Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Following referendums in 2018 and 2019, the Guatemalan government submitted its report to The Hague in 2020 and the Belizean government has one year to reply.

Guatemala presented its position before the International Court of Justice in The Hague last December, with a half-year delay attributed to the Covid-19 emergency status ; Belize will now have a year to respond. Although the ICJ will then take its time to draft a judgement, it can be said that the territorial dispute between the two neighbours has entered its final stretch, bearing in mind that the dispute over this Central American enclave dates back to the 18th century.

Coats of arms of Guatemala (left) and Belize (right) on their respective flags.

article / Álvaro de Lecea

The territorial conflict between Guatemala and Belize has its roots in the struggle between the Spanish Empire in the Americas and British activity in the Caribbean during the colonial era. The Spanish Crown's inaction in the late 18th century in the face of British encroachment on what is now Belize, then Spanish territory, allowed the British to establish a foothold in Central America and begin exploiting mainland lands for precious woods such as dyewood and mahogany. However, Guatemala's reservations over part of the Belizean land - it claims over 11,000 square kilometres, almost half of the neighbouring country; it also claims the corresponding maritime extension and some cays - generated a status of tension and conflict that has continued to the present day.

In 2008, both countries decided to hold referendums on the possibility of taking the dispute to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which would rule on the division of sovereignty. The Belizeans approved taking that step in 2018 and the Guatemalans the following year. The issue was formalised before the ICJ in The Hague on 12 June 2019.

Historical context

The territory of present-day Belize was colonised by Spain in the mid-16th century as part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain and dependent on the captaincy of Guatemala. However, as there were no mineral resources there and hardly any population, the metropolis paid little attention to the area. This scant Spanish presence favoured pirate attacks, and to prevent them, the Spanish Crown allowed increasing English exploitation in exchange for defence. England carried out a similar penetration on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua, but while the Spanish managed to expel the English from there, they consolidated their settlement at area Belize and finally obtained the territory by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, whereby Spain disengaged itself from this corner of Central America. That concession and another three years later covered just 6,685 square kilometres, a space close to the coast that was later enlarged inland and southward by England, since Spain was not active in the area. From then on the enclave became known as "British Honduras".

The cession did not take into account the claims of the Guatemalans, who considered the space between the Sarstún and Sibún rivers to be their own. Both rivers run west-east, the former forming the border with Guatemala in the south of what is now Belize; the other, further north, runs through the centre of Belize, flowing into the capital, splitting the country in two. However, given the urgency for international recognition when it declared independence in 1821, Guatemala signed several agreements with England, the great power of the day, to ensure the viability of the new state. One of these was the Aycinena-Wyke Treaty (1859), whereby Guatemala accepted Belize's borders in exchange for the construction of a road to improve access from its capital to the Caribbean. However, both sides blamed the other for not complying with the treaty (the road was not built, for example) and Guatemala declared it null and void in 1939.

In the constitution enacted in 1946, Guatemala included the claim in the drafting, and has insisted on this position since the neighbouring country, under the name Belize, gained its independence from the United Kingdom in 1981. As early as 1978, the UN passed a resolution guaranteeing the rights to self-determination and territorial protection of the Belizean people, which also called for a peaceful resolution of the neighbouring conflict. Guatemala did not recognise the existence of the new sovereign state until 1991, and even today still places some limits on Belize's progressive integration into the Central American Integration System. Because of its English background, Belize has historically maintained a closer relationship with the English-speaking Caribbean islands.

Map of Central America and, in detail, the territorial dispute between Guatemala and Belize [Rei-artur / Janitoalevic Bettyreategui].

Adjacency Line and the role of the OAS

Since 2000, the Organisation of American States (OAS), of which both nations are members, has been mediating between the two countries. In the same year, the OAS facilitated a agreement with the goal aim of building confidence and negotiations between the two neighbours. In order to achieve these objectives, the OAS, through its Peace Fund, actively supported the search for a solution by providing technical and political support. Indeed, as a result of this rapprochement, talks on the dispute were resumed and the creation of the "Adjacency Line" was agreed.

This is an imaginary line that basically follows the line that "de facto" separated the two countries from north to south and is where most of the tensions are taking place. Over the years, both sides have increased their military presence there, in response to incidents attributed to the other side. Due to these frequent disputes, in 2015 Belize had to request financial aid military presence from the British navy. It is precisely in the Adjacency Zone that an OAS office is located, whose purpose purpose is to promote contacts between the communities and to verify certain transgressions of the agreements already signed.

One of the most promising developments that took place under the umbrella of the OAS was the signature in 2008 of what was called the "specialagreement between Guatemala and Belize to submit Guatemala's territorial, insular and maritime claim to the International Court of Justice". Under this agreement both countries undertook to submit the acceptance of the Court's mediation to simultaneous popular consultations. However, in 2015, through the protocol of the agreement Special between Belize and Guatemala, these popular consultations were not allowed to take place at the same time. Both parties committed to accept the Court's decision as "decisive and binding" and to comply with and implement it "fully and in good faith".

The Hague and the impact of the future resolution

The referendums were held in 2018 in the case of Guatemala and in 2019 in the case of Belize. Although the percentages of both popular consultations were somewhat mixed, the results were positive. In Belize, the Yes vote won 55.37% of the votes and the No vote 44.63%. In Guatemala, on the other hand, the results were much more favourable for the Yes vote, with 95.88% of the votes, compared to 4.12% for the No vote.

These results show how the Belizeans are wary of resorting to the Hague's decision because, although by fixing final the border they will forever close any claim, they risk losing part of their territory. On the other hand, the prospect of gain is greater in the Guatemalan case, since if its proposal is accepted - or at least part of it - it would strategically expand its access to the Caribbean, now somewhat limited, and in the event of losing, it would simply remain as it has been until now, which is not a serious problem for the country.

The definition of a clear and respected border is necessary at this stage. The adjacent line, observed by the OAS peace and security mission statement , has been successful in limiting tensions between the two countries, but the reality is that certain incidents continue to take place in this unprotected area. These incidents, such as the assassination of citizens of both countries or mistreatment attributed to the Guatemalan military, cause the conflict to drag on and tensions to rise. On the other hand, the lack of a clear definition of borders facilitates drug trafficking and smuggling.

This conflict has also affected Belize's economic and trade relations with its regional neighbours, especially Mexico and Honduras. This is not only due to the lack of land boundaries, but also to the lack of maritime boundaries. This area is very rich in natural resources and has the second largest coral reef reservation in the world, after Australia. This has, unsurprisingly, affected bilateral relations between the two countries. Whilst regional organisations are calling for greater regional integration, the tensions between Belize and Guatemala are preventing any improvement in this regard.

The Guatemalan president has stated that, regardless of the Court's result , he intends to strengthen bilateral relations, especially in areas such as trade and tourism, with neighbouring Belize. For their part, the Caricom heads of state expressed their support for Belize in October 2020, their enthusiasm for the ICJ's intervention and their congratulations to the OAS for its mediation work.

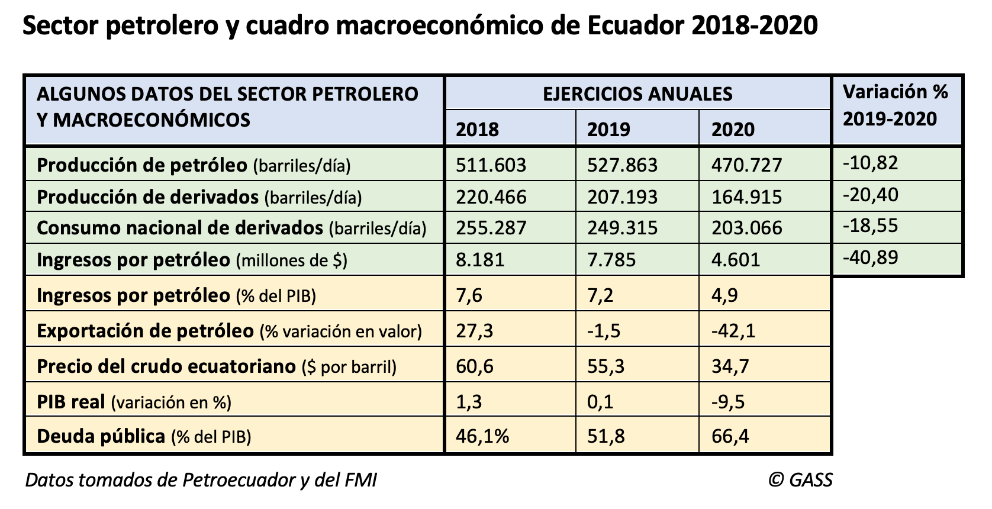

The country left the cartel in order to expand pumping, but the Covid-19 crisis has cut extraction volumes by 10.8%.

