In the picture

Haitian migrants, waiting for the management of their case by the US border authorities [P. Valtierra/Cuartoscuro/Amnesty Int].

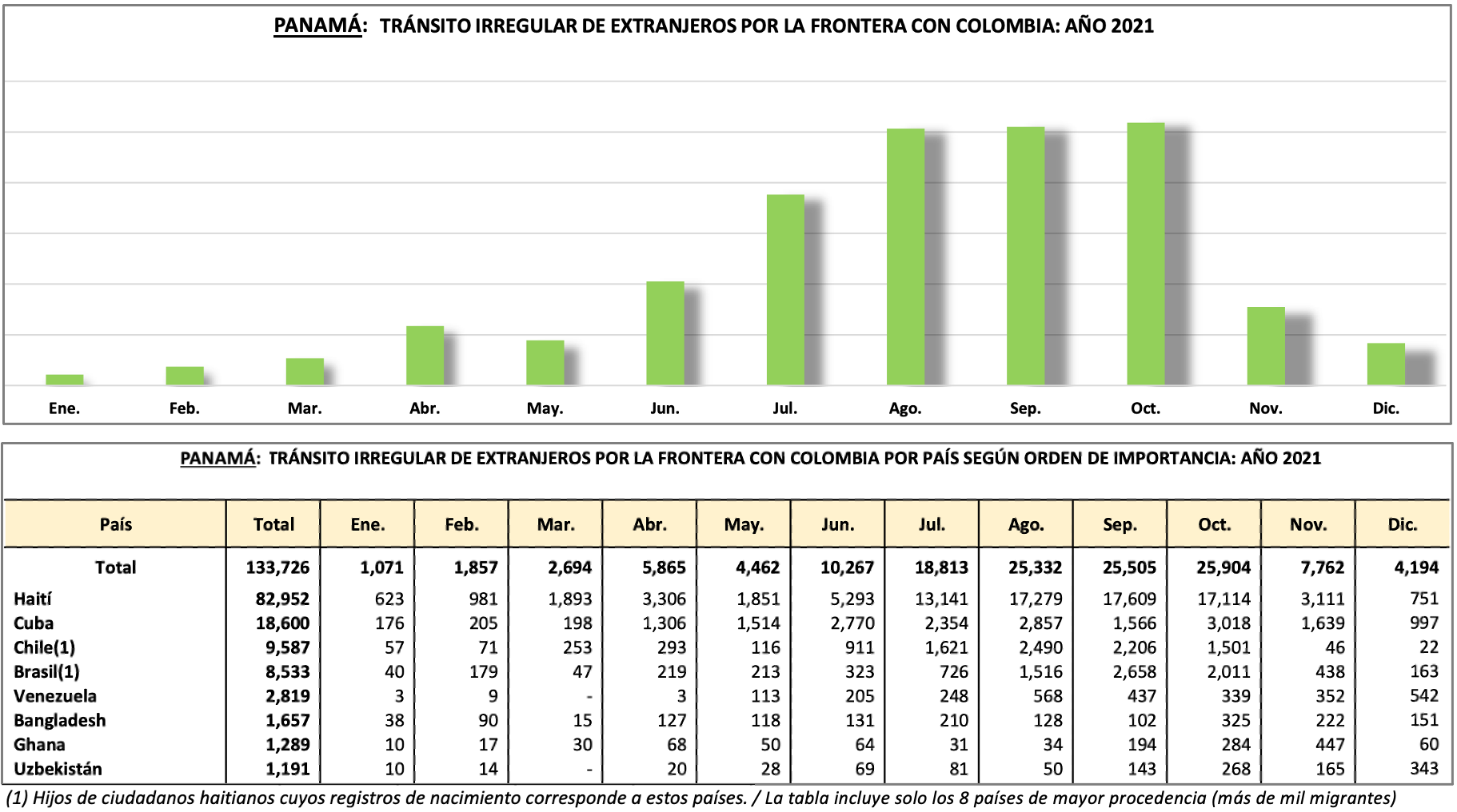

The main thermometer of migration from South America to the United States is the Darién Gap, the bottleneck that restricts passage from Colombia to Panama. A concentration of migrants there foreshadows a wave of pressure on the southern border of the US, in addition to that which may be generated from Central America. In mid-2021, a record arrival of Haitians was recorded in Darién, which shortly afterwards led to a crisis at the Texas border. The iron migration policy maintained by the Biden Administration and Mexico's partnership in trying to cut off the flow of migrants have meant that Haitian pressure in the Darién Gap has been reduced to previous levels.

