Biological Ethics

Table of contents

Chapter 11. Interactions of Biology and Anthropology, II: Mankind

A. Llano

a) Animal behaviour and human behaviour

One of the most important cultural consequences of evolutionary transformationism is that it tends to minimise the differences between man and animals. In this it is perfectly consistent. For if the cosmos is basically a set of undifferentiated subject , governed by external mechanisms, there can be no intrinsic - or, as philosophers say, essential - distinctions between the various organisms, nor between the behaviour of the living subject and the intelligent behaviour of man. As already noted, transformational evolutionism is either reductionist or preformationist. Either it thinks that life and intelligence are nothing more than organised subject , or it believes that subject has always possessed the capacity to organise itself vitally and to reflect on itself. Consequently, for neither version of materialistic evolutionism is anything really new produced (this is the central paradox of ideological evolutionism: it ends up eliminating any real innovative evolution).

Reductionism has all the prestige of the "scientific worldview" in its favour, and was maintained by "progressive" scientists and philosophers from the 18th century until very recently. It is curious, however, to observe how more recently materialist approaches are leaning towards a pre-formationism that until recently was considered a conservative and mythical position. It had been advocated by the romantic biology of the 19th century in the face of scientistic and enlightened evolutionism. It was maintained, for example, by Schelling against Kant. Darwinism was clearly reductionist. Neo-Darwinism, on the other hand, is much less so. And, for its part, the determinism towards which some cultivators of cell biology tend to lean to a certain extent towards pre-formationism1. Although others warn, more accurately, that evolutionary programmes admit a margin of variation; something similar to the embryonic development would happen in them, which follows its own programme, although the evolutionary processes - which have a much longer period of time - are not rigorously determined as the latter is.

The more deterministic cell biologists stress, following Schrödinger, that "life seems to be an ordered and law-governed behaviour of the subject; a behaviour which is not based on the tendency of the subject to pass from order to disorder, but which is partly based on an order which is conserved"2 . Thus, life has not begun and seems to be inherent in the structure of the universe. According to this, life could be defined in the following terms: it is a process by which the universe is divided into two parts, one of which confronts and inspects the other. And an organism would be precisely one of the mirrors that the universe uses to look at itself3. Thus, not only life, but even consciousness, would be preformed in the subject from the beginning. The subject itself would have, beforehand, the capacity to organically organise itself and to think itself.

In any case, reductionism and preformationism - and, in a more nuanced way, scientistic fulgurationism - coincide in maintaining that there are no essential differences between inert beings, living organisms and humans.

We will not go into the novelty of the appearance of living things here. It suffices to refer to the opposing conceptions of the world that we have discussed in previous sections, to see that naturalistic finalism does not share the reductionist or preformationist approaches. It considers that the appearance of life is an essential innovation, a new update of the potentialities of the subject; an innovation that does not require the presence of mysterious vitalist principles, but of a new structural form of the subject. Nor does the special intervention of the creative Cause seem indispensable to explain the "passage" from the inert to the living. Even if there are no scientific reasons to exclude it, it is enough to admit - on a metaphysical level - the stable conservative and provident action of the transcendental Cause.

Let us focus on a much more radical and decisive innovation: the emergence of man. Because if it seems admissible that the inert subject could become organised - by the update of its potentialities - in subject alive, there is no scientific reason whatsoever that could explain the emergence of intelligence and freedom of man from animals. We will try to prove this assertion. But first, let us reflect for a moment on the cultural consequences - mentioned above - of including man in the random or implacable process of transformational evolutionism. If man is only a moment in the evolutionary process, if his consciousness can be reduced to physical causes or found already in animals (or even in the primordial soup), then the foundation of the very special human dignity evaporates. Man would be a sophisticated fragment of subject. And the ontological basis of ethics would vanish. Morality would be reduced to a simple intraspecific solidarity: I do not harm you, so that you do not harm me (or, more crudely, as Löw says: I scratch your back and you scratch mine).

A serious scientific and philosophical discussion has to start from a comparative research of animal behaviour and human behaviour. Contemporary ethology and the philosophical anthropology of our century provide us with sufficient and rigorous elements to establish this confrontation.

specialization animal: instinctive behaviour

Jakob von Uexküll can be considered the initiator of present-day ethology. He is one of the first scientists who succeeded in directing his research along the lines of overcoming atomism and mechanicism, which - from the beginning of this century - opened up new and promising paths for natural and human sciences. Uexküll succeeded in breaking the alternative between reductionist mechanicism and quasi-magical vitalism, to move towards a fruitful organicism that preludes a systemic and structural way of thinking.

Uexküll is also the initiator of the "Umweltforschung" or research of living environments, i.e. of Ecology. It is precisely he who introduced the notion of Umwelt: environment or peri-world. The "Umwelt" is the encompassing structural whole in which the organic being lives. The concept of environment is a biological notion: it is not a question of all the things that topographically surround the organism, because only those objective characteristics that have a vital significance for it are integrated into the "Umwelt" of an animal. The rest form an ignored background, since they do not pass through the "filter" of the senses, nor does the animal react to them. For example, the female tick possesses only three senses: smell, temperature and light. Thanks to a certain ability to detect light, she can position herself adequately on a branch. From there - with financial aid of the sense of smell and temperature - it can detect the passage of a warm-blooded animal, on which it drops to suck its blood. The perimundus is not a material or mechanical concept but, so to speak, a psychological one. The environment of a migratory bird, for example, does not include things that are physically close to it, precisely because they have no biological significance for it; on the other hand, it includes things that are far away: those of the habitat to which it is moving.

Certainly, introducing psychological notions into the explanation of animal behaviour runs the risk of falling into a certain anthropomorphism. But this risk is not inevitable: it is possible to make - and it is indeed possible to make - a strictly scientific animal psychology or ethology. However, if we do not introduce these "psychological" concepts, we run an even greater risk: that of reductionism. For it is very difficult - impossible - to explain animal behaviour in purely mechanical terms.

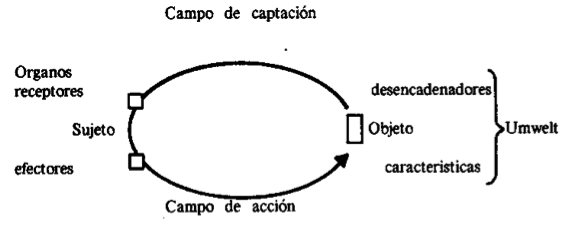

With these perspectives, Uexküll proposes the famous outline of the functional circle ("Funktionkreis") of animal experiences4. The structural unity of the "Umwelt", perimundus or environment, is divided into two fields: the field of uptake and the field of action. The former encompasses the system of characteristics grasped by the organism and the grasping system itself; the latter, the system of actions of the animal and its environment insofar as it is affected by these actions.

The outline proposed by Uexküll is as follows:

At the subjective pole of the perimundus are the organism's organs of uptake and action, while at the pole goal are the biologically relevant characteristics of the environment (which can be uptaken by a receptor of the organism) and the effects which the organism has on the environment. The unitary and closed nature of the perimundus is expressed by this circle, which has the character of a feed-back loop. Changes in the environment affect the organism that picks up on them, which then initiates behaviour aimed at restoring the balance of the system.

