In the picture

Latin American Presidents at the CELAC summit in September 2021 [Gov. of Mexico].

"The authorisation of indefinite presidential re-election is contrary to the principles of a representative democracy and, therefore, to the obligations established in the American Convention and the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man". With this conclusion, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) has sought to mark a red line in the constitutional revisionism that is taking place in Latin America with regard to presidential re-election.

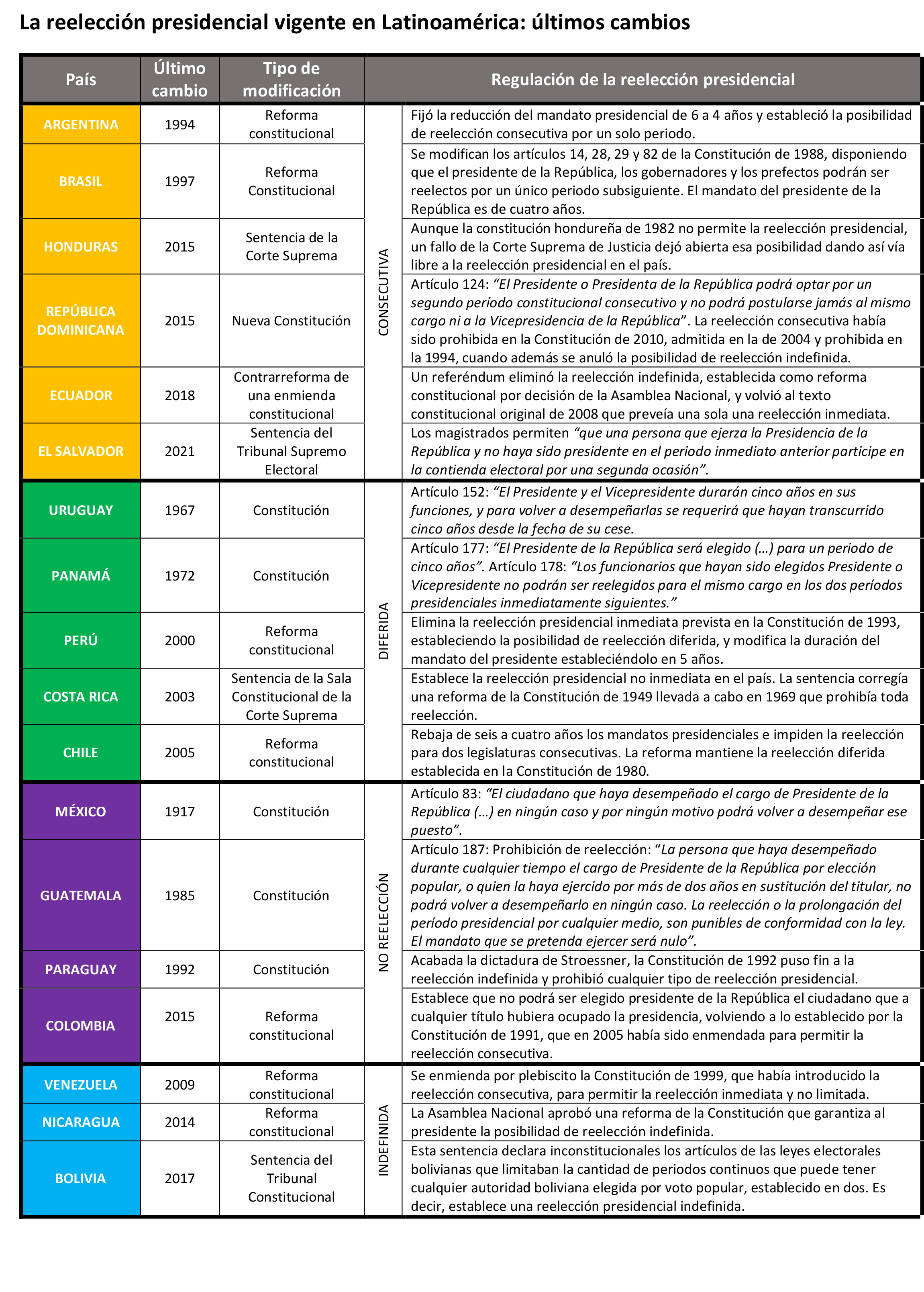

When in the early 1990s, in what Huntington called the third wave of democracy, most Latin American countries inaugurated their new democracies after a period of military dictatorships or civil wars, almost no national constitution allowed for consecutive re-election. Twelve of the 18 Latin American countries (excluding Cuba and Haiti) - that is, 67% of the constitutions - included only deferred presidential re-election (the possibility of returning to the presidency after one or two terms out of office), while 4 countries (22%) banned all subjectre-election; only in 2 cases (11%) was consecutive re-election for a second term allowed (after having started with a system that briefly accepted indefinite re-election).

These clear rules, which were intended to ensure the democratic health of Latin American presidential regimes - avoiding leverage of power by the top leaders and thus attempting to correct what in many cases had been a historical succession of caciques and oligarchs - have been eroded as the region has seen the emergence and consolidation of leaders with pretensions of permanence in the positionand, on occasions, authoritarian tendencies. If we compare the regulations that existed in 1990 with those we find in 2021, of the 18 Latin American countries, 8 have lowered the barriers to re-election: 5 have come to admit consecutive re-election and 3 others have come to accept indefinite re-election (Venezuela and Nicaragua persist in it and Bolivia has not formally reversed it; Ecuador came to admit it, but today only contemplates immediate re-election).

