You may be interested in:

A biological theory of freedom

Author: Juan Arana(jarana@us.es), Full Professor de Philosophy of the University of Seville

Published in: Civica

Publication date: 2018

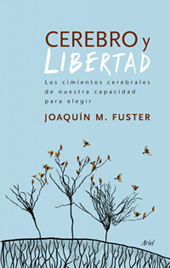

review of the book Cerebro y libertad. Los cimientos cerebrales de nuestra capacidad para elegir, by Joaquín M. Fuster (Barcelona, Ariel, 2016. 375 pp.)

Joaquín Fuster's book prolongs a tradition that does honour to Spanish culture: that of the physician-humanists, a tradition that we could trace back, who knows whether it goes as far as Averroes and which, passing through Huarte de San Juan, would resurge in the 19th century with Letamendi and Nieto Serrano and, in the 20th century, with such exalted names as Ramón y Cajal, Marañón, Laín Entralgo, Rof Carballo, López Ibor and more recently Vallejo Nájera and Diego Gracia. Lately there has been the impression that his momentum was waning, but books such as the one we have before us today renew confidence that this is not the case. Fuster combines his exceptional quality and prestige as a scientist with great culture and sensitivity as a humanist, reflected, for example, in his brilliant commentary on the last movement of Brahms' fourth symphony (pp. 219-221). Moreover, he is extraordinarily courageous, as he tackles a thorny and conflictive topic : the relationship between the brain and freedom. Fuster is no stranger to the important consequences it has in the field of individual and social life, as well as in ethics and politics, and even in culture, art and creation. That is why he devotes the second half of the book to analysing the impact of the problem in all these areas. This part becomes a hymn in defence of democracy and tolerance. There are many of us, of course, who share a belief in these values and a firm determination to promote them. But when the defence comes from an artist, a writer or a philosopher, it does not have the same scope as when it is made by a distinguished neuroscientist. The difference is that today neuroscience is a pillar of civilisation. It is the science of the moment. Society is pinning its hopes on it, governments are competing to protect it, and the budgets of public agencies are looking at it with great care because, at final, they are all vying for its favour. All are declaring that this will be the year, the decade or the century of the brain. The unveiling of its mysteries occupies in the collective imagination the place previously reserved for the deciphering of the genome or the conquest of the moon. The issue of young people who devote themselves to studying it has grown exponentially and the discoveries they bring with them are piling up in prestigious journals and grabbing the headlines of the news. In these conditions it is difficult to escape the temptation to intellectual arrogance and arrogance. The fact that barriers are falling and enigmas are being dissipated gives rise to the belief in many that no obstacle can be overcome and no question remains unanswered. Something similar has happened in the past with other sciences: mechanics, electromagnetic theory, organic Chemistry , evolutionary biology and later molecular biology all raised hopes that they would eventually quench all human thirst for knowledge and dispense all the graces our species craves. Even smaller theoretical projects, such as Durkheim's sociology, Freud's psychoanalysis, Skinner's behaviourism, or the structuralism of Lévi-Strauss, Foucault or Lacan had their moment of glory and conceived pretensions of despotic domination over all branches of knowledge and action.

Joaquín Fuster's book prolongs a tradition that does honour to Spanish culture: that of the physician-humanists, a tradition that we could trace back, who knows whether it goes as far as Averroes and which, passing through Huarte de San Juan, would resurge in the 19th century with Letamendi and Nieto Serrano and, in the 20th century, with such exalted names as Ramón y Cajal, Marañón, Laín Entralgo, Rof Carballo, López Ibor and more recently Vallejo Nájera and Diego Gracia. Lately there has been the impression that his momentum was waning, but books such as the one we have before us today renew confidence that this is not the case. Fuster combines his exceptional quality and prestige as a scientist with great culture and sensitivity as a humanist, reflected, for example, in his brilliant commentary on the last movement of Brahms' fourth symphony (pp. 219-221). Moreover, he is extraordinarily courageous, as he tackles a thorny and conflictive topic : the relationship between the brain and freedom. Fuster is no stranger to the important consequences it has in the field of individual and social life, as well as in ethics and politics, and even in culture, art and creation. That is why he devotes the second half of the book to analysing the impact of the problem in all these areas. This part becomes a hymn in defence of democracy and tolerance. There are many of us, of course, who share a belief in these values and a firm determination to promote them. But when the defence comes from an artist, a writer or a philosopher, it does not have the same scope as when it is made by a distinguished neuroscientist. The difference is that today neuroscience is a pillar of civilisation. It is the science of the moment. Society is pinning its hopes on it, governments are competing to protect it, and the budgets of public agencies are looking at it with great care because, at final, they are all vying for its favour. All are declaring that this will be the year, the decade or the century of the brain. The unveiling of its mysteries occupies in the collective imagination the place previously reserved for the deciphering of the genome or the conquest of the moon. The issue of young people who devote themselves to studying it has grown exponentially and the discoveries they bring with them are piling up in prestigious journals and grabbing the headlines of the news. In these conditions it is difficult to escape the temptation to intellectual arrogance and arrogance. The fact that barriers are falling and enigmas are being dissipated gives rise to the belief in many that no obstacle can be overcome and no question remains unanswered. Something similar has happened in the past with other sciences: mechanics, electromagnetic theory, organic Chemistry , evolutionary biology and later molecular biology all raised hopes that they would eventually quench all human thirst for knowledge and dispense all the graces our species craves. Even smaller theoretical projects, such as Durkheim's sociology, Freud's psychoanalysis, Skinner's behaviourism, or the structuralism of Lévi-Strauss, Foucault or Lacan had their moment of glory and conceived pretensions of despotic domination over all branches of knowledge and action.

