Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs World order, diplomacy and governance .

[Mondher Sfar, In search of the original Koran: the true history of the revealed text (New York: Prometheus Books, 2008) 152pp].

REVIEW / Marina G. Reina

Not much has been done regarding research about the authenticity of the Quranic text. This is something that Mondher Sfar has in mind throughout the book, that makes use of the scriptural techniques of the Koran, the scarce research material available, and the Islamic tradition, to redraw the erased story of the transmission of the holy book of Muslims. The same tradition that imposes "a representation of the revelation and of its textual product-which (...) is totally alien to the spirit and to the content of the Quranic text".

The work is a sequencing of questions that arise from the gaps that the Islamic tradition leaves regarding the earliest testimony about the Koran and the biography of Prophet Muhammad. The result is an imprecise or inconclusive answer because it is almost impossible to trace the line back to the very early centuries of the existence of Islam, and due to an "insurmountable barrier" that "has been established against any historical and relativized perception of the Koran (...) to consecrate definitively the new orthodox ideology as the only possible and true one".

As mentioned, Sfar's main sources are those found in the tradition, by which we mean the records from notorious personalities in the early years of the religion. Their sayings prove "the existence in Muhammad's time of two states of the revealed text: a first state and a reworked state that have been modified and corrected". This fact "imperils the validity and identity of Revelation, even if its divine authenticity remains unquestioned."

The synthesis that the author makes on the "kinds of division" (or alterations of the Revelation), reducing them to three from certain ayas in the Koran, is also of notorious interest. In short, these are "that of the modification of the text; that of satanic revelations; and finally, that of the ambiguous nature of the portion of the Revelation". The first one exemplifies how the writing of the Revelation was changed along time; the second is grounded on a direct reference to this phenomenon in the Koran, when it says that "Satan threw some [false revelations] into his (Muhammad's) recitation" (22:52), something that, by the way, is also mentioned in the Bible in Ezekiel 13:3, 6.

Another key point in the book is that of the components of the Koran (the surahs and the ayas) being either invented or disorganised later in time. The manuscripts of the "revealed text" vary in style and form, and the order of the verses was not definitively fixed until the Umayyad era. It is remarkable how something as basic as the titles of the surahs "does not figure in the first known Koranic manuscript", nor was it reported by contemporaries to the Prophet to be ever mentioned by him. The same mystery arises upon the letters that can be read above at the beginning of the preambles in the surahs. According to the Tradition, they are part of the Revelation, whilst the author argues that they are linked to "the process of the formation of surahs", as a way of numeration or as signatures from the scribes. As already mentioned, it is believed that the Koran version that we know today was made in two phases; in the second phase or correction phase surahs would have been added or divided. The writer remarks how a few surahs lack the common preambles and these characteristic letters, which leads to think that these elements were added in the proofreading part of the manuscript, so these organisational signals were omitted.

It may seem that at some points the author makes too many turns on the same topic (in fact, he even raises questions that remain unresolved throughout the book). Nonetheless, it is difficult to question those issues that have been downplayed from the Tradition and that, certainly, are weighty considerations that provide a completely different vision of what is known as the "spirit of the law". This is precisely what he refers to by repeatedly naming the figure of the scribes of the Prophet, that "shaped" the divine word, "and it is this operation that later generations have tried to erase, in order to give a simplified and more-reassuring image of the Quranic message, that of a text composed by God in person," instead of being "the product of a historical elaboration."

What the author makes clear throughout the book is that the most significant and, therefore, most suspicious alterations of the Koran are those introduced by the first caliphs. Especially during the times of the third caliph, Uthman, the Koran was put on the diary again, after years of being limited to a set of "sheets" that were not consulted. Uthman made copies of a certain "compilation" and "ordered the destruction of all the other existing copies". Indeed, there is evidence of the existence of "other private collections" that belonged to dignitaries around the Prophet, of whose existence, Sfar notes that "around the fourth century of the Hijra, no trace was left."

The author shows that the current conception of the Koran is rather simplistic and based on "several dogmas about, and mythical reconstructions of, the history." Such is the case with the "myth of the literal 'authenticity'," which comes more "from apologetics than from the realm of historical truth." This is tricky, especially when considering that the Koran is the result of a process of wahy (inspiration), not of a literal transcription, setting the differentiation between the Kitab ( "the heavenly tablet") and the Koran ("a liturgical lesson or a recitation"). Moreover, Sfar addresses the canonization of the Koran, which was made by Uthman, and which was criticized at its time for reducing the "several revelations without links between them, and that they were not designed to make up a book" into a single composition. This illustrates that "the principal star that dominated the period of prophetic revelation was to prove that the prophetic mission claimed by Muhammad was indeed authentic, and not to prove the literal authenticity of the divine message," what is what the current Muslim schools of taught are inclined to support.

In general, although the main argument of the author suggests that the "Vulgate" version of the Koran might not be the original one, his other arguments lead the reader to deduce that this first manuscript does not vary a lot from the one we know today. Although it might seem so at first glance, the book is not a critique to the historicity of Islam or to the veracity of the Koran itself. It rather refers to the conservation and transmission thereof, which is one of the major claims in the Koran; of it being an honourable recitation in a well-guarded book (56:77-78). Perhaps, for those unfamiliar with the Muslim religion, this may seem insignificant. However, it is indeed a game-changer for the whole grounding of the faith. Muslims, the author says, remain ignorant of a lot of aspects of their religion because they do not go beyond the limits set by the scholars and religious authorities. It is the prevention from understanding the history that prevents from "better understanding the Koran" and, thus, the religion.

The former ECB president takes the helm of Italy with a diary of reforms and a return to Atlanticism.

After years of political instability, in mid-February Italy inaugurated an in principle stronger government headed by Mario Draghi, former president of the European Central Bank. His technical profile , his prestige after eight years in European governance and the formation of a government with a certain national unity character are an opportunity for Italy to overcome the current health and economic crisis and undertake the reforms the country needs.

Mario Draghi, accepting the task of forming a government in February 2021 [Presidency of the Republic].

article / Matilde Romito, Jokin de Carlos Sola

For more than a year, the government of Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte had been strongly contested from within, especially by the disagreements of Italia Viva, the party led by Matteo Renzi, at subject economic. The straw that broke the camel's back was Renzi's civil service examination over Conte's proposed plan for the use of aid from the Recovery Fund set up by the European Union to deal with the crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Conte lost his majority on 13 January following the resignation of three ministers belonging to Italia Viva and on 26 January presented his Withdrawal. On 3 February the President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, entrusted the new government to Mario Draghi, former president of the European Central Bank (ECB), with the task of leading the new government training .

At the start of his mandate, Mario Draghi set out his objectives. He stressed the importance of the country maintaining a certain unity at such a difficult historical moment and indicated that his priority would be to provide more opportunities and to fight against the status quo that prevents the implementation of reforms.

On 17 February, Mario Draghi won the confidence of Parliament, one of the largest majorities since the Second World War. purpose management Draghi then formed a government made up of different political forces, with the aim of tackling the consequences of the pandemic in a framework of national unity: in addition to various technical ministers (8), the 5 Star Movement (4), the Democratic Party (3), the Lega (3), Forza Italia (3), Liberi e Uguali (1) and Italia Viva (1) are represented in the Cabinet. This internal diversity, which on some issues manifests itself in opposing positions, could lead to some governmental instability.

Domestic politics: recovery and reforms

The Draghi government has made the vaccination campaign and economic recovery a priority, as well as reforms to the tax system and to public administration and the judiciary. The former ECB president has shown a certain capacity for both innovation in organisational Structures and the delegation of tasks, all of which will be tackled swiftly, according to his maxim that "we'll do it soon, we'll do it very soon".

