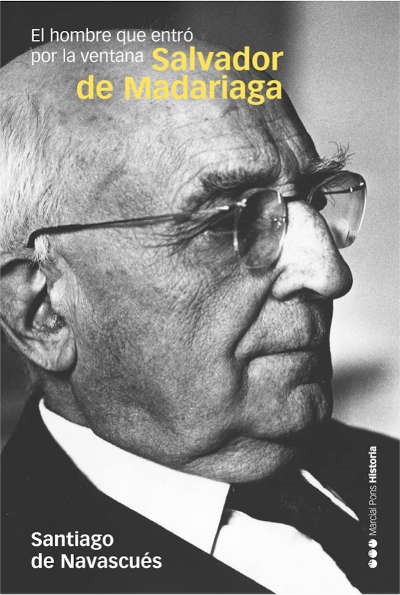

In the picture

Cover of the book by Santiago de Navascués 'Salvador de Madariaga. El hombre que entró por la ventana' (Madrid: Marcial Pons, 2023) 347 pages.

Forty-four years after his death in Locarno, Switzerland, Salvador de Madariaga remains a perfect stranger to most Spaniards. This is in spite of his enormous intellectual stature; of his enormous and important literary production, part of which has not yet been translated into his mother tongue language ; of his multifaceted character; of the wide international recognition he received during his lifetime -as so often happens among Spaniards, he is more appreciated abroad than in his own country, where he is ignored, if not vilified; Or of his conciliatory disposition, which so well embodies the spirit that ran through Spain at the end of the seventies of the last century, and which now so urgently needs to be rescued from the polarization that grips the country.

Salvador de Madariaga. El hombre que entró por la ventana' (The man who came through the window) has been published with the aim of spreading the life and work of this universal Galician who dreamed of a Spain different from the one he had to live in: a tormented nation that led its children to a bloody civil war and long years of disagreement whose end the thinker thought he glimpsed before his death in 1978.

The work, thesis doctoral of the young historian Santiago de Navascués, would already be a contribution B to the historiography of contemporary Spain just for offering what is probably the best portrait of this multifaceted character who, surprisingly, had not been biographed in such a complete way until now.

The merit of the author, however, is not limited to this because, in addition to this, he makes a rigorous and dispassionate study, based on the deep analysis of multiple primary sources related to the character, in a conscientious reading of his work, and in an exhaustive knowledge of the historical context in which Madariaga lived and worked. And he does it, moreover, with a display of literary style B. The mastery of Spanish that he exhibits throughout the work, which can only be the result of years of sowing in an environment of love for reading and study, is A, as are the richness and precision of the vocabulary he uses, or the narrative vividness with which he weaves an accessible and very pleasant text that captures all the nuances of the personality of the protagonist and the evolution of his political positions.

The Madariaga who offers us this work is a character difficult to classify. Engineer of training, he dedicated his life to literature, to the academic world, and to journalism, but, above all, to the International Office, devoted to the causes of internationalism and international cooperation and peace from the different positions he held in the League of Nations, of whose Disarmament Section he became the maximum manager or, also abroad, in the service of a Second Republic that, like many others, ended up disappointing him deeply.

A man of an open and conciliatory disposition, Madariaga cultivated friendships with people of different political affiliations and as different from each other as Ramiro de Maeztu, Fernando de los Ríos or Julián Besteiro. His character, together with his somewhat heterodox liberal affiliation -which led him to define himself as a 'heretical liberal'-, earned him a great deal of misunderstandings, criticism and even enmity from both sides of the political spectrum. Well known in this sense are, for example, the controversies he had with intellectuals such as Ortega y Gasset -who, in a manner as well known as incisive, defined the Galician as a "fool in five languages"- or Claudio Sánchez Albornoz.

Convinced of the value of international cooperation; a staunch defender of the League of Nations and internationalism, even against the sign of the times -which earned him nicknames such as 'Don Quixote of Manchuria' or 'conscience of the League of Nations'-; apostle of international liberalism; tireless promoter of the idea of European federalism; radical anticommunist; staunch anti-Francoist, largely due to the inquina staff he felt for a Generalissimo who plundered his Spanish properties, Madariaga was always a contradictory man who, without being a Christian, saw Christianity as a guarantor of freedom, and Christ himself, together with Socrates, as the foundation of the European spirit; or who faced accusations of proximity or, even, collaborationism with General Franco's regime when he advocated the idea of 'organic' democracy which he was so close to the National Movement. However, in the midst of all these ups and downs, liberalism constantly appears as a 'leitmotiv' in Madariaga's biography, even when his mundialism cools down or when, in the last part of his life, he moves towards more conservative positions.

With the strength and solidity of his exhibition, Santiago de Navascués makes it clear that, independently of the judgment staff that his political or vital postulates deserve, Salvador de Madariaga has been one of the characters that have shone at the highest intellectual level in Spain in the 20th century. To rescue his figure from oblivion is a meritorious task in which this good historian, to whose evolution and future production it will be convenient to pay attention.