It is understandable, then, that leading representatives of neuroscience, together with scientists from other branches attracted by it, equally motivated philosophers and communicators who do not want to be left behind, are unashamedly throwing all the bells into the air. Examples of the first group include the book The Brain and the Myth of the Self by Rodolfo Llinás; of the second, The Scientific Search for the Soul by Francis Crick; of the third, Consciousness Explained by Daniel Dennett; of the fourth, The Soul is in the Brain by Eduardo Punset. Nevertheless, there were and still are neuroscientists reluctant to extrapolate their conclusions happily, forgetting the precautions that the scientific method prescribes. The figures of Sherrington, Penfield or Sperry himself in past generations, and Benjamin Libet or Giacomo Rizzolatti in the most recent, show restraint in the face of the excessive confidence and (depending on how you look at it) optimism of the Edelmans, Tononi, Changeux, Ramachandran, Damasio, Koch, Goldberg, etc.

Those who claim that neuroscience is or will be a dispenser of definitive truths about man tend to underestimate the evidence that the comprehensibility of reality is limited, as other more established creations of research, such as quantum mechanics or the dynamics of complex systems, have found. Many authors prefer to ignore this evidence, with the excuse that, as Dennett graphically expresses: "in the brain, quantum effects and indeterminacies cancel out". Rubia is another of those who think that the physico-chemical theories that were in force at the end of the 19th century, when determinism had not yet been abandoned, are enough to investigate the brain. It is clear that Joaquín Fuster does not engage in such confident, not to say careless, procedures. The clock of his physics is set and he takes good account grade of what we might call the "intrinsic limits" of the natural understanding of the world, including the brain:

Those who claim that neuroscience is or will be a dispenser of definitive truths about man tend to underestimate the evidence that the comprehensibility of reality is limited, as other more established creations of research, such as quantum mechanics or the dynamics of complex systems, have found. Many authors prefer to ignore this evidence, with the excuse that, as Dennett graphically expresses: "in the brain, quantum effects and indeterminacies cancel out". Rubia is another of those who think that the physico-chemical theories that were in force at the end of the 19th century, when determinism had not yet been abandoned, are enough to investigate the brain. It is clear that Joaquín Fuster does not engage in such confident, not to say careless, procedures. The clock of his physics is set and he takes good account grade of what we might call the "intrinsic limits" of the natural understanding of the world, including the brain:

24 This position is at odds with modern neuroscience for a number of reasons, including complexity, variance, non-linearity and the probabilistic nature of neural transactions, especially with respect to psychological phenomena.

He not only knows and assumes the most recent scientific rationality, but relies precisely on it to outline a model of understanding in which neurological processes and freedom, far from being in conflict, would seem to cooperate. In his own words:

17 However, it is precisely in the crucible of probabilities and uncertainties of the human brain that freedom comes to life. The ability to choose between possibilities comes literally from the variance and the Degrees of freedom of innumerable variables that underlie future human action. As with evolution, determinism and direct causality dissolve into probability and, in doing so, yield to a teleological factor: finality, the goal.

There is, in fact, a clear contrast between the way neural determinism approached the understanding of brain activity and how Fuster does it: neural determinism tried to narrow down causal processes to make them practically linear; a few neurons or nodes would channel decision-making and explain report or consciousness. Fuster, in harmony with the most recent results of the research, emphasises its multi-relational character, stresses that the functions of the mind are distributed in extensive areas not only of the cerebral cortex, but also of underlying Structures rooted in turn in the somatic and cultural environment, which leads him to give new meaning to Ortega's motto "I am I and my circumstance". All of this is a breath of fresh air that contributes to clearing the rarefied atmosphere of naturalism in use. The image he proposes both of the brain and of freedom is more flexible and promising than the one usually found in the literature on the subject published in recent years. Nevertheless, Fuster makes it very clear that his contribution remains attached to the naturalist viewpoint, for, as he repeatedly states:

13 This is not to say that any brain structure, not even the frontal lobe cortex, escapes natural causality or is endowed with the power to choose and decide for us. Quite the contrary: I understand that the dynamics of the frontal lobes are ultimately determined by the genome and the environment. written request .