Accelerating vaccination

As for the vaccination campaign, Draghi is applying maximisation and firmness. First of all, he reformed the administrative summits in charge of the vaccination plan and appointed General Francesco Paolo Figliuolo, a military logistician, as the new extraordinary commissioner for the Covid-19 emergency. By then, the daily doses provided reached 170,000, but Figliuolo, together with the director of the Civil Protection, Fabrizio Curcio, and the Minister of Health, Roberto Speranza, have set as goal to triple this number issue. To this end, new vaccination sites have been set up, such as businesses, gyms and empty car parks, and a mobilisation of staff has been promoted for vaccination work.

The Draghi government has also become more assertive at the international level, such as the decision to block the export of 250,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine to Australia. Although supported by the EU, the measure took many countries by surprise and made Italy the first EU member to apply such a legal mechanism. On 12 March the government announced the possibility of future production in Italy of some of the already internationally approved vaccines.

Economicsstructural reforms

The new government's economic diary will be characterised by structural reforms to promote productivity, as well as by the implementation of economic aid targeted at those most affected by the crisis, with the goal aim of relaunching the country and combating new social inequalities. The government is finalising the Recovery Plan to be submitted to Brussels in order to obtain the EU funds.

During his term as ECB President Draghi promoted structural reforms in several European countries; therefore, his leadership will be core topic in promoting reforms aimed at increasing productivity, reducing bureaucracy and improving the quality of Education. The government promises more expense on Education and the promotion of a more sustainable and digitised Economics , as called for by the EU Green Deal.

Through the "Sostegni" legislative decree, the government is implementing an aid plan. Some of them are aimed at defraying the modification of the framework redundancies implemented by Conte, but this requires a more consensual negotiation.

Streamlining of public administration and Justice

The reform of public administration has been entrusted to framework D'Alberti, lawyer and professor of Administrative Law at La Sapienza in Rome. The reform will follow two paths: greater connectivity and an update of the competences of civil servants.

In relation to Justice, the purpose is to implement several of the recommendations forwarded by the EU in 2019 and 2020. Among other measures, the EU calls for greater efficiency of the Italian civil justice system, through a faster work of courts, better burden-sharing work, the adoption of simpler procedural rules and an active crackdown on corruption.

Foreign policy: Atlanticism and less enthusiasm for China

One of the first consequences of Draghi's election as prime minister has been the new image of stability and willingness to cooperate that Italy has come to project not only in Brussels but also in Washington, both politically and economically. Nevertheless, many aspects of Conte's foreign policy will be maintained, given the continuity of Luigi di Maio as foreign minister.

Beyond Europe, Draghi's priorities will be mainly two: a new rapprochement with Washington - at framework of a convinced Atlanticism, within multilateralism - and the reinforcement of Italy's Mediterranean policy. Draghi's arrival also has the potential to break with Conte's rapprochement with China, such as the inclusion of Italian ports in the New Silk Road. While this may secure Italy as a key US ally, any decision will have to take into account the Chinese investment that may be committed.

Contribution to European governance

Italy is the third largest Economics in the EU and the eighth largest in the world, so its economic performance has some international repercussions. Draghi has assured his commitment to recovery and his contacts with European elites may help ease tensions in discussions with other EU members on the distribution of funds, especially the so-called Next Generation EU. During the Euro Crisis Draghi was one of the main advocates of structural reforms and now these are again vital to avoid a rise in expense that could cause debt to grow too high or cuts to budget that would damage growth.

Draghi has declared that "without Italy there is no Europe, but without Europe there is less Italy" and intends to make Italy a more active and engaged player in Europe, while trying to balance the interests of France, Germany and the Netherlands. Merkel's departure at the end of 2021 opens the possibility of a power vacuum in the European committee ; with France and Italy being the second and third Economics her partnership could bring stability and ensure the persistence of the Recovery Fund. This in turn may end up causing governance problems with Germany and the Netherlands should there be disagreements over the use of the funds. However, Draghi has been reticent about France's geopolitical proposals to establish Europe as an actor independent of the US. This could end up poisoning the potential new special relationship between Rome and Paris.

The advertisement willingness to engage in dialogue and concord with both Turkey and Russia may end up causing problems in Brussels with other countries. In Turkey's case, it could jeopardise relations with Greece in the Mediterranean. However, the strong criticism of Erdogan, whom he called a dictator, for having diplomatically humiliated Ursula von der Leyen in his visit to Ankara, seems to rule out counterproductive approaches. On the other hand, his desire for dialogue also with Moscow may end up sitting badly in the Baltic capitals, as well as in Washington.

The Mediterranean: immigration, Libya and Turkey

Draghi also referred to strategic areas outside the EU that are close to Italy: the Maghreb, the Middle East and the Mediterranean. Regarding the latter, Italy's priorities do not seem likely to change: the goal is to control immigration. To this end, Draghi hopes to establish cooperation with Spain, Greece and Cyprus.

In this area the stability of Libya is important, and Italian support for the Government of National agreement Government (GNA) established in Tripoli, one of whose main advocates in the EU has been Luigi Di Maio, who remains at the helm of Foreign Affairs, will continue. Libyan Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah has declared his readiness to collaborate on immigration issues with Draghi, but Draghi seems sceptical towards bilateral deals and would prefer this to be done at a European framework .

This runs counter to the policy of Greece and France, which support the Libyan National Army, based in Tubruk, because of the GNA's Islamist connections and Turkey's support for them. These differences over Libya have already caused problems and hindered the possibility of sanctions against Ankara.

Seizing the opportunity

The new Draghi government is an opportunity for Italy to achieve some political stability after a few years of ups and downs. The integration in the same government of people from different ideological backgrounds can contribute to the national unity required by the present status. The emergency and exceptional nature of the Covid-19 crisis gives Italy an opportunity to implement not only anti-pandemic measures but also radical structural changes to transform Economics and public administration, something that would otherwise be too much of a hindrance.

On the other hand, although within a certain continuity, Draghi's government represents a change in the international strategic chessboard, not only for Brussels, Berlin and Paris but also for Washington and Beijing, as more Atlanticist tendencies will distance him from both Russia and China.

Italian governments are not known for their longevity, nor does this one offer any guarantee of permanence, bearing in mind that the unity effort made is due to the temporary nature of the crisis. Nevertheless, Draghi's own profile projects an image of seriousness and responsibility.

Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelans and pending TPS termination for Central Americans amid a migration surge at the US-Mexico border

The Venezuelan flag near the US Capitol [Rep. Darren Soto].

ANALYSIS / Alexandria Angela Casarano

On March 8, the Biden administration approved Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for the cohort of 94,000 to 300,000+ Venezuelans already residing in the United States. Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti await the completion of litigation against the TPS terminations of the Trump administration. Meanwhile, the US-Mexico border faces surges in migration and detention facilities for unaccompanied minors battle overcrowding.

TPS and DED. The case of El Salvador

TPS was established by the Immigration Act of 1990 and was first granted to El Salvador that same year due to a then-ongoing civil war. TPS is a temporary immigration benefit that allows migrants to access education and obtain work authorization (EADs). TPS is granted to specific countries in response to humanitarian, environmental, or other crises for 6, 12, or 18-month periods-with the possibility of repeated extension-at the discretion of the Secretary of Homeland Security, taking into account the recommendations of the State Department.

The TPS designation of 1990 for El Salvador expired on June 30,1992. However, following the designation of Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) to El Salvador on June 26, 1992 by George W. Bush, Salvadorans were allowed to remain in the US until December 31, 1994. DED differs from TPS in that it is designated by the US President without the obligation of consultation with the State Department. Additionally, DED is a temporary protection from deportation, not a temporary immigration benefit, which means it does not afford recipients a legal immigration status, although DED also allows for work authorization and access to education.

