Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

High levels of corruption and impunity in the region make it difficult to eradicate millionaire bribes in public procurement contracts

The confession of the construction and engineering company Odebrecht, one of the most important in Brazil, of having delivered large sums as bribes to political leaders, parties and public officials for the awarding of works in various countries in the region has been the biggest corruption scandal in the history of Latin America. The B budget increase during the "golden decade" of raw materials occurred in a framework of little improvement in the effectiveness of the rule of law and control of corruption, which led to high levels of illicit deviations in public contracts.

article / Ximena Barría [English version].

Odebrecht is a Brazilian company that conducts business in multiple industries through several operating sites. It is engaged in areas such as engineering, construction, infrastructure and energy, among others. Its headquarters in Brazil are located in the city of Salvador de Bahia. The business operates in 27 countries in Latin America, Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Over the years, the construction company has participated in public works contracts in most Latin American countries.

In 2016, the U.S. Justice department published a research denouncing that the Brazilian company had bribed public officials in twelve countries, ten of them Latin American: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Dominican Republic and Venezuela. The research was developed from the confession made by Odebrecht's own top executives once they were discovered.

The company provided officials in these countries with millions of dollars in exchange for obtaining public works contracts and benefiting from the payment for their execution. The business agreed to submit millions of dollars to political parties, public officials, public candidates or persons related to the Government. Its purpose was to have a competitive advantage that would allow it to retain public business in different countries.

In order to cover up these illicit capital movements, business created fictitious corporations in places such as Belize, the Virgin Islands and Brazil. The business developed a secret financial structure to cover up these payments. The research of the U.S. Justice department established that bribes in the aforementioned countries totaled US$788 million (almost half in Brazil alone). Using this illegal method, contrary to all business and political ethics, Odebrecht obtained the commissioning of more than one hundred projects, the execution of which generated profits of US$ 3,336 million.

Lack of an effective judiciary

This matter, known as the Odebrecht case, has created consternation in Latin American societies. Its citizens consider that in order for acts of this nature subject not to go unpunished, countries must have greater efficiency in the judicial sphere and take more accelerated steps towards a true Rule of Law.

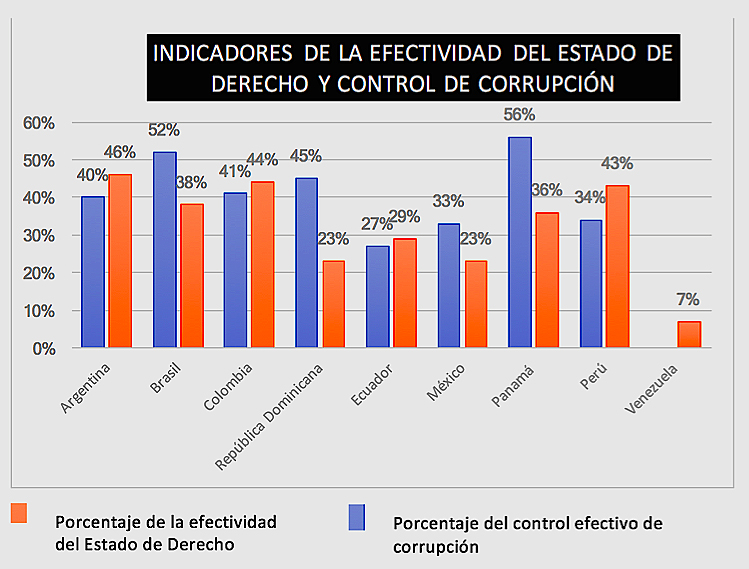

From agreement with World Bank indicators, none of the ten Latin American countries affected by this bribery network reaches 60% of effectiveness of the rule of law and corruption control. This would explain the success of the Brazilian construction company in its bribery policy.

|

source: World Bank, 2016 |

Judicial independence and its effectiveness is essential for the resolution of facts of these characteristics. The proper exercise of justice shapes a proper rule of law, preventing the occurrence of illicit acts or other political decisions that may violate it. Although this is the ideal, the countries involved in the Odebrecht case do not fully comply with this due judicial independence.

Indeed, according to the Global Competitiveness Report for 2017-2018, most of the affected countries obtain a leave grade regarding the independence of their courts, which indicates that they lack an effective judiciary to judge the alleged people involved in this case. This is the case, for example, with Panama and the Dominican Republic, ranked 120th and 127th, respectively, in terms of judicial independence, out of a list of 137 countries.

One of the problems suffered by the Judicial Branch of the Republic of Panama is the high issue of files handled by the Supreme Court of Justice. This congestion makes it difficult for the Supreme Court to work effectively. The high number of processed files doubled between 2013 and 2016: the conference room Criminal Court processed 329 files in 2013; in 2016 there were 857. Although the Panamanian Judicial Branch has improved its budget, that has not represented a qualitative increase in its functions. These difficulties could explain the Court's decision to reject an extension of the research, even though this could mean some impunity. In 2016, there were only two detainees for the Odebrecht case. In 2017, of the 43 defendants who could be involved in the acceptance of bribes valued at US$60 million, only 32 were prosecuted.

The Dominican Republic is also at a similar status . According to a survey of 2016, only 38% of Dominicans trust the judicial institution. This low percentage may have been contributed to by the fact that active members of political parties were elected to serve as Supreme Court judges, something that tarnishes the credibility of the judiciary and its independence. In 2016, Dominican courts only inquired about one person, when the U.S. Supreme Court estimated that the Brazilian business had given $92 million in political bribes, one of the highest amounts outside Brazil. In 2017, the Supreme Court of the Dominican Republic ordered the release from prison of 9 out of 10 allegedly involved in the case due to insufficient evidence.

Need for greater coordination and reform

In October 2017, public prosecutors from Latin America met in Panama City to share information on money laundering, especially in relation to the Odebrecht case. Officials expressed the need to leave no case unpunished, thereby contributing to solving one of the biggest political, economic and judicial problems in the region. Some prosecutors reported having suffered threats in their investigations. All of them valued positively the meeting, as it highlighted the need for greater fiscal coordination and legislative harmony in Latin America. However, it is important to note that the Dominican Republic was absent from meeting.

Any awareness of public ministries in Latin America is essential given the correlation observed between the countries affected by Odebrecht bribes and their poor ranking in indexes provided by different international organizations and centers of research. Ineffective rule of law and lack of control of corruption enable companies like Odebrecht to succeed in their bribery policy to gain a competitive advantage.

The shortcomings of the judicial systems in countries such as Panama and the Dominican Republic, in particular, may make it possible for public officials to go unpunished for crimes committed. In addition, the Odebrecht case, of great magnitude in the region, could further congest judicial activity if effective reforms are not made in each country.

The constant expansion of soy production within the MERCOSUR countries exceeds 50% of total world production

While many typically associate South American commodities with hydrocarbons and minerals, soy or soybean is the other great commodity of the region. Today, soy is the agricultural product with the highest commercial growth rate in the world. China and India lead world consumption of this oleaginous plant and its byproducts, thus making South America a strategic supplier. Soy profitability has encouraged the expansion of crop production, especially in Brazil and Argentina, as well as in Paraguay, Bolivia and Uruguay. However, such expansion comes at an environmental cost; such as recent deforestation in the Amazon and the Gran Chaco.

ARTICLE / Daniel Andrés Llonch [English version] [Spanish version].

Soy has been cultivated in Asian civilizations for thousands of years; today its cultivation is also widespread in other parts of the world. It has become the most important oilseed for human consumption and animal feed. Of great nutritional properties, due to its high protein content, soybeans are sold both in grain and in their oil and flour derivatives.