Construction of a variant of the oil pipeline that crosses the Andes, from the Ecuadorian Amazon to the Pacific [Petroecuador].

ANALYSIS / Jack Acrich and Alejandro Haro

Ecuador left the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) on 1 January 2020 to avoid having to continue to join the production cuts imposed by group , which it agrees to in order to push up the world price of crude oil. Ecuador preferred to sell more barrels, albeit at a lower price, because by exporting more at the end of the day written request it could increase its income and thus get out of its serious financial situation status , which the coronavirus emergency has only accentuated, with a fall in GDP in 2020 currently estimated at 9.5 per cent.

However, domestic economic difficulties and the difficult international situation have not only prevented Ecuador from expanding pumping, but oil production has fallen by 10.8% in the last year. average In 2020, Ecuador extracted 472,000 barrels of oil per day, especially affected by the sharp reduction in activity in April with the beginning of the confinement, which was not compensated for the rest of the year. agreement This is a volume that is below the 500,000 line that has always been exceeded in recent years (in 2019 production was 528,000), according to figures from Petroecuador, the state hydrocarbons company. The reduction in global consumption during the Covid-19 year also correlated with a drop in the consumption of derivatives in Ecuador, especially gasoline and diesel, which fell by 18.5%.

International investment constrained by the pandemic context and reduced consumption marked a status that could hardly lead to an increase in production. In 2020, Ecuador saw a drop in the value of oil exports of 42.1% (twice as much as total exports), which, combined with a deterioration in the price of a barrel of oil, meant a 40.9% reduction in public revenue from the oil sector, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) data .

The figures for the first two months of 2021 indicate an accentuation of the fall in crude oil production (-4.73% compared to January and February 2020) and derivatives (-7.47%), as well as their export (-22.8%).

Cutting expense and seeking oil revenues

Exiting OPEC did not pose any particular risk for Ecuador, which had already left the organisation in a previous period. Its limited weight in OPEC and the progressive decline in the cartel's own strength meant that Ecuador's attempt to go it alone was not particularly costly. The absolute priority of Lenín Moreno's government was to rebalance the country's macroeconomic picture - battered by the high public expense of his predecessor, Rafael Correa - and for this it urgently needed to increase state revenue, a significant part of which in Ecuador normally comes from the hydrocarbons sector.

When he became president in 2017, Moreno set out to steer the country towards more market-friendly energy policies. The president was determined to break with the nationalist approach of his predecessor, whose policies discouraged foreign investment in the oil industry while significantly increasing public debt. Among the most costly programmes undertaken by Correa was to maintain high subsidies for energy consumption, with especially low fuel prices.

In order to overcome the financial status that Ecuador found itself in when he took office, Moreno approached the IMF to apply for financial aid financial, and committed to structural reforms, including the gradual dismantling of subsidies. These reforms, however, were not well received and the social unrest that spread throughout the country put further pressure on the oil industry.

In February 2019, Moreno negotiated an IMF loan to help reduce the country's large fiscal deficit and huge external debt, which by the end of 2018 had reached 46.1 per cent of GDP and twelve months later would reach 51.8 per cent. The committed 'bailout' was for $10.2 billion, of which $6.5 billion came from the IMF and the rest from other international agencies.

As part of austerity measures agreed with the IMF, Moreno was forced to end government subsidies that had kept petrol prices low for decades. In early October 2019 he announced a plan of cuts to save $2.27 billion a year, essentially withdrawing the fuel subsidy. The advertisement decree, which would later be annulled, immediately provoked massive protests, both from transporters and low-income sectors, as well as most notably from indigenous communities. The street violence forced the president to leave Quito for a few days and move to Guayaquil.

To address the need for revenue, Moreno sought to rely on the oil industry, which accounts for roughly a third of the country's total exports. He initially expressed the intention to seek a rise from the 545,000 barrels of crude oil produced at the time to almost 700,000 barrels a day.

goal One of the measures taken in this direction was to promote the development and the exploitation of the Ishpingo-Tiputini-Tambococha field, with the aim of increasing oil production by 90,000 barrels a day. This decision met with social rejection due to the environmental damage it could cause, as the Yasuní National Park, in the Ecuadorian Amazon, has been declared a protected area. The government then decided to postpone the expansion of production, first to 2021 and then to 2022. The civil service examination was especially led by indigenous communities, in a mobilisation that partly explains the success in the 2021 presidential elections of Yaku Pérez's indigenist Pachakutik movement, which almost made it to the second round.

Another measure was to reverse some of his predecessor's emblematic policies. For example, he eliminated the service contracts introduced under President Correa, thus restoring the model production-sharing contract. This reform was more favourable to international oil companies, as it allowed them to retain a share of oil reserves; it also offered them financial incentives to invest in the country. The new model was first applied in the tenders awarded during the twelfth Intracampos oil round, in the Oriente region, which is rich in oil reserves. Under this contract modality , the Moreno administration awarded seven of the eight exploration blocks on offer with a total investment of more than $1.17 billion.

Fall in production

Due to the urgency of increasing revenues, Ecuador resisted the plan of production cuts that OPEC has been imposing on its members at various times since the abrupt fall in oil prices in 2014. Initially, the organisation accepted that some of its members, with moderate or very low production volumes compared to previous figures, as was the case of Venezuela, would maintain their extraction rates. But since it could no longer be an exception, Ecuador preferred to announce at the end of 2019 that it would leave OPEC and not have to reduce its production to 508,000 barrels per day in 2020, which was the quota set for it.

What is striking is that last year production finally fell from 528,000 barrels per day in 2019 to 472,000 (a drop of 10.8%), and not because of decisions taken at OPEC headquarters in Vienna but because of the various difficulties subject caused by the Covid-19 crisis. Petroecuador's oil exports fell from 331,321 barrels per day in 2019 to 316,000, a drop of 4.6%, which in monetary terms was greater, as the price of a barrel of Ecuadorian mixed oil fell from 55.3 dollars in 2019 to 34.7 in 2020.

One element that makes it difficult for Ecuador to take better advantage of its hydrocarbon potential is that it has insufficient infrastructure for refining crude oil. The country has three refineries, but their capacity does not reach the volume of domestic consumption of oil derivatives, which means that it must import diesel, naphtha and other products. This means that in times of high oil prices, Ecuador benefits from exports, but also has to pay a higher invoice price for imports of derivatives. In 2020, Petroecuador had to import 137,300 barrels per day.

The complicated situation caused by the pandemic has continued to put pressure on Ecuador's public debt, which reached 66.4% at the end of 2020, despite all the attempts made by the Moreno government to reduce it.

The next president, due to take office at the end of May 2021, will also have little room for manoeuvre due to these debt volumes and will have to continue to rely on higher oil revenues to balance public finances. The expansionary policies of expense during Correa's presidency took place in the context of the commodity super-cycle, which benefited South America so much, but this is unlikely to be repeated in the short term deadline.

OPEC's loss of weight

With its departure from OPEC, Ecuador left an international organisation that was created in 1960 with the aim of regulating the world oil market and controlling oil prices to a certain extent. goal . The founding members were Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. Over time, other countries joined OPEC and today it is made up of thirteen members: Algeria, Angola, Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Libya, Nigeria, United Arab Emirates and the five founding countries. When it was created, the organisation sought to establish, acting as a cartel, a kind of counterweight to a series of Western energy transnationals, mainly from the United States and the United Kingdom. OPEC members account for about 40 per cent of world oil production and contain about 80 per cent of the world's proven oil reserves. To be admitted as a member of the organisation it is necessary to have substantial oil exports and to share those of the member countries.

Ecuador joined OPEC in 1973, but suspended its membership in 1992. Subsequently, in 2007 it resumed active participation until its leave in January 2020. Considering that Ecuador was one of OPEC's smaller members, it did not really have much influence in the organisation and its exit does not represent a substantial loss for the organisation. However, it is a second departure in just one year, as Qatar, which had more weight in the cartel, left on 1 January 2019. In its case, its divorce from OPEC was due to other reasons, such as its tensions with Saudi Arabia and its desire to focus on the gas sector, of which it is one of the world's largest producers.

