Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Analysis .

ANALYSIS / Salvador Sánchez Tapia [Brigadier General (Res.)].

The COVID-19 pandemic that Spain has been experiencing since the beginning of 2020 has brought to light the commonplace, no less true for having been repeated, that the concept of national security can no longer be limited to the narrow framework of military defence and demands the involvement of all the nation's capabilities, coordinated at the highest possible level which, in Spain's case, is none other than that of the Presidency of the Government through the National Security committee .[1]

Consistent with this approach, our Armed Forces have been directly and actively involved in a health emergency that is a priori far removed from the traditional missions of the nation's military arm. This military contribution, however, responds to one of the missions entrusted to the Armed Forces by the Organic Law of National Defence, in addition to a long tradition of military support to civil society in the event of catastrophes or emergencies. [2] In its execution, units of the three armies have carried out tasks as varied and apparently unrelated to their natural activity as the disinfection of old people's homes or the transfer of corpses between hospitals and morgues.

This status has stirred up a certain discussion in specialised and professional circles about the role of the armed forces in present and future security scenarios. From different angles, some voices are calling for the need to reconsider the missions and dimensions of armies in order to align them with these new threats, not with the classic war between states.

internship This view seems to be supported by the apparently empirical observation of the current absence of conventional armed conflicts - understood as those that pit armies with conventional means against each other manoeuvring on a battlefield - between states. Based on this reality, it is concluded that this form of conflict is practically banished, being little more than a historical relic replaced by other less conventional and less "military" threats such as pandemics, terrorism, organised crime, fake news, disinformation, climate change or cyber threats.

The corollary is obvious: it is necessary and urgent to rethink the missions, dimensions and equipment of the Armed Forces, as their current configuration is designed to confront outdated conventional threats, and not for those that are emerging in the present and future security scenario.

A critical analysis of this idea sample, however, paints a somewhat more nuanced picture. From a purely chronological point of view, the still unfinished Syrian civil war, admittedly complex, is closer to a conventional model than to any other subject and, of course, the capabilities with which Russia is making its influence felt in this war by supporting the Assad regime are fully conventional. In 2008, Russia invaded Georgia and occupied South Ossetia and Abkhazia in a conventional offensive operation. In 2006, Israel faced a hybrid enemy in South Lebanon in the form of Hezbollah - indeed, this was the model chosen by Hoffman as the prototype for the term "hybrid" - which combined elements of irregular warfare with fully conventional ones. [3] Earlier still, in 2003, the US invaded Iraq in a massive armoured offensive.[4]

If the case of Syria is eliminated as doubtfully classifiable as conventional warfare, it can still be argued that the last conflict of this nature - which, moreover, involved territorial gain - took place only twelve years ago; a short enough period of time to think that conclusions can be drawn that conventional warfare can be dismissed as a quasi-extinct procedure . In fact, the past has recorded longer periods than this without significant confrontation, which might well have led to similar conclusions. In Imperial Roman times, for example, the Antonine era (96-192 AD), saw a long period of internal Pax Romana briefly disrupted by Trajan's campaigns in Dacia. More recently, after Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo (1815), the Central Powers of Europe experienced a long period of peace lasting no less than thirty-nine years. [5] Needless to say, the end of both periods was marked by the return of war to the foreground.

It can be argued that status is now different, as humanity today has developed a moral rejection of war as a destructive and therefore unethical and undesirable exercise. This distinctly Western-centric - or, if you prefer, Eurocentric - stance takes the part for the whole and assumes this view to be unanimously shared globally. However, the experience of the Old Continent, with a long history of destructive wars between its states, a highly ageing population, and little appetite to remain a relevant player in the international system, may not be shared by everyone.

Western rejection of war may, moreover, be more apparent than real, being directly related to the interests at stake. It is conceivable that, faced with an immediate threat to its survival, any European state would be willing to go to war, even at the risk of becoming a pariah ostracised by the international system. If, at that point, such a state had sacrificed its traditional military muscle in favour of fighting more ethereal threats, it would have to pay the price associated with such a decision. Bear in mind that states choose their wars only up to a point, and may be forced into them, even against their will. As Trotsky said, "you may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you".

The analysis of the historical periods of peace referred to above suggests that, in both cases, they were made possible by the existence of a power moderator stronger than that of the political entities that made up the Roman Empire and post-Napoleonic Europe. In the first case, this power would have been that of Rome itself and its legions, sufficient to guarantee the internal order of the empire. In the second, the European powers, at odds for many reasons, nevertheless stood united against France in the face of the possibility that the ideas of the French Revolution would spread and undermine the foundations of the Ancien Régime.

Today, although it is difficult to find a verifiable cause-effect relationship, it is plausible to think that this "pacifying" force is provided by American military power and the existence of nuclear weapons. Since the end of World War II, the United States has provided an effective security umbrella under whose protection Europe and other regions of the world have been spared the scourge of war on their territories, developing feelings of extreme rejection of any form of war.

On the basis of its unrivalled military might, the United States - and we with it - have been able to develop the idea, supported by the facts, that no other power will be so suicidal as to engage in open conventional warfare. The conclusion is clear: conventional war - against the United States, I might add - is, at internship, unthinkable.

This conclusion, however, is not based on a moral preference, nor on the conviction that other forms of warfare or threat are more effective, but simply on the realisation that, faced with America's enormous conventional power, one can only seek asymmetry and confront it by other means. To paraphrase Conrad Crane, "there are two kinds of enemy: the asymmetrical and the stupid".[6]

In other words, classical military power is a major deterrent that financial aid helps explain the leave recurrence of conventional warfare. Not surprisingly, even authors who preach the end of conventional war advocate that the United States should retain its conventional warfare capability.[7]

From North America, this idea has permeated the rest of the world, or at least the European cultural sphere, where it has become a truism that, under the guise of incontestable reality, obviates the possibility of a conventional war being initiated by the United States - as happened in 2003 - or between two nations of the world, or within one of them, in areas where armed conflict continues to be acceptable tool .

In an exercise in cynicism, one might say that such a possibility does not change anything, because it is none of our business. However, in today's interconnected world, there will always be the possibility that we will be forced to intervene for ethical reasons, or that our security interests will be affected by events in countries or regions a priori geographically and geopolitically distant from us, and that, probably hand in hand with our allies, we will be involved in a classic war.

While still in place, the commitment of US military power to Western security is under severe strain as America is increasingly reluctant to take on this role alone, and demands that its partners do more for its own security. We are not suggesting here that the transatlantic link will break down immediately. It seems sensible, however, to think that maintaining it comes at a cost to us that could drag us into armed conflict. It is also worth asking what might happen if one day the US commitment to our security were to lapse and we had transformed our armed forces to focus exclusively on the "new threats", dispensing with a conventional capability that would undoubtedly lower the cost that someone would have to incur if they decided to attack us with such means subject .

A final consideration has to do with what appears to be China's unstoppable rise to the role of major player in the International System, and with the presence of an increasingly assertive Russia, which is demanding to be considered a major global power once again. Both nations, especially the former, are clearly undergoing a process of rearmament and modernisation of their military, conventional and nuclear capabilities that does not exactly augur the end of conventional warfare between states.

To this must be added the effects of the pandemic, which are still difficult to glimpse, but among which there are some worrying aspects that should not be overlooked. One of these is China's effort to position itself as the real winner of the crisis, and as the international power of reference letter in the event of a repeat of the current global crisis. Another is the possibility that the crisis will result, at least temporarily, in less international cooperation, not more; that we will witness a certain regression of globalisation; and that we will see the erection of barriers to the movement of people and goods in what would be a reinforcement of realist logic as a regulatory element of International Office.

In these circumstances, it is difficult to predict the future evolution of the "Thucydides trap" in which we currently find ourselves as a result of China's rise. It is likely, however, to bring with it greater instability, with the possibility of escalation into a conventional subject conflict, whether between great powers or through proxies. In such circumstances, it seems advisable to be prepared for the most dangerous scenario of open armed conflict with China to materialise, as the best way to avoid it, or at least to deal with it in order to preserve our way of life and our values.

Finally, one cannot overlook the capacity of many of the "new threats" - global warming, pandemics, etc. - to generate or at least catalyse conflicts, which can indeed lead to a war that could well be conventional.

From all of the above it can be concluded, therefore, that if it is true that the recurrence of conventional warfare between states is minimal nowadays, it seems risky to think that it might be put away in some obscure attic, as if it were an ancient relic. However remote the possibility may seem, no one is in a position to guarantee that the future will not bring conventional war. Neglecting the ability to defend against it is therefore not a prudent option, especially given that, if needed, it cannot be improvised.

The emergence of new threats such as those referred to in this article, perhaps more pressing, and many of them non-military or at least not purely military, is undeniable, as is the need for the Armed Forces to consider them and adapt to them, not only to maximise the effectiveness of their contribution to the nation's effort against them, but also as a simple matter of self-protection.

In our opinion, this adaptation does not entail abandoning conventional missions, the true raison d'être of the Armed Forces, but rather incorporating as many new elements as necessary, and ensuring that the armies fit into the coordinated effort of the nation, contributing to it with the means at their disposal, considering that, in many cases, they will not be the first response element, but rather a support element.

