Lesson 2021: How does God act in casual events?

summary

God's creative plan seems hardly reconcilable with the contingent evolution of nature, especially with the existence of fortuitous events that condition the direction of natural history. The problem is widely discussed in debates on the relationship between science and religion. I first present a notion of chance inspired by a stratified view of nature. I then present the views of Thomas Aquinas and some contemporary authors. I conclude by arguing for the divine intentionality of creating a potential universe in which God's providence can act in respect of natural laws and in a way that is not rationally controllable.

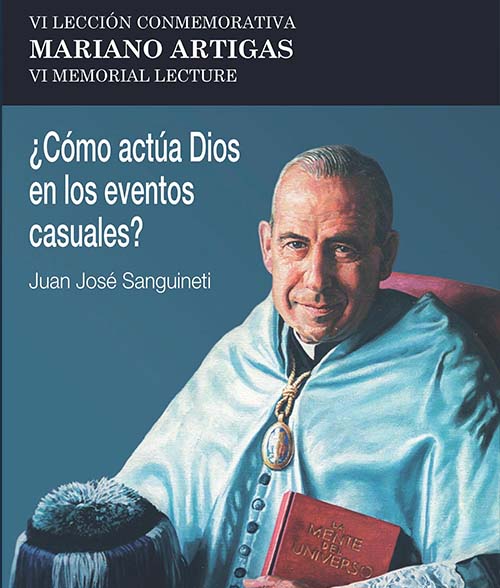

The topic that I am going to present in this commemorative act in honour of Mariano Artigas, with whom I have worked and talked countless times, is the role of chance in the dynamism of the universe and how it can be understood in relation to evolutionary processes and in the light of divine causality. It is a question that preoccupied Don Mariano - may I call him by this familiar name - and about which he has written and spoken on many occasions. He was aware that the image we have today of evolution is characterised by contingency, which was well known and accepted by Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, although not in an evolutionary perspective. Hence the impression we all have today that the biological universe, and also the cosmological platform that makes its origin possible, not being something absolutely necessary, admits a plurality of directions, as well as catastrophes and destructions, to the point that nothing guarantees its future subsistence. This poses a particular difficulty in reconciling it with God's creative action, an action which, being intentional and ordered, seems to imply a plan and a destiny in the grandiose unfolding of the universe, of life and of the appearance of the human species in the ecological environment in which we live.

Mariano Artigas writes in this sense in The Mind of the Universe: "evolution can be combined with a divine plan, although the process of evolution includes progress and failures, because there is no reason to characterise the divine plan as necessarily linear and always progressive. And, on the other hand, we can add that the existence of random events in the evolutionary chain is compatible with the existence of directionality in evolution."1.

The evolutionary view of the cosmos and life seemed at first to be opposed to divine creation. In recent years, and for a long time now, there seem to be no particular theoretical difficulties in understanding how the divine creation of the universe is not only compatible, but also harmonises very well with a universe in which new physical and biological Structures are generated over time. What tends to pose more difficulties, however, now that we are moving further and further away from a deterministic physical conception, is evolutionary contingency, taken in a strong sense.

This feature mainly affects the evolution of life. The development of the universe from the Big Bang to the training of galaxies, stellar and planetary systems, does not pose special philosophical problems in this respect. The coincidences pointed out by the anthropic principle would seem to indicate that our universe is as it were designed to be able to support life, at least on our planet and perhaps on others, though not many in relation to the whole. The evolution of life, on the other hand, seems to be conditioned by so many variables that it does not seem to show a clear deterministic direction, although overall progress is also evident, until we reach the rational animal. It seems, then, to be a contingent evolution, that is to say, susceptible to progress along different paths, in which nothing is absolutely assured, although at the same time there are orienting factors (natural selection, emergencies, potentialities, constraining circumstances).

How, then, can we understand the purpose of a Creator God in such a universe? If God is an omnipotent, wise and benevolent Creator, we have to suppose that he creates a cosmos and assists it not by whim or necessity, without options, but by giving it characteristics that respond to a rational and even loving intentionality. What sense does it make, then, that the evolution of life manifests a high Degree of contingency, a multitude of apparently fortuitous encounters, varied directions, the presence of destruction and many physical evils, and that all this affects man, whose existence on earth is beautiful, but hazardous, full of risks and evils and so fragile that his permanence in the future is not guaranteed? Human history itself seems to be subject to all sorts of contingencies subject . It does not respond to rational planning, but is sample subject to a mixture of human needs, chances and actions, which, as they overlap, create new and totally unpredictable directions, both for good and for evil.

