Moral image of the culture of life

Gonzalo Herranz.

departmentof HumanitiesBiomedical Sciences, University of Navarra.

lecturein XIII conferencede Bioética. La cultura de la vida.

Pamplona, 26th and 27th October 2001.

Understanding with the misguided

I am going to try, with the suspicion that what I am going to say is still in a very immature stage, to make a strong and hopefully stimulating topic. There are many things that could be improved in what we have come to call the culture of life and I am going to refer to some of them. I believe they can be of value to a very wide audience: to those of us who walk the academic streets and to those who are active on the streets.

From time to time, one reads that Plato said that a life without examination is not a truly human life. The same is true of the culture of life: if we do not examine the things we do or that happen to us, if we do not keep our wits about us, the culture of life will wither in our hands.

To give meaning and freshness to the culture of life, it needs to be examined and it needs to be examined. There are many things that need to be brought into sharp focus in that task of examination, but today it is the turn of what we might call its moral profile.

There is a lot of talk about the culture of life, but it seems to me that little thought is given to it, little in-depth thought is given to it. "Culture of life" is certainly a very suggestive and catchy expression, which runs the risk of falling into triviality, into an empty slogan, and which, precisely for this reason, needs to be enriched and better defined in its content. It is in the interest of all of us to bring ideas and to refine them, in order to determine together what the culture of life is.

It is our turn today to think about his moral image. It is a rather basic topicto try to clarify the ethical genius, moral physiognomy, character and mettle of the culture of life. The culture of life is often or almost exclusively lived as activism: actions in favour of human life are essential. It is easy, then, to get lost in questions of means, tactics and priorities. But from time to time it is worth stopping to think, so as not to lose sight of its purpose and its mission statement. For a moment, it is worth stepping back from the maelstrom and taking a step back, as a painter does in front of his painting, to look at the whole and detect defects, correct strokes, refine nuances and fill ingaps.

Stopping to rectify the course is easier said than done. Because it is not a simple matter, I know I will not be able to present it adequately. I'm not sure I've got it right in the points I'm going to make and in the way I'm going to analyse them. But the thing is in the programme and I have to say something.

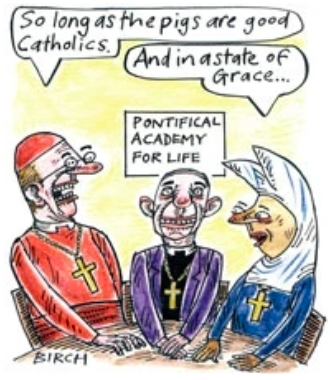

To start and put us in context, I am going to project a picture. I could, at this point, ask everyone to express their reaction: it is one of those bad jokes, which instead of amusing us, fill us with sorrow and worry. The journal Nature on 4 October published a news item in its news section entitled: Vatican approves use of animal transplants 'for human benefit'. The item, which took up a column, consisted of two parts. The first, informative, said that the decision of the Pontifical Academy to consider xenotransplantation as an intervention to which no fundamental ethical objections can be raised was something of a surprise and would undoubtedly have the effect of stimulating worldwide researchon animal-to-human transplants. The Nature correspondent highlighted a few points, which, if they did not do full justice to the Academy's document, did not hide its values and conclusions: all said with brevity. But the second part of the Nature column was quite another matter. The news was accompanied by the projected joke. It gives the impression that both the cartoonist Birch and the editors of Nature, unable to express their disagreement with the content of the Vatican document, unimpeachable even for the most radical scientism, wanted to take the opportunity to hurt the sensibilities of Catholics and mock that of the Pontifical Academy for Life.

Why can this drawing serve to put us in context? It seems to me that it is a symbolic joke, which reveals some important things. It reveals, first of all, that the strong scientism of the editors of leading scientific journals is not only strong and dogmatic: it is also exclusionary. The drawing does not samplesimply show that we Catholics are not very well regarded, and that some people enjoy hitting us where it hurts the most so that we feel discriminated against, so that we react with rage and hatred. The joke is, more than a punch, an invitation to leave the field of science and stop putting down the advances of research. The joke is an expression of the dissuasive, exclusionary language that is so often used from the camp of the culture of death. They want to irritate us and they want us to stay at home and leave the street to them.