This article does not argue - it is not its goal- either for or against the need for Spain to rethink the organisation, size and equipment of its armed forces in light of the new security scenario. Nor does it enter into the question of whether it should do so unilaterally, or at agreement with its NATO allies, or by seeking complementarity and synergy with its European Union partners. Understanding that it is up to citizens to decide what armed forces they want, what they want them for, and what effort in resources they are willing to invest in them, what this article postulates is that national security is best served if those who have to decide, and with them the armed forces, continue to consider conventional warfare, enriched with a multitude of new possibilities, as one of the possible threats the nation may have to face. Redefining the adage: Si vis pacem, para bellum etiam magis.[8]

[1] Law 36/2015, on National Security.

agreement [2] According to article 15. 3 of Organic Law 5/2005 on National Defence, "The Armed Forces, together with the State Institutions and Public Administrations, must preserve the security and well-being of citizens in cases of serious risk, catastrophe, calamity or other public needs, in accordance with the provisions of current legislation". These tasks are often referred to as "support to civil society". This work consciously avoids using that terminology, as it obviates that this is what the Armed Forces always do, even when fighting in an armed conflict. It is more correct to add the qualifier "in the event of a disaster or emergency".

[3] Frank G. Hoffman. Conflict in the 21st Century; The Rise of Hybrid Wars, Arlington, VA: Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 2007. On the conventional aspect of Israel's 2006 war in Lebanon see, for example, 34 Days. Israel, Hezbollah, and the War in Lebanon, London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009.

[4] Saddam's response contained a significant irregular element but, by design, relied on the Republican National Guard Divisions, which offered weak armoured and mechanised resistance.

[5] Azar Gat, War in Human Civilization, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 536. This calculation excludes peripheral Spain and Italy, which did experience periods of war in this period.

[6] Dr. Conrad C. Crane is . Crane is Director of the Historical Services of the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and principal author of the celebrated "Field guide 3-24/Marine Corps Warfighting Publication 3-33.5, Counterinsurgency. "

[7] Jahara Matisek and Ian Bertram, "The Death of American Conventional Warfare," Real Clear Defense, November 6th, 2017. (accessed May 28, 2020).

[8] "If you want peace, prepare even more for war".

March and April 2020 will be remembered in the oil industry as the months in which the perfect storm occurred: a drop of more than 20% in world demand at the same time as a price war was unleashed that increased the supply of crude oil, generating an unprecedented status of abundance. This status has highlighted the end of OPEC's dominance over the rest of the oil producers and consumers after almost half a century.

![Pumping structure in a shale oil field [Pixabay]. Pumping structure in a shale oil field [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/precio-petroleo-blog.jpg)

▲ Pumping structure in a shale oil field [Pixabay].

ANALYSIS / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa

On 8 March, in view of the failure of the so-called group OPEC+ negotiations, Saudi Arabia offered its crude oil at a discount of between 6 and 8 dollars on the international market while announcing an increase in production from 1 April to a record 12 million barrels per day. The Saudi move was imitated by other producers such as Russia, which announced an increase of 500,000 barrels per day (bpd) from the same date, when the cartel's previous agreements expire. The reaction of the markets was immediate, with a historic drop in prices of more than 30% in all international indices and the opening of headlines announcing the start of a new price war. The oil world was stunned by the collapse in the price of crude oil, which reached historic lows on 30 March, with the price of a barrel of WTI dropping below 20 dollars, a psychological barrier that demonstrated the harshness of the confrontation and the historic consequences it could have for a sector of particular geopolitical sensitivity.

Previous experiences

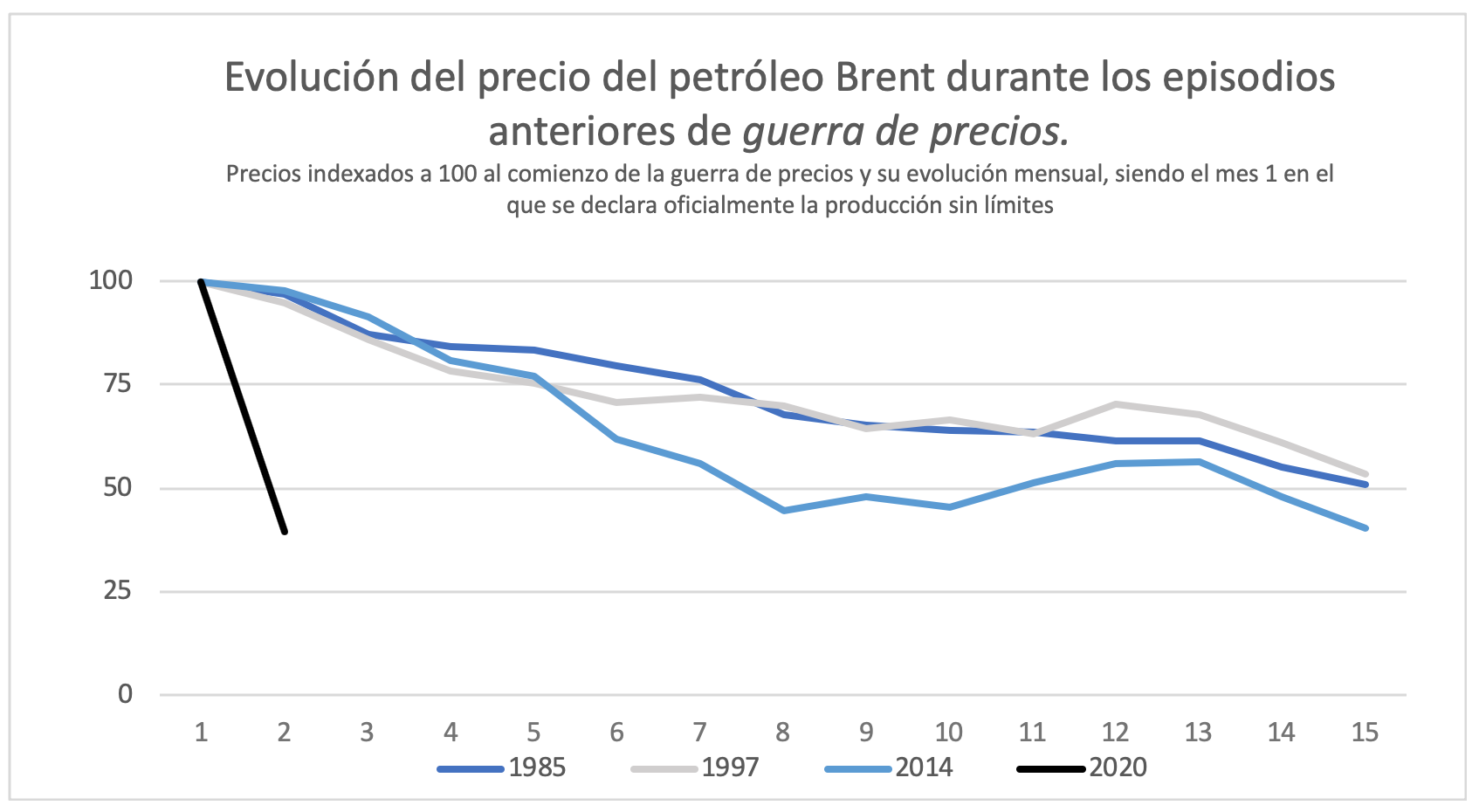

Saudi Arabia, the world leader in the oil industry because of its vast reserves and huge, export-oriented production, has resorted three times to a price war to obtain commitments from other producers to make supply cuts to stabilise international prices. The oil market, accustomed to an artificially high price, tends to suffer dramatic price declines when supply is unrestricted available . committee Due to the economic and political instability that these prices generate in the producing countries, they usually return quickly to the negotiating table, where Saudi Arabia and its partners in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) always await them.

The first experience of this subject took place in 1985, after the Iran-Iraq war and the oil crisis of the 1970s, Saudi King Fahd bin Abdulaziz Al Saud took the decision to increase production unilaterally in order to recover the market share he had lost to the emergence of new producing regions such as the North Sea or the Gulf of Mexico. The experience led to a 50% drop in prices after more than a year of unrestricted production, which ended with a agreement in December 1986 by 12 OPEC countries to make the cuts demanded by Saudi Arabia and its allies.

In 1997, in response to Saudi Arabia's concern over the increasing displacement of its oil from US refineries in favour of Venezuelan and Mexican crude, the newly arrived Saudi monarch Abdullah bin Abdulaziz decided to announce in the midst of an OPEC summit in Jakarta that he would proceed to increase production without restrictions. The Saudi strategy did not count on the fact that the following year an economic crisis would break out among emerging markets with particular virulence in Southeast Asia and Russia, which plunged prices by 50% again until a new agreement was reached in April 1999.