These moves are an example of OPEC's loss of influence. This has led it to establish alliances with producers that are not part of the organisation, such as Russia and some other countries forming OPEC+. With the decline of oil production in Venezuela and the decreasing ability of other members to control their production and exports, Saudi Arabia has been increasingly consolidating its position as the cartel's leader, accounting for around a third of the total production, with approximately 9.4 million barrels per day. In a way, Saudi Arabia and Russia remain, in a head to head battle, as the main countries seeking to cut production in an attempt to increase prices. Additionally, thanks to fracking, the United States has become the largest oil producer, representing a major influence on the international crude oil market, affecting the power that OPEC may have.

Detainee in a Xinjiang re-education camp located in Lop County listening to "de-radicalization" talks [Baidu baijiahao].

Detainee in a Xinjiang re-education camp located in Lop County listening to "de-radicalization" talks [Baidu baijiahao].

ESSAY / Rut Noboa

Over the last few years, reports of human rights violations against Uyghur Muslims, such as extrajudicial detentions, torture, and forced labor, have been increasingly reported in the Xinjiang province's so-called "re-education" camps. However, the implications of the Chinese undertakings on the province's ethnic minority are not only humanitarian, having direct links to China's ongoing economic projects, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and natural resource extraction in the region. Asides from China's economic diary, ongoing projects in Xinjiang appear to prototype future Chinese initiatives in terms of expanding the surveillance state, particularly within the scope of technology. When it comes to other international actors, the Xinjiang dispute has evidenced a growing diplomatic split between countries against it, mostly western liberal democracies, and countries willing to at least defend it, mostly countries with important ties to China and dubious human rights records. The issue also has important repercussions for multinational companies, with supply chains of well-known international companies such as Nike and Apple benefitting from forced Uyghur labour. The situation in Xinjiang is critically worrisome when it comes to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly considering recent outbreaks in Kashgar, how highly congested these "reeducation" camps, and potential censorship from the government. Finally, Uyghur communities continue to be an important factor within this conversation, not only as victims of China's policies but also as dissidents shaping international opinion around the matter.

The Belt and Road Initiative

Firstly, understanding Xinjiang's role in China's ongoing projects requires a strong geographical perspective. The northwestern province borders Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India, giving it important contact with other regional players.

This also places it at the very heart of the BRI. With it setting up the twenty-first century "Silk Road" and connecting all of Eurasia, both politically and economically, with China, it is no surprise that it has managed to establish itself as China's biggest infrastructural project and quite possibly the most important undertaking in Chinese policy today. Through more and more ambitious efforts, China has established novel and expansive connections throughout its newfound spheres of influence. From negotiations with Pakistan and the establishment of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) securing one of the most important routes in the initiative to Sri Lanka defaulting on its loan and giving China control over the Hambantota Port, the Chinese government has managed to establish consistent access to major trade routes.

However, one important issue remains: controlling its access to Central Asia. One of the BRI's initiative's key logistical hubs is Xinjiang, where the Uyghurs pose an important challenge to the Chinese government. The Uyghur community's attachment to its traditional lands and culture is an important risk to the effective implementation of the BRI in Xinjiang. This perception is exacerbated by existing insurrectionist groups such as the East Turkestan independence movement and previous events in Chinese history, including the existence of an independent Uyghur state in the early 20th century[1]. Chinese infrastructure projects that cross through the Xinjiang province, such as the Central Asian High-speed Rail are a priority that cannot be threatened by instability in the region, inspiring the recent "reeducation" and "de-extremification" policies.

Natural resource exploitation

Another factor for China's growing control over the region is the fact that Xinjiang is its most important energy-producing region, even reaching the point where key pipeline projects connect the northwestern province with China's key coastal cities and approximately 60% of the province's gross regional production comes from oil and natural gas extraction and related industries[2]. With China's energy consumption being on a constant rise[3] as a result of its growing economy, control over Xinjiang is key to Chinese.

Additionally, even though oil and natural gas are the region's main industries, the Chinese government has also heavily promoted the industrial-scale production of cotton, serving as an important connection with multinational textile-based corporations seeking cheap labour for their products.

This issue not only serves as an important reason for China to control the Uyghurs but also promotes instability in the region. The increased immigration from a largely Han Chinese workforce, perceived unequal distribution of revenue to Han-dominated firms, and increased environmental costs of resource exploitation have exacerbated the pre-existing ethnic conflict.

A growing diplomatic split

The situation in Xinjiang also has important implications for international perceptions of Chinese propaganda. China's actions have received noticeable backlash from several states, with 22 states issuing a joint statement to the Human Rights Council on the treatment of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang on July 8, 2019. These states called upon China "to uphold its national laws and international obligations and to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms".

Meanwhile, on July 12, 2019, 50 (originally 37) other states issued a competing letter to the same institution, commending "China's remarkable achievements in the field of human rights", stating that people in Xinjiang "enjoy a stronger sense of happiness, fulfillment and security".

This diplomatic split represents an important and growing division in world politics. When we look at the signatories of the initial letter, it is clear to see that all are developed democracies and most (except for Japan) are Western. Meanwhile, those countries that chose to align themselves with China represent a much more heterogeneous group with states from the Middle East, Asia, and Africa[4]. Many of these have questionable human rights records and/or receive important funding and investment from the Chinese government, reflecting both the creation of an alternative bloc distanced from Western political influence as well as an erosion of preexisting human rights standards.

China's Muslim-majority allies: A Pakistani case study

The diplomatic consequences of the Xinjiang controversy are not only limited to this growing split, also affecting the political rhetoric of individual countries. In the last years, Pakistan has grown to become one of China's most important allies, particularly within the context of CPEC being quite possibly one of the most important components of the BRI.

As a Muslim-majority country, Pakistan has traditionally placed pan-Islamic causes, such as the situations in Palestine and Kashmir, at the centre of its foreign policy. However, Pakistan's position on Xinjiang appears not just subdued but even complicit, never openly criticising the situation and even being part of the mentioned letter in support of the Chinese government (alongside other Muslim-majority states such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE). With Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan addressing the General Assembly in September 2019 on Islamophobia in post-9/11 Western countries as well as in Kashmir but conveniently omitting Uyghurs in Xinjiang[5], Pakistani international rhetoric weakens itself constantly. Due to relying on China for political and economic support, it appears that Pakistan will have to censor itself on these issues, something that also rings true for many other Muslim-majority countries.

Central Asia: complacent and supportive

Another interesting case study within this diplomatic split is the position of different countries in the Central Asian region. These states - Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan - have the closest cultural ties to the Uyghur population. However, their foreign policy hasn't been particularly supportive of this ethnic group with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan avoiding the spotlight and not participating in the UNHRC dispute and Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan being signatories of the second letter, explicitly supporting China. These two postures can be analyzed through the examples of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Kazakhstan has taken a mostly ambiguous position to the situation. Having the largest Uyghur population outside China and considering Kazakhs also face important persecution from Chinese policies that discriminate against minority ethnic groups in favour of Han Chinese citizens, Kazakhstan is quite possibly one of the states most affected by the situation in Xinjiang. However, in the last decades, Kazakhstan has become increasingly economically and, thus, politically dependent on China. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan implemented what some would refer to as a "multi-vector" approach, seeking to balance its economic engagements with different actors such as Russia, the United States, European countries, and China. However, with American and European interests in Kazakhstan decreasing over time and China developing more and more ambitious foreign policy within the framework of strategies such as the Belt and Road Initiative, the Central Asian state has become intimately tied to China, leading to its deafening silence on Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

A different argument could be made for Uzbekistan. Even though there is no official statistical data on the Uyghur population living in Uzbekistan and former president Islam Karimov openly stated that no Uyghurs were living there, this is highly questionable due to the existing government censorship in the country. Also, the role of Uyghurs in Uzbekistan is difficult to determine due to a strong process of cultural and political assimilation, particularly in the post-Soviet Uzbekistan. By signing the letter to the UNHCR in favour of China's practices, the country has chosen a more robust support of its policies.

All in all, the countries in Central Asia appear to have chosen to tolerate and even support Chinese policies, sacrificing cultural values for political and economic stability.

Forced labour, the role of companies, and growing backlash

In what appears to be a second stage in China's "de-extremification" policies, government officials have claimed that the "trainees "in its facilities have "graduated", being transferred to factories outside of the province. China claims these labor transfers (which it refers to as vocational training) to be part of its "Xinjiang Aid" central policy[6]. Nevertheless, human rights groups and researchers have become growingly concerned over their labor standards, particularly considering statements from Uyghur workers who have left China describing the close surveillance from personnel and constant fear of being sent back to detention camps.

