Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

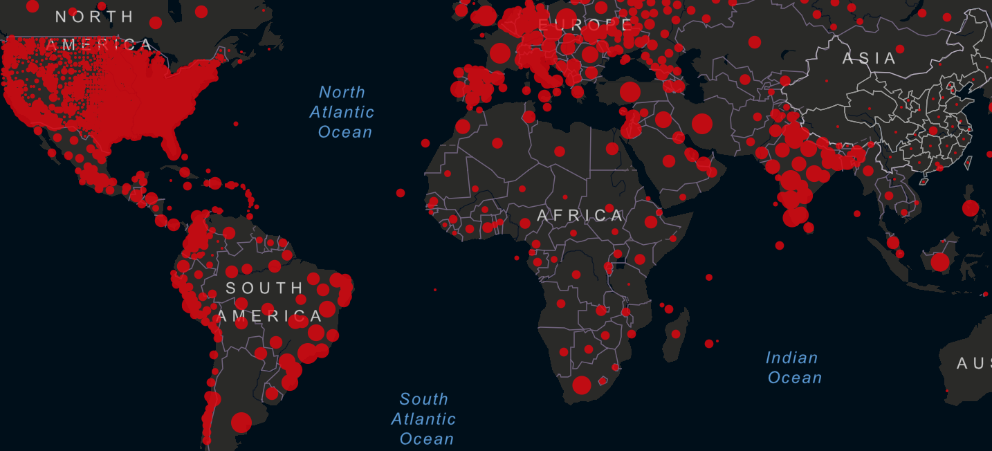

Image of the world map produced by the John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

REPORT SRA 2021

May 2021

PRESENTATION

Covid-19, an unexpected factor

MAY 2021-The pandemic caused by the Covid-19 virus has had a major impact throughout the world, and especially in the Americas: three of the four countries with the most deaths - the United States, Brazil and Mexico, with a total of more than one million deaths - are in the Western Hemisphere. Latin America has been the area most affected by the disease, in proportion to its population, and with the worst economic consequences. This status has meant, in terms of security, a special regional vulnerability to external powers and internal mafias.

If two years ago we launched this report of American Regional Security (ARS) stating that geopolitics had returned to the continent, due to the growing interest of China and Russia in the area of traditional US influence, it can now be said that these two extra-hemispheric powers have taken advantage of the health emergency to deploy a "diplomacy of vaccines" and consolidate their influence, while the US prepares its own flow of neighbouring financial aid , on the verge of concluding the inoculation of its population.

In this context, significant episodes occurred during 2020. China's food security demands have reinforced the presence of Chinese fishing fleets in the vicinity of the waters of several South American countries, whose fishing grounds are threatened by illegal fishing practices and alleged encroachment on their exclusive economic zones. This has led to some collective security movement and increased engagement with the US Southern Command.

On the other hand, organised crime has also taken advantage of the pandemic status , relying on the distraction of the authorities in another subject of efforts. In the last year, Paraguay has emerged as a major hub for cocaine outflows from the interior of the continent, while at the same time consolidating its position as South America's main producer of marijuana, at a time when this crop is emerging as a legal business opportunity in new countries. For their part, Guatemala and Honduras are consolidating their 'trials' in coca cultivation, making a leap - scarcely quantitative, but certainly qualitative - in the world of drug trafficking. The positive news is that the peace process and the confinements of the pandemic have reduced homicides in Colombia to historic lows.

CONTENTS

SUMMARY EXECUTIVE

Covid makes Latin America more vulnerable to external powers and internal mafias

MARITIME SAFETY

China's uncontrolled fishing alerts governments with major fishing grounds under threat

Paola Rosenberg

EXTRAHEMISPHERIC PRESENCE

Vaccine diplomacy: more 'Western' doses, but China and Russia consolidate penetration

Emili J. Blasco

EXTRAHEMISPHERIC PRESENCE

Iran takes gold from a Venezuela that no longer has oil to pay for the favours.

Maria Victoria Andarcia

REACTION OF THE UNITED STATES

The US Southern Command is warning more about China's advance in the region.

Diego Diamanti

MARAS

US begins to prosecute MS-13 members as terrorists

Xabier Ramos Garzón

PUBLIC SAFETY

Peace process and Covid reduce homicides in Colombia to historic lows

Isabella Izquierdo

NARCOTRAPHIC

Coca cultivation 'trials' increase in Honduras and Guatemala, once only transit countries

Eduardo Villa Corta

NARCOTRAPHIC

Paraguay remains South America's largest marijuana producer

Eduardo Uranga

![Gacaca trials, a powerful instrument of transitional justice implemented in Rwanda [UNDP/Elisa Finocchiaro].](/documents/16800098/0/Foto_Africa-Peacebuilding_larga.png/14888a0b-3a0c-2ee5-71dc-e75c22249faf?t=1621873383792&imagePreview=1)

ESSAY / María Rodríguez Reyero

One of the main questions that arise after a conflict comes to an end is what the reconstruction process should be focused on. Is it more important to forget the past and heal the wounds of a community or to ensure that the perpetrators of violence are fairly punished? Is the concept of peacebuilding in post-conflict societies compatible with justice and the punishment for crimes? Which one should prevail? And most importantly, which one ensures a better and more sustainable future for the already harshly punished inhabitants?

One of the main reasons in defence of the promotion of justice and accountability in post-conflict communities is its significance when it comes to retributive reasons: those who committed such atrocious crimes deserve to get the consequences. The accountability also discourages future degradations, and some mechanisms such as truth commissions and reparations to the victims allow them to have a voice, as potentially cathartic or healing. They may also argue that accountability processes are essential for longer-term peacemaking and peacebuilding. Another reason for pursuing justice and accountability is how the impunity of past crimes could affect the legitimacy of new governments, as impunity for certain key perpetrators will undermine people's belief in reconstruction and the possibilities for building a culture of respect for rule of law.[1]

On the other hand, peacebuilding, which attempts to address the underlying causes of a conflict and to help people to resolve their disputes rather than aiming for accountability, remains a quite controversial term, as it varies depending on its historical and geographical context. In general terms, peacebuilding encompasses activities designed to solidify peace and avoid a relapse into conflict[2]. According to Brahimi, those are undertaken to reassemble the foundations of peace and provide tools for building up those foundations, more than just focusing on the absence of war[3]. Some of the employed tools to achieve said aims typically include rule of law promotion and with the tools designed to promote security and stability: disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of ex-combatants (DDR), and security sector reform (SSR) and others such as taking custody of and destroying weapons, repatriating refugees, offering advisory and training support for security personnel, monitoring elections, advancing efforts to protect human rights, reforming or strengthening government institutions and promotion of the formal and informal process of political participation.[4]

Those conflict resolution and peacebuilding activities can be disrupted by accountability processes. [5] The concern is that accountability initiatives might even block possible peace agreements and lengthen the dispute as they remove the foundations of the conflict, making flourish bad feelings and resentment amongst the society. The main reason behind this fear is that those likely to be targeted by accountability mechanisms may therefore resist peace deals. This explains why on many occasions and aiming for peace, amnesties have been given to secure peace agreements Likewise, there is a prevailing concern that transitional justice tools may reduce the impact in the short term the durability of a peace settlement as well as the effectiveness of further peace-building actions.

Despite the arguments in favour and against both mechanisms, the reality is that in practice post-conflict societies tend to strike a balance between peacebuilding and transitional justice. Both are multifaceted processes that do not rely on one system to accomplish their ends, that frequently converge. However, their activities on occasions collide and are not complimentary. This essay examines one of the dilemmas in building a just and durable peace: the challenging and complex relationship between transitional justice and peacebuilding in countries emerging from conflict.