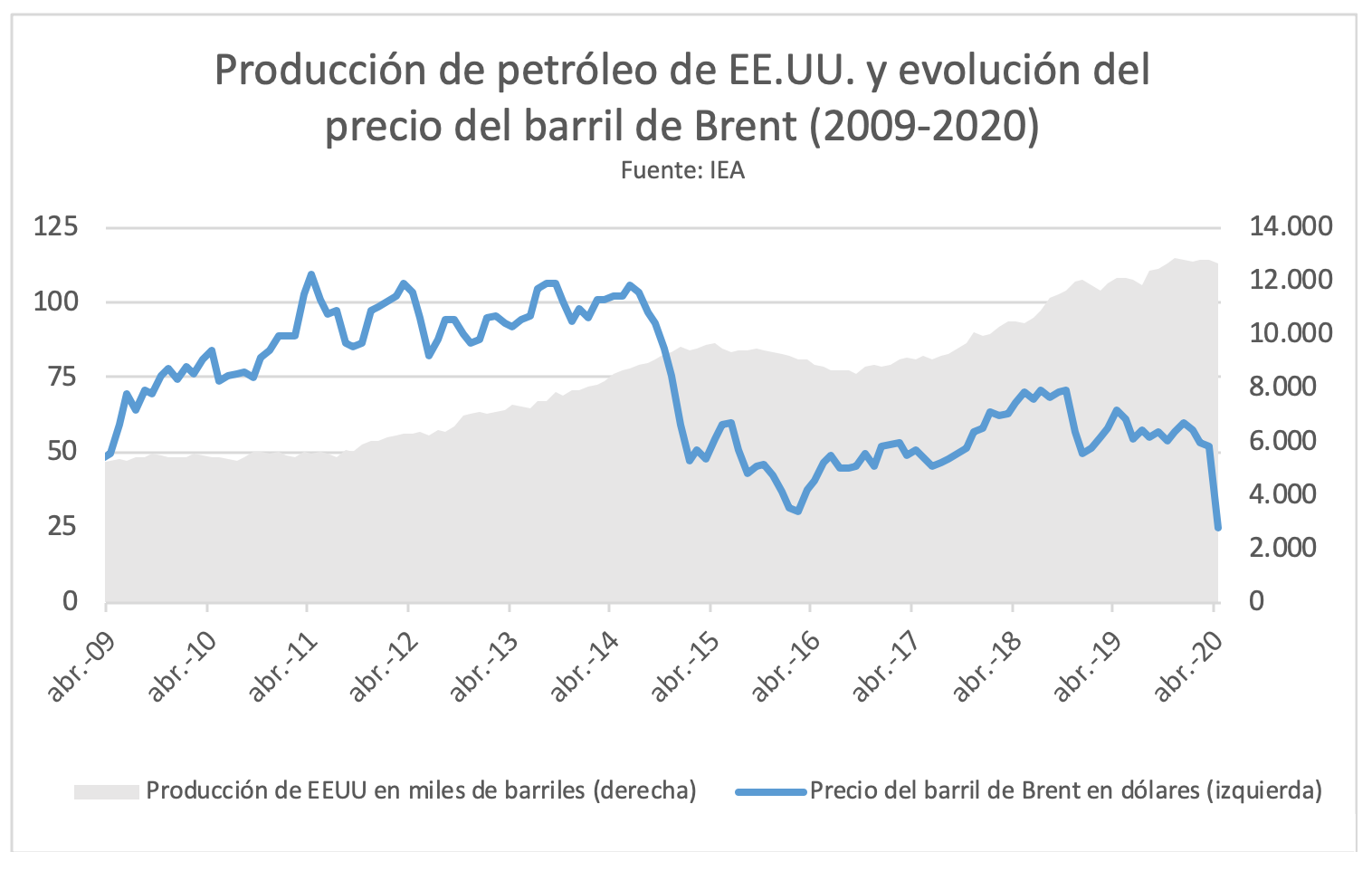

With the 21st century, came the oil bonanza with the so-called commodity super cycle (2000-2014) that kept oil prices at unknown levels above 100 dollars between 2008 and 2010-2014. This bonanza made it possible to increase investment in exploration and production, generating new extraction techniques that were previously unknown or simply economically unfeasible. In 2005, the US was experiencing a worrying oil crisis, with production at an all-time low of only 5.2 million bpd compared to 9.6 million bpd in 1970. Moreover, energy dependence of approximately 6 million bpd was being met by increasingly expensive crude oil imports from the Persian Gulf, which after 9/11 was viewed with greater scepticism, and Venezuela, which already had Hugo Chávez as its political leader. goal High oil prices allowed the recovery of previously frustrated ideas such as hydraulic fracturing, which was given massive permits to be developed from 2005 onwards with the aim of mitigating the country's other major energy crisis: the rapid decline in domestic production of natural gas, a much more expensive and difficult commodity for the US to import. Hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, enabled an unexpected growth in natural gas production, which soon attracted the attention of the US oil sector. By 2008, a variant of fracking could be applied to oil extraction, a technique later called shale, leading to an unprecedented revolution in the United States that increased the country's production by more than 5 million barrels per day in the period 2008-2014. The change in the US energy landscape was such that in 2015 Barack Obama withdrew a 1975 law that prohibited the US from exporting domestically produced oil.

The Saudi reaction was swift, and at OPEC's Vienna headquarters in November 2014, it launched a new campaign of unrestricted production that would allow the Kingdom to recover part of its market share. The effects on international markets were more dramatic than ever, with a 50% drop in price in just 7 months. Multinational oil companies (IOCs) and national oil companies (NOCs) dramatically reduced their profits and were forced to make cuts not seen since the beginning of the century. Exporting countries also suffered the effects of lower fiscal revenues with many emerging markets plunged into unmanageable fiscal deficits, inflation and even recession, with Venezuela in particular sliding into the socio-economic chaos we know today. To Saudi Arabia's despair, the US shale industry showed unexpected resilience by maintaining production at 4 million barrels per day for 2016 from a peak of 5 million in 2014. Saudi Arabia did not understand that shale oil, unlike conventional oil, was not a mature industry, but an expanding one and development. US producers managed to increase the oil recovery rate from 5% to 12% between 2008-2016, the equivalent of increasing productivity by 2.4 times. In addition, the elimination of less competitive companies allowed for a reduction in the cost of services and easier access to transportation infrastructure. The nature of shale, with wells maturing in 18 months to 3 years, compared to 30 years or more for a conventional well, allowed production to be shut in for a short enough period of time to minimise the impact of lower prices, opting to keep the most competitive wells. Saudi Arabia gave up and opted for a 180 degree turnaround Degrees in its strategy, although it did manage to bring Russia to the negotiating table. The longest price war in history, after almost 22 months, ended with an unprecedented agreement among OPEC countries with the incorporation of Russia and its sphere of energy influence, group known as OPEC+. A Russia wounded by international sanctions and the weakness of its currency had given in to Saudi Arabia, which, however, had not managed to defeat the US shale oil revolution.

North American shale production has not stopped growing, and despite its effectiveness, it is the only region in the world with a similar industry, growing at a rate of more than one million barrels per day per year. This status has provided the US with robust energy security as it is not dependent on imports of Venezuelan or Gulf crude. The country achieved positive net oil exports at the end of 2019 for the first time in more than half a century, in addition to being a net exporter of natural gas, coal and refined products. Much of the Trump administration's geostrategic retreat in the Middle East is a response to the country's growing energy independence, which reduces its interests in the region.

The breakdown of group OPEC+:

As mentioned, during the first week of March, OPEC+ met in Vienna seeking a agreement for a further cut of some 1.8 million barrels per day to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in China. The unease among producers was evident, having executed a similar cut in December 2019. Saudi Arabia was trying to share out as much of the production cuts as possible when Russian energy minister Alexander Novak said "niet", citing economic solvency for a drop in prices, scuppering any subject from agreement. It is not known whether Russia's refusal was the result of a well-thought-out plan or simply a bluff to gain ground in the negotiations, but it was the beginning of a new price war. As can be seen in the graph below, the drop in the price of crude oil in the first month has been historic, without a similar reference letter in the history of negotiations between producers. The increase in the availability of oil in the markets due to the Saudi strategy of loading tankers with crude from its strategic reserves, together with a dry stop of the Economics and the demand for oil, generated a sudden price depression hitherto unknown in the sector. Previous price wars normally had the stabilising element that the lower the price of oil products, the higher the consumption in the short term deadline. However, due to the economic effects of the quarantine, this market counterweight disappears, generating in one month what would otherwise have taken 12 to 15 months.

The effects of COVID-19 on global oil demand are estimated to have fallen by 12.5% in March and are expected to reach 20% in April. In the areas of Europe most affected by the quarantine, the drop in fuel sales at service stations has reached 75%, a figure that is very likely to be replicated in the rest of the advanced economies as the measures are tightened and which China is already beginning to leave behind after two months of confinement. The case of air transport is particular, as it consumes 16 million bpd and is currently totally suspended, with no clear date for a return to normality in international aviation. The partial stoppage of industrial production, the extent of which is still unknown, could lead to even greater drops in consumption. Such a status would not require increased production to generate a collapse in prices, which with the added pressure on the supply side are generating unprecedented levels of stress on storage, transport and refining capacity.