Today we know that Uexküll's outline is basically correct. For each animal species there is a fixed issue of triggers that determine a relatively similar or constant subject of behaviour for all individuals of the species. So the feeding, sexual, aggressive, etc. behaviour of these individuals is triggered when biologically significant events occur for each subject behaviour. Such triggers are fixed and constant for each species: you can know how many and what they are. They are genetically determined and correspond to specific behaviours. Thus, what is called animal specialization is determined by the fit between stimuli, receptors, effectors and "realities", i.e. objects from which the stimuli originate. Thus, thanks to this adjustment, a specific morphological specialization and also a specific behavioural specialization is achieved. The environment in which the animal lives also corresponds to this specialization. A "specialised" environment is what we call the ecological niche. The ecological niche is the system of triggers that trigger specific behaviours. If, by altering the ecological niche, some of these triggers are removed, two things can happen: either the receptors and effectors change and "reset" their specialization; or the animal does not survive.

From all this we can already see that the explanation of animal behaviour cannot be exhausted with the outline stimulus-response of classical behaviourism. According to this outline, any complex animal movement would be the sum of partial responses to a series of punctual stimuli. But this cannot explain relatively simple behaviours, such as chewing a food, let alone more complex behaviours, such as some nuptial "rites".

In reality, behaviourism - also as applied to animal behaviour - is a mechanistic simplification. This was already pointed out by the biologist and physician Kurt Goldstein in his 1934 work "The Structure of the Organism". The reactions to stimuli depend on their significance for the organism. And it is precisely the concept of significance that a mechanist refuses to accept, because he suspects - and rightly so - that it is a notion that implies a teleological view of living beings. But we know that there is nothing mysterious or unscientific about finalism. What is certain is that the appropriate stimuli are not mere physical realities: they are biological realities, integrated in the "Umwelt". What necessarily provokes a certain reflex response in the animal is not a physical causeChemistry: it is a physiological excitation - which only has significance for a specific organism - of which the physical-chemical agent is the occasion, rather than the cause. And the organism itself is not a mere system of forces tending to rest by the shortest way, as in the physical world, but an open thermodynamic system generating negative entropy, and tending not to rest but to action5.

Contemporary ethological research has shown that instinctive behaviour in animals is governed by innate triggering mechanisms (IRM). Instinctive activities are automatisms directed from the organic system: they have an endogenous character. Following the anthropologist Arnold Gehlen6 , instincts could be defined as stable forms of movement or innate, specialised and object-ordered behavioural patterns, which are triggered by highly specialised and typical excitators, which each animal species finds in its "Umwelt" or ecological niche, and towards which that species is genetically oriented. Although the elicitor usually triggers the instinctive behaviour, it should not be conceived of as its cause, nor the stereotyped movement that follows as a sum or combination of reactions to various elicitors. test The research of the ethologist Konrad Lorenz7 on objectless instinctive behaviour is a case in point. The most characteristic case is that of the starving starling that pursues a non-existent prey, reproducing "in a vacuum" the typical movements of its capture or ingestion. Thus, instinctive movements are provoked by an internal source of stimuli, and only the time and place of their manifestation is externally motivated. Therefore, the atomistic and mechanical outline of classical behaviourism cannot explain these structural behaviours.

Curious animal behaviour

But animal behaviour is not limited to instinctive behaviour. There are other forms of behaviour, involving orientation movements, "intelligent" resolution of new problems, and learning processes. These are non-instinctive types of behaviour, ways of behaving that are neither innate nor biologically predetermined. It is not innate, for example, for a fish swimming in a strong current to jump a particular obstacle in order to catch prey: it is the spontaneous resolution of an unprecedented and complicated hydrodynamic problem.

It has been shown that these types of behaviour are not evolutionarily derived from instincts and that there is even a certain tendency towards mutual exclusion. This dispels one of the clichés of Darwinian evolutionism, according to which animal "intelligence" and learning ability would increase as one moves up the phylogenetic ladder. In fact, this capacity is greater in animals with lower instinctual endowments or, if you prefer, more generalised instincts. It seems that the animals with the greatest capacity to solve new problems are arboreal, hunting and gregarious animals, irrespective of their taxonomic status .

Among this second series of non-instinctive processes, the "exploratory activity" or "curious behaviour" of many animals, which sometimes do not move in response to given stimuli, but rather search, explore, recognise new things, wander around curious. sample It is in this behavioural subject where the explanatory indigence of the outline stimulus-response is most clear, although neobehaviourists have introduced mediating factors that qualify the primitive model .

But, in addition, this subject of behaviour will help us to begin to realise the essential difference that exists between animal behaviour and human behaviour.

There is no doubt that exploratory activity and curiosity-driven learning occur in a variety of animal species. But Konrad Lorenz himself - who has described these phenomena so acutely, and is so little zealous in differentiating between animal and human - recognises that there is one feature that fundamentally distinguishes the curious behaviour of all animals from that of man. That of the former is only linked to a short phase of their first age8. In the adult animal, the desire for novelty is transformed into a violent repulsion against the unknown, so that a change in the environment can lead to bewilderment and even death. The learning of adult individuals stems only from a particular and very precise status ; and even in young individuals, it never transcends the sensitive complexes of the perimundum and the area of biological interests.

Objective conduct

On the contrary, we all have our own and other people's experience that human curiosity knows no bounds and certainly transcends biological interests altogether. Moreover, curiosity and exploratory activity are manifested in man from childhood to old age. His interest in objects is constant. His attention does not slip from one thing to another, but remains on the object, which presents itself as a stable focus of attention. The object thus acquires autonomy: it is no longer an element of the perimund, but something in itself, from which man can distance himself and observe it as it is, or try to produce something new out of it.

It is said that Michelangelo "saw" the figure he wanted to sculpt in the block of marble. There, in what was physically only a piece of stone, the artist guessed the form of his Moses. But, without rising to such artistic experiences, we can appreciate the objective conduct of man in very simple operations. In driving a nail into the wall, man's activity is stably fixed on the object itself, so that successive blows of the hammer change the direction of the nail itself, on which his attention is fixed. (No animal is capable of hammering a nail).

Lorenz has insisted that the dominant and most essential feature of curious behaviour in man is his direct relation to the object as such. It is the reference letter to the thing, the relation to the object, which leads to the active elaboration of an own contour, constituted by objects9. And this is notoriously unique to man.

And the fact is that man, properly speaking, does not have "Umwelt" or perimundum. He has a world ("Welt"). The animal lives embedded in its environment, which it carries structured with itself wherever it goes; it is immersed in the biological reality, biunivocally corresponding to its organic states, without ever apprehending it "objectively". Man, on the other hand, is autonomous in the face of the bonds and pressure of the organic.

This is how Max Scheler - the initiator of contemporary philosophical anthropology - qualified Uexküll's ideas. In reality, Uexküll, in spite of all his successes, used the expressions subject and object inappropriately when referring to animal behaviour. Only man is properly a subject, precisely because he alone is capable of elevating impulses to the status of objects. He can apprehend the very way of being of these objects, without being limited to a fixed environment or an ecological niche. Man is open to the world10.

Man has the capacity to know objects as such, i.e. as something distinct from the subject that confronts them. That is exactly what ob-iectum originally means: ob-iectum, that which lies in front of it (Gegen-stand, in German). If man is open to the world, it is because he has - in principle - the possibility of cognitive access to the totality of the objects that make up the world. He can therefore possess a projective knowledge - anticipating objects that have not yet presented themselves - and even a "knowledge of non-knowledge". It is capable of questioning and, as Nietzsche said, it can promise.

