In the picture

Celebration of the fifth anniversary of the creation of the DFC, with an address by Antony Blinken, Secretary of State [DFC].

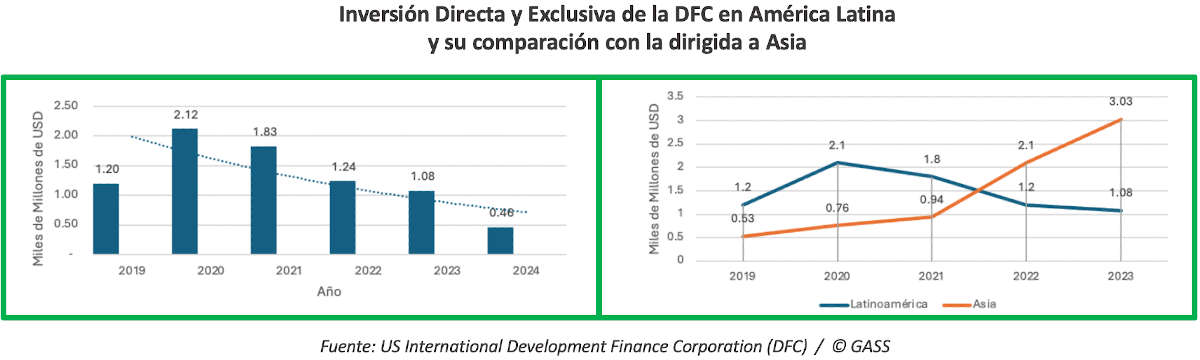

In an attempt to counter the influence exerted by China in the world through its credits and its Belt and Road Initiative, the United States reshaped its own public financing instrument abroad with the creation in 2019 of the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). Although the endowment of this agency has been increasing, this has not been the case for programs destined for Latin America, a region to which the US government has dedicated in 2024 a quarter of what it invested a decade ago, in contrast to the increase in allocations for other regions, such as Asia. Despite its rhetoric, the United States has not yet devised a coherent and lasting strategy to rival China's growing influence in much of its own hemisphere.

"We want to make sure that our closest neighbors know that they have a real choice between debt trap diplomacy and transparent, high-quality approaches to infrastructure and development," declared President Joe Biden in November 2023, at the Alliance for Economic Prosperity in the Americas (APEA) Leaders' Summit. Biden's statement showed U.S. discomfort with China's activity in Latin America and evidenced the growing geopolitical skill in the region. However, despite the rhetoric, the reality is that for regional leaders who see the United States as a potential ally and accelerator of their economic growth, the new initiative fell short. The absence of U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai from the summit reinforced the usual sense that Washington is not interested in making a competitive bid in Latin America, preferring instead to take care of business and obligations far from its neighborhood.

This perception is not entirely true, as it should not be forgotten that the United States is the country with the largest investment in Latin America, manager of one third of the foreign direct investment (FDI) received in the region. In 2023, 33% of the FDI that reached Latin American countries originated in the US, down from 42% in 2021 and 39% in 2022, but equally important, as indicated by the latest report ECLAC report. From agreement with the usual line, in 2023 the second individual investor was Spain, with 11% (from the EU as a whole came 22%). China, the source of only 4% of the FDI received by the region in 2021 and 3% in 2022, substantially restricted this already reduced activity in 2023, with imperceptible amounts.

But the FDI figure is misleading when it comes to assessing the 'political' influence that the great powers can exert. Unlike the United States, whose foreign investment is basically due to private initiative while public funds have been concentrated on aid to development to poor countries, China has turned to granting state loans to governments around the world, in a first phase (120 billion dollars to Latin American governments since 2005), and now, in a second phase, to financially endowing its companies to take a position in the various national markets. There is also the commercial chapter: China has become the first commercial partner of important economies, such as Brazil and Chile, snatching that place from the United States. In the space of twenty years, China has catapulted its influence in Latin America, with a strong presence in areas such as infrastructure, telecommunications and energy generation.

Investments in the leave

To reverse this status, Washington launched in 2019 the U.S. International development Finance Corporation(DFC ), created from a preceding agency. The U.S. Administration wanted to tailor this financial instrument to counter the global reach of the Belt and Road Initiative. The DFC presents itself as the counterpart that adheres to high standards of respect for the environment, human rights and workers' rights. While China uses its state financial muscle, the DFC builds partnerships with the private sector to finance solutions to the world's most critical challenges at development.

Since 2019, the DFC has promoted 117 projects for 15 countries in the region. The greatest beneficiaries of this capital have been Colombia, to which nearly $1.67 billion has been dedicated in 16 projects, followed by Brazil, with 11 projects and an income of $1.4 billion, and Ecuador, with $1.1 billion in 16 projects. The total budget earmarked for development in the Western Hemisphere between 2019 and 2023 amounted to $7.38 billion and could approach $8 billion cumulative by the end of 2024. The largest areas of approach are finance and insurance, technical scientific and professional services, as well as mining and agriculture.

Despite this, investment in Latin America has been declining over the last decade. At the beginning of the decade, the numbers reached US$2.12 billion, but in fiscal year 2023, they dropped to US$1.08 billion. By November 2024, the total was close to $500 million, predicting that the year would close with the lowest U.S. investment in a decade. This is not the case with Asian nations, where between 2019 and 2023 DFC investment reached $7.38 billion: although in the aggregate for those years this is a figure to that for Latin America, U.S. interest in Asia is on the rise. Since 2022, the DFC's investment in Asia has tripled the amount allocated to the Western Hemisphere.