A historic agreement :

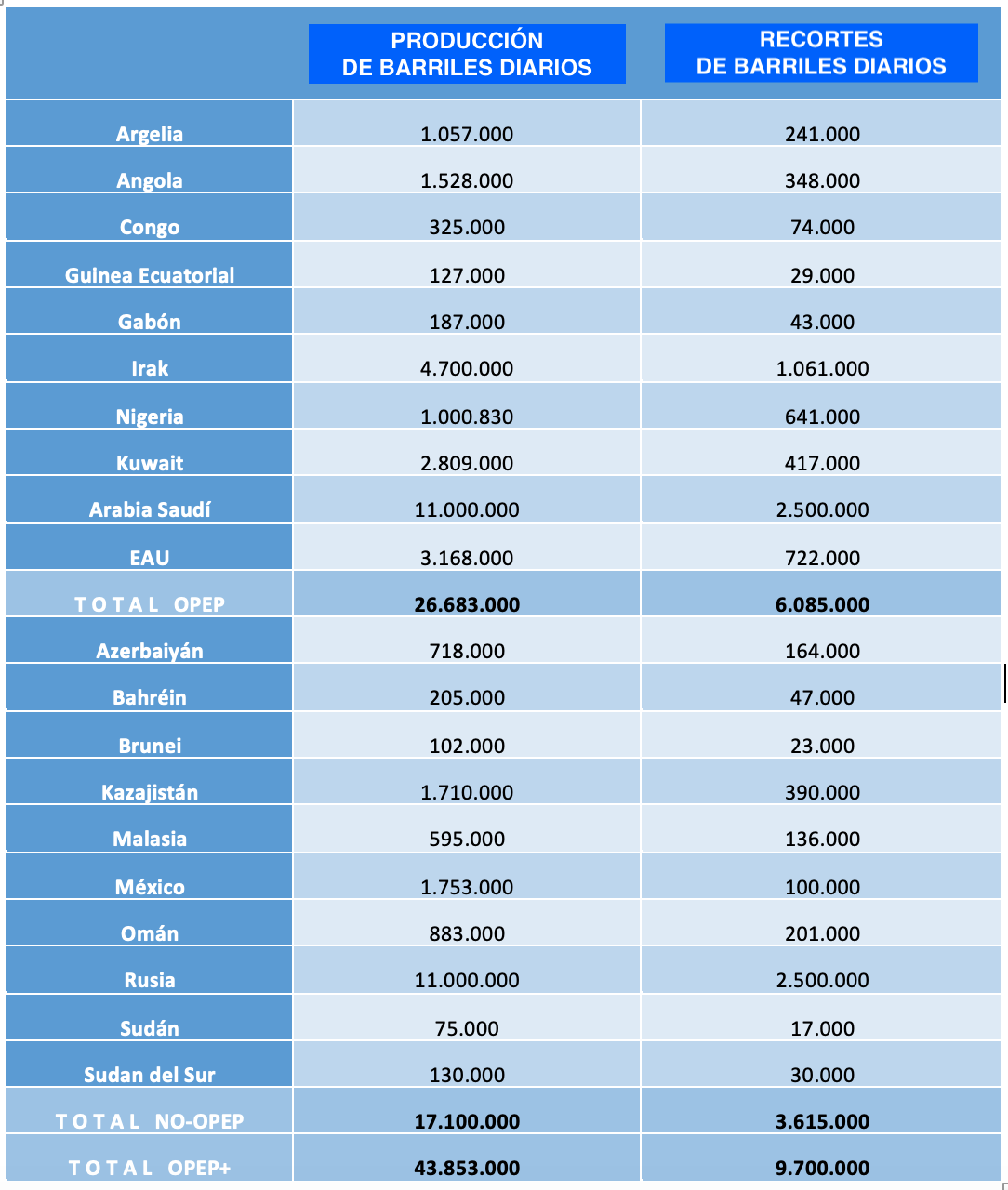

In early April, Donald Trump, fearful that an oil glut could further depress prices and destroy the US hydrocarbon industry, took the initiative to speak by telephone with the leaders of Saudi Arabia and Russia. In a paradoxical move, the US President succeeded in bringing the major producers closer together to establish new cuts that would put an end to the price war. On 9 April, after several weeks of speculation, the largest ever producers' meeting took place at group , including OPEC members and 10 non-member countries among which Russia, Kazakhstan and Mexico stood out. After several days of negotiations, it was agreed to cut production by 23% in 20 countries with a combined output of more than 40 million barrels, leaving almost 10 million barrels out of the market, starting on the first day of May. The negotiations were coordinated by OPEC and the G20, which at the time was chaired by Saudi Arabia. In this way, a picturesque agreement was reached whereby the aforementioned 10 million barrels were reduced among the OPEC+ members, included in the table below, and another 5 million barrels were estimated to be reduced in an unspecified manner among the US, Canada, Brazil and Norway. The latter cuts, by the nature of their sectors, would be made through the free market and it remains to be seen how they will materialise.

There is some scepticism in the industry and markets about the effectiveness of these cuts, which amount to 10-15% of the oil consumed globally before the COVID-19 crisis. Consumption has fallen by around 20% and oil storage capacity is starting to run out, reducing the margin for absorbing surplus oil. In addition, the cuts will start to be implemented on 1 May, leaving a three-week window that could further depress prices. The nature of agreement, which is voluntary and difficult to monitor, leaves the door open to non-compliance with the established cuts, which are often difficult to apply due to the geological conditions of certain old wells or the existence of contracts that require financial compensation if supply is interrupted. In general, the level of compliance with OPEC agreements has been low, with a greater incidence in countries that export by sea and a lesser incidence in those that export by pipeline, which, unlike maritime cargoes, cannot be controlled by satellite.

The main actors:

Saudi Arabia:

Amid the wreckage of the OPEC+ negotiations, on 6 March Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) led a new palace coup in which former heir to the Saudi throne Mohammed bin Nayef and other members of the royal family were arrested and charged with plotting against Crown Prince MBS and his father Salman bin Abdulaziz. All this at a time when the heir to the Saudi throne seemed to want to consolidate his power with a risky new strategy after the utter failure of the Yemen War and the Vision 2030 national modernisation plan.

Saudi Arabia's undisputed leadership in driving the oil market is based on its ability to increase production by several million barrels in less than six months, something no other country in the world is able to do. The increase in production also allows Saudi Arabia to partially compensate for the decline in prices per barrel, which together with its foreign exchange reserves and access to cheap credit allows Saudi Arabia to face a price war with an apparent resilience far superior to that of any other OPEC country. The low cost of producing a barrel of oil in the country, at around $7, also allows it to maintain revenues in almost any market environment.

However, foreign exchange reserves, at $500 billion, are 30% lower than in 2016, and may be insufficient to maintain dollar-rial parity for more than two years without oil revenues, which is essential for a society accustomed to import-dependent opulence. Moreover, the fiscal deficit has been a major problem for the country, which has been unable to reduce it below 4% after reaching a peak of 16% in 2016 as result of an insufficient recovery in oil prices and the costs of the war in Yemen. Oil's energy dominance has an expiry date and Saudi Arabia's finances are addicted to an activity that accounts for 42% of its GDP and generates 87% of tax revenues. For the moment, the Saudi minister of Economics has already announced a 5% cut in budget by 2020, sample , agreement oil does not ensure an optimistic scenario. In any case, Saudi Arabia has been one of the big winners in the price war. In the failed March negotiations, Saudi Arabia produced 9.7 million barrels per day, a figure that had risen to 11 million barrels per day in the April negotiations. As the cuts are set on a proportional basis, in just one month the Saudi kingdom gained 1.3 million barrels of market share. Similarly, the Saudi sovereign wealth fund Petroleum Investment Fund (PIF) bought shares in Eni, Total, Equinor, Shell and Repsol during the month of April, in a context of stock market falls in these companies.

Russian Federation:

Russia stood firm at the start of the price war, highlighting the resilience of the Russian energy sector and the volume of the country's sovereign reserves, which are lower than those of Saudi Arabia but amount to 435 billion dollars and a stabilisation fund of another 100 billion: 33% more than in 2014. Paradoxically, international sanctions on the Russian oil sector have reduced its dependence on the outside world, allowing the devaluation of the freely convertible rouble not to affect production and partially compensate for lower prices. Russia' s capacity to increase production in the short term deadline, unlike Saudi Arabia, is less than 500,000 bpd, which leaves Russia unable to compensate lower prices with higher production, the main reason for the country's acceptance of the April negotiations result .

Vladimir Putin's leadership is unquestionable with a possible constitutional reform that would allow for an extension of his term of office delayed due to COVID-19. The Russian political elite's good relations with the oil oligarchy allow for unity of action in a country with greater atomisation and the presence of private capital in its companies. Alexander Novak's strategy seems to be in line with that of Igor Sechin, CEO of Rosneft, who is betting on a context of low prices that will end up deeply damaging the US shale industry. There is speculation about a possible US diplomatic intervention with the Russian government in favour of April's agreement OPEC+. Russia's Rosneft's latest move , abandoning Venezuela by selling all its assets to a Russian government-controlled business , may be one explanation for Moscow's concession to accept a agreement that for a month it tried, at least rhetorically, to avoid. The development of future US sanctions on the Russian oil sector will be a good indicator of this possible agreement.

United States:

For the US, falling oil prices mean one of the biggest tax cuts of all time, in the words of its president, with a price of less than a dollar per gallon. However, the oil industry generates more than 10 million jobs in the US and is a central activity in many states such as Texas, Oklahoma or New Mexico, which are fundamental for a hypothetical Republican victory in the 2020 elections. Moreover, the geostrategic importance of the sector, which has allowed the US to reduce its energy dependence to historic lows, has led Donald Trump to take on the responsibility of safeguarding the US oil industry. He himself coordinated the first steps for a major agreement, by means of pressure, threats and concessions. The truth is that the price crisis has come at a time of certain exhaustion for the sector, which was beginning to suffer the effects of over-indebtedness and pressure from investors to increase profits. Since 2011, North American crude oil, priced on the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) index, has experienced an evaluation 10% lower than that of Brent or the OPEC Basket, the other global indices, generating a hyper-competitive environment that was beginning to take its toll on shale producers, which since the end of 2019 have seen a 20% drop in the total drillingissue year-on-year. The North American market, which had already been experiencing storage and transportation problems since 2017, collapsed in the third week of April with negative prices due to the limitations to store oil and speculation in the futures markets.

