In the picture

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan at a meeting held before the latest tensions [Gov. of Greece].

In recent months, the verbal escalation between the governments of Turkey and Greece has strained relations between the two neighboring countries, which share not only a land border subject to migratory flows, but also a disputed maritime delimitation, in an increasingly complicated Eastern Mediterranean.

The episode of a hundred migrants found naked in October in the Evros River, which separates Turkey and Greece, has stoked tensions between the two countries. Athens accuses Ankara of using migrants to create problems in the European Union, while the Turkish government accuses the Greeks and other Europeans of refund migrants indiscriminately.

On the other hand, several recent Greek moves to militarize some Aegean islands have raised Turkish alarm. With various maritime delimitations in question, Ankara may interpret some of these moves as provocation by its neighbors.

Next year's elections in the two countries (Turkish presidential elections are scheduled for June and Greek legislative elections for August) may be fueling both governments' interest in cultivating the nationalist vote.

In fact, statements by the political leaders of both countries show how Greek-Turkish relations are mired in the rancor of past conflicts. The speeches are replete with comments on historical disputes such as that of Smyrna in 1922, mentioned last June by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who referred then to the expulsion of Greek troops from the present-day Turkish city of Izmir, "throwing the infidels into the sea" and thus ending the Turkish War of Independence (1919-1923).

While an armed confrontation between Turkey and Greece, partners in the Atlantic Alliance, seems unlikely, the evolution of nationalism and the realization of a growing enmity opens up uncertainty about the future. Below, we examine here three possible scenarios on the development of the underlying conflict.

Migratory tension

The political status between Turkey and Greece has again become tense after 92 people were found trying to cross the border of the two countries across the Evros River on October 17. These people, who claimed to be asylum seekers in Turkey, were mostly from Syria and Afghanistan, and accused the Turkish government of a "humiliating" attention towards them. They were found naked and without belongings.

The Turkish government's communication director , Fahrettin Altun, responded to the accusation with the phrase: "The Greek fake news machine is at work again". In this way, the Turkish government denied having treated its refugees in a derogatory manner, without ever clearly explaining how 92 people were abandoned in Evros, apparently stolen and placed there without their consent.

Turkey and Greece do not exactly enjoy a good reputation when it comes to the reception of migrants. They are internationally recognized for their mutual accusations of mistreatment of migrants. Frontex, the European Union's border agency, has been accused of not accepting migrants on European soil and turning them back at the border of countries bordering its territory. But the Greek government and Frontex strongly deny carrying out these illegal returns of migrants, while Ankara emphasizes them, affecting the image of Frontex and the Greeks.

To address this irregular migration that has been occurring for years, in 2016 the EU established several principles such as, for example, that all new illegal migrants arriving on the Greek islands be returned to Turkey if they do not have proper documentation. The EU decided on this policy in light of the dramatic increase in human trafficking through the Eastern Mediterranean migratory route.

Maritime conflict

The maritime boundary dispute between the two countries dates back to the first third of the 20th century. Since then the sovereignty claim over 6 nautical miles from the coastline has pitted Athens and Ankara against each other, as many Greek islands (some disputed by their neighbors) are very close to the Turkish continental shelf.

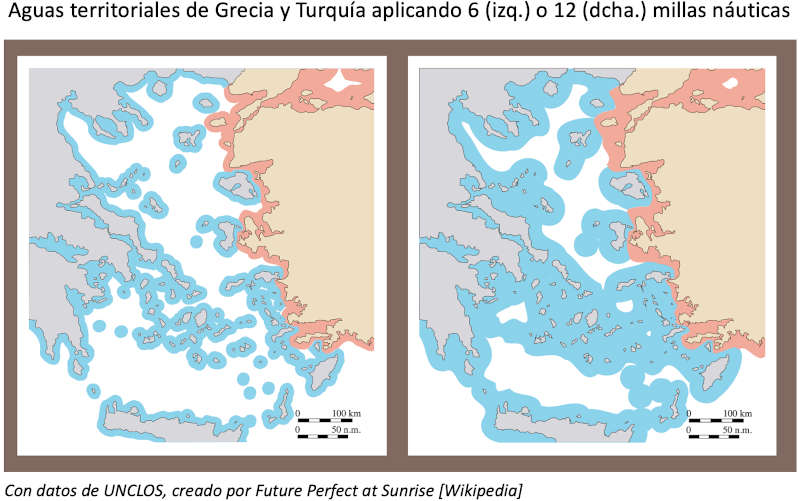

The United Nations proclaimed in 1982 the Convention on the Law of the Sea, which entered into force in 1994. The Convention grants states the possibility of claiming sovereign waters up to 12 nautical miles from their coastline. If Greece were to claim the 12 nautical miles, the Aegean Sea would become, 'de facto', a Greek lake. Turkey would be greatly harmed in the short, medium and long term deadline by this possible decision, so the Turkish government has stated on several occasions that it considers this possibility as a 'casus belli'. This has caused numerous diplomatic clashes between the two countries.

This maritime dispute has several nuances, since the continental shelves of these countries overlap, a problem that makes it advisable to apply customary tradition in default of the provisions of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Among several ways accepted by the UN to delimit a line average final , Greece prefers to establish a median line provisional between the Greek and Turkish island coasts, while Turkey is more inclined to take into consideration subjective factors relevant to the parties and maintains its initial position on the measurements of the median line, according to which the median should be calculated from the continental coastline.

This conflict has been especially alive since the 1970s. The delimitation of territorial and maritime areas, which could be of great financial aid for the Economics of both countries, is a point core topic of dispute. The control of airspace is also of great importance, since, militarily speaking, controlling flight information and air activity in the area is a great asset for any power.