In this sense, I would say that Fuster is a naturalist, but not a scientism. Scientism implies turning natural science into the supreme written request to settle questions that refer not only to physics, Chemistry or biology, but also to psychology, sociology and in general to any anthropological enquiry. It tends to defend a reductionism that is at least ontological: there are no entities with properties beyond those that science detects and studies. Methodologically, it accepts that the more specialised sciences (such as neuroscience) work with concepts and methods that do not belong to the more encompassing sciences (such as physics), but demands that at least in principle there should be the possibility of redefining and unifying all of them under the latter's sponsorship .

The non-scientific naturalism that I attribute to Fuster leaves aside the dream of a science unified under physicalist standards, but insists that philosophical reflection should tackle the synthesis of all our knowledge without mixing in it ingredients different from those that each of the sciences, from the most universal to the most particular, contemplate.

I have to warn that I do not subscribe to either scientistic or non-scientific naturalism. There are philosophers who oppose naturalism in all areas. I do not claim to speak on their behalf, because I take naturalism to mean both inorganic and living nature. But I argue that in the transition from non-conscious to conscious life there is a categorical leap, which closes the way to an explanation of the latter from the same explanatory principles that serve for the former. I believe that Fuster understands it differently, and that is why he states categorically that consciousness is an exclusively derived reality, a simple epiphenomenon:

44 Conscious experience is by definition a phenomenon, or more accurately an epiphenomenon, in the sense that it simply accompanies the state and functions of the brain. In any case, it does exist, but it lacks characteristics or even operational definition.

What exactly would it consist of then? Let's see what Fuster says:

99 Consciousness is a state or quality of the functional mind that is only present - though operationally not essential - in circumstances of relatively intense mental activity.

De-emphasising consciousness is, of course, a relevant theoretical decision that has important consequences. Although it is not explicitly stated, it amounts to separating it from the things that "are" and placing it alongside those that simply "appear", which is not far from turning it into a mere phantasmagoria. Consciousness also drags with it into exile the "subject", the "I", and any other element that could protect the conjugation of the verb "to act" in the first person. Not in vain, on the other hand, since it is well known that science always adopts a third-person perspective. Fuster's hand does not tremble when it comes to performing this painful surgical operation. The manoeuvre, in principle, threatens the very concept of freedom, since how can one speak of freedom without it being the property of a well-defined agent? But Fuster does not want to challenge the idea, and therein lies the originality of his contribution: to maintain freedom, but without rooting it in the conscience or in the self. Where then? The answer is unequivocal: Fuster transfers ownership of the concept to the brain itself or, more precisely, to the prefrontal cerebral cortex:

125 To understand how information and action decisions are made in this immense relational file that is the human cortex, we have to make two difficult but indispensable changes in our thinking. The first is to transfer the role of the "free voter" from the ego or self to the cerebral cortex. The second is to strip the ego or self of the self-consciousness of its decisions; in other words, to make consciousness largely "optional".

What he proposes in final is nothing less than "a truly biological explanation of human freedom" (268). This places him, within the classifications we philosophers are so fond of, in the group of the compatibilists. Compatibilist at purpose of freedom and epiphenomenalist as far as consciousness is concerned. Compatibilists do not believe that one has to give up explaining human behaviour in terms of natural causality in order to simultaneously attribute freedom to it. They used to be determinists and conceived of freedom as knowledge and assumption of necessity, in the manner of the Stoics and Spinozists. But Fuster, as I have already said, is not a determinist, nor is contemporary science, which long ago gave up the idea of completely determining processes as complex and scarcely univocal as those that take place in the intricate neuronal network that forms the core of the brain. A humanist like me draws from this the consequence that natural causality does not have the exclusive right to determine all the processes that take place in the world in general and in the human brain in particular. Consequently, without the need for homunculi or separate substances, the reality "man" fulfils on the one hand all the requirements and demands of natural causality, without ceasing to be the protagonist in some sense of what happens to him, a feature that emerges at the phenomenal level in the conscious processes of decision. But Fuster does not pretend to speak of this subject of freedom, the existence of which he considers in some passages of his book - and with a certain contemptuous tone - a merely academic question:

276 At this point I trust I have helped the reader to come to the correct conclusion that the controversy about the existence or not of free will, as an absolute "all or nothing", is purely academic, irrelevant to neuroscience.