When DED expired for El Salvador on December 31, 1994, Salvadorans previously protected by the program were granted a 16-month grace period which allowed them to continue working and residing in the US while they applied for other forms of legal immigration status, such as asylum, if they had not already done so.

The federal court system became significantly involved in the status of Salvadoran immigrants in the US beginning in 1985 with the American Baptist Churches v. Thornburgh (ABC) case. The ABC class action lawsuit was filed against the US Government by more than 240,000 immigrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and former Soviet Bloc countries, on the basis of alleged discriminatory treatment of their asylum claims. The ABC Settlement Agreement of January 31, 1991 created a 240,000-member immigrant group (ABC class members) with special legal status, including protection from deportation. Salvadorans protected under TPS and DED until December 31, 1994 were allowed to apply for ABC benefits up until February 16, 1996.

Venezuela and the 2020 Elections

The 1990's Salvadoran immigration saga bears considerable resemblance to the current migratory tribulations of many Latin American immigrants residing in the US today, as the expiration of TPS for four Latin American countries in 2019 and 2020 has resulted in the filing of three major lawsuits currently working their way through the US federal court system.

Approximately 5 million Venezuelans have left their home country since 2015 following the consolidation of Nicolás Maduro, on economic grounds and in pursuit of political asylum. Heavy sanctions placed on Venezuela by the Trump administration have exacerbated-and continue to exacerbate, as the sanctions have to date been left in place by the Biden administration-the severe economic crisis in Venezuela.

An estimated 238,000 Venezuelans are currently residing in Florida, 67,000 of whom were naturalized US citizens and 55,000 of whom were eligible to vote as of 2018. 70% of Venezuelan voters in Florida chose Trump over Biden in the 2020 presidential elections, and in spite of the Democrats' efforts (including the promise of TPS for Venezuelans) to regain the Latino vote of the crucial swing state, Trump won Florida's 29 electoral votes in the 2020 elections. The weight of the Venezuelan vote in Florida has thus made the humanitarian importance of TPS for Venezuela a political issue as well. The defeat in Florida has probably made President Biden more cautious about relieving the pressure on Venezuela's and Cuba's regimes.

The Venezuelan TPS Act was originally proposed to the US Congress on January 15, 2019, but the act failed. However, just before leaving office, Trump personally granted DED to Venezuela on January 19, 2021. Now, with the TPS designation to Venezuela by the Biden administration on March 8, Venezuelans now enjoy a temporary legal immigration status.

The other TPS. Termination and ongoing litigation

Other Latin American countries have not fared so well. At the beginning of 2019, TPS was designated to a total of four Latin American countries: Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti. Nicaragua and Honduras were first designated TPS on January 5, 1999 in response to Hurricane Mitch. El Salvador was redesignated TPS on March 9, 2001 after two earthquakes hit the country. Haiti was first designated TPS on January 21, 2010 after the Haiti earthquake. Since these designations, TPS was continuously renewed for all four countries. However, under the Trump administration, TPS was allowed to expire without renewal for each country, beginning with Nicaragua on January 5, 2019. Haiti followed on July 22, 2019, then El Salvador on September 9, 2019, and lastly Honduras on January 4, 2020.

As of March 2021, Salvadorans account for the largest share of current TPS holders by far, at a total of 247,697, although the newly eligible Venezuelans could potentially overshadow even this high figure. Honduras and Haiti have 79,415 and 55,338 TPS holders respectively, and Nicaragua has much fewer with only 4,421.

The elimination of TPS for Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti would result in the deportation of many immigrants who for a significant continuous period of time have contributed to the workforce, formed families, and rebuilt their lives in the United States. Birthright citizenship further complicates this reality: an estimated 270,000 US citizen children live in a home with one or more parents with TPS, and the elimination of TPS for these parents could result in the separation of families. Additionally, the conditions of Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti-in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, recent natural disasters (i.e. hurricanes Matthew, Eta, and Iota), and other socioeconomic and political issues-remain far from ideal and certainly unstable.

Three major lawsuits were filed against the US Government in response to the TPS terminations of 2019 and 2020: Saget v. Trump (March 2018), Ramos v. Nielsen (March 2018), and Bhattarai et al. v. Nielsen (February 2019). Kirstjen Nielsen served as Secretary of Homeland Security for two years (2017 - 2019) under Trump. Saget v. Trump concerns Haitian TPS holders. Ramos v. Nielsen concerns 250,000 Salvadoran, Nicaraguan, Haitain and Sudanese TPS holders, and has since been consolidated with Bhattarai et al. v. Nielsen which concerns Nepali and Honduran TPS holders.

All three (now two) lawsuits appeal the TPS eliminations for the countries involved on similar grounds, principally the racial animus (i.e. Trump's statement: "[Haitians] all have AIDS") and unlawful actions (i.e. violations of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA)) of the Trump administration. For Saget v. Trump, the US District Court (E.D. New York) blocked the termination of TPS (affecting Haiti only) on April 11, 2019 through the issuing of preliminary injunctions. For Ramos v. Nielson (consolidated with Bhattarai et al. v. Nielson), the US Court of Appeals of the 9th Circuit has rejected these claims and ruled in favour of the termination of TPS (affecting El Salvador, Nicaragua, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, and Sudan) on September 14, 2020. This ruling has since been appealed and is currently awaiting revision.

The US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have honored the orders of the US Courts not to terminate TPS until the litigation for these aforementioned cases is completed. The DHS issued a Federal Register Notice (FRN) on December 9, 2020 which extends TPS for holders from Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti until October 14, 2021. The USCIS has similarly cooperated and has ordered that so long as the litigation remains effective, no one will lose TPS. The USCIS has also ordered that in case of TPS elimination once the litigation is completed, Nicaragua and Haiti will have 120 grace days to orderly transition out of TPS, Honduras will have 180, and El Salvador will have 365 (time frames which are proportional to the number of TPS holders from each country, though less so for Haiti).

The Biden Administration's Migration Policy

On the campaign trail, Biden repeatedly emphasized his intentions to reverse the controversial immigration policies of the Trump administration, promising immediate cessation of the construction of the border wall, immediate designation of TPS to Venezuela, and the immediate sending of a bill to create a "clear [legal] roadmap to citizenship" for 11 million+ individuals currently residing in the US without legal immigration status. Biden assumed office on January 20, 2021, and issued an executive order that same day to end the government funding for the construction of the border wall. On February 18, 2021, Biden introduced the US Citizenship Act of 2021 to Congress to provide a legal path to citizenship for immigrants residing in the US illegally, and issued new executive guidelines to limit arrests and deportations by ICE strictly to non-citizen immigrants who have recently crossed the border illegally. Non-citizen immigrants already residing in the US for some time are now only to be arrested/deported by ICE if they pose a threat to public safety (defined by conviction of an aggravated felony (i.e. murder or rape) or of active criminal street gang participation).

Following the TPS designation to Venezuela on March 8, 2021, there has been additional talk of a TPS designation for Guatemala on the grounds of the recent hurricanes which have hit the country.

On March 18, 2021, the Dream and Promise Act passed in the House. With the new 2021 Democrat majority in the Senate, it seems likely that this legislation which has been in the making since 2001 will become a reality before the end of the year. The Dream and Promise Act will make permanent legal immigration status accessible (with certain requirements and restrictions) to individuals who arrived in the US before reaching the age of majority, which is expected to apply to millions of current holders of DACA and TPS.

If the US Citizenship Act of 2021 is passed by Congress as well, together these two acts would make the Biden administration's lofty promises to create a path to citizenship for immigrants residing illegally in the US a reality. Since March 18, 2021, the National TPS Alliance has been hosting an ongoing hunger strike in Washington, DC in order to press for the speedy passage of the acts.