To do so, this essay takes into consideration Rwanda, a clear example of the triumph of transitional justice, after a tragic genocide in 1994. From April to July 1994, between 800,000 and one million ethnic Tutsis were brutally killed during a 100-day killing spree perpetrated by Hutus[6]. After the genocide, Rwanda was on the edge of total collapse. Entire villages were destroyed, and social cohesion was in utter deterioration. In 2002, Rwanda boarded on the most arduous practice in transitional justice ever endeavoured: mass justice for mass atrocity, to judge and restart a stable society after the bloody genocide. To do so, Rwanda decided to put most of the nation on trial, instead of choosing, as other post-conflict states did (such as Mozambique, Uganda, East Timor, or Sierra Leone), amnesties, truth commissions, selective criminal prosecutions.[7]

On the other hand, Sierra Leone is a clear example of the success of peacebuilding activities, after a civil war that led to the deaths of over 50,000 people and a poverty-stricken country. The conflict faced the Revolutionary United Front (RUF[8]) against the official government, due to a context of bad governance and extensive injustice. It came to an end with the Abuja Protocols in 2001 and elections in 2002. The armed factions endeavoured to avoid any consequences by requesting an amnesty as well as reintegration assistance to ease possible societal ostracism. It was agreed only because the people of Sierra Leone so severely needed the violence to end. However, the UN representative to the peace negotiations stated that the amnesty did not apply to international crimes, President Kabbah asked for the UN's assistance[9] and it resulted in the birth of Sierra Leone's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL or Special Court).[10]

Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) and transitional justice

Promoting short- and longer-term security and stability in conflict-prone and post-conflict countries in many cases requires the reduction and structural transformation of groups with the capacity to engage in the use of force, including armies, militias, and rebel groups. In such situations, two processes are of remarkable benefit in lessening the risk of violence: DDR (disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration) of ex-combatants; and SSR (security sector reform).

DDR entails a range of policies and programs, supporting the return of ex-combatants to civilian life, either in their former communities or in different ones. Even if not all ex-combatants are turned to civilian life, DDR programs may lead to the transfer and training, of former members of armed groups to new military and security forces. The essence of DDR programming and the guarantees it seeks to provide is of utmost importance to ensuring peacebuilding and the possibility of efficient and legitimate governance.

It is undeniable that soldiers are unquestionably opposing to responsibility processes enshrined in peace agreements: they are less likely to cede arms if they dread arrest, whether it is by an international or domestic court. This intensifies their general security fears after the disarming process. In many instances, ex-combatants are integrated into state security forces, which makes the promotion of the rule of law, difficult, as the groups charged with enforcing new laws may have the most to lose through the implicated reforms. It is also likely to lessen citizen reliance on the security forces. The incorporation of former fighters not only in the new military but also in new civilian security structures is common: for example, in Rwanda, the victorious RPF dominated the post-genocide security forces.

While the spectre of prosecutions most obviously may impede DDR processes, there is a lesser possibility that it might provide incentives for DDR, as might happens where amnesty or reduced sentences are offered as inducements for combatants to take part in DDR processes. For them to be effective, the reliability of both the threat of prosecution and the durability of amnesty or other forms of protection are essentials whether it is in national or international courts. Even if this is not related to the promotion of transitional justice processes, it is another example of how it can have a long-term effect on the respect of human rights and the prevention of future breaches.

As previously stated, some DDR and transitional justice processes may share alike ends and even employ similar mechanisms. A variety of traditional processes of accountability and conflict resolution often also seek to promote reconciliation. DDR programs increasingly include measures that try to encourage return, reintegration, and if possible, reconciliation within communities. This willingness of victims to forgive and forget could in theory be promoted through a range of reconciliation processes like the ones promoted by transitional justice with the assistance of tools like truth commissions, which facilitate a dialogue that allows inhabitants to move forward while accepting the arrival of former perpetrators.

The triumph of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) in 1994 finally put an end to the genocide in the country. The new government focused on criminal accountability for the 1994 genocide and as a result of this prioritization, the needs of survivors have not been met completely Rwanda is the paradigm and perfect example of prosecution of perpetrators of mass atrocity by the employment of transitional justice mechanisms, that were kept separated from DDR programs in order not to interfere with the attribution of responsibilities. [11] The Rwandan one is a case where DDR largely worked notwithstanding firmly opposing amnesty. Proof of this outstanding DDR success is how Rwanda has managed to successfully reintegrate around 54,000 combatants since 1995 thanks to the work of the Rwandan Demobilization and Reintegration Commission (RDRC). Another clear evidence of the effectiveness of DDR methods in Rwanda is the reintegration of child soldiers. Released child soldiers were installed in a special school (Kadogo School), which started with 2,922 children. By 1998 when it closed, the RDRC reported that 73% of its students had reunited with one or both parents successfully.[12]

On the other hand, Sierra Leone's case on DDR was quite different from Rwanda's success, as Sierra Leone's conflict involved the prevalence of children associated with armed forces and groups (CAAFG). By the time the civil war concluded in 2002, data from UNICEF estimates that roughly 6,845 children have been demobilized,[13] although the actual number could be way higher. Consequently, the DDR program in Sierra Leone is essentially focused on the reintegration of young soldiers, an initiative led by UNICEF with the backing of some local organisations, such as the National Committee on DDR (NCDDR)of Sierra Leone. Nonetheless, in practice, Sierra Leone's military did not endure these local guidelines, and as a result the participation of children in the process often had to be arranged by UNICEF peacekeepers in most cases. In addition to that initial local reluctance, some major quandaries aroused when it came to the reintegration of children in the new peace era in Sierra Leone, mainly due to the tests and requirements for children to have access to DDR programs, such as to present a weapon and demonstrate familiarity with it. [14] As a result, many CAAFG were excluded from the DDR process, primarily girls who were predominantly charged with non-directly military activities such as "to carry loads, do domestic work, and other support tasks."[15]In addition, many CAAFG were excluded from the DDR process.

Thus, the participation of girls in Sierra Leone's DDR was particularly low and many never even received support. While it is not clear how many girls were abducted during the war, data from UNICEF calculates that out of the 6,845 overall children demobilized, 92% were boys and only 8% were girls. The Women's Commission for Refugee Women and Children has pointed out that as many as 80 per cent of rebel soldiers were between the ages of 7 and 14, and escapes from the rebel camps reported that the majority of camp members were young captive girls. [16] Research also reported that 46% of the girls who were excluded from the program confirmed that not having a weapon was the reason for exclusion. In other cases, girls were not permitted by their husbands to go through the DDR,2 whilst others chose to opt-out themselves due to worry of stigmatization back in their neighbourhoods. [17] It is worth noting that many of those who succeeded to go through the demobilization phase "reported sexual harassment at the ICCs, either by male residents or visiting adult combatants", while others experienced verbal abuse, beatings, and exclusion in their communities.[18]

Another problem that underlines the importance of local leadership in DDR processes is that the UN-driven DDR program lets children decide to receive skill training rather than attending school if they were above 15 years. However, the program provided little assistance with finding jobs upon completion of the apprenticeship. Besides, little market examination was done to learn the demands of the local economy where children were trying to reintegrate into, so they are far more than the Sierra Leonean economy could absorb, which resulted in a lack of long-term employment for demobilized child soldiers. Studies by the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers[19] and Human Rights Watch[20] revealed that adolescents who had previouslyhand been part of armed organisations during the war in Sierra Leone were re-recruited in Liberia or Congo because of the frustration and the lack of economic options for them back in Sierra Leone.

Promotion of the rule of law and its contributions to peacebuilding

Amongst many others, the promotion of the rule of law in post-conflict countries is a fundamental factor in peacebuilding procedures. It contributes to eradicating many of the causes of emerging conflicts, such as corruption, disruption of law... Even if it may seem contradictory, peacebuilding activities in support of the rule of law may become contradictory to transitional justice. Sometimes processes of transitional justice may displace resources, both capital, and human, that might otherwise be given to strengthening the rule of law. For instance, in Rwanda, it has been claimed that the resources invested in the development and assistance to national courts should have been equal to those committed to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), and the extent to which trials at the ICTR have had an impact domestically remains to be seen.

