In the picture

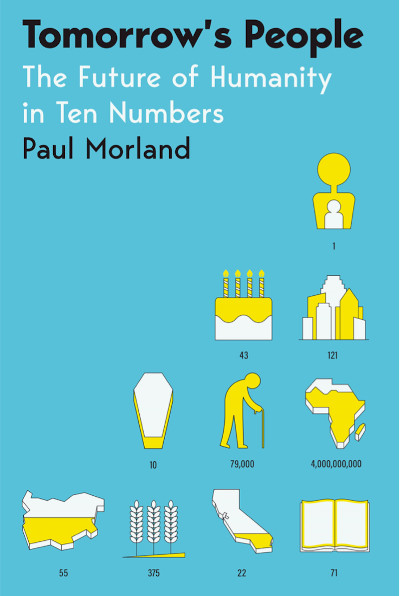

Cover of Paul Morland's book 'Tomorrow's People. The Future of Humanity in Ten Numbers' (London: Picador, 2022), 393 p.

The British demographer Paul Morland continues the success of his previous work, The Human Tide, with this new submission, which follows on from it. As the first one already dealt with the main demographic principles that explain the development of the world since, coinciding with the Industrial Revolution, nations began to experience sustained demographic explosions, in this second work Morland develops some aspects that were not sufficiently explained before due to space issues or that look more towards the present and the future. The text is structured around ten figures, taken from examples that illustrate the demographic dynamics on which the author wishes to insist.

One of them has to do with the increase in the age average of the people who make up our societies. To address this he takes the case of Catalonia and the 43 years of average that Catalans have today; from there he concludes that the chances of a social revolt that would violently force the independence of the region are slim: revolutions rather occur in countries with young populations. This may also apply to China: the Hong Kong protests of 2019-2021 were quelled without much effort on the part of Beijing; however, those that took place thirty years earlier in Tiananmen, with a larger youth cohort, capsized the regime.

"Not all young societies are prone to violence, but almost all violent societies are young," says Morland, leading him to predict a future decline in the gang phenomenon in Central America as the population ages. That rule does not properly affect organized crime violence, which revolves around specific, very lucrative businesses, so Mexico's aging population should not lead to a per se overcoming of drug-related crime.

Morland pays particular attention to the demographic future of Africa, the great question that will decide the fate of the world in the coming decades. He is not convinced that Africa will mimetically follow the process previously reproduced very precisely by other societies: first a demographic explosion, starting with the reduction of infant mortality, and then a demographic transition that increasingly reduces the fertility rate, falling below replacement level and leading to a progressive shrinkage of the population. Africa is already in the transition phase, but for cultural reasons many countries of the continent could maintain the fertility rate above replacement level. This is not a minor issue: it will determine whether 15 billion people will live in the world by 2100 or just over 7 billion.

Having started the process of demographic changes "gave Europeans the advantage of the first mover," colonizing a large part of the world and leading the international economic Structures , but "Africans will have the advantage of the last mover," warns the author. The ability of African countries "to absorb their billions of people into productive jobs and integrate them into the global Economics will define the fate of the world in the coming decades." Morland seems inclined to think that the migratory flow to Europe that we see today will not be of long duration and that as the century progresses the major mobility will be within the African continent itself.

It is a book aimed at the general public that, although it handles some technical concepts of a certain field of knowledge, it is easy to understand, because there is nothing more real than demographic evolution and its direct impact on today's issues and those of tomorrow.