But our reaction cannot be one of silence or withdrawal. The culture of life must have a higher moral profile. We have to speak out and be present on discussionand resort to intelligence, justice, civility.

resourceNo matter how bad things are, we can always reply with a letter to publisher; better still, if we are truly a living culture, with many and varied letters to publishersent from the four winds. I know that it is not easy to write a calm letter while one's skin is stinging, while the stick hurts, because it is easy then to practice the law of retaliation, to fall into aggressiveness, refundthe blow received with another, more forceful one, if possible. But this only leads to brief and useless sparks of violence. "Violence never. I do not understand it, it does not seem to me suitable either to convince or to win", are the words of Blessed Josemaria. There is a more dignified way of reacting, more humane and more Christian, which is to lament the error of others with true sorrow and compassion, not with contempt or insult, and to respond with reasons: not only those that articulate our convictions, but those that can make those who have attacked us think. That requires an effort, more or less great, of charity, of intelligence, of study, of striving to feel compassion, not hatred, for those who are wrong and make us the object of their foolish jokes.

[I don't want to make an example of myself, and I have already begun to see flaws in the letter I sent to Nature. But this is what I wrote to them: "Sir - Birch's joke added to the news item about the Pontifical Academy for Life's reporton xenotransplantation (Nature 413:445;2001) was unnecessary and tasteless. It was extraneous to the content of the news item and added nothing of value to it. Moreover, it hurt the feelings of many of its readers.

As I see it, good humour plays an important but neglected role in scientific communication, which often needs the stimulating effect of a spark of joie de vivre. A fair amount of irony is good, but too much acid burns the skin. Please continue to include jokes in the pages of Nature, but demand the same Degreequality and decorum for them that you require for the other parts of the journal. I think jokes can bypass the refereed review process, but they need careful consideration before they go to press.

In passing, I would like to tell you that the Pontifical Academy for Life is a respectable institution, in which, as I can testify, there is a deep and sincere respect for science"].

I don't know whether my letter will be published or not. For me, it has served to temper my irritation, to say the essentials of my displeasure and to present myself to Nature's publisherin a friendly spirit. I do not hide our differences of opinion, I defend the good reputation of the Pontifical Academy, I show that I like good humour, and I give my opinion on its role in biomedical communication. Nature's publisher, who, despite his prejudices, I am sure is a competent professional, will be in the dilemma of whether his professionalism or his prejudices will prevail. If there were many of us who had written to him firmly and in a good tone, I could not help thinking that those in the culture of life camp are ordinary citizens, numerous and reasonable, who have a sincere appreciation for science, but who do not keep their mouths shut when they are gratuitously attacked. He will not publish the letter, but it is certain that, in the future, he will proceed with a little more caution. And that is important.

Receiving scorn and put-downs when we are on the side of life cannot lead us to feel marginalised first and excluded later, and end up becoming resentful and bitter people. That would be a very bad thing, as it would put us at risk of becoming irrational and violent, both as individuals and as a collective. If that were to happen, the culture of life would be lost.

It is therefore necessary to work on building the basic moral profileof the culture of life, on defining its moral image. This profileand image must combine unity in what constitutes the fundamental nucleus of respect for the life of all human beings, with the infinite variety of ways of being, traditions and contexts of the wide world.

Enough of this introduction and let's get down to business.

What follows is a preliminary study, an outline of a very broad subject. I hope that it can be enriched by your observations and criticisms in the subsequent exchangeof ideas. Apart from being preliminary, it is partial, for I will deal with only a few of the many aspects that make up the moral image of the culture of life. I will deal with these four features of the moral profileof the culture of life: serene humour, understanding for the misguided, commitment to truth, and an affirmative sense of purpose.

The culture of life cannot be built on resentment or sadness. In Evangelium vitae, which is to be like a guideto which one must continually return to refresh ideas and take heart, the Pope tells us that joy for life is an essential element of the culture of life. There are purely human ways of basing the serene joy for human life: for some, this joy comes from the idea of respect and admiration for nature; for others, from the attitude of veneration for life; for still others, from the recognition of the special dignity of the human being; for others, finally, in belonging to the species Homo sapiens.

The joy for human life of which the Pope speaks to us in points 83 to 86 of the Encyclical is on another level. The Pope comes to tell us that without joy, without the joy of the Holy Spirit in the soul, it is not possible to build the new culture of life, nor can the humble and grateful awareness of being a people for life take root in us. For promotethe necessary and profound cultural change to which the Pope invites us, it is necessary to present ourselves to people with calm joy, with a smiling countenance, with serenity in what we say, do and write.