According to this status, it follows that human behaviour is oriented in a way that transcends the spatio-temporal schemas to which, due to its psychosomatic condition, it nevertheless remains bound to a certain extent. The graphic representation of such a "status" would be that of a helical line. On a first level, it hardly distances itself from the plane of biological needs, to whose demands it submits. But the very way in which it solves these problems places it in the realm of the objects themselves, which opens up an unlimited series of possibilities, which it tries to reach in stages in its biography staff and in the course of historical events.

1From a psychological perspective, Allport has pointed out that "the child and the adult are continually creating tensions in the form of new interests and far transcend the basic and safely established level of homeostasis; acquiring knowledge for the sake of acquiring it, the creation of beautiful or useful works, acts of love or inspired by a sense of duty... none of these can be reduced to the psychology of impulses"11.

Human unspecialisation

Human behavior has a suprabiological scope. That is why it cannot be schematized according to a functional circuit Closed. Thus, in the functional circle of experience proposed by Uexküll, it is necessary to introduce a triple censorship or cut: in the receptors, in the effectors, and in the connection between receptors and effectors. These ruptures are manifested in the fact that, once the stimulus is captured, the response is not automatically produced, but rather there is a hiatus between reception and action: before a given stimulus, a great variety of responses may be produced, or none at all. This shows that the receptive capacity of man has a power of elaboration -of formalization or symbolization- far superior to that of any animal. And that his School to act is mediated by a very high variability factor. As we shall see, we are dealing with intelligence and freedom, which, although they have a biological basis, cannot be of an organic nature.

This overcoming modification, which human conduct represents, is based on its reference letter to objective reality: on the capacity to elevate impulses to the category of objects. The concept of objective conduct provides us with the basis for understanding the most peculiar features that differentiate man from the animal: intelligence, technique, freedom and language.

The main biological characteristic of man is his unspecialisation. His receptors are unspecialised, his effectors are unspecialised, and his own body is unspecialised.

Man's somatic-psychic Structures is adapted to his universal openness to a world of objects. This was noticed by the ancient Philosophy and has been confirmed by current anthropology through empirical research.

Heraclitus had already asked: "Who will know the limits of the soul?"; and Aristotle formulated in the "De Anima" the memorable sentence that "man is in a certain measure all things". This idea of man's universal openness runs through the whole of Western thought. It reaches, for example, as far as Marx who, in his "Economic-Philosophical Manuscripts", recognises that man is a generic, universal being, precisely because he can objectify everything, including himself: that is why his activity is free activity. Later, Heidegger will insist that the essence of man is his openness to the understanding of the meaning of being. Man is an "onto-logical animal".

The idea of man's biological unspecialisation - linked to his intelligence - is clearly set out in Thomas Aquinas: "the intellectual soul, being able to understand the universal, has the capacity for infinite acts. That is why nature could not impose on it certain natural appreciations, nor certain means of defence or shelter, as on other animals whose souls have perceptions and Schools determined to particular objects. But in their place man possesses reason and hands, which are the instrument of instruments, since by them he can prepare an infinite variety of utensils for infinite effects"12.

Man's hand is perhaps the most plastic somatic manifestation of his functional unspecialisation. As the anatomists Klatsch and Bolk have emphasised, man - unlike the apes - has an unspecialised hand, which is good for everything in general, precisely because it is good for nothing in particular. The comparison of the hand with intelligence can be traced back to the pre-Socratic thinker Anaxagoras, to whom is attributed the sharp statement that "man is the most intelligent of beings because he has hands". Aristotle expresses it in a symmetrical and less surprising way, but which amounts to the same thing: "man has hands because he is the most intelligent of beings"13. His hand is capable of grasping everything, of having everything. It is a polytechnical organ; but it is, above all, the organ that makes touching possible, the tactile recognition of an object other than one's own body, which is the most elementary level of objectification14.

Even the very rate of growth of the human individual is adapted to this functional unspecialisation. As the anatomist Adolf Portman has pointed out, man is born too early, so that one can speak of a "normalised premature birth". If Portman distinguished between nidicolous animals - those that need a long and intense attendance from their parents - and nidifugous animals - those that immediately fend for themselves - it could be said that man is a "supernidicolous" animal, since his dependence on his parents is very long and his dependence on the social environment is constitutive: he is an essentially social and educable animal. For this reason, its growth period is much longer than that of any other animal (up to 25 years), and, in relation to its somatic Structures , its life average is very long. The human organism needs a long time to incorporate the cultural components of its environment: man is a cultural animal.

Man is both a biological and a biographical animal. Insofar as he is biological, he has an animal nature. Insofar as he is biographical, he has history. To reflect metaphorically this dual condition, Ortega y Gasset once said that man is a centaur. The metaphor - though suggestive - is not entirely apt. For it is not that he has an animal part and a human part - biology and biography, nature and history - superimposed or intertwined. His very nature is human. The body of man is - through and through - a human body.

This peculiar nature of man's biological dimension has been highlighted by the anthropobiologist Arnold Gehlen15 , who has insisted on man's instinctual poverty. It is not that man has no instincts, nor only that he has relatively few: it is that he has something like "unfinished instincts". Ortega - with another, happier metaphor - said that man has "stumps of instincts". Why? Because his biological equipment prescribes neither stereotyped stimuli nor stereotyped responses. That is why we speak of a rupture of his perceptual and effector circuits. This is why man has no "ecological niche". This is why, paradoxically, he can develop ecology as a science and have ecological concerns. Man is never fully adapted to an environment: he has to build his own environment. Life, for him, is not a development but a task.

b) Intelligence and technology in humans and animals

knowledge goal

Biologically speaking, man is - as Gehlen says - a being of deficiencies ("Möngelwesen"). He is a deficient animal, which - in purely biological terms - is unviable. But then, how does the human species survive? And, above all, how does it beat other organisms that are biologically more perfect? Well, by "pulling out all the stops". In the face of his biological penury, man has to turn to a suprabiological resource : to intelligence. The "Australopithecus", which was very well adapted to its environment, inexplicably disappeared without leaving a trace. On the other hand, man, who is constitutively "maladapted", has succeeded biologically thanks to capacities that transcend the biological plane.

Naturally, if man can make use of this resource it is because he has it. What is meant is that in order to survive, man needs to make use of his intelligence, because only in this way is his psychosomatic structure viable.

This has to do with the "rupture" of the perceptual circuit to which we referred earlier. Because of his essential openness to the world, anything can constitute a stimulus for man. Every reality has a meaning for him. And so it happens that he is subjected to such an accumulation of perceptual requirements that he would find himself inundated by them and paralysed, if he could not resort to certain discharge mechanisms, whose intervention is decisive in what we could call the process of objectification16.

In the course of this process, man is exempted or relieved of the requirement to have the totality of the sensitive complexes present at the present time in order to become position of the surrounding environment. By means of the report and the imagination - but above all by means of the intelligence - the experiences that have already taken place are relegated and preserved, so that the subsequent perceptive pictures can be fill in , without the need for them to be present. A hint of light or touch, for example, is enough to complete the constellation of the object. I perceive a shadow and know that someone has passed in front of the window; I hear a thud and realise that a book has fallen to the floor; I run my hand along a metal railing and perceive the dampness of the atmosphere. This is what Gehlen calls the "symbolic structure of perception".