Within this context, numerous companies (both Chinese and foreign) with supply chain connections with factories linked to forced Uyghur labour have become entangled in growing international controversies, ranging from sportswear producers like Nike, Adidas, Puma, and Fila to fashion brands like H&M, Zara, and Tommy Hilfiger to even tech players such as Apple, Sony, Samsung, and Xiaomi[7]. Choosing whether to terminate relationships with these factories is a complex choice for these companies, having to either lose important components of their intricate supply chains or face growing backlash on an increasingly controversial issue.

The allegations have been taken seriously by these groups with organizations such as the Human Rights Watch calling upon concerned governments to take action within the international stage, specifically through the United Nations Human Rights Council and by imposing targeted sanctions at responsible senior officials. Another important voice is the Coalition to End Forced Labour in the Uyghur Region, a coalition of civil society organizations and trade unions such as the Human Rights Watch, the Investor Alliance for Human Rights, the World Uyghur Congress, and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, pressuring the brands and retailers involved to exclude Xinjiang from all components of the supply chain, especially when it comes to textiles, yarn or cotton as well as calling upon governments to adopt legislation that requires human rights due diligence in supply chains. Additionally, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, the same organisation that carried out the initial report on forced Uyghur labor and surveillance beyond Xinjiang and within the context of these labor transfers, recently created the Xinjiang Data Project. This initiative documents ongoing Chinese policies on the Uyghur community with open-source data such as satellite imaging and official statistics and could be decidedly useful for human rights defenders and researchers focused on the topic.

One important issue when it comes to the labour conditions faced by Uyghurs in China comes from the failures of the auditing and certification industry. To respond to the concerns faced by having Xinjiang-based suppliers, many companies have turned to auditors. However, with at least five international auditors publicly stating that they would not carry out labor-audit or inspection services in the province due to the difficulty of working with the high levels of government censorship and monitoring, multinational companies have found it difficult to address these issues[8]. Additionally, we must consider that auditing firms could be inspecting factories that in other contexts are their clients, adding to the industry's criticism. These complaints have led human rights groups to argue that overarching reform will be crucial for the social auditing industry to effectively address issues such as excessive working hours, unsafe labor conditions, physical abuse, and more[9].

Xinjiang: a prototype for the surveillance state

From QR codes to the collection of biometric data, Xinjiang has rapidly become the lab rat for China's surveillance state, especially when it comes to technology's role in the issue.

One interesting area being massively affected by this is travel. As of September 2016, passport applicants in Xinjiang are required to submit a DNA sample, a voice recording, a 3D image of themselves, and their fingerprints, much harsher requirements than citizens in other regions. Later in 2016, Public Security Bureaus across Xinjiang issued a massive recall of passports for an "annual review" followed by police "safekeeping"[10].

Another example of how a technologically aided surveillance state is developing in Xinjiang is the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), a big data program for policing that selects individuals for possible detention based on specific criteria. According to the Human Rights Watch, which analyzed two leaked lists of detainees and first reported on the policing program in early 2018, the majority of people identified by the program are being persecuted because of lawful activities, such as reciting the Quran and travelling to "sensitive" countries such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Additionally, some criteria for detention appear to be intentionally vague, including "being generally untrustworthy" and "having complex social ties"[11].

Xinjiang's case is particularly relevant when it comes to other Chinese initiatives, such as the Social Credit System, with initial measures in Xinjiang potentially aiding to finetune the details of an evolving surveillance state in the rest of China.

Uyghur internment camps and COVID-19

The implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Uyghurs in Xinjiang are pressing issues, particularly due to the virus's rapid spread in highly congested areas such as these "reeducation" camps.

Currently, Kashgar, one of Xinjiang's prefectures is facing China's most recent coronavirus outbreak[12]. Information from the Chinese government points towards a limited outbreak that is being efficiently controlled by state authorities. However, the authenticity of this data is highly controversial within the context of China's early handling of the pandemic and reliance on government censorship.

Additionally, the pandemic has more consequences for Uyghurs than the virus itself. As the pandemic gives governments further leeway to limit rights such as the right to assembly, right to protest, and freedom of movement, the Chinese government gains increased lines of action in Xinjiang.

Uyghur communities abroad

The situation for Uyghurs living abroad is far from simple. Police harassment of Uyghur immigrants is quite common, particularly through the manipulation and coercion of their family members still living in China. These threatening messages requesting staff information or pressuring dissidents abroad to remain silent. The officials rarely identify themselves and in some cases these calls or messages don't necessarily even come from government authorities, instead coming from coerced family members and friends[13]. One interesting case was reported in August 2018 by US news publication The Daily Beast in which an unidentified Uyghur American woman was asked by her mother to send over pictures of her US license plate number, her phone number, her bank account number, and her ID card under the excuse that China was creating a new ID system for all Chinese citizens, even those living abroad[14]. A similar situation was reported by Foreign Policy when it came to Uyghurs in France who have been asked to send over home, school, and work addresses, French or Chinese IDs, and marriage certificates if they were married in France[15].

Regardless of Chinese efforts to censor Uyghur dissidents abroad, their nonconformity has only grown with the strengthening of Uyghur repression in mainland China. Important international human rights groups such as Amnesty International and the Human Rights Watch have been constantly addressing the crisis while autonomous Uyghur human rights groups, such as the Uyghur Human Rights Project, the Uyghur American Association, and the Uyghur World Congress, have developed from communities overseas. Asides from heavily protesting policies such as the internment camps and increasing surveillance in Xinjiang, these groups have had an important role when it comes to documenting the experiences of Uyghur immigrants. However, reports from both human rights group and average agencies when it comes to the crisis have been met with staunch rejection from China. One such case is the BBC being banned in China after recently reporting on Xinjiang internment camps, leading it to be accused of not being "factual and fair" by the China National Radio and Television Administration. The UK's Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab referred to the actions taken by the state authorities as "an unacceptable curtailing of average freedom" and stated that they would only continue to damage China's international reputation[16].

One should also think prospectively when it comes to Uyghur communities abroad. As seen in the diplomatic split between countries against China's policies in Xinjiang and those who support them (or, at the very least, are willing to tolerate them for their political interest), a growing number of countries can excuse China's treatment of Uyghur communities. This could eventually lead to countries permitting or perhaps even facilitating China's attempts at coercing Uyghur immigrants, an important prospect when it comes to countries within the BRI and especially those with an important Uyghur population, such as the previously mentioned example of Kazakhstan.

REFERENCES

[1] Qian, Jingyuan. 2019. "Ethnic Conflicts and the Rise of Anti-Muslim Sentiment in Modern China." Department of Political Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3450176.

[2] Cao, Xun, Haiyan Duan, Chuyu Liu, James A. Piazza, and Yingjie Wei. 2018. "Digging the "Ethnic Violence in China" Database: The Effects of Inter-Ethnic Inequality and Natural Resources Exploitation in Xinjiang." The China Review (The Chinese University of Hong Kong) 18 (No. 2 SPECIAL THEMED SECTION: Frontiers and Ethnic Groups in China): 121-154. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26435650

[3] International Energy Agency. 2020. Data & Statistics - IEA. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics?country=CHINA&fuel=Energy%20consumption&indicator=TotElecCons.

[4] Yellinek, Roie, and Elizabeth Chen. 2019. "The "22 vs. 50" Diplomatic Split Between the West and China." China Brief (The Jamestown Foundation) 19 (No. 22): 20-25. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://jamestown.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Read-the-12-31-2019-CB-Issue-in-PDF.pdf?x91188.

[5] United Nations General Assembly. 2019. "General Assembly official records, 74th session : 9th plenary meeting." New York. Accessed October 18, 2020.

[6] Xu, Vicky Xiuzhong, Danielle Cave, James Leibold, Kelsey Munro, and Nathan Ruser. 2020. "Uyghurs for sale: 'Re-education', forced labour and surveillance beyond Xinjiang." Policy Brief, International Cyber Policy Centre, Australian Strategic Policy Paper. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/uyghurs-sale

[7] Ibid.

[8] Xiao, Eva. 2020. Auditors to Stop Inspecting Factories in China's Xinjiang Despite Forced-Labor Concerns. 21 September. Accessed December 2020, 16. https://www.wsj.com/articles/auditors-say-they-no-longer-will-inspect-labor-conditions-at-xinjiang-factories-11600697706.