It is worth pausing for a moment to see what the Encyclical Letter tells us about the joy inherent in the culture of life. It reminds us on its first page that, at the dawn of salvation, the birth of a child is proclaimed as joyful news: " advertisementbrings you great joy, which will be for all the people: to you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, who is Christ the Lord" (Lk 2:10-11). In this way, the Pope shows us that joy, and in particular messianic joy, is the foundation and the height of joy for every child who is born. Joy is at the heart of the new culture of life1. The Pope goes on to present the scene of Mary's Visitation to Elizabeth as an outburst of joy for life, in which both the fruitfulness and the eager expectation of a new life and the value of the human person from conception are celebrated and depicted2.

At the beginning of Chapter IV of the Letter, the Pope tells us that the tasks of proclaiming, celebrating and serving the Gospel of life are inseparable and that each one must fulfil them according to his own charism and ministry, thus bringing together unity and diversity, fidelity and spontaneity3. The Pope concludes by affirming that this joy for life must fill the whole of existence, and that we must sow it throughout the wide world, in the boundless field of the whole of existence4.

In points 83 to 86 of the Encyclical, which deal at length with this joyful dimension of the Gospel, of the new culture of life, John Paul II offers us a set of ideas, gentle and strong, which, if we were to assimilate them thoroughly, could give our dialogue with people much freshness and the ability to overcome prejudices and difficulties. He tells us:

- That we are to have an attitude of joyful wonder in life. Based on the words of Psalm 139/138 - "I thank you for so many wonders: I am a wonder" - the Pope, with keen psychological intuition, reminds us that we are in the world as a "people for life" for the advertisementof joy in life.

- That this attitude is not mere joie de vivre, but resultto cultivate in ourselves, and to foster in others, a contemplative gaze, which leads us to consider that every human being has been created by the God of life as a prodigy, a miracle. It is necessary to look at human life in depth in order to be constantly amazed by its gratuitousness and beauty, by the promise of freedom and responsibility that is included in each life.

- That this penetrating contemplative gaze, respectful but not possessive, will reveal to us in each living person the living image of the Creator; it will make us see through transparency the intangible dignity of each human being, so often obscured by illness, suffering or the precariousness that precedes death.

- That this contemplative gaze finds meaning in every human life, for it discovers in the face of every human being a call to mutual respect, to dialogue and solidarity, to religious admiration for every human being, called to participate, in Christ, in the life of grace and in an endless communion with God the Creator and Father5.

- That the foundation of the culture of life lies in establishing in our conscience the joyful, clear and profound idea of the dignity of every human being, of all human beings. And this dignity, so often hidden by illness and obscured by ignorance, must nevertheless always be celebrated because it never lacks a spark of God's glory. Quoting Paul VI, the Pope tells us that even the mysterious contrast between life and death is an occasion for joy: "This mortal life, despite its tribulations, its dark mysteries, its sufferings, its fatal expiry, is a most beautiful fact, a prodigy always original and moving, an event worthy of being sung with joy and glory", for, adds John Paul II, "in every child who is born and in every man who lives and dies we recognise the image of the glory of God, glory which we celebrate in every man, sign of the living God and icon of Jesus Christ. "6

These ideas and others contained in points 83-86 of the Encyclical should be frequent reading for those working to build the new culture of life. Moreover, they should be offered with hope to those who militate in the ranks of the culture of death, so that they may come to know us and thus understand what is at the heart of our love for human life.

It is very important that we find the right affective tone core topicfor our words and our humour in favour of life. In Veritatis splendor, very early on, the Pope speaks of the effort to find "ever new and original expressions of love and mercy to be addressed not only to believers, but to all people of good will" and reminds us that the Church is an expert in humanity, a Mother and Teacher who places herself at the service of every man, of all men7.

Pro-life activism must be informed by joy. We are told in the Encyclical that the Gospel of life is for the Church not only a joyful proclamation, but in itself sourceof joy8. The culture of life is not a political conviction, or a school of demographic science, or a sociological way of evaluating community and family relationships. Deep down, the driving force that should move us to defend life with joy is the gratitude we feel for the joy of being alive, for the incomparable dignity of the living human being: Gloria Dei vivens homo, says the motto of the Academy, taken from St. Irenaeus of Lyon. This is an important and effective reason to share our message with those around us.

Often, when reading publications of pro-life movements, one misses the encouraging, joyful, celebratory spirit that should be an attribute of every pro-life action, of every pro-life gesture and attitude. There is too much party politics in these publications, too many personal references to the perpetrators of evil, too much localism, condemnations and insults, touches of Manichaeism. Many of these publications are not very inspiring, because they lack generosity and joy, intellectual strength and the ability to discussion.