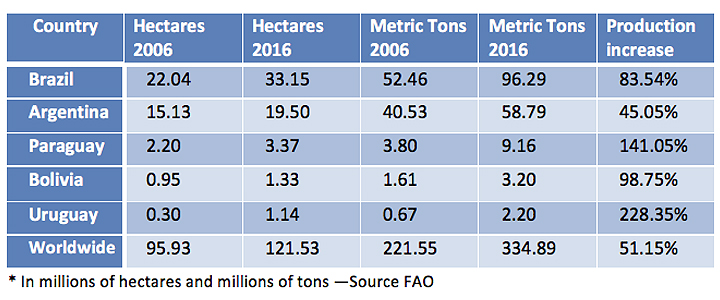

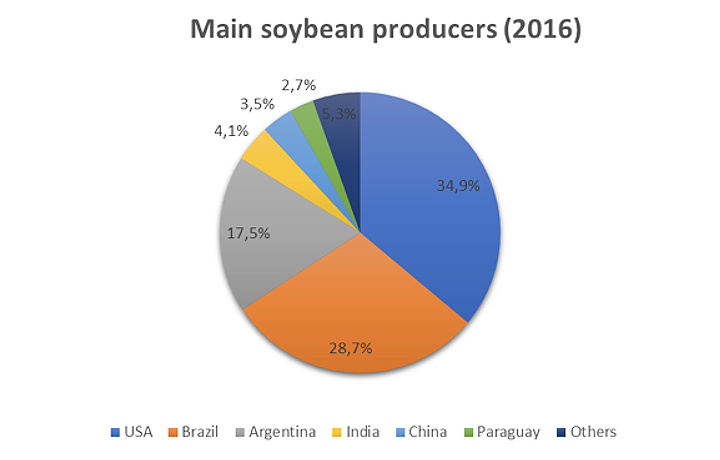

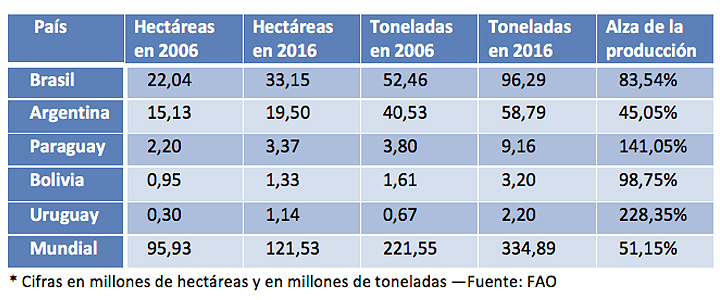

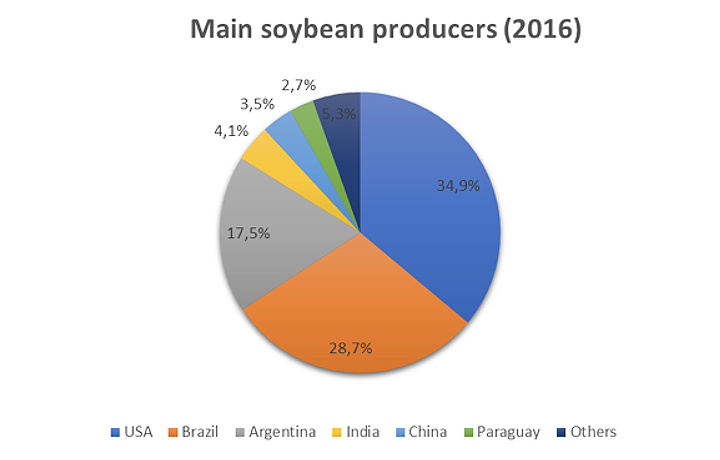

Among the eleven largest soybean producers, five are in South America: Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia and Uruguay. In 2016, these countries were the origin of 50.6% of world production, whose total reached 334.8 million tons, according to FAO data. The first producer was the United States (34.9% of world production), followed by Brazil (28.7%) and Argentina (17.5%). India and China follow the list, although what is significant about this last country is its large consumption, which in 2016 forced it to import 83.2 million tons. Much of these import needs are covered from South America. Furthermore, the South American production focuses on the Mercosur nations (in addition to Brazil and Argentina, also Paraguay and Uruguay) and Bolivia.

The strong international demand and the high relative profitability of soybean in recent years has fueled the expansion of the cultivation of this plant in the Mercosur region. The price boom for raw materials, which also involved soy, led to benefits that were directed to the acquisition of new land and equipment, which allowed producers to increase their scale and efficiency.

In Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Paraguay the area planted with soybeans represents the majority (it constitutes more than 50% of the total area sown with the five most important crops in each country). If we add Uruguay, where soybean has enjoyed a later expansion, we have that the production of these five South American countries has gone from 99 million tons in 2006 to 169.7 million in 2016, which constitutes a rise of 71%. In addition, the production of Brazil and Bolivia has almost doubled their production, somewhat exceeded by Paraguay and Uruguay, where it has tripled. In the decade, this South American area has gone from contributing 44.7% of world production to 50.6%. At that time, the cultivated area increased from 40.6 million hectares to 58.4 million.

|

Countries

As the second largest producer of soybeans in the world, Brazil reached 96.2 million tons in 2016 (28.7% of the world total), with a cultivation area of 33.1 million hectares. Its production has been in a constant increasement, so that in the last decade the volume of the harvest has increased by 83.5%. The jump has been especially B in the last four years, in which Brazil and Argentina have experienced the highest growth rate of the crop, with an annual average of 936,000 and 878,000 hectares, respectively, according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Argentina is the second largest producer of Mercosur, with 58.7 million tons (17.5% of world production) and a cultivated area of 19.5 million hectares. Soybeans began to be planted in Argentina in the mid-70s, and in less than 40 years it has had an unprecedented advance. This crop occupies 63% of the areas of the country planted with the five most important crops, compared to 28% of the area occupied by corn and wheat.

Paraguay, for its part, had a harvest of 9.1 million tons of soybeans in 2016 (2.7% of world production). In recent seasons, soy production has increased as more land is allocated for cultivation. According to the USDA, in the last two decades, the land dedicated to the cultivation of soybeans has constantly increased by 6% annually. Paraguay currently has 3.3 million hectares of land dedicated to this activity, which constitutes 66% of the land used for the main crops.

As far as Bolivia is concerned, soybeans are grown mainly in the Santa Cruz region. According to the USDA, it represents 3% of the country's Gross Domestic Product, and employs 45,000 workers directly. In 2016, the country harvested 3.2 million tons (0.9% of world production), in an area of 1.3 million hectares.

Soybean plantations occupy more than 60 percent of Uruguay's arable land, where soybean production has been increasing in recent years. In fact, it is the country where production has grown the most in relative terms in the last decade (67.7%), reaching 2.2 million tons in 2016 and a cultivated area of 1.1 million hectares.

|

Increase of the demand

The production of soy represents a very important fraction in the agricultural GDP of the South American nations. The five countries mentioned together with the United States make up 85.6% of global production, so they are the main suppliers of the growing global demand.

This production has experienced a progressive increase since its insertion in the market, with the exception of Uruguay, whose product expansion has been more recent. In the period between 1980 and 2005, for example, the total world demand for soybean expanded by 174.3 million tons, or what is the same, 2.8 times. In this period, the growth rate of global demand accelerated, from 3% annually in the 1980s to 5.6% annually in the last decade.

In all the South American countries mentioned, the cultivation of soy has been especially encouraged, because of the benefits that it entails. Thus, in Brazil, the largest regional producer of oilseed, soybean provides an estimated income of 10,000 million dollars in exports, representing 14% of the total products marketed by the country. In Argentina, soybean cultivation went from representing 10.6% of agricultural production in 1980/81 to more than 50% in 2012/2013, generating significant economic benefits.

The outlook for growth in demand suggests a continuation of the increase in production. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that global production will exceed 500 million tons in 2050, which doubles the volume harvested in 2010 and clearly, much of that demand will have to be met from South America.

The constant expansion of the crop in Mercosur countries has led them to exceed 50% of world production.

Soybean is the agricultural product with the highest commercial growth in the world. The needs of China and India, major consumers of the fruit of this oleaginous plant and its derivatives, make South America a strategic granary. Its profitability has encouraged the extension of the crop, especially in Brazil and Argentina, but also in Paraguay, Bolivia and Uruguay. Its expansion is behind recent deforestation in the Amazon and the Gran Chaco. After hydrocarbons and minerals, soybeans are the other major commodity in South America subject .

article / Daniel Andrés Llonch [English version].

Soybean has been cultivated in Asian civilizations for thousands of years; today its cultivation is also widespread in other parts of the world. It has become the most important oilseed grain for human consumption and animal feed. With great nutritional properties due to its high protein content, soybeans are marketed both in grain and in their oil and meal derivatives.

Of the eleven largest soybean producers, five are in South America: Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia and Uruguay. In 2016, these countries were the origin of 50.6% of world production, whose total reached 334.8 million tons, according to FAO's data . The first producer was the United States (34.9% of world production), followed by Brazil (28.7%) and Argentina (17.5%). India and China follow on the list, although what is significant about the latter country is its large consumption, which in 2016 forced it to import 83.2 million tons. A large part of these import needs are covered from South America. South American production is centered in the Mercosur nations (in addition to Brazil and Argentina, also Paraguay and Uruguay) and Bolivia.

