In the picture

visit of Evo Morales to the Silala riverbed when he was Bolivian president [Pres. of Bolivia].

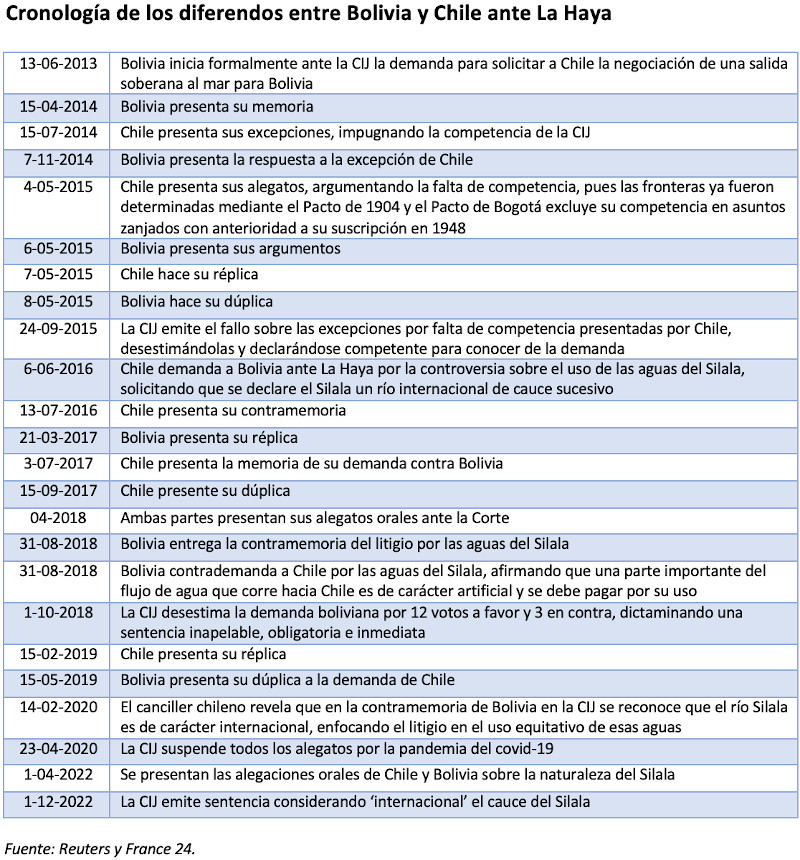

In the December 1 ruling of the International Court of Justice in The Hague on the dispute between Bolivia and Chile over the use of the waters of the small Silala River, the Chileans achieved more than their neighbors. The high court of the United Nations grants "international" - therefore, shared - character to a river that Bolivia wanted to reduce to a simple spring, whose management intended to carry out without taking into account the rights of the country downstream. But the Chileans may see the flow reduced, since the Court admits that some of the channels that increase the flow are "artificial", made at the time on Bolivian soil by a Chilean business . This sentence, which was to close one of the controversies derived from Bolivia's loss of access to the sea in the 19th century, once again leaves the two countries in a status of possible friction, if not for the sovereignty and character of the riverbed, then for the management of its waters.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) did not actually have to make any decision, as the two countries finally agreed on agreement. In 2016 Chile sued Bolivia after President Evo Morales accused its neighbors of "stealing" and "diverting" the Silala, a watercourse that rises in Bolivia's Potosí and, after a dozen kilometers, its waters feed several tributaries of the Loa, Chile's main river. Although its flow is small, it is an important water resource as it flows through the Atacama Desert and provides water to department of Antofagasta, headquarters of the large Chilean copper industry. Bolivia counterclaimed in 2018, claiming that Chile should pay, even retroactively, for the use of the water.

Once the sentence was published, the president of Chile, Gabriel Boric, considered that his country had seen all its claims recognized and that it was Bolivia who had been moving positions to overcome the dispute. For his part, Bolivian President Luis Arce, on the other hand, emphasized that, although the Silala is an "international" course, the ICJ recognizes Bolivia's sovereignty over the existing "artificial" channels and leaves the future of these in the hands of the Bolivian authorities. The Government of La Paz indicated that the canalizations increase the flow between 11% and 33%, subtracting it from a possible contribution to the wetlands, but announced that it will not take any decision on the matter immediately. In any case, the Court established that Chile should not pay for the benefit of the reinforced Silala channel.

Origin of the dispute

This conflict between Chile and Bolivia dates back to the War of the Pacific (1879-1884), in which Chile faced an alliance between Bolivia and Peru. On February 14, 1879, Bolivia increased taxes on the Chilean-British business Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta, which the Chileans saw as a violation of an 1874 treaty. Faced with Bolivia's refusal to accept arbitration, Chile invaded Antofagasta. With Peru withdrawn from the war, the defeat led Bolivia to sign the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Commerce with Chile in 1904, which set the limits between the two countries. As result, Bolivia lost its Pacific coast, including the port city of Antofagasta, which belonged to Chile. In addition, it was established that the waters of the Silala were international and concessions were made by both countries for the use of the river's water; however, this matter was later reopened due to the lack of agreement on the use and sovereignty of the water resource .

An essential condition of the Peace Treaty was the construction by the Chilean state of a railroad from Arica to La Paz. However, a railroad from Uyuni, in the Bolivian highlands, to Antofagasta was also built by private initiative, at position of the business The Antofagasta-Bolivia Railway Company Ltd. (later named Ferrocarriles Antofagasta-Bolivia). For the steam train used on this second route, a large amount of water was necessary, for which the prefect of department of Potosí granted the aforementioned business the licence of the waters of the Silala, recognizing it as an international river. In 1910 a public deed was granted authorizing the construction of canals and masonry works in Bolivian territory and the use of the waters of the Silala River at no cost. In 1962 the steam train ceased to be operational and, therefore, the purpose of the concession disappeared, as the need to use the waters of the Silala by the business was eliminated.

However, it was not until 1996 that the Bolivian Government began to reject the concession made by Chile in 1906 to the British business Ferrocarril de Antofagasta a Bolivia (FCAB), finally revoking the concession in 1997, arguing that business had not respected the agreements. In 1997 the Bolivian Chamber of Deputies ordered the elimination of the term "river" to refer to the Silala, considering it a spring, and considered charging Chile for its use. In 1999, the Bolivian government declared that the Silala River belonged exclusively to its sovereignty, thus intensifying the dispute between the two countries. In addition, in 2002 Chile diverted the course of the river in its territory for its own benefit.

Therefore, in 2009, the presidents of Bolivia and Chile, in the framework of a rapprochement program or "diary of the 13 points", tried to reach a agreement, but this could not be achieved because the Bolivian Parliament did not accept the negotiated pre-agreement. The pre-agreement established that Chile should pay 50% of the waters of the Silala for the duration of the technical programs of study on its use and exploitation. However, Bolivia proposed after two years that the payment should be retroactive to the connection of the waters to Chile at the beginning of the 20th century, which Chile rejected. Finally, Bolivia opened a trout hatchery that is supplied from the Silala, even though it could affect the quality of the waters, to which Chile responded by declaring that the river was an area of international waters, which originates in Bolivia but continues in Chile.