In the battle for life, such generosity and joy are necessary for us. And also a bit of broad vision: we must also rejoice in the many wonders that are worked every day, in the form of conversion and repentance, of lives saved, of messages that seem lost, but which later will resound loudly. The new culture of life must be like the house of the prodigal son's Father, where, at every moment, the sorrow of loss is changed into joy at his return.

Understanding with the misguided ![]()

When the Pope speaks of the culture of life, he does not hide from us that, to a large extent, it is something that has its raison d'être in its confrontation with the culture of death. The culture of life has had to grow in order to oppose the culture of death. As we all know, what we now call the culture of life went from being something peacefully received, an implicit part of the inherited cultural background, to something active, explicit, problematic, which is at war with the culture of death. The Pope speaks of our being involved in an "enormous and dramatic clash between good and evil, death and life, the 'culture of death' and the 'culture of life'"9.

(Said in brackets. When the Pope refers in the Encyclical to this bellicose confrontation, he characteristically writes the expressions "culture of death" and "culture of life" in inverted commas10. By contrast, when he speaks of the culture of life as an affirmative and dynamic reality, self-sufficient and true, which exists by itself and stands on its own feet, which does not need to be understood as a reaction against aggressions against human life, the Pope usually refers to "the new culture of life, which is in itself creative and original, a fundamental part of a civilisation of love and truth "11).

Living in war is not easy. There is a risk, when fighting, that those who fight, those on both sides, will fall into the simplism of seeing only the idea that one is advocating. One can then fall into one-dimensional thinking. This risk is particularly dangerous for those who respect the sacred value of human life.

It must not be forgotten that to profess that man, the living human being, that all living human beings are equally valuable in themselves and possess a dignity which is identical in all, is both a profession of faith and a conclusion of reason. This is of decisive importance. Authentic religious tradition, while recognising that human reason can be wonderfully and effectively enlightened by revealed Truth, equally stresses that within faith there is a place for reason. Therefore, to present the dignity and sacredness of human life as a mere religious datum would be to fall into fideism, which is a form of one-dimensional thinking, of religious fundamentalism.

In the same way, to conclude that the claim that every human life is valuable in itself and is innately invested with dignity is a purely religious claim, irrational and unprovable, or that the tenets of religion traumatically divide people and make rational discussionimpossible because they induce error, is to fall into secularist reductionism. This is an equally one-dimensional way of thinking, which admits many variants, ranging from neutralism, to ethical relativism or sociobiological determinism.

Faith is falsified if it takes the form of a passionate prejudice. If faith, separated from charity, closes us off from dialogue with those who are outside it or against it, or with those who have distorted it, it would not be an authentic faith: it would be fanaticism. Even more, a faith that renounces the rational discussionand shields itself in the automatism of repeating slogans, stereotypes or coined phrases would be a faith reportand immature.

By the same token, it must be concluded that the radical and unqualified secularism, which many flaunt as the sole orthodoxy, is something that time has discredited as empty dogmatism. In this 21st century, no one with a critical sense believes in the Enlightenment myth of indefinite progress any more. We have seen and are seeing too many failures of science, too many situations of technological abuse, of domination of the strong over the weak with the partnershipof scientists, so many that there are no longer any among people endowed with moral sense who believe in scientism as a message of salvation for mankind, in the ultimate redemption by science.

In the confrontation of the cultures of life and death, the defenders of life cannot forget that faith must always be accompanied by charity and understanding. Those who defend death cannot be regarded as "unbelieving dogs" to be destroyed, or as vitandos heretics who must be kept away from and left to rot in error. There is no doubt that their actions and arguments are often partly wrong, sometimes even radically so. But we cannot condemn those actions without examining them closely, nor can we dismiss those judgements without refuting them and subjecting them to constructive and careful criticism. Such an attitude is tantamount to that which is so prevalent in the field of the culture of death, and which is so painful, of scorning without knowing, of mocking everything that comes from religion, of dismissing as irrelevant and false any allusion to transcendence, especially if it comes from the Pope. Nature's joke reveals how annoying they can be in our company: they don't want us to be agreementwith them, they resent us agreeing on anything.

But we cannot conform our conduct to their ethics. If we are to try to go beyond them, at least to fulfil the commandment of charity and thus be good children of our Heavenly Father who makes the sun rise and rain on the just and sinners, we must try to understand and excuse them.

