The EU aims to reach 20% of global semiconductor production by 2030, up from 10% today. As well as preparing a European Semiconductor Law, it is seeking a agreement with the world's leading companies, Taiwan's TSMC and South Korea's Samsung, to set up part of their production in Europe, and has secured the commitment of the US's Intel for a major investment on the continent. But for the plans to be effective they will require significant public support, which is always conceptually thorny.

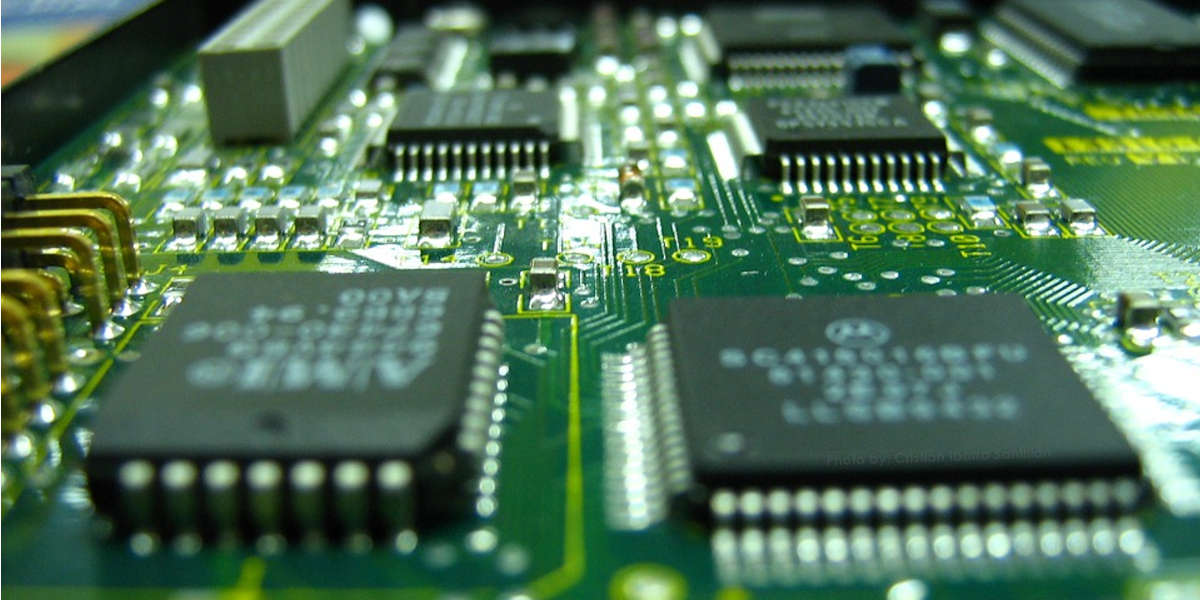

Semiconductors, also known as chips, are the basis of the digitalised world we live in. From automobiles, to the mobile phones and computers we use in our daily lives, they require these chips to function. This sector has grown globally from a value of $33 billion in 1987 to $433 billion in 2020. And with the increase in digitisation that we are experiencing year after year, the figure is only going to continue to rise.

The semiconductor sector is characterised as a capital-intensive industry (requiring heavy investment) and a high level of specialization, demanding highly advanced technology and materials. This has led to a concentration of the production process in a few countries. Most of the world's production - 70% - is in Asia; the main producers are Taiwan and South Korea, which together account for 43% of production.

The global crisis in the chip sector

The semiconductor industry is in crisis due to the pandemic. The proliferation of quarantines around the world led to an exponential increase in sales of ICT products (information and communications technology goods) and cloud services, which make use of chips. Production could not match the amount of demand and since then there has been a bottleneck in the market and a shortage of semiconductors.

The global shortage of chips is considerably affecting multiple sectors such as the technology sector. Giant companies such as Apple and Samsung have had to delay or slow down the production of their products due to a lack of chips. And in the video game sector, the new generation of consoles, Sony's PS5 and Microsoft's Xbox Series X , are not meeting the demand and it is an odyssey to get hold of one.

But one of the hardest hit sectors is the automotive sector, whose value chain is highly fragmented and much of it is offshored to other countries. The shortage of semiconductors is wreaking havoc on production lines. It is estimated that the automotive industry will stop producing 7.7 million vehicles and lose $210 billion.

