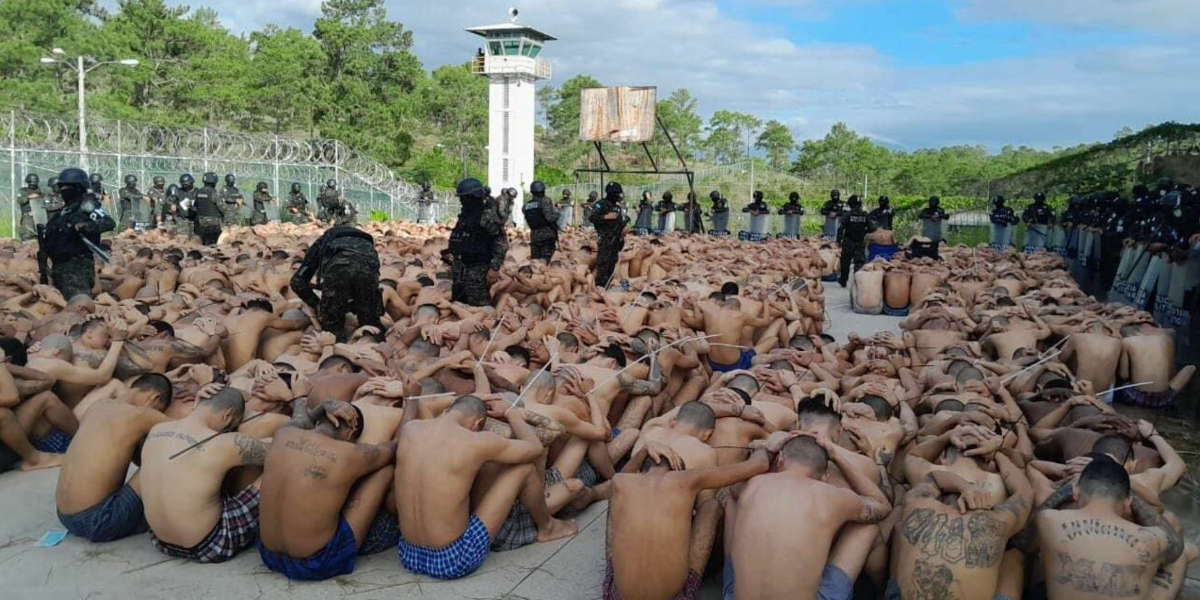

In the picture

Honduran police retake control of prisons after gang riots, in June 2023 [Gov.]

report SRA 2024 / [PDF version].

° President Xiomara Castro decreed a state of emergency in December 2022; in March 2023 she announced the upcoming construction of two maximum security prisons.

° El Salvador is a smaller country, the president has negotiated under the table with the gangs and about a third of its members have fled, some precisely to the neighboring country.

° Honduras also faces the problem of drug trafficking, Castro has fewer levers of power than Bukele and in Honduras there is a greater complexity of police forces.

El Salvador and Honduras have been plagued by the same problem for decades. The gangs have turned both countries into two of the most dangerous nations in the world and with the highest homicide rates in the entire continent fees . Originating among Central American immigration in Los Angeles, the Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18 gangs expanded since the 1990s into El Salvador and Honduras - to a lesser extent, Guatemala - once the wars that had driven out the population there ended.

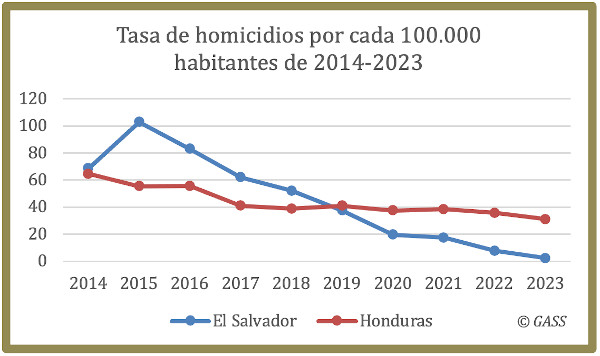

After some previous unsuccessful attempts at mano dura in El Salvador, the election of President Nayib Bukele in 2019 marked a considerable change, and his success in reducing violence has been replicated in other countries, including Honduras, where some similar measures have been implemented without a clear reduction in the homicide rate so far. The greater presence of drug trafficking in Honduras, through which the Colombian cocaine route to the United States passes - El Salvador is somewhat more marginalized - may explain this difference, in addition to the more omnipotent power exercised by Bukele, at times with dystopian overtones.

Until the beginning of the present war against the maras, it was estimated that there were between 30,000 and 60,000 active members in El Salvador, practically doubling the 25,000 to 36,000 in Honduras, even though the population is a third smaller (counting also the people around them who are partially involved, in the Salvadoran case, issue reached 300,000).

Homicide rate

Upon his arrival to the presidency, Bukele launched the Territorial Control Plan, in order to put an end to gang members. This project was based on three fundamental axes: attacking the gangs' finances, cutting off their communication in the prisons and recovering the center of the big cities. Bukele gave an important role to the Armed Forces, substantially increasing defense spending, and proceeded with the construction of a mega-prison, making El Salvador the country with the highest rate of people in prison in the world.

At the same time, there has been an arbitrary policy of detention and imprisonment of alleged suspects, and an abusive attention in prisons, as Human Rights Watch has denounced. During this war against the maras, Salvadoran authorities have captured more than 68,000 people. The application of the state of emergency since March 2022, there have been detentions without judicial guarantees, extreme overcrowding in prisons and a high number of deaths in prisons.

In this time, El Salvador has gone from having the world's highest homicide rate of 104 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2015 to 7.8 in 2022 and 2.4 in 2023. In Bukele's words before the UN General Assembly in September 2023, "El Salvador has gone from being the most dangerous country in the world to being the safest country in Latin America" and "competes with Canada for being the safest country on the continent." Bukele's high popularity, over 90%, led him to a landslide victory in his February 2024 reelection.