"Blessed Josemaria said, "Even if their errors are guilty and their perseverance in evil is conscious, there is deep down in these unfortunate souls a profound ignorance that only God can measure [...] Always, keeping the order of charity, we should welcome with special understanding those who are in error. For it is only by understanding them that we can have attentionwith them and seek their friendship. We will then know how to make them see that, from a merely intellectual and formal point of view, we are not very different from them, nor they from us. We will show them that faith and reason are good companions; that truth - scientific and religious - is one, because it comes from God; that religion is accepted as the ultimate sourceof morality by many reasonable people, by many scientists; and that it is precisely faith financial aidthat helps them define the subjectperson they want to be, even if they do not always succeed in doing so.

And we can also tell them, as far as we are concerned this afternoon, that faith impels us to give the ethical speecha very important and enlightening dimension, which not only cures us of superficiality, but also "complicates life", because it prevents us from eliminating important fragments of reality, as they do by using their various reductionisms. They must recognise, if they overcome their exclusionary prejudices, that sincere religious conviction, cultural commitment to human life, cures the ethics of life of the disease of simplism.

In other words, we have to tell them that we are fundamentally alike. As Pellegrino has argued, those who trust in reason alone and do not grant even the slightest credit to religious faith, are also believers. If they have a minimum of intellectual finesse and recognise the abc of science, they must accept that they believe, as we do, in mystery. The non-believer is not, by virtue of being a non-believer, more rational than the believer. The difference lies in the context of the first act of faith. "While the religious person believes in an external sourceof faith, the non-believer (which is basically a misnomer, because he is a believer in his own way) makes a strong act of faith in his own intelligence, in the fundamental postulates of his science. He refuses to believe in that which does not convince him as he judges it by means of the ordinary criteria of verification. But this is precisely an act of faith, similar in a certain way to that of the believer in God, whose faith is placed, not in his own judgement, but in transcendental Truth".

This common ground can be used for dialogue, because it forces us to accept, in principle, that faith and rationality are on both sides. As Maritain showed, all argumentation within the reach of reason must necessarily start from certain prelogical presuppositions about the world: they originate in an act of faith, in an initial, irreducible belief. Some of us believe in God, others believe in reason, others in humanity, others only in money. The differences that separate us are not properly in the act of believing, in the act of affirming or denying a basic choice about good and evil, but in the fulcrum chosen to support the lever of reason. That they also believe can be seen in their firm faith in basic scientistic convictions, which can lead them, if they do not open them to the scrutiny of those who think differently, to such fundamentalist attitudes, in their intellectual stubbornness and in their contempt for critics and dissenters. In this they are not much different from the fanatics of certain religions.

In the culture of life, an important place must be given to understanding and apology. Uncharitable attitudes, which instead of refuting mistakes, condemn and despise people, do great harm to the culture of life. God alone is the judge: we do not know how strong the personal and environmental circumstances (ignorance, family history, sectarian Education, examples and counter-examples) may have been that have led some to align themselves with the ranks of the culture of death. Undoubtedly, there are activists in the culture of death who have been sucked into it because of their invincible ignorance, over-sensitivity, uncontrolled compassion, or harshly utilitarian or hedonistic sense of existence, circumstances from which, thank God, we have been spared.

The Pope gives us an example of this compassionate way of confronting evil. There is a moment in Evangelium vitae of enormous ethical vibrancy: it is the moment in which the Pope calls women who have had recourse to abortion to conversion to the Gospel, to the new culture of life. It is worth remembering, in order to perceive the ethical importance of the Pope's appeal, that abortion is incompatible with ecclesial communion: according to the current rule, those who deliberately abort are excluded from the Church. But the Pope nevertheless calls them and offers them forgiveness and a return home. He says of these women: "The Church knows how many conditioning factors may have influenced their decision and has no doubt that in many cases it was a painful, even dramatic decision. It is true that what happened was and still is profoundly unjust. However, we must not give in to discouragement or give up hope. What happened must be lucidly understood and interpreted in its truth. But there is still the great hope of repentance, of forgiveness from the Father of all mercy.

There is no finer or more eloquent dissection of the human drama of abortion, as a moral error, and of its rectification, in which generous understanding for the sinner and clear condemnation of the perversity of their action are juxtaposed; the apology and the appeal alongside the affirmation of how unjust what they did was.

The culture of life must be built in this human context of understanding for people and condemnation of mistakes. But, just as is beginning to happen in some sectors of medicine, we must change our attitude towards those who make mistakes and the mistakes they make. Neither hiding mistakes nor tolerating them leads to solving them or avoiding their repetition. Mistakes are combated by their sincere confession, the study of their causes and conditioning factors, the implementation of means to prevent habituation and recidivism on internship. It is necessary to create a social environment in which the ethical value of confessing error and being sorry for it is recognised. Everyone should be educated, from childhood, in the truth of repentance, one of the highest human acts of dignity, which John Paul II characterises as a synthesis of man's frailty with God's merciful love12.