So we are neither in the context of pure determinism, especially if we stick to the natural history of the earth, nor in a completely disordered world in which chance would simply dominate. It is enough today to consider the pandemic we have had to endure to understand almost graphically such a world, the intelligibility and meaning of which we seek with the help of science, philosophy and theology.

Everything is somehow concentrated in chance. Since my intervention will be centred on this topic, I will leave aside the problem of freedom, even though chance also has a lot to do with the free actions of humans.

What makes the development of life in ecological contexts contingent, either positively or negatively, i.e. towards the emergence of enriching novelties or, on the other hand, towards suffering and extinction, are coincidences, which are obviously never pure, but always involve phenomena that are subject to laws that are only to a certain extent rigorously necessary.

My approach here is theological, in a philosophical perspective, although without ignoring what we know from religious faith. As human beings, we want to explain the intelligibility of things in their being and becoming. If we discard God as the principle President of everything that happens in the world, we are heading for nihilism. The question of God and nature arises only on the philosophical level of thought, because it has no place in strict scientific research. This question becomes very acute when we are confronted not just with nature, but with pain, death and chance, i.e. with everything that is disordered and even evil. Chance, in particular, seems to stand apart from causes. What happens randomly does not seem to have any proper cause. How, then, can we relate it to a Creator God who can control everything, foresee everything, and who wills good for human beings? Can we imagine that God somehow intervenes in chance phenomena? Does he do so in such a way that in the end the randomness would be only apparent, for it would conceal a secret divine action that would contain some purpose, as when the Apostles cast lots to see who would succeed Judas, trusting that God would thus reveal his choice?2

These questions have always been asked by pious people in relation to human life, and they are still important. But now they are also addressed to the history of nature, because of all that I have said. With regard to human life, the theological answer appeals to the Providence of God and is in the Gospel ("not one of them [little birds] shall fall to the ground without your Father's permission...even the very hairs of your head are all numbered"...).3). Therefore, what is at issue here is not God the Creator, but his Providence. Can it also be applied to the history of nature, which in former times was not considered necessary, perhaps because it was not known that nature could have a history?

This is the topic of my work4. In contemporary philosophical theology, carried forward by authors concerned with the relations between science and religion - theologians, philosophers, scientists - the problem was seen under the label of "divine action in the world". I am thinking above all of the meetings on this subject sponsored by the Vatican Observatory at Castel Gandolfo and by the Centre for Theology and the Natural Sciences at Berkeley, under the initial impulse of Saint John Paul II, in which researchers such as Robert Russell, Nancey Murphy, William Stoeger, George Ellis, Philip Clayton, Arthur Peacocke, Thomas Tracy, John Polkinghorne, Michael Heller, Francisco Ayala, Ian Barbour and many others took part throughout the 1990s. One fruit of these encounters was a series of precious volumes devoted to the problem of God's action in relation to quantum cosmology, chaos and complexity physics, evolution and molecular biology, neuroscience and quantum physics.5.

This field of study is immense and has been the subject of countless programs of study, with a plethora of views attempting to explain how God could act in a world characterised by contingency and chance. I discard here the well-known extreme philosophical thesis , namely atheism, which assumes or rejects chance in multiple ways, as well as iron determinism, which excludes the existence of chance, and deism, which sees God's action as limited only to the initial moment of creation. In other words, I take the view of a universe created by a God who is also provident and who intervenes in human life with favours and miracles, often in answer to the prayers of the faithful, and sometimes on his own initiative, and I side with those who recognise the existence in the physical world of indeterminacy, contingencies and chance events. Furthermore, I believe that topic should be studied in the light of our current scientific view of nature, and therefore I exclude as unacceptable the position of those who think that in philosophical-natural or theological questions the sciences have nothing relevant to say.