However, transitional justice also presents other challenges to the reconstruction of the rule of law. Transitional justice processes might also destabilize critically imperfect justice sectors, making it more difficult to improve longer-term rule of law. They can stimulate responses from perpetrators which could destabilize the flimsy harmony of nascent governments, as they might question its legitimacy or actively attempt to undermine the authority of public institutions. Judging former perpetrators is an arduous task that is also faced with corruption and lack of staff and resources on many occasions. Additionally, the effort by national courts to prosecute criminals is an undue burden on the judicial system, which is severely damaged after a conflict and in many cases not ready to confront such atrocious crimes and the long processes they entail. Processes to try those accused of genocide in Rwanda, where the national judicial system was devastated after the genocide, have put great pressure on the judicial system, and the lack of capacity has resulted that many arrested remained in custody for years without having been convicted or even having had their cases heard, in the majority of the cases in appalling prison conditions. Such supposed accountability initiatives may have a counterproductive effect, contributing to a sense of impunity and distrust in justice processes.

Despite the outlined tensions, transitional justice and rule of law promotion are also capable to work towards the same ends. A key goal of transitional justice is to contribute to the rebuilding of a society based on the rule of law and respect for human rights, essential for durable peace. The improvement of a judiciary based on transparency and equality is strictly linked to the ability of a nation to approach prior human rights infringements after a conflict. [21] Both are potentially mutually reinforcing in practice if complementarities can be exploited. Consequently, rule of law advancement and transitional justice mechanisms however combine in some techniques.

To start with, the birth of processes to address past transgressions perpetrated during the conflict, both international and domestic processes, can help to restore confidence in the justice sector, especially when it comes to new arising democratic institutions. The use of domestic courts for accountability processes helps to place the judiciary at the centre of the promotion and protection of human rights of the local population, which contributes to the intensification of trust not only in the judicial system but also in public institutions and the government in general. Government initiation of an accountability process may indicate an engagement to justice and the rule of law beforehand. Domestically-rooted judicial processes, as well as other transitional justice tools, such as commissions of inquiry, may also support the development of mechanisms and rules for democratic and fair institutions by establishing regularized procedures and rules and promoting discussions rather than violence as a means of resolving differences and a reassuring population that their demands will be met in independent, fair and unbiased fora, be this a regular court or an ad hoc judicial or non-judicial mechanism. This is not to assume that internationally driven transitional justice mechanisms do not have a role to play in the development of the rule of law in the countries for which they have been established, as the hybrid tribunal of Sierra Leone demonstrates.[22]

In general terms, the refusal of impunity for perpetrators and the reformation of public institutions are considered the basic tools for the success of transitional justice. Transcending the strengthening of the judiciary, different reform processes can strengthen rule of law and accountability: institutions that counteract the influence of certain groups (including the government) like human rights commissions or anti-corruption commissions, may contribute to the establishment of a strong institutional and social structure more capable of confronting social tensions and hence evade the recurrence to conflict.[23]

Achieving an effective transitional justice strategy in Rwanda is an incredible challenge taking into consideration the massive scale as well as the harshness of the genocide, but also because of the economic and geographical limitations that make perpetrators and survivors live together in the aftermath. To facilitate things, other post-conflict states with similarly devastatingly high numbers of perpetrators have opted for amnesties or selective prosecutions, but the Rwandan government is engaged in holding those guilty for genocide responsible, thus strongly advocating for the employment of transitional justice. This is being accomplished through truth commissions, Gacaca traditional courts, national courts, and the international criminal tribunal for Rwanda combined. This underlines the dilemma of whether national or international courts are more efficient in implementing transitional justice.

Gacaca focuses on groups rather than individuals, seeks compromise and community harmony, and emphasizes restitution over forms of punishment. Moreover, it is characterized by accessibility, economy, and public participation. It encourages transparency of proceedings with the participation of the public as witnesses, who gain the truth about the circumstances surrounding the atrocities suffered during the genocide. Also, it provides an economic benefit, as Gacaca courts can try cases at a greater speed than international courts, thus reducing considerably the monetary cost as the number of incarcerated persons waiting for a trial is significantly reduced.

Alongside the strengths of the Gacaca system come flaws that seem to be inherent in the system. Many have come to see the Gacaca as an opportunity to require revenge on enemies or to frighten others with the threat of accusation, instead of injecting a sense of truth and reconciliation: the Gacaca trials have aroused concern and intimidation amongst many sectors of the population. Additionally, the community service prescribed to convicted perpetrators frequently is not done within the community where the crime was committed but rather done in the form of public service projects, which enforces the impression that officials may be using the system to benefit the government instead of helping the ones harmed by the genocide. Another proof of the control of Gacaca trials for benefit of the government is manifested by the prosecutions against critics of the post-genocide regime.

On the other hand, Sierra Leone's situation is very different from the one in Rwanda. To help restore the rule of law, the Special court settled in Sierra Leone must be seen as a role model for the administration of justice, and to promote deterrence it must be deemed credible, which is one of its main problems. [24] There is little confidence in the international tribunals amongst the local population, as the Court's nature makes it non-subordinated to the Sierra Leonean court system, and thus being an international tribunal independent from national control. [25] Nevertheless, it is considered as a "hybrid" tribunal since its jurisdiction extends over both domestic and international crimes and it relies on national authorities to enforce its orders. Still, in practice, there is no genuine cooperation between the government and the international community, as there is a limited extent of government participation in the Special Court's process and the lack of consultation with the Sierra Leonean population before the Court's endowment. This absence of national participation, despite causing scepticism over citizens, has the benefit that it remains more impartial when it comes to the proceedings against CDF leaders.

Another major particularity of the case of Sierra Leone and its process of implementation of transitional justice is once again the high degree of implication of children in the conflict, not only as victims but also as perpetrators of crimes. The responsibility of child soldiers for acts committed during armed conflict is a quite controversial issue. In general, under international law, the prosecution of children is not forbidden. However, there is no agreement on the minimum age at which children can be held criminally responsible for their acts. The Rome Statute, instituting the International Criminal Court (ICC), only provides the Court jurisdiction over people over eighteen years. Although not necessarily directly addressed to the prosecution of child soldiers, Article 40 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child foresees the trials of children (under eighteen), ordering that the process should consider their particular needs and vulnerabilities due to their shortage.

The TRC for Sierra Leone was the first one to focus on children's accountability, directly asserting jurisdiction over any person who committed a crime between the ages of fifteen and eighteen. Concerning child soldiers, the commission treated all children equally, as victims of war, but also studied the double role of children as both victims and perpetrators. It emphasized that it was not endeavouring to guilt but to comprehend how children came to carry out crimes, what motivated them, and how such offences might be prevented. Acknowledging that child soldiers are essentially victims of serious abuses of human rights and prioritizing the prosecution of those who illegally recruited them is of utmost importance. Meticulous attention was needed to guarantee that children's engagement did not put them at risk or expose them to further harm. Proper safeguard and child-friendly procedures were ensured, such as special hearings, closed sessions, a safe and comfortable environment for interviews, preserving the identity of child witnesses, and psychological care, amongst others.

However, shall children that have committed war crimes be prosecuted in the first place? If not, is there a risk that tyrants may assign further slaughter to be performed by child soldiers due to the absence of responsibility they might possess? The lack of prosecution could immortalize impunity and pose a risk of alike violations reoccurring eventually, as attested by the re-recruitment of some child soldiers from Sierra Leone in other armed conflicts in the area, such as in Liberia. Considering the special conditions of child soldiers, it becomes clear that the RUF adult leaders primarily are the ones with the highest responsibility, and hence must be prosecuted.[26]

It is known that both the Sierra Leonean government and the RUF were involved in the recruitment of child soldiers as young as ten years old, which is considered a violation of both domestic and international humanitarian law. Under domestic law, in Sierra Leone, the minimum age for voluntary recruitment is eighteen years. International humanitarian law, (Additional Protocol II) fifteen is established as the minimum age qualification for recruitment (both voluntary or compulsory) or participation in hostilities (includes direct participation in combat and active participation linked to combat such as spying, acting as couriers, and sabotage). Additionally, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child[27] to which Sierra Leone is a signatory, requires "state parties . . . to take all necessary measures to ensure that no child below age eighteen shall take direct part in hostilities" and "to refrain in particular from recruiting any child."