The culture of life cannot be built on enmity or contempt for those who are wrong. It cannot be built on insults, put-downs or libels. It demands understanding, apology and forgiveness, in order to attract those who have fallen into error, however corrupt their mind, however fanatical their will, to open the way for them to return to the Father's house. It would be wonderful to give to pro-life activities this generous, understanding trait, which knows how to distinguish between the mistaken and the mistaken.

A systematic search in the text of Evangelium vitae for the word "truth" and related terms sampleclearly shows that the Holy Father gives truth the status of an essential element of the theory and internshipof the culture of life.

He speaks to us of the capital value of truth in spreading the Gospel of life, for only in a profound commitment to truth can man discover and spread respect for the humanity of every human being. The Pope tells us, among other things, these very strong things, which we must repeat to ourselves and to our friends: that sincere openness to the truth is a condition for the sacred value of human life to be revealed to man13; that every authentic social relationship must be founded on truth14; that now more than ever it is necessary to look the truth in the face and call things by their name, without giving in to the temptation of self-deception15; that in history crimes have been committed in the name of truth16; that the new culture of life is the fruit of the culture of truth and love17; that the workof the builders of the culture of life must express the full truth about man and life18; that in the means of social communication scrupulous fidelity to the truth must be exercised19.

And, by contrast, the messages of some of those who militate in the culture of life camp seem tainted with various forms of untruth: I do not mean that the authors of these publications deliberately use lies or deception. I mean that some have succumbed to the temptation of strategic efficiency, that good ends authorise the use of whatever data is at hand. Some have no scruples about exaggerating the truth or distorting it in an attempt to make it harder and more convincing. Or they torture it to make it reveal aspects that are not contained in it; or they reveal it in part and, at the same time, hide it in part, in order to avoid the inevitable complexity that reality often presents.

At other times, because of the urgency of statusor because of a lack of reverence for the truth, immature writings are disseminated, the fruit of improvisation, created in irritation or retaliation, which damage the cause of the culture of life and sometimes provoke the rejoicing of those who fight against it. They may then not only be untruthful and uncharitable, but also unwise for not having ordercommittee to those who could give it. Never, in the construction of the culture of life, should one skip the step of apply forconstructive criticism from those who can see the problem with more serenity and greater science.

The written publications or verbal manifestations of the followers of the culture of life should, insofar as they apply to them, comply with the quality standards that apply in the world of scientific and cultural communication. These standards, which initially referred almost exclusively to questions of style and label, have, over the years and with increasing intensity, incorporated certain ethical requirements20. Some of these requirementsare important in our context, as they translate an ethical attitude of intellectual honesty and informational integrity, requirementswhich immunise against the ever-present risk of using ethics for the sake of convenience. In the war for the culture of life, the perverse principle of "anything goes" does not apply.

The common ethics of publishing21 impose certain duties on us, including the following:

- the duty to check the truthfulness, accuracy and up-to-dateness of the dataused in our arguments by diligent research and critical selection of reliable sources of information, and to explicitly indicate such sources;

- the duty to reject any temptation to fabricate data, falsify testimony, or omit significant information;

- the duty to express with rationality, moderation and prudence the conclusions of our speech, so as not to consider as real what is only desirable, not to point out as certain what is doubtful, not to consider as proven what is merely hypothetical;

- the duty to take personal moral responsibility for what we communicate and disseminate in the context of the culture of life, in which there is no room for anonymous libel;

- the duty to ask for committeefrom those who can give it with skilland generosity. In the same way that peer review has meant a leap in quality for academic publication, asking for committeebefore publishing is, in the context of the culture of life, the best guarantee against haste and subjectivism. Asking and giving committeeis a great human and Christian treasure, which saves from the danger, sometimes too close, of being carried away by one's strong or obsessive ideas, especially when they are wrong or inopportune;

- the duty to acquire and practice an upright attitude towards intellectual authorship, which obliges us not to appropriate the merits of others, by means of plagiarism or imitation, but to grant, out of justice, the credit of originality to the creators of new ideas.