The current migratory surge at the US-Mexico border

While the long-term immigration forecast appears increasingly more positive as Biden's presidency progresses, the immediate immigration situation at the US-Mexico border is quite dire. Between December 2020 and February 2021, the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported a 337% increase in the arrival of families, and an 89% increase in the arrival of unaccompanied minors. CBP apprehensions of migrants crossing the border illegally in March 2021 have reached 171,00, which is the highest monthly total since 2006.

Currently, there are an estimated 4,000 unaccompanied minors in CBP custody, and an additional 15,000 unaccompanied minors in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

The migratory CBP facility in Donna, TX designated specifically to unaccompanied minors has been filled at 440% to 900% of its COVID-19 capacity of just 500 minors since March 9, 2021. Intended to house children for no more than a 72-hour legal limit, due to the current overwhelmed system, some children have remained in the facility for more than weeks at a time before being transferred on to HHS.

In order to address the overcrowding, the Biden administration announced the opening of the Delphia Emergency Intake Site (next to the Donna facility) on April 6, 2021, which will be used to house up to 1,500 unaccompanied minors. Other new sites have been opened by HHS in Texas and California, and HHS has requested the Pentagon to allow it to temporarily utilize three military facilities in these same two states.

Political polarization has contributed to a great disparity in the interpretation of the recent surge in migration to the US border since Biden took office. Termed a "challenge" by Democrats and a "crisis" by Republicans, both parties offer very different explanations for the cause of the situation, each placing the blame on the other.

Following referendums in 2018 and 2019, the Guatemalan government submitted its report to The Hague in 2020 and the Belizean government has one year to reply.

Guatemala presented its position before the International Court of Justice in The Hague last December, with a half-year delay attributed to the Covid-19 emergency status ; Belize will now have a year to respond. Although the ICJ will then take its time to draft a judgement, it can be said that the territorial dispute between the two neighbours has entered its final stretch, bearing in mind that the dispute over this Central American enclave dates back to the 18th century.

Coats of arms of Guatemala (left) and Belize (right) on their respective flags.

article / Álvaro de Lecea

The territorial conflict between Guatemala and Belize has its roots in the struggle between the Spanish Empire in the Americas and British activity in the Caribbean during the colonial era. The Spanish Crown's inaction in the late 18th century in the face of British encroachment on what is now Belize, then Spanish territory, allowed the British to establish a foothold in Central America and begin exploiting mainland lands for precious woods such as dyewood and mahogany. However, Guatemala's reservations over part of the Belizean land - it claims over 11,000 square kilometres, almost half of the neighbouring country; it also claims the corresponding maritime extension and some cays - generated a status of tension and conflict that has continued to the present day.

In 2008, both countries decided to hold referendums on the possibility of taking the dispute to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which would rule on the division of sovereignty. The Belizeans approved taking that step in 2018 and the Guatemalans the following year. The issue was formalised before the ICJ in The Hague on 12 June 2019.

Historical context

The territory of present-day Belize was colonised by Spain in the mid-16th century as part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain and dependent on the captaincy of Guatemala. However, as there were no mineral resources there and hardly any population, the metropolis paid little attention to the area. This scant Spanish presence favoured pirate attacks, and to prevent them, the Spanish Crown allowed increasing English exploitation in exchange for defence. England carried out a similar penetration on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua, but while the Spanish managed to expel the English from there, they consolidated their settlement at area Belize and finally obtained the territory by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, whereby Spain disengaged itself from this corner of Central America. That concession and another three years later covered just 6,685 square kilometres, a space close to the coast that was later enlarged inland and southward by England, since Spain was not active in the area. From then on the enclave became known as "British Honduras".

The cession did not take into account the claims of the Guatemalans, who considered the space between the Sarstún and Sibún rivers to be their own. Both rivers run west-east, the former forming the border with Guatemala in the south of what is now Belize; the other, further north, runs through the centre of Belize, flowing into the capital, splitting the country in two. However, given the urgency for international recognition when it declared independence in 1821, Guatemala signed several agreements with England, the great power of the day, to ensure the viability of the new state. One of these was the Aycinena-Wyke Treaty (1859), whereby Guatemala accepted Belize's borders in exchange for the construction of a road to improve access from its capital to the Caribbean. However, both sides blamed the other for not complying with the treaty (the road was not built, for example) and Guatemala declared it null and void in 1939.

In the constitution enacted in 1946, Guatemala included the claim in the drafting, and has insisted on this position since the neighbouring country, under the name Belize, gained its independence from the United Kingdom in 1981. As early as 1978, the UN passed a resolution guaranteeing the rights to self-determination and territorial protection of the Belizean people, which also called for a peaceful resolution of the neighbouring conflict. Guatemala did not recognise the existence of the new sovereign state until 1991, and even today still places some limits on Belize's progressive integration into the Central American Integration System. Because of its English background, Belize has historically maintained a closer relationship with the English-speaking Caribbean islands.

Map of Central America and, in detail, the territorial dispute between Guatemala and Belize [Rei-artur / Janitoalevic Bettyreategui].

Adjacency Line and the role of the OAS

Since 2000, the Organisation of American States (OAS), of which both nations are members, has been mediating between the two countries. In the same year, the OAS facilitated a agreement with the goal aim of building confidence and negotiations between the two neighbours. In order to achieve these objectives, the OAS, through its Peace Fund, actively supported the search for a solution by providing technical and political support. Indeed, as a result of this rapprochement, talks on the dispute were resumed and the creation of the "Adjacency Line" was agreed.

This is an imaginary line that basically follows the line that "de facto" separated the two countries from north to south and is where most of the tensions are taking place. Over the years, both sides have increased their military presence there, in response to incidents attributed to the other side. Due to these frequent disputes, in 2015 Belize had to request financial aid military presence from the British navy. It is precisely in the Adjacency Zone that an OAS office is located, whose purpose purpose is to promote contacts between the communities and to verify certain transgressions of the agreements already signed.

One of the most promising developments that took place under the umbrella of the OAS was the signature in 2008 of what was called the "specialagreement between Guatemala and Belize to submit Guatemala's territorial, insular and maritime claim to the International Court of Justice". Under this agreement both countries undertook to submit the acceptance of the Court's mediation to simultaneous popular consultations. However, in 2015, through the protocol of the agreement Special between Belize and Guatemala, these popular consultations were not allowed to take place at the same time. Both parties committed to accept the Court's decision as "decisive and binding" and to comply with and implement it "fully and in good faith".

The Hague and the impact of the future resolution

The referendums were held in 2018 in the case of Guatemala and in 2019 in the case of Belize. Although the percentages of both popular consultations were somewhat mixed, the results were positive. In Belize, the Yes vote won 55.37% of the votes and the No vote 44.63%. In Guatemala, on the other hand, the results were much more favourable for the Yes vote, with 95.88% of the votes, compared to 4.12% for the No vote.

These results show how the Belizeans are wary of resorting to the Hague's decision because, although by fixing final the border they will forever close any claim, they risk losing part of their territory. On the other hand, the prospect of gain is greater in the Guatemalan case, since if its proposal is accepted - or at least part of it - it would strategically expand its access to the Caribbean, now somewhat limited, and in the event of losing, it would simply remain as it has been until now, which is not a serious problem for the country.

The definition of a clear and respected border is necessary at this stage. The adjacent line, observed by the OAS peace and security mission statement , has been successful in limiting tensions between the two countries, but the reality is that certain incidents continue to take place in this unprotected area. These incidents, such as the assassination of citizens of both countries or mistreatment attributed to the Guatemalan military, cause the conflict to drag on and tensions to rise. On the other hand, the lack of a clear definition of borders facilitates drug trafficking and smuggling.