The authors I have just mentioned, including of course Mariano Artigas, generally agree on these points, but differ in the way they explain them.6. These divergences are important and sometimes quite subtle. I cannot pretend to cover them all here. They depend to a large extent on one's conception of the philosophy of nature, sometimes today confused with the philosophy of physics and biology, and also on the theological vision of the authors and, since the action of God in the world is at stake, it is also related to the metaphysical conception of causality, since the problem raised is to associate God's action in the world with physical (or human) causalities. I note, however, that in general in the discussions of this problem, while theological disquisitions abound, the presence of the philosophy of nature is missing, perhaps simply replaced by scientific knowledge.

First, I will examine the nature of chance and its relevance in nature. I will then consider the topic of God's action in the world, especially his providential action and its possible relation to chance. I will consider this problem first in Thomas Aquinas and then in some authors who are at the centre of contemporary debates on the subject, in order to draw some conclusions.

1 . M. Artigas, La mente del universo, Eunsa, Pamplona 1999, p. 216. On this topic see more extensively pp. 211-216.

2 . Cf. Acts of the Apostles, 1, 26.

3 . Matthew, 10, 29-30.

4 . I have touched on this question partially in my two studies, Creazione ed evoluzione. Che cosa direbbe oggi Tommaso d'Aquino nei confronti dell'evoluzione? in S.-T. Bonino and G. Mazzotta (eds.), Dio creatore e la creazione come casa comune, Urbaniana University Press, Rome 2018, 155-168, and Can the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas be compared with modern science, "Studium. Filosofía y teología", Tucumán (Argentina), vol. 23, n. 45 (2020), 103-126.

5 . A summary and balance of these volumes can be found in R. J. Russell, N. Murphy, W. R. Stoeger (eds.), Scientific Perspectives on Divine Action. Twenty Years of Challenge and Progress, Vatican Observatory Publications, Vatican City State, and The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, Berkeley (California) 2008. The initial study in this series of publications was R. J. Russell, W. R. Stoeger, G. Coyne (eds.), Physics, Philosophy and Theology: A Common Quest for Understanding, Vatican Observatory, Vatican City State 1988. A new series of this subject of programs of study has begun, devoted to research on physical evil in an interdisciplinary perspective: see N. Murphy, R. J. Russell, W. R. Stoeger (eds.), Physics and Cosmology, Scientific Perspectives on the Problem of Natural Evil, Vatican Observatory Publications, Vatican City State, and The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, Berkeley (California) 2007. More recently, the Center for the Study of Theology and the Natural Sciences at Berkeley has sponsored a project of research on indeterminism and randomness in nature, associated with problems of theodicy, with the project Saturn: cfr. R. J. Russell, J. M. Moritz (eds.), God's Providence and Randomness in Nature: Scientific and Theological Perspectives, Templeton Press, West Conshohocken (PA) 2018.

6 . Cf., for example, the breadth of explanations presented in a work that can almost be considered a classic today: I. Barbour, Issues in Science and Religion, Harper Torchbooks, Harper&Row, N. York 1996. Barbour, Issues in Science and Religion, Harper Torchbooks, Harper&Row, N. York 1996. For a current overview, cf. I. Silva, Providencia y acción divina, in Diccionario Interdisciplinar Austral, C. E. Vanney, I. Silva and J. F. Franck (eds), URL=http://dia.austral.edu.ar/Providencia_y_acción_divina, 2017.

What is chance? The so-called chance or fortuitous phenomenon, classically also assigned to so-called luck or fortune, first appears in human life as an event that happens accidentally, without anything essentially causing it, nor anyone having proposed it, i.e. apparently outside the order of regular, known, foreseeable causes. It does not just arise out of nothing, but within a complex of flexible circumstances, in which a certain causal defect occurs in a context that is, however, subject to laws. The context is physical contingency, which implies margins of indeterminacy, because contingent is what it is now, but may or may not cease to be, or what it may or may not be in the future.

The context makes the random event more or less likely, not necessary. We rationalise chance to some extent with the mathematical calculation of probabilities and with the empirical verification of frequencies and irregularities through statistics. Probability is not necessary, and to the extent that it is very improbable, if it occurs, we will see it as particularly coincidental, like finding a thousand-dollar note in the street. This meeting chance is beneficial ("good luck"), while other coincidences are, on the contrary, harmful ("bad luck"), although they can also be neutral.7.