Nevertheless, victims who have been hurt by children also have the right to justice and reparations, and it also comes to ask whether exempting children of accountability for their crimes is in their best interest. When the child was in control of their actions (not coerced, drugged, or forced) acknowledgement might be an important part of staff healing that also adds to their acceptance back in their communities. The prosecution, however, should not be the first stage to hold child soldiers accountable, as TRC in Sierra Leone also performs alternatives, so the possibility of using those should first be inquired, as these alternatives put safeguards to ensure the best interest of the child and the main aim is restorative justice and not criminal prosecution.

Conclusions

Finally, after parsing where peacebuilding and justice clash and when do they have shared methods, we can assert that establishing an equitable and durable peace requires pursuing both peacebuilding and transitional justice activities, taking into consideration how they interact and the concrete needs of each community, especially when it comes to the needs of former child soldiers and the controversial discussion around the need for their accountability and reinsertion in communities, as despite the pioneer case of Sierra Leone, the unusual condition of a child combatant, which is both victim and perpetrator still presents dilemmas concerning their accountability in international criminal law.[28]

Additionally, it becomes of utmost importance in assessing post-conflict societies, whether it is to implement peacebuilding measures such as DDR or to apply justice and search for accountability, that international led initiatives include in their program's local organisations. Critics of international criminal justice often assume that criminal accountability for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes are better handled at the national level. While this may well hold for liberal democracies, it is far more problematic for post-conflict successor regimes, where the benefits of the proximity to the affected population must be seriously weighed against the challenges facing courts placed in conflict-ridden societies with weak and corrupt judiciaries.

Local systems however have more legitimacy and capacity than devastated formal systems, and they promise local ownership, access, and efficiency, which seems to be the most appropriate way to ensure peace and endurability of peace. Additionally, restorative justice methods put into place thanks to local initiatives emphasize face-to-face intervention, where offenders have the chance to ask for forgiveness from the victims. In many cases restitution replaces incarceration, which facilitates the reintegration of offenders into society as well as the satisfaction of the victims.

To conclude, it has become clear that improving the interaction between peacebuilding and transitional justice processes requires coordination as well as a deep knowledge and understanding of said community. It is therefore not a question of deciding whether peacebuilding initiatives or transitional justice must be implemented, but rather to coordinate their efforts to achieve a sense of sustainable and most-needed peace in post-conflict countries. Taken together, and despite their contradictions, these processes are more likely to succeed in their seek to foster fair and enduring peace.

[1] Sooka, Y., 2006. Dealing with the past and transitional justice: building peace through accountability. [online] International Review of the network Cross. https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/a21925.pdf [Accessed 5 April 2021].

2 Boutros-Ghali, B. (1992). An diary for Peace:Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking and peace-keeping.Report of the Secretary-General UN: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/145749 [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[Brahimi (n.d.). Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations. 55th Session: Brahimi Report | United Nations Peacekeeping [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[4] United Nations Secretary General (1992). "An Agenda for Peace, Preventive diplomacy, peacemaking and peace-keeping UN Doc. A/47/277 - S/24111, 17 June.", title VI, paragraph 55.<A_47_277.pdf (un.org)>. [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[5] Sooka, Y., 2006. Dealing with the past and transitional justice: building peace through accountability. [online] International Review of the Red Cross. Available at: < https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/a21925.pdf > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[6] Roser, M. and Nagdy, M., 2021. Genocides. [online] Our World in Data. Available at: < Genocides - Our World in Data > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[7] Waldorf, L., 2006. Mass Justice For Mass Atrocity: Rethinking Local Justice As Transitional Justice. [online] Temple Law Review. Available at: < https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/temple79&div=7 > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[8] Gibril Sesay, M. and Suma, M., 2009. Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Sierra Leone. [online] International Center for Transitional Justice. Available at: < https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-DDR-Sierra-Leone-CaseStudy-2009-English.pdf > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[9] Roht-Arriaza, N., & Mariezcurrena, J. (Eds.). (2006). Transitional Justice in the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Truth versus Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chapter 2, Sigal HOROVITZ: Transitional criminal justice in Sierra Leone. <(PDF) Transitional Criminal Justice in Sierra Leone | Sigall Horovitz - Academia.edu >[Accessed 5 March 2021]

[10] Connolly, L., 2012. Justice and peacebuilding in postconflict situations: An argument for including gender analysis in a new post-conflict model. [online] ACCORD. Available at: < https://www.accord.org.za/publication/justice-peacebuilding-post-conflict-situations/ > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[11] Waldorf, L., 2009. Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Rwanda. [online] Intenational Center for Transitional Justice. Available at: < https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-DDR-Rwanda-CaseStudy-2009-English.pdf >[Accessed 5 April 2021].

[13] UNICEF (2004). From Confict to Hope:Children in Sierra Leone's Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration Programme. [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[14] SESAY, M.G & SUMA, M. (2009), "Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Sierra Leone", International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[15] WILLIAMSON, J. (2006), “The disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of child soldiers: social and psychological transformation in Sierra Leone”, Intervention 2006, Vol. 4, No. 3, Available from: < http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.600.1127&rep=rep1&type=pdf> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[16]: A. B. Zack-Williams (2001) Child soldiers in the civil war in Sierra Leone, Review of African Political Economy, 28:87, 73-82, DOI: 10.1080/03056240108704504 [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[17] MCKAY, S. & MAZURANA, D. (2004), "Where are the girls? Girls in Fighting Forces in Northern Uganda, Sierra Leone and Mozambique: Their Lives During and After War",Rights & Democracy. International Centre for Human Rights & Democratic Development, [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[18] UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) (2005), “The Impact of Conflict on Women and Girls in West and Central Africa and the Unicef Response”, Emergencies, pg.19,Available from: < https://www.unicef.org/emerg/files/Impact_conflict_women.pdf> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[19] Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers (2006), "Child Soldiers and Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation and Reintegration in West Africa". [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[20] HRW (Human Rights Watch) (2005), “Problems in the Disarmament Programs in Sierra Leone and Liberia [1998-2005]”, Reports Section, Available from: <https://www.hrw.org/reports/2005/westafrica0405/7.htm> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[21] Herman, J., Martin-Ortega, O. and Sriram, C., 2012. Beyond justice versus peace: transitional justice and peacebuilding strategies. 1st ed. Routledge. <Beyond justice versus peace: transitional justice and peacebuilding strategies | Taylor & Francis Group> [Accessed 5 March 2021]

[22] Young, G., n.d. Transitional Justice in Sierra Leone: A Critical Analysis. [online] PEACE AND PROGRESS – THE UNITED NATIONS UNIVERSITY GRADUATE STUDENT JOURNAL. Available at: < https://postgraduate.ias.unu.edu/upp/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/upp_issue1-YOUNG.pdf > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[23] Herman, J., Martin-Ortega, O. and Sriram, C., 2012. Beyond justice versus peace: transitional justice and peacebuilding strategies. 1st ed. Routledge. <Beyond justice versus peace: transitional justice and peacebuilding strategies | Taylor & Francis Group> [Accessed 5 March 2021]

[24] Stensrud, E., 2009. New Dilemmas in Transitional Justice: Lessons from the Mixed Courts in Sierra Leone and Cambodia. [online] Journal of peace research. Available at: <New Dilemmas in Transitional Justice: Lessons from the Mixed Courts in Sierra Leone and Cambodia on JSTOR> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[25] Roht-Arriaza, N., & Mariezcurrena, J. (Eds.). (2006). Transitional Justice in the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Truth versus Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chapter 2, Sigal HOROVITZ: Transitional criminal justice in Sierra Leone. <(PDF) Transitional Criminal Justice in Sierra Leone | Sigall Horovitz - Academia.edu >[Accessed 5 March 2021]

[26] Zarifis, Ismene. "Sierra Leone's Search for Justice and Accountability of Child Soldiers." Human Rights Brief 9, no. 3 (2002): 18-21. [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[27] Article 22 of the AFRICAN CHARTER ON THE RIGHTS AND WELFARE OF THE CHILD , achpr_instr_charterchild_eng.pdf (un.org). [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[28] Veiga, T. G. (2019). A New Conceptualisation of Child Reintegration in Conflict Contexts. E International Relations: https://www.e-ir.info/2019/06/21/a-new-conceptualisation-of-child-reintegration-in-conflict-contexts/.[Accessed 5 April 2021].