This conflict has also affected Belize's economic and trade relations with its regional neighbours, especially Mexico and Honduras. This is not only due to the lack of land boundaries, but also to the lack of maritime boundaries. This area is very rich in natural resources and has the second largest coral reef reservation in the world, after Australia. This has, unsurprisingly, affected bilateral relations between the two countries. Whilst regional organisations are calling for greater regional integration, the tensions between Belize and Guatemala are preventing any improvement in this regard.

The Guatemalan president has stated that, regardless of the Court's result , he intends to strengthen bilateral relations, especially in areas such as trade and tourism, with neighbouring Belize. For their part, the Caricom heads of state expressed their support for Belize in October 2020, their enthusiasm for the ICJ's intervention and their congratulations to the OAS for its mediation work.

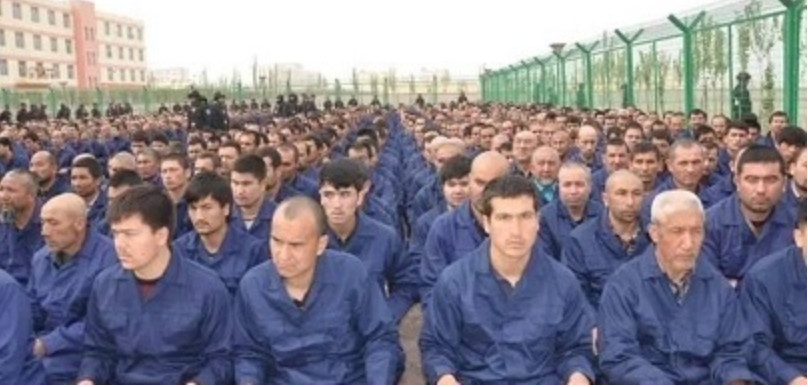

Detainee in a Xinjiang re-education camp located in Lop County listening to "de-radicalization" talks [Baidu baijiahao].

Detainee in a Xinjiang re-education camp located in Lop County listening to "de-radicalization" talks [Baidu baijiahao].

ESSAY / Rut Noboa

Over the last few years, reports of human rights violations against Uyghur Muslims, such as extrajudicial detentions, torture, and forced labor, have been increasingly reported in the Xinjiang province's so-called "re-education" camps. However, the implications of the Chinese undertakings on the province's ethnic minority are not only humanitarian, having direct links to China's ongoing economic projects, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and natural resource extraction in the region. Asides from China's economic diary, ongoing projects in Xinjiang appear to prototype future Chinese initiatives in terms of expanding the surveillance state, particularly within the scope of technology. When it comes to other international actors, the Xinjiang dispute has evidenced a growing diplomatic split between countries against it, mostly western liberal democracies, and countries willing to at least defend it, mostly countries with important ties to China and dubious human rights records. The issue also has important repercussions for multinational companies, with supply chains of well-known international companies such as Nike and Apple benefitting from forced Uyghur labour. The situation in Xinjiang is critically worrisome when it comes to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly considering recent outbreaks in Kashgar, how highly congested these "reeducation" camps, and potential censorship from the government. Finally, Uyghur communities continue to be an important factor within this conversation, not only as victims of China's policies but also as dissidents shaping international opinion around the matter.

The Belt and Road Initiative

Firstly, understanding Xinjiang's role in China's ongoing projects requires a strong geographical perspective. The northwestern province borders Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India, giving it important contact with other regional players.

This also places it at the very heart of the BRI. With it setting up the twenty-first century "Silk Road" and connecting all of Eurasia, both politically and economically, with China, it is no surprise that it has managed to establish itself as China's biggest infrastructural project and quite possibly the most important undertaking in Chinese policy today. Through more and more ambitious efforts, China has established novel and expansive connections throughout its newfound spheres of influence. From negotiations with Pakistan and the establishment of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) securing one of the most important routes in the initiative to Sri Lanka defaulting on its loan and giving China control over the Hambantota Port, the Chinese government has managed to establish consistent access to major trade routes.

However, one important issue remains: controlling its access to Central Asia. One of the BRI's initiative's key logistical hubs is Xinjiang, where the Uyghurs pose an important challenge to the Chinese government. The Uyghur community's attachment to its traditional lands and culture is an important risk to the effective implementation of the BRI in Xinjiang. This perception is exacerbated by existing insurrectionist groups such as the East Turkestan independence movement and previous events in Chinese history, including the existence of an independent Uyghur state in the early 20th century[1]. Chinese infrastructure projects that cross through the Xinjiang province, such as the Central Asian High-speed Rail are a priority that cannot be threatened by instability in the region, inspiring the recent "reeducation" and "de-extremification" policies.

Natural resource exploitation

Another factor for China's growing control over the region is the fact that Xinjiang is its most important energy-producing region, even reaching the point where key pipeline projects connect the northwestern province with China's key coastal cities and approximately 60% of the province's gross regional production comes from oil and natural gas extraction and related industries[2]. With China's energy consumption being on a constant rise[3] as a result of its growing economy, control over Xinjiang is key to Chinese.

Additionally, even though oil and natural gas are the region's main industries, the Chinese government has also heavily promoted the industrial-scale production of cotton, serving as an important connection with multinational textile-based corporations seeking cheap labour for their products.

This issue not only serves as an important reason for China to control the Uyghurs but also promotes instability in the region. The increased immigration from a largely Han Chinese workforce, perceived unequal distribution of revenue to Han-dominated firms, and increased environmental costs of resource exploitation have exacerbated the pre-existing ethnic conflict.

A growing diplomatic split

The situation in Xinjiang also has important implications for international perceptions of Chinese propaganda. China's actions have received noticeable backlash from several states, with 22 states issuing a joint statement to the Human Rights Council on the treatment of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang on July 8, 2019. These states called upon China "to uphold its national laws and international obligations and to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms".

Meanwhile, on July 12, 2019, 50 (originally 37) other states issued a competing letter to the same institution, commending "China's remarkable achievements in the field of human rights", stating that people in Xinjiang "enjoy a stronger sense of happiness, fulfillment and security".

This diplomatic split represents an important and growing division in world politics. When we look at the signatories of the initial letter, it is clear to see that all are developed democracies and most (except for Japan) are Western. Meanwhile, those countries that chose to align themselves with China represent a much more heterogeneous group with states from the Middle East, Asia, and Africa[4]. Many of these have questionable human rights records and/or receive important funding and investment from the Chinese government, reflecting both the creation of an alternative bloc distanced from Western political influence as well as an erosion of preexisting human rights standards.

China's Muslim-majority allies: A Pakistani case study

The diplomatic consequences of the Xinjiang controversy are not only limited to this growing split, also affecting the political rhetoric of individual countries. In the last years, Pakistan has grown to become one of China's most important allies, particularly within the context of CPEC being quite possibly one of the most important components of the BRI.

As a Muslim-majority country, Pakistan has traditionally placed pan-Islamic causes, such as the situations in Palestine and Kashmir, at the centre of its foreign policy. However, Pakistan's position on Xinjiang appears not just subdued but even complicit, never openly criticising the situation and even being part of the mentioned letter in support of the Chinese government (alongside other Muslim-majority states such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE). With Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan addressing the General Assembly in September 2019 on Islamophobia in post-9/11 Western countries as well as in Kashmir but conveniently omitting Uyghurs in Xinjiang[5], Pakistani international rhetoric weakens itself constantly. Due to relying on China for political and economic support, it appears that Pakistan will have to censor itself on these issues, something that also rings true for many other Muslim-majority countries.