Donald Trump has finally secured a global agreement that does not bind the US directly, but leaves it to the market to regulate the cuts that seem more than foreseeable. In this way, the Trump administration allows itself not to have to intervene in the oil market, something that would surely force the development of legislation and a complex discussion to save the polluting oil industry at the taxpayer's expense. From the Senate, several politicians from both parties have tried to introduce the need for tariffs or sanctions on those producers who flood the domestic market to the parliamentary discussion , recovering old initiatives such as the NOPEC Act. These threats have allowed the President to gain a strong position at the international level, being one of the big winners at the agreement OPEC+ in April. In fact, when negotiations seemed on the verge of collapse due to Mexico's refusal to take on 400,000 barrels per day of cuts, the US intervened by announcing that it would be the US that would take them on. Subsequent leaks have shown the existence of financial insurance taken out by Mexico in case of low oil prices, which would be charged per barrel produced. The US intervention, more rhetorical than internship since the country has no concrete production to cut, saved agreement from another failure.

![Facilities for the refining of petroleum products [Pixabay]. Facilities for the refining of petroleum products [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/precio-petroleo-blog-2.jpg)

Facilities for the refining of petroleum products [Pixabay].

Nothing will ever be the same again:

The shale oil revolution has transformed the oil industry and generated a new geopolitical balance to the detriment of OPEC. Since 2016, OPEC+ countries have made cuts estimated at 5.3 million barrels per day, while the North American shale industry has increased its production by 4.2 million barrels, making it clear that the oligopolistic strategy of the producing countries has come to an end. All that remains is the free market, in which they have an advantage due to lower production costs. However, eliminating a large part of the North American shale final would take more than three years of prices below 30 dollars, at which point a large part of the companies' debt would mature and the drop in new wells issue would seriously affect total production. A journey in the desert for many producing countries that have billion-dollar plans for economic diversification during this decade, probably the last decade of absolute energy domination by hydrocarbons. The world, unlike what was expected at the beginning of the century, has entered a period of oil abundance that will reduce energy costs unless coordinated intervention in the market remedies this. The emergence of new producers, mainly the United States, Canada and Brazil, coupled with the collapse of Venezuelan and Libyan production, has left OPEC 's market share in 2020 at around 33%, in free fall since the beginning of the century when it exceeded 40%.

Global demand for crude oil has declined to such an extent that cutbacks can only be expected to prevent a fall below $15 a barrel by prolonging the full filling of remaining oil storage systems as long as possible. Global oil storage capacity is one of the great unknowns in the sector, with diverging estimates. The bulk of the storage capacity is supported by importing countries, which since the 1973 oil crisis decided to create the International Energy Agency, among other things, to coordinate infrastructure to mitigate dependence on OPEC. The strategic nature of these reserves, coupled with the rapid development of these reserves in the last decade by China and its companies, make access to this information very difficult. In particular, China's Sinopec has developed a strategy of building oil storage facilities throughout the China Sea, including in foreign countries such as Indonesia, to resist any possible blockade of the Strait of Malacca, China's geopolitical weak point. Private companies also have onshore and floating storage capacity of undetermined volume that has already begun to be used in imaginative ways: disused pipelines, oil tankers and even trains and trucks now grounded by quarantine. In the short term, deadline, these strategic reserves will be gradually replenished at a rate similar to 20 million barrels per day, an estimate of the current differential between supply and demand. In 50 days, if no agreement is reached to cut production, the amount in storage would exceed 1 billion barrels, which would probably saturate the market's capacity to absorb more oil, leading to a total collapse in prices.

A return to economic normality is increasingly on the distant horizon, with sectors such as aviation and tourism set to be weighed down by COVID-19 for a long time to come. The impact on oil demand will be prolonged, especially given the storage capacity that will now act as a counterweight to any upward movement in international prices. The shale industry, with great flexibility, will begin to hibernate while waiting for a new, more favourable context. The COVID-19 crisis will have a particularly virulent impact on the oil-exporting countries at development , which have more delicate socio-economic balances. The oil world is undergoing major changes as part of the energy transition and development of new technologies. The COVID-19 crisis is only the beginning of the major transformations that the industry will undergo in the coming decades. An oft-repeated phrase to refute the already dismissed Peak Oil theory is that the Stone Age did not end because of a lack of stones, and contemporary society will not stop using hydrocarbons because of their depletion, but because of their obsolescence.

The always difficult negotiations are made more difficult by the 75 billion euros the UK is giving up.

ANALYSIS / Pablo Gurbindo Palomo

The negotiations for the European budget for the period 2021-2027 are crucial for the future of the Union. After the failure of the extraordinary summit on 20-21 February, time is running out and the member states must put aside their differences in order to reach an agreement on agreement before 31 December 2020.

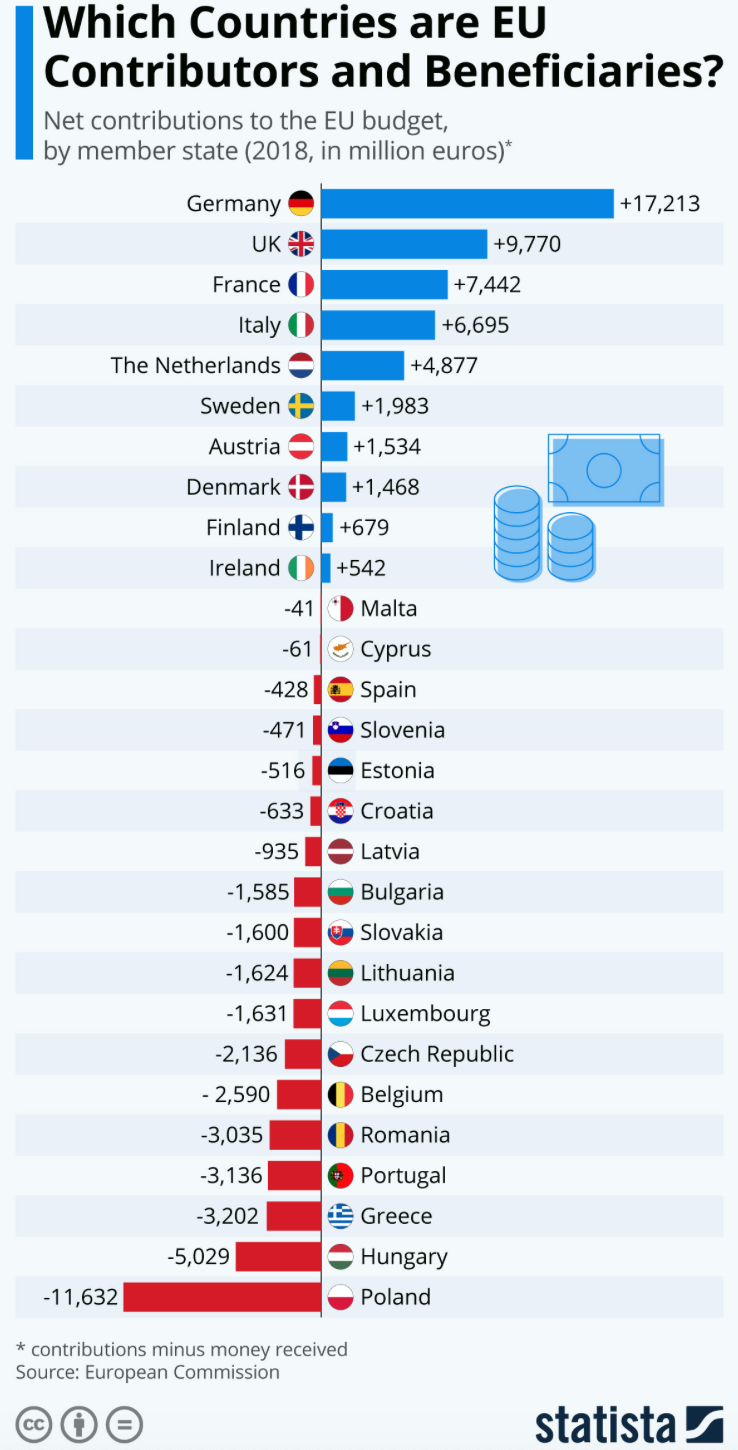

framework The negotiation of a new European Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) is always complicated and crucial, as the ambition of the Union depends on the amount of money that member states are willing to contribute. But the negotiation of this new budget line, for the period 2021-2027, has an added complication: it is the first without the United Kingdom after Brexit. This complication does not lie in the absence of the British in the negotiations (for some that is more of a relief) but in the 75 billion euros they have stopped contributing.

What is the MFP?

framework The Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF ) is the EU's long-term budgetary framework deadline and sets the limits for expense of the Union, both as a whole and in its different areas of activity, for a deadline period of no less than 5 years. In addition, the MFF includes a number of provisions and "special instruments" beyond that, so that even in unforeseen circumstances such as crises or emergencies, funds can be used to address the problem. This is why the MFF is crucial, as it sets the political priorities and objectives for the coming years.

This framework is initially proposed by the Commission and, on this basis, the committee (composed of all Member States) negotiates and has to come to a unanimous agreement . After this the proposal is sent to the European Parliament for approval.

The amount that goes to the MFF is calculated from the Gross National Income (GNI) of the Member States, i.e. the sum of the remuneration of the factors of production of all members. But customs duties, agricultural and sugar levies and other revenues such as VAT are also part of it.