This crisis has revealed the seams in the sector, with manufacturing being overly concentrated in too few locations. Affected sectors such as the automotive sector are seeing that the solution is to localise supply chains more, moving away from offshoring to onshoring or nearshoring models. And major states have already started to design plans to achieve a certain degree of autonomy in this vital and strategic sector and to stop relying on Asian production.

The United States was among the first to act, in November 2020, with the so-called "Chips for America Act", an initiative that will provide significant investments and incentives for the production, research and development of semiconductors in the country.

The European response

The European Union has already taken the plunge and this past year has already been showing its plans. In July, the Commission launched the "European Alliance on Processor and Semiconductor Technologies", which aims to bring together the efforts of Member States, companies, researchers and technology organizations. The goal of this alliance is to identify and address current bottlenecks, needs and dependencies in the sector. It also aims to devise a plan for Europe to be able to design and produce the most advanced chips. This would reduce global strategic dependence, with the Commission's goal being to reach 20% of the world semiconductor market by 2030. The Union currently has 10% of the world market.

In September, during the State of the Union speech , the President of the European Commission, Ursula Von der Leyen, announced that work is already underway on a new European Semiconductor Law. This law aims to promote a favourable ecosystem for the production of semiconductors in the EU, with the purpose main objective of guaranteeing their supply, as well as reducing European dependence, a question not simply of skill, but of technological autonomy. In her speech, Von der Leyen linked semiconductors to the success of European digitalisation, one of her main objectives since she became President of the Commission.

For the success of this law, the aim is to coordinate the research, the design and the review, as well as European and Member States' investment in the entire value chain of the sector.

This whole plan that the EU has set in motion can be framed within the search for the longed-for "strategic autonomy". The EU's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, defends this position in order to allow Europeans to take "control of their own destiny". And thus avoid the dependence that Europe already had, for example, with masks or antibiotics during the worst months of the pandemic, or in the energy sector with its dependence on foreign supplies.

There are also rumours that the Commission might be willing to ease restrictions on state aid to the semiconductor industry. Countries such as France argue that without more state intervention they will not be able to compete with major powers such as the United States or China to gain a stronger foothold in the market.

But the EU should not rely exclusively on strategic autonomy, but also seek commercial allies to attract production plants to Europe. Steps are being taken in this direction as well. Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Bretton of France was on a tour of Asia visitingJapan and South Korea with goal to sign digital association agreements.

The Union is also trying to attract the chip giants to Europe. Attempts have been made to reach a agreement with the world's two leading semiconductor producers, Taiwan's TSMC and South Korea's Samsung, to set up part of their production in Europe. And agreement has been reached for the American business Intel to invest in Europe with a plan of more than 80 billion euros over the next decade to set up chip factories.

Ambitious plan, but not enough

Despite the ambition of the EU's plans, it remains to be seen whether they will be sufficient, for a variety of reasons:

The characteristics of the sector, such as its high concentration and specialization, do not favour the entrance of new competitors. It is a market that is controlled by consolidated players from Asia and the US, so that the EU's entrance as a relevant player would be complicated.

The Commission's target of reaching 20% of the world semiconductor market by 2030, goal , does not imply that the EU will play a significant role. The figure that today Europe accounts for 10% of production is misleading. It actually reflects the fact that the EU has 10% of the entire subject semiconductor market, and most of the semiconductors produced are not among the most advanced on the market. The only ones capable of producing the most advanced chips are TSMC, Samsung and Intel. So to become truly relevant in the sector, Europe would have to be able to manufacture them.

For the plans to be effective, significant public support will be required. The US plan includes a $50 billion aid package for the sector, and China is counting on spending $170 billion between 2014 and 2024. The sector is experiencing a "degree program of subsidies", so if Europe is to be a major player it will need to convince states of the importance of public investment, and the EU should approve a budget package or complementary aid to compete with the main rivals in the industry.

And finally, according to a study by the Boston Consulting Group, operating factories in Europe is more expensive than in Asia or the US, so attracting chip factories to the EU will be more difficult.

At final, the European Union's plan to become digitally autonomous in the semiconductor market is very ambitious, but to make it a success will require investment incentives and development to support European companies and attract companies to Europe, public support and above all time.