Strong international demand and the high relative profitability of soybeans in recent years have fueled the expansion of soybean cultivation in the Mercosur region. The commodity price boom, in which soybeans also participated, led to profits that were directed to the acquisition of new land and equipment, allowing producers to increase their scale and efficiency.

In Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Paraguay, the area planted with soybean is the majority (it constitutes more than 50% of the total area planted with the five most important crops in each country). If to group we add Uruguay, where soybean has enjoyed a later expansion, we have that the production of these five South American countries has gone from 99 million tons in 2006 to 169.7 million in 2016, which is an increase of 71.2% (Brazil and Bolivia have almost doubled their production, somewhat surpassed by Paraguay and Uruguay, a country where it has tripled). In the decade, this South American area has gone from contributing 44.7% of world production to total 50.6%. In that time, the cultivated area increased from 40.6 million hectares to 58.4 million hectares.

|

Countries

As the second largest soybean producer in the world, Brazil reached in 2016 a production of 96.2 million tons (28.7% of the world total), with a crop area of 33.1 million hectares. Its production has known a constant increase, so that in the last decade the volume of the crop has increased by 83.5%. The jump has been especially B in the last four years, in which Brazil and Argentina have experienced the highest rate of increase of the crop, with an annual average of 936,000 and 878,000 hectares, respectively, from agreement with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) department .

Argentina is the second largest producer in Mercosur, with 58.7 million tons (17.5% of world production) and a cultivated area of 19.5 million hectares. Soybean began to be planted in Argentina in the mid 1970s, and in less than 40 years it has made unprecedented progress. This crop occupies 63% of the country's areas planted with the five most important crops, compared to 28% of the area occupied by corn and wheat.

Paraguay, meanwhile, had a 2016 harvest of 9.1 million tons of soybeans (2.7% of world production). In recent seasons, soybean production has increased as more land is allocated for its cultivation. From agreement with the USDA, over the last two decades, land devoted to soybean cultivation has steadily increased by 6% annually. There are currently 3.3 million hectares of land in Paraguay dedicated to this activity, which constitutes 66% of the land used for the main crops.

In Bolivia, soybeans are grown mainly in the Santa Cruz region. According to the USDA, it accounts for 3% of the country's Gross Domestic Product, and employs 45,000 workers directly. In 2016, the country harvested 3.2 million tons (0.9% of world production), on an area of 1.3 million hectares.

Soybean plantations occupy more than 60 percent of the arable land in Uruguay, where soybean production has been increasing in recent years. In fact, it is the country where production has grown the most in relative terms in the last decade (67.7%), reaching 2.2 million tons in 2016 and a cultivated extension of 1.1 million hectares.

|

Increased demand

Soybean production represents a very important fraction of the agricultural GDP of South American nations. The five countries mentioned above, together with the United States, account for 85.6% of global production, making them the main suppliers of the growing world demand.

This production has experienced a progressive increase since its insertion in the market, with the exception of Uruguay, whose expansion of the product has been more recent. In the period between 1980 and 2005, for example, total world soybean demand expanded by 174.3 million tons, or 2.8 times. During this period, the growth rate of global demand accelerated from 3% per year in the 1980s to 5.6% per year in the last decade.

In all the South American countries mentioned above, soybean cultivation has been especially encouraged, due to the benefits it brings. Thus, in Brazil, the largest regional producer of the oleaginous grain, soybeans contribute revenues estimated at 10 billion dollars in exports, representing 14% of the total products marketed by the country. In Argentina, soybean cultivation went from representing 10.6% of agricultural production in 1980/81 to more than 50% in 2012/2013, generating significant economic benefits.

The outlook for growth in demand suggests that production will continue to rise. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that global production will exceed 500 million tons in 2050, double the volume harvested in 2010. Much of this demand will have to be met from South America.

▲Trilateral Summit of Russia, Turkey and Iran in Sochi, November 2017 [Presidency of Turkey].

ANALYSIS / Albert Vidal and Alba Redondo [English version].

Turkey's response to the Syrian Civil War (SCW) has gone through several phases, instructed by changing circumstances, both domestic and foreign. From supporting Sunni rebels with questionable organizational affiliations, to being a target of the Islamic State (IS), to surviving a coup attempt in 2016, a constant theme underpinning Turkish foreign policy decisions has been the Kurdish question. Despite an initially aggressive anti-Assad stance at the onset of the Syrian war, the success and growing strength of the Kurdish opposition as a result of their role in the anti-IS coalition has significantly reordered Turkish foreign policy priorities.

Relations between Turkey and Syria have been riven with difficulties over the past century. The Euphrates River, which originates in Turkey, has been one of the main causes of confrontation, with the construction of dams by Turkey limiting water flow to Syria, causing losses in agriculture and negatively impacting the Syrian economy. This issue is not confined to the past, as the ongoing GAP project (Project of the Southeast of Anatolia) threatens to further compromise water supplies to both Iraq and Syria through the construction of 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric dams.

Besides resource issues, the previous support of Hafez al-Assad to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in the 1980s and '90s severely strained relations between the two countries, with conflict narrowly avoided with the signing of the Adana Protocol in 1998. Another source of conflict between the two countries relates to territorial claims made by both nations over the disputed Hatay province; still claimed by Syria, but administered by Turkey, which incorporated it into its territory in 1939.

Notwithstanding the above-mentioned issues between the nations - to name but a few - Syria and Turkey enjoyed a good relationship in the decade prior to the Arab Spring. The response to the Syrian regime's reaction to the uprisings by the international community has been mixed, and Turkey was no less unsure about how to position itself; eventually opting to support the opposition. As a result, Turkey offered protection on its territories to the rebels, as well as opening its borders to Syrian refugees This decision signaled the initial stage of decline in relations between the two countries, and the situation significantly worsened after the downing of a Turkish jet on 22 June 2012 by Syrian forces. Border clashes ensued, but without direct intervention of the Turkish Armed Forces.

From a foreign policy perspective, there were two primary reasons for the reversal of Turkey's non-intervention policy. The first was an increasing string of attacks by the Islamic State (IS) in the summer of 2015 in Suruç, the Central Station in Ankara, and the Atatürk Airport in Istanbul. The second, and arguably more important one, was Turkish fears of the creation of a Kurdish proto-state in neighboring Syria and Iraq. This led to the initiation of Operation Shield of the Euphrates (also known as the Jarablus Offensive), considered one of the first instances of direct military intervention by Turkey in Syria since the SCW began, with the aim of securing an area in the North of Syria free of control of IS and the Party of the Democratic Union (PYD) factions. The Jarablus Offensive was supported by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations (nations' right to self-defense), as well as a number United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions (Nos. 1373, 2170, 2178) corresponding to the global responsibility of countries to fight terrorism. Despite being a success in meeting its objectives, the Jarablus Offensive ended prematurely in March 2017, without Turkey ruling out the possibility of similar future interventions.

Domestically, military intervention and a more assertive stance by Erdogan was aimed at garnering public support from both Turkish nationalist parties - notably, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and Great Unity Party (BBP) - as well as the general public for proposed constitutional changes that would lend Erdogan greater executive powers as president. Along those lines, a distraction campaign abroad was more than welcome, given the internal unrest following the coup attempt in July 2016.

Despite Turkey's growing assertiveness in neighboring Syria, Turkish military intervention does not necessarily signal strength. On the contrary, Erdogan's effective invasion of northern Syria occurred only after a number of events transpired in neighboring Syria and Iraq that threatened to undermine Turkish objectives both at home and abroad. Thus, the United States' limited intervention, and the failure of rebel forces to successfully uproot the Assad regime, meant the perpetuation of the terrorist threat but, more importantly, the continued strengthening of the Kurdish factions that have, throughout, constituted one of the most effective fighting force against IS. In effect, the success of the Kurds in the anti-IS coalition had gained it global recognition akin to that earned by most nation states; recognition that came with funding and the provision of arms. An armed Kurdish constituency, increasingly gaining legitimacy for its anti-IS efforts, is arguably the primary reason for both Turkish military intervention today, but also, a seemingly shifting stance vis-à-vis the question of Assad's position in the aftermath of the SCW.

|

▲Erdogan visits the command center for Operation Olive Branch, January 2018 [Presidency of Turkey]. |

Shifting Sand: Turkey's Changing Stance vis-à-vis Assad

While Turkey aggressively supported the removal of Assad at the outset of the SCW, this idea has increasingly come to take a back seat to more important foreign policy issues regarding Turkey and its neighboring states, Syria and Iraq. In fact, recent statements by Turkish officials openly acknowledge the longevity and resilience of the government of Assad, a move that strategically leaves the door open to future reconciliation between the two parties, and reinforces a by now widely supported view that Assad is likely to be part and parcel of any future Syria deal. Thus, on20th January 2017, Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey, Mehmet Şimşek said: "We cannot keep saying that Assad should leave. A deal without Assad is not realistic."