[9] Kashyap, Aruna. 2020. Social Audit Reforms and the Labor Rights Ruse. 7 October. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/07/social-audit-reforms-and-labor-rights-ruse.

[10] Human Rights Watch. 2016. China: Passports Arbitrarily Recalled in Xinjiang. 21 November. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/11/22/china-passports-arbitrarily-recalled-xinjiang

[11] Human Rights Watch. 2020. China: Big Data Program Targets Xinjiang's Muslims. 9 December. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/09/china-big-data-program-targets-xinjiangs-muslims.

[12] National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. 2020. How China's Xinjiang is tackling new COVID-19 outbreak. 29 October. Accessed November 14, 2020. http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2020-10/29/c_81994.htm.

[13] Uyghur Human Rights Project. 2019. "Repression Across Borders: The CCP's Illegal Harassment and Coercion of Uyghur Americans."

[14] Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany. 2018. Chinese Cops Now Spying on American Soil. 14 August. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://www.thedailybeast.com/chinese-police-are-spying-on-uighurson-american-soil.

[15] Allen-Ebrahimian. 2018. Chinese Police Are Demanding staff Information From Uighurs in France. 2 March. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/03/02/chinese-police-are-secretly-demanding-staff-information-from-french-citizens-uighurs-xinjiang/.

[16] Reuters Staff. 2021. BBC World News barred in mainland China, radio dropped by HK public broadcaster. 11 February. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-britain-bbc/bbc-world-news-barred-from-airing-in-china-idUSKBN2AB214.

review / Emili J. Blasco

The discipline of "political risk" can be conceived in a restrictive way, as usual, referring to the prospective analysis of disruptions that, by states and governments, can affect political and social stability and the regulatory framework and, therefore, the interests of investors, companies and economic sectors. This conception, which globalisation also leads to call "geopolitical risk", is only a part - in fact, the minor part - of Nigel Gould-Davies' approach, who by putting the adjective "global" in the degree scroll of his book is referring to a conceptually more general political risk, merged with fields such as corporate reputation, public affairs and business diplomacy.

The author claims that the relationship with the environment is essential for a business and calls for a company's management to always have someone manager of engagement (which we could translate as involvement, commitment, participation or partnership): an engager who has the same level of authority as the engineer who knows how to manufacture the product and the salesperson who knows how to monetise it; someone specialised in "persuading" external actors - governments and civil society groups - of the company's goodness, creating "alignments" that are beneficial for business. Engagement at both the national and international level, if the activity or interests go beyond one's own borders, giving rise to "corporate diplomacy", as the current "increase in political risks means that a company needs a foreign policy".

Gould-Davies sees these more political issues not as an "impertinent intrusion" into markets, but as something endogenous to them. So the business, in addition to attending to production and marketing issues, must also pay equal attention to a third dimension: engagement with political and social actors to avoid or overcome risks that it faces in that external sphere. This is "a third activity and a third role to carry it out: a new political piece in the mechanism of value creation".

The author emphasises management on the present and the very short term future deadline, and downplays the importance of short and medium term prospective analysis deadline which has been the preserve of political risk analysts. He complains that the latter have paid "too much attention to prediction, with its frequent disappointments, and too little to engagement"; " engagement, on the other hand, requires relatively little prediction beyond the short deadline". "There is a lot of unbalanced political risk activity, producing a lot of analysis and prediction, but much less guidance on what to do".

Moreover, unlike the usual political risk analysis, which is more focused on the actions of states or governments, the concept the author uses extends very specifically to the pressures that can arise from civil society. "The new political risks emerge from non-state social forces: consumers, investors, public opinion, civil society, local communities and the media. They do not seek to challenge ownership or rights to use productive assets. They do not seek to destroy, take or block. Their focus is narrower: they usually seek to regulate the terms on which production and trade take place (...) Their motive is usually an ethical commitment to justice and equity. Their goal is to mitigate the wider adverse impacts of corporate activity on others; they are selfless rather than self-serving".

Gould-Davies notes that while previously the norm was government threats in development or emerging countries with less stable societies and unconsolidated rule of law, today pressures on business are increasing in developed nations. "The likelihood of major conflict and de-globalisation is increasing, but more importantly, its impact is shifting towards the developed world," he writes. Moreover, the fact that there is less and less social peace in Western countries is an increasingly disturbing element: "Sustained civil violence in a highly developed country is no longer a black swan, but a grey swan: improbable but conceivable; possible to define, but impossible to predict".

By focusing on management in the present and characterising the activity as engagement, which is in itself very communication-centred, Gould-Davis stretches the classical concept of political risk, which has been more oriented towards analysis and foresight, too far. In doing so, he treads on activities that are becoming widely known development for their own sake, such as corporate communication and reputation or influencing regulatory issues through lobbying or public affairs management functions.

The hydrocarbon field is the centrepiece of President Alberto Fernández's 2020-2023 Gas Plan, which subsidises part of the investment.

Activity of YPF, Argentina's state-owned hydrocarbon company [YPF].

ANALYSIS / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa

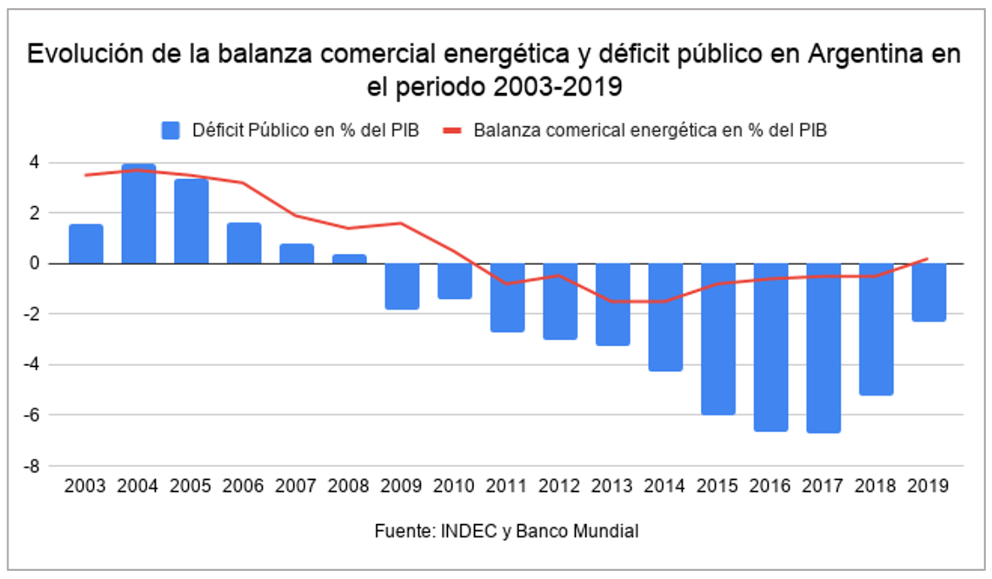

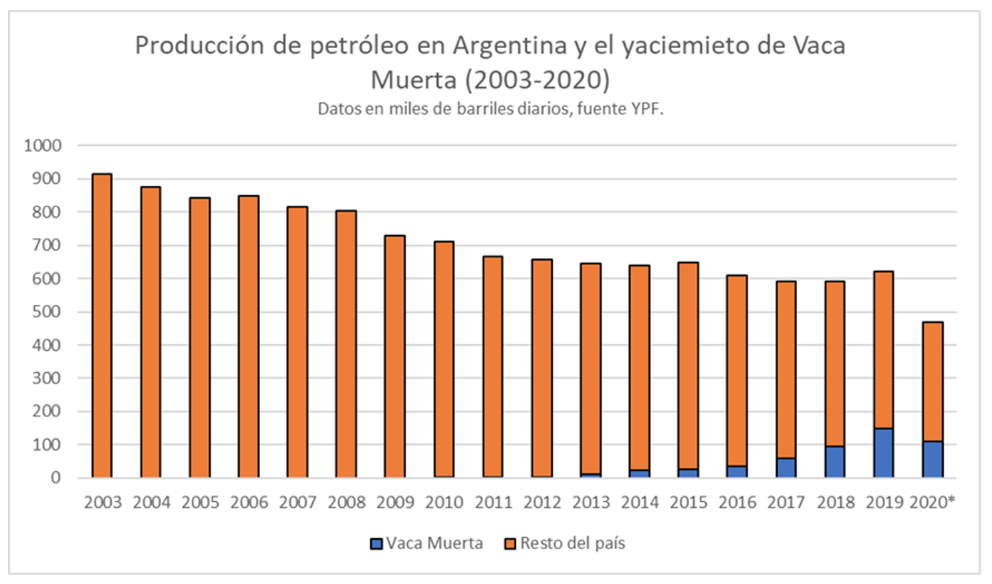

Argentina is facing a deep economic crisis that is having a severe impact on the standard of living of its citizens. The country, which had managed to emerge with enormous sacrifices from the corralito of 2001, sees its leaders committing the same macroeconomic recklessness that led the national Economics to collapse. After a hugely disappointing mandate by Mauricio Macri and his economic "gradualism", the new administration of Alberto Fernández has inherited a very delicate status , now aggravated by the global and national crisis generated by Covid-19. Public debt is now almost 100% of GDP, the Argentine peso is worth less than 90 units to the US dollar, while the public deficit persists. The Economics is still in recession, accumulating four years of decline. The IMF, which lent nearly $44 billion to Argentina in 2018 in the largest loan in the institution's history, has begun to lose patience with the lack of structural reforms and hints of debt restructuring by the government. In this critical status , Argentines are looking to the development unconventional oil industry as a possible way out of the economic crisis. In particular, the Vaca Muerta super field has been the focus of attention of international investors, government and citizens for the last decade, being a very promising project not Exempt of environmental and technical challenges.