Central Asia: complacent and supportive

Another interesting case study within this diplomatic split is the position of different countries in the Central Asian region. These states - Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan - have the closest cultural ties to the Uyghur population. However, their foreign policy hasn't been particularly supportive of this ethnic group with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan avoiding the spotlight and not participating in the UNHRC dispute and Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan being signatories of the second letter, explicitly supporting China. These two postures can be analyzed through the examples of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Kazakhstan has taken a mostly ambiguous position to the situation. Having the largest Uyghur population outside China and considering Kazakhs also face important persecution from Chinese policies that discriminate against minority ethnic groups in favour of Han Chinese citizens, Kazakhstan is quite possibly one of the states most affected by the situation in Xinjiang. However, in the last decades, Kazakhstan has become increasingly economically and, thus, politically dependent on China. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan implemented what some would refer to as a "multi-vector" approach, seeking to balance its economic engagements with different actors such as Russia, the United States, European countries, and China. However, with American and European interests in Kazakhstan decreasing over time and China developing more and more ambitious foreign policy within the framework of strategies such as the Belt and Road Initiative, the Central Asian state has become intimately tied to China, leading to its deafening silence on Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

A different argument could be made for Uzbekistan. Even though there is no official statistical data on the Uyghur population living in Uzbekistan and former president Islam Karimov openly stated that no Uyghurs were living there, this is highly questionable due to the existing government censorship in the country. Also, the role of Uyghurs in Uzbekistan is difficult to determine due to a strong process of cultural and political assimilation, particularly in the post-Soviet Uzbekistan. By signing the letter to the UNHCR in favour of China's practices, the country has chosen a more robust support of its policies.

All in all, the countries in Central Asia appear to have chosen to tolerate and even support Chinese policies, sacrificing cultural values for political and economic stability.

Forced labour, the role of companies, and growing backlash

In what appears to be a second stage in China's "de-extremification" policies, government officials have claimed that the "trainees "in its facilities have "graduated", being transferred to factories outside of the province. China claims these labor transfers (which it refers to as vocational training) to be part of its "Xinjiang Aid" central policy[6]. Nevertheless, human rights groups and researchers have become growingly concerned over their labor standards, particularly considering statements from Uyghur workers who have left China describing the close surveillance from personnel and constant fear of being sent back to detention camps.

Within this context, numerous companies (both Chinese and foreign) with supply chain connections with factories linked to forced Uyghur labour have become entangled in growing international controversies, ranging from sportswear producers like Nike, Adidas, Puma, and Fila to fashion brands like H&M, Zara, and Tommy Hilfiger to even tech players such as Apple, Sony, Samsung, and Xiaomi[7]. Choosing whether to terminate relationships with these factories is a complex choice for these companies, having to either lose important components of their intricate supply chains or face growing backlash on an increasingly controversial issue.

The allegations have been taken seriously by these groups with organizations such as the Human Rights Watch calling upon concerned governments to take action within the international stage, specifically through the United Nations Human Rights Council and by imposing targeted sanctions at responsible senior officials. Another important voice is the Coalition to End Forced Labour in the Uyghur Region, a coalition of civil society organizations and trade unions such as the Human Rights Watch, the Investor Alliance for Human Rights, the World Uyghur Congress, and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, pressuring the brands and retailers involved to exclude Xinjiang from all components of the supply chain, especially when it comes to textiles, yarn or cotton as well as calling upon governments to adopt legislation that requires human rights due diligence in supply chains. Additionally, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, the same organisation that carried out the initial report on forced Uyghur labor and surveillance beyond Xinjiang and within the context of these labor transfers, recently created the Xinjiang Data Project. This initiative documents ongoing Chinese policies on the Uyghur community with open-source data such as satellite imaging and official statistics and could be decidedly useful for human rights defenders and researchers focused on the topic.

One important issue when it comes to the labour conditions faced by Uyghurs in China comes from the failures of the auditing and certification industry. To respond to the concerns faced by having Xinjiang-based suppliers, many companies have turned to auditors. However, with at least five international auditors publicly stating that they would not carry out labor-audit or inspection services in the province due to the difficulty of working with the high levels of government censorship and monitoring, multinational companies have found it difficult to address these issues[8]. Additionally, we must consider that auditing firms could be inspecting factories that in other contexts are their clients, adding to the industry's criticism. These complaints have led human rights groups to argue that overarching reform will be crucial for the social auditing industry to effectively address issues such as excessive working hours, unsafe labor conditions, physical abuse, and more[9].

Xinjiang: a prototype for the surveillance state

From QR codes to the collection of biometric data, Xinjiang has rapidly become the lab rat for China's surveillance state, especially when it comes to technology's role in the issue.

One interesting area being massively affected by this is travel. As of September 2016, passport applicants in Xinjiang are required to submit a DNA sample, a voice recording, a 3D image of themselves, and their fingerprints, much harsher requirements than citizens in other regions. Later in 2016, Public Security Bureaus across Xinjiang issued a massive recall of passports for an "annual review" followed by police "safekeeping"[10].

Another example of how a technologically aided surveillance state is developing in Xinjiang is the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), a big data program for policing that selects individuals for possible detention based on specific criteria. According to the Human Rights Watch, which analyzed two leaked lists of detainees and first reported on the policing program in early 2018, the majority of people identified by the program are being persecuted because of lawful activities, such as reciting the Quran and travelling to "sensitive" countries such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Additionally, some criteria for detention appear to be intentionally vague, including "being generally untrustworthy" and "having complex social ties"[11].

Xinjiang's case is particularly relevant when it comes to other Chinese initiatives, such as the Social Credit System, with initial measures in Xinjiang potentially aiding to finetune the details of an evolving surveillance state in the rest of China.

Uyghur internment camps and COVID-19

The implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Uyghurs in Xinjiang are pressing issues, particularly due to the virus's rapid spread in highly congested areas such as these "reeducation" camps.

Currently, Kashgar, one of Xinjiang's prefectures is facing China's most recent coronavirus outbreak[12]. Information from the Chinese government points towards a limited outbreak that is being efficiently controlled by state authorities. However, the authenticity of this data is highly controversial within the context of China's early handling of the pandemic and reliance on government censorship.

Additionally, the pandemic has more consequences for Uyghurs than the virus itself. As the pandemic gives governments further leeway to limit rights such as the right to assembly, right to protest, and freedom of movement, the Chinese government gains increased lines of action in Xinjiang.

Uyghur communities abroad

The situation for Uyghurs living abroad is far from simple. Police harassment of Uyghur immigrants is quite common, particularly through the manipulation and coercion of their family members still living in China. These threatening messages requesting staff information or pressuring dissidents abroad to remain silent. The officials rarely identify themselves and in some cases these calls or messages don't necessarily even come from government authorities, instead coming from coerced family members and friends[13]. One interesting case was reported in August 2018 by US news publication The Daily Beast in which an unidentified Uyghur American woman was asked by her mother to send over pictures of her US license plate number, her phone number, her bank account number, and her ID card under the excuse that China was creating a new ID system for all Chinese citizens, even those living abroad[14]. A similar situation was reported by Foreign Policy when it came to Uyghurs in France who have been asked to send over home, school, and work addresses, French or Chinese IDs, and marriage certificates if they were married in France[15].

Regardless of Chinese efforts to censor Uyghur dissidents abroad, their nonconformity has only grown with the strengthening of Uyghur repression in mainland China. Important international human rights groups such as Amnesty International and the Human Rights Watch have been constantly addressing the crisis while autonomous Uyghur human rights groups, such as the Uyghur Human Rights Project, the Uyghur American Association, and the Uyghur World Congress, have developed from communities overseas. Asides from heavily protesting policies such as the internment camps and increasing surveillance in Xinjiang, these groups have had an important role when it comes to documenting the experiences of Uyghur immigrants. However, reports from both human rights group and average agencies when it comes to the crisis have been met with staunch rejection from China. One such case is the BBC being banned in China after recently reporting on Xinjiang internment camps, leading it to be accused of not being "factual and fair" by the China National Radio and Television Administration. The UK's Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab referred to the actions taken by the state authorities as "an unacceptable curtailing of average freedom" and stated that they would only continue to damage China's international reputation[16].