A chance phenomenon is a disordered phenomenon, i.e. it lacks at least some causal link. If someone wanders into the midst of a crowd of people "just because", he will meet some individuals simply by chance, as opposed to if he did so because he was pushed by someone else on purpose, or if he did so with some specific intention. There is thus a causal defect here, which can arise from several domains. It can be a lack of finality, or a defect of efficiency, formality or materiality (the four Aristotelian causes). Having in mind the physical philosophy of Leonardo Polo8s philosophy of physics, we could say that in the concausal framework with which we understand physical nature there is a certain defect here, or, in other words, some disorder is present.

Disorder does not mean evil. As I said, sometimes the lack of order can be beneficial, as in the example of the person who finds money by chance, without having proposed it and without having put the appropriate means in place to find it. The only "order" that can be glimpsed in these events is that we are dealing with a system that foresees the possibility of fortuitous phenomena occurring, just as in a card game we are dealing with a causal system designed so that good or bad luck can occur.

The chance event is not necessary. It is therefore contingent, and that implies a certain potentiality. It may or may not be, it may or may not actually happen, and not because of our ignorance of the causes. It does not matter that ignorance is involved in the human examples I have just given. It is not the case that the die that falls on one side falls by physical necessity and that we simply ignore it, so that such an event would not actually be fortuitous. This objection would be valid only if we consider nature in a monocausal way, in this case, at its lower physical level, without looking at the concausality of the system as a whole. Obviously the die necessarily falls on one side because of the gravitational force. But fortuitousness arises when a person, objectively, throws the die without being in full control of what he does, and moreover in this case he wants to do so, that is to say, he wants to "free himself to chance".

It is often said that chance arises from meeting between independent causal series, as in the Aristotelian example of the unsought meeting with a friend in the marketplace.9. This is true, but it needs to be explained further. In chance encounters some indeterminacy is present. It is a defective indeterminacy. By contrast, freedom implies a positive indeterminacy, not necessarily a defective one, because, on the contrary, freedom implies an openness to many possibilities, as when we can choose a series of gifts for our friends. However, our finite freedom always involves some Degree of imperfection, because we do not fully master what we do or what we intend to do (in choosing gifts, we can make mistakes).10.

Chance events are known only if we put ourselves in the individual perspective, which is the most real and concrete one. When we generalise we place ourselves in a necessary conditioned, or at least probable, view, whereas the chance event is always a particular case. Sometimes it is seen, from the generalisation, as an "exception to the rule" and therefore as a rare event. This view, however, is partial. If we look at everyday life, we will find it full of innumerable coincidences, which we often fail to take into account. When we go out into the street, we meet a multitude of people by chance every day. Such coincidences can be the beginning of an important historical development in our life. We lead a regular life, but if we have an accident or, on the contrary, a favourable chance meeting , such as when our parents met and got married, it has significant historical repercussions in life. Chance, then, although it is risky and can be dangerous, introduces novelty and richness into human life. Our whole life is made up of a mixture of needs, free actions and chance. And so is the whole of human history.

This outline of chance in the context of a causal world, if we exclude freedom, can be applied analogically to nature. For this I will not turn primarily to the sciences, but to the Aristotelian-Thomistic natural Philosophy , which contains elements that can be taken into account today if we separate it from the ancient physical vision and interpret it not literally but freely inspired by its essential aspects (without a historiographical purpose ).

The central point here is hylemorphism graduate or, if you like, a hierarchical view of strata, according to which a lower level, with its autonomy and its own laws, is informed by an emerging higher one, in which new essential notes appear. The relationship between these two strata is subject material and formal. The lower level is the material base on which the higher one is installed, which acts as a formal causality. The formal level is irreducible to the material level, but can subsist and act only in dependence on the latter, so that the disorganisation or indisposition of the material base leads to the disappearance of the emerging form (in the case of life, to illness and death).11. This occurs at various levels, in stages, but for what concerns us it occurs above all at the physical-chemical level in relation to the biological level, with many intermediate or collateral sub-levels. Moreover, the relationship form-subject cannot be understood univocally at the various levels. Following the indications of Polo's natural Philosophy , the concausal binomial subject-form must always be understood as associated with formal and final causality.