The energy sector in Argentina: a history of fluctuations

The oil sector in Argentina has more than 100 years of history since oil was discovered in the Patagonian desert in 1907. The geographical difficulties of area - lack of water, distance from Buenos Aires and salty winds of more than 100 km/h - meant that project advanced very slowly until the outbreak of the First World War. The European conflict interrupted coal imports from England, which until then had accounted for 95% of Argentina's energy consumption. business The emergence of oil in the inter-war period as a strategic raw subject commodity revalued the sector, which began to receive huge foreign and domestic investment in the 1920s. By 1921, YPF, the first state-owned oil company in Latin America, was created, with energy self-sufficiency as its main goal goal. The country's political upheaval during the so-called Década Infame (1930-43) and the effects of the Great Depression damaged the incipient oil sector. The years of Perón's government saw a timid take-off of the oil industry with the opening of the sector to foreign companies and the construction of the first oil pipelines. In 1958, Arturo Frondizi became President of Argentina and sanctioned the Hydrocarbons Law of 1958, achieving an impressive development of the sector in only 4 years with an immense policy of public and private investment that multiplied oil production threefold, extended the network of gas pipelines and generalised access to natural gas for industry and households. The oil regime in Argentina kept the ownership of resource in the hands of the state, but allowed the participation of private and foreign companies in the production process.

Since the successful 1960s in subject oil, the sector entered a period of relative stagnation in parallel with Argentina's chaotic politics and Economics at the time. The 1970s was a complex journey in the desert for YPF, mired in huge debt and unable to increase production and secure the longed-for self-sufficiency.

The so-called Washington Consensus and the arrival of Carlos Menem to the presidency in 1990 saw the privatisation of YPF and the fragmentation of the state monopoly over the sector. By 1998, YPF was fully privatised under the ownership of Repsol, which controlled 97.5% of its capital. It was in the period 1996-2003 that peak oil production was reached, exporting natural gas to Chile, Brazil and Uruguay, and exceeding 300,000 barrels of crude oil per day in net exports.

However, a turnaround soon began in the face of state intervention in the market. Domestic consumption with fixed sales prices for oil producers was less attractive than the export market, encouraging private companies to overproduce in order to export oil and increase revenues exponentially. With the rise in oil prices of the so-called "commodity super-cycle" during the first decade of this century, the price differential between exports and domestic sales widened, creating a real incentive to focus on production. Exploration was thus left in the background, as domestic consumption grew rapidly due to tax incentives and a near horizon was foreseen without the possibility of exports and, therefore, lower income from the increase in reserves.

The exit from the 2001 crisis took place in a context of fiscal and trade surpluses, which allowed the country to regain the confidence of international creditors and reduce the volume of public debt. It was precisely the energy sector that was the main driver of this recovery, accounting for more than half of the trade surplus in the period 2004-2006 and one of Argentina's main sources of fiscal revenue. However, as mentioned above, this production was not sustainable due to the existence of a fiscal framework that distorted oil companies' incentives in favour of immediate consumption without investing in exploration. By 2004, a new tariff was applied to crude oil exports that floated on the basis of the international price of crude, reaching 45% if the price was above 45 dollars. The excessively rentier approach of Néstor Kirchner's presidency ended up dilapidating the sector's investment incentives, although it is true that they allowed for a spectacular increase in derived fiscal revenues, boosting Argentina's generous social and debt repayment plans. sample As a good illustration of this decline in exploration, in the 1980s more than 100 exploratory wells were drilled annually, in 1990 the figure exceeded 90, and by 2010 the figure was 26 wells per year. This figure is particularly dramatic if one takes into account the dynamics that the oil and gas sector tends to follow, with large investments in exploration and infrastructure in times of high prices, as was the case between 2001-2014.

In 2011, after a decade of debate on the oil sector in Argentina, President Cristina Fernández decided to expropriate 51 per cent of the shares of YPF held by Repsol, citing reasons of energy sovereignty and the decline of the sector. This decision followed the line taken by Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales in 2006 to increase the state's weight in the hydrocarbons sector at a time of electoral success for the Latin American left. The expropriation took place in the same year that Argentina became a net energy importer and coincided with the finding of the large shale reserves in Neuquén precisely by YPF, now known as Vaca Muerta. YPF at the time was the direct producer of approximately one third of Argentina's total volume. The expropriation took place at the same time as the imposition of the "cepo cambiario", a system of capital controls that made private foreign investment in the sector even less attractive. Not only was the country unable to recover its energy self-sufficiency, but it also entered a period of intense imports that hampered access to dollars and produced a large part of the macroeconomic imbalance of the current economic crisis.

The arrival of Mauricio Macri in 2015 heralded a new phase for the sector with policies more favourable to private initiative. One of the first measures was to establish a fixed price at the "wellhead" of the Vaca Muerta oil fields with the idea of encouraging the start-up of projects. As the economic crisis worsened, the unpopular measure of increasing electricity and fuel prices by more than 30 per cent was chosen, generating enormous discontent in the context of a constant devaluation of the Argentine peso and the rising cost of living. The energy portfolio was marked by enormous instability, with three different ministers who generated enormous legal insecurity by constantly changing the hydrocarbons regulatory framework . Renewable solar and wind energy, boosted by a new energy plan and greater liberalisation of investment, managed to double their energy contribution during Mauricio Macri's time in the Casa Rosada.

Alberto Fernández's first years have been marked by unconditional support for the hydrocarbons sector, with Vaca Muerta being the central axis of his energy policy, announcing the 2020-2023 Gas Plan that will subsidise part of the investment in the sector. On the other hand, despite the context of the health emergency, 39 renewable energy projects were installed in 2020, with an installed capacity of around 1.5 GW, an increase of almost 60% over the previous year. In any case, the continuity of this growth will depend on access to foreign currency in the country, which is essential to be able to buy panels and windmills from abroad. The boom in renewable energy in Argentina led the Danish company Vestas to install the first windmill assembly plant in the country in 2018, which already has several plants producing solar panels to supply domestic demand.

Characteristics of Vaca Muerta

Vaca Muerta is not a field from a technical point of view, it is a sedimentary training of enormous magnitude with dispersed deposits of natural gas and oil that can only be exploited with unconventional techniques: hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. These characteristics make Vaca Muerta a complex activity, which requires attracting as much talent as possible, especially from international players with experience in the exploitation of unconventional hydrocarbons. Likewise, conditions in the province of Neuquén are complex given the scarcity of rainfall and the importance of the fruit and vegetable industry, in direct competition with the water resources required for the exploitation of unconventional oil.

Since finding, the potential of Vaca Muerta has been compared to that of the Eagle Ford basin in the United States, which produces more than one million barrels per day. Evidently, the Neuquén region has neither Texas' oil business ecosystem nor its fiscal facilities, making what might be geologically similar in reality two totally different stories. In December 2020, Vaca Muerte produced 124,000 barrels of oil per day, a figure that is expected to gradually increase over the course of this year to 150,000 barrels per day, about 30% of the 470,000 barrels per day Argentina produced in 2020. Natural gas follows a slower process, pending the development of infrastructure that will allow the transport of large volumes of gas to consumption and export centres. In this regard, Fernández announced in November 2020 the Plan for the Promotion of Argentine Gas Production 2020-2023, with which the Casa Rosada seeks to save dollars by substituting imports. The plan facilitates the acquisition of dollars for investors and improves the maximum selling price of natural gas by almost 50%, to 3.70 dollars per mbtu, in the hope of receiving the necessary investment, estimated at 6.5 billion dollars, to achieve gas self-sufficiency. Argentina already has the capacity to export natural gas to Chile, Uruguay and Brazil through pipelines. Unfortunately, the floating vessel exporting natural gas from Vaca Muerte left Argentina at the end of 2020 after YPF unilaterally broke the ten-year contract with the vessel's owner, Exmar, citing economic difficulties, limiting the capacity to sell natural gas outside the continent.