This relaxation of rhetoric towards Assad coincides with a Turkish pivot towards Assad's allies in the conflict (Iran and Russia) in its attempts to achieve a resolution of the conflict, yet the official Turkish position regarding Assad lacks consistency, and appears to be more dependent on prevailing circumstances. Recently, a war of words initiated by Erdogan with the Syrian president played out in the average, in which the former accused Assad of being a terrorist. Syrian foreign minister Walid Muallem, for his part, responded by accusing Erdogan of being responsible for the bloodshed of the Syrian people.

On January 2, 2018, Syrian shells were fired into Turkish territory by forces loyal to Assad. The launch provoked an immediate response from Turkey. On January 18, Mevlüt Çavusoglu, the Turkish foreign minister, announced that his country intends to carry out an air intervention in the Syrian regions of Afrin and Manbij. A few days later, Operation Olive Branch was launched under the pretext of creating a "security zone" in Afrin (in Syria's Aleppo province) yet has been almost entirely focused on uprooting what Erdogan claims are Kurdish "terrorists", may of which belong to US-backed Kurdish factions that have played a crucial role in the anti-IS coalition. The operation was allegedly initiated in response to US plans of creating a 30,000 Syrian Kurds border force. As Erdogan commented in a recent speech:"A country we call an ally is insisting on forming a terror army on our borders. What can that terror army target but Turkey? Our mission is to strangle it before it's even born." This has significantly strained relations between the two countries, and triggered an official response from NATO in an attempt to avoid full frontal confrontation between the NATO allies in Manbij.

The US is seeking a balance between the Kurds and Turkey in the region, but it has maintained its formal support for the SDF. Nevertheless, according to analyst Nicholas Heras, the US will not help the Kurds in Afrin due to the fact that its intervention is only active in counter-IS mission areas; geographically starting from Manbij (thus Afrin not falling under US military protection).

The Impact of the Syrian Conflict on Turkey's International Relations

The Syrian conflict has strongly impacted on Turkish relations with a host of international actors, of which the most central to both Turkey and the conflict are Russia, the US, the European Union and Iran.

The demolition of a Russian SU-24 aircraft in 2015 caused a deterioration of relations between Russia and Turkey. However, thanks to the Turkish president's apologies to Putin in June 2016, relations were normalized and a new era of cooperation between both countries has seemingly begun. This cooperation reached a high point in September of the same year when Turkey bought an S-400 defense missile system from Russia, despite warnings from its NATO allies. Further, the Russian company ROSATOM has planned the construction of a nuclear plant in Turkey worth $20 million. Thus, it can be said that cooperation between the two nations has been strengthened in the military and economic spheres.

Despite an improvement in relations however, there remain to be significant differences between both countries, particularly regarding foreign policy perspectives. On the one hand, Russia sees the Kurds as important allies in the fight against IS; consequently perceiving them to be essential to participants in post-conflict resolution (PCR) meetings. On the other, Turkey's priority is the removal of Assad and the prevention of Kurdish federalism, which translates into its rejection of including the Kurds in PCR talks. Notwithstanding, relations appear to be quite strong at the moment, and this may be due to the fact that the hostility (in the case of Turkey, growing) of both countries towards their Western counterparts trumps their disagreements regarding the Syrian conflict.

The situation regarding Turkish relations with the US is more ambiguous. By virtue of belonging to NATO, both countries share important working ties. However, even a cursory glance at recent developments suggests that these relations have been deteriorating, despite the NATO connection. The main problem between Washington and Ankara has been the Kurdish question, since the US supports the Popular Protection Units (YPG) militias in the SCW, yet the YPG are considered a designated terrorist outfit in Turkey. How the relationship will evolve is yet to be seen, and essentially revolves around both parties reaching an agreement regarding the Kurdish question. Currently, the near showdown in northern Syria is proving to be a stalemate, with Turkey clearly signaling its unwillingness to back down on the Kurdish issue, and the US risking serious face loss should it succumb to Turkey's demands. Support to the Kurds has typically been predicated on their role in the anti-IS campaign yet, with the campaign dying down, the US finds itself in a bind as it attempts to justify its continued presence in Syria. This presence is crucial to maintaining a footprint in the region and, more importantly, preventing the complete political domination of the political scene by Russia and Iran.

Beyond the Middle East scene, the US's refusal to extradite Fetullah Gülen, a staunch enemy that, according to Ankara, was one of the instigators of the failed coup of 2016, has further strained relations. According to a survey by the Pew Research Center, only 10% of Turks trust President Donald Trump. In turn, Turkey recently stated that its agreements with the US are losing their validity. Erdogan has stressed that the dissolution of ties between both countries will seriously affect the legal and economic sphere. Furthermore, the Turk Zarrab has been found guilty in a New York trial for helping Iran evade sanctions through enabling a money-laundering scheme that filtered through US banks. This has been a big issue for Turkey, because one of the accused had ties with Erdogan's AKP party. However, Erdogan has cast the trial as a continuation of the coup attempt, and has organized a average campaign to spread the idea that Zarrab was one of the authors of the conspiracy against Turkey.

With regards the EU, relations have also soured, despite Turkey and the EU enjoying strong economic ties. As a result of Erdogan's "purge", the rapidly deteriorating situation of freedoms in Turkey have strained relations with Europe. In November 2016, the European Parliament voted to suspend EU accession negotiations with Turkey, due to human rights issues and the state of the rule of law in Turkey. By increasingly adopting the practices of an autocratic regime, Turkey's access to the EU will be essentially impossible. In a recent meeting between the Turkish and French presidents, French president Emmanuel Macron emphasized continuing EU-Turkey ties, yet suggested that there was no realistic chance of Turkey joining the EU in the near future.

Since 2017, following Erdogan's victory in the constitutional referendum in favor of changing over from a parliamentary to a presidential system, access negotiations to the EU have effectively ceased. In addition, various European organs that deal with human rights issues have placed Turkey on "black" lists, based on their assessment that the state of democracy in Turkey is in serious jeopardy thanks to the AKP.

Another issue in relation to the Syrian conflict between the EU and Turkey relates to the refugee issue. In 2016, the EU and Turkey agreed to transfer 6 billion euros to support the Turkish reception of hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees. Although this seemed like the beginning of fruitful cooperation, tensions have continued to increase due to Turkey's limited capacity to host refugees. The humanitarian crisis in Syria is unsustainable: more than 5 million refugees have left the country and only a small segment has been granted sufficient resources to restart their lives. This problem continues to grow day by day, and more than 6 million Syrians have been displaced within its borders. Turkey welcomes more than 3 million Syrian refugees and consequently, it influences on Ankara, whose policies and position have been determined to a large extent by this crisis. On January 23, President Erdogan claimed that Turkey's military operations in Syria will end when all the Syrian refugees in Turkey can return safely to their country. Humanitarian aid work has been underway for civilians in Afrin, where the offensive against Kurdish YPG militia fighters has been launched.

With regards the relationship between Iraq and Turkey, in November 2016, when Iraqi forces entered Mosul against the IS, Ankara announced that it would send the army to the Iraqi border, in order to prepare for important developments in the region. Turkey's defense minister added that he would not hesitate to act if Turkey's network line was crossed. He received a response from Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar Al-Abadi, who warned Turkey not to invade Iraq. Despite this, in April 2017, Erdogan suggested that in future stages, Operation Euphrates Shield would extend to Iraqi territory stating, "a future operation will not only have a Syrian dimension, but also an Iraqi dimension. Al Afar, Mosul and Sinjar are in Iraq."

