In the picture

Installations of the Medgaz gas pipeline linking Algeria and Spain [Medgaz].

The winds are blowing hard in Europe and the world. The current crisis in the East has not yet been resolved and everything suggests that, whatever happens, the aftermath will last for years or decades. Russia's gamble will certainly not help the West regain confidence, if it ever had any, in a country that every day seems more and more like the heir to the Soviet Union or even the tsarist empire. Perhaps because its aspiration is something akin to a mixture of both eras. But what cannot be denied is that the extent of the consequences of what, even today, as we write these lines, is yet to happen, cannot yet be calculated. But everything suggests that it will be decisive and that it will contribute to a new configuration of the world's geopolitical landscape.

And while there are those in Spain who believe that Ukraine, the Donbas and Russia are a long way from us, we should not allow ourselves to be carried away by this illusion. The consequences will be felt in this corner of the Mediterranean as much, if not more, than anywhere else. It has been repeated on numerous occasions that conflicts are interconnected in one way or another, the communicating vessels between them are frequent, and economic consequences often flow through one of these vessels.

One thing that cannot be overlooked is that Spain's geographic statusgives it a fundamental geostrategic character, with all the positive aspects that this entails if one knows how to play this trump card well, and with the negative aspects when it comes to receiving the impact of apparently distant crises. Against this backdrop, the long-standing alliance between the former Soviet Union and Algeria, maintained and subsequently reinforced by Russia, is of vital importance in the current scenario.

While military cooperation subjecthas been the traditional focus of relations between the two countries, economic relations have undergone a discreet evolution in line with common priorities and interests. These relations date back to Soviet times, although the Soviet Union was cautious in the early stages of Algeria's independence. A clear example of this initial stance is Nikita Khrushchev's statements to the first president of an independent Algeria, Ahmed Ben Bella: "we cannot maintain a second Cuba; you have a good partner, General de Gaulle, keep him".

A decade later, Algeria, despite remaining among the groupgroup of 'non-aligned' countries, was already maintaining very good relations with Moscow, which were mainly manifested in the supply of Soviet military equipment in the context of high tensions with Morocco. By the end of the 1970s, 90 percent of Algeria's war materiel was of Russian origin.

But relations between the two states went beyond the mere acquisition of weapons systems. The Soviet Union contributed to developmentthe Algerian mining sector and financed the opening of trainingand university centres that attracted not only Algerian young people, but also young people from other Arab and African countries. The resultwas that large numbers of engineers and professionals of all kinds, including army officers, benefited from the trainingprovided by the Soviets, and this was accompanied by an important cultural exchangein the form of intermarriage and learning language.

Over time, the remnants of this USSR influence have dissipated and become increasingly rare. However, professionals trained in this way rarely constituted part of the country's elite. To give just one example, the presidency of Sonatrach, businessoil company founded in 1963, was regularly held by US-trained engineers. Meanwhile, in the armed forces, the presence of high-ranking officers trained in the former USSR was significantly high. The current Chief of Staff, Said Chengriha, trained at the Voroshilov academy in the 1970s, and his predecessor, Ahmed Gaid Salah, who died in 2019, became the country's strongman after the latest popular uprisings (Hirak) and triggered Bouteflika's ouster, also trained in the Soviet Union. It follows that, of all Algeria's centres of power, it is in the armed forces that Soviet influence has lasted the longest.

To fully understand Russian-Algerian relations in all their complexity, beyond the myths of an unbreakable alliance, it is essential to look at three sectors core topic: energy, economic and trade, and arms, as well as two fundamental issues, their common geopolitical stance and Russia's position on the Hirak. This paper aims to focus on the energy sector.

As far as oil is concerned, relations between Algeria and Russia can be reduced to relations between the Kremlin and OPEC, which are conditioned by two contradictory coexisting realities: on the one hand, a constant pulse fuelled by the role attributed to the organisation in the fall of the USSR, when in the 1980s it considerably increased production, causing a drop in prices that further undermined the Soviet Union's battered status. And on the other, the spectre of Russian membership. Since 1993 Russia has participated in OPEC meetings while reaffirming its independence; but the trust required for full participation has never materialised.

It is important not to lose sight of a very important fact that conditions Russia's behaviour in many scenarios, in relation to its medium- to long-term aspirations deadlinein the Arctic area, taking into account that for Moscow to make oil extraction in this region profitable, the price of a barrel of crude oil must be above 80 dollars. As long as this is the case, dialogue with other oil-producing countries and exchangeare more than enough for Russian interests. However, until the outbreak of the current crisis in Ukraine this has not been the case, with prices dropping below $50 due to the fall in demand due to COVID 19 and the underlying crisis it has created, increasing the usual tensions between the organisation and Russia. But it is clear that at least as far as crude oil is concerned statushas changed, and the same is true for gas.

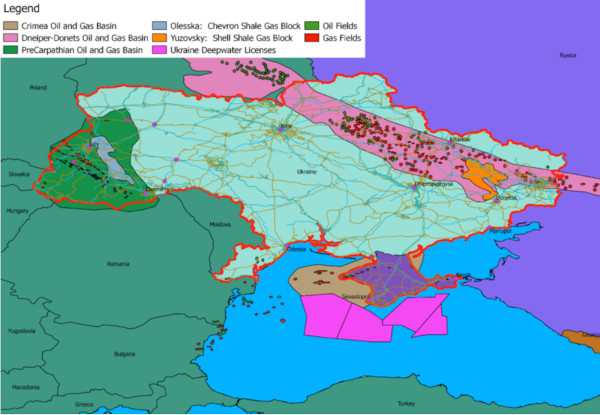

Algeria is, like Russia, a major gas producer, and both have Europe as their main customer. This, although at first glance it may seem to make them competitors, transforms them into allies. Although in recent years it has been taking steps to exploit fracking gas, for which it has even had the support of US companies, Algeria has shown a certain anxiety when it comes to multiplying its prospecting in search of this coveted resource resourceand exploiting those already found, which has led it to relax legislation with the intention of attracting foreign investment from Europe and the US, but also from Russia. An example of the latter is the protocolof partnershipsigned in 2020 between Sonatrach and the Russian company Lukoil, although it is also true that this has not yet materialised into anything concrete.

Looking again at what is happening in Eastern Europe, and the implications of these relations, two scenarios can be established initially:

On the one hand, the diversification of Russian investment outside the orbit of countries that might at any given moment lend themselves to support the sanctions imposed on it for its actions in Ukraine is a smart move that could help Moscow to partially circumvent the consequences of these sanctions; given the Russian mentality and the way events have been unfolding, it cannot be ruled out, but rather it is likely that it is all part of the same plan. On the other hand, Russia needs to consolidate its economic relations, especially in the energy sector, in a country that traditionally belongs to its orbit and owes it so much, and which needs its support in its struggle with Morocco to be the dominant regional power, given its role as the second largest gas supplier to Europe. Russia can not only use Algeria as a disruptive element in US policies in North Africa, which rely mainly on Rabat, but can also, in a sense, take control of almost 90 per cent of the gas supply needed by the European continent.

To better understand how Europe is linked to Russian interests, it is worth describing its current energy location. It is important to bear in mind that Europe lacks non-renewable sources of its own, which has led it to acquire a whole network of gas pipelines that make Russia its providerwith 40% of the total. In other words, Moscow is practically the sole supplier of all gas in countries such as Sweden and Finland, and of more than half in Central European countries.