One of the great advantages of Vaca Muerta is the presence of international companies with experience in the aforementioned US unconventional oil basins. The post-2014 learning curve of the US fracking sector is being applied in Vaca Muerta, which has seen drilling costs fall by 50% since 2014 while gaining in productivity. The influx of US capital may accelerate if Joe Biden's administration fiscally and environmentally restricts oil activities in the country, from agreement with its environmentalist diary . Currently the main operator in Vaca Muerta after YPF is Chevron, followed by Tecpetrol, Wintershell, Shell, Total and Pluspetrol, in an ecosystem with 18 oil companies working in different blocks.

Vaca Muerta as a national strategy

It is clear that achieving energy self-sufficiency will help Argentina's macroeconomic problems, the main headache for its citizens in recent years. No Exempt of environmental risk, Vaca Muerta could be a lifeline for a country whose international credibility is at an all-time low. Alberto Fernández's pro-hydrocarbon narrative follows the line of his Mexican counterpart Andrés guide López Obrador, with whom he intends to lead a new moderate left-wing axis in Latin America. The spectre of the nationalisation of YPF by the now vice-president Cristina Fernández, as well as the recent breach of contract with Exmar, continue to generate uncertainty among international investors. status Moreover, the poor financial performance of YPF, the main player in Vaca Muerta, with a debt of more than 8 billion dollars, is a major drag on the country's oil prospects. Similarly, Vaca Muerta is far from realising its potential, with significant but insufficient production to guarantee revenues that would bring about a radical change in Argentina's economic and social status . In order to guarantee its success, a context of favourable oil prices and the fluid arrival of foreign investors are needed. Two variables that cannot be taken for granted given Argentina's political context and the increasingly strong decarbonisation policy of traditional oil companies.

The big question now is how to reconcile the large-scale fossil fuel development with Argentina's latest commitments on climate change subject : to reduce CO2 emissions by 19% by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Similarly, the promising trajectory of renewable energy development during Mauricio Macri's presidency may lose momentum if the oil and gas sector attracts public and private investment, crowding out solar and wind.

Vaca Muerta is likely to advance slowly but surely as international oil prices stabilise upwards. The possibility of generating foreign currency and boosting a Economics on the verge of collapse should not be underestimated, but expecting Vaca Muerta to solve Argentina's problems on its own can only end in a new episode of frustration in the southern country.

Qatar's economic strengthening and expanding relations with Russia, China and Turkey have made the blockade imposed by its Gulf neighbours less effective.

It is a reality: Qatar has won its battle against the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia after more than three years of diplomatic rupture in which both countries, along with other Arab neighbours, isolated the Qatari peninsula commercially and territorially. Economic and geopolitical reasons explain why the imposed blockade has finally faded without Qatar giving in to its autonomous diplomatic line.

Qatar's Emir Tamim Al Thani at lecture Munich Security 2018 [Kuhlmann/MSC].

article / Sebastián Bruzzone

In June 2017, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Libya, Yemen and the Maldives accused the Al Thani family of supporting Islamic terrorism and the Muslim Brotherhood and initiated a total blockade on trade to and from Qatar until Doha met thirteen conditions. On 5 January 2021, however, Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman welcomed Qatar's Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani with an unexpected embrace in the Saudi city of Al-Ula, sealing the end of yet another dark chapter in the modern history of the Persian Gulf. But how many of the thirteen demands has Qatar met to reconcile with its neighbours? None.

As if nothing had happened. Tamim Al Thani arrived in Saudi Arabia to participate in the 41st Summit of the committee Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) where member states pledged to make efforts to promote solidarity, stability and multilateralism in the face of the challenges in the region, which is confronted by Iran's nuclear and ballistic missile programme, as well as its plans for sabotage and destruction. In addition, the GCC as a whole welcomed the mediating role of Kuwait, then US President Donald J. Trump and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner.

The Gulf Arab leaders' meeting has been a thaw in the political desert after a storm of mutual accusations and instability in what was called the "Qatar diplomatic crisis"; this rapprochement, as an immediate effect, clears the way for the normal preparation of the football World Cup scheduled to take place in Qatar next year. The return of regional and diplomatic understanding is always positive in emergency situations such as an economic crisis, a global pandemic or a common Shia enemy arming missiles on the other side of the sea. In any case, the Al Thani's Qatar may be crowned as the winner of the economic pulse against the Emirati Al Nahyan and the Saudi Al Saud unable to suffocate the tiny peninsula.

The factors

The relevant question brings us back to the initial degree scroll before these lines: how has Qatar managed to withstand the pressure without buckling at all in the face of the thirteen conditions demanded in 2017? Several factors contribute to explaining this.

First, the capital injection by the QIA (Qatar Investment Authority). At the beginning of the blockade, the banking system suffered a capital flight of more than 30 billion dollars and foreign investment fell sharply. The Qatari sovereign wealth fund responded by pumping in $38.5 billion to provide liquidity to banks and revive Economics. The sudden trade blockade by the UAE and Saudi Arabia led to a financial panic that prompted foreign investors, and even Qatari residents, to transfer their assets out of the country and liquidate their positions in fear of a market collapse.

Second, rapprochement with Turkey. In 2018, Qatar came to Turkey's rescue by pledging to invest $15 billion in Turkish assets across subject and, in 2020, to execute a currency swap agreement to raise the value of the Turkish lira. In reciprocity, Turkey increased commodity exports to Qatar by 29 per cent and increased its military presence in the Qatari peninsula against a possible invasion or attack by its neighbours, building a second Turkish military base near Doha. In addition, as an internal reinforcement measure, the Qatari government has invested more than $30 billion in military equipment, artillery, submarines and aircraft from American companies.

Third, rapprochement with Iran. Qatar shares with the Persian country the South Pars North Dome gas field, considered the largest in the world, and positioned itself as a mediator between the Trump administration and the Ayatollah government. Since 2017, Iran has supplied 100,000 tonnes of food daily to Doha in the face of a potential food crisis caused by the blockade of the only land border with Saudi Arabia through which 40 per cent of the food enters.

Fourth, rapprochement with Russia and China. The Qatari sovereign wealth fund acquired a 19% stake in Rosneft, opening the door to partnership between the Russian oil company and Qatar Petroleum and to more joint ventures between the two nations. In the same vein, Qatar Airways increased its stake in China Southern Airlines to 5%.

Fifth, its reinforcement as the world's leading exporter of LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas). It is important to know that Qatar's main economic engine is gas, not oil. That is why, in 2020, the Qatari government launched its expansion plan by approving a $50 billion investment to expand its liquefaction and LNG carrier capacity, and a $29 billion investment to build more offshore offshore platforms at North Dome. The Qatari government has forecast that its LNG production will grow by 40% by 2027, from 77 million tonnes to 110 million tonnes per year.

We should bear in mind that LNG transport is much safer, cleaner, greener and cheaper than oil transport. Moreover, Royal Dutch Shell predicted in its report "Annual LNG Outlook Report 2019" that global LNG demand would double by 2040. If this forecast is confirmed, Qatar would be on the threshold of impressive economic growth in the coming decades. It is therefore in its best interest to keep its public coffers solvent and maintain a stable political climate in the Middle East region at status . As if that were not enough, last November 2020, Tamim Al Thani announced that future state budgets will be configured on the basis of a fictitious price of $40 per barrel, a much smaller value than the WTI Oil Barrel or Brent Oil Barrel, which is around $60-70. In other words, the Qatari government will index its public expense to the volatility of hydrocarbon prices. In other words, Qatar is seeking to anticipate a possible collapse in the price of crude oil by promoting an efficient public expense policy.

And sixth, the maintenance of the Qatar Investment Authority's investment portfolio , valued at $300 billion. The assets of the Qatari sovereign wealth fund constitute a life insurance policy for the country, which can order its liquidation in situations of extreme need.