It is true that this symbolic structuring of the perceived already occurs to some extent in various animal species, as "Gestalt" psychology has shown. For example, there are birds that distinguish the configuration or form - the "Gestalt" - of a bird of prey, characterised by its short neck, from that of a stork, characterised by its long neck. But this animal capacity for formalisation is always linked to instinctive behaviour, is reduced to a few perceptual patterns and never transcends the immediacy of the sensible included in a perimonde (even if, as we saw, the stimulus may be topographically distant). All this proves that animals have internal senses: report, imagination, etc. But it does not prove that they have intelligence.

On the other hand, man's capacity for formalisation is vastly superior. We perceive everything according to autonomous "gestalt" configurations, independent of each other. We distinguish one subject of objects from the others, whatever the place in which it appears or the sensible appearance it presents, as long as it maintains its essential structure. The variety and variation of human perceptual Structures is indefinite. If we had only internal and external senses, sensible environments would appear to us as highly complex perceptual mosaics, to which we would be unable to react, because they would have no meaning. If they do, it is because we associate symbols with perceptions. Or, better, because our own perceptions are already symbolic: we constantly associate concepts with images. The concept is also a symbol, but it is no longer perceptual but intellectual.

What does intelligence consist of? In the capacity to make oneself position of reality as such. Faced with a perceptual status such as the one we have just described, man makes use of a completely different function from merely sensing the stimuli coming from the environment: he makes himself position of the stimulating status as a real status and a real stimulation. Stimulation is no longer exhausted in its mere affection of the organism, but, independently of it, it possesses a structure of its own: it is reality. And intelligence is the radical and specific School of man, which gives him the capacity to deal with things as realities. Intelligence refers us to what things are in themselves, before and outside stimulation, in such a way that we are situated in what things are in and of themselves. Xavier Zubiri has developed this conception in an interesting synthesis of data biological and philosophical reflections. The first function of intelligence", Zubiri maintains, "is strictly biological: to become position of the status in order to excogitate an adequate response. But this modest function leaves us installed in the sea of reality in and of itself, whatever its content may be; with which, unlike what happens with the animal, the life of man is not an enclassed life, but constitutively open"17. Man is an animal of realities. This, as we shall see, implies that his intelligence is reflexive, because he can only know objective reality if he knows himself as a subjective reality, distinct from objects.

For example, man sees in water, first of all, a substance to quench his thirst. But since he perceives it as a reality, objectively, he can also grasp it as a means of navigation, or that which can move a mill, or where the moon is reflected. He knows, to some extent, what water is. Although his notion may be refined, he already possesses the concept of water, the intellectual symbol which expresses its essence: what water is in itself.

Technique

This intellectual capacity opens up indefinite perspectives for man, not only for knowledge, but also for action. A simple pebble can be thrown, but it can also be hit against another pebble to build a primitive tool, like those apparently made by "Homo habilis" discovered by Leakey.

Technique is a factual, unquestionable manifestation of human intelligence, but don't some animals also possess a certain skill technique? Surely. But there is an unbridgeable - and observable - gap between animal "technique" and human technique. Bees still make their honeycombs exactly as Pliny described them centuries ago. And no one remembers beavers building their dams in any other way than they do today. On the other hand, human technique is constitutively variable, evolutionary, precisely because man has intelligence, because he grasps things as realities and grasps himself as an active subject.

This relationship of foundation has also been noted by Zubiri: "Man is the only animal that is not enclosed in a specifically determined environment, but is constitutively open to the indefinite horizon of the real world. While the animal does nothing but resolve situations, even constructing small devices, man transcends his present status , and produces artefacts not only made "ad hoc" for a determined status , but, situated in the reality of things, in what they are in themselves, he constructs artefacts, even though he has no need of them in the present status , but for when he comes to have them; he manages things as realities. In a word, while the animal does nothing but resolve his life, man projects his life. That is why his industry is not fixed, it is not mere repetition, but denotes an innovation, the product of an invention, of a progressive and progressive creation. Precisely where the vestiges of tools reveal traces of innovation and creation, prehistory interprets them as rudimentary human characteristics"18.

Intelligence provides man with the School ability to grasp the medium as a medium, precisely because he knows things as objective realities. And this capacity opens up the possibility of actively intervening in them. The object appears as an autonomous "centre" around which perceptions are arranged. And its own constitution can be - to some extent - known. We know that these things belong to a different order from the experiences through which we grasp them. They belong to a real order, goal, different from our own subjectivity, on which we can operate freely. With our own projects, we can capture or modify the constitutive project of realities.

Note that this conception of intelligence also assumes a finalist or teleological vision of reality. If we can act on things and modify them technically, it is because we know their meaning or natural purpose, in which we insert our own ends or goals. Of course, we know our own purposes better than those of things. But this does not mean that physical reality is ateleological. Only by knowing what a stone is and what it is for, can a flint axe be built.

In the face of the materialist and mechanistic ideologies of the last century, the contemporary Philosophy has returned to the question of meaning. And it has been able to see the connection between the meaning of reality and the meaning of human existence. Phenomenology has carried out this task with particular success. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, for example, says: "What defines man is not the capacity to create a second nature - economic, social, cultural - beyond his biological nature; it is rather that of overcoming the given Structures to create others. And this movement is already visible in each of the particular products of the human work (...). For man, the tree-branch-turned-stick will remain precisely a tree-branch-turned-stick, one and the same thing in two different functions, visible to him under a plurality of aspects. This power to choose and to vary the points of view allows him to create instruments, not under the pressure of a de facto status , but for a virtual use and, in particular, to make others with them. The meaning of the human work is thus the recognition, beyond the actual medium, of a world of things visible to each "I" under a plurality of aspects, the taking possession of an indefinite space and time"19.

Thus, the progressive character of human industry has its foundation in intelligence as the capacity to grasp the means-ends relationship, which in turn is based on the conceptualisation of objects as objective realities. Man-made tools are "detached" from the individual corporealised psyche that gave rise to them. It is something stably decanted into the world of things and which can be used, in turn, to intervene more effectively in reality. Thus arises the tool, which is an objectified project of action.

Only man has the capacity to construct these tools in order to make other tools. Khrushchev's experiments - among others - show that the chimpanzee is indeed capable of tool-using and tool-modifying operations, but is unable to carry out real tool-making. The chimpanzee quickly learns to use a stick to bring a banana that he cannot reach with his hand ("tool-using"). If, instead of a stick, the chimp is given a board with clearly marked grooves, but which is too wide to fit through the bars of the cage, the chimp is able to break the board to make a stick out of it ("tool-modifying"). But what it can no longer do, if the wood is too hard to break by hand, is to use a biface axe - or any other instrument - to make a stick out of a board ("tool-making"). What the ape does not "see" - because it is no longer possible to see it, but must be thought - is the transversal or objective relation board-axe-stick: he does not grasp the instrumental mediation, because that is already a conceptual construct.

c) Human language and speech animal

Human language

In the process of objectification, which is characteristic of human behaviour, language plays a decisive role.

Language is an indispensable unloading function. When we designate things with words, we are relieved of having the corresponding perceptual Structures present: when I say "table" I am relieved of the need to have a table sensibly present in order to use it (not to eat, of course, but in a speech or in a reasoning). If we did not enjoy this linguistic function of unloading, we would have to bear an excessive burden. Something like what Jonathan Swift imagined in one of the "countries" he fantastically visited: to prevent the citizens' throats from being worn out, the government had forbidden the utterance of vocal sounds, so that those poor people had to walk around all day with a sack on their backs from which they extracted the objects they needed to refer to in each case. In short, human life would be impossible without the expressive, meaningful and communicative functions of language.

