continue to grow as the most important driver of regional exports in the next decade.

Reprimarization of exports

One of the most interesting aspects to consider in Latin America and the Caribbean's trade relationship with China is the reprimarization of exports, a phenomenon that raises questions about the benefit or dependence of this trade relationship (considered by some to be a clear example of economic neocolonialism ). Between the 1960s and 1980s, many Latin American countries carried out industrialization processes through strategic import substitution. However, in the 1980s, various internal and external factors (the oil crises of 1973 and 1979, and the region's growing indebtedness) led to what is known as the "lost decade". During this period, these countries faced significant economic challenges.

In the 1990s, with the advent of liberal policies, industrial initiatives in Latin America cooled. Meanwhile, during the same period, China began to make massive investments to reshape the productive structure of its industrial sectors. Given its considerable expansion in the first decade of the new century (derived from its high investments), China not only expanded its trade relations with Latin America, but also increased its investments in the region, especially after the 2008 crisis. Under the slogan of a trade relationship based on mutual benefit, a considerable trade dependency was structured. While high exports of primary products to China were positive due to high demand and rising prices for these raw materials, high Chinese industrial investment eventually took over the competitiveness of the markets for more sophisticated products (i.e. products with higher technology). The decline of local industrial activity in Latin American countries dependent on the aforementioned "reprimarization of exports" entails a structural imbalance for the correct development of the region (linking its economic growth to periods characterized by booming commodity prices, and disabling any self-development that does not rest on structural dependence on foreign industries capitalized by Chinese investment).

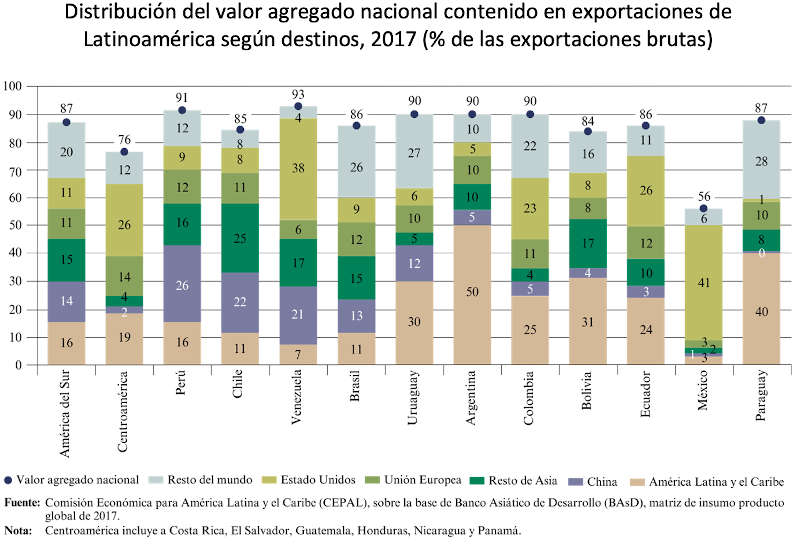

Exports of primary goods experienced the highest growth between 2000 and 2022, reaching at the end of this period outstanding shares of 83% in South America, 68% in Central America, 51% in Mexico and 46% in the Caribbean, as indicated by the ECLAC's report . In particular, in South America, the share of primary products in exports to China exceeded 90% in the three-year period 2020-2022 in countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador and Uruguay. On the other hand, exports from Mexico and Central America have a higher content of technology-intensive products, especially technology-intensive manufactures leave and average.

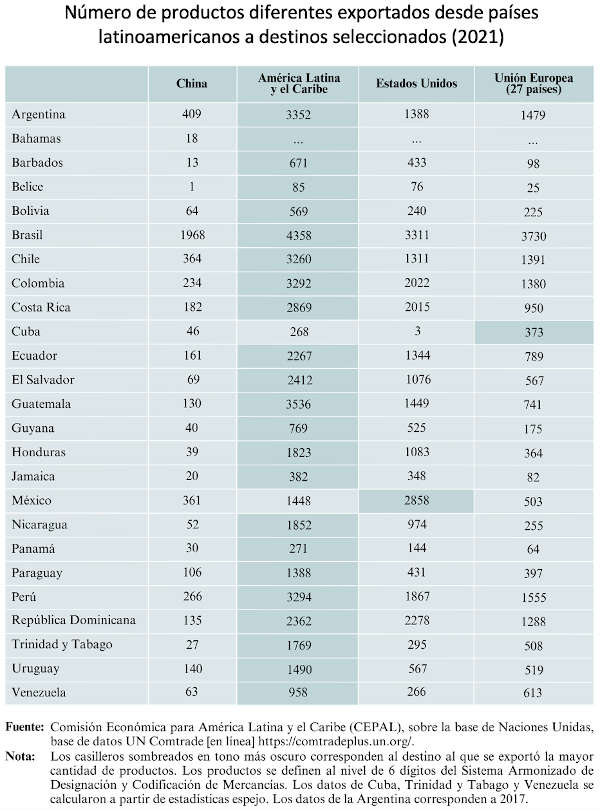

Regional exports to China show a B Degree concentration in a limited set of products. In the period between 2020 and 2022, just five products (soybeans, copper and iron ores, oil and copper cathodes) accounted for 67% of total exports to that country. Moreover, a list of 20 main products alone already accounts for 86% of the region's total exports. This high concentration of shipments becomes more evident when comparing the issue of products exported intra-regionally, or even to the United States or the European Union.