[Carlos Lopes, Africa in Transformation: Economic Development in the Age of Doubt (London: Palgrave, 2018), 175 pp.]

REVIEW / Emilija Žebrauskaitė

The emergence of a new discourse about 'Africa rising' is not at all surprising. After all, the continent is home to many fastest-growing economies of the world and the African sub-regions experienced economic growth way above the world average for more than a decade. New opportunities are opening up in the continent and Africa is becoming to be viewed as an attractive opportunity for investments and entrepreneurship.

However, Carlos Lopes views the discourse about 'Africa rising' as a narrative that was created by foreigners interested in the continent and the economic opportunities it offers, without the consideration to the Africans themselves. In his book Africa in Transformation: Economic Development in the Age of Doubt Lopes presents an alternative view of the continent, it's challenges and achievements: an alternative view that is centered on Africans and their needs as opposed to the interests of the foreign investors.

The book describes a wide scope of topics from political to economic to intellectual transformation, all of them focusing on the rethinking of the traditional development models and providing a new, innovative approach to building the continent and its future.

One of the main points Lopes highlights is the importance of the agricultural transformation in Africa as a starting point for industrialization and development. The agricultural sector provides nearly 65% of Africa's population with employment. It is, therefore, one of the most important sectors for the continent. Drawing on historical evidence of other countries successfully climbing out of poverty relying on the transformation of the local agriculture, he comments that while some African countries have managed to increase their agricultural production, comparing to the rest of the world, the progress so far is pretty modest.

Lopes also points out that countries with low agricultural production are less industrialised as well. The solution he offers for Africa's industrialisation starts with agricultural transformation. He argues that the first step is the need for agricultural transformation that would lead to increased labour productivity, which would, in turn, lead to greater access to food per unit of labour, reducing the price of food relative to the income of the worker of the agricultural sector, allowing for the budget surplus to appear and become an impetus for the demand of goods and services beyond the agricultural sector.

While Lopes argues that the increase of Africa's labour productivity is as best "modest" compared to other developing regions of the world, at first glance this statement might seem contradictory to the fact that many African countries are among the fastest-growing economies of the world. However, the critique of Lopes highlights that despite the economic growth of the continent, it did not generate sufficient jobs, nor it was equally distributed across the continent. Furthermore, the growth did not protect African economies from the rocky nature of the commodity exports on which the continent relies, making the growth unstable.

According to Lopes, not only the diversification of the production structures is required, there is a need for the creation of ten million new jobs in order to absorb the immense youth number entering the markets. As the trade liberalisation forced unequal competition upon local African industries, Lopes suggests using smart protectionist measures that are not directly trade-related and therefore outside of the influence of WTO. In the end, the African economy must be internally driven and less dependent, and the policies should focus to protect it.

This leads us to another focus of the book, namely the lack of policy space for African countries. The economic and political theories reflected upon Africa by the developed countries, specifically the US, do not leave enough space for African countries to develop their own policies based on local circumstances and necessities. In cases where the ideas imposed from abroad fail to function in African circumstances, the continent is left without much space for adjustment. Lopes discusses the failure of the Bretton Woods institutions to remain impartial in their policymaking, and the disastrous effect the neo-liberal policies, enforced on the whole world until the crisis of 2008.

While Lopes agrees that the lack of the capability of enforcing the IMF and World Bank policies by the implementing countries contributed to their ineffectiveness, the lack of flexibility from the part of the international organisations to adapt the policies to the regional circumstances and the arrogant denial to admit their inefficiency were the major factors contributing to the negative social impact, namely inequality, that neo-liberalism enhanced in Africa. According to Lopes, now that the trustworthiness of the international financial institutions has decreased, more space is left for Africa to reformulate and enforce its own policies, adapting them to the existing circumstances and needs.

In the end, the book approaches the problems faced by modern-day Africa from a multidisciplinary point of view, discussing topics ranging from ideology and ecology to economy and politics. Carlos Lopes is a loud and confident voice when it comes to the contribution of the 'Africa rising' narrative. While he does not deny the accomplishment of the continent, he is cautious about the narrative that portrays Africa as an economic unit, interesting due to and only because of new economic possibilities that are opening for foreign interests. His alternative is the idea of 'Africa in transformation' - the view that focuses on the growth of the possibilities for the people of Africa and transformation of a continent from an object of someone's exploitation, to a place with its own opportunities and opinions, offering the world new ideas on the most important topic of contemporary international debates.

First high-level US-China meeting of the Biden era, to be held in Alaska on 18 March 2021 [State Department].

essay / Ramón Barba

President Joe Biden is cautiously building his Indo-Pacific policy, seeking to build an alliance with India on which to build an order to counter the rise of China. Following his entrance in the White House, Biden has kept the focus on this region, albeit with a different approach than the Trump Administration. While it is true that the main goal is still about containing China and defending free trade, Washington is opting for a multilateral approach that gives greater prominence to QUAD[1] and takes special care over relations with India. As a standard-bearer for the free world and democracy, the Biden Administration seeks to renew US leadership in the world and particularly in this critical region. However, although the relationship with India is at a good moment, especially given the signature of agreement scholarship[2] reached at the end of the Trump Administration, the interaction between the two countries is far from consolidating an alliance.

The new US presidency is faced with a very complicated puzzle to solve in the Indo-Pacific, with China and India as the main players. Generally speaking, of the three powers, only Beijing has successfully managed the post-pandemic status [3], while Delhi and Washington continue to face both a health and economic crisis. All of this may affect the India-US relationship, especially on trade[4], but although Biden has yet to demonstrate his strategy in the region, the relationship between the two powers looks set to go from strength to strength[5]. However, although the US wants to pursue a policy of multilateral alliances and deepen its relationship with India, the Biden administration will have to take into account a number of difficulties before it can talk about an alliance as such.

Biden began to move in this direction from the outset. First up was February's meeting of QUAD[6], which some see as a mini-NATO[7] for Asia, where issues of vaccine distribution in Asia (aiming to distribute one trillion doses by 2022), freedom of navigation in the region's seas, North Korea's denuclearisation and democracy in Myanmar were discussed. In addition, the UK seems to be taking a greater interest in the region and in this dialogue group . On the other hand, in mid-March there was a meeting in Alaska[8] between Chinese and US diplomats (led respectively by Yang Jiechi, director of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission, and Antony Blinken, Secretary of State), in which both countries harshly reproached each other's policies. Washington remains firm in its interests, although open to a certain partnership with Beijing, while China insists on rejecting any interference in what it considers to be its internal affairs. Finally, it is worth mentioning that Biden seems to be willing to organise a summit of democracies[9] in his first year in office.

Following contacts also in Alaska between the Chinese and US defence chiefs, Pentagon chief Austin Lloyd[10] visited India to stress the importance of Indo-US cooperation. In addition, early April saw France's participation in the La Pérouse[11] naval exercises in the Bay of Bengal, raising the possibility of a QUAD-plus involving not only the four original powers but also other countries.