The sound of words has the extraordinary property of being, simultaneously, a movement coming from the subject, and - insofar as audible - a component of the external world, of the world of perception. As Wilhelm von Humboldt said, "man surrounds himself with a world of sounds in order to embrace and make up a world of objects". By means of language, it is possible to address the objective thing almost effortlessly and, at the same time, to perceive it. Insofar as the sound addresses the stimulus, it itself creates the linguistic symbol that is easily linked to that stimulus; so that, when the sound is given, it is as if the thing seen were given, even if it is not present. This makes possible a creative attention with things, since linguistic symbols can be combined in a different way than perceptual Structures are combined20. Different perspectives can be taken on the same thing (the word "idea", from the Greek "eidos", originally means aspect, perspective).

Moreover, language constitutes the factor of "socialisation" of the perceived world. The goal is also intersubjective, accessible to all. This connection between language and society is significant: Aristotle proposed two definitions of man, as a "speaking animal" and as a "political animal". Thus, between man and the brute reality, a kind of "intermediate world" emerges, symbolic and social, which allows speech and work to be shared. The world in which man really lives is not a natural world, but a cultural world: a human world. Never - and less and less - has man lived in pure nature; and nature itself acquires a cultural character, since it has a meaning for human life insofar as it is the object of his activities (or of his contemplation, or of his conservation). The ecological attitude - although superficially it may seem otherwise - is a clear manifestation of this culture of nature. Incidentally, the emergence of ecology has a spocal nature; it marks the beginning of a new epoch, in which nature is no longer considered only as a "material" of work, but as something that has value in itself, meaning, purpose.

speech animal

But let us return to the question of language. So far we have budget that it is a capacity exclusive to man, through which his intelligence manifests itself. But it is not at all clear that there is no such thing as an animal language, and it seems, therefore, that it is not possible to exclude that animals have a certain human-like intelligence. If this were so, the distinction between man and animal would not be essential, but gradual; and man could have arisen, by evolution, from other animal species.

To begin this discussion, it will be good to recall the work of the great Russian researcher Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (1849-1936). Pavlov has gone down in the history of physiology for his theory of conditioned reflexes. He observed that, together with the congenital or unconditioned secretory reflexes, by direct excitation of the desired food, he could create conditioned reflexes if he made some optical, acoustic or tactile stimulus, in itself indifferent, precede ingestion, but whose repeated association made it as active as the original excitatory stimulus. Pavlov thus discovered that, in animal life, a system of signals functions. But, in addition to this first system, which is given by sensitive signs that condition a physiological reflex, Pavlov recognises the existence of a second system of signals, constituted by linguistic signs, that is to say, by words. What emerges from his experiments is that animals do not react to the stimuli of this second system of signals21.

Pavlov discovers the cause of this lack of reaction in the anthropoid's inability to form a general or abstract idea of things. And he proves it with an ingenious experiment. In the centre of a lake there is a large raft on which an ape lives for some time. Between the place where the ape stands on the raft and the place where it is provided with food, there is a device that produces fire, so that it is prevented from reaching the food. There is also a water tank and a bucket. The ape soon learns to draw water from the water tank with the bucket, extinguish the fire and reach the food. On the other hand, it has become accustomed to cooling itself with the water from the lake, when it is very hot. Now, at a certain point, the water is removed from the tank. What does the ape do? He keeps putting the pot in the tank without water, but he does not think of using the lake water to extinguish the fire so that he can have access to the food. Why? Pavlov's literal answer: "It can be seen that he has no general, abstract idea of water as such; at the level at which anthropoids are situated the abstraction of the specific properties of objects has not yet taken place.

Generalising this and other experiments, Pavlov formulates his theory of the four phases of knowledge. We already know the first: it is the training of conditioned reflexes. The second phase is the generalisation of the conditioned reflex, by mere association of sensitive similarities, forming a more or less confused sensitive image. The third is the differentiation of individual peculiarities. And the fourth phase, finally, is the true generalisation, the true abstraction, which consists in freeing oneself from the merely sensitive. Only man is capable of the latter.

What is most interesting in this theory is the distinction and the relationship Pavlov draws between the various phases. The ape is capable of grasping individual differences (third phase) and of a certain generalisation, which is rather a pseudo-generalisation (second phase). But what happens is that, if he grasps the commonality, it is at the cost of not grasping individual differences; and, if he perceives these differences, it is at the cost of not appreciating the commonality. The first of these inadequacies is demonstrated by another of Pavlov's most famous experiments: an ape is trained to build a pyramid of cubic boxes, so that, climbing it, he can reach a fruit placed at the top of the cage; but if the fruit is placed outside the cage, the anthropoid continues to build his pyramids, even though they are of no use to him in reaching the fruit placed outside the bars: he does not see the differences between one case and the other. The second inadequacy is illustrated by the experiment described above: the ape does not grasp the commonality between the water in the tank and the water in the lake. The characteristic feature of true abstraction (fourth phase) is that it grasps the commonality while still seeing the individual differences. Pavlov connects - experientially - with the philosophical theory of the knowledge of universals. According to this theory, the universal, the common, connotes the inferior, i.e. the particular cases. The abstraction does not consist in completely disregarding the individual differences between the individual cases. This is very important for the political Philosophy , because it is necessary to keep in mind both what all men have in common and what each of them possesses that is unique and unrepeatable. The commonality - human nature - is the basis of the essential equality of all men, by virtue of which they all possess the same human rights. But, in addition, each man enjoys freedom staff and an individuality that is not interchangeable with that of another. This capacity to grasp both the common and the individual is proper and exclusive to intellectual abstraction, which only man enjoys. That is why only man alone can, strictly speaking, speak.

But, it might be objected, since Pavlov made his famous experiments, much has happened in the field of biology, and especially in that of ethology. It seems that, more recently, other experiments have come to support the idea that the linguistic capacity of apes is much higher than had been supposed, to the point of being essentially indistinguishable from that of humans.

It should be borne in mind that most of these experiments have been conducted in a human environment. Apes have been made to live in a human environment - a family environment, even - since birth, subjecting them to an intense learning process that is artificial for them. For a start, it should be noted that - given their anatomical characteristics - apes cannot pronounce words: their presumed language is not board member . But they can learn to use various signs - optical, tactile or acoustic - corresponding to words and construct sentences by combining these signs; they even invent other sentences that have not been taught to them, in order to get what they want.

Allen and Béatrice Gardner famously started teaching Ameslan - a language for the deaf and dumb - to the 10-month-old female chimpanzee Washoe in 196622 . Washoe was eventually able to learn a considerable issue number of signs, some 130, relating them to corresponding objects. She also gave correct answers to questions such as subject "where?", "who?". With this method it cannot be ascertained whether the animal has mastered the syntax, as it is only taught to relate the object to a conventional image, to a gesture.