Haitian migration and its redistribution across the American continent has been a constant in the complicated equation of migration flows in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, after the relaxation of the mobility restriction measures that had been put in place due to the Covid-19 pandemic, 2021 registered record numbers of migratory movements. The Haitian diaspora spread across the continent became the main actor in a new episode of mass exodus in the region, no longer from Haiti as in 2010, but from countries that have hosted Haitians as refugees over the last decade. This crisis involves an intercontinental journey towards the US that is concentrated on three different international borders (US-Mexico, Mexico-Guatemala and Panama-Colombia) and triggered a regional crisis in the management of these flows, mainly driven by the effects of the pandemic on the Latin American economy.

The progressive settlement of the Haitian diaspora in South America has a clear origin in the devastation caused by the notorious 2010 earthquake in Port-au-Prince, which according to data left more than 316,000 dead, 350,000 injured, 1.5 million homeless and a country with little capacity for recovery. The UN estimated that as a result of the earthquake nearly 4 million Haitians became food insecure, forcing nearly 2 million islanders to emigrate, many of them with their sights set on the United States and the promise of the American dream. However, the lack of options for travel to the US led thousands of Haitians to seek refuge in other countries. Brazil and Chile established themselves as the preferred destinations for Haitians: on the one hand, Brazil, which was in the midst of preparing for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Rio Olympics and therefore required an extensive labour force; on the other hand, Chile, due to the dynamic profile economy in macroeconomic terms. Thus, the main Haitian diasporas consisted, by August 2020, of more than 143,000 migrants in Brazil and around 175,000 in Chile. Both groups fuelled the perilous trans-American journey to the US in 2021.

The main cause of the Haitian flight was due to the effects of the pandemic in Latin America. In a region where 58% of workers have an informal employment , from agreement with data of the Inter-American Bank development (IDB), the effects of the pandemic hit Latin American society particularly hard: according to the March 2021 report of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), poverty and extreme poverty in 2020 reached levels not seen in the last 12 and 20 years, respectively; the pandemic led to a worsening of inequality indices in the region. South America in 2020 recorded negative economic growth of 6.6%, with the Brazilian economy falling by 4.1% and the Chilean economy by 5.8%. In both countries, Haitians worked mainly in the informal market and were affected by restrictions on mobility imposed during the pandemic. On this point, Sibylla Brodzinsky, UNHCR spokesperson for the Americas, warned that this impact on the economies also brought with it "an increase in incidences of discrimination and xenophobia", and therefore became another reason to flee to the United States.

Added to this is the arrival of Joe Biden in the White House with promises of greater empathy for the situation of migrants than for the US border. Following the assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse on 7 July 2021, Biden announced the extension of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to 55,000 Haitians and allowed another 100,000 to take advantage of the programme, which guarantees residency program and permission to work. The measure, which benefited Haitians who had managed to enter the country before 29 July 2021, also included expulsion or removal rules for those who arrived after that date. These removals took on particular significance under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) Title 42, which has allowed for restrictions on the entrance of aliens entering the US by land for health reasons, closing the border for non-essential activities, including asylum or refugee processing. The rules and regulations even authorised border agents to immediately deport undocumented foreigners, expelling more than 940,000 undocumented immigrants in the US fiscal year of 2021. This is a policy denounced by international organisations as "incompatible with international law", from agreement in the words of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi.

The problem worsened after the arrival at the end of September of 13,000 Haitians in the city of Del Río, Texas, where they camped out under the border bridge between Del Río and Ciudad Acuña (Coahuila, Mexico) awaiting a process to entrance to the country that never arrived. Instead, the US organised around 17 flights to deport more than 2,000 Haitians back to Haiti and not to their countries of origin where they had been residing for several years. The return flights were strongly criticised because of allegations that many migrants had been forcibly forced to board them. The remaining migrants moved to Mexico hoping for an early change in US immigration policy. In fact, a good part of the Haitians heading to the US remained concentrated in Tapachula, on Mexico's border with Guatemala, where, after the chaos in Del Rio, Mexican authorities had set up checkpoints to prevent more people from continuing their journey north.