The Indo-Pacific, remember, is the present and the future of the International Office due to its economic importance (its main actors, India, China and the USA, represent 45% of the world's GDP), demographic importance (it is home to 65% of the world's population) and, as we will see throughout this article, geopolitical importance[12].

US-China-India relations

The Biden administration seems to be continuing along the same lines as the Trump administration, as the objectives have not changed. What has changed is the approach to the subject matter, which in this case is none other than the containment of China and freedom of navigation in the region, albeit on the basis of a strong commitment to multilateralism. As George Washington's new successor said at his inauguration[13], the United States wants to resume its leadership, but in a different way from the previous Administration; that is, through a strong policy of alliances, moral leadership and a strong defence of values such as dignity, human rights and the rule of law.

The new presidency sees China as a rival to be reckoned with[14], as does the Trump Administration, but it does not see this as a zero-sum game, since, although it openly declares itself to be against Xi's actions, it opens the door to dialogue[15] on issues such as climate change or healthcare. Generally speaking, in line with what has been seen in New tensions in the Asia-Pacific[16], the United States is committed to a multilateralism that seeks to reduce tension. It should be remembered that the United States advocates the defence of free navigation and the rule of law, as well as democracy in a region in which its influence is being eroded by the growing weight of China.

A good understanding of the state of US-China-India relations goes back to 2005[17], when everything seemed to be going well. As far as the Sino-Indian relationship was concerned, the two nations had resolved their disputes over the 1998 nuclear tests, their presence in regional fora was growing, and it seemed that the issue of cross-border disputes was beginning to be settled. For its part, the United States enjoyed good trade relations with both countries. However, shifting patterns in the global Economics , driven by the rise of China, the 2008 financial crisis in the US, and India's inability to maintain its growth rate upset this balance. Donald Trump's tightening stance contributed to this. However, some argue that the breakdown of the post-Cold War order in the Asia-Pacific began with the Obama administration's 'pivot to Asia'[18]. To this must be added the minor frictions China has had with both nations.

Briefly, it is worth mentioning that there are border problems between India and China[19] that have been flaring up again since 2013. India, in turn, is opposed to Chinese hegemony; it does not want to be subjugated by Beijing and is clearly committed to multilateralism. Finally, there are problems regarding maritime dominance because the Strait of Malacca is at capacity. Moreover, Delhi claims the Adaman and Nicobar Islands, on the Malacca access route, as its own. Moreover, as India is now well below China's military and economic power[20] - the balance that existed between the two powers in 1980 is broken - it is trying to hinder Beijing in order to contain it.

The United States has ideological subject friction with China, due to the authoritarian nature of Xi Jinping's regime[21], and commercial friction, in a dispute[22] that Beijing is trying to take advantage of to reduce US influence in the region. In the middle of this conflict is India, which supports the United States because, although it does not seem to want to be completely against China[23], it rejects a Chinese regional hegemony[24].

According to the CEBR's latest report [25], China will overtake the United States as a global power in 2028, earlier than previous projections, in part because of its handling of the coronavirus emergency: it was the only major country to avoid a crisis after the first wave. On the other hand, the US has lost the battle against the pandemic; economic growth between 2022-2024 is expected to be 1.9% of GDP and to slow to 1.6% in the following years[26], while China, according to report , is expected to grow at 5.7% between 2021-2025[27].

For China the pandemic has been a way of signalling its place in the world[28], a way of warning the United States that it is ready to take over as leader of the international community. This has been compounded by China's belligerent attitude in the Asia-Pacific region, as well as its hegemonic growth in the region and trade projects with Africa and Europe. All of this has led to imbalances in the region that implicate Washington's QUAD moves. Recall that, despite its declining role as a power, the US is interested in freedom of navigation for both commercial and military reasons[29].

China's economic rise has thus led to a worsening of the relationship between Washington and Beijing[30]. Moreover, while Biden is committed to cooperation on the pandemic and climate change, there is talk in some quarters of American politics of inevitable competition between the two countries[31].

The Degree of the US-India alliance

In line with the above, we can see that we are in a delicate situation after the change in the White House. January and February have been months of small moves by the US and India, which have not left China indifferent. Although the Sino-US relationship has benefited both sides since its inception (1979)[32], with trade between the two countries growing by 252% since then, the reality is that trust levels are now at rock bottom, with more than 100 dialogue mechanisms suspended between them. Therefore, although conflict is not foreseeable, tension is predicted to rise as, far from being able to cooperate in broad areas, only light and limited cooperation seems feasible at the moment. At the same time, it should be remembered that China is very much affected by the Malacca Dilemma[33], which is why it is seeking other access to the Indian Ocean, giving rise to territorial disputes with India, with whom it already has the territorial problem of Ladakh[34]. In the midst of this Thucydides Trap[35], in which China seems to threaten to overtake the United States, Washington has been moving closer to New Delhi.

Consequently, both countries have been developing a strategic partnership [36], based essentially on security and defence, but which the United States seeks to extend to other areas. It is true that Delhi's problems are in the Indian Ocean and Washington's in the Pacific; however, both have China[37] as a common denominator. Their relationship, moreover, is strongly marked by the aforementioned "tripartite crisis"[38 ] (health, economic and geopolitical).

Despite the intense cooperation between Washington and New Delhi, there are two different views on thispartnership. While the US claims that India is a very important ally, sharing the same political system and an intense trade relationship[39], India prefers a less strict alliance. Traditionally, Delhi has conveyed a policy of non-alignment[40] in international affairs. Indeed, while India does not want Chinese supremacy in the Indo-Pacific, neither does it want to align itself directly against Beijing, with whom it shares more than 3,000 km of border. Nonetheless, Delhi sees a great need for cooperation with Washington on subject security and defence. Indeed, some argue that India needs the US more than ever.

Although Washington began to review the US Global Posture Strategy last February, everything suggests that the Biden Administration will continue Trump's line on partnership with India as a way of containing China. However, while Washington speaks of India as its ally, Delhi is somewhat reticent, speaking of an alignment[41] rather than an alliance. Although the reality we live in is far from that of the Cold War[42], this new containment[43] in which Delhi is sought as a base, support and banner, is materialised in the following:

(i) Intensive cooperation on subject Security and Defence

There are different forums and agreements here. First, the aforementioned QUAD[44]. This new multilateral cooperation alliance that began to take shape in 2006[45] agreed at its March meeting on the development of its vaccine diplomacy, with India at the centre, in order to counteract Beijing's successful international campaign in this field. In fact, there was a commitment to spend 600 million to deliver 1 billion vaccines[46] by 2022. The idea is that Japan and the US will finance the operation[47], while Australia will provide the logistics. India, however, is committed to greater multilateralism in the Indo-Pacific, giving entrance to countries such as the UK and France[48], which already participated in the last Raisina Dialogues together with QUAD. Other issues such as the denuclearisation of Korea, the restoration of democracy in Myanmar and climate change were also discussed at meeting [49].

India seeks to contain China, but without provoking a direct confrontation with China[50]. In fact, Beijing has intimated that if things go further, it is not only India that knows how to play Realpolitik. Let us recall that New Delhi will chair this year's meeting with the BRICS. Moreover, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation will host joint military exercises between China and Pakistan, a country with a complex relationship with India.

On the other hand, during his March trip to India, the Pentagon chief[51] discussed with his counterpart Rajnath Singh increased military cooperation, as well as issues related to logistics, exchange information, possible opportunities for mutual attendance and the defence of free navigation. Lloyd said he did not object to Australia and Korea participating as permanent members in the Malabar exercises. Since 2008, military subject trade between Delhi and Washington has totalled $21 billion[52]. In addition, $3,000 has recently been spent on drones and other aerial equipment for reconnaissance and surveillance missions.