Finally, Russia, Turkey and Iran have been cooperating in the framework of the Astana negotiations for peace in Syria, despite having somewhat divergent interests. In a recent call between Iranian President Rouhani and Erdogan, the Turkish president expressed his hope that the protests in Iran, which occurred at the end of 2017, would end. The relations between the two countries are strange: in the SCW, Iran supports the Syrian government (Shia), whereas Turkey supports the Syrian (Sunni) opposition. A similar thing occurred in the 2015 Yemen intervention, where Turkey and Iran supported opposing factions. This has led to disputes between the leaders of both countries, yet such tensions have been eased since Erdogan paid a visit to Iran to improve their relationship. The Qatar diplomatic crisis has similarly contributed to this dynamic, since it placed Iran and Turkey against Saudi Arabia and in favor of Qatar. Although there is an enduring element of instability in relations between both countries, their relationship has been improving in recent months, since Ankara, Moscow and Tehran have managed to cooperate in an attempt to overcome their differences for finding a solution to the Syrian conflict.

What next for Turkey in Syria?

Thanks to the Astana negotiations, a future pact for peace in the region seems possible. The de-escalation zones are a necessary first step to preserve some areas of the region from the violence of war, as the Turkish strategic plan has indicated from the beginning. This being said, the outcome is complicated by a number of factors, of which the continuing strength of Kurdish factions remains a significant bone of contention, and source of conflict, for power brokers managing post-conflict transition.

There are two primary factors that have clearly impacted Turkey's foreign policy decisions vis-à-vis the Syrian conflict. The first relates to the long and complex history of Turkey with its Kurdish minorities, and its fixation on preventing the Kurds from achieving a degree of territorial autonomy that would embolden Turkish Kurds and threaten Turkey's territorial integrity. Turkey has unilaterally attacked positions of the Kurdish opposition, including those supported by a NATO ally (the US), effectively demonstrating the lengths to which it is planning to go to ensure that the Kurds are not part of a post-civil war equation. All this fuels uncertainty and increases chances of further conflict erupting in Syria, and elsewhere.

The second relates to the changing nature of governance in Turkey, with a clear shift away from the Western, democratic model to a more authoritarian, quasi-theocratic one; looking more to Russia and Iran as political allies. In its pivot to the East, Turkey plays a careful balancing game, taking into consideration the conflicting goals that both itself and its new friends, Russia and Iran, hold regarding the political outcome in Syria. What current events indicate, however, is that Turkey seems to be moving more towards a compromise over the Assad issue, in return for flexibility in dealing with the Kurdish element of the anti-IS coalition that it deems a threat to its national security.

At the time of writing, Turkey and the US appear to be at a stalemate regarding particularly the US-backed SDF. Erdogan has stated that its operation in Afrin will be followed by a move toward Manbij, and, as such, an agreement to clearly delineating zones where both countries are militarily active is being negotiated under NATO auspices. How long such a partitioning under the pretext of an anti-IS coalition can last before further conflict erupts is uncertain. What seems to be likely however is that one of two possible scenarios must transpire to avoid the potential breakout of war in the Middle East among the major powers.

Either an agreement is reached regarding the future role of the SDF and other Kurdish factions, on which the Turks can agree. Or else the US strategically withdraws its support to the Kurds, based on the mandate that the alliance was limited to the two parties' joint efforts in the anti-IS coalition. In the latter case, the US risks losing its political and military leverage via the Kurds in the region, as well as losing face with their Kurdish allies; a move that could have serious strategic repercussions for US involvement in the region.

▲Trilateral summit of Russia, Turkey and Iran in Sochi in November 2017 [Turkish Presidency].

ANALYSIS / Albert Vidal and Alba Redondo [English version].

Turkey's response to the Syrian Civil War (SCW) has gone through several phases, conditioned by the changing circumstances of the conflict, both domestically and internationally: from giving support to Sunni rebels with questionable affiliations, to being one of the targets of the Islamic State (ISIS), to a failed coup attempt in 2016, and always conditioning its foreign policy decisions on the Kurdish issue. Despite an initially aggressive stance against Assad at the beginning of the Syrian war, the success and growing strength of the Kurdish civil service examination , such as result of its role in the anti-ISIS coalition, has significantly influenced Turkey's foreign policy .

Relations between Turkey and Syria have been fraught with difficulties for the past century. The Euphrates River, which originates in Turkey, has been one of the main causes of confrontation between the two countries. Turkey's construction of dams limits the flow of water to Syria, causing losses in its agriculture and generating a negative impact on the Syrian Economics . This problem is not limited to the past, as currently the project GAP (project of Southeastern Anatolia) threatens to further compromise the water supply of Iraq and Syria through the construction of 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric dams in southern Turkey.

In addition to disputes over natural resources, Hafez al-Assad's support for the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) in the 1980s and 1990s greatly hindered relations between the two countries. However, conflict was avoided altogether with the signature of the protocol of Adana in 1998. Another source of discord between Syria and Turkey has been the territorial claims made by both nations over the province of Hatay, still claimed by Syria, but administered by Turkey, which incorporated it into its territory in 1939.

Despite the above issues, Syria and Turkey enjoyed a good relationship during the decade leading up to the Arab Spring and the revolutions of the summer of 2011. The international response to the Syrian regime's reaction to the uprisings was mixed, and Turkey was unsure of what position to take until, in the end, it chose to support the rebel civil service examination . Thus, Turkey offered protection on its territory to the rebels and opened its borders to Syrian refugees. This decision signaled the initial stage of the decline in Syrian-Turkish relations, but the status significantly worsened after the downing of a Turkish plane on June 22, 2012 by Syrian forces. This resulted in border clashes, but without the direct intervention of the Turkish Armed Forces.

From a foreign policy perspective, there were two main reasons for reversing Turkey's non-intervention policy. The first reason was a growing series of Islamic State (ISIS) attacks in July 2015 in Suruc, Central Station in Ankara and Atatürk Airport in Istanbul. The second, and arguably the most important reason, was Turkey's fear of the creation of a Kurdish proto-state in its neighboring countries: Syria and Iraq. This led to the launch of Operation Euphrates Shield (also known as the Jarablus Offensive), considered one of Turkey's first direct military actions in Syria since the SCW began. The main goal was to secure a area in northern Syria free from control of ISIS and Democratic Union Party (PYD) factions. The Jarablus Offensive was supported by article 51 of the UN Charter (the right of nations to self-defense), as well as several UN Security committee resolutions (Nos. 1373, 2170, 2178) pertaining to the global responsibility of countries to fight terrorism. Despite being successful in achieving its objectives, the Jarablus offensive ended prematurely in March 2017, without Turkey ruling out the possibility of similar future interventions.

Internally, Erdogan's military intervention and assertive posturing aimed to gain public support from Turkish nationalist parties, especially the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and the Grand Unity Party (BBP), as well as general public backing for the constitutional changes then being proposed. That would give Erdogan greater executive powers as president. Consequently, a foreign distraction campaign was more than welcome, given the growing domestic unrest and general discontent, following the coup attempt in July 2016.

Despite Turkey's assertiveness sample towards Syria, Turkish military intervention does not indicate strength. On the contrary, Erdogan's actual invasion of northern Syria occurred in the wake of disputes (between Syria and Iraq) that threatened to undermine Turkish objectives, both at home and abroad. Thus, limited United States (US) interference and the failure of rebel forces to topple the Assad regime meant the perpetuation of the terrorist threat; and, more importantly, the continued strengthening of Kurdish factions, which posed the most effective force against ISIS. Indeed, the Kurds' success in the anti-ISIS coalition had helped them gain worldwide recognition similar to that of most nation-states; recognition that meant increased financial support and increased provision of weapons. A Kurdish region, armed and gaining legitimacy for its efforts in the fight against ISIS, is undoubtedly the main reason for Turkish military intervention. In any case, the growing Kurdish influence has resulted in Turkey's shifting and ambiguous attitude towards Assad throughout the SCW.

|

▲visit of Erdogan to the command of Operation Olive Branch, January 2018 [Presidency of Turkey]. |

Turkey's changing stance on Assad

While Turkey aggressively supported Assad's ouster at the beginning of the SCW, this stance has increasingly taken a back seat to other more important issues of Turkey's foreign policy with its neighboring states, Syria and Iraq. Indeed, recent statements by Turkish officials openly acknowledge the resilience of the Assad government, a fact that opens the door to future reconciliation between the two sides. These statements also reinforce a very profuse view, according to which, Assad will be a piece core topic in any future agreement on Syria. Thus, on January 20, 2017, Turkey's Deputy Prime Minister Mehmet Şimşek said,"We cannot keep saying that Assad should go. A agreement without Assad is not realistic."