One should also think prospectively when it comes to Uyghur communities abroad. As seen in the diplomatic split between countries against China's policies in Xinjiang and those who support them (or, at the very least, are willing to tolerate them for their political interest), a growing number of countries can excuse China's treatment of Uyghur communities. This could eventually lead to countries permitting or perhaps even facilitating China's attempts at coercing Uyghur immigrants, an important prospect when it comes to countries within the BRI and especially those with an important Uyghur population, such as the previously mentioned example of Kazakhstan.

REFERENCES

[1] Qian, Jingyuan. 2019. "Ethnic Conflicts and the Rise of Anti-Muslim Sentiment in Modern China." Department of Political Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3450176.

[2] Cao, Xun, Haiyan Duan, Chuyu Liu, James A. Piazza, and Yingjie Wei. 2018. "Digging the "Ethnic Violence in China" Database: The Effects of Inter-Ethnic Inequality and Natural Resources Exploitation in Xinjiang." The China Review (The Chinese University of Hong Kong) 18 (No. 2 SPECIAL THEMED SECTION: Frontiers and Ethnic Groups in China): 121-154. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26435650

[3] International Energy Agency. 2020. Data & Statistics - IEA. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics?country=CHINA&fuel=Energy%20consumption&indicator=TotElecCons.

[4] Yellinek, Roie, and Elizabeth Chen. 2019. "The "22 vs. 50" Diplomatic Split Between the West and China." China Brief (The Jamestown Foundation) 19 (No. 22): 20-25. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://jamestown.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Read-the-12-31-2019-CB-Issue-in-PDF.pdf?x91188.

[5] United Nations General Assembly. 2019. "General Assembly official records, 74th session : 9th plenary meeting." New York. Accessed October 18, 2020.

[6] Xu, Vicky Xiuzhong, Danielle Cave, James Leibold, Kelsey Munro, and Nathan Ruser. 2020. "Uyghurs for sale: 'Re-education', forced labour and surveillance beyond Xinjiang." Policy Brief, International Cyber Policy Centre, Australian Strategic Policy Paper. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/uyghurs-sale

[7] Ibid.

[8] Xiao, Eva. 2020. Auditors to Stop Inspecting Factories in China's Xinjiang Despite Forced-Labor Concerns. 21 September. Accessed December 2020, 16. https://www.wsj.com/articles/auditors-say-they-no-longer-will-inspect-labor-conditions-at-xinjiang-factories-11600697706.

[9] Kashyap, Aruna. 2020. Social Audit Reforms and the Labor Rights Ruse. 7 October. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/07/social-audit-reforms-and-labor-rights-ruse.

[10] Human Rights Watch. 2016. China: Passports Arbitrarily Recalled in Xinjiang. 21 November. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/11/22/china-passports-arbitrarily-recalled-xinjiang

[11] Human Rights Watch. 2020. China: Big Data Program Targets Xinjiang's Muslims. 9 December. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/09/china-big-data-program-targets-xinjiangs-muslims.

[12] National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. 2020. How China's Xinjiang is tackling new COVID-19 outbreak. 29 October. Accessed November 14, 2020. http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2020-10/29/c_81994.htm.

[13] Uyghur Human Rights Project. 2019. "Repression Across Borders: The CCP's Illegal Harassment and Coercion of Uyghur Americans."

[14] Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany. 2018. Chinese Cops Now Spying on American Soil. 14 August. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://www.thedailybeast.com/chinese-police-are-spying-on-uighurson-american-soil.

[15] Allen-Ebrahimian. 2018. Chinese Police Are Demanding staff Information From Uighurs in France. 2 March. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/03/02/chinese-police-are-secretly-demanding-staff-information-from-french-citizens-uighurs-xinjiang/.

[16] Reuters Staff. 2021. BBC World News barred in mainland China, radio dropped by HK public broadcaster. 11 February. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-britain-bbc/bbc-world-news-barred-from-airing-in-china-idUSKBN2AB214.

Qatar's economic strengthening and expanding relations with Russia, China and Turkey have made the blockade imposed by its Gulf neighbours less effective.

It is a reality: Qatar has won its battle against the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia after more than three years of diplomatic rupture in which both countries, along with other Arab neighbours, isolated the Qatari peninsula commercially and territorially. Economic and geopolitical reasons explain why the imposed blockade has finally faded without Qatar giving in to its autonomous diplomatic line.

Qatar's Emir Tamim Al Thani at lecture Munich Security 2018 [Kuhlmann/MSC].

article / Sebastián Bruzzone

In June 2017, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Libya, Yemen and the Maldives accused the Al Thani family of supporting Islamic terrorism and the Muslim Brotherhood and initiated a total blockade on trade to and from Qatar until Doha met thirteen conditions. On 5 January 2021, however, Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman welcomed Qatar's Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani with an unexpected embrace in the Saudi city of Al-Ula, sealing the end of yet another dark chapter in the modern history of the Persian Gulf. But how many of the thirteen demands has Qatar met to reconcile with its neighbours? None.

As if nothing had happened. Tamim Al Thani arrived in Saudi Arabia to participate in the 41st Summit of the committee Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) where member states pledged to make efforts to promote solidarity, stability and multilateralism in the face of the challenges in the region, which is confronted by Iran's nuclear and ballistic missile programme, as well as its plans for sabotage and destruction. In addition, the GCC as a whole welcomed the mediating role of Kuwait, then US President Donald J. Trump and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner.

The Gulf Arab leaders' meeting has been a thaw in the political desert after a storm of mutual accusations and instability in what was called the "Qatar diplomatic crisis"; this rapprochement, as an immediate effect, clears the way for the normal preparation of the football World Cup scheduled to take place in Qatar next year. The return of regional and diplomatic understanding is always positive in emergency situations such as an economic crisis, a global pandemic or a common Shia enemy arming missiles on the other side of the sea. In any case, the Al Thani's Qatar may be crowned as the winner of the economic pulse against the Emirati Al Nahyan and the Saudi Al Saud unable to suffocate the tiny peninsula.

The factors

The relevant question brings us back to the initial degree scroll before these lines: how has Qatar managed to withstand the pressure without buckling at all in the face of the thirteen conditions demanded in 2017? Several factors contribute to explaining this.

First, the capital injection by the QIA (Qatar Investment Authority). At the beginning of the blockade, the banking system suffered a capital flight of more than 30 billion dollars and foreign investment fell sharply. The Qatari sovereign wealth fund responded by pumping in $38.5 billion to provide liquidity to banks and revive Economics. The sudden trade blockade by the UAE and Saudi Arabia led to a financial panic that prompted foreign investors, and even Qatari residents, to transfer their assets out of the country and liquidate their positions in fear of a market collapse.

Second, rapprochement with Turkey. In 2018, Qatar came to Turkey's rescue by pledging to invest $15 billion in Turkish assets across subject and, in 2020, to execute a currency swap agreement to raise the value of the Turkish lira. In reciprocity, Turkey increased commodity exports to Qatar by 29 per cent and increased its military presence in the Qatari peninsula against a possible invasion or attack by its neighbours, building a second Turkish military base near Doha. In addition, as an internal reinforcement measure, the Qatari government has invested more than $30 billion in military equipment, artillery, submarines and aircraft from American companies.