Alliances for war

In the EU there are countries that are "net contributors" and others that are "net receivers". Some pay more to the Union than they receive in return, while others receive more than they contribute. This is why countries' positions are flawed when they face these negotiations: some want to pay less money and others do not want to receive less.

Like any self-respecting European war, alliances and coalitions have been formed beforehand.

The Commission 's proposal for the MFF 2021-2027 on 2 May 2018 already made many European capitals nervous. The proposal was 1.11 % of GNI (already excluding the UK). It envisaged budget increases for border control, defence, migration, internal and external security, cooperation with development and research, among other areas. On the other hand, cuts were foreseen in Cohesion Policy (aid to help the most disadvantaged regions of the Union) and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

The Parliament submitted a report provisional on this proposal in which it called for an increase to 1.3% of GNI (corresponding to a 16.7% increase from the previous proposal ). In addition, MEPs called, among other things, for cohesion and agriculture funding to be maintained as in the previous budget framework .

On 2 February 2019 the Finnish Presidency of committee proposed a negotiation framework starting at 1.07% of GNI.

This succession of events led to the emergence of two antagonistic blocs: the frugal club and the friends of cohesion.

The frugal club consists of four northern European countries: Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Austria. These countries are all net contributors and advocate a budget of no more than 1 % of GNI. On the other hand, they call for cuts to be made in what they consider to be "outdated" areas such as cohesion funds or the CAP, and want to increase the budget in other areas such as research and development, defence and the fight against immigration or climate change.

Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz has already announced that he will veto on committee any proposal that exceeds 1 % of GNI.

The Friends of Cohesion comprise fifteen countries from the south and east of the Union: Spain, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. All these countries are net recipients and demand that CAP and cohesion policy funding be maintained, and that the EU's budget be based on between 1.16 and 1.3 % of GNI.

This large group met on 1 February in the Portuguese town of Beja. There they tried to show an image of unity ahead of the first days of the MFP's discussion , which would take place in Brussels on the 20th and 21st of the same month. They also announced that they would block any subject cuts.

It will be curious to see whether, as the negotiations progress, the blocs will remain strong or whether each country will pull in its own direction.

Outside of these two groups, the two big net contributors stand out, pulling the strings of what happens in the EU: Germany and France.

Germany is closer to the frugals in wanting a more austere budget and more money for more modern items such as digitalisation or the fight against climate change. But first and foremost it wants a quick agreement .

France, for its part, is closer to the friends of cohesion in wanting to maintain a strong CAP, but also wants a stronger expense in defence.

The problem of "rebates

And if all these variables were not enough, we have to add the figure of the compensatory cheques or "rebates. These are discounts to a country's contribution to budget. This figure was created in 1984 for the United Kingdom, during the presidency of the conservative Margaret Thatcher. For the "Iron Lady", the amount that her country contributed to budget was excessive, as most of the amount (70%) went to the CAP and the Cohesion Funds, from which the UK hardly benefited. It was therefore agreed that the UK would have certain discounts on its budgetary contribution on a permanent and full basis.

And if all these variables were not enough, we have to add the figure of the compensatory cheques or "rebates. These are discounts to a country's contribution to budget. This figure was created in 1984 for the United Kingdom, during the presidency of the conservative Margaret Thatcher. For the "Iron Lady", the amount that her country contributed to budget was excessive, as most of the amount (70%) went to the CAP and the Cohesion Funds, from which the UK hardly benefited. It was therefore agreed that the UK would have certain discounts on its budgetary contribution on a permanent and full basis.

These compensatory cheques have since been given to other net contributor countries, but these had to be negotiated with each MFF and were partial on a specific area such as VAT or contributions. An unsuccessful attempt was already made to eliminate this in 2005.

For the frugal and Germany these cheques should be kept, on civil service examination to the friends of cohesion and especially France, who want them to disappear.

Sánchez seeks his first victory in Brussels

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is staking much of his credibility in both Europe and Spain on these negotiations.

In Europe, for many he failed in the negotiations for the new Commission. Sánchez started from a position of strength as the leader of Europe's fourth Economics after the UK's exit. He was also the strongest member of the Socialist group parliamentary , which has been in the doldrums in recent years at the European level, but was the second strongest force in the European Parliament elections. For many, therefore, the election of the Spaniard Josep Borrell as High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, with no other socialist in key positions, was seen as a failure.

Sánchez has the opportunity in the negotiations to show himself as a strong and reliable leader so that the Franco-German axis can count on Spain to carry out the important changes that the Union has to make in the coming years.

On the other hand, in Spain, Sánchez has the countryside up in arms over the prospects of reducing the CAP. And much of his credibility is at stake after his victory in last year's elections and the training of the "progressive coalition" with the support of Podemos and the independentistas. The Spanish government has already taken a stand with farmers, and cannot afford a defeat.

Spanish farmers are highly dependent on the CAP. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food: "in 2017, a total of 775,000 recipients received 6,678 million euros through this channel. In the period 2021-2027 we are gambling more than 44,000 million euros."

There are two different types of CAP support:

-

Direct aids: some are granted per volume of production, per crop (so called "coupled"), and the others, the "decoupled" ones, are granted per hectare, not per production or yield and have been criticised by some sectors.

-

Indirect support: this does not go directly to the farmer, but is used for the development of rural areas.

The amount of aid received varies depending on the sector, but can amount to up to 30 % of a farmer's income. Without this aid, a large part of the Spanish countryside and that of other European countries cannot compete with products coming from outside the Union.

Failure of the first budget summit

On 20 and 21 February an extraordinary summit of the European committee took place in order to reach a agreement. It did not start well with the proposal of the president of the committee, Charles Michel, for a budget based on 1.074% of GNI. This proposal convinced nobody, neither the frugal as excessive, nor the friends of cohesion as insufficient.

Michel's proposal included the added complication of linking the submission of aid to compliance with the rule of law. This measure put the so-called Visegrad group (Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia) on guard, as the rule of law in some of these countries is being called into question from the west of the Union. So, another group is taking centre stage.

The Commission's technical services made several proposals to try to make everyone happy. The final one was 1.069% of GNI. Closer to 1%, and including an increase in rebates for Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Austria and Denmark, to please the frugal and attract the Germans. But also an increase in the CAP to please the friends of cohesion and France, at the cost of reducing other budget items such as funding for research, defence and foreign affairs.

But the blocs did not budge. The frugal ones remain entrenched at 1%, and the friends of cohesion in response have decided to do the same, but at the 1.3% proposed by the European Parliament (even if they know it is unrealistic).

In the absence of agreement Michel dissolved the meeting; it is expected that talks will take place in the coming weeks and another summit will be convened.

Conclusion

The EU has a problem: its ambition is not matched by the commitment of its member states. The Union needs to reinvent itself and be more ambitious, say its members, but when it comes down to it, few are truly willing to contribute and deliver what is needed.

The Von der Leyen Commission arrived with three star plans: the European Green Pact to make Europe the first carbon-neutral continent; digitalisation; and, under Josep Borrell, greater international involvement on the part of the Union. However, as soon as the budget negotiations began and it became clear that this would lead to an increase in the expense, each country pulled in its own direction, and it was these subject proposals that were the first to fall victim to cuts due to the impossibility of reaching an understanding.

A agreement has to be reached by 31 December 2020, if there is to be no money at all: neither for CAP, nor for rebates, nor even for Erasmus.

Member States need to understand that for the EU to be more ambitious they themselves need to be more ambitious and willing to be more involved, with the increase in budget that this entails.

Georgian aspirations for EU and NATO membership meet Western fears of Russian overreaction

![View of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, with the presidential palace in the background [Pixabay]. View of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, with the presidential palace in the background [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/georgia-blog.jpg)

▲ View of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, with the presidential palace in the background [Pixabay].

ANALYSIS / Irene Apesteguía

In Greek times, Jason and the Argonauts set out on a journey in search of the Golden Fleece, with a clear direction: the present-day lands of Georgia. Later, in Roman times, these lands were divided into two kingdoms: Colchis and Iberia. From being a Christian territory, Georgia was conquered by the Muslims and later subjected to the Mongols. At this time, in the 16th century, the population was reduced due to continuous Persian and Ottoman invasions.

In 1783, the Georgian kingdom and the Russian Empire agreed to the Treaty of Georgiyevsk, in which the two territories pledged mutual military support. This agreement failed to prevent the Georgian capital from being sacked by the Persians, which was allowed by the Russian Tsar. It was the Russian tsar, Tsar Paul I of Russia, who in 1800 signed the corresponding incorporation of Georgia into the Russian empire, taking advantage of the moment of Georgian weakness.

After the demise of the Transcaucasian Federal Democratic Republic and thanks to the Russian collapse that began in 1917, Georgia's first modern state was created: the Democratic Republic of Georgia, which between 1918 and 1921 fought with the support of German and British forces against the Russian Empire. Resistance did not last, and occupation by the Russian Red Army led to the incorporation of Georgian territory into the Union of Soviet Republics in 1921. In World War II, 700,000 Georgian soldiers had to fight against their former German allies.

In those Stalinist times, Ossetia was divided in two, with the southern part becoming an autonomous region belonging to Georgia. Later, the process was repeated with Abkhazia, thus forming today's Georgia. Seventy years later, on 9 April 1991, the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic declared its independence as Georgia.