This easing of rhetoric towards Assad coincides with a positive shift in Turkey's relations with the Syrian regime's allies in the conflict (Iran and Russia), in its attempts to bring about a resolution of the conflict. However, the official Turkish position towards Assad lacks consistency, and appears to be highly dependent on circumstances.

Recently, a war of words initiated by Erdogan with the Syrian president took place, in which the Turkish president accused Assad of being a terrorist. Moreover, Erdogan rejected any subject negotiations with Assad on the future of Syria. For his part, Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Muallem responded by accusing Erdogan of being manager of the bloodshed of the Syrian people. On January 2, 2018, forces loyal to Assad fired shells towards Turkish territory. Such a launch prompted an immediate response from Turkey. On January 18, Mevlüt Çavusoglu (Turkish Foreign Minister) announced that his country intended to carry out an air intervention in the Syrian regions of Afrin and Manbij.

A few days later, Operation Olive Branch was launched, under the pretext of creating a "security zone" in Afrin (in Syria's Aleppo province); although it has focused almost entirely on expelling what Erdogan calls Kurdish "terrorists," which are actually composed of Kurdish factions backed by the U.S. These Kurdish groups have played a crucial role in the anti-ISIS coalition. The operation was reportedly launched in response to U.S. plans to create a border force of 30,000 Syrian Kurds. Erdogan stated in a recent speech :"A country we call an ally insists on forming a terror army on our borders. Who can that terrorist army attack if not Turkey? Our mission statement is to strangle it before it is born." This has significantly worsened relations between the two countries, and triggered an official NATO response, in an attempt to avoid confrontation between NATO allies in Manbij.

The US is seeking a balance between the Kurds and Turkey in the region, but has maintained its formal support for the SDF. However, according to analyst Nicholas Heras, the US will not help the Kurds in Afrin, as it will only intervene in the areas of mission statement against ISIS; starting from Manbij and towards the East (thus Afrin is not under US military protection).

Impact of the Syrian conflict on Turkey's International Office

The Syrian conflict has had a strong impact on Turkish relations with a wide range of international actors; of which the most important for both Turkey and the conflict are Russia, the United States, the European Union and Iran.

The downing of a Russian SU-24 aircraft in 2015 led to a deterioration of relations between Russia and Turkey. However, thanks to the Turkish president's apology to Putin in June 2016, relations normalized, ushering in a new era of cooperation between the two countries. This cooperation reached its pinnacle in September of the same year when Turkey purchased an S-400 defense missile system from Russia, despite warnings from its NATO allies. In addition, the Russian business ROSATOM has planned to build a nuclear power plant in Turkey worth $20 billion. Thus, the partnership between the two nations has been strengthened in the military and economic spheres.

However, despite the rapprochement, there are still significant differences between the two countries, particularly with regard to foreign policy perspectives. On the one hand, Russia sees the Kurds as important allies in the fight against ISIS; and considers them essential members in the post-conflict peaceful resolution (PCR) meetings. On the other hand, Turkey's priority is to bring democracy to Syria and prevent Kurdish federalism, which translates into its refusal to include the Kurds in PCR talks. Nevertheless, the ties between Turkey and Russia seem to be quite strong at the moment. This may be due to the fact that the (in Turkey's case, increasing) hostility of both countries towards their Western counterparts outweighs their differences regarding the Syrian conflict.

The relationship between Turkey and the United States is more ambiguous. As important members of NATO, both countries share important ties from work. However, looking at recent developments, one can see how these relations have been deteriorating. The main problem between Washington and Ankara has been the Kurdish issue. The US supports the People's Protection Units (YPG) militias in the SCW, however, the YPG is considered a terrorist group by Turkey. It is not yet known how their relationship will evolve, but possibly both sides will reach a agreement regarding the Kurdish issue. As of today (January 2018), the confrontation in northern Syria is at a stalemate. On the one hand, Turkey does not intend to give in on the Kurdish issue, and on the other hand, the US would lose its prestige as a superpower if it decided to succumb to Turkish demands. Support for the Kurds has traditionally been based on their role in the anti-ISIS campaign. However, as the campaign winds down, the US is finding itself in a bind trying to justify its presence in Syria in any way it can. Its presence is crucial to maintain its influence in the region and, more importantly, to prevent Russian and Iranian domination of the contested theater.

The US refusal to extradite Fethullah Gülen, a bitter enemy who, according to Ankara, was one of the instigators of the failed 2016 coup, has further strained their relations. According to a survey by the Pew Research Center, only 10% of Turks trust President Donald Trump. In turn, Turkey recently declared that its agreements with the U.S. are losing validity. Erdogan subryaed that the dissolution of ties between the two countries would seriously affect the legal and economic sphere. In addition, Turkey's Zarrab was convicted in a trial in New York, for helping Iran evade sanctions by enabling a money laundering scheme, which was filtered through US banks. This has been a big problem for Turkey, as one of the defendants had ties to Erdogan's AKP party. However, Erdogan has called the trial a continuation of the coup attempt, and has dealt with potential criticism by organizing a media campaign to spread the idea that Zarrab was one of the perpetrators of the conspiracy against Turkey in 2016.

With respect to the European Union, relations have also deteriorated, despite the fact that Turkey and the EU have strong economic ties. As result of Erdogan's "purge" after the failed coup, the continued deterioration of freedoms in Turkey has strained relations with Europe. In November 2016, the European Parliament voted in favor of fail EU accession negotiations with Turkey, justifying its decision on the abuse of human rights and the decline of the rule of law in Turkey. By increasingly adopting the practices of an autocratic regime, Turkey's accession to the EU is becoming impossible. In a recent meeting between the Turkish and French presidents, French President Emmanuel Macron emphasized the ties between the EU and Turkey, but suggested that there was no realistic chance of Turkey joining the EU in the near future.

Since 2017, after Erdogan's victory in the constitutional referendum in favor of changing the system (from a parliamentary to a presidential system), EU accession negotiations have ceased. In addition, several European bodies, which deal with human rights issues, have placed Turkey on a "black" list, based a assessment, according to which the state of democracy in Turkey is in serious danger due to the AKP.

Another topic related to the Syrian conflict between the EU and Turkey is refugees. In 2016, the EU and Turkey agreed to transfer €6 billion to support Turkish reception of hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees. While this appeared to be the beginning of a fruitful cooperation, tensions have continued to rise due to Turkey's limited capacity to host such issue of refugees. The humanitarian crisis in Syria is unsustainable: more than 5 million refugees have left the country and only a small issue of them have received sufficient resources to restart their lives. This problem continues to grow day by day, and more than 6 million Syrians have been displaced within its borders. Turkey hosts, as of today, more than 3 million Syrian refugees and, consequently, Ankara's policies have result been greatly influenced by this crisis. On January 23, President Erdogan stated that Turkey' s military operations in Syria would end when all Syrian refugees in Turkey could return safely to their country. The humanitarian financial aid is being sent to civilians in Afrin, where Turkey launched the latest offensive against Kurdish YPG militiamen.

Regarding the relationship between Iraq and Turkey, in November 2016, when Iraqi forces arrived in Mosul to fight against the Islamic State, Ankara announced that it would send the army to the Iraqi border, to prepare for possible developments in the region. The Turkish Defense Minister added that he would not hesitate to act if Turkey's red line was crossed. This received an immediate response from Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar Al-Abadi, who warned Turkey not to invade Iraq. Despite this, in April 2017, Erdogan suggested that in future stages, Operation Euphrates Shield would be extended to Iraqi territory: "a future operation will not only have a Syrian dimension, but also an Iraqi dimension. Al Afar, Mosul and Sinjar are in Iraq."

Finally, Russia, Turkey and Iran have cooperated in the framework Astana negotiations for peace in Syria, despite having somewhat divergent interests. In a recent call between Iranian President Rouhani and Erdogan, the Turkish president expressed his hope that the protests in Iran, which occurred in late 2017, will end. The relations between the two countries are strange: in the SCW, Iran supports the Syrian (Shiite) government, while Turkey supports the Syrian (Sunni) civil service examination . Something similar happened in the 2015 intervention in Yemen, where Turkey and Iran supported the opposing factions. This has led to disputes between the leaders of the two countries, however, such tensions have eased since Erdogan made a visit to Iran to improve their relationship. The Qatar diplomatic crisis has also contributed to this dynamic, as it positioned Iran and Turkey against Saudi Arabia and in favor of Qatar. Although there is an enduring element of instability in relations between the two countries, their relationship has been improving in recent months as Ankara, Moscow and Tehran have managed to cooperate in an attempt to overcome their differences to find a solution to the Syrian conflict.