Latin America's democratic deterioration in recent years has gone hand in hand with this process of loosening limits on presidential re-election. It is debatable whether this is a cause-effect relationship; however, it is clear that presidents less inclined to accept the demands of accountability have sought the introduction of re-election in order to remain in power and that Latin America's illiberal democracies, in their developmentand consolidation, first introduced consecutive re-election as an intermediate step towards indefinite re-election.

The latter, in any case, seems to mark a dividing line in the Latin American presidentialist model, with Venezuela and Nicaragua as regimes commonly classified as authoritarian. This seems to be the understanding of the IACHR, which reached the aforementioned pronouncement after Colombia, pointing to Bolivia's status, carried out a enquiryon the figure of indefinite presidential re-election in the context of the Inter-American Human Rights System.

The origin of this enquirylies in Evo Morales' candidacy for a fourth presidential term in Bolivia in 2019. Despite the fact that the Bolivian Constitution promoted by Morales himself only introduced re-election for a second term and therefore prohibited going further, his party, the Movement Towards Socialism (Movimiento al Socialismo), won a ruling from the Constitutional Court that re-elections could be held indefinitely because, it argued, running for office is a "human right". Advisory Opinion 28/21 issued by the IACHR refutes the Bolivian Constitutional Court's interpretation of the Pact of San José and points out that it violates article23 of the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights. Furthermore, it argues that this prohibition seeks to prevent persons holding elected office from perpetuating themselves in the exercise of power.

The Court's August ruling, however, has not tempered some desires to move towards at least consecutive re-election. A month later, El Salvador's president, Nayib Bukele, put in place various legal mechanisms to enable him to run for re-election. In September, the Salvadoran Supreme Court, whose renewal was forced by Bukele himself in May, declared consecutive re-election legitimate, distorting the common interpretation of the constitutional text, which only admits it in a deferred manner. Moreover, through his vice-president, Bukele is promoting a constitutional reform that could endorse this change (he is also considering extending presidential terms from five to six years), something feasible thanks to the large majority that his party, Nuevas Ideas, has in the National Assembly.