David Premack's work with Sarah, a female chimpanzee, was a further step forward23. The system chosen for speech consisted of manipulating plastic cut-outs of different shapes and colours on a magnetic board, which were made to correspond to various English words. Sarah was able to select - for example, from among "sugar", "banana" and "apple" - the sign corresponding to what she wanted to eat. She was also able to compose simple sentences of four to seven signs to express wishes or ask questions. He even seemed to understand the use of quantifying words - such as "all", "several", "none" - and the use of the copula "is" as a connective between subject and predicate. Most importantly, he was able to establish conditional connections of subject "if... then...". (if ...then...).

More complicated research has followed, including the "project Lana"24. Using a computer, words appear on the screen when the corresponding key is pressed. Lana was able to use a vocabulary of 75 words, ask questions about the name of something and make meaningful connections from subject "if... then...". Lana also showed some linguistic creativity, to the extent that in a period of two months she discovered 174 new linguistic sequences, which were related to objects in her environment. However, Lana's overall success rate was less than 76.6%.

It was not possible to demonstrate that the chimpanzee Lana had true representational ability, and of course the influence of skill and the enthusiasm of his trainers was decisive25. On the other hand, because a reduced issue of signs is used, allowing only certain combinations, the hit rate may not be entirely significant.

Nor is it possible, for the moment, to discern to what extent this taught language responds to the natural capacities of the ape or is a simulation of the behaviour of its trainers. The methodological problem that arises here is similar to the one that arises with respect to the problem of whether digital computers think or can think: it is the very interesting question of Artificial Intelligence. Well, as the analytical philosopher John Searle26 has shown, it is possible - and already partially possible - to build computers whose programmes allow them to behave as if they were thinking; but this in no way means that they really think. For a fundamental reason: because the computer program - based on the combination of very numerous 1/0 alternatives - is exclusively syntactic in nature, but in no way semantic in nature; that is, the sequences allowed by a digital computer program - however perfect it may be - do not contain meaningful content (semantics), but only combine sequences of meaningless signs (syntax). This is equivalent to saying that, although the computer is capable of using language English, it does not understand English, i.e. it knows nothing of what is said in English. Searle gives a graphic example: I can be locked in a room with the thousands of signs that make up the Chinese language in boxes, and be so well "programmed" that I know how to combine the corresponding signs in such a way as to produce Chinese sentences; and even respond with combinations of this subject to sets of signs - questions - that someone enters from outside the room. But despite all this, I don't understand Chinese, I don't know what is meant. I have learned to use a few signs, and nothing more.

Perhaps some of this will happen to domesticated chimpanzees. Presumably, if they really have linguistic abilities, they will use them in their natural or "wild" life. By observing them in the wild, it will be possible to see what they are naturally capable of.

In a recent article27, Jean Pierre Gautier and Bertrand Deputte describe their work on analysing the sound signals of apes. These signals are recorded graphically in order to determine the average physical characteristics and the limits of variability of the recorded cries. In this way, they have compiled what is traditionally called a "repertoire", i.e. a list of the different sound signals emitted by members of a species, according to their age and sex. In this way it is possible to see how individuals use - partially or completely - the repertoire. As far as they have been able to observe, cries are highly specialised and genetically determined. Over time, the animal learns to associate them with events in its biological context. The different sounds indicate alarm, location of members of group, aggression, etc., and can distinguish whether they are emitted by a young individual or an adult. Moreover, the system of speech is cross-modal: besides sounds, visual, tactile and olfactory signals are also used.

In any case, these signals are strictly determined, are linked to the immediate biological environment and have - at final- many of the characteristics of what we have described as instinctive behaviour. Michael P. Ghilieri's study on the speech of chimpanzees in their natural environment28 is very interesting in this respect.

Jean-Pierre Gautier has shown how the language of apes is exhausted in a very specialised repertoire. Some species have only ten or so basic cries, while in others, the repertoire is made up of fifteen to twenty basic cries, which are always genetically determined, even if their use is updated by learning. Moreover, the use of these signs is modulated by sex, age, and "status" on group. Another very important finding is that, in apes, verbal behaviour depends on sub-cortical brain areas. The very weak involvement of the neocortex means that apes cannot exert voluntary control over their expression board member .

One of the manifestations of cooperative behaviour in male chimpanzees is the vocal signals known as "ululating sighs", which comprise stereotyped sounds: screeches, cries, groans and roars, audible up to two kilometres away in the wild. They can be emitted by a solitary ape or by a chorus of chimpanzees at group . Chimpanzees hoot more when moving, approaching a food source , distinguishing other chimpanzees or responding to another chimpanzee's call group. More than half of the recorded cries are part of a exchange with other anthropoids. When analysing sonograms of ululating sighs, enough signals are found in each call to distinguish the individuals emitting them: when a group launches its cries through the forest, it communicates the identity of the members of the group, their issue and location. The most important function of the ululating sigh is to alert other members of the community to the presence of fruit. It is therefore a speech closely linked to immediate biological interests. Its resemblance to human language is very distant.

Let us now return to a capacity of animal "language" to which we alluded earlier. This is the ability to grasp and express the if-then relationship in some way. Some trained chimpanzees have shown that they are able to establish this relationship. The experiment consists of presenting them with three different sequences: a whole apple and a split apple; a dry sponge and a soaked sponge; a white sheet of paper and a smudged sheet of paper. If the animal associates, for example, a knife with apples, this means that it has the logical if-then relationship: If the apple is whole and then split, then it has been cut with the knife.

However, this does not mean that animals have a causal knowledge , as some of the authors we have just quoted suppose. It must be borne in mind that the logical relation expressed by "if-then" is different from that expressed by "because". In the first case, it is enough to know that from one state of affairs follows another; but it is not necessary to know the reason why it follows. A causal relation is not expressed, but only a conditional relation. On the other hand, when a properly causal relation is expressed, the reason why one event follows another is known29.

It seems to be a nuanced difference, a subtle logical distinction. But it is much more than this. What happens here is similar to what we said about the difference between the digital computer and human intelligence. However perfect the computer may be, it does not go beyond the level of syntax, of the sequence of "bits", without reaching the level of semantics. From the point of view of knowledge, an animal - however elementary it may be - is superior to a computer. An animal really knows, something that a machine will never achieve. Moreover, the "language" of anthropoids reveals that they reach the semantic plane; that they somehow know what a sign refers to. But the semantics of animal language is only extensional and never becomes propositional or intensional: it signifies the set of particular cases (extension), but not the common quality or reason (intension). To realise what the intensional adds to the extensional, it is enough to think of the difference between "to know" and "to know" (which also occurs in other languages: "wissen" and "erkennen" in German; "savoir" and "connaitre" in French). For example, you can say at Spanish "I know you", but you cannot say "I know you". On the other hand, we say "I know that John is intelligent", and not "I know that John is intelligent". It is precisely in this subject of sentences with "que" followed by a proposition that what is meant by intensional or propositional is most clearly revealed. The current analytical Philosophy of language has developed a complete theory of propositional attitudes, which are manifested in verbs such as "to believe", "to know", "to doubt", "to want", "to suspect"... followed by the conjunction que and a completive sentence. Note that the use of these verbs expresses a reflexive attitude, which is absent from the meaningful and expressive functions of purely extensional language. With intensional language we do not refer directly to a thing, but to a proposition, a "logos", a "ratio", a reason. We reach a level of abstract content, which is absent on the purely extensional semantic plane, and which is required in order to know a why, a reason why one event gives rise to another.