What lies ahead for Turkey in Syria?

Thanks to the negotiations in Astana, a future agreement peace in the region seems possible. The "cessation of hostilities" zones are a necessary first step, to preserve some areas from the violence of war, as outlined in the Turkish strategic plan from the beginning. That said, the result is complicated by a number of factors: the strength of the Kurdish factions is a major element of discord, as well as a source of conflict for the powerful who will manage the post-conflict transition.

There are two main factors that have clearly impacted Turkey's foreign policy decisions regarding the Syrian conflict. The first has to do with the long and complex history of Turkey and its Kurdish minorities, as well as its obsession with preventing the Kurds from achieving a Degree territorial autonomy. If achieved, this would embolden the Turkish Kurds and threaten Turkey's territorial integrity. Turkey unilaterally attacked positions of the Kurdish civil service examination , including some backed by a NATO ally (the US), thus demonstrating how far it is capable of going to ensure that the Kurds are not part of the solution at the end of the civil war. All this produces uncertainty and increases the chances of new conflicts in Syria.

The second factor is related to the changing nature of the government in Turkey, with a move away from the Western-democratic model towards a more authoritarian and quasi-theocratic model , taking Russia and Iran as political allies. In its pivot to the east, Turkey maintains a fragile balance, considering that its objectives differ from those of its new friends (Russia and Iran), with respect to the political result in Syria. Recent developments indicate, however, that Turkey seems to be reaching a agreement on the Assad issue, in exchange for more flexibility in dealing with the Kurdish issue (part of the anti-ISIS coalition), which it considers a threat to its national security.

Currently, in January 2018, the relationship between Turkey and the U.S. appears to be at an impasse, especially in relation to the U.S.-backed group SDF. Erdogan has stated that, after his operation in Afrin, he will continue with a move towards Manbij. Therefore, under NATO auspices, a agreement is being negotiated to clearly delineate the areas in which both countries are militarily active. There is great uncertainty as to how long such partition agreements (under the guise of an anti-ISIS coalition) can last before a new conflict breaks out. However, it seems likely that one of the two possible scenarios will occur to avoid the possible outbreak of war between the great powers in the Middle East.

There are two options. Either a agreement is reached regarding the future role of the SDF and other Kurdish factions, with Turkey's consent, or else the US will withdraw its support for the Kurds, based on the mandate that their alliance was limited to joint fighting in the anti-ISIS coalition. In the latter case, the US risks losing the political and military advantage that the Kurds give it in the region. It also risks losing the confidence of its Kurdish allies, a fact that could have serious strategic repercussions for US involvement in this region.

ESSAY / Marianna McMillan [English version].

I. Introduction

On the 31st of March 2016, Federica Mogherini, the High Representative for Foreign affairs and Security Policy of the European Commission, launched a Cultural Diplomacy Platform to enhance the visibility and understanding of the Union through intercultural dialogue and engagement. By engaging all stakeholders from a bottom-up perspective, the platform forces us to reconsider the context in which it operates, the internal constraints it wishes to address, and lastly, the foreign policy objective it aspires to. However, in order to export a European cultural image abroad with a single, coherent voice, the Union must first address its 'unity in diversity' of national cultures without threatening the national identities of the individual Member States. Therefore, the EU as an international actor and regional organization, based on unity in diversity, has an internal need for intercultural dialogue and negotiation of shared identities (European External Action Service, 2017). Not only to establish conditions favorable to Brussels policies but as an instrument for the EU to counter external, non-traditional security threats - terrorism, populist narratives, cyber insecurity, energy insecurity and identity ambiguity.

This understanding of culture as a potential instrument or means for Europe's soft power is the basis for the analysis of this paper. In doing so, the purpose of the article is to explore the significance of culture relative to soft power and foreign policy as theoretical foundations for understanding the logic of the EU's New Cultural Diplomacy Platform.

II. Unity in diversity through the New Cultural Diplomacy Platform

If the European Union aspires to a "rules based" liberal order founded on cooperation, then to what extent can the EU obtain global influence and domestic unity by preserving its interests and upholding its values, if it lacks both a single voice and a common external policy?

The lack of a single voice is symptomatic of a history of integration based on diversity rather than equality. And the incoherent common external policy refers to the coordination problem, in which the cultural relations remains a competence of the individual Member States and the Common Foreign and Security Policy remains a supranational competence of the EU since the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992 (Banus, 2015:103-105 and Art 6, TFEU).

With the acceleration of globalization, non-traditional security challenges such as cyber warfare, climate change, radicalization, refugee and economic migration and energy insecurity test the EU's idea of a common Foreign Policy between the EU institutions and the individual member states. These threats not only demand a new security paradigm but a new coexistence paradigm, in which security is directed towards radicalization reduction and coexistence is directed towards civil societies based on democratic order and rule of law (European Commission, 2016). For example, regarding the regional integration process, the process sustains itself by promoting narratives of shared cultural heritage. However, growing skepticism towards immigrants following the refugee crisis fosters a conflicting narrative with the wider societal and communitarian narrative projected by the EU - The European Commission (EC), the European External Action Service (EEAS), the European Parliament (EP), and the Council of the European Union. The Union's failure to address the pervasive divisions between member states in issues pertaining to the Brexit negotiation, the financial crisis or international terrorism, further fuel populist narratives and solidify nationalist prejudices against the EU These institutional and structural constraints - diversity and shared competences - reflect the dynamics of the cultural landscape and its unintended consequences on the European Union as a political entity (institutional), the European project as an integration process (unity in diversity) and the European identity as a single voice (social).

In response to a blurring of the distinction between internal constraints and external threats - radicalization, energy and cyber insecurity and populist regimes -, EU High Representative Federica Mogherini established the New Cultural Diplomacy Platform (NCP hereafter) in 2016.

In order to eliminate terminological ambiguity, cultural diplomacy is understood from both a realist "balance of power" approach and a conceptual "reflexive" approach (Triandafyllidou and Szucs, 2017). Whereas the prior refers to an art of dialogue to advance and protect the nation's interest abroad (ex. joint EU cultural events - film festivals, bilateral programs - Supporting the Strengthening of Tunisia's Cultural Sector, creation of European Cultural Houses, Culture and Creativity Programme, average and culture for development in the Southern Mediterranean region, and the NCP). The latter, a more reflexive approach, is a policy in itself, promoting sustainable social and economic development through people-to-people diplomacy (e.g. cultural exchanges - like Erasmus Plus, the Development and Cooperation Instrument and its sub-Programs, the Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR), the ENI Cross Border Cooperation, the Civil Society Facility). By applying it to the EU; on one hand, it contributes to global visibility and influence of the EU through soft power and, on the other hand, it seeks to promote economic growth and social cohesion through civil societies (Trobbiani, 2017: 3-5).

Despite being financed by the Partnership Instrument (PI), which has for its objective the enhancement of the "widespread understanding and visibility of the Union", the EU's NCP is a balance of both the realist and conceptual approach to cultural diplomacy (European Commission, 2016b). As such it is a strategy of resilience that responds to a new reality in which the emergence of non-traditional security threats and a shift in citizens from independent observers to active participants demands a constructive dialogue that engages all the concerned stakeholders - national governments, international organizations and civil societies (Higgot, 2017: 6-8 and European Union, 2016). As a strategy of societal or cultural resilience, resilience is understood in terms of the society's inclusiveness, prosperity and security. According to the Global Strategy of 2016, it aims for pluralism, coexistence and respect by "deepening work on education, culture and youth" (European Union, 2016). In other words, it invests in creative industries, such as Think Tanks, Cultural Institutes or local artists, to preserve a cultural identity, further economic prosperity and enhance soft power.

By seeking global understanding and visibility, the EU's recent interest in International Cultural Relations (ICR) and Culture Diplomacy (CD) reflect the entity's ongoing need for a single voice and a single common external policy. This effort demonstrates the significance of culture in soft politics by highlighting the relationship between culture and foreign policy. Perhaps the more appropriate question is to what extent can Mogherini's NCP convert culture in a tool of soft power? And is such a strategy - ICR and NCP - an effective communication and coordination model before the current internal and external security threats, or will it undermine its narrative?