Every era has its "fall of the Berlin Wall", and this one is characterised by the disintegration of the former Russia. The major armed conflict that was to unfold in 2008 as a result of the frozen conflicts between Georgia and South Ossetia and Abkhazia since the beginning of the last century came as no surprise.

Since the disintegration of the USSR

After the break-up of the USSR, the territorial configuration of the country led to tension with Russia. Independence led to civil unrest and a major political crisis, as the views of the population of the autonomous territories were not taken into account and the laws of the USSR were violated. As twin sisters, South Ossetia wanted to join North Ossetia, i.e. a Russian part, with Abkhazia again following in their footsteps. Moscow recognised Georgia without changing its borders, perhaps out of fear of a similar action to the Chechen case, but for two long decades it acted as the protective parent of the two autonomous regions.

With independence, Zviad Gamsakhurdia became the first president. After a coup d'état and a brief civil war, Eduard Shevardnadze, a Georgian politician who in Moscow had worked closely with Gorbachev in articulating perestroika, came to power. Under Shevardnadze's presidency, between 1995 and 2003, ethnic wars broke out in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Around ten thousand people lost their lives and thousands of families fled their homes.

In 2003 the Rose Revolution against misrule, poverty, corruption and electoral fraud facilitated the restoration of territorial integrity, the return of refugees and ethnic acceptance. However, the democratic and economic reforms that followed remained a dream.

One of the leaders of the Rose Revolution, the lawyer Mikhail Saakashvili, became president a year later, declaring Georgian territorial integrity and initiating a new policy: friendship with NATO and the European Union. This rapprochement with the West, and especially the United States, put Moscow on notice .

Georgia's strategic importance stems from its geographic centrality in the Caucasus, as it is in the middle of the route of new oil and gas pipelines. European energy security underpinned the EU's interest in a Georgia that was not subservient to the Kremlin. Saakashvili made nods to the EU and also to NATO, increasing the issue of military troops and expense in armaments, something that did him no harm in 2008.

Saakashvili was successful with his policies in Ayaria, but not in South Ossetia. Continued tension in South Ossetia and various internal disputes led to political instability, which prompted Saakashvili to leave Withdrawal .

At the end of Saakashvili's term in 2013, commentator and politician Giorgi Margvelashvili took over the presidency as head of the Georgian Dream list. Margvelashvili maintained the line of rapprochement with the West, as has the current president, Salome Zurabishvili, a French-born politician, also from Georgian Dream, since 2018.

Fight for South Ossetia

The 2008 war was initiated by Georgia. Russia also contributed to previous bad relations by embargoing imports of Georgian wine, repatriating undocumented Georgian immigrants and even banning flights between the two countries. In the conflict, which affected South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Saakashvili had a modernised and prepared army, as well as full support from Washington.

The battles began in the main South Ossetian city of Tskhinval, whose population is mostly ethnic Russian. Air and ground bombardments by the Georgian army were followed by Russian tanks on the territory of entrance . Moscow gained control of the province and expelled the Georgian forces. After five days, the war ended with a death toll of between eight hundred and two thousand, depending on the different estimates of each side, and multiple violations of the laws of war. In addition, numerous reports commissioned by the EU showed that South Ossetian forces "deliberately and systematically destroyed ethnic Georgian villages". These reports also stated that it was Georgia that initiated the conflict, although the Russian side had engaged in multiple provocations and also overreacted.

Following the 12 August ceasefire, diplomatic relations between Georgia and Russia were suspended. Moscow withdrew its troops from part of the Georgian territory it had occupied, but remained in the separatist regions. Since then, Russia has recognised South Ossetia as an independent territory, as do Russian allies such as Venezuela and Nicaragua. The Ossetians themselves do not acknowledge cultural and historical ties with Georgia, but with North Ossetia, i.e. Russia. For its part, Georgia insists that South Ossetia is within its borders, and the government itself will take care of it as a matter of law and order, thus solving a problem described as constitutional.

Given Georgia's rapprochement with the EU, the conflict prompted European diplomacy to play an active role in the search for peace, with the deployment of 200 observers on the border between South Ossetia and the rest of Georgia, replacing Russian peacekeepers. In reality, the EU could have tried earlier to react more forcefully to Russia's actions in South Ossetia, which some observers believe would have prevented what happened later in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. In any case, despite initiating the conflict, this did not affect Tbilisi's relationship with Brussels, and in 2014 Georgia and the EU signed a agreement of association. Today it is safe to say that the West has forgiven Russia for its behaviour in Georgia.

The war, although short, had a clear negative impact on the Ossetian region's Economics , which in the midst of difficulties became dependent on Moscow. However, Russian financial aid does not reach the population due to the high level of corruption.

The war is over, but not the friction. In addition to a refugee problem, there is also a security problem, with Georgians being killed on the border with South Ossetia. The issue is not closed, but even if the risk is slight, everything remains in the hands of Russia, which in addition to controlling and influencing politics, runs tourism in the area.

This non-resolution of the conflict hampers the stabilisation of democracy in Georgia and with it the possible entrance accession to the European institution, as ethnic minorities claim a lack of respect for and protection of their rights. Although governance mechanisms remain weak in these conflicts, it is clear that recent reforms in the South Caucasus have led to promote inclusive dialogue with minorities and greater state accountability.

Latest elections

November 2018 saw the last direct presidential elections in the country, as from 2024 it will no longer be citizens who vote for their president, but legislators and certain compromisers, due to a constitutional reform that transforms the country into a parliamentary republic.

In 2018, candidate of the United National Movement, Grigol Vashdze, and the Georgian Dream candidate, Salome Zurabishvili, faced each other in the second round. With 60% of the vote, the centre-left candidate became the first woman president of Georgia. She won on a European platform: "more Europe in Georgia and Georgia in the European Union". Her inauguration was greeted by protesters alleging election irregularities. The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) endorsed the election process, but noted a lack of objectivity in the public media during the campaign.

Some Georgian media consider that Georgian Dream enjoyed an 'undue advantage' because of the intervention in the campaign of former prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili, now a wealthy financier, who publicly announced a financial aid programme for 600,000 Georgians. It became clear that Ivanishvili pulls the strings and levers of power in the country. This questioning of the cleanliness of the campaign has led to Georgia's downgrading of democratic quality in the 2018 ratings.

![Public event presided over in January by Salome Zurabishvili at the Georgian presidential palace [Presidency of Georgia]. Public event presided over in January by Salome Zurabishvili at the Georgian presidential palace [Presidency of Georgia].](/documents/10174/16849987/georgia-blog-3.jpg)

Public event presided over in January by Salome Zurabishvili at the Georgian presidential palace [Presidency of Georgia].

THE APPROACH TO THE WEST

Since the policies pursued by the Georgian presidency since Saakashvili came to power, Georgia has made a determined move into the Western world. Thanks to all the new measures that Tbilisi is implementing to conform to Western demands and requirements , Georgia has managed to profile itself as the ideal candidate for its entrance in the EU. However, despite the pro-European and Atlanticist yearnings of the ruling Georgian Dream party and a large part of Georgian society, the country could end up surrendering to Russian pressure, as has happened with several former Soviet territories that had previously attempted a Western rapprochement, such as Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan.

EU compliance

Becoming the most favoured country in the Caucasus to join the European Union, with which it has a close and positive relationship, Georgia has signed several binding treaties with Brussels, following the aspiration of Georgian citizens for more democracy and human rights. In 2016 the agreement of association entered into force between the EU and Georgia, allowing for serious steps in political and economic integration, such as the creation of the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA). This preferential trade regime makes the EU the country's main trading partner partner . The DCFTA financial aid encourages Georgia to reform its trade framework , following the principles of the World Trade Organisation, while eliminating tariffs and facilitating broad and mutual access. This alignment with the EU's framework legal framework prepares the country for eventual accession.

As for agreement of association, it should be mentioned that Georgia is a member country of the association Eastern under the European Neighbourhood Policy. Through this association, Brussels issues annual reports on the steps taken by a given state towards closer alignment with the EU. The committee of association is the formal institution dedicated to monitoring these partnership relations; its meetings have highlighted the progress made and the growing closeness between Georgia and the EU.

In 2016 the EU's Permanent Representatives committee confirmed the European Parliament's agreement on visa liberalisation with Georgia. This agreement was based on visa-free travel for EU citizens crossing the country's borders, and for Georgian citizens travelling to the EU for stays of up to 90 days.

Georgia, however, has been disappointed in its expectations when the EU has expressed doubts about the desirability of membership. Some EU member states cited the potential danger posed by Georgian criminal groups, which several pro-Russian parties in the country took advantage of to wage a vigorous campaign against the EU and NATO. The campaign paid off and anti-Russian opinion waned, prompting Moscow to assert itself further with military manoeuvres, although public support for the Georgian Dream continued in the 2016 elections.

Despite the lack of any prospect of forthcoming accession, the EU continues to offer hope, as in German Chancellor Angela Merkel's tour of the Caucasus last summer. On her visit to Georgia, Merkel compared the Georgian conflict to the Ukrainian conflict due to the presence of Russian troops in the country's separatist regions. She visited the town of Odzisi, located on the border with South Ossetia, and at a speech at the University of Tbilisi said that both that territory and Abkhazia are "occupied territories", which did not go down well with Moscow. Merkel pledged to do her utmost to ensure that this "injustice" remains present on the international diary .

