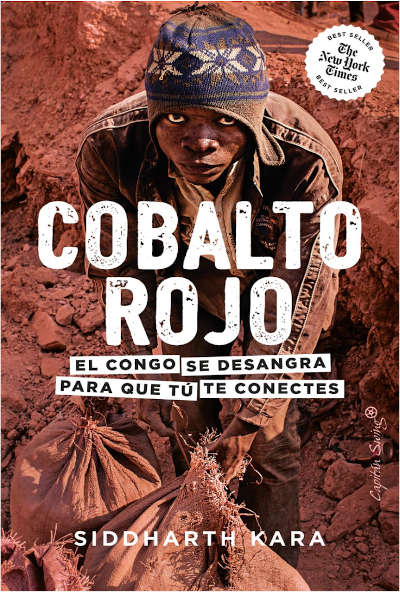

In the picture

Cover of Siddharth Kara's book 'Cobalto Rojo. El Congo se desangra se desangra para que tú te conectes' (Madrid: Capitán Swing, 2024) 304 pp.

For many of us, the first contact with reality that we feel at the very moment of regaining consciousness after sleep is the alarm that we have set on our mobile. We are all aware that, nowadays, the use of this device is almost essential in our daily lives. In addition to waking up, it is present in countless everyday actions as relevant as getting information, communicating with our loved ones, finding our way around a city, consulting endless information, listening to music, taking photographs and even paying in any store.

In addition to mobile, it would be difficult to recognize daily life in the first quarter of the 21st century without the use of devices such as laptops or tablets that are also powered by lithium batteries, not to mention the growing presence and presumable trend towards the use of electric vehicles also powered by batteries that require a thousand times more material than that of a cell phone. A key element in the composition of these lithium batteries is cobalt, a mineral that improves their size and performance. It is estimated that 75% of it is found in the subsoil of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In 'Red Cobalt. Congo Bleeds Out for You to Connect', writer and professor specializing in Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery Siddharth Kara offers a first-hand account of the human rights violations behind the mineral exploitation industry in the African country. Through an exhaustive research on the ground, Kara documents the harrowing conditions of work of those engaged in mineral extraction, as well as the abusive practices in the supply chain that runs from the mine to our devices.

Cobalt is a mineral that is found relatively shallow underground, which means that it can be extracted without the need for a large investment in machinery and infrastructure, known under the euphemism of 'artisanal mining', i.e. mining using little more than picks and shovels. Ninety percent of the cobalt mined in Congo comes from artisanal mining with all that this entails in terms of worker safety. Kara documents the high frequency of accidents, including cave-ins, inside the tunnels. Cobalt fever and the widespread corruption of the authorities mean that not even the most basic safety measures are guaranteed in the mines.

At present, 85% of the cobalt mines are in the hands of Chinese companies due to the agreement signed between the government of former president Joseph Kabila and China whereby Beijing would be responsible for rebuilding Congolese infrastructure devastated by the successive wars that have ravaged the country in recent decades in exchange for mining concessions. Cobalt needs to be refined in order to be employee used in batteries. Thus, in 2021, 75% of the cobalt refined worldwide was produced in China.

The supply chain that begins at the mine is characterized by the presence of a series of intermediaries that makes it, in Kara's words, "a new chapter of slavery". Poverty and lack of opportunity mean that entire families live from day to day digging for ore through a system in which they sell the extracted ore by weight in exchange for a tiny fraction of its final price to a series of middlemen who bundle it and deposit it in outlets controlled, in the vast majority, by Chinese nationals. Child exploitation and sexual violence against women are another element of the macabre landscape of the mines.

It is not the first time in Congo's history that its natural wealth has become its curse. The Spanish-Peruvian Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa describes in his work 'The Celtic Dream' the dynamics of abuses prevailing in the Congo during the colonial regime of King Leopold II of Belgium. On that occasion the goal was to feed the international rubber market, essential to manufacture tires at a time of automobile expansion. The novel also tells how the publication of the report prepared by the diplomat Roger Casement to publicize the status stirred the consciences of society. Today, people whose ancestors were forced to measure their lives in kilos of rubber during the regime of King Leopold II of Belgium now do so in kilos of cobalt.

Through this work one comes to wonder how the world has been able to advance in such a way that we can see and hear in real time a person on the other side of the world and, at the same time, our way of life is being kept running by a real human and environmental catastrophe. Time will tell if this work, magnificently crafted despite its harshness, constitutes a 21st century report Casement.