On the other hand, we should not only look at the hierarchy of substances, but rather consider complex substances, with their internal vertical, horizontal and transversal causalities, from subject formal-material-efficient-final, as systems (e.g. organisms) which are in relation to other external units within a certain environment, from which in turn all subject of causal influences originate (and so on up to the whole cosmos). The picture is thus hierarchical-systemic. The relationship of each unit to its environment is fundamental. This is also true of man, with his neurobiological constitution, his spiritual Schools (which are not simply "emergent") and the culture that he creates as an environment, for example, with technology and the products of his work. Coincidences must therefore be studied bit by bit, case by case, only in this highly complex context, and are thus practically impossible to master rationally. They can only be managed with approximations, prudential decisions and risks.

Complexity implies, in this picture, that the higher formal level arranges the material base in a new way, without violating its autonomy. The lower level has its own causal determinations, but it is open to a formalisation that uses these determinations in a new sense, just as life takes advantage of physical-chemical properties to put them at the service of vital functions, or as man organises physical things to create technical objects. The lower level is "indeterminate" in that it is not rigid, but is susceptible of being informed by a higher hierarchical-formal Degree , although in its own order it is determined ad unum, i.e. it only univocally realises a series of its own effects. Physical laws are rigorous, but this does not prevent artistic and technological creations, without violating the lower physical order.

Chance arises, then, when the control of the higher level over the lower one is deficient. Thus it is accidental that an animal suddenly falls off a cliff and dies, because it has not been able to control its movements (its perception, its locomotion) properly. In this accident, it has been left at the mercy of the lower causalities, without being able to order them correctly according to their higher completion. The chance event, as I said, can be favourable or unfavourable. It will be favourable, for example, if the animal finds by pure chance a place populated by objects appetizing to its instincts.

When a higher formality operationally dominates over lower perfections or Materials, the risks posed by chance are smaller and more controllable, while they increase when the higher formality weakens its action. This explains why, with ageing and the progressive weakening of a person's strength due to illness, the probability of any random factor damaging the organism increases. Therefore, an inebriated person, to use another example, because he or she is not controlled "from above", is more exposed to any accident. Even if the accident is necessary from the point of view of the lower forces, it is random if the higher (weakened) perfection is considered. The disorder that is introduced "by chance" makes the transition from the necessity of form to the necessity of subject, i.e. it consists of a "descent" to the lower order. The drunken person, if we continue with the example, will no longer act according to his due rational order, but rather in the manner of an inert body, according to the necessary laws of physical bodies, which is not a disorder for a lump of stone, but is a disorder for a human or a living being.

It is often said that material indeterminacy depends on a certain instability of the subject, which is characteristic of the Aristotelian hylemorphic view.12. This is true if it is understood concausally. Physical things easily lose their forms, without detriment to the rigour of physical laws, which are always valid in the abstract and in a conditioned way. This is why we live in a world in flux, in which nothing is absolutely certain and nothing subsists forever. Such a world is random and contingent. Formalisations, by transcending the levels Materials, imply a certain victory over chance, which can be exploited and "tamed", as people do when they play at chance and probabilities, with many risks. Chance, in this sense, is both positive and negative. It is only through the flexibility and openness of the lower causalities that the higher formal levels can emerge, when circumstances are favourable at certain times. But chance is also at the root of corruptions, diseases and sufferings, phenomena that have traditionally been seen as accidental, because of the weakness of the physical Structures .

7 . M. Artigas considers chance in Filosofía de la naturaleza, Eunsa, Pamplona 1998 (4th renewed ed.), pp. 242-244.

8 . Cf. my study knowledge y mundo físico en Leonardo Polo, Sindéresis, Madrid 2020.

9 . Aristotle studies chance and fortune with his usual acuity in the Physics, book II, 195 b 31 to 198 a 14. For Aristotle, chance and fortune correspond respectively to nature and man. See the comments of St. Thomas to Aristotle on this topic, and more extensively the valuable work of R. Alvira, Casus et fortuna en Santo Tomás de Aquino, "yearbook filosófico", 1977 (10), 27-69. See also N. Kahm, Divine Providence in Aquinas's Commentaries on Aristotle's Physics and Metaphysics, and its relevance to the question of evolution and creation, "American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly", 2023 (87), 637-656; L. Congiunti, Ordine naturale e caso secondo Tommaso d'Aquino, "Espiritu", 2017 (66), 303-323; A. M. Minecan, Chance as a positive space of indeterminacy in the Thomistic assimilation of Aristotle's physics, "Areté" (30) 2018, 271-287. I study the notion of chance as disorder in my work La filosofia del cosmo in Tommaso d'Aquino, Ares, Milano 1986, 236-240 and the notion of chance and contingency in Azar y contingencia, published in Scritti filosofici, Edusc, Roma 2020, 1261-1272.