Some of these ethical errors in the field of pro-life culture promoters have recently been denounced, with much firmness and real-life examples, by Roberge22. His articleis worth reading, as it not only criticises the scientific and ethical deficiencies, amateurish deficiencies, that are occasionally found in the pro-life bibliography, but also points out some defects that contribute to keep in a rudimentary state the obtaining of well-tested scientific dataand to systematically dispense with the expert assessment, both things so necessary today for a vigorous action in favour of the culture of life.23

The culture of life is a culture of truth and love. That is to say, only in intellectual honesty, in the search for truth, in the effort to love and forgive, will the pro-life movements find their intellectual and ethical place. Dialogue with those who militate in the culture of death, I say this in imitation of a committeethat I heard Blessed Josemaria say, must often consist of studying and having people study. The sincere search for truth is the great hope for understanding between the two cultures, for God will not deny his lights to those who with commitment, simplicity and intelligence try to understand the value of human life.

From what I have just said it cannot be deduced that meetingwith the culture of death is a matter of course. The Pope is not exaggerating when he tells us that we are involved in a huge and dramatic clash between good and evil. We are in a war that will go on for years and years. What we read in the Bible is literally true: that man's life on earth is a militia. It is up to us to cooperate for life, to be tireless workers, each with his own charisma and vocation, in an absorbing and almost endless work. This means that, for the rest of our lives, each of us will have to devote time and effort to this task, as hard as it is promising.

[I am going to allow myself a small digression. A great physician, perhaps the greatest that the Anglo-Saxon world has ever given to history, William Osler, was very concerned about the trainingand the human character of his students. Osler told them that, since they did not have the time to acquire the culture of a scholar, they should at least try to attain that of a gentleman, for which he recommended that they should endeavour to reservea few minutes to "commune every day with the greats of humanity", to read the Bible, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Plato and others. I asked them to organise a Library Servicesmade up of 10 titles, minimal in size, but dense with humanity. The digression comes to purposefrom the Evangelium vitae. We must reread it from time to time. We cannot be weary of it or dismiss it as something known or outdated. All the Pope's moral energy is contained there, pent up, to help us in our low hours. We cannot allow the Encyclical's impact to fade with the passage of time and eventually die out]. The paragraph ends.

Let's go back. I said that the culture of life makes each of us feel that human life on earth is a militia. It is logical that the "culture of life" devotes an intense and priority effort to the warlike dimension, antagonistic to the culture of death, all over the world, as rich in fruits as it is poor in means. There is an immense literature of the "culture of life" against the "culture of death", scattered in pamphlets, bulletins, magazines and books published on paper, and a massive amount of information deposited on network24. Much of this literature, despite its polemical character, abounds in good doctrine and understanding for the misguided, and responds to shadows with light, to harshness with tenderness, to pessimism with openness to hope. This literature is enormously diversified, covering the whole imaginable spectrum of tastes and sensibilities. If it is true that variety is the salt and pepper of life, pro-life documentation is not lacking in flavour.

But not always, on the side of the culture of life, actions and thoughts are inspired or written on core topicin the affirmative. The battle in favour of life, I repeat, is hard and relentless. It is against an enemy with enormous means and resources: it is, as the Pope says, a war of the weak against the strong25.

Given the disproportion of forces between the two sides, it is not surprising that, over time, a peculiar ethos developed among many fighters for life. In their actions and writings there are signs of harshness and resentment, harshness and acrimony. It is the almost inevitable resultof fatigue, of wounds, of apparent defeats, typical of any prolonged war. In the urgency of fighting to at least survive, the thought of being in favour of life loses presence and the idea that the decisive thing is to annihilate the enemy is imposed. This generates a mentality that is more negating than affirmative, more demolishing than constructive. Schools for friendship is lost. Sometimes, those who fight for life have their character changed: they become bitter and unattractive.

Paradoxically, what began as an affirmative movement in favour of life has been insensibly transformed into a generator of "anti" actions: against abortion or euthanasia, but also against individuals and powerful organisations behind the "culture of death". In the harshness of the fight, it is not easy to refuse the temptation to use the same violent weapons that the enemy uses. One can even forget that the culture of life is intrinsically affirmative, that, I insist, being intransigent towards error, which it wishes to refute with rationality and patience, it strives to understand everyone generously, because it wants to attract everyone.

It is therefore appropriate to remind all those who fight for life that the culture of life is there, not to weaken or annihilate those who worship death, but to save them, to offer them new signs of hope. The culture of life works to increase justice and solidarity, it seeks to build an authentic civilisation in truth and love26. The culture of life is an essentially affirmative endeavour.

It is easy to understand why, given the violence of this war and the proximity of the battle front, less attention has been devoted to unravelling the positive contents of the new culture of life than to the seemingly more urgent task of combating the errors and strategies of the "culture of death".

