In the picture

Satellite image of the Aegean, with Greece at the top and Turkey at the bottom [NASA].

Tensions in the Aegean Sea between Greece and Turkey, mainly linked to territorial aspects, represent a threat to peace and security in Europe. Although the conflict is currently experiencing a moment of détente (after a brief verbal escalation prior to the elections held in both countries in spring 2023), it is crucial to understand the historical and geopolitical complexity that has led to this status.

The dispute in the Aegean Sea has gained strategic relevance, especially in light of the war in Ukraine, which has highlighted the importance of access to the Aegean from the Black Sea in order to secure grain traffic, essential for global markets. Instability in the region underscores the need to maintain peace in the Aegean, where tensions between Greece and Turkey have been a constant.

The instructions of the dispute

The relevance of the Aegean Sea, in geopolitical and strategic terms, has its origins in remote antiquity. Since the dawn of civilization in the area of the Tigris and Euphrates, this space has acted as a bridge in trade relations and cultural exchange between the West and the East. It has also been the scene of confrontation, as the Iliad and the Odyssey remind us. Its geostrategic value is further enhanced by the fact that the Aegean Sea is the natural route linking the Black Sea and the Mediterranean through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits.

This circumstance has shaped the perception of the region that Turks, Greeks and the rest of Europeans have shaped over time. Its importance has also been captured by modern geopolitics. Mackinder, for example, placed it in a privileged location in the Inner Crescent surrounding the Heartland, while Spykman identified Cyprus and the Aegean Sea as part of the Rimland, a geographic zone core topic of geopolitical power leading to world control.

During classical antiquity, the entire Aegean Sea area was incorporated into the Greek and Hellenistic cultural sphere. Great Ionian cities such as Ephesus, Miletus, Smyrna, or Halicarnassus, all of them in Asia Minor, speak of the cultural unity prevailing in antiquity in this wide geographical contour, which was maintained for several centuries thanks to Byzantium.

The Ottoman conquest of the Byzantine Empire, culminating in the capture of Constantinople in 1453, marked the beginning of a new social and political order in the region. As a consequence of this historical event, the Aegean Sea gravitated towards the Turkish orbit, into which it became fully integrated, replacing Greek culture until the end of the First World War. The Ottoman conquest unified the Aegean for several centuries, but triggered the division of society into religious communities, which left an imprint on the respective identities of Greek and Turkish civilizations. This adds a further layer of geopolitical complexity, on top of the geographical one already noted above: from the very realist theory of international relations Huntington warns of the relevance of the friction between civilizations.

The conflict began to manifest itself at the beginning of the 19th century, with the beginning in 1821 of the process of Greek independence and the subsequent process of Greek nation-building. Independence, however, did not fulfill the territorial aspirations of Greek nationalism, inspired by the 'Great Idea'(Μεγάλη Ιδέα), a concept born in 1844, which encapsulates the Greek vision of territorial expansion, rooted in the will to rebuild the self-referential space that the Hellenes had during the Byzantine Empire. This territorial vision, deeply rooted in the national identity, aspires to integrate not only what is Greece today but also Anatolia, Turkish Thrace, including Constantinople, the whole of Macedonia and Epirus, as well as the island of Cyprus and all the Aegean islands, including Crete.

Thus, the process of Greek nation-building at the expense of the Ottoman Empire continued after formal independence. At the outbreak of World War I, Greece exercised sovereignty over a large part of the Aegean islands, including the islands of Samos and Icaria, both held by Italy since the Italo-Turkish war of 1912, and integrated into Greece in 1912 and 1913 respectively. Outside their control were the Dodecanese islands, occupied by Italy during the war and which would still take more than thirty years to return to Greek control.

During World War I, the Ottoman Empire, an ally of the Axis Powers, suffered a significant defeat and would eventually collapse in 1922. After the war, the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) established new borders for the Ottoman territory. In the context of the dispute in the Aegean Sea, the treaty granted Greece certain rights and sovereignty over several islands (Imbros, Lemnos and Tenedos), as well as over Eastern Thrace, the Smyrna region and the west coast of Anatolia.

The Treaty of Sèvres never came into force, as a consequence of the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish war. The Treaty of Lausanne (1923) put an end to that war and led to the international recognition of the new Republic of Turkey as the successor to the Ottoman Empire. The new treaty clearly defined the borders between Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey. Thus, Turkey formally renounced claims to several territories, including the Dodecanese, Cyprus, Egypt, Sudan, Syria and Iraq. However, it reverted sovereignty over the islands of Imbros and Tenedos to Turkey. Lemnos remained under Greek sovereignty.

The Treaty of Lausanne also incorporated a agreement on exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, which also raised significant tensions and questions. Under the treaty, massive population exchanges took place between the two countries in 1923 that radically changed the ethnic distribution of the region, generating great discontent among the ethnic and religious minorities affected by them. An estimated 1.6 million Greeks were forced to leave their residences in Anatolia, while approximately 670,000 Greek Turks were transferred to Turkey.

The Montreux Convention (1936) regulated the status of the Dardanelles Strait and the Bosporus, limiting military presence in the region. The Paris Peace Treaty (1947), which ended World War II, provided specific provisions on the demilitarization of the Aegean islands and established the transfer of the Dodecanese to Greek sovereignty.