Qatar has a very important role to play in the future of the Persian Gulf. The Al Thani dynasty has demonstrated its capacity for political and economic management and, above all, its great foresight for the future vis-à-vis the other countries of the Gulf Cooperation committee . The small peninsular "pearl" has struck a blow against Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Abu Dhabi's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, who did not even show up in Al-Ula. This geopolitical move, plus the Biden administration's decision to maintain a hardline policy towards Iran, seems to guarantee the international isolation of the Ayatollah regime from the Persian country.

IDF soldiers during a study tour as part of Sunday culture, at the Ramon Crater Visitor Center [IDF].

ESSAY / Jairo Císcar

The geopolitical reality that exists in the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean is incredibly complex, and within it the Arab-Israeli conflict stands out. If we pay attention to History, we can see that it is by no means a new conflict (outside its form): it can be traced back to more than 3,100 years ago. It is a land that has been permanently disputed; despite being the vast majority of it desert and very hostile to humans, it has been coveted and settled by multiple peoples and civilizations. The disputed territory, which stretches across what today is Israel, Palestine, and parts of Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, and Syria practically coincides with historic Canaan, the Promised Land of the Jewish people. Since those days, the control and prevalence of human groups over the territory was linked to military superiority, as the conflict was always latent. The presence of military, violence and conflict has been a constant aspect of societies established in the area; and, with geography and history, is fundamental to understand the current conflict and the functioning of the Israeli society.

As we have said, a priori it does not have great reasons for a fierce fight for the territory, but the reality is different: the disputed area is one of the key places in the geostrategy of the western and eastern world. This thin strip, between the Tigris and Euphrates (the Fertile Crescent, considered the cradle of the first civilizations) and the mouth of the Nile, although it does not enjoy great water or natural resources, is an area of high strategic value: it acts as a bridge between Africa, Asia and the Mediterranean (with Europe by sea). It is also a sacred place for the three great monotheistic religions of the world, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the "Peoples of the Book", who group under their creeds more than half of the world's inhabitants. Thus, for millennia, the land of Israel has been abuzz with cultural and religious exchanges ... and of course, struggles for its control.

According to the Bible, the main para-historical account of these events, the first Israelites began to arrive in the Canaanite lands around 2000 BC, after God promised Abraham that land ".... To your descendants ..."[1] The massive arrival of Israelites would occur around 1400 BC, where they started a series of campaigns and expelled or assimilated the various Canaanite peoples such as the Philistines (of which the Palestinians claim to be descendants), until the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah finally united around the year 1000 BC under a monarchy that would come to dominate the region until their separation in 924 BC.

It is at this time that we can begin to speak of a people of Israel, who will inhabit this land uninterruptedly, under the rule of other great empires such as the Assyrian, the Babylonian, and the Macedonian, to finally end their existence under the Roman Empire. It is in 63 BC when Pompey conquered Jerusalem and occupied Judea, ending the freedom of the people of Israel. It will be in 70 AD, though, with the emperor Titus, when after a new Hebrew uprising the Second Temple of Jerusalem was razed, and the Diaspora of the Hebrew people began; that is, their emigration to other places across the East and West, living in small communities in which, suffering constant persecutions, they continued with their minds set on a future return to their "Promised Land". The population vacuum left by the Diaspora was then filled again by peoples present in the area, as well as by Arabs.

The current state of Israel

This review of the historical antiquity of the conflict is necessary because this is one with some very special characteristics: practically no other conflict is justified before such extremes by both parties with "sentimental" or dubious "legal" reasons.

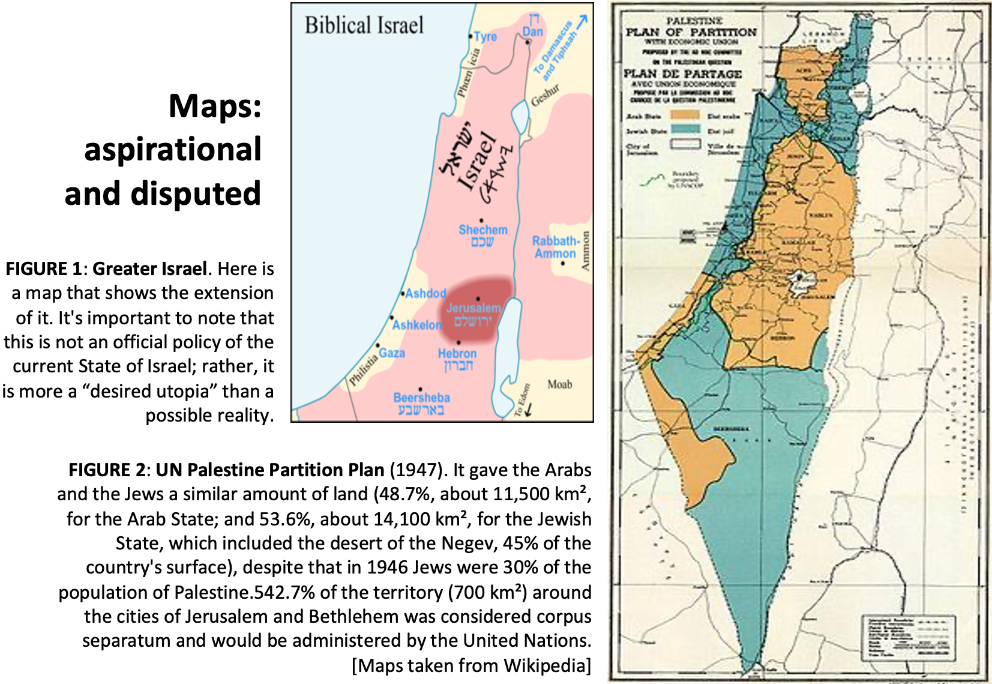

The current state of Israel, founded in 1948 with the partition of the British Protectorate of Palestine, argues its existence in the need for a Jewish state that not only represents and welcomes such a community but also meets its own religious requirements, since in Judaism the Hebrew is spoken as the "chosen people of God", and Israel as its "Promised Land". So, being the state of Israel the direct heir of the ancient Hebrew people, it would become the legitimate occupier of the lands quoted in Genesis 15: 18-21. This is known as the concept of Greater Israel (see map)[2].

On the Palestinian side, they exhibit as their main argument thirteen centuries of Muslim rule (638-1920) over the region of Palestine, from the Orthodox caliphate to the Ottoman Empire. They claim that the Jewish presence in the region is primarily based on the massive immigration of Jews during the late 19th and 20th centuries, following the popularization of Zionism, as well as on the expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians before, during and after the Arab-Israeli war of 1948, a fact known as the Nakba[3], and of many other Palestinians and Muslims in general since the beginning of the conflict. Some also base their historical claim on their origin as descendants of the Philistines.

However, although these arguments are weak, beyond historical conjecture, the reality is, nonetheless, that these aspirations have been the ones that have provoked the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. This properly begins in the early 20th century, with the rise of Zionism in response to the growing anti-Semitism in Europe, and the Arab refusal to see Jews settled in the area of Palestine. During the years of the British Mandate for Palestine (1920-1948) there were the first episodes of great violence between Jews and Palestinians. Small terrorist actions by the Arabs against Kibbutzim, which were contested by Zionist organizations, became the daily norm. This turned into a spiral of violence and assassinations, with brutal episodes such as the Buraq and Hebron revolts, which ended with some 200 Jews killed by Arabs, and some 120 Arabs killed by the British army.[4]

Another dark episode of this time was the complicit relations between the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Almin Al-Husseini, and the Nazi regime, united by a common diary regarding Jews. He had meetings with Adolf Hitler and gave them mutual support, as the extracts of their conversations collect[5]. But it will not be until the adoption of the "United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine" through Resolution 181 (II) of the General Assembly when the war broke out on a large scale. [6] The Jews accepted the plan, but the Arab League announced that, if it became effective, they would not hesitate to invade the territory.

And so, it was. On May 14, 1948, hours after the proclamation of the state of Israel by Ben-Gurion, Israel was invaded by a joint force of Egyptian, Iraqi, Lebanese, Syrian and Jordanian troops. In this way, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War began, beginning a period of war that has not stopped until today, almost 72 years later. Despite the multiple peace agreements reached (with Egypt and Jordan), the dozens of United Nations resolutions, and the Oslo Accords, which established the roadmap for achieving a lasting peace between Israel and Palestine, conflicts continue, and they have seriously affected the development of the societies and peoples of the region.

The Israel Defense Forces