And yet, it seems that nothing is more essential and urgent than to study the questions and problems that could be called affirmative aspects of the culture of life.

It's about thinking deeply about things we have pending, about things as interesting as these:

- in defining the psychological tone, constructive and appealing, that the culture of life has to set in its ideas and actions;

- in presenting the culture of life as an ever-fresh novelty, continually renewing itself and adapting to the conditions of place and time;

- The aim is to characterise his intellectual and human style, unitary at its core, but adapted to the multiple variety of mentalities, situations and places, a variety which must not only be respected but encouraged;

- in how to ensure that the messages of the culture of life are always informed by understanding, joy and theological hope, and also by solid science, with a firm commitment to the proven dataof biology and anthropology, truth that it is never legitimate to deny or exaggerate, torture or manipulate;

- on how to explore new ways of expressing human and Christian enthusiasm for human life, without falling into rosy lyricism or Manichean narratives;

- in determining how far good zeal in the defence of life should be taken in order not to fall into incarceration or harassment;

- in how to point out, while respecting the free initiative of all, the opportunity to pursue certain common objectives, i.e. to create a minimum of coordination amidst the necessary polyphony of the culture of life;

- in finding ways to create avenues for Internal Communications, to hear from each other about the thousand ideas we can come up with to spread the culture of life;

- on how to harmoniously amalgamate the rationality of objective moral judgements with the internshipof compassion;

- on how to learn to combine the affirmation of moral truth with a welcome for those who are wrong.

One thing is clear from the Pope's message. Pro-life activism cannot but be affirmative, revealing its evangelical richness. It can no longer fall into the trap of going against the grain, of leaving the field to the opposition and playing counter-attack, of being driven to compete in hatred or haughtiness, as its enemies want.

We must go forward in the world sowing with joy this very human and true doctrine, giving thanks to God who allows us to bring love out of hatred and life out of death. The culture of life has to be built and thought with the financial aidof the reflection of the theologian, the abstraction of the thinker and the researchof the sociologist. But also with personal stories, with poetry and songs that tell the beauty of real life, of the firmness of love. And that they do so with force, not to leave a fleeting impression, a slight stirring of the spirit, but a wound that hurts every day.

How much we have to learn and to do! A few days ago I received this news: a awardcalled Q's, destined to reward the best single of the month, was awarded to 72, a song with a lot of momentum destined to spread the word about the morning-after pill. We could spend many minutes commenting on the news, but I think the main point has been made a long time ago: that the children of darkness are much more awake than the children of light.

The truth is that writing a letter to Nature is much simpler than composing a song and organising a montage to promote it thanks to a very advertising-friendly award. But someone will have to compose pro-life songs.

Conclusion: The new culture of life will have to be something very much like the prodigal son's father's house. All the characters are there. All the ideas are there.

(1) Evangelium vitae, 1.

(2) Evangelium vitae, 45.

(3) Evangelium vitae, 78.

(4) Evangelium vitae, 79.

(5) Evangelium vitae, 83.

(8) Evangelium vitae, 78.

(9) Evangelium vitae, n. 28

(10) Evangelium vitae, nos. 21, 28 (twice), 50, 87, 95, 100.

(11) Evangelium vitae, nn. 6, 82, 92, 95 (three times), 97, 98 (four times), 100. In this second meaning, seven times, culture is described as new; once it is called authentic, and once more true. Four times, it is simply referred to as the culture of life.

(12) Evangelium vitae, 99.

(13) Evangelium vitae, n. 2.

(14) Evangelium vitae, n. 57.

(15) Evangelium vitae, n. 58

(16) Evangelium vitae, n. 70.

(17) Evangelium vitae, n. 77.

(18) Evangelium vitae, n. 95.

(19) Evangelium vitae, no. 98

(20) International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals. Annals of Internal Medicine 1997, 126(1):36-47.

(21) American Medical Association, guideof style. A guide for authors and editors, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1998, Chapter 3, Ethical and legal considerations, pp 87-172.

(22) Roberge L.F., Scientific disinformation, abuse, and neglect within pro-life, Linacre Quarterly 1999, 66(1):56-64.

(23) Connelly R.J., The process of forgiving: an inclusive model, Linacre Quarterly 1999, 66(3):35-44.

(24) See, for example, the website of the Culture of Life Foundation, where one can find links to a large issueof organisations active in the field of the culture of life (link page currently non-existent).

(25) Evangelium vitae, n. 100.

(26) Evangelium vitae, n. 6.