Fujimori and Chávez, forerunners

Alberto Fujimori was the first to disrupt, in pursuit of re-election, the Latin American constitutional order with which the region began its new democratic era at the beginning of the 1990s: in 1993 he managed to be re-elected in Peru for a second term (and then a third in 1996, which barely lasted). Without mimicking Fujimori's authoritarian drift, other leaders also promoted re-election for a second term, such as Carlos Menem in Argentina (1994) and Fernando Henrique Cardoso in Brazil (1997), and other countries such as Uruguay and the Dominican Republic introduced some variations, with normal democratic respect. Some of the reforms also established a two-round presidential election system, the possibility ofimpeachment or a recall referendum, instruments that have not always been used correctly.

If Fujimori, from right-wing populism, opened the way for reforms that favoured an immediate second term, Hugo Chávez, from left-wing populism, opened the door to the introduction of the indefinite election that the region had known in the decades of authoritarianism.

diaryRe-election has been precisely one of the points core topicof Bolivarianism, as seen in Venezuela and Nicaragua, and also in Bolivia and Ecuador. The presidents of these countries first sought consecutive re-election, normally by making approvenew political constitutions that included this option and also allowed them to reset the re-election count to zero (Venezuela, 1999; Ecuador, 2008; Bolivia, 2009). Then, in a context of a loss of democratic quality due to the control they acquired over the other branches of government, they imposed indefinite re-election, either through a plebiscite reform of the recent constitution (Venezuela, 2009), or through a deviant interpretation by parliament (Nicaragua, 2014; Ecuador, 2018) or by a high court (Bolivia, 2017).

In these trials, these presidents claimed that the highest judicial bodies in their respective nations had allowed them to run for re-election after careful interpretation of the constitution and the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights. However, these are countries that lack a judicial system independent of the executive, so these decisions often have partisan overtones that benefit the person in power at the time.

In the midst of what in the last decade could be described as "fever" for re-election - which has known some turbulent episodes such as in Honduras or, without being approved, in Paraguay, a country that persists in non-reelection (established with the 1992 Constitution that closed the Stroessner era) - there have been two notorious cases of a return to greater limits after having gone beyond them.

In the last twenty years, only two presidents have been re-elected in Colombia: Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010) and Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018). The 1991 Constitution prohibited any re-election (the previous constitutional text allowed for deferred re-election), but in 2004 Uribe introduced a reform to allow him to serve another consecutive term at position. Presidential re-election was only in force until 2015, when a constitutional amendment was approved that restored the ban on re-election. This desire to draw limits led the Colombian political classto reject in 2020 an proposalinitiative to at least lengthen the single presidential term from four to five years; the initiative, presented by political allies of President Iván Duque, although without his support, did not prosper.

As for Ecuador, in 2015 the National Assembly began the process to introduce indefinite re-election, with a back-door reform, without a referendum, of the Constitution, whose 2008 text had already established consecutive re-election and which now fell short of what Rafael Correa needed to remain in power. Correa made approvethe change, thanks to the absolute majority he had in the legislature, but social unrest led him to finally cede the post of candidateto Lenín Moreno. As the new president and distanced from his mentor, Moreno included the question of re-election in a referendum in 2018. The "no" to indefinite re-election, returning to consecutive re-election for a second term (which Moreno later declined to run for), won with 67.5 per cent of the vote, thus spelling the end of "Correism".

Bolivia, meanwhile, is in a certain regulatory limbo. Morales had to leave power due to military and social pressure over a 2019 re-election that the international community pointed to as fraudulent, but the Constitutional Court that in 2017 allowed indefinite re-election has not reversed that ruling, despite the recent ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

Towards a new political paradigm

A comparison of this succession of regulations with those that existed in Latin America in the early 1990s, when most of the region was in the early days of its democratic systems, shows a reduction in the safeguards that were then in place to prevent excessive presidential power.

In 2021, consecutive re-election for a second term is approved in 6 countries (Argentina, Brazil, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras and Honduras); deferred re-election is applied in another 5 (Chile, Costa Rica, Panama, Peru and Uruguay); non-reelection is maintained in 4 (Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico, Paraguay), and indefinite re-election is in force in 3 (Bolivia, Nicaragua and Venezuela).