Third, rapprochement with Iran. Qatar shares with the Persian country the South Pars North Dome gas field, considered the largest in the world, and positioned itself as a mediator between the Trump administration and the Ayatollah government. Since 2017, Iran has supplied 100,000 tonnes of food daily to Doha in the face of a potential food crisis caused by the blockade of the only land border with Saudi Arabia through which 40 per cent of the food enters.

Fourth, rapprochement with Russia and China. The Qatari sovereign wealth fund acquired a 19% stake in Rosneft, opening the door to partnership between the Russian oil company and Qatar Petroleum and to more joint ventures between the two nations. In the same vein, Qatar Airways increased its stake in China Southern Airlines to 5%.

Fifth, its reinforcement as the world's leading exporter of LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas). It is important to know that Qatar's main economic engine is gas, not oil. That is why, in 2020, the Qatari government launched its expansion plan by approving a $50 billion investment to expand its liquefaction and LNG carrier capacity, and a $29 billion investment to build more offshore offshore platforms at North Dome. The Qatari government has forecast that its LNG production will grow by 40% by 2027, from 77 million tonnes to 110 million tonnes per year.

We should bear in mind that LNG transport is much safer, cleaner, greener and cheaper than oil transport. Moreover, Royal Dutch Shell predicted in its report "Annual LNG Outlook Report 2019" that global LNG demand would double by 2040. If this forecast is confirmed, Qatar would be on the threshold of impressive economic growth in the coming decades. It is therefore in its best interest to keep its public coffers solvent and maintain a stable political climate in the Middle East region at status . As if that were not enough, last November 2020, Tamim Al Thani announced that future state budgets will be configured on the basis of a fictitious price of $40 per barrel, a much smaller value than the WTI Oil Barrel or Brent Oil Barrel, which is around $60-70. In other words, the Qatari government will index its public expense to the volatility of hydrocarbon prices. In other words, Qatar is seeking to anticipate a possible collapse in the price of crude oil by promoting an efficient public expense policy.

And sixth, the maintenance of the Qatar Investment Authority's investment portfolio , valued at $300 billion. The assets of the Qatari sovereign wealth fund constitute a life insurance policy for the country, which can order its liquidation in situations of extreme need.

Qatar has a very important role to play in the future of the Persian Gulf. The Al Thani dynasty has demonstrated its capacity for political and economic management and, above all, its great foresight for the future vis-à-vis the other countries of the Gulf Cooperation committee . The small peninsular "pearl" has struck a blow against Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Abu Dhabi's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, who did not even show up in Al-Ula. This geopolitical move, plus the Biden administration's decision to maintain a hardline policy towards Iran, seems to guarantee the international isolation of the Ayatollah regime from the Persian country.

Several countries in the Americas are celebrating in 2021 their two hundredth anniversary of a break with Spain that did not always mean independence.ca celebrate in 2021 their two centuries of a break with Spain that did not always mean independence. final

This year, several American nations are commemorating two centuries of their separation from Spain, recalling a process that took place in all the Spanish possessions in continental America within a few years of each other. In some cases, it was a process of successive independence, as was the case with Guatemala, which later belonged to the Mexican Empire and then to a Central American republic, and Panama, which was part of Colombia until the 20th century. But even later, both countries experienced direct interference by the United States, in episodes that were very decisive for the region as a whole.

Ceremony of submission of the Panama Canal to the Panamanian authorities, 31 December 1999

article / Angie Grijalva

During 2021 several American countries celebrate their independence from Spain, the largest and most festively celebrated being Mexico. In other nations, the date of 1821 is qualified by later historical developments: Panama also commemorates every year the day in 1903 when it broke with Bogotá, while in the case of Guatemala that independence did not immediately imply a republic of its own, since together with its neighbouring nations in 1822 it was nominally dependent on Mexico and between 1823 and 1839 it formed part of the United Provinces of Central America and the Federal Republic of Central America. Moreover, US regional hegemony called into question the full sovereignty of these countries in subsequent decades: Guatemala suffered the first coup d'état openly promoted by Washington in the Western Hemisphere in 1954, and Panama did not have full control over its entire territory until the Americans handed over the canal in 1999.

Panama and its canal

The project of the Panama Canal was important for the United States because it made it possible to easily link its two coasts by sea and consolidated the global rise sought by Theodore Roosevelt's presidency, guided by the maxim that only the nation that controlled both oceans would be a truly international power. Given the refusal of Colombia, to which the province of Panama then belonged, to accept the conditions set by the United States to build the canal, resuming the work on the paralysed French project , Washington was faced with two options: invade the isthmus or promote Panama's independence from Colombia[1]. The Republic of Panama declared its independence on 3 November 1903 and with it Roosevelt negotiated a very favourable agreement which gave the United States perpetual sovereignty over the canal and a wide strip of land on either side of it. Washington thus gained control of Panama and extended its regional dominance.

After a decade of difficult work and a high issue death toll among the workforce, who came from all over the Caribbean and also from Asia, not least due to dengue fever, malaria and yellow fever, in 1913 the Atlantic and Pacific oceans were finally connected and the canal was opened to ship traffic.

Over time, US sovereignty over a portion of the country and the instructions military installations there fuelled a rejection movement in Panama that became particularly virulent in the 1960s. The Carter Administration agreed to negotiate the cession of the canal in a 1977 agreement that incorporated the Panamanians into the management of inter-oceanic traffic and set the submission of all installations for 1999. When this finally happened, the country experienced the occasion as a new independence celebration, saying goodbye to US troops that only ten years earlier had been very active, invading Panama City and other areas to arrest President Manuel Noriega for drug trafficking.

Critical moment in Guatemala

The Panama Canal gave the United States an undoubted projection of power over its hemisphere. However, during the Cold War, Washington also found it necessary to use operations, in some cases direct, to overthrow governments it considered close to communism. This happened with the overthrow of Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala in 1954.

The arrival of Árbenz to the presidency in 1951 was a threat to the United Fruit Company (UFCO) because of the agrarian reform he was promoting[2]. Although the advance of communist parties in Latin America was beginning to grow, the real threat in certain countries was the expropriation of land from US monopolies. It is estimated that by 1950, the UFCO owned at least 225,000 hectares of land in Guatemala, of which the agrarian reform was to expropriate 162,000 hectares in 1952. With political support from Washington, UFCO claimed that the compensation it was being offered did not correspond to the true value of the land and branded the Árbenz government as communist, even though this was not true.

In 1953, the newly inaugurated Eisenhower Administration established a plan to destabilise the government and stage a coup against Árbenz. On the one hand, Secretary of State John F. Dulles sought the support of the Organisation of American States, prompting condemnation of Guatemala for receiving a shipment of arms from the Soviet Union, which had been acquired because of the US refusal to sell arms to the Central American country. On the other hand, the CIA launched the mission statement PBSUCCESS to guarantee the quartermastering of a faction of the Guatemalan army ready to rebel against Árbenz. The movement was led by Colonel Castillo Armas, who was in exile in Honduras and from there launched the invasion on 18 June 1954. When the capital was bombed, the bulk of the army refused to respond, leaving Árbenz alone, who resigned within days.

Once in power, Castillo Armas returned the expropriated land to UFCO and brought new US investors into the country. Dulles called this victory "the greatest triumph against communism in the last five years". The overthrow of Árbenz was seen by the US as a model for further operations in Latin America. development The award Nobel Literature Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa has pointed out that this action against Árbenz could be seen as "the moment when Latin America was screwed", as for many it was evidence that a normal democracy was not possible, and this pushed certain sectors to defend revolution as the only way to make their societies prosper.

[1] McCullough, D. (2001). The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914. Simon & Schuster.

[2] G. Rabe, S. (2017). Intervention in Guatemala, 1953-1954. In S. G. Rabe, Eisenhower and Latin America: The Foreign Policy of Anticommunism. The University of North Carolina Press.