The generalisations or associations that animal language reveals - even the if-then relation - do not transcend Pavlov's second or third phase. In contrast, human language shows that the fourth phase, the abstract and reflective level of intensional semantics, has been reached. Mathematical logic shows us that the intensional speech is irreducible to the extensional. But it would be long and complicated to explain it. In our subject, it is enough to understand the difference between what it means to "make sentences" or to judge for an animal and for a human being. Certainly, animals judge in some way. Aristotle had already attributed this ability to them, which is the responsibility of a School which he called estimative. Animals are able to "judge" whether something is pleasant or unpleasant, beneficial or harmful. But they are not able to judge about their judgement, which implies a reflexive dimension, which is the characteristic of human language. Animals know, but do not know; they want, but do not want to want. They are not capable of abstracting, of forming real concepts, but they move between more or less general or schematic images. And, for this very reason, they are not capable of reflection. None of the features of animal language described by ethologists show that they possess true abstraction or reflection, that they are capable of orienting their behaviour towards reasons or meaningful intellectual content.

Nietzsche recounted this status, in the form of an apologue, in his "Untimely Considerations": "Once man asked the animal: Why (reason!) do you not speak to me of your happiness, but stand there staring at me? The animal wanted to speak and answered: the reason is that whenever I want to speak I immediately forget what I wanted to say. But he immediately forgot his answer and remained silent? And so the man continued to wonder why the animal did not speak".

d) Mind and body

Freedom

The irreducibility of intelligence to the organic subject , of mind to body, is especially clear in the sphere of freedom.

There is no doubt that higher animals enjoy a certain freedom, as manifested in their curious or exploratory behaviour. In a certain sense, they do what they want, they have freedom of action, within the framework of their world. But that is not what we properly call freedom, for example in the political field. Human freedom is, before freedom of action, freedom of decision, freedom of will.

The will is the School that is not restricted to the alternative of the pleasant versus the unpleasant, but can decide against the pleasant and in favour of the unpleasant, when the latter is considered under the aspect of the objectively good. In other words, the will is the School that does not decide between the pleasant and the unpleasant - in which case the choice is made beforehand, biologically - but decides between the good and the bad. But when we speak of "good" and "bad", we are already moving on an intellectual level that demands a justification, a reason, which is given by the intensional particle "because", as we saw in section above.

We know that animals themselves overcome in their behaviour the outline stimulus-response, that they can reach more or less stable imaginative configurations. But, in any case, they always move - "choose"- by reference letter to material things, not on the basis of reasons expressible in intentional language. The animal cannot adopt what we called "propositional attitudes". Properly speaking, it does not know, doubt or want, because these attitudes do not refer to spatio-temporal things, but to propositional contents introduced by the particle that. If anything, the animal wants something, in the sense that it desires it, but it never wants that... whatever it is. Among other things, and above all, it never wants to want. The "will to will" indicates the reflexivity enjoyed by the human will, which cannot properly will anything, but only that which is justifiable with a reason: "I will because...". That is why man can self-determine and the animal cannot.

As we have seen before, the animal can "judge", evaluate what is useful or harmful, but it cannot judge about its own judgement, to approve or disapprove it from the point of view of the good goal. The reflexive structure characteristic of human intelligence is also characteristic of freedom.

It is true that the animal can learn by the procedure of "essay and error". But even if it detects a previous error, this phenomenon is completely different from what, in man, we call "responsibility". The animal is not manager responsible for what it does, because its action is not reflexive, since it is not self-determined. That is why an animal, as a learning procedure , can be rewarded or punished; but it cannot be praised or reproached for something it has done. Only man is worthy of praise or reproach.

Human freedom has, we said, a reflexive structure. This observation is perfectly consistent with everything we have been pointing out so far. Because, throughout these pages, we have insisted, above all, on the fact that what is perceived by man acquires the category of object, of something that is of itself, that has in itself - in its reality - the law of its consistency: that is why man can grasp reasons, say that... and because..., and express all this in a language that is not purely constatative or extensional, but that refers to meaning - to logos - and is therefore intensional.

The world of man - unlike the animal world, which is inextricably linked to the organism - has an autonomous nature: it is in itself what it really is. But, as Landmann30 points out, this autonomous position of the world as a universe goal does not fail to have an effect on man's position within the world as well. With his understanding of the world, his understanding of himself is transformed. He too becomes "goal", together with the world, albeit in a very different way, which consists in being a subject. To be a subject is to contemplate oneself from the world, as a reality irreducible to the world. To be a subject is to be autonomous in a completely different way from that in which we say that the world is autonomous. The human world is autonomous because it is a real object, in itself, distinct from man; man is autonomous, not only because he is in turn distinct from the world, but also because he knows himself to be distinct, and because this knowledge translates into a free action, into a decision.

This peculiar status has been aptly named by the anthropologist Helmuth Plessner as the eccentric position of man31. The animal perceives everything from itself and sees it only in its own perspective, from which it is established in advance what is pleasant or unpleasant, useful or harmful, depending on whether or not it responds to the momentary biological interests of the individual or to the more stable interests of the species. The animal is ineluctably bound to the here and now of its own status. It is, simultaneously and inseparably, its own vital centre and that of its perimonde.

Man, on the other hand, lives eccentrically. He does not only orientate the world towards himself, but he also orientates himself towards the world, he implants himself in it; and from it he is able to freely establish his own position. Man's life is eccentric. Because he is bodily, he also lives in a biological environment, but he breaks through it, surpasses it and transforms it. Man therefore has the capacity to distance himself from himself and to experience himself as a subject. He can know himself and make up his own mind: he is reflective and free. And, to that extent, he cannot be an exclusively bodily being. Something in him transcends his own body. We call that which is not identified with the body the mind.

On the one hand, the dualistic error must be avoided. The mind is not something other than the body. In reality, that which we call "mind", "psyche" or "soul", is not a thing. Man's subjectivity is worldly. For man himself is embedded in the world, but no longer as the fish is in the river or the chimpanzee in the jungle, but is in the world, knowing it and knowing himself in it and from it. There is no experience of self without worldly context. Anything else would be an idealistic "angelism".

Now, that very objective presence of things before the human mind, and above all the very reflective presence of the mind before itself, reveal that man is not just another thing among things. Man is worldly - "being-in-the-world" (Heidegger) - but he is not unworldly. We must reject the dualism that understands mind and body as two things (the one thinking, the other extensive, as Descartes intended). But neither is materialistic monism admissible, for which, in final, both objectivity and mind are reduced to their physical components. In this physicalism, specifically mental phenomena are marginalised or reduced to epiphenomena of bodily processes. Every behavioural process is sought to be explained in terms of physical cause or conditioner-conditionedness. But this is "achieved" only at the price of a radical impoverishment of human reality; and at the cost of many incoherencies and pseudo-explanations, denounced by contemporary anthropology. Mechanistic materialism cannot even get an idea of what the mind-object relation means. The original phenomenon of human objectivity - which, as we have seen, does not occur in animal behaviour - is irreducible to the influence of a material agent on a biological organism. The mere physical influence provokes a physiological modification, but it is not enough to justify the mental experience that has the object -from which the stimulus originates- as topic. It is this thematic presence - of a meaning goal, of a real reason, of a meaningful content - that completely escapes materialist analysis. Much less can the reflective presence of the mind before itself enter into it.