A week later this meeting, two Indian and one US ship conducted a maritime exercise of subject PASSEX[53] as a way of consolidating the synergies and interoperability achieved in last November's Malabar exercise.

accredited specialization subject In this context, a special mention should be made of the 2+2 dialogue platform and the aforementioned scholarship (agreement ) ( exchange and Basic and Cooperation for Geospatial Cooperation). The first is a subject of meeting in which the foreign and defence ministers of both countries meet every two years to discuss issues of interest to them. The most recent meeting took place in October 2020[54]. Not only was the scholarship agreed, but the US reaffirmed its support for India on its territorial issues with China. Other memoranda of understanding were also signed on nuclear energy and climate issues.

The scholarship, signed in October 2020 during the final months of the Trump administration, makes it easier for India to better track enemies, terrorists and other subject threats from land or sea. This agreement is intended to consolidate the friendship between the two countries, as well as help India outpace China technologically. This agreement concludes the "troika of foundational pacts" for deep security and defence cooperation between the two countries[55].

Prior to this agreement, the LEMOA (Memorandum of agreement for exchange Logistics) was signed in 2016, and in 2018 the COMCASA (agreement Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement) was signed. The former allows both countries access to each other's instructions for supply and replenishment; the latter allows India to receive systems, information and encrypted communication to communicate with the United States. Both agreements affect land, sea and air forces[56].

(ii) United for Democracy

Washington emphasises that the two powers are very similar, since they share the same political system, and it is emphasised with a certain grandiloquence that they are the oldest and the largest democracy (per issue inhabitants)[57]. Because this presupposes a shared set of values, Washington likes to speak of "likeminded partners"[58].

Tanvi Mandan of the Brookings Institution think tank Tanvi Mandan defends this idea of ideological bonding. The same system of government means that the two countries see each other as natural allies, who think alike and also believe in the value of the rule of law. In fact, in all matters relating to the spread of democracy around the globe, there is strong cooperation between the two nations: for example, supporting democracy in Afghanistan or the Maldives, launching the US-India Global Democracy Initiative, and providing legal and technical assistance on democratic issues to other countries at attendance . Finally, it is worth noting that democracy and its associated values have facilitated the exchange and flow of people from one country to another. As for the economic relationship between the two countries, it has become more viable, given that they are both open economies, share a common language and their legal system has Anglo-Saxon roots.

iii) Growing economic cooperation

partner The United States is India's main trading partner, with which it has a significant surplus[59]. Trade between the two has grown by 10% annually over the last decade, and in 2019 was $115 billion[60]. Around 2,000 US companies are based in India, and some 200 Indian companies are based in the US[61]. There is a Mini-Trade Deal between the two, believed to be signed soon, which aims to deepen this economic relationship. In the context of the pandemic, everything related to the health sector plays an important role[62]. 62] In fact, despite the fact that both countries have recently adopted a protectionist attitude, the idea is to achieve $500 billion in trade.

Divergences, challenges and opportunities for India and the US in the region

Briefly, between the leaders of the two countries there are minor frictions, opportunities and challenges to be nuanced in order to make this relationship a strong alliance. Among the sticking points is India's purchase of S-400 missiles from Russia, which is against CAATSA(Countering America's Adversaries trhough Sanctions Act) [64], for which India may receive a sanction, although in the meeting between Sigh and Lloyd, Lloyd seemed to overlook topic [65]. However, it remains to be seen what happens once the missiles arrive in Delhi. There are also minor divergences on freedom of expression, security and civil rights, and how to engage with non-democratic countries[66]. Among the challenges that both countries must take into account is the possible loss of support in some quarters of US policy for the relationship with India. This is due to India's actions in Kashmir in August 2019, the protection of religious freedom and attention to dissent. On the other hand, there has been no shortage of weakening of democratic norms, immigration restrictions and violence against Indians[67].

Lastly, let us remember that both are facing a profound health and therefore economic crisis, the resolution of which will be decisive in relation to competition with Beijing[68]. The crisis has affected the bilateral relationship since, although trade in services has remained stable (around 50 billion), trade in goods declined from 92 to 78 billion between 2019 and 2020, increasing India's trade deficit[69].

Finally, it is worth mentioning the opportunities. First, both countries can develop democratic resilience in the Indo-Pacific as well as in a rules-based international order[70]. In security and defence, there are also opportunities such as the UK and France's entrance as allies in the region, for example by seeking both countries' entry into the Malabar exercise or France's chairmanship of the Indian Ocean Naval Symposiumin 2022[71]. Although the medium-term trend deadline is for cooperation between the US and India, skill with Russia will be a growing threat[72], so cooperation between the US, India and Europe is very important.

It also opens up the possibility of cooperation in MDA (Maritime Warning Environment) and ASW (Anti-Submarine Warfare) mechanisms, as the Indian Ocean is of general importance to several countries due to the value of its energy transport routes. The possibility of cooperation through the use of the US P-8 "Poseidon" aircraft is opened up. Despite disputes over the Chagos archipelago, India and the US should take advantage of the agreements they have over islands such as the Andaman and Diego Garcia to carry out these activities[73]. Therefore, India should use the regional bodies and groups of work to cooperate with European countries and the US[74].

Europe seems to be gaining increasing importance because of the possibility of entering the Indo-Pacific game through QUAD Plus. European countries are very much in favour of multilateralism, defending freedom of navigation and the role of rules in regulating it. While it is true that the EU has recently signed a trade agreement with China - the IAC - increasing the European presence in the region takes on greater importance, as Xi's authoritarianism and his actions in Tibet, Xinjiang, or central China are not to the liking of European countries[75].

Lastly, it is worth remembering that there are some voices that speak of a decline or weakening of globalisation[76], especially after the coronavirus epidemic[77], so reviving multilateral exchanges through joint action becomes a challenge and an opportunity for both countries. In fact, it is believed that protectionist tendencies, at least in the Sino-Indian relationship, will continue in the short term deadline , despite intense economic cooperation[78].

Conclusion

The geopolitical landscape in the Indo-Pacific is complex to say the least. Chinese expansionism clashes with the interests of the other major regional power, India, which, while avoiding confrontation with Beijing, takes a dim view of its neighbour's actions. In a bid for multilateralism, and with its sights set on its regional waters, threatened by the Malacca Dilemma, India seems to be cooperating with the United States, but sticking to regional forums and groups to make its position clear, while seeming to open the door to European countries, whose interest in the region is growing, despite the recent trade agreement signed with China.

On the other hand, the United States is also threatened by Chinese expansionism and sees the moment of its rival's economic overtaking approaching, which the coronavirus crisis may even have brought forward to 2028. In order to avoid this status, the Biden Administration has opted for multilateralism at the regional level and is deepening its relationship with India, beyond the military aspect. Washington seems to have understood that US hegemony in the Indo-Pacific is far from being real, at least in the medium term deadline, so that only a cooperative and integrating attitude can be adopted. On the other hand, in the midst of this supposed retreat from globalisation, we see how Washington, together with India, and probably halfway through deadline with Europe, are defending the Western values that govern the international sphere, i.e. the defence of human rights, the rule of law and the value of democracy.

There are two factors at play here. On the one hand, India does not want to see an order imposed by any subject, either American or Chinese, hence its reluctance to confront Beijing directly and its preference to expand the QUAD. On the other hand, the United States seems to perceive that it is at a delicate moment, as its competition with China goes beyond the mere substitution of one power for another. Washington is still a traditional power that, for its presence in the Indo-Pacific, has relied primarily on military power, while China has based the extension of its influence on the establishment of strong trade relations that go beyond the belligerent logic of the Cold War. Hence, the United States is seeking to form a front with India and its European allies that goes beyond military cooperation.

REFERENCES

[1] The QUAD (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue) is a dialogue group formed by the United States, India, Japan and Australia. Its members share a common vision of Indo-Pacific security that runs counter to China's; they advocate multilateralism and freedom of navigation in the region.

[2] scholarship (Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement). Treaty signed by India and the United States in October 2019 to improve security in the Indo-Pacific region. Its goal is the exchange of tracking, tracing and intelligence systems.

