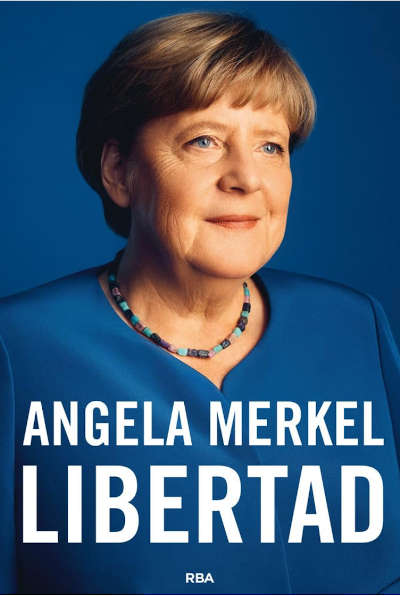

In the picture

Cover of Angela Merkel's book 'Freedom' (Barcelona: RBA, 2024) 812 pp.

As a genre, memoirs have their detractors because they are often driven by the desire to justify oneself to others and to history. But that is precisely its value: to understand why a leader, as in the case of Angela Merkel, acted in such and such a way. It is only fair that a person who has been at the pinnacle of public service, who has been subjected to praise and criticism as a result of actions or statements of which possibly only a reduced or mediatized version has reached the public, should have a space in which to explain herself. Merkel does so in 'Freedom', a volume that is in itself extensive but which covers more pages because of the generous font size (written in partnership with Beate Bauman, the head of her office for decades).

The degree scroll is certainly not very original, but in this case it has a plenary session of the Executive Council biographical sense. Growing up in the GDR, where the fact that she was the daughter of a Lutheran pastor further restricted her opportunities for advancement staff already severely limited for everyone by the state's Marxist-Leninism - Merkel immediately took advantage of the freedom that was opening up through the first holes in the Berlin Wall. She immediately put aside her work as a researcher in the field of physics and joined a fledgling political party (Democratic Awakening, later integrated into the CDU). As a chance spokesperson for this small group, she was able to project her analytical and argumentative skills, which led her to an advisor position in the first democratic government of the GDR; from there she moved to the national leadership of the unified CDU and the government of Helmut Kohl, first as Minister for the Family (1991-1994) and then for the Environment (1994-1998). As Vice-President of the CDU, the scandal of illegal donations that eventually engulfed Kohl catapulted her to the top, where she became Chancellor from 2005 to 2021.

The opening chapter, devoted to her life during the GDR, is the most trivial; nevertheless, these memories of everyday life in a communist system are illustrative of a time that we perhaps happily take for granted will not return; Merkel insists on the desirability of a constant appreciation of the freedom and democracy won. The other chapters are prolix in political meetings and summits of ministers and leaders, in the routines maintained from the chancellery and in the internal sessions required by the laborious task of governing in coalition. The latter is one of the political highlights of Merkel's statesmanship: all policies had to be discussed not only between the CDU and the Bavarian CSU, but also with the liberals of the FDP and the Social Democrats of the SPD, depending on the legislature. To stand up strongly for one's own ideas and at the same time to have to find intermediate paths so that they can be at least partially implemented - in dialogue not only with the partners in government or with the civil service examination, but also with employers, trade unions and associations of all kinds subjectis the exercise of freedom which, according to Merkel, is the backbone of democratic societies.

The book has something of a guide for the good ruler, as Merkel gives some behavioral advice and points out some missteps that she could have avoided. Anyway, one of the criticisms made of this memoir is that the former German chancellor does not admit to having made any big mistakes. But this is the honest thing to do, if you see it that way. For example, in retrospect she ratifies as right, given the circumstances and the values of German society, the 2015 decision to let thousands of would-be asylum seekers arriving from Syria into Germany, perhaps the most controversial of her terms in office. Merkel warns that the borders were not opened wide, but measures were taken to control many other migratory flows, but believes it would have been counterproductive to forcibly stop a march of refugees fleeing a civil war and wanting to reach Germany at all costs. He does not see himself as the manager of the Alternative for Germany vote increase.

Nor is there any 'mea culpa' for not having prepared Germany to face an increasingly assertive Russia in Eastern Europe. Merkel points out that her relationship with Putin was getting worse and worse, but that she had to keep an open channel of conversation to try to resolve the conflicts that arose. She presents the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline as an industry rather than a government project and justifies its planning by the pressure felt by companies and public authorities to reduce coal consumption through the use of gas and to deal with the discussion on the nuclear moratorium. The only doubt about what might have happened otherwise is not about his actions, but about Covid: he argues that, without the pandemic and the impossibility of personal contacts with other leaders, perhaps more pressure could have been exerted on Putin and the invasion of Ukraine could have been prevented. In any case, he insists that, for the good of Europe, Russia should lose this war.

Despite this forcefulness, the book lacks a fundamental consideration of what, for Germany, is the 'raison d'état' in its relationship with Russia. Merkel uses this expression not 'à la' Richelieu, but rather as a warning that there are positions or attitudes that give a raison d'être to a state such as Germany. Within this raison d'état she includes -indirectly, because she does not address it in those words- understanding with France, and, expressly, doing everything possible to help Israel to preserve its security. But from a German stateswoman one would expect some reflection on the geopolitical relationship between the two great European continental powers.