Thus, he wants to continue to speak of freedom on the level of neuroscience and - if you will forgive the redundancy - to "free" freedom from its enchainment to the conscious "I". This explains why he claims the possibility of considering unconscious mental processes as "free":

125 ...we are not consciously aware of the reasons for much of our behaviour. This is not to say that our behaviour is predetermined and lacking in freedom.

129 ...freedom does not need conscious choices.

150 ...it is generally assumed that free will entails conscience, when this may not be the case.

284 The actions themselves will not originate in consciousness, but the other way round. The agent will be the cortex, and the consciousness will be a by-product of the action.

It is customary to associate conscience and freedom to the point of exonerating from any ethical or penal responsibility the acts that one may have committed unconsciously. Why? Because it is assumed that by becoming self-aware we take ownership of our behaviour and being. The common usage of the adjective "free" denotes that what is freely mine is not imputable to another entity and can - or even should - be attributed to the associated noun. This is something that is clear even to schizophrenics, when they foist the responsibility for things they have done on inner but strange voices that supposedly ordered them.

There is therefore a negative and a positive dimension to the concept of freedom. The negative is usually interpreted as "absence of extraneous coercion", both external and internal, and in this sense it is said that I am free of this or that, or that an animal is free when it is not locked up in a cage, nor does it have electrodes inserted in its brain to mediate its behaviour. We could call this freedom "freedom to" (freedom to go to the cinema, to follow bestial instincts, to sacrifice oneself for a high ideal...). However, in order to fully realise the notion, we need to add explicitly or implicitly to the merely negative freedom ("from what") a positive freedom or "from which agent", i.e. from which subject or at least from which determining factor the most profound decision comes from. In other words: it is a matter of identifying the written request from which the last word has been spoken.

Fuster's book pursues the endeavour to find a credible alternative within the horizon of neuroscience to consciousness, the self, the soul or any other notion foreign to the aforementioned discipline. Consciousness certainly is not, but -according to Fuster's criteria- it would be if it were to become independent and become something more than an epiphenomenon. In his opinion, there is only one solution: the genuine possessor of freedom would be the brain, or at least the part of it most directly involved in processing information and generating responses, that is, the prefrontal cortex.

11 ...human agency is a phenomenon of the brain's ability to choose, rationally or not, between various possible actions.

41 ...many experimental programs of study confirm that the prefrontal cortex exerts putative cognitive-executive control over a wide variety of cortical and subcortical Structures brains, in order to sharpen attention, maintain report of work, make decisions and organise actions with goal.

49n What is free is our bark.

75 The agency is as free as the cortex is to select future actions and prepare for them.

This is all very well, or at least very clear, but it is difficult to avoid that, by preaching freedom as an attribute, the brain in general and the prefrontal cortex in particular are contaminated by the governing and quasi-substantial functions that were once recognised to the soul, subjectivity or consciousness. In other words: the natural tendency of a free, liberated and/or liberating cerebral cortex is to "homunculate", as Fuster shrewdly detects:

42 If we give the prefrontal cortex the role of supreme executive, then the question is what other "controller" or "authority" - cognitive entity or brain structure - does the prefrontal cortex obey; and we could ask the same question about that authority, and so on ad infinitum.

However, it is one thing to detect a danger and quite another to avert it. To prevent an entity with clear functional and anatomical significance -such as the cortex- from becoming something like an immobile engine, a first cause or "a hook hanging from the sky", from agreement with the expression Daniel Dennett likes to use, I don't see Fuster doing much more than forbidding it:

13-4 I want to draw a clear distinction between the simplistic idea of the prefrontal cortex as a mythical "central executive in the brain", which it is not, and its fundamental role in the conception and organisation of actions with goal.

The book is coherent with this purpose, since it does not appeal to elements other than those provided by the experimental technique: nerve pathways that constitute its inputs and outputs, mechanisms of neuronal discharges, release and uptake of neurotransmitters, importance of myelination, etc., etc., etc. It is a structure densely interconnected with itself and its environment, with no gulf separating it from the rest of the brain, the nervous and hormonal system, the soma and final the world. If no alternative factors to natural causality are at work in it, what ontological or functional prerogative allows the phenomenon of freedom to be generated and maintained? I am afraid there are no alternatives left but to appeal to a holism with thaumaturgic virtues or to give chance equally myrific capacities, as Jacques Monod somehow did in his time. With all due respect to these options, which in any case would require a detailed development , I am of the opinion that freedom deserves and demands much more.