[3]Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, "Trilateral Perspective". Chinawatch. Connecting Thinkers... http://www. chinawatch.cn/a/202102/05/WS60349146a310acc46eb43e2d.html,(accessed 5 February 2021),

[4] Tanvi Madan, "India and the Biden Administration: Consolidating and Rebalancing Ties," in Tanvi Madan, "India And The Biden Administration: Consolidating And Rebalancing Ties",. German Marshal Found of the United States. https://www.gmfus.org/blog/2021/02/11/india-and-biden-administration-consolidating-and-rebalancing-ties,(accessed 11 February 2021).

[5]DarshanaBaruah, Frédéric Grére, and Nilanthi Samaranayake, "diary 2021: A Blueprint For U.S.-Europe-India Cooperation", US-India cooperation on Indo-Pacific Security. GMF India Trilateral Forum. Pg:1. https://www.gmfus.org/blog/2021/02/16/us-india-cooperation-indo-pacific-security, (accessed 16 February 2021).

[6] "'QUAD' Leaders Pledge New Cooperation on China, COVID-19, Climate". Aljazeera.com. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/12/quad-leaders-pledge-new-cooperation-on-china-covid-19-climate (accessed March 2021).

[7] Mereyem Hafidi, "Biden Renews 'QUAD' Alliance Despite Pressure From Beijing". Atalayar. https://atalayar.com/content/biden-renueva-la-alianza-de-%E2%80%98QUAD%E2%80%99-pesar-de-las-presiones-de-pek%C3%ADn.(accessed February 2021).

[8] "`Grandstanding`: US, China trade rebukes in testy talks". Aljazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/19/us-china-top-diplomats-trade-rebukes-in-testy-first-talks (accessed March 2021).

[9] Joseph R. Biden, "Why America Must Lead Again". Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again (accessed February, 2021).

[10] Maria Siow. "India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind". South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3126091/india-receives-us-defence-secretary-lloyd-austin-china-its-mind.(accessed 19 March 2021).

[11] Seeram Chaulia, "France and sailing toward the 'QUAD-plus'". The New Indian Express. https://www. newindianexpress.com/opinions/2021/apr/06/france-and-sailing-toward-the-QUAD-plus-2286408.html (accessed April 4, 2021).

[12] Juan Luis López Aranguren. "Indo-Pacific: The new order without China at the centre. The Indo-Pacific as a new global geopolitical axis. Global Affairs Journal. P.:2. https://www.unav.edu/web/global-affairs/detalle/-/blogs/indo-pacifico-el-nuevo-orden-sin-china-en-el-centro?_33_redirect=%2Fen%2Fweb%2Fglobal-affairs%2Fpublicaciones%2Finformes.(accessed April 2021).

[13] Biden, "Remarks By President Biden On America's Place In The World | The White House...".

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/02/04/remarks-by-president-biden-on-americas-place-in-the-world/

[14] Ibid.

[15] Derek Grossman, 'Biden's China Reset Is Already On The Ropes'. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Biden-s-China-reset-is-already-on-the-ropes.(accessed 14 March 2021).

[16] Ramón Barba Castro, 'New tensions in the Asia-Pacific in a scenario of electoral change'. Global Affairs and Strategic Studies. https://www.unav.edu/web/global-affairs/detalle/-/blogs/nuevas-tensiones-en-asia-pacifico-en-un-escenario-de-cambio-electoral-en-eeuu.(accessed, April 2021).

[17] Sankaran Kalyanaraman, "Changing Pattern Of The China-India-US Triangle". Manohar Parrikar Institute For Defence Studies And Analyses. https://www.idsa.in/idsacomments/changing-pattern-china-india-us-triangle-skalyanaram (accessed March 2021).

[18] Pang Zhongying, 'Indo-Pacific Era Needs US-China Cooperation, Not Great Power Conflict'. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3125926/indo-pacific-needs-us-china-cooperation-not-conflict-QUAD (accessed 19 March 2021).

[19] Sankaran Kalayanamaran, "Changing Pattern of the China-India-US Triangle".

[20] Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, "Trilateral Perspective".

[21] Joseph R. Biden, "Remarks By President Biden On America's Place In The World

[22]Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, "Trilateral Perspective".

[23] Maria Siow, "India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind".

[24]Tanvi Madan, "India and the Biden Administration: Consolidating And Rebalancing Ties".

[25] CEBR (Centre for Economics and Business Research) is an organisation dedicated to the economic analysis and forecasting of companies and organisations. linkhttps://cebr.com/about-cebr/. Every year, this organisation produces an annual report graduate World Economic League Table¸which analyses the position of each country in the world in terms of the state of its Economics. The latest edition(World Economic League Table 2021), published on 26 December 2020, presents a prediction of the state of the world's Economics in 2035, in order to know who will be the world's leading economic powers. (CEBR, "World Economic League Table 2021". Centre for Economics and Business Research (12th edition), https://cebr.com/reports/world-economic-league-table-2021/ (accessed March 2021).

[26] Ibid., 231.

[27] Ibid., 71.

[28] Vijay Gokhale, "China Doesn't Want a New World Order. It Wants This One". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/04/opinion/china-america-united-nations.html(accessed April 2021).

[29] Mereyem Hafidi, "Biden renews 'QUAD' alliance despite pressure from Beijing.

[30] Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, "Trilateral Perspective".

[31] Ibid.

[32] Wang Huiyao, "More cooperation, less competition". Chinawatch. Connecting Thinkers. http://www.chinawatch.cn/a/202102/05/WS6034913ba310acc46eb43e28.html(accessed March 2021).

[33] Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, "Trilateral Perspective".

[34] DarshanaBaruah, Frédéric Grére, and Nilanthi Samaranayake, "US-India cooperation on Indo-Pacific Security". Page 5.

[35] Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, "Trilateral Perspective".

[36] Ibid.

[37] DarshanaBaruah, Frédéric Grére, and Nilanthi Samaranayake, "US-India cooperation on Indo-Pacific Security". Page 5.

[38] Tanvi Madan, "India and the Biden Administration: Consolidating And Rebalancing Ties".

[39] Tanvi Madan, "Democracy and the US-India relationship". Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/democracy-and-the-us-india-relationship/ (accessed March 2021)

[40] Maria Siow, "India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind".

[41] Bilal Kuchay, "India, US sign key military deal, symbolizing closer ties". Aljazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/11/2/india-us-military-deal(accessed March 2021)

[42] Wang Huiyao, "More cooperation, less competition".

[43] Alex Lo, "India-the democratic economic giant that disappoints". South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3126342/india-democratic-economic-giant-disappoints(accessed 21 March 2021).

[44] Simone McCarthy, "QUAD summit: US, India, Australia and Japan counter China's 'vaccine diplomacy' with pledge to distribute a billion doses across Indo-Pacific". South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3125344/QUAD-summit-us-india-australia-and-japan-counter-chinas.(accessed 13 March 2021).

[45] MereyemHafidi, "Biden renews 'QUAD' alliance despite pressure from Beijing.

[46] Simone McCarthy, "QUAD summit: US, India, Australia and Japan counter China's 'vaccine diplomacy' with pledge to distribute a billion doses across Indo-Pacific".

[47] Aljazeera, "'QUAD' leaders pledge new cooperation on China, COVID-19, climate".

[48]DarshanaBaruah, Frédéric Grére, and Nilanthi Samaranayake, "US-India cooperation on Indo-Pacific Security". Page 2.

[49]Simone McCarthy, "QUAD summit: US, India, Australia and Japan counter China's 'vaccine diplomacy' with pledge to distribute a billion doses across Indo-Pacific".

[50] Maria Siow, "India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind".

[51] "US defense secretary Lloyd Austin says US considers India to be a great partner". Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/us-defense-secretary-lloyd-austin-says-us-considers-india-to-be-a-great-partner-101616317189411.html.(accessed 21 March 2021).

[52] Maria Siow, "India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind".