Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Energy, resources and sustainability .

The country left the cartel in order to expand pumping, but the Covid-19 crisis has cut extraction volumes by 10.8%.

Construction of a variant of the oil pipeline that crosses the Andes, from the Ecuadorian Amazon to the Pacific [Petroecuador].

ANALYSIS / Jack Acrich and Alejandro Haro

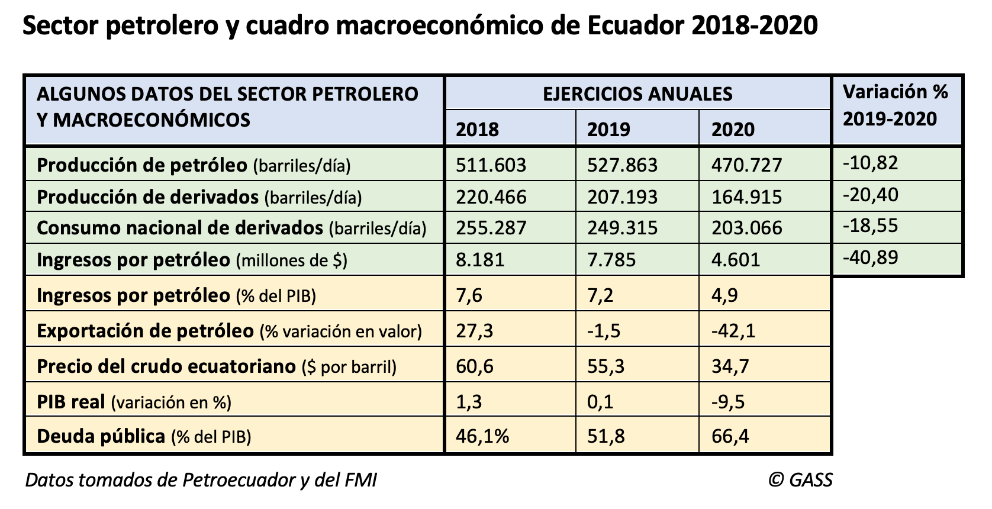

Ecuador left the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) on 1 January 2020 to avoid having to continue to join the production cuts imposed by group , which it agrees to in order to push up the world price of crude oil. Ecuador preferred to sell more barrels, albeit at a lower price, because by exporting more at the end of the day written request it could increase its income and thus get out of its serious financial situation status , which the coronavirus emergency has only accentuated, with a fall in GDP in 2020 currently estimated at 9.5 per cent.

However, domestic economic difficulties and the difficult international situation have not only prevented Ecuador from expanding pumping, but oil production has fallen by 10.8% in the last year. average In 2020, Ecuador extracted 472,000 barrels of oil per day, especially affected by the sharp reduction in activity in April with the beginning of the confinement, which was not compensated for the rest of the year. agreement This is a volume that is below the 500,000 line that has always been exceeded in recent years (in 2019 production was 528,000), according to figures from Petroecuador, the state hydrocarbons company. The reduction in global consumption during the Covid-19 year also correlated with a drop in the consumption of derivatives in Ecuador, especially gasoline and diesel, which fell by 18.5%.

International investment constrained by the pandemic context and reduced consumption marked a status that could hardly lead to an increase in production. In 2020, Ecuador saw a drop in the value of oil exports of 42.1% (twice as much as total exports), which, combined with a deterioration in the price of a barrel of oil, meant a 40.9% reduction in public revenue from the oil sector, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) data .

The figures for the first two months of 2021 indicate an accentuation of the fall in crude oil production (-4.73% compared to January and February 2020) and derivatives (-7.47%), as well as their export (-22.8%).

Cutting expense and seeking oil revenues

Exiting OPEC did not pose any particular risk for Ecuador, which had already left the organisation in a previous period. Its limited weight in OPEC and the progressive decline in the cartel's own strength meant that Ecuador's attempt to go it alone was not particularly costly. The absolute priority of Lenín Moreno's government was to rebalance the country's macroeconomic picture - battered by the high public expense of his predecessor, Rafael Correa - and for this it urgently needed to increase state revenue, a significant part of which in Ecuador normally comes from the hydrocarbons sector.

When he became president in 2017, Moreno set out to steer the country towards more market-friendly energy policies. The president was determined to break with the nationalist approach of his predecessor, whose policies discouraged foreign investment in the oil industry while significantly increasing public debt. Among the most costly programmes undertaken by Correa was to maintain high subsidies for energy consumption, with especially low fuel prices.

In order to overcome the financial status that Ecuador found itself in when he took office, Moreno approached the IMF to apply for financial aid financial, and committed to structural reforms, including the gradual dismantling of subsidies. These reforms, however, were not well received and the social unrest that spread throughout the country put further pressure on the oil industry.

In February 2019, Moreno negotiated an IMF loan to help reduce the country's large fiscal deficit and huge external debt, which by the end of 2018 had reached 46.1 per cent of GDP and twelve months later would reach 51.8 per cent. The committed 'bailout' was for $10.2 billion, of which $6.5 billion came from the IMF and the rest from other international agencies.

As part of austerity measures agreed with the IMF, Moreno was forced to end government subsidies that had kept petrol prices low for decades. In early October 2019 he announced a plan of cuts to save $2.27 billion a year, essentially withdrawing the fuel subsidy. The advertisement decree, which would later be annulled, immediately provoked massive protests, both from transporters and low-income sectors, as well as most notably from indigenous communities. The street violence forced the president to leave Quito for a few days and move to Guayaquil.

To address the need for revenue, Moreno sought to rely on the oil industry, which accounts for roughly a third of the country's total exports. He initially expressed the intention to seek a rise from the 545,000 barrels of crude oil produced at the time to almost 700,000 barrels a day.

goal One of the measures taken in this direction was to promote the development and the exploitation of the Ishpingo-Tiputini-Tambococha field, with the aim of increasing oil production by 90,000 barrels a day. This decision met with social rejection due to the environmental damage it could cause, as the Yasuní National Park, in the Ecuadorian Amazon, has been declared a protected area. The government then decided to postpone the expansion of production, first to 2021 and then to 2022. The civil service examination was especially led by indigenous communities, in a mobilisation that partly explains the success in the 2021 presidential elections of Yaku Pérez's indigenist Pachakutik movement, which almost made it to the second round.

Another measure was to reverse some of his predecessor's emblematic policies. For example, he eliminated the service contracts introduced under President Correa, thus restoring the model production-sharing contract. This reform was more favourable to international oil companies, as it allowed them to retain a share of oil reserves; it also offered them financial incentives to invest in the country. The new model was first applied in the tenders awarded during the twelfth Intracampos oil round, in the Oriente region, which is rich in oil reserves. Under this contract modality , the Moreno administration awarded seven of the eight exploration blocks on offer with a total investment of more than $1.17 billion.

Fall in production

Due to the urgency of increasing revenues, Ecuador resisted the plan of production cuts that OPEC has been imposing on its members at various times since the abrupt fall in oil prices in 2014. Initially, the organisation accepted that some of its members, with moderate or very low production volumes compared to previous figures, as was the case of Venezuela, would maintain their extraction rates. But since it could no longer be an exception, Ecuador preferred to announce at the end of 2019 that it would leave OPEC and not have to reduce its production to 508,000 barrels per day in 2020, which was the quota set for it.

What is striking is that last year production finally fell from 528,000 barrels per day in 2019 to 472,000 (a drop of 10.8%), and not because of decisions taken at OPEC headquarters in Vienna but because of the various difficulties subject caused by the Covid-19 crisis. Petroecuador's oil exports fell from 331,321 barrels per day in 2019 to 316,000, a drop of 4.6%, which in monetary terms was greater, as the price of a barrel of Ecuadorian mixed oil fell from 55.3 dollars in 2019 to 34.7 in 2020.

One element that makes it difficult for Ecuador to take better advantage of its hydrocarbon potential is that it has insufficient infrastructure for refining crude oil. The country has three refineries, but their capacity does not reach the volume of domestic consumption of oil derivatives, which means that it must import diesel, naphtha and other products. This means that in times of high oil prices, Ecuador benefits from exports, but also has to pay a higher invoice price for imports of derivatives. In 2020, Petroecuador had to import 137,300 barrels per day.

The complicated situation caused by the pandemic has continued to put pressure on Ecuador's public debt, which reached 66.4% at the end of 2020, despite all the attempts made by the Moreno government to reduce it.

The next president, due to take office at the end of May 2021, will also have little room for manoeuvre due to these debt volumes and will have to continue to rely on higher oil revenues to balance public finances. The expansionary policies of expense during Correa's presidency took place in the context of the commodity super-cycle, which benefited South America so much, but this is unlikely to be repeated in the short term deadline.

OPEC's loss of weight

With its departure from OPEC, Ecuador left an international organisation that was created in 1960 with the aim of regulating the world oil market and controlling oil prices to a certain extent. goal . The founding members were Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. Over time, other countries joined OPEC and today it is made up of thirteen members: Algeria, Angola, Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Libya, Nigeria, United Arab Emirates and the five founding countries. When it was created, the organisation sought to establish, acting as a cartel, a kind of counterweight to a series of Western energy transnationals, mainly from the United States and the United Kingdom. OPEC members account for about 40 per cent of world oil production and contain about 80 per cent of the world's proven oil reserves. To be admitted as a member of the organisation it is necessary to have substantial oil exports and to share those of the member countries.

Ecuador joined OPEC in 1973, but suspended its membership in 1992. Subsequently, in 2007 it resumed active participation until its leave in January 2020. Considering that Ecuador was one of OPEC's smaller members, it did not really have much influence in the organisation and its exit does not represent a substantial loss for the organisation. However, it is a second departure in just one year, as Qatar, which had more weight in the cartel, left on 1 January 2019. In its case, its divorce from OPEC was due to other reasons, such as its tensions with Saudi Arabia and its desire to focus on the gas sector, of which it is one of the world's largest producers.

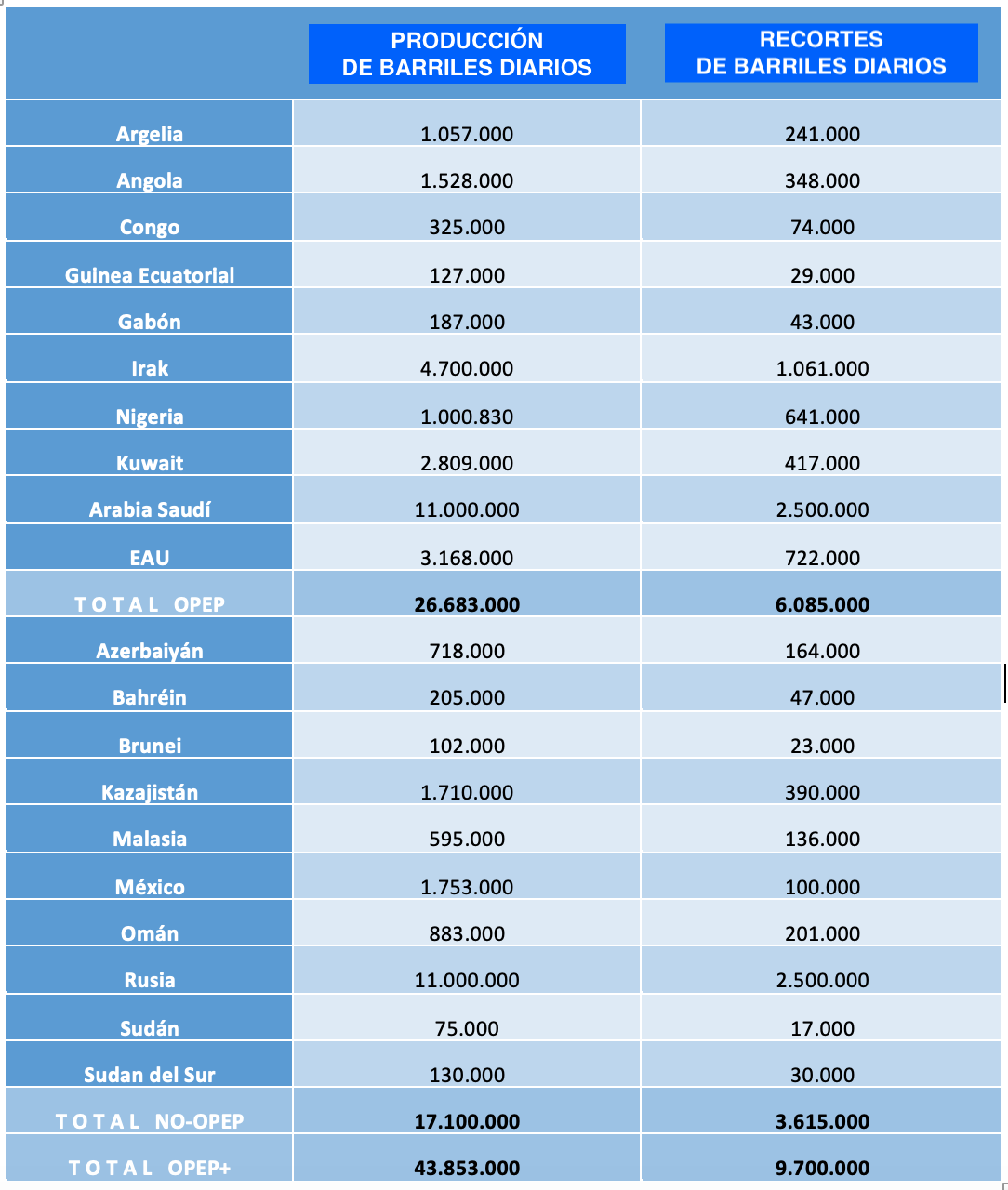

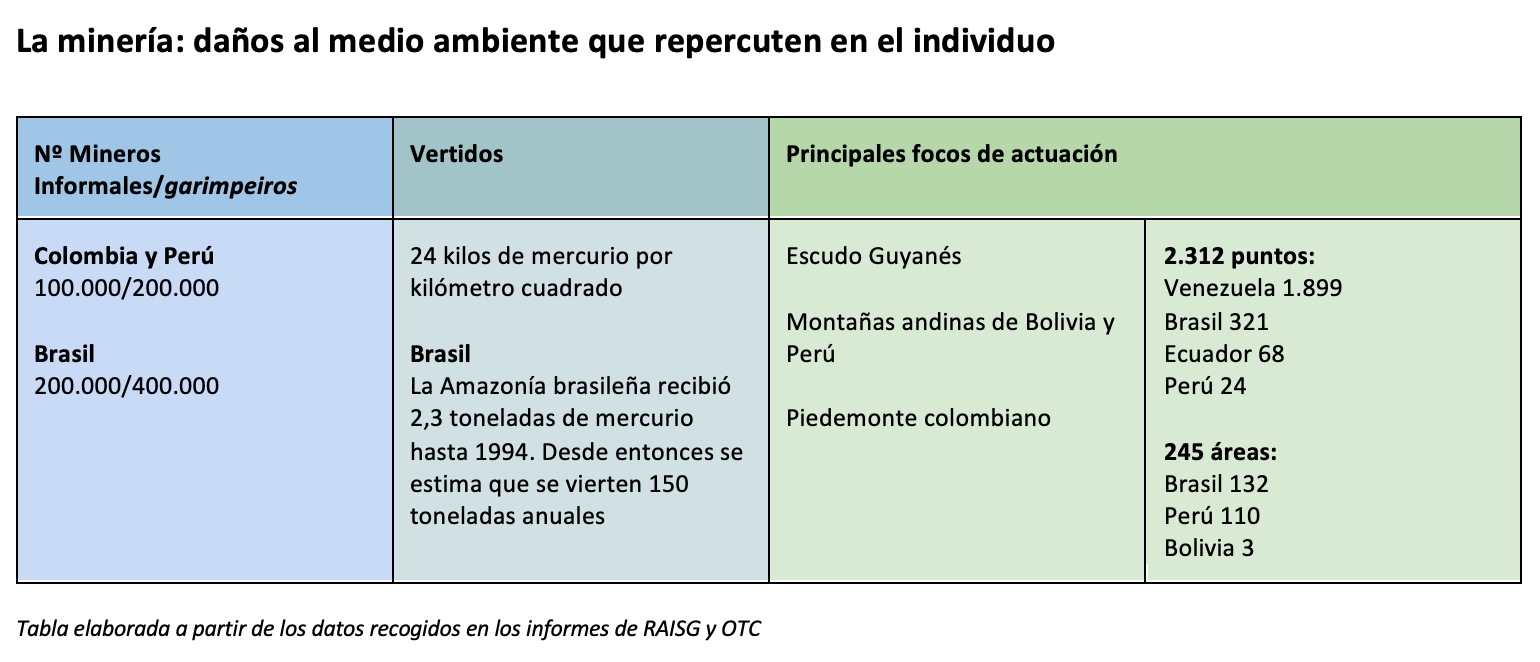

These moves are an example of OPEC's loss of influence. This has led it to establish alliances with producers that are not part of the organisation, such as Russia and some other countries forming OPEC+. With the decline of oil production in Venezuela and the decreasing ability of other members to control their production and exports, Saudi Arabia has been increasingly consolidating its position as the cartel's leader, accounting for around a third of the total production, with approximately 9.4 million barrels per day. In a way, Saudi Arabia and Russia remain, in a head to head battle, as the main countries seeking to cut production in an attempt to increase prices. Additionally, thanks to fracking, the United States has become the largest oil producer, representing a major influence on the international crude oil market, affecting the power that OPEC may have.

The hydrocarbon field is the centrepiece of President Alberto Fernández's 2020-2023 Gas Plan, which subsidises part of the investment.

Activity of YPF, Argentina's state-owned hydrocarbon company [YPF].

ANALYSIS / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa

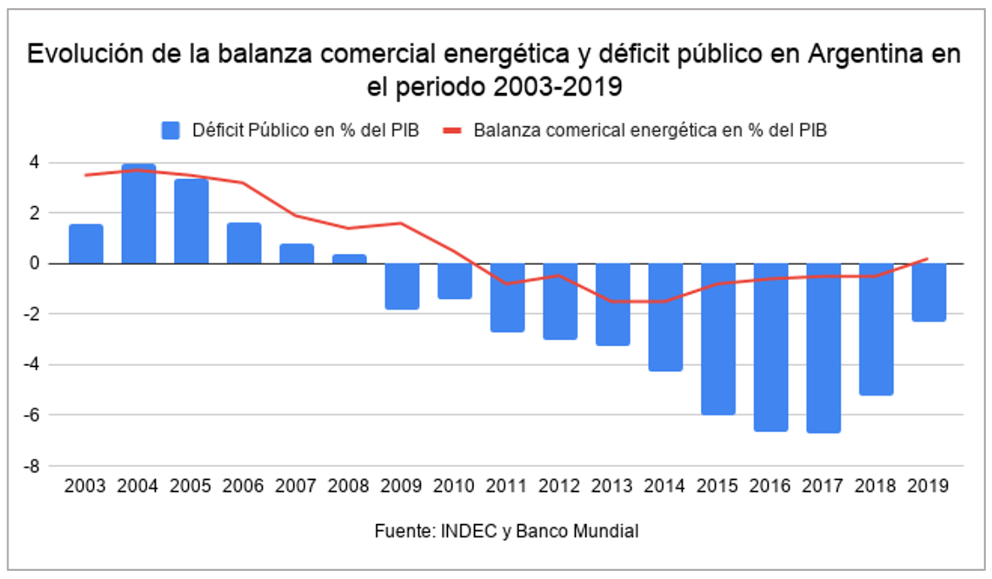

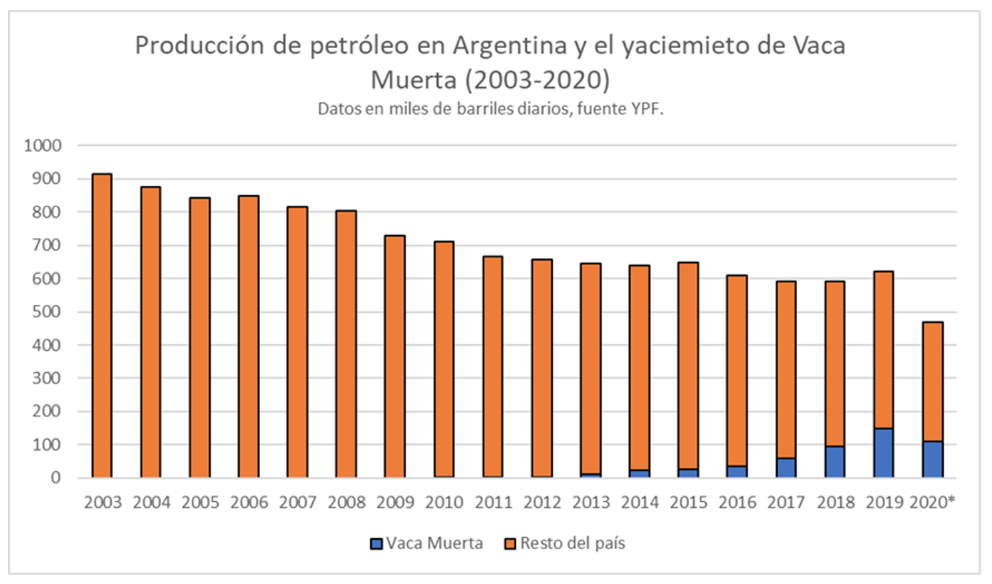

Argentina is facing a deep economic crisis that is having a severe impact on the standard of living of its citizens. The country, which had managed to emerge with enormous sacrifices from the corralito of 2001, sees its leaders committing the same macroeconomic recklessness that led the national Economics to collapse. After a hugely disappointing mandate by Mauricio Macri and his economic "gradualism", the new administration of Alberto Fernández has inherited a very delicate status , now aggravated by the global and national crisis generated by Covid-19. Public debt is now almost 100% of GDP, the Argentine peso is worth less than 90 units to the US dollar, while the public deficit persists. The Economics is still in recession, accumulating four years of decline. The IMF, which lent nearly $44 billion to Argentina in 2018 in the largest loan in the institution's history, has begun to lose patience with the lack of structural reforms and hints of debt restructuring by the government. In this critical status , Argentines are looking to the development unconventional oil industry as a possible way out of the economic crisis. In particular, the Vaca Muerta super field has been the focus of attention of international investors, government and citizens for the last decade, being a very promising project not Exempt of environmental and technical challenges.

The energy sector in Argentina: a history of fluctuations

The oil sector in Argentina has more than 100 years of history since oil was discovered in the Patagonian desert in 1907. The geographical difficulties of area - lack of water, distance from Buenos Aires and salty winds of more than 100 km/h - meant that project advanced very slowly until the outbreak of the First World War. The European conflict interrupted coal imports from England, which until then had accounted for 95% of Argentina's energy consumption. business The emergence of oil in the inter-war period as a strategic raw subject commodity revalued the sector, which began to receive huge foreign and domestic investment in the 1920s. By 1921, YPF, the first state-owned oil company in Latin America, was created, with energy self-sufficiency as its main goal goal. The country's political upheaval during the so-called Década Infame (1930-43) and the effects of the Great Depression damaged the incipient oil sector. The years of Perón's government saw a timid take-off of the oil industry with the opening of the sector to foreign companies and the construction of the first oil pipelines. In 1958, Arturo Frondizi became President of Argentina and sanctioned the Hydrocarbons Law of 1958, achieving an impressive development of the sector in only 4 years with an immense policy of public and private investment that multiplied oil production threefold, extended the network of gas pipelines and generalised access to natural gas for industry and households. The oil regime in Argentina kept the ownership of resource in the hands of the state, but allowed the participation of private and foreign companies in the production process.

Since the successful 1960s in subject oil, the sector entered a period of relative stagnation in parallel with Argentina's chaotic politics and Economics at the time. The 1970s was a complex journey in the desert for YPF, mired in huge debt and unable to increase production and secure the longed-for self-sufficiency.

The so-called Washington Consensus and the arrival of Carlos Menem to the presidency in 1990 saw the privatisation of YPF and the fragmentation of the state monopoly over the sector. By 1998, YPF was fully privatised under the ownership of Repsol, which controlled 97.5% of its capital. It was in the period 1996-2003 that peak oil production was reached, exporting natural gas to Chile, Brazil and Uruguay, and exceeding 300,000 barrels of crude oil per day in net exports.

However, a turnaround soon began in the face of state intervention in the market. Domestic consumption with fixed sales prices for oil producers was less attractive than the export market, encouraging private companies to overproduce in order to export oil and increase revenues exponentially. With the rise in oil prices of the so-called "commodity super-cycle" during the first decade of this century, the price differential between exports and domestic sales widened, creating a real incentive to focus on production. Exploration was thus left in the background, as domestic consumption grew rapidly due to tax incentives and a near horizon was foreseen without the possibility of exports and, therefore, lower income from the increase in reserves.

The exit from the 2001 crisis took place in a context of fiscal and trade surpluses, which allowed the country to regain the confidence of international creditors and reduce the volume of public debt. It was precisely the energy sector that was the main driver of this recovery, accounting for more than half of the trade surplus in the period 2004-2006 and one of Argentina's main sources of fiscal revenue. However, as mentioned above, this production was not sustainable due to the existence of a fiscal framework that distorted oil companies' incentives in favour of immediate consumption without investing in exploration. By 2004, a new tariff was applied to crude oil exports that floated on the basis of the international price of crude, reaching 45% if the price was above 45 dollars. The excessively rentier approach of Néstor Kirchner's presidency ended up dilapidating the sector's investment incentives, although it is true that they allowed for a spectacular increase in derived fiscal revenues, boosting Argentina's generous social and debt repayment plans. sample As a good illustration of this decline in exploration, in the 1980s more than 100 exploratory wells were drilled annually, in 1990 the figure exceeded 90, and by 2010 the figure was 26 wells per year. This figure is particularly dramatic if one takes into account the dynamics that the oil and gas sector tends to follow, with large investments in exploration and infrastructure in times of high prices, as was the case between 2001-2014.

In 2011, after a decade of debate on the oil sector in Argentina, President Cristina Fernández decided to expropriate 51 per cent of the shares of YPF held by Repsol, citing reasons of energy sovereignty and the decline of the sector. This decision followed the line taken by Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales in 2006 to increase the state's weight in the hydrocarbons sector at a time of electoral success for the Latin American left. The expropriation took place in the same year that Argentina became a net energy importer and coincided with the finding of the large shale reserves in Neuquén precisely by YPF, now known as Vaca Muerta. YPF at the time was the direct producer of approximately one third of Argentina's total volume. The expropriation took place at the same time as the imposition of the "cepo cambiario", a system of capital controls that made private foreign investment in the sector even less attractive. Not only was the country unable to recover its energy self-sufficiency, but it also entered a period of intense imports that hampered access to dollars and produced a large part of the macroeconomic imbalance of the current economic crisis.

The arrival of Mauricio Macri in 2015 heralded a new phase for the sector with policies more favourable to private initiative. One of the first measures was to establish a fixed price at the "wellhead" of the Vaca Muerta oil fields with the idea of encouraging the start-up of projects. As the economic crisis worsened, the unpopular measure of increasing electricity and fuel prices by more than 30 per cent was chosen, generating enormous discontent in the context of a constant devaluation of the Argentine peso and the rising cost of living. The energy portfolio was marked by enormous instability, with three different ministers who generated enormous legal insecurity by constantly changing the hydrocarbons regulatory framework . Renewable solar and wind energy, boosted by a new energy plan and greater liberalisation of investment, managed to double their energy contribution during Mauricio Macri's time in the Casa Rosada.

Alberto Fernández's first years have been marked by unconditional support for the hydrocarbons sector, with Vaca Muerta being the central axis of his energy policy, announcing the 2020-2023 Gas Plan that will subsidise part of the investment in the sector. On the other hand, despite the context of the health emergency, 39 renewable energy projects were installed in 2020, with an installed capacity of around 1.5 GW, an increase of almost 60% over the previous year. In any case, the continuity of this growth will depend on access to foreign currency in the country, which is essential to be able to buy panels and windmills from abroad. The boom in renewable energy in Argentina led the Danish company Vestas to install the first windmill assembly plant in the country in 2018, which already has several plants producing solar panels to supply domestic demand.

Characteristics of Vaca Muerta

Vaca Muerta is not a field from a technical point of view, it is a sedimentary training of enormous magnitude with dispersed deposits of natural gas and oil that can only be exploited with unconventional techniques: hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. These characteristics make Vaca Muerta a complex activity, which requires attracting as much talent as possible, especially from international players with experience in the exploitation of unconventional hydrocarbons. Likewise, conditions in the province of Neuquén are complex given the scarcity of rainfall and the importance of the fruit and vegetable industry, in direct competition with the water resources required for the exploitation of unconventional oil.

Since finding, the potential of Vaca Muerta has been compared to that of the Eagle Ford basin in the United States, which produces more than one million barrels per day. Evidently, the Neuquén region has neither Texas' oil business ecosystem nor its fiscal facilities, making what might be geologically similar in reality two totally different stories. In December 2020, Vaca Muerte produced 124,000 barrels of oil per day, a figure that is expected to gradually increase over the course of this year to 150,000 barrels per day, about 30% of the 470,000 barrels per day Argentina produced in 2020. Natural gas follows a slower process, pending the development of infrastructure that will allow the transport of large volumes of gas to consumption and export centres. In this regard, Fernández announced in November 2020 the Plan for the Promotion of Argentine Gas Production 2020-2023, with which the Casa Rosada seeks to save dollars by substituting imports. The plan facilitates the acquisition of dollars for investors and improves the maximum selling price of natural gas by almost 50%, to 3.70 dollars per mbtu, in the hope of receiving the necessary investment, estimated at 6.5 billion dollars, to achieve gas self-sufficiency. Argentina already has the capacity to export natural gas to Chile, Uruguay and Brazil through pipelines. Unfortunately, the floating vessel exporting natural gas from Vaca Muerte left Argentina at the end of 2020 after YPF unilaterally broke the ten-year contract with the vessel's owner, Exmar, citing economic difficulties, limiting the capacity to sell natural gas outside the continent.

One of the great advantages of Vaca Muerta is the presence of international companies with experience in the aforementioned US unconventional oil basins. The post-2014 learning curve of the US fracking sector is being applied in Vaca Muerta, which has seen drilling costs fall by 50% since 2014 while gaining in productivity. The influx of US capital may accelerate if Joe Biden's administration fiscally and environmentally restricts oil activities in the country, from agreement with its environmentalist diary . Currently the main operator in Vaca Muerta after YPF is Chevron, followed by Tecpetrol, Wintershell, Shell, Total and Pluspetrol, in an ecosystem with 18 oil companies working in different blocks.

Vaca Muerta as a national strategy

It is clear that achieving energy self-sufficiency will help Argentina's macroeconomic problems, the main headache for its citizens in recent years. No Exempt of environmental risk, Vaca Muerta could be a lifeline for a country whose international credibility is at an all-time low. Alberto Fernández's pro-hydrocarbon narrative follows the line of his Mexican counterpart Andrés guide López Obrador, with whom he intends to lead a new moderate left-wing axis in Latin America. The spectre of the nationalisation of YPF by the now vice-president Cristina Fernández, as well as the recent breach of contract with Exmar, continue to generate uncertainty among international investors. status Moreover, the poor financial performance of YPF, the main player in Vaca Muerta, with a debt of more than 8 billion dollars, is a major drag on the country's oil prospects. Similarly, Vaca Muerta is far from realising its potential, with significant but insufficient production to guarantee revenues that would bring about a radical change in Argentina's economic and social status . In order to guarantee its success, a context of favourable oil prices and the fluid arrival of foreign investors are needed. Two variables that cannot be taken for granted given Argentina's political context and the increasingly strong decarbonisation policy of traditional oil companies.

The big question now is how to reconcile the large-scale fossil fuel development with Argentina's latest commitments on climate change subject : to reduce CO2 emissions by 19% by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Similarly, the promising trajectory of renewable energy development during Mauricio Macri's presidency may lose momentum if the oil and gas sector attracts public and private investment, crowding out solar and wind.

Vaca Muerta is likely to advance slowly but surely as international oil prices stabilise upwards. The possibility of generating foreign currency and boosting a Economics on the verge of collapse should not be underestimated, but expecting Vaca Muerta to solve Argentina's problems on its own can only end in a new episode of frustration in the southern country.

Could Spain partner up with Morocco in the field of solar energy?

The two countries are greatly exposed to solar radiation and they already share electricity interconnectors.

The two countries are greatly exposed to solar radiation and they already share electricity interconnectors.

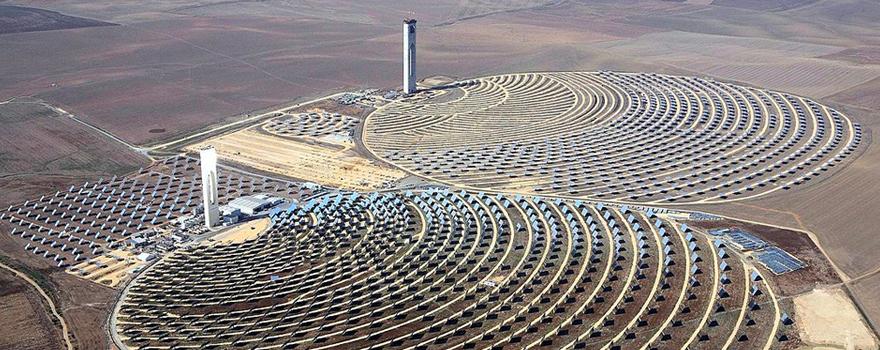

Spain was an early developer of solar energy, but it didn't keep the pace with the required investments. The effort in renewables should mean a clear increase in installed capacity for solar energy. A partnership with Morocco, gifted with even stronger solar resources, could benefit both countries in producing and marketing this particular renewable energy. Spain and Morocco are about to have a third electricity interconnector.

ARTICLE / Ane Gil

Spain has a lot of potential in solar energy. Currently, its Germany who produces more photovoltaic electricity than Spain, Portugal or Italy in Europe. In fact, in 2019, Germany produced five times more solar energy than Spain (50 GW of installed capacity versus just 11 GW). This fact has little to do with the raw solar energy that the countries receive, considering that Spain is located in Southern Europe.

For how much solar irradiation Spain receives, the solar energy it produces is scarce. Up until 2013, the installed capacity for solar energy grew rapidly. However, since then, the country has fallen behind many other European countries in the development of capacity. The country initially had a leading role in the development of solar power, with low prices that encouraged a boom in solar power installed capacity. However, because of the 2008 financial crisis, the Spanish government drastically cut its subsidies for solar power and limited any future increases in capacity to 500 MW per year. Between 2012 and 2016, Spain was left waiting while other countries developed. The cost of this was high, seeing as Spain lost much of its world leading status to countries such as Germany, China and Japan.

However, as a legacy from Spain's earlier development of solar power, in 2018 Spain became the first country in the world using concentrated solar power system (CSP), which accounts for almost a third of solar power installed capacity in the country. Nevertheless, in 2019, Spain installed 4,752 MW of photovoltaic solar energy, which situated Spain as the sixth leading country in the world. As of 2019, Spain has a total installed solar generation capacity of 11,015 MW: 8,711 of photovoltaic energy and 2,304 of solar thermal.

Photovoltaic solar (PV) energy is usually used for smaller-scale electricity projects. The devices generate electricity directly from sunlight via an electronic process that occurs naturally on semiconductors, converting it into usable electricity that can be stored in a solar battery of sent to the electric grid. Solar thermal energy (STE) capture is usually used for electricity production on a massive scale, for its use in the industry.

Low solar energy generated in Spain

By 2020, Spain national system has reached the maximum generation capacity ever recorded: 110,000 MW of wind energy, photovoltaic (PV), hydraulic, conventional thermal power (natural gas, coal, fuel oil), nuclear, etc. This amount of energy contrasts with the increasingly thin demand of power, which in 2019 was 40,000 MW (40 GW). According to the data published by network Electrica de España, the renewable quota of energy amount to a total of 55,247 MW (55 GW out of 110 GW). This 55 GW is composed of 46% corresponding to wind energy, 16% are photovoltaic and the rest (38%) corresponds to other renewable technologies. During 2019, the national renewable production has been 97,826 GW-hour, which represents 37.5% of the kilowatt-hour that the country demanded last year (the remaining 62.5% has been produced in nuclear power plants or facilities that burn fossil fuels).

So, we can clearly see that the percentage of solar energy is extremely low (3,5% solar photovoltaic and 2% solar thermic of the total kilowatts-hour generated). Nevertheless, Spain has the capability to increase these numbers. According to a report on power potential by country published by the World Bank, Spain has a long-term energy availability of solar resource at any location (average theoretical potential) of 4.575 kilowatts-hour per square metre (kWh/m2). This potential is indicated by the variable of global horizontal irradiation (GHI) on the country, which will vary according to the local factors of the land. Furthermore, the power output achievable by a typical PV system, taking into consideration the theoretical potential and the local factors of the land (average practical potential) is 4.413 kWh, excluding areas due to physical/technical constraints (rugged terrain, urbanized/industrial areas, forests...) PV power output (PVOUT), power generated per unit of the installed PV capacity over the long-term, is an average of 1.93 kilowatt-hours per installed kilowatt-peak of the system capacity (kWh/kWp). It varies according to the season from 1.43 to 2.67 kWh/kWp. Finally, it's worth mentioning that Spain's electric consumption (balance of production and external trade) in 2019 was of 238 TWh (= 2.38 x1011 kWh).

![The colours indicate the average solar radiation; the black dots indicate places where there could be a greater use of solar energy [Mlino76].](/documents/16800098/0/energia-solar-mapa.png/f4078864-e508-b667-31fc-d8b9e9bb68e1?t=1621870347022&imagePreview=1)

Morocco's solar energy plan

Africa is the continent that receives most solar irradiance, thus being the optimal continent to exploit solar energy. In this regard, Morocco is already aiming to take advantage of this natural resource. At first, this country launched a solar energy plan with investment of USD 9 billion, aiming to generate 2,000 MW (or 2 GW) of solar power by 2020. It has developed mega-scale solar power projects at five locations; at the Sahara (Laayoune), Western Sahara (Boujdour), South of Agadir (Tarfaya), Ain Beni Mathar and Ouarzazate. But Morocco is planning to go further. Morocco announced during COP21 that it planned to increase the renewables capacity to reach 52% of the total by 2030 (20% solar, 20% wind, 12% hydro). To meet the 2030 target, the country aims to add around 10 GW of renewable capacities between 2018 and 2030, consisting of 4,560 MW of solar, 4,200 MW of wind, and 1,330 MW of hydropower capacity. The Moroccan Agency for Renewable Energy revealed that by the end of 2019, Morocco's renewable energy reached 3,685 megawatts (MW), including 700 MW of solar energy, 1,215 MW of wind power, and 1,770 MW of hydroelectricity.

Now, what would happen if Spain partnered up with Morocco? Morocco is the only African country to have a power cable link to Europe. In fact, it's through Spain that these two electricity interconnectors arrive to Europe. The first subsea interconnection, with a technical capacity of 700 MW, was commissioned in 1997 and started commercial operation in 1998. The second was commissioned in the summer of 2016. Furthermore, a new interconnection had been commissioned. This should not only reduce the price of electricity in the Spanish market but it should also allow the integration of renewable energy, mainly photovoltaic, into European electricity system.

Moreover, network Electrica de España (REE) stated that a collaborations agreement between the Spain and Morocco had been formed "to establish a strategic partnership on energy, whose objectives will be focused on the integration of networks and energy markets, the development of renewable energy and energy efficiency". But the possibilities don't stop there. If both countries further develop their solar energy capacities, they could jointly provide enough electricity to sustain Europe, through sustainable and renewable resources.

US LNG sales to its neighbours and exports from Latin American and Caribbean countries to Europe and Asia open up new prospects

Not relying on pipelines, but being able to buy or sell natural gas also to distant or land-locked countries improves the energy prospects of many nations. The success of fracking has generated a surplus of gas that the US has begun to sell in many parts of the world, including to its hemispheric neighbours, who in turn have more choice provider. At the same time, being able to submit gas in tankers has expanded the customer portfolio of Peru and above all Trinidad and Tobago, which until last year were the only two American countries, apart from the US, with liquefaction plants. Argentina joined them in 2019, and Mexico in 2020 has promoted investments to join this revolution.

![A liquefied natural gas (LNG) freighter [Pline]. A liquefied natural gas (LNG) freighter [Pline].](/documents/16800098/0/gas-natural-blog.jpg/bc7b4699-c26c-a2d1-2971-f57cbb0345b8?t=1621873574093&imagePreview=1)

▲ A liquefied natural gas (LNG) freighter [Pline].

article / Ann Callahan

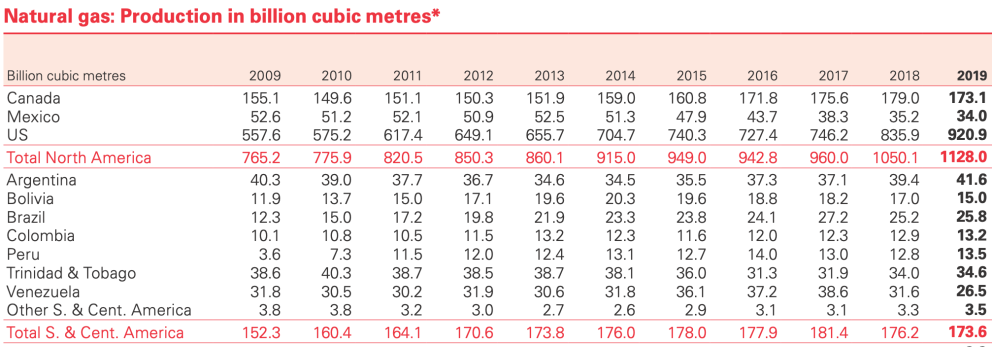

The United States is connected by pipeline only to Canada and Mexico, but is selling gas by ship to some thirty other countries (Spain, for example, has become a major buyer). In 2019, the US exported 47.5 billion cubic metres of liquefied natural gas (LNG), of which one-fifth went to American neighbours, according to agreement with report BP 2020 on the sector.

Eight countries in Latin America and the Caribbean already have regasification plants for gas arriving by cargo ship in liquid form: there are three plants in Mexico and Brazil; two in Argentina, Chile, Jamaica and Puerto Rico, and one each in Colombia, the Dominican Republic and Panama, according to the annual summary association of LNG importing countries. In addition to the US, LNG also arrives in these countries from Norway, Russia, Angola, Nigeria and Indonesia. Two countries export LNG to various parts of the world: Trinidad and Tobago, which has three liquefaction plants, and Peru, which has one (another became operational in Argentina last year).

In an attempt to mitigate the risk of electricity shortages due to a decrease in hydropower production due to drought or other difficulties in accessing energy sources, many countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are turning to LNG. As a cleaner energy source, it is also an attractive option for countries already struggling with climate change. In addition, gas financial aid will help overcome the discontinuity of alternative sources, such as wind and solar power.

In the case of small island countries, such as those in the Caribbean, which for the most part lack energy sources, cooperation programmes for the development of LNG terminals can provide them with a certain independence from certain oil supplies, such as the influence exerted on them by Chavista Venezuela through Petrocaribe.

LNG is natural gas that has been liquefied (cooled to about -162°C) for storage and transport. The volume of natural gas in its liquid state is reduced by approximately 600 times compared to its gaseous state. The process makes it possible and efficient to transport it to places that cannot be reached by pipelines. It is also much more environmentally friendly, as the carbon intensity of natural gas is about 30% less than that of diesel or other heavy fuels.

The global natural gas market has evolved rapidly in recent years. Global LNG capacities are expected to continue to grow until 2035, led by Qatar, Australia and the US. According to BP's report on the sector, in 2019 the share of gas in primary energy reached an all-time high of 24.2%. Much of the growth in gas production in 2019, when it increased by 3.4%, was due to additional LNG exports. LNG exports last year grew by 12.7% to 485.1 billion cubic metres.

Liquefaction and regasification plants in the Americas [report GIIGNL].

Boom

While the United States lagged behind in gas production at the beginning of the first decade of this century, the shale boom since 2009 has led the US to exponentially increase gas extraction and play a key role in the global trade of the liquefied product. With the relatively easy transportation of LNG, the US has been able to export and ship it to many parts of the world, with Latin America, due to its proximity, being one of the regions that is feeling the shift the most. Of the 47.5 billion cubic metres of LNG exported by the US in 2019, 9.7 billion went to Latin America; the main destinations were Mexico (3.9 billion), Chile (2.3 billion), Brazil (1.5 billion) and Argentina (1 billion).

While the region has promising export potential, given its proven natural gas reserves, demand exceeds production and it must import. Venezuela is the country with the largest reserves in Latin America (although its gas power is smaller than its oil power), but its hydrocarbon sector is in decline and the largest production in 2019 came from Argentina, an emerging shale country, followed by Trinidad and Tobago. Brazil matched Venezuela's output, followed by Bolivia, Peru and Colombia. In total, the region produced 207.6 billion cubic metres, while its consumption was 256.1 billion.

Some countries receive gas by pipeline, as is the case of Mexico and Argentina and Brazil: the former receives gas from the US and the latter from Bolivia. But the growing option is to install regasification plants to receive liquefied gas; such projects require some investment, usually foreign. The largest exporter of LNG to the region in 2019 was the US, followed by Trinidad and Tobago, which, due to its low domestic consumption, exports practically all its production: of its 17 billion cubic metres of LNG, 6.1 billion went to Latin American countries. The third largest exporter is Peru, which sent its 5.2 billion cubic metres to Asia and Europe (it did not sell on the continent itself). Argentina joined exports in 2019 for the first time, although with a leave amount, 120 million cubic metres, almost all destined for Brazil.

The region imported a total of 19.7 billion cubic metres of LNG in 2019. The main buyers were Mexico (6.6 billion cubic metres), Chile (3.3 billion), Brazil (3.2 billion) and Argentina (1.7 billion).

Some of those that imported smaller quantities then re-exported part of the supplies, as did the Dominican Republic, Jamaica and Puerto Rico, generally with Panama as the main destination.

Tables extracted from report Statistical Review of World Energy 2020 [BP].

By country

Mexico is the largest importer of LNG in Latin America; its supplies come mainly from the US. For a long time, Mexico has relied on gas shipments from its northern neighbour via pipelines. However, the LNG development has opened up new prospects, as the country's location can help it boost both capacities: improved pipeline connections with the US may allow Mexico to have a gas surplus at Pacific terminals for re-exporting LNG to Asia, complementing the absence of liquefaction plants on the US West Coast for the time being.

The possibility of re-exporting from Mexico's Pacific coast to the large and growing Asian LNG market - without the need for tankers to pass through the Panama Canal - is a major attraction. agreement The US Energy department granted in early 2019 two authorisations to Mexico's project Energía Costa Azul to re-export US-derived natural gas in the form of LNG to those countries that do not have a free trade agreement (FTA) with Washington, as stated in the 2020 report of the group International Importers of Liquefied Natural Gas(GIIGNL).

For the past decade, Argentina has been importing LNG from the US; however, in recent years it has reduced its purchases by more than 20 per cent as domestic gas production has increased thanks to the exploitation of Vaca Muerta. These fields have also allowed it to reduce gas purchases from neighbouring Bolivia and sell more gas, also via pipeline, to its neighbours Chile and Brazil. In addition, in 2019 it will begin exporting LNG from the Bahía Blanca plant.

With Argentina pumping gas to neighbouring Chile, in 2019 Chilean LNG imports declined to their lowest Degree in three years, although it remains one of the important buyers in Latin America, having switched Trinidad and Tobago to the US as its preferred provider . It should be noted, however, that Argentina's export capacity depends on the levels of domestic flows, especially during winter seasons when widespread heating is a necessity for Argentines.

Over the past decade, Brazil' s LNG imports have varied significantly from year to year. However, it is projected to be more consistent in its reliance on LNG until at least the next decade, as renewable energy is developed. In Brazil, natural gas is largely used to back up Brazilian hydropower.

In addition to Brazil, Colombia also considers LNG as an advantageous resource to back up its hydroelectric system in low periods. On its Pacific coast, Colombia is currently planning a second regasification terminal. Ecopetrol, the state hydrocarbon business , will allocate USD 500 million to unconventional gas projects in addition to oil. Along with the government's authorisation to allow fracking, currently stagnant reserves are projected to increase.

Bolivia also has significant natural gas production potential and is the country in the region whose Economics is most dependent on this sector. It has the advantage of existing infrastructure and the size of neighbouring gas markets; however, it faces skill production from Argentina and Brazil. Also, being a landlocked country, it is limited in the commercialisation of LNG.

Although Peru is the seventh largest producer of natural gas in the region, it has become the second largest exporter of LNG. Lower domestic consumption, compared to other neighbouring markets, has led it to develop LNG exports, reinforcing its profile as a nation focused on Asia.

For its part, Trinidad and Tobago has adapted its gas production to its status as an island country, basing its hydrocarbon exports on tankers, which gives it access to distant markets. It is the leading exporter in the region and the only one with customers in all continents.

The finding of a "significant" amount of oil in offshore wells puts the former Dutch colony in the footsteps of neighbouring Guyana.

The intuition has proved to be correct, and explorations carried out under Suriname's territorial waters, together with the successful hydrocarbon reserves that are being exploited in Guyana's maritime borders, have found abundant oil. The finding could be a decisive boost for the development of what is, after Guyana, the second poorest country in South America, but it could also be an opportunity, as with its neighbour, to accentuate the economic and political corruption that has been hindering the progress of the population.

![Suriname's presidential palace in the country's capital, Paramaribo [Ian Mackenzie]. Suriname's presidential palace in the country's capital, Paramaribo [Ian Mackenzie].](/documents/10174/16849987/surinam-oil-blog.jpg)

Suriname's presidential palace in the country's capital, Paramaribo [Ian Mackenzie].

article / Álvaro de Lecea

So far this year, drilling in two offshore fields in Suriname has been positive result , confirming the existence of "significant" oil in block 58, operated by France's Total, in partnership with US-based Apache. Everything indicates that the same success could be obtained in block 52, operated by the also American ExxonMobil and the Malaysian Petronas, which were pioneers in prospecting in Surinamese waters with operations since 2016.

Both blocks adjoin the fields under the waters of neighbouring Guyana, where it is currently estimated that there are some 3.2 billion barrels of extractable oil. In the case of Suriname, exploration in the first viable field, Maka Central-1, discovered in January 2020, indicates 300 million barrels, but estimates from Sapakara West-1, discovered in April, and subsequent planned exploration, have yet to be added. It is estimated that some 15 billion barrels of oil reserves may exist in the Guyana-Suriname basin.

Until this new oil era in the Guianas (the former British and Dutch Guianas; the French Guianas remains an overseas dependency of France), Suriname was considered to have reserves of 99 million barrels, which at the current rate of exploitation left two decades to deplete. In 2016, the country produced just 16,400 barrels per day.

status political, economic and social

With just under 600,000 inhabitants, Suriname is the least populated country in South America. Its Economics is heavily dependent on the export of metals and minerals, especially bauxite. The fall in commodity prices since 2014 has particularly affected the country's accounts. GDP contracted by 3.4% in 2015 and by 5.6% in 2016. Although the trend then turned positive again, the IMF forecasts a 4.9% drop in GDP for 2020, as a result of the global crisis caused by Covid-19.

Since gaining independence from the Netherlands in 1975, its weak democracy has suffered three coups d'état. Two of them were led by the same person: Desi Bouterse, the country's president until this July. Bouterse staged a coup in 1980 and remained in power indirectly until 1988. During those years, he kept Suriname under a dictatorship. In 1990 he staged another coup d'état, although this time he resigned the presidency. He was accused of the 1982 murder of 15 political opponents, in a long judicial process that finally ended in December 2019 with a twenty-year prison sentence, which is now being appealed by Bouterse. He has also been convicted of drug trafficking in the Netherlands, for which the resulting international arrest warrant prevents him from leaving Suriname. His son Dino has also been convicted of drug and arms trafficking and is in prison in the United States. Bouterse's Suriname has come to be presented as the paradigm of the mafia state.

In 2010 Desi Bouterse won the elections as candidate of the National Democratic Party (NDP); in 2015 he was re-elected for another five years. In the 25 May elections, despite some controversial measures to limit the options of the civil service examination, he lost to Chan Santokhi, leader of the Progressive Reform Party (VHP). He tried to delay the counting and validation of votes, citing the health emergency caused by the coronavirus, but the new National Assembly was finally constituted at the end of June and is due to appoint the country's new president in July.

![Total's operations in Surinamese and Guyanese waters [Total]. Total's operations in Surinamese and Guyanese waters [Total].](/documents/10174/16849987/surinam-oil-mapa.png)

Total's operations in Surinamese and Guyanese waters [Total].

Relationship with Venezuela

Suriname intends to use the prospect of the oil bonanza to strengthen Staatsolie, the state oil company. In January, before the Covid-19 crisis became widespread, it announced purpose to expand its presence in the bond market in 2020 and also, conditions permitting, to list its shares in London or New York. This would serve to raise up to $2 billion to finance the national oil company's exploration campaign over the next few years.

On the other hand, Venezuela's territorial claims against Guyana, which affect the Essequibo - the western half of the former British colony - and which are being studied by the International Court of Justice, include part of the maritime space in which Guyana is extracting oil, but do not affect the case of Suriname, whose delimitations are outside the scope of this long-standing dispute.

Venezuela and Suriname have maintained special relations during Chavismo and while Desi Bouterse has been in power. On occasions, a certain connection has been made between drug trafficking under the protection of the Chavista authorities and that attributed to Bouterse. The offer made by Bouterse's son to Hezbollah to have training camps in Suriname, for which he was arrested in 2015 in Panama at the request of the United States and tried in New York, can be understood in light of the relationship between Chavism and Hezbollah, to whose operatives Caracas has provided passports to facilitate their movements. Suriname has supported Venezuela in regional forums at times of international pressure against the regime of Nicolás Maduro. In addition, the country has increasingly strengthened its relations with Russia and China, from which in December 2019 it secured the commitment of a new credit .

With the political change of the last elections, Maduro's Venezuela has in principle lost a close ally, while gaining an oil competitor (at least as long as Venezuelan oil exploitation remains at a low level).

![Flood rescue in the Afghan village of Jalalabad, in 2010 [NATO]. Flood rescue in the Afghan village of Jalalabad, in 2010 [NATO].](/documents/10174/16849987/climate-refugees-blog.jpg)

▲ Flood rescue in the Afghan village of Jalalabad, in 2010 [NATO].

ESSAY / Alejandro J. Alfonso

In December of 2019, Madrid hosted the United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP25, in an effort to raise awareness and induce action to combat the effects of climate change and global warming. COP25 is another conference in a long line of efforts to combat climate change, including the Kyoto Protocol of 2005 and the Paris Agreement in 2016. However, what the International Community has failed to do in these conferences and agreements is address the issue of those displaced by the adverse effects of Climate Change, what some call "Climate Refugees".

Introduction

In 1951, six years after the conclusion of the Second World War and three years after the creation of the State of Israel, a young organisation called the United Nations held an international convention on the status of refugees. According to Article 1 section A of this convention, the status of refugee would be given to those already recognized as refugees by earlier conventions, dating back to the League of Nations, and those who were affected "as a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion...". However, as this is such a narrow definition of a refugee, the UN reconvened in 1967 to remove the geographical and time restrictions found in the 1951 convention[1], thus creating the 1967 Protocol.

Since then, the United Nations General Assembly and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) have worked together to promote the rights of refugees and to continue the fight against the root causes of refugee movements. [2] In 2016, the General Assembly made the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, followed by the Global Compact on Refugees in 2018, in which four objectives were established: "(i) ease pressures on host countries; (ii) enhance refugee self-reliance; (iii) expand access to third country solutions; and (iv) support conditions in countries of origin for return in safety and dignity". [3] Defined as 'interlinked and interdependent objectives', the Global Compact aims to unite the political will of the International Community and other major stakeholders in order to have 'equitalized, sustained and predictable contributions' towards refugee relief efforts. Taking a holistic approach, the Compact recognizes that various factors may affect refugee movements, and that several interlinked solutions are needed to combat these root causes.

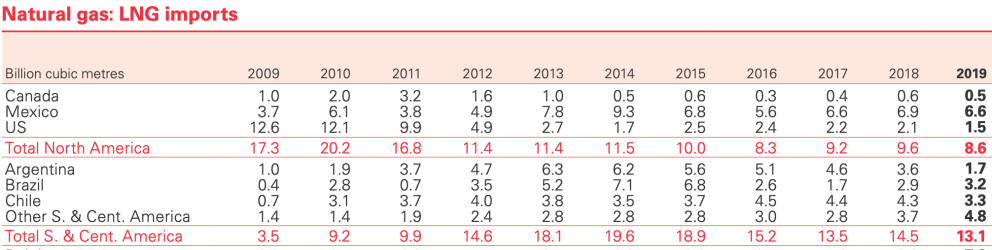

While the UN and its supporting bodies have made an effort to expand international protection of refugees, the definition on the status of refugees remains largely untouched since its initial applications in 1951 and 1967. "While not in themselves causes of refugee movements, climate, environmental degradation and natural disasters increasingly interact with the drivers of refugee movements".3 The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has found that the increase of the average temperature of the planet, commonly known as Global Warming, can lead to an increase in the intensity and occurrence of natural disasters[4]. Furthermore, this is reinforced by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, which has found that the number of those displaced by natural disasters is higher than the number of those displaced by violence or conflict on a yearly basis[5], as shown in Table 1. In an era in which there is great preoccupation and worry concerning the adverse effects of climate change and global warming, the UN has not expanded its definition of refugee to encapsulate those who are displaced due to natural disasters caused by, allegedly, climate change.

Table 1 / Global Internal Displacement Database, from IDMC

Methodology

This present paper will be focused on the study of Central America and Southeast Asia as my study subjects. The first reason for which these two regions have been selected is that both are the first and second most disaster prone areas in the world[6], respectively. Secondly, the countries found within these areas can be considered as developing states, with infrastructural, economic, and political issues that can be aggravating factors. Finally, both have been selected due to the hegemonic powers within those hemispheres: the United States of America and the People's Republic of China. Both of these powers have an interest in how a 'refugee' is defined due to concerns over these two regions, and worries over becoming receiving countries to refugee flows.

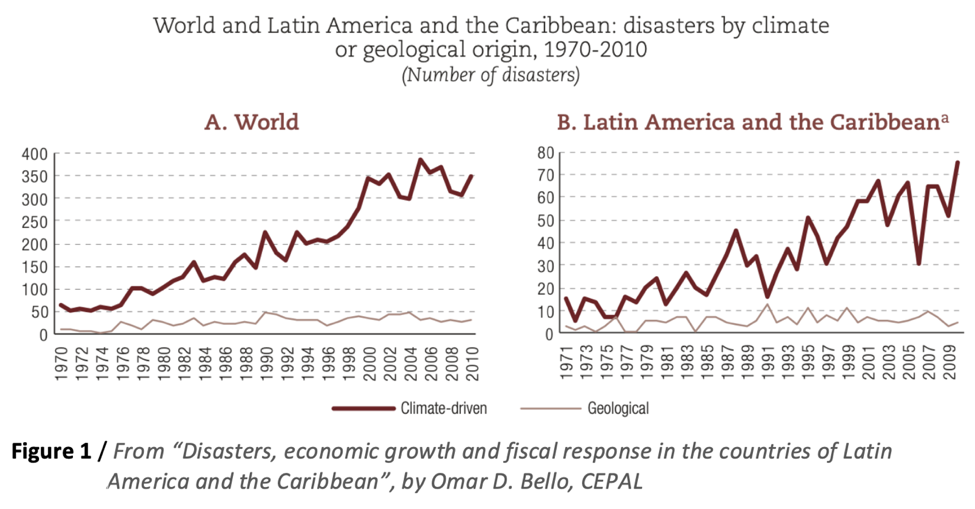

Central America

As aforementioned, the intensity and frequency of natural disasters are expected to increase due to irregularities brought upon by an increase in the average temperature of the ocean. Figure 1 shows that climate driven disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean have slowly been increasing since the 1970s, along with the world average, and are expected to increase further in the years to come. In a study by Omar D. Bello, the rate of climate related disasters in Central America increased by 326% from the year 1970 to 1999, while from 2000 to 2009 the total number of climate disasters were 143 and 148 in Central America and the Caribbean respectively[7]. On the other hand, while research conducted by Holland and Bruyère has not concluded an increase in the number of hurricanes in the North Atlantic, there has been an upward trend in the proportion of Category 4-5 hurricanes in the area[8].

This increase in natural disasters, and their intensity, can have a hard effect on those countries which have a reliance on agriculture. Agriculture as a percentage of GDP has been declining within the region in recent years due to policies of diversification of economies. However, in the countries of Honduras and Nicaragua the percentage share of agriculture is still slightly higher than 10%, while in Guatemala and Belize agriculture is slightly below 10% of GDP share[9]. Therefore, we can expect high levels of emigration from the agricultural sectors of these countries, heading toward higher elevations, such as the Central Plateau of Mexico, and the highlands of Guatemala. Furthermore, we can expect mass migration movements from Belize, which is projected to be partially submerged by 2100 due to rising sea levels[10].

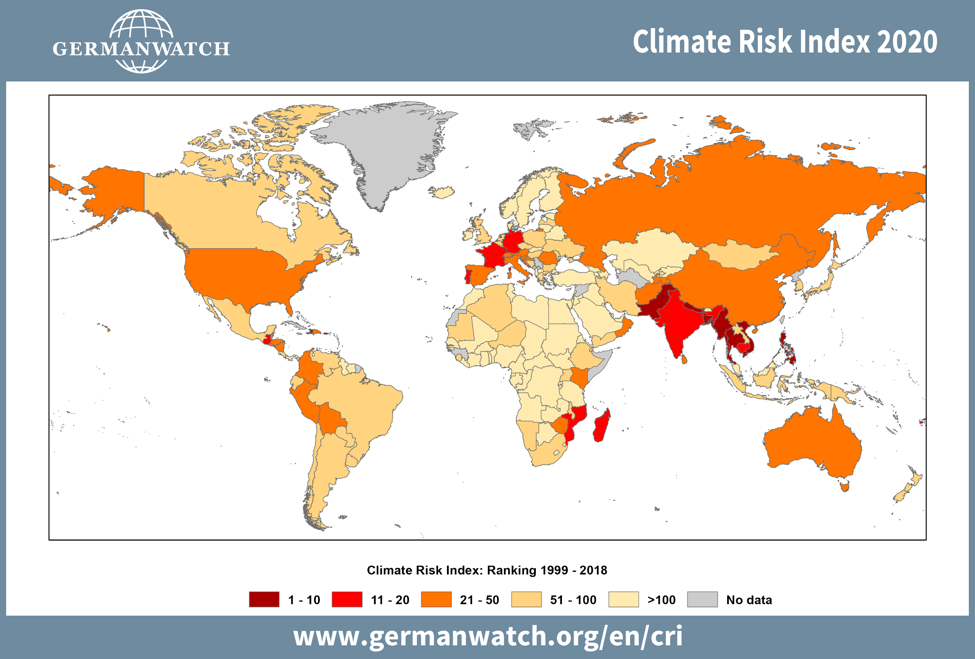

Figure 2 / Climate Risk Index 2020, from German Watch

Southeast Asia

The second region of concern is Southeast Asia, the region most affected by natural disasters, according to the research by Bello, mentioned previously. The countries of Southeast Asia are ranked in the top ten countries projected to be at most risk due to climate change, shown in Figure 2 above[11]. Southeast Asia is home to over 650 million people, about 8% of total world population, with 50% living in urban areas[12]. Recently, the OECD concluded that while the share in GDP of agriculture and fisheries has declined in recent years, there is still a heavy reliance on these sectors to push economy in the future[13]. In 2014, the Asian Development Bank carried out a study analysing the possible cost of climate change on several countries in the region. It concluded that a possible loss of 1.8% in the GDP of six countries could occur by 2050[14]. These six countries had a high reliance on agriculture as part of the GDP, for example Bangladesh with around 20% of GDP and 48% of the workforce being dedicated to agricultural goods. Therefore, those countries with a high reliance on agricultural goods or fisheries as a proportion of GDP can be expected to be the sources of large climate migration in the future, more so than in the countries of Central America.

One possible factor is the vast river system within the area, which is susceptible to yearly flooding. With an increase in average water levels, we can expect this flooding to worsen gradually throughout the years. In the case of Bangladesh, 28% of the population lives on a coastline which sits below sea level[15]. With trends of submerged areas, Bangladesh is expected to lose 11% of its territory due to rising sea levels by 2050, affecting approximately 15 million inhabitants[16][17]. Scientists have reason to believe that warmer ocean temperatures will not only lead to rising sea levels, but also an intensification and increase of frequency in typhoons and monsoons[18], such as is the case with hurricanes in the North Atlantic.

Expected Destinations

Taking into account the analysis provided above, there are two possible migration movements: internal or external. In respect to internal migration, climate migrants will begin to move towards higher elevations and temperate climates to avoid the extreme weather that forced their exodus. The World Bank report, cited above, marked two locations within Central America that fulfil these criteria: the Central Plateau of Mexico, and the highlands of Guatemala. Meanwhile, in Southeast Asia, climate migrants will move inwards in an attempt to flee the rising waters, floods, and storms.

However, it is within reason to believe that there will be significant climate migration flows towards the USA and the People's Republic of China (PRC). Both the United States and China are global powers, and as such have a political stability and economic prowess that already attracts normal migration flows. For those fleeing the effects of climate change, this stability will become even more so attractive as a future home. For those in Southeast Asia, China becomes a very desired destination. With the second largest land area of any country, and with a large central zone far from coastal waters, China provides a territorial sound destination. As the hegemon in Asia, China could easily acclimate these climate migrants, sending them to regions that could use a larger agricultural workforce, if such a place exists within China.

In the case of Central America, the United States is already a sought-after destination for migrant movements, being the first migrant destination for all Central American countries except Nicaragua, whose citizens migrate in greater numbers to Costa Rica[19]. With the world's largest economy, and with the oldest democracy in the Western hemisphere, the United States is a stable destination for any refugee. In regard to relocation plans for areas affected by natural disasters, the United States also has shown it is capable of effectively moving at-risk populations, such as the Isle de Jean Charles resettlement program in the state of Louisiana[20].

Problems

While some would opine that 'climate migrants' and 'climate refugees' are interchangeable terms, they are unfortunately not. Under international law, there does not exist 'climate refugees'. The problem with 'climate refugees' is that there is currently no political will to change the definition of refugee to include this new category among them. In the case of the United States, section 101(42) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), the definition of a refugee follows that of the aforementioned 1951 Geneva convention[21], once again leaving out the supposed 'climate refugees'. The Trump administration has an interest in maintaining this status quo, especially in regard to its hard stance in stopping the flow of illegal immigrants coming from Central America. If a resolution should pass the United Nations Security Council, the Trump administration would have no choice but to change section 101(42) of the INA, thus risking an increased number of asylum applicants to the US. Therefore, it can confidently be projected that the current administration, and possibly future administrations, would utilize the veto power, given to permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, on such a resolution.

China, the strongest regional actor in Asia, does not have to worry about displeasing the voter. Rather, they would not allow a redefinition of refugee to pass the UN Security Council for reasons concerning the stability and homogeneity of the country. While China does accept refugees, according to the UNHCR, the number of refugees is fairly low, especially those from the Middle East. This is mostly likely due to the animosity that the Chinese government has for the Muslim population. In fact, the Chinese government has a tense relationship with organised religion in and of itself, but mostly with Islam and Buddhism. Therefore, it is very easy to believe that China would veto a redefinition of refugee to include 'climate refugees', in that that would open its borders to a larger number of asylum seekers from its neighbouring countries. This is especially unlikely when said neighbours have a high concentration of Muslims and Buddhists: Bangladesh is 90% Muslim, and Burma (Myanmar) is 87% Buddhist[22]. Furthermore, both countries have known religious extremist groups that cause instability in civil society, a problem the Chinese government neither needs nor wants.

On the other hand, there is also the theory that the causes of climate migration simply cannot be measured. Natural disasters have always been a part of human history and have been a cause of migration since time immemorial. Therefore, how can we know if migrations are taking place due to climate factors, or due to other aggravating factors, such as political or economic instability? According to a report by the French think tank 'Population and Societies', when a natural disaster occurs, the consequences remain localised, and the people will migrate only temporarily, if they leave the affected zone at all[23]. This is due to the fact that usually that society will bind together, working with familial relations to surpass the event. The report also brings to light an important issue touched upon in the studies mentioned above: there are other factors that play in a migration due to a natural disaster. Véron and Golaz in their report cite that the migration caused by the Ethiopian drought of 1984 was also due in part to bad policies by the Ethiopian government, such as tax measures or non-farming policies.

The lack of diversification of the economies of these countries, and the reliance on agriculture could be such an aggravating factor. Agriculture is very susceptible to changes in climate patterns and are affected when these climate patterns become irregular. This can relate to a change of expected rainfall, whether it be delayed, not the quantity needed, or no rainfall at all. Concerning the rising sea levels and an increase in floods, the soil of agricultural areas can be contaminated with excess salt levels, which would remain even after the flooding recedes. For example, the Sula Valley in Honduras generates 62% of GDP, and about 68% of the exports, but with its rivers and proximity to the ocean, also suffers from occasional flooding. Likewise, Bangladesh's heavy reliance on agriculture, being below sea level, could see salt contamination in its soil in the near future, damaging agricultural property.

Reliance on agriculture alone does not answer why natural disasters could cause large emigration in the region. Bello and Professor Patricia Weiss Fagen[24] find that issues concerning the funding of local relief projects, corruption in local institutions, and general mismanagement of crisis response is another aggravating factor. Usually, forced migration flows finish with a return to the country or area of origin, once the crisis has been resolved. However, when the crisis has continuing effects, such as what happened in Chernobyl, for example, or when the crisis has not been correctly dealt with, this return flow does not occur. For example, in the countries composing the Northern Triangle, there are problems of organised crime which is already a factor for migration flows from the area[25]. Likewise, the failure of Bangladesh and Myanmar to deal with extremist Buddhist movements, or the specific case of the Rohinga Muslims, could inhibit return flows and even encourage leaving the region entirely.

Recommendations and Conclusions

The definition of refugee will not be changed or modified in order to protect climate migrants. That is a political decision by countries who sit at a privileged position of not having to worry about such a crisis occurring in their own countries, nor want to be burdened by those countries who will be affected. Facing this simple reality should help to find a better alternative solution, which is the continuing efforts of the development of nations, in order that they may be self-sufficient, for their sake and the population's sake. This fight does not have to be taken alone, but can be fought together through regional organisations who have a better understanding and grasp of the gravity of the situation, and can create holistic approaches to resolve and prevent these crises.

We should not expect the United Nations to resolve the problem of displacement due to natural disasters. The United Nations focuses on generalized and universal issues, such as that of global warming and climate change, but in my opinion is weak in resolving localized problems. Regional organizations are the correct forum to resolve this grave problem. For Central America, the Organization of American States (OAS) provides a stable forum where these countries may express their concerns with states of North and Latin America. With the re-election of Secretary General Luis Almagro, a strong and outspoken authority on issues concerning the protection of Human Rights, the OAS is the perfect forum to protect those displaced by natural disasters in the region. Furthermore, the OAS could work closely with the Inter-American Development Bank, which has the financial support of international actors who are not part of the OAS, such as Japan, Israel, Spain, and China, to establish the necessary political and structural reforms to better implement crisis management responses. This does not exclude the collusion with other international organizations, such as the UN. Interestingly, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has a project in the aforementioned Sula Valley to improve infrastructure to deal with the yearly floods[26].

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is another example of an apt regional organisation to deal with the localized issues. Mostly dealing with economic issues, this forum of ten countries could carry out mutual programs in order to protect agricultural territory, or further integrate to allow a diversification of their economies to ease this reliance on agricultural goods. ASEAN could also call forth the ASEAN +3 mechanism, which incorporates China, Japan, and South Korea, to help with the management of these projects, or for financial aid. China should be interested in the latter option, seeing as it can increase its good image in the region, as well as protecting its interest of preventing possible migration flows to its territory. The Asian Development Bank, on the other hand, offers a good alternative financial source if the ASEAN countries so choose, in order to not have heavy reliance on one country or the other.

[7]https://archive.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/42007/1/RVI121_Bello.pdf

[20] http://isledejeancharles.la.gov/

![proposal of a lunar base for obtaining helium, taken from ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt]. proposal of a lunar base for obtaining helium, taken from ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt].](/documents/10174/16849987/gaj-foto-3.jpg)

▲ proposal of a lunar base for obtaining helium, taken from ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt].

GLOBAL AFFAIRS JOURNAL / Emili J. Blasco

[8-page document. downloadin PDF]

[8-page document. downloadin PDF]

INTRODUCTION

The economic interest in space resources, or at least the reasonable expectation of the profitability of obtaining them, goes a long way to explaining the growing involvement of private investment in space travel.

Beyond the commercially strong artificial satellite industry, as well as those serving scientific and defence purposes, where the state sector continues to play a leading role, the possibility of exploiting high-value raw materials present on celestial bodies - from entrance, on the closest asteroids to the Earth and on the Moon - has awakened a kind of gold rush that is fuelling the new space degree program .

The epic of the new space barons - Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos - has captured the public narrative, but alongside them there are other New Space Players, with varied profiles. Behind them all is a growing group of equity partners and restless investors willing to risk assets in the hope of profit.

To talk of space mining fever is certainly exaggerated, as the real economic benefit to be gained from space mining - obtaining platinum, for example, or lunar helium - has yet to be demonstrated. While the technology is becoming cheaper, financially enabling new steps into outer space, bringing tons of materials back to Earth has a cost that in most cases makes the operation less financially meaningful.

It would be enough, however, that in certain situations it would be profitable to increase the number of space missions issue , and it is assumed that this traffic in itself would generate the need for an infrastructure abroad, at least with stations to refuel fuel - so expensive to lift into the sky - manufactured from subject raw materials found in space (the water at the lunar poles could be transformed into propellant). It is this expectation, with some basis in reasonableness, that is fuelling the investments being made.

In turn, increased space activity and the skill to obtain the resources sought project beyond our planet the concepts of geopolitics developed for Earth. The location of countries (there are particularly suitable locations for space launches) and the control of certain routes (the succession of the most convenient flight orbits) are part of the new astro-politics.

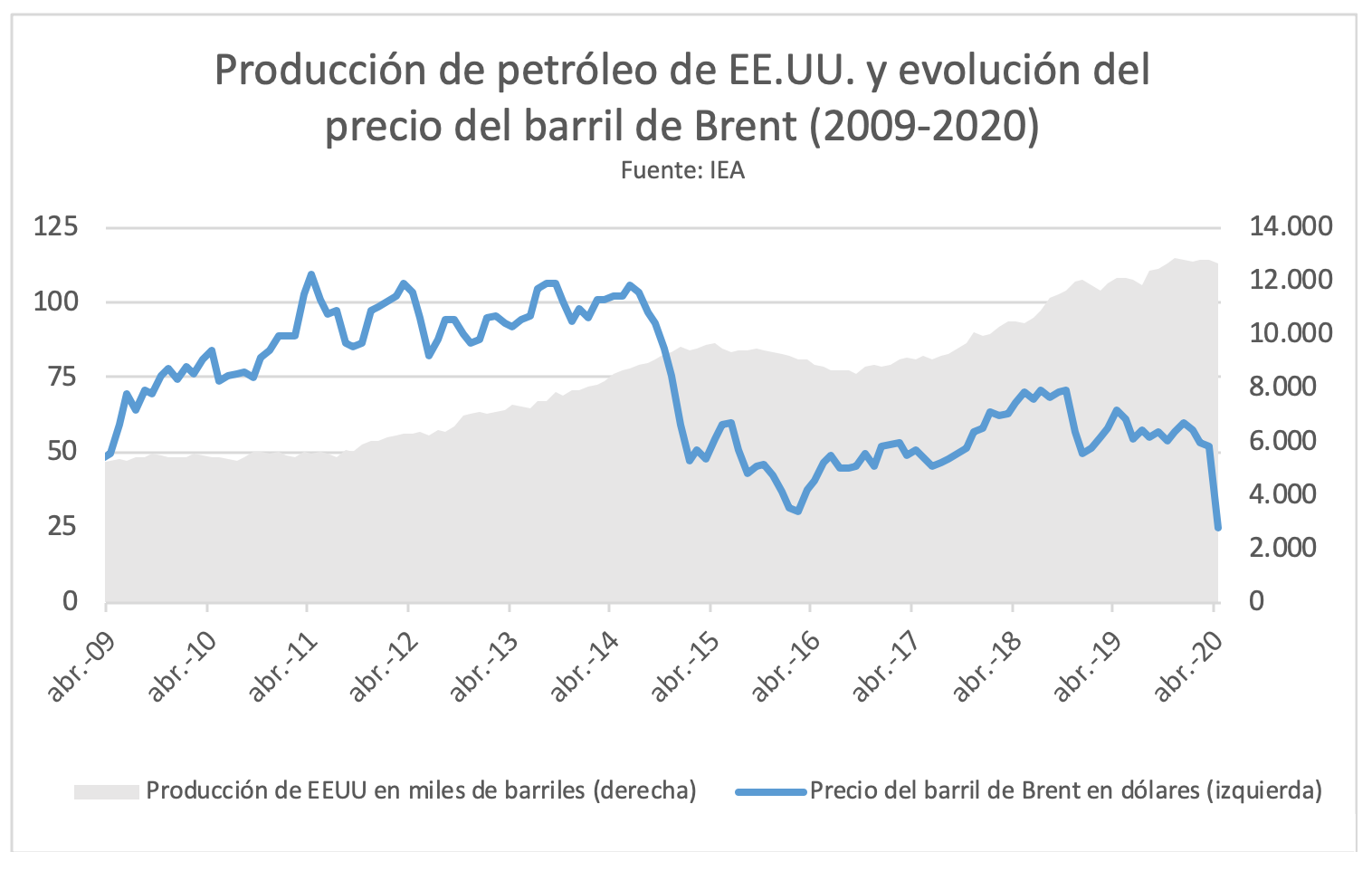

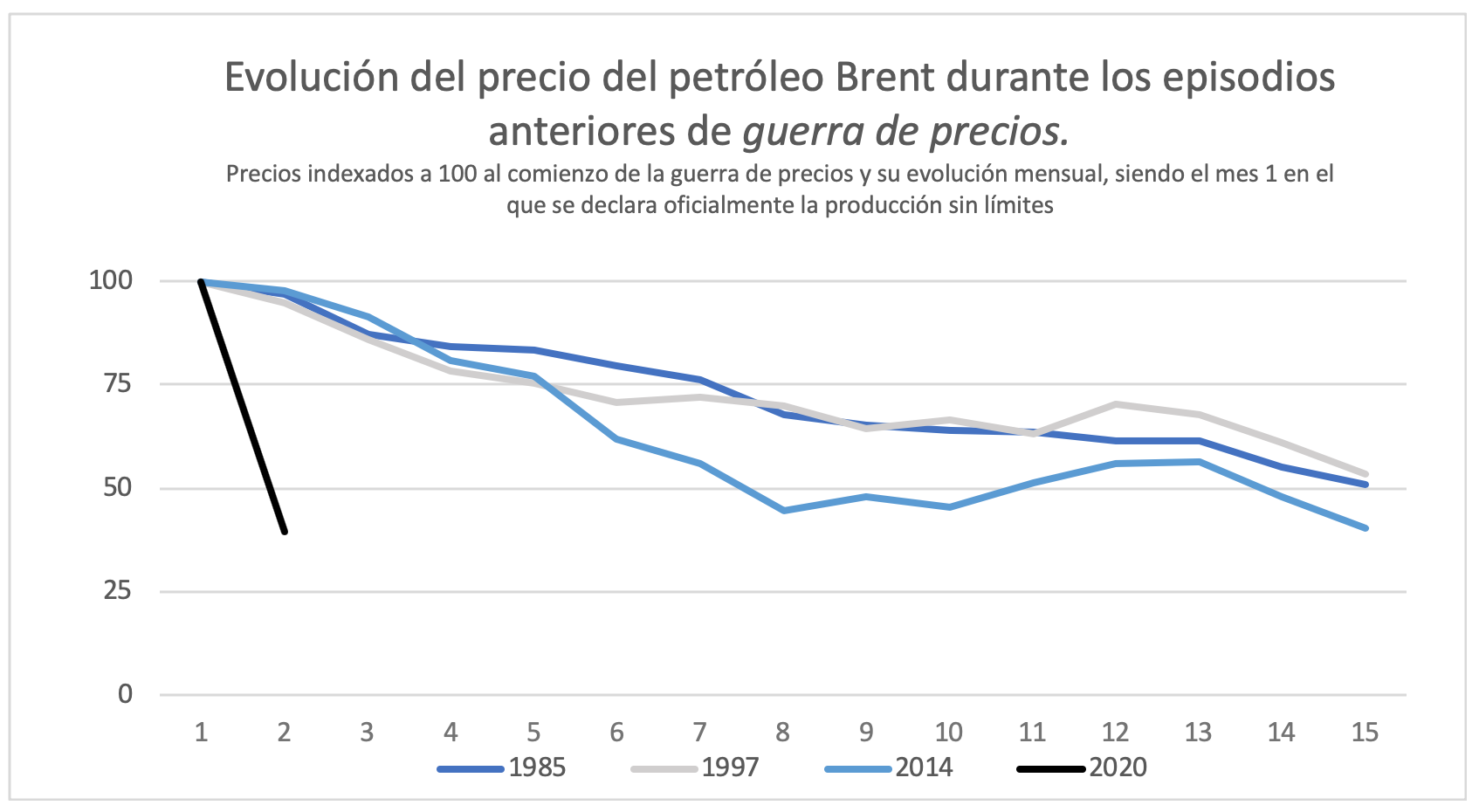

March and April 2020 will be remembered in the oil industry as the months in which the perfect storm occurred: a drop of more than 20% in world demand at the same time as a price war was unleashed that increased the supply of crude oil, generating an unprecedented status of abundance. This status has highlighted the end of OPEC's dominance over the rest of the oil producers and consumers after almost half a century.

![Pumping structure in a shale oil field [Pixabay]. Pumping structure in a shale oil field [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/precio-petroleo-blog.jpg)

▲ Pumping structure in a shale oil field [Pixabay].

ANALYSIS / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa

On 8 March, in view of the failure of the so-called group OPEC+ negotiations, Saudi Arabia offered its crude oil at a discount of between 6 and 8 dollars on the international market while announcing an increase in production from 1 April to a record 12 million barrels per day. The Saudi move was imitated by other producers such as Russia, which announced an increase of 500,000 barrels per day (bpd) from the same date, when the cartel's previous agreements expire. The reaction of the markets was immediate, with a historic drop in prices of more than 30% in all international indices and the opening of headlines announcing the start of a new price war. The oil world was stunned by the collapse in the price of crude oil, which reached historic lows on 30 March, with the price of a barrel of WTI dropping below 20 dollars, a psychological barrier that demonstrated the harshness of the confrontation and the historic consequences it could have for a sector of particular geopolitical sensitivity.

Previous experiences

Saudi Arabia, the world leader in the oil industry because of its vast reserves and huge, export-oriented production, has resorted three times to a price war to obtain commitments from other producers to make supply cuts to stabilise international prices. The oil market, accustomed to an artificially high price, tends to suffer dramatic price declines when supply is unrestricted available . committee Due to the economic and political instability that these prices generate in the producing countries, they usually return quickly to the negotiating table, where Saudi Arabia and its partners in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) always await them.

The first experience of this subject took place in 1985, after the Iran-Iraq war and the oil crisis of the 1970s, Saudi King Fahd bin Abdulaziz Al Saud took the decision to increase production unilaterally in order to recover the market share he had lost to the emergence of new producing regions such as the North Sea or the Gulf of Mexico. The experience led to a 50% drop in prices after more than a year of unrestricted production, which ended with a agreement in December 1986 by 12 OPEC countries to make the cuts demanded by Saudi Arabia and its allies.

In 1997, in response to Saudi Arabia's concern over the increasing displacement of its oil from US refineries in favour of Venezuelan and Mexican crude, the newly arrived Saudi monarch Abdullah bin Abdulaziz decided to announce in the midst of an OPEC summit in Jakarta that he would proceed to increase production without restrictions. The Saudi strategy did not count on the fact that the following year an economic crisis would break out among emerging markets with particular virulence in Southeast Asia and Russia, which plunged prices by 50% again until a new agreement was reached in April 1999.

With the 21st century, came the oil bonanza with the so-called commodity super cycle (2000-2014) that kept oil prices at unknown levels above 100 dollars between 2008 and 2010-2014. This bonanza made it possible to increase investment in exploration and production, generating new extraction techniques that were previously unknown or simply economically unfeasible. In 2005, the US was experiencing a worrying oil crisis, with production at an all-time low of only 5.2 million bpd compared to 9.6 million bpd in 1970. Moreover, energy dependence of approximately 6 million bpd was being met by increasingly expensive crude oil imports from the Persian Gulf, which after 9/11 was viewed with greater scepticism, and Venezuela, which already had Hugo Chávez as its political leader. goal High oil prices allowed the recovery of previously frustrated ideas such as hydraulic fracturing, which was given massive permits to be developed from 2005 onwards with the aim of mitigating the country's other major energy crisis: the rapid decline in domestic production of natural gas, a much more expensive and difficult commodity for the US to import. Hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, enabled an unexpected growth in natural gas production, which soon attracted the attention of the US oil sector. By 2008, a variant of fracking could be applied to oil extraction, a technique later called shale, leading to an unprecedented revolution in the United States that increased the country's production by more than 5 million barrels per day in the period 2008-2014. The change in the US energy landscape was such that in 2015 Barack Obama withdrew a 1975 law that prohibited the US from exporting domestically produced oil.