With the onset of the Cold War, Greece and Turkey became members of NATO in 1952, strengthening their partnership due to their strategic importance in the face of the Soviet threat in the Balkans, the Bosporus and the Mediterranean Sea. With the two countries formally becoming allies, the possibility of friction in the Aegean escalating into open conflict was reduced. During this period, moreover, Turkey sought a diplomatic rapprochement with the European Economic Community that culminated in the signature of the Treaty of Ankara (1963), which created a association between the EEC and Turkey.

Rocks and conflicts

The convergence of the two nations in shared partnerships has not, however, avoided episodes of tension. The one that has gone the furthest concerns Cyprus. This eastern Mediterranean island was ceded by the Ottoman Empire to Britain in 1878 and was a British colony until it became independent in 1960. The conflict in Cyprus began in the 1950s with the training of EOKA, a Greek Cypriot organization that sought the expulsion of British forces and the union of the island with Greece. After independence, tensions between the Greek and Turkish communities led to UN intervention in 1964. In 1974, a coup backed by the military board ruling Greece provoked the Turkish invasion, dividing the island and creating the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), recognized only by Turkey.

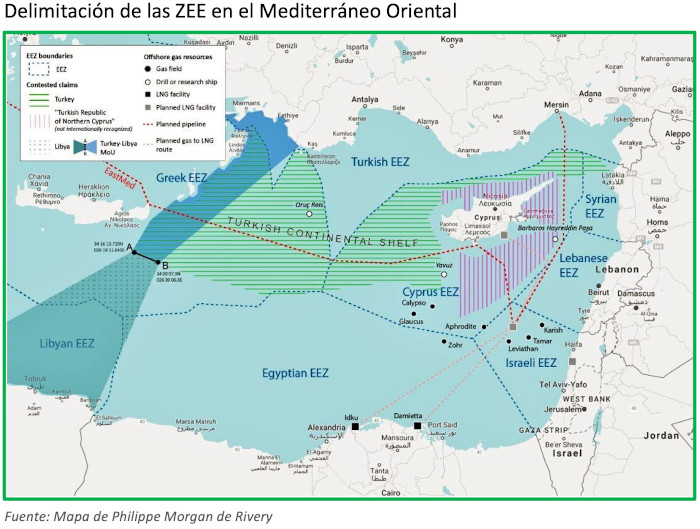

Reunification talks on the island have been difficult, and the last summit resulted in a stalemate, with the Greek Cypriot side advocating a federative republic and the Turkish Cypriot side insisting on two independent republics. Recently, friction in relation to Cyprus has revolved around the finding of hydrocarbon deposits in maritime areas of its exclusive economic zone.

If this is the case in the Eastern Mediterranean, in the Aegean friction has arisen as a result of various actions carried out by the parties. One of them is the militarization of some of the Aegean islands. Despite the fact that the Treaty of Lausanne does not allow the construction of fortifications or naval instructions on the islands and the Treaty of Paris prohibits the militarization of the Dodecanese, in the early 1950s Greece began to deploy military units on some islands such as Lesbos, Samos, Chios and Icaria, keeping the militarization secret until the Cyprus Peace Operation in 1974.

Despite Turkey's international complaints, Greece maintains this militarization, which it justifies by selectively invoking the Montreux Convention. Turkey claims that these actions have no legal basis and are contrary to established treaties.

A particularly sensitive moment occurred in Imia in 1995. Imia-Kardak are two uninhabited islets whose control is disputed by both countries. After a series of secret landings by the armies of both sides, tensions around the two islands came close to triggering an armed conflict, which was averted thanks to NATO's diplomatic intervention. The same decade also saw the infiltration of numerous Turkish secret agents into Greece, who set off a series of large-scale fires. In response to these actions, some Greek citizens set fires in forested areas located in Turkish territory.

Another episode of tension was experienced more recently, when Turkey deployed the seismic exploration vessel 'Oruc Reis', sent in 2019 to the area of Kastelorizo in what was supposed to be a gas exploration mission statement . In Greece's eyes, this was an illegal act infringing on its sovereignty. The status was then further complicated by the Turkish decision to convert the Hagia Sophia temple in Istanbul into a mosque. The escalation of tension involved the deployment of Turkish scout ships and the violation of Greek airspace by Turkish aircraft.

The latest diplomatic clash involved Turkish aircraft on NATO's mission statement 'Nexus Ace' in December 2022. NATO's AWACS warning and control system, as well as two Turkish F-16 fighters participating in the mission statement in the Aegean Sea, were intercepted by Greek F-16s. NATO warned that the action did not reflect the spirit of the Alliance.

Beyond issues of territorial sovereignty and airspace, the relationship between Greece and Turkey has been damaged by emigration to Europe allowed or even encouraged by Ankara, especially of refugees from the Syrian conflict, leading to the migration crisis of 2015 and then to some brief episodes of recurrence in 2020 or 2022.

The two governments have also clashed over the Turkish Muslim minority living in Western Thrace, in northwestern Greece, near the Turkish border. Ankara accuses the Greek government of not fulfilling its commitments to that minority in areas such as Education, religious affairs and recognition of their ethnic identity.