Although three decades ago re-election was possible in the region, it was mostly reserved for deferred approaches (it occurred in 12 of the 18 countries), conceived precisely as a way of avoiding excessively dominant presidentialisms. Current figures point to a shift towards consecutive and indefinite re-election, which could lead to the emergence of a new political paradigm result. This phenomenon may lead to a "hyper-presidential" system in which there is no effective division of powers.

This phenomenon is consistent with the patrimonialist conception of power that exists in Latin American politics, something that is independent of the ideology of the ruler. As Adolfo Garcé García y Santos points out in Raíces y consecuencias de la hegemonía presidencial en Iberoamérica, "Ibero-America has been more successful in building dynamic economies than in establishing stable democratic institutions". In his opinion, "the region became independent from Spain and Portugal before it was able to develop good answers to the question of how to balance order and freedom. The presidentialist modelwas adopted. But the president was endowed with the powers that characterised monarchs'. This fact has given rise to what the author calls "the endemic fragility of Ibero-American democracy".

This characteristic of Latin America's political system contributes to the region's relatively weak rule of law. Most re-election efforts have been led by charismatic presidents who promise to address urgent demands; once re-elected, they significantly increase their powers and deviate from the mandates of democratic constitutionalism.

Beyond the reasons that lead to the new paradigm, some programs of studypoint to the negative impact that the reduction of safeguards on the possible re-election of presidents is having on Latin America's democratic health. Michael Penfold, Javier Corrales and Gonzalo Hernández warn that the region 'seems to have made an irreversible break with one of the most important legacies that marked its democratic transition processes: the prohibition of consecutive re-election schemes in order to promotea greater alternation of power and thus reduce political conflicts around the presidency'.

These authors concede that in theory consecutive re-election is not necessarily negative for the functioning of democracy, and cite the view of those who argue that limiting re-election is undemocratic and does not financial aidimprove accountability. instructionsHowever, they note that the Latin American reality samplethat "those presidents who have attempted to reform their constitutions to allow for re-election beyond one additional term have tended to undermine the rule of law and the division of powers". "In no country in the region has there been a democratic consolidation anchored on consecutive re-election schemes for the executive branch", they conclude.

The study also notes that "the deferred system performs better on the functioning of the rule of law, levels of corruption, political stability and government effectiveness". In fact, the three countries that usually obtain the best scores in the rankings on democratic quality and institutionality carried out by different organisations - Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay - restrict re-election to non-consecutive terms. The authors do not directly establish a causal relationship, but the statistical reality is suggestive (however, Haiti, which we have not included in the computations of this analysis, has deferred re-election, which is planned to be maintained in the new Constitution pending approval).

A greater causal relationship, however, in line with the IACHR's assessment cited at the beginning of this analysis, can be seen in relation to the democratic degradation that, in a presidentialist system, leads to the permanence of the same person in power for more than two terms. According to Penfold, Corrales and Hernández's research, countries with undefined systems "perform poorly in terms of institutional quality". "These results", they say, "can perhaps be explained by a gradual institutional destruction, propitiated by the strong presidentialist and personalist character that prevails under this system subject".

End of the era of the "democratisation wave".

In her articleThe Rule of Law in Latin America: from Constitutionalism to Political Uncertainty, Catalina Botero includes a quotationby political scientist Samuel Huntington, who states that democratising waves are followed by a democratic decline that puts the gains achieved at test. According to the table above, and taking into account the current statusin some of the countries discussed here, everything suggests that we are at the beginning of this democratic decline.

In the wake of the travesty of elections in Nicaragua on 7 November, which led to the re-election of Daniel Ortega for the fourth consecutive time, there has even been talk of the end in Latin America of the era of the third "democratising wave" that Huntington spoke of when the USSR disappeared. Democracies spread in Latin America in 1990 after decades of dictatorships, guerrilla warfare and civil wars, and Nicaragua is a symbol: that year Ortega lost absolute power when the revolutionary FSLN regime fell, now he has regained it completely.