10 . Normally by "indeterminacy" we always connote some causal defect. Thus, God creates freely, without necessity, but we do not say that divine action is indeterminate. Freedom is self-determination.

11 . Without knowing hylemorphism, he argues for a hierarchical emergentist conception of this subject, as a basis for explaining God's action in nature "from above", G. Ellis, Ordinary and Extraordinary Divine Action, in J. R. Russell, N. Murphy, A. R. Peacocke (eds.), Chaos and Complexity, Vatican Observatory Publications, Vatican City State and The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, Berkeley (California) 2007, 359-395. Similarly, he puts forward a holistic emergentist view according to Degrees I. Barbour, Indeterminacy, Holism and God's Action, in T. Peters and N. Hallanger, God's Action in Nature's World, Ashgate, Aldershot (England) 2006, 113-128. However, these authors are interested in seeing how God could act with a top-down causality in an emergentist universe, in which things are not reduced to their lower strata Materials . My point, on the other hand, is that this view, somehow close to a "hylemorphism according to Degrees", proper to Aristotle and St. Thomas, allows us to understand chance as a natural phenomenon. Only then can one study how God acts in this scenario of chance.

12 . I consider this point in knowledge and the physical world in Leonardo Polo, 2020, cit. pp. 122-127.

I now turn to the relationship between chance events and the Will of God. If we say that a chance event was actually willed by God, it would seem that we are neutralising chance. On the other hand, in the traditional metaphysics of creation, God does not limit himself to creating at the temporal beginning of the cosmos, because the creative influence is permanent and supra-temporal and affects not only the existence of things, but his own concrete action at all times. However, this does not imply occasionalism, i.e. it does not imply the elimination of the causalities proper to things. God does not create a passive world, but a universe with real "second" causes. Creative causation gives created things their own causal powers. But transcendental causality, having to do with the actus essendi, cannot be remote. It is, on the other hand, the human government of things, where the primary decision-makers do not enter directly into the management of particular tasks.13.

Everything that happens in the world, in its smallest details, responds absolutely to the creative power and intentions of God. This Thomistic thesis does not, however, justify determinism or fatalism, which would remove responsibility from our actions. For Aquinas, the divine creative and provident action does not detract from the consistency and autonomy of second causes, be they necessary, contingent or free, since God wills precisely such a world and not a monotonically deterministic one.

On the basis of these points, Thomas Aquinas affirms that God's providence does not exclude the contingency of things, nor does it exclude the freedom of God.14nor freedom15nor random events16and, as if to avoid the possible interpretation ("deistic", we could say), that God would act in these areas in a generic way, "caring" only for the species but not for the individuals, or providing for these things only in a mediate way, unloading "his responsibility" on the second causes, Aquinas maintains that God's providence reaches all contingent and individual things, even the smallest ones, and that it does so in an immediate way, but in an immediate way.17and that it does so immediately, but distinguishing in this case between ordination(ordinatio) and execution(executio), so that only with respect to the latter can it be said that God governs everything by means of second causes.18.

This position is quite strong and does not remove the mystery of understanding divine action in the world as absolutely radical and not as simply "concurrent", as if it were a con-cause placed on the same level as the others. However, it is courageous to maintain that "it would be contrary to the reason of providence and to the perfection of things if some coincidences did not exist".19adhering to the Qoheleth phrase that "time and chance come to all things".20. David Bartholomew argues that chance serves God's purposes and contributes to the richness of this world (this is not a Leibnizian position) and praises Thomas Aquinas for his acceptance of the reality of chance in a world governed by God.21.