There is only true objectivity for a mind that is capable of knowing itself, i.e. for a consciousness. An organism without reflective consciousness is not capable of distinguishing itself from its environment. On the other hand, an organism with reflective consciousness - such as man - can operate autonomously in the world, without being inescapably subject to an instinctive patron saint of behaviour or to mere responses to the biologically relevant configurations of the environment. That is why man is free.

But is it really, and is it not more true that we too are subject, no longer to simple biological pressures, but to psychological or social pressures to which we in fact always react in a way that could have been foreseen beforehand? We are not going to enter fully into this controversy, as long as Philosophy itself, which pits determinism against the recognition of freedom. And we do not enter into the discussion for two reasons: first, because we do not have the time; and second, because we do not need to. Although this second and decisive reason may seem pretentious, it is nonetheless valid. As Jaspers said, the best - and, in a way, the only one - test of the existence of freedom is myself, who wants it. Who does not want to be free? Sometimes we think that we would prefer not to be, precisely because of the responsibilities that come with having to decide. But even then, what we would like is to have the "advantages" of freedom without the "disadvantages" of responsibility. And that is what, given the human condition, cannot be. Human freedom is honour and burden, "honor et onus". However, any one of us can say in all sincerity: "I want to be free". Well, that is already a test of freedom, because only a being who is already free can want to be free. The will to be free is a free will that expresses itself reflexively (in typically intensional language).

Mental acts, expressed by a verb of knowledge or volition in the first person of the present indicative, are indubitable. Because in them there is no mediation or interference that could mislead us. If I say (sincerely, of course): "I am sad", there is no doubt that I am sad. If I say: "I am suffering", no one can prove me otherwise. It is particularly annoying for anyone to have someone - his mother, for example - try to convince him that his teeth don't really hurt, when he knows they do. No one can meaningfully say: "I don't know if I'm in pain". Much less: "I don't know if I think". Except in borderline cases, it is also impossible to say: "I don't know if I want to" (the borderline, but very real, case is: "I don't know if I love you"; that is, I don't know if I love you enough to, for example, marry you). Well, the same goes for the expression: "I decide". If I know that I am deciding freely, I cannot fool myself: I am free. At least I am at that moment, which is the same as just being free.

Naturally, there is room for a multitude of clarifications here, which do not, however, invalidate the certainty of this original experience of freedom. Psychology and sociology have uncovered many conditioning factors of which we are rarely aware. But that, in any case, would prove that we are less free - or that we are free in a different way - than we thought. But free we are. One can "reify" oneself, strangle one's life to the point of almost animalising it. But freedom has invulnerable limits that cannot be destroyed. Which is a paradox: we have to be free, we are obliged to be free.

The autoknowledge

Free action is rational action. Therefore, when we act freely, we act for motives, for reasons. And, logically, we decide for the reason that seems to us to be the strongest. But this does not abolish freedom either. Because the influence of reasons is not a mechanical causality. If anything, it is a "causality by sense" which, far from excluding freedom, demands it.

When I am in the process of deciding, what I have before me are various possibilities of action, which I evaluate and compare, in the light of the motives or reasons that support the different options. When I decide, I confer on one of these possibilities the status of a project: I take it out of its ideal world and commit myself to realise it. The important thing to note here is that, in making a decision, I am not only deciding on one of these possibilities. What is decisive, so to speak, is that I decide. The decision about a possibility of action is, radically, a self-determination. I am the one who gives this possibility the nature of my project. And this is something that, in the last analysis, is not imposed on me by the reasons that support that possibility. In fact, I often decide for possibilities that are objectively less strong, but that are better integrated in my vital project , in my preferences or pretensions. And those same pretensions are not compulsive, because they are not really tensions, impulses that - as in animal life - trigger me towards something. They are pre-tensions, pre-tensions that require voluntary choice to become decisions.

The important thing, we were saying, is to bear in mind that, in deciding, I decide. This reflexive pronoun - "me"- is a linguistic expression of the reflexive structure of freedom. In deciding to decide, I appear myself. In freedom, the I appears.

And this, in turn, is only possible because of the reflective structure of human intelligence. Certainly, we are not a pure consciousness, our being is not exhausted in the self. This is what Ortega's famous saying expresses: "I am me and my circumstances". It is also true that we know ourselves very little, and that only Don Quixote, in his madness, could say: "I know who I am". But, for better or worse, we know each other. And we can begin many sentences - perhaps too many - in this way: "I... whatever".

The self is the core of what we call "mind". All mental states refer, in one way or another, to the self. These mental states - knowledge, volitions, beliefs, feelings - are bound to a body, but they are not reduced to bodily states. Bodily states are physical states and therefore situated in space and time. On the other hand, mental states are not, in themselves, spatio-temporal. I can say: "in such and such a place, on such and such a day and at such and such a time, I understood Bernoulli's theorem". But that theorem has nothing to do with that place and that time; nor does my understanding of the theorem. For example, it would make no sense to say that I understand the theorem on even days, but not on odd days; or on this bank of the river Sadar, but not on that bank. The intellectual knowledge , in itself considered, has nothing to do with space or time. How long does a thought last? The answer is: "as long as a thought lasts"; an expression that in everyday language means: nothing. A thought has no duration, no extension, no weight, no colour. My concept of "green" is not green. And so it is with volitions. Let us go back to what we considered before as a borderline case - "I love you" - and suppose it is said in a sincere and resolute way. However borderline the case may be, the person to whom the sentence is addressed would do well not to admit restrictive clauses of subject "here" or "today". Strictly speaking, it makes no sense to say: "I love you here" (but not where I am doing my military service); or "I love you today" (but I don't know what will happen tomorrow). Loving another person has no spatio-temporal limitations, precisely because it is something - a state of mind, however prosaic it may be - that has, in itself, nothing to do with space or time. It is not, therefore, a physical state: it is not something material.

This characteristic of mental states refers, in final, to the awareness of one's own identity. I know myself as something - someone - that is not subsumed in space and time. I am the same now and then, here and there. My self is not spatially localisable: it is not in one place in the body, but is all of it in each and every part of the body. As the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein pointed out, when I say "my foot hurts", I do not mean that it is the foot that hurts, but that it hurts me (in the foot). This subject of the presence of the mind in the body excludes that it is something material: it is not something like a very subtle subject , or an energy field, nor can it be explained by resorting to nerve terminals.

Material things have a diffluence of parts: "partes extra partes", parts out of parts, as the scholastics used to say. The subject is never punctually concentrated but, in one way or another, dispersed. On the other hand, the I has the capacity to have itself in an absolutely "concentrated" and punctual way. In knowing myself, it is I - the whole of me - that possesses - the whole of me - myself. It is as if I concentrate myself completely on one point. But it is something else: it is that I relate to myself - I have or possess myself - in a materially inexplicable way.

A body acts only on another body or on another part of it. The self, on the other hand, relates strictly to itself by self-knowing. This self-knowledge is an action that has its own end in itself, that does not "go outside itself", as is the case with all physical actions. It is not spatio-temporally detached.

That is why the human mind is able to measure cosmic events, as if it were outside them. If man can do physical or mathematical science, it is because he can mentally embrace all possible space and all possible time. He can conceive of "empty" space and time as pure duration. This is a clear sign that he himself is not entirely immersed in space and time. The capacity for true abstraction - Pavlov's fourth phase - would not be possible if the mind were simply a materially individual thing. If man is able to grasp ontological aspects of reality - ideas or concepts - that transcend space and time, it is because his mind transcends space and time, and thus subject.