III. Culture and Soft Power

The shift in the concept of security demands a revisiting of the concept of soft power. In this case, cultural diplomacy must be understood in terms of soft power and soft power must be understood in terms of capacity - capacity to attract and influence. Soft power according to Joseph Nye's notion of persuasion grows out of "intangible power resources": "such as culture, ideology and institutions" (Nye, 1992: 150-170).

The EU as a product of cultural dialogues is a civilian power, a normative power and a soft power. The power of persuasion of the EU relies on its legitimacy and credibility in its institutions (European Union, 2016a and Michalski, 2005: 124-141). For this reason, the consistency between the identity the EU wishes to portray and the practices it should pursue is fundamental to the projection of itself as a credible international actor. This consistency will be necessary if the EU is to fulfill its goal to "enhance unity in diversity". To do otherwise, would contradict its liberal values and solidify the populist prejudices against the EU. Thus, internal legitimacy and credibility as sources of soft power are ultimately dependent on the consistence between the EU's identity narrative and democratic values reflected in its practices (European Union, 2016). Cultural diplomacy responds to the inconsistency by demanding reflection on one hand and enhancing that identity on the other hand. For example, the positive images of Europe through the OPEN Neighborhood communication program helps advance specific geopolitical interests by creating better lasting conditions for cooperation with countries like Algeria, Libya and Syria to the south and Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine to the East. This is relevant to what Nye coined soft power or "co-optive power": "The ability of a country to structure a situation so that other countries develop preferences or define their interests in consistency with its own" (see Nye, 1990: 168). Soft power applied to culture can work both indirectly or directly. It works indirectly when it is independent of government control (e.g. Popular culture) and directly via cultural diplomacy (e.g. NCP). Foreign policy actors - can act as advocates of a certain domestic culture both consciously - e.g. politicians - and unconsciously - e.g. local artists. By doing so they serve as agents for other countries or channels for their soft power.

V. Culture and foreign policy

If soft power grows out of the EU's culture, domestic values and policies then culture is both a foundation and resource of foreign policy (Liland, 1993: 8). First, as a foundation, foreign policy operates within the cultural framework of any given society or society in which it wishes to interact. Thus, necessitating a domestic cultural context capable of being influenced (e.g. the difference in the accession negotiations between Croatia and Turkey and the appeal of economic integration, on one hand, and the ability to adjust human rights policies, on the other hand). And secondly, as a resource, the cultural interchange yields power to the EU. This ability of attitudes, feelings and popular images to influence foreign policy, domestic politics and social life demonstrates culture's ability to be a power resource of its own (Liland, 1993: 9-14 and Walt, 1998). This is significant because cultural interchange will increase as the acceleration of globalization makes communication faster, cheaper and more accessible. And lastly, as part of foreign policy, it diffuses information and obtains favorable opinions in the nation at the receiving end (Liland, 1993:12-13).

Therefore, Cultural Diplomacy at the forefront of European Foreign Policy does not signify the use of culture to substitute the traditional foreign policy goals - geography, power, security, political and economic - but the use of culture to support and legitimize them. In other words, culture is not the primary agent in the process to foreign policy rather the foundation that reinforces, contradicts or explains its content (e.g. Wilsonian idealism in the 1920s can be traced to a domestic culture of "manifest destiny" at the time) (Liland, 1993 and Kim, 2011: 6).

V. Conclusions

The purpose of the article has been to highlight the significance of culture relative to soft power and foreign policy as theoretical foundations for understanding the logic of the EU's New Cultural Diplomacy Platform. By identifying culture as playing an integral role in contributing to social cohesion within the EU and strengthening its influence as a global actor outside the EU, we can deduct culture as a source of soft power and an instrument of foreign policy. But the sources of soft power - culture, political values and foreign policy - are dependent on three conditions: (1) a favorable context; (2) credibility in values and practice; and (3) a perception of legitimacy and moral authority (see Nye, 2006). The EU must first legitimize itself as a coherent actor and moral authority so as to be able to effectively deal with its existential crises (European Union, 2016a: 9 and Tuomioja, 2009).

To do so, it must overcome its institutional and structural constraints by collectively confronting its external non-traditional security threats. This demands a strategy of resilience in which the EU is not a threat to national identity as a cultural, economic and legislative entity (Higgot, 2017: 11-13 and La Porte, 2016).

Various themes relating to culture and soft power, culture and foreign policy and the EU and its internal dynamics are covered in this article, however little has been said on the impact of a "uniform cultural system" and how foreign policy can influence the culture of a society. Culture is not an end in itself nor are the intercultural dialogues and the development on cultural diplomacy. The Union must be cautious to evolving into a dehumanizing bureaucratic structure that favors a standard culture to counter both its internal constraints and external, non-traditional security threats. If democracy is one of the prevailing values of the EU and democracy is a system based on trust in human responsibility, then the EU cultural diplomacy must foster trust rather than impose a standard culture. According to Vaclav Havel, it can do so by supporting cultural institutions respective of the plurality and freedom of culture, such as those fundamental to one's national identity and traditions of the land. In other words, culture must be subsidized to best suit its plurality and freedom as is the case with heritage sites, libraries, museums and public archives - or witnesses to our past (Havel, 1992). By incentivizing historical reflection, cultural diplomacy promotes shared narratives of cultural identities. To do otherwise does not only solidify the populist rhetoric and internal prejudices against the Union but is endemic to cultural totalitarianism, or worse, cultural relativism.

To aspire to a "uniform culture system" through an agreed European narrative would be to trade off pluralism and freedom and consequently contradict, first the nature of culture and secondly, the liberal values in which the Union was founded on.

Bibliography

Banus E. (2015). Culture and Foreign Policy, 103-118.

Arndt, R. T. (2013). culture or propaganda? Reflections on half a century of U.S. cultural diplomacy. Mexican Journal of Foreign Policy, 29-54.

Cull, N. J. (2013). Public diplomacy: Theoretical considerations. Mexican Journal of Foreign Policy, 55-92.

Cummings, Milton C. (2003) Cultural Diplomacy and the United States Government: A Survey, Washingotn, D.C.. Center for Arts and Culture.

European Commission (2016). A new strategy to put culture at the heart of EU international relations. Press release.

European Commission (2016b). Towards an EU strategy for international cultural relations. Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council.

European External Action Service (2017). Culture - Towards an EU strategy for international cultural relations. Joint Communication.

European Union (2016). From Shared Vision to Common Action: The EU's Global Strategic Vision.

European Union (2016b). Towards an EU Strategy for International Cultural Relations. Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council.

European Union (2017) Adminstrative Arrangements developed by the European Union National Institutes for Culture (EUNIC) in partnership with the European Commission Services and the European External Action Service, 16 May (https:// eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/2017-05-16_admin_arrangement_eunic.pdf).

Havel, Vaclav (1992) "On Politics, Morality and Civility in a Time of Transition."Summer Meditations, Knopf.

Higgot, R. (2017). Enhancing the EU's Internatioanl Cultural Relations: The Prospects and Limits: Cultural Diplomacy. Institute for European Studies.

Howard, Philip K. (2011). Vaclav Havel's Critique of the West. The Atlantic.

Kim, Hwajung. (2011) Cultural Diplomacy as the Means of Soft Power in an Information Age.

La Porte and Cross (2016). The European Union and Image Resilience during Times of Crisis: The Role of Public Diplomacy. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 1-26.

Liland, Frode (1993). Culture and Foreign Policy: An Introduction to Approaches and Theory. Institutt for Forsvarstudier, 3-30.

Melissen, J. (2005). The New Public Diplomacy: Between Theory and Practice.

Melissen, J. (2005). The New Public Diplomacy: Between Theory and Practice. In The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations (pp. 3-30). Basinggstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Michalski, Anna (2005). The EU as a Soft Power: The Force of Persuasion. In J. Melissen, The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations (pp. 124-141). New York, N.Y.: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nye, Joseph S. (2004). Soft power: The means to success in world politics. New York: Oublic Affairs.

Nye, Joseph S., (1992) Soft Power, Foreign Policy, Fall, X, pp. 150-170 1990.

Nye, Joseph. S. (2006) Think Again: Soft Power, Foreign Policy.

Richard Higgot and Virgina Proud (2017). Populist Nationalism and Foreign Policy: Cultural Diplomacy and Resilience. Institut fur Auslandsbeziehungen.

Rasmussen, S. B. (n.d.). Discourse Analysis of EU Public Diplomacy: Messages and Practices.

Triandafyllidou, Anna and Tamas Szucs (2017). EU Cultural Diplomacy: Challenges and Opportunities. European University Institute.