Aquinas explains the relationship between the casual event and God also according to the outline of particular causes and their own "intentionalities" and a higher cause that can coordinate them according to a higher intentionality, which transcends what is given by the causes that are subject to it. His most concrete explanation, in this sense, appears in S. Th., I, q. 116, where he writes that

It may happen that something, with respect to lower causes, is fortuitous and accidental, but that it is intended with respect to a higher cause. As if two servants of a master were sent to the same place without their knowing it. The meeting between the two is fortuitous, if we refer it to themselves, because it is outside their intentions. But referred to their master, who thus preordained it, it is not accidental, but intended.22.

This example has the advantage of pointing out how God, with his Intelligence situated in eternity, can foresee that in time a co-ordination takes place which at the level of second causes would be only per accidens, casual. God's pre-ordination does not eliminate the proper consistency of causes which in themselves would not co-ordinate, as St. Thomas points out when he says that "nature in itself cannot cause someone who goes to dig a grave to find a treasure", but an intellect can understand the phrase per accidens that "one who dug a grave found a treasure", and "if it can with its intellect, with the intellect of the intellect, understand that one who dug a grave found a treasure", and "if it can with its intellect, with the intellect of the intellect of the intellect of the intellect".23and "if he can with his intellect apprehend this, he can also do it".24. Somehow there is here a resonance of the fifth way that leads from the perception of an order to the postulation of an intelligence. However, the example has its inadequacies, because then it would seem that chance is unreal, since someone secretly prepared it.25. The examples serve for what they are intended to illustrate and nothing more.

The approach of St Thomas that I have just discussed refers to coincidences in human life and not so directly to natural phenomena. Nevertheless, Aquinas, together with Aristotle, recognises the existence of more or less probable contingent effects of subject biological or climatic (health issues, rainfall, good weather), and also in this physical sphere he admits coincidences, insofar as the normal causes of events can be prevented by a causal deficiency. This fact, however, being in paucioribus26, has no further significance in a stable, cyclical universe. It affects individuals, but not species. Quite different is the scenario of the evolutionary universe we know today thanks to science, where chance phenomena can produce important changes in the direction of natural history.

13 . On these points of the metaphysics of creation, cf. Thomas Aquinas, S. Th., I, q. 105, a. 5 (God works intimately in any operation or action of created things) and, more broadly, qq. 103-105 (on divine Providence, called by Aquinas "government" of God over the world). St Thomas takes as model of God's Providence the human government of things, and to explain how an action can be both of God as first cause and of the creature as second cause he resorts to model instrumental causation (cf. GC, III, c. 70). Since these models are always imperfect, Aquinas obviously purifies their meaning so that they can be applied to God without prejudice to divine perfection (for example, the human ruler does not attain everything; the instrumental cause properly speaking does not have autonomy).

14 . His indefectible Will does not impose necessity on all second causes: see S. Th., I, q. 19, a. 8.

15 . Cf. GC, III, c. 73.

16 . Cf. ibid. c. 74, as well as S. Th., I, q. 116.

17 . Cf. GC, c. 75.

18 . Cf. ibid., cc. 76 and 77; S. Th., I, q. 103, a. 6. Cf. also S. Th, I, qq. 22, 103 and 116 in full, on divine providence. Cf. on this topic E. Durand, Évangile et Providence, Cerf, Paris 2014, pp. 131-183.

19 . GC, III, c. 74.

20 . Qohelet, 9, 11. I translate from the Latin version used by Aquinas.

21 . Cf. D. Bartholomew, Dio e il caso, Sei, Turin 1987, p. 201 (original, God of Chance, SCM Press, London 1984). Cf. also by the same author God, Chance and Purpose, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008. Bartholomew's position, though not entirely clear, seems to assume that God opts for a world containing chance because it is much richer in possibilities, accepting the risks that this entails, but without having to be attributed a precise intentionality with respect to every chance event. God would let things happen and act with his special Providence when he deems it necessary. He gives as an example the father who lets his young son play on his own so that he can learn(Dio e il caso, p. 268). This subject of models, like those given by St. Thomas and other authors, despite their imperfections, are illustrative, as are the parables of the Gospel (God as king, master of the house, allocator of talents, contractor, etc.). In St. Thomas' position the fortuitous event does not escape God's causality and intentionality, at least permissive. But it is not the case that God shrinks from acting so as to "allow" chance events. Moreover, if those chance events are harmful, God knows how to reorder them for the good.

