In the picture

Fuel tanker of Petróleos Mexicanos, Mexico's state-owned oil company [Pemex].

Mexico passed an energy reform in 2013 that, with the end of Pemex's monopoly, opened up the oil sector to private and foreign initiative. The aim was to reverse the decline in crude oil production, as well as to obtain the financing and technology necessary to modernise the state-owned company. Opposed to this opening, which he describes as "betrayal of the homeland", Andrés Manuel López Obrador has been pushing for a reversal of this policy since he became president in 2018. At the end of 2021, he presented a counter-reform that, although it focuses more on the electricity sector, also has consequences for the oil sector. López Obrador's statism and an international situation that is more focused on renewables could dampen investor interest in Mexico.

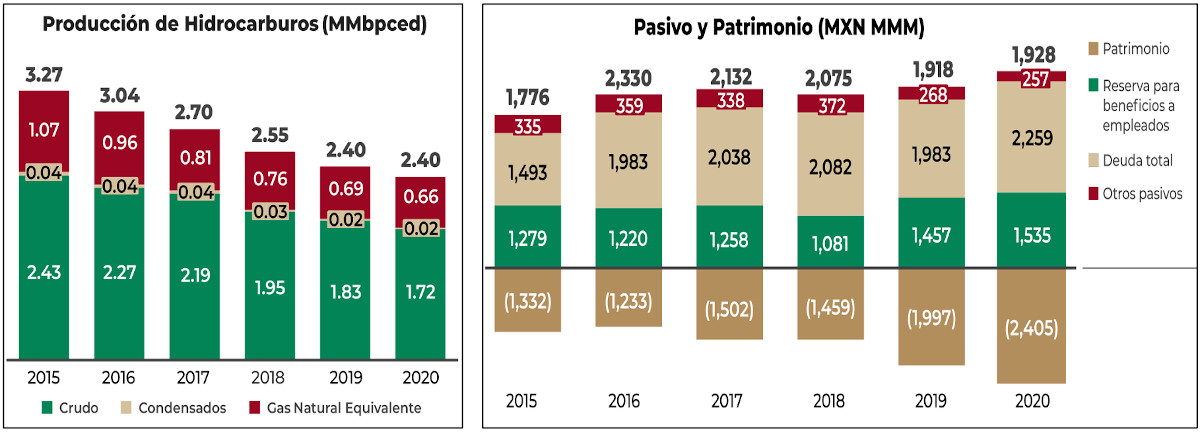

The 2013 'Pact for Mexico', which at the start of Enrique Peña Nieto's presidency brought about various reforms - approved at congress with the support of the then three major political parties (PRI, PAN and PRD) - endorsed the view that, without foreign investment, the Mexican oil sector could not prosper. Having reached a production peak of 3.4 million barrels per day in 2003, which contributed 33 per cent of the state's income, ten years later there was an "inevitable and inexorable decline", as the Wilson Center would later point out. Unless the state oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), obtained the necessary technologies and know-how through agreements with large private companies and foreign investment for new projects, Mexico would make little profit from its hydrocarbon reserves, many of which are in deep water or unconventional formations.

The desirability of opening up the oil industry had been clear for a long time, but in Mexico the idea of national sovereignty over all that is found in the subsoil has always weighed - politically and socially - as already enshrined in 1917 in the current Constitution (art. 27). Since 1938, when the government of Lázaro Cárdenas nationalised the oil industry and created Petróleos Mexicanos, the activities of extraction, processing and distribution of hydrocarbons have been the sole responsibility of this business . Given this 'patrimonialist' conception of the nation's natural resources, shared in many parts of Latin America, it is not surprising that Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his populist Morena party, now in the majority, are once again pushing for state control of the oil and electricity sectors (as far as possible, since there are legally binding agreements already signed with private companies, although the government is prepared in some cases to break them, especially in electricity generation).

The Mexican congress implemented the energy reform by amending the Constitution at the end of 2013 and passing the legislation implementing it in August 2014; the first rounds of new oil field awards for exploration and production took place from 2015 onwards. The Energy Reform Law opened up the possibility that the Mexican nation could award assignments and contracts for the exploitation and extraction of resources to private companies, both in partnership with Pemex and separately. The objectives of the reform, as stated in the executivesummary of project, included "attracting greater investment in the Mexican energy sector to boost the country's development " and "having a greater supply of energy at better prices". At the same time, oil production was expected to increase from 2.5 million barrels per day in 2013 to 3 million barrels per day by 2018 and 3.5 million by 2025, figures that have not been achieved (in 2020, production was 1.7 million barrels per day).

Bad timing

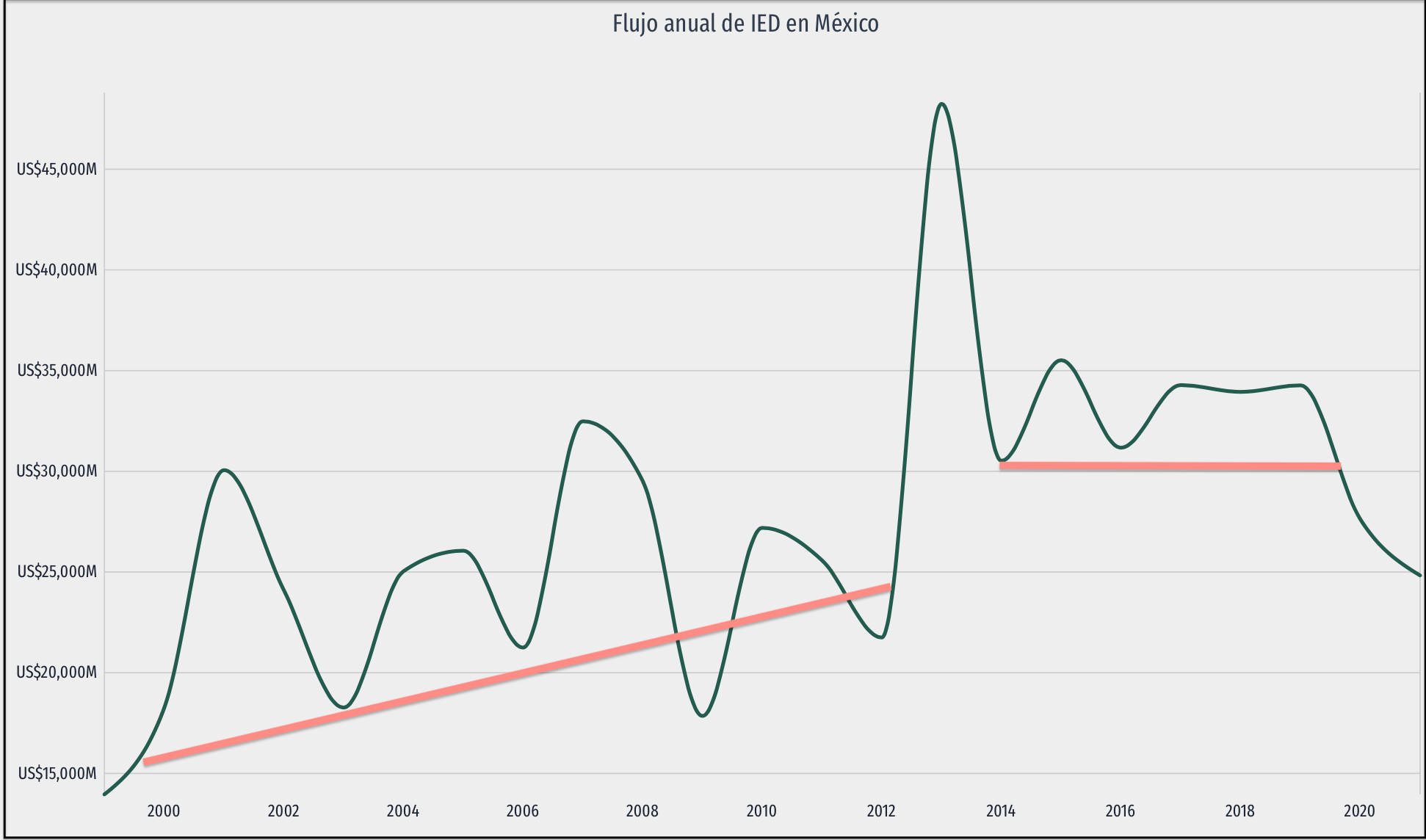

The point is that, delayed for so long, the reform materialised at the worst of times: in mid-2014 there was a collapse in the international price of crude oil and it was difficult to mobilise the expected investments. When the market began to recover, López Obrador's presidency arrived; his proclivity for statism has been favoured by a post-pandemic world context of retraction from the globalism that the planet had embraced. Moreover, the international oil sector itself is facing doubts derived from estimates of a not-too-distant consumption peak - in the midst of the take-off of the electric vehicle - and at the same time is seeing how large energy companies are redirecting their efforts towards renewable generation projects.

This context meant that the investments were not initially as abundant as promised, nor did they bring the benefits that Mexico had hoped for, both for Pemex's development and for the country's economic and social progress, so that the other side of the scale - the partial loss of sovereignty over its own resources - has weighed more heavily for many Mexicans. Some public opinion points out that concessions to foreign companies result in an accumulation of profits that are transferred abroad, with little impact on the country where they are generated.

The case of the Anglo-Dutch company Royal Dutch Shell has been pointed out, business , which in 2017 started extraction operations again in Mexican waters in the Gulf of Mexico after more than 80 years of absence since the oil expropriation. Shell has since reported a gross profit from its global operations (not just in Mexico) of over $226.995 million, transferred directly to its headquarters in The Hague. Inputs earned by other companies are also transferred to their foreign tax headquarters. Critics warn that only part of the fixed cost of transnationals remains within the country, which goes to pay the wages of national workers or to maintain the infrastructure of these companies.