Georgian President Salome Zourachvili also believes that the UK's exit from the EU could be a great opportunity for Georgia. "It will force Europe to reform. And being an optimist, I am sure it will open new doors for us," she said.

Hope in the Atlantic Alliance

Russia's behaviour in recent years, in addition to encouraging Georgia's rapprochement with the EU, has given a sense of urgency to its desire to join the Atlantic Alliance.

In 2016, several joint NATO-Georgia manoeuvres took place in the Black Sea, where a coalition fleet was stationed. This was evidence of a growing mutual rapprochement that Georgia hoped would lead to NATO membership at that year's NATO summit in Warsaw. But despite the country's extensive defence, security and intelligence training, it was not invited to join the club: Russia was not to be inconvenienced.

NATO assured, however, that it would maintain its open-door policy towards eastern countries and considered Georgia to remain an exemplary candidate . Pending future decisions, Tbilisi was left with strengthening military cooperation, offering as an incentive the "Black Sea format", a compromise solution that includes NATO, Georgia and Ukraine and increases NATO's influence in the Black Sea region.

Georgia, as the capital ally of NATO and the European Union in the Caucasus region, aspires to greater protection from the Atlantic Alliance vis-à-vis Russia. The European political centre observes the Georgian population's efforts to join the international organisation and opts for a strategy of patience for the Caucasus region, as in the Cold War years.

Approaching Russia's borders is problematic, and multiple criticisms have been levelled at NATO over the easy Georgian membership due to its geostrategic status . Russia has repeatedly expressed concern about such joint cooperation between the US, NATO and neighbouring Georgia.

![President Zurabishvili's speech at the Holocaust remembrance events in Jerusalem in January [Presidency of Georgia]. President Zurabishvili's speech at the Holocaust remembrance events in Jerusalem in January [Presidency of Georgia].](/documents/10174/16849987/georgia-blog-2.jpg)

President Zurabishvili's speech at the Holocaust remembrance events in Jerusalem in January [Presidency of Georgia].

A VIGILANT RUSSIA

The wounds of the 2008 South Ossetia war have not yet healed in Georgian society. Despite Georgia's political attempts at rapprochement with Western institutions, Russia remains suspiciously vigilant, so that relations between the two countries continue to be troubled. Last summer saw the latest episode of tension, which led the Georgian president to describe Russia as an "enemy and occupier".

After some rapprochement in 2013 that saw an increase in food trade and Russian tourism coming to the country, Moscow has shifted to a strategy of attempting rapprochement at the religious and political level. With that intention, a small group of Russian lawmakers travelled to the Georgian capital for the Orthodox Interparliamentary Assembly. This international organisation, led by Greece and Russia, is the only one that brings together the legislative bodies of Orthodox countries. The meeting took place in the plenary hall of the Georgian Parliament, where Russian MP Sergei Gabrilov took the seat of the Speaker of the House. Several politicians from the civil service examination did not take kindly to this and mobilised thousands of citizens, who staged serious public disorder in an attempted storming of the Parliament. The Russian delegation was forced to leave the country, but the attempt at Russian influence through religion was clear, whereas until then the Church had kept out of all political controversies.

The riots, in which many people were injured, prompted members of the government to cancel all foreign travel and the president to cut short her trip to Belarus, where she was to attend attend the opening of the European Games, a presence considered important in Western eyes. Demonstrators protested against the Georgian Dream headquarters, where they burned and stormed outbuildings. The ten days of rioting were not only justified by the incident at the Assembly, but also as a reaction to the Russian occupation. In addition, the conflict between the Georgian Dream and the opposing parties led by Saakashvili, now in exile in Ukraine, may also have contributed.

The crisis ended with the departure of Prime Minister Mamuka and the appointment of Georgi Gaharia as his successor, despite criticism that he had been criticised for his management of the unrest as interior minister.

The uprisings, while well-intentioned, are against Georgia's interests, the Georgian president said, as what the country needs is "internal calm and stability", both to progress internally and to gain sympathy among EU members, who do not want more tension in the region. Salome Zurabishvili warned of the risks of any internal destabilisation that Russia could provoke.

In the wake of the June protests, the Kremlin issued a decree banning the transport of nationals to Georgia by Russian airlines. While claiming to ensure "national security and protection of citizens", it was clear that Moscow was reacting to an anti-Russian tinged revolt. The decision reduced visitor arrivals from Russia, which had been accounting for one in four tourists, which the government said could mean a loss of $1 billion and a 1 per cent reduction in GDP.

The tension reached the television media in the Georgian capital. Days after the riots, the host of Rustavi 2's 'Post Scriptum' programme intervened in the broadcast speaking Russian and hurled several insults at President Vladimir Putin, which Russia described as unacceptable and 'Russophobic'. The channel apologised, admitting that its ethical and editorial standards had been violated, while several Georgian politicians, including the president, condemned the episode and lamented that such acts only increase tensions between the two nations.

The events of last summer show Georgians' rejection of an enmity with Russia that, in addition to heightening tensions with the big northern neighbour, may have an impact on Georgia's relationship with the EU and other Western international organisations, as they will not tread on quicksand, especially with big Russia in front of them.

REFERENCES

Asmus, Ronald D. A Little War That Shook the World. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010.

Cornell S. E. & Starr, F. The Guns of August 2008. Russia's War in Georgia. London: M.E. Sharpe, 2009.

De la Parte, Francisco P. The Returning Empire. La Guerra de Ucrania 2014-2017: Origen, development, entorno internacional y consecuencias. Oviedo: Ediciones de la Universidad de Oviedo, 2017.

Golz, Thomas. Georgia Diary: A Chronicle of War and Political Chaos in The Post-Soviet Caucasus.New York: Taylor and Francis, 2006.

The UN Conference did little to increase international commitment to climate change action, but did at least boost the assertiveness of the EU

In recent years, the temperature of the Earth has risen, causing the desertification of lands and the melting of the Poles. This is a major threat to food production and provokes the rise of sea levels. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has concluded that there is a more than 95% probability that human activities over the past 50 years are the cause of global warming. Since 1995 the United Nations has organized international meetings in order to coordinate measures to reduce CO2 emissions, which arguably are behind the increases in temperature. The latest meeting was the COP25, which took place in Madrid this past December. The COP25 could be labeled almost a missed opportunity.

ARTICLE / Alexia Cosmello and Ane Gil

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and United Nations Environment Programme. The IPCC's Fifth Assessment Report concluded that: "Climate change is real and human activities are the main cause". In recent years, rising temperatures on earth have contributed to the melting of the Polar Ice Cap and an increase in desertification. These developments have provoked the rise of sea levels and stresses on global food production, respectively.

In 1992, the IPCC formed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) with the goal of minimizing anthropogenic damage to the earth's climate. 197 countries have since ratified the UNFCCC, making it nearly universal. Since 1995, the UNFCCC has held an annual Conference of the Parties (COP) to combat climate change. These COPs assess the progress of national governments in managing the climate crisis, and establish the legally binding obligations of developed countries to combat climate change. The most significant international agreements emerging from UNFCCC annual COPs are the Kyoto Protocol (2005) and the Paris Agreement (2016). The most recent COP25(25th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) took place in Madrid in December 2019.

The previous conference(COP24) marked a significant improvement in international regulation for implementing the Paris Agreement, but crucially ignored the issue of carbon markets (Article 6). Thus, one of the main objectives of COP25 was the completion of an operating guide for the Paris Accords that included provisions for carbon market regulation. However, COP25 failed to reach a consensus on carbon market regulation, largely due to opposition from Brazil and Australia. The issue will be passed onto next year's COP26.

Another particularly divisive issue in COP25 was the low level of international commitment. In the end, only 84 countries committed to the COP25 resolutions; among them we find Spain, the UK, France and Germany. Key players such as the US, China, India and Russia all declined to commit, perhaps because together they account for 55% of global CO2 emissions. All states will review their commitments for COP26 in 2020, but if COP26 goes anything like COP25 there will be little hope for positive change.

COP25 also failed to reach an agreement on reimbursements for damage and loss resulting from climate change. COP15 set the goal of increasing the annual budget of the Green Climate Fund to 100 billion USD by 2020, but due to the absence of sufficient financial commitment in COP25, it appears that this goal will not be met.

It is worth noting that in spite of these grave failures, COP25 did achieve minor improvements. Several new policies were established and a variety of multilateral agreements were made. In terms of policies, COP25 implemented a global "Gender Action Plan," which will focus on the systematic integration of gender equality into climate policies. Additionally, COP25 issued a declaration calling for increased consideration of marine biodiversity. In terms of multilateral agreements, many significant commitments were made by a vast array of countries, cities, businesses, and international coalitions. Notably, after COP25, the Climate Ambitious Coalition now counts with the impressive support of 27 investors, 763 companies, 393 cities, 14 regions, and 70 countries.

But by far the saving grace of COP25 was the EU. The EU shone brightly during COP25, acting as an example for the rest of the world. And this is nothing new. The EU has been a forerunner in climate change action for over a decade now. In 2008, the EU established its first sustainability goals, which it called the "2020 Goals". These goals included: reducing GHG emission by 20% (compared to 1990), increasing energy efficiency by 20%, and satisfying a full 20% of total energy consumption with renewable energy sources. To date, the EU has managed not merely to achieve these goals, but to surpass them. In fact, by 2017, EU GHG emissions had been reduced not just by 20%, but by 22%.