22 . Thomas Aquinas, S. Th., I, q. 116, a. 1.

23 . S. Th., I, q. 116, a. 1.

24 . Ibid.

25 . On the topic that I have just presented in St. Thomas, cf. I. Silva, Revisiting Aquinas on Providence and rising to the challenge of Divine Action in nature, in "The Journal of Religion", 94 (2014), 277-291, and Providence, contingency, and the perfection of the universe, "Philosophy, Theology and the Sciences", 2 (2015), 137-157. Cf. also J. M. Maldamé, Création et Providence, Cerf, Paris 2006, pp. 146-148; Création par evolution, Cerf, Paris 2011, 215-232; M. Dodds, Unlocking Divine Action, Catholic University of America Press, Washington 2012, 109-113.

26 . For Aristotle and St Thomas, contingent events can happen frequently or rarely, and the latter are casual: cf. Aristotle, Physics, book II, 196 b 10-15; Thomas Aquinas, In II Phys., lect. 8.

Contemporary science has progressively moved away from the initial rejection of chance typical of modern rationalist science. An indeterministic (non-absolute) image has been imposed, albeit subject to discussion, both in microphysical processes at the quantum level and in the field of the physics of complex systems (chaos physics) and in evolution, due among other things to random mutations. I will not discuss here the topic of physical determinism and indeterminism and their relation to the interpretation of natural laws.27i.e. whether it is epistemic or truly ontological. If there is real indeterminism, there is randomness in nature.

For many theologians this might have made it difficult to accept finalism in nature and thus the belief in a God who creates the universe with a purpose. But paradoxically, indeterminism opened the door to thinking about special divine interventions in the world, which had previously seemed forbidden because of the rigid determinism with which classical physics was interpreted (in a hard deterministic conception miracles seemed unthinkable violations of physical laws).28. Determinism could in any case lead to the acceptance of a deistic version of creation (God as the first cause of a chain of absolutely necessary events). Thus Darwinism, which seemed to disqualify a divine teleological plan in the world of life, would not pose any difficulties for a theological view of nature, if one had recourse to God's provident interventions in the world. Thus, the attention of theologians shifted from the topic of creation to that of providence.29.

The scholars I consider in this paper generally try to find spaces of indeterminacy that would make possible a divine intervention in natural processes that would not be interventionist, i.e. that would not simply violate natural laws. Nor are they always opposed to this, but they see it as less congruent with God's wisdom, and they do not want to multiply miracles everywhere to explain how God can interfere in evolutionary processes.30.

On the other hand, the distinction between general and special Providence is at stake. General Providence would be an "ordinary" divine action beneficial to man (e.g., preserving his health, caring for him in his travels, assisting in a good harvest, etc.), or preserving the course of evolution in the direction willed by God.31While special Providence would refer to special, one-off actions, miraculous or otherwise, in which the Creator would act in some natural events, so that without that intervention the natural effect willed by God would not have occurred, so that natural causes would have followed their normal course.

Special Providence, therefore, is in some ways "interventionist", although there are different ways of understanding it. The strongest consists of miracles, for example, the water turned into wine at the wedding at Cana. The weaker, not empirically verifiable, is constituted by divine favours, as when we pray for someone to be cured of an illness or to find a job, and this happens, but not in a miraculous way. Today we also pray for the pandemic to be attenuated, as it has always been done in epidemics, by appealing to God's mercy.

The theologians involved in these debates generally value positively the existence of indeterminacy in nature. They do not see it simply as a causal defect, but as a feature that brings about more richness and variability in the potentialities of nature. Nor do they think that to postulate a divine action that "completes" indeterminacy, that is, "determines" it in some sense, is to turn to the God of the gaps. Rather, they believe that provident action in nature would be from within, not from without, and that it would be quite natural for God to have made a world in anticipation of being able to intervene in it in ordinary or extraordinary ways, just as he created man to complete the work of creation with his labour. As theologians, they relate these interventions to God's salvific plans with regard to human events, pain, suffering and the eschatological future.

Naturally, what these authors write about this topic is propositional. They admit Providence, whose actions are not empirically discernible, and they do not pretend to answer scientific problems. They try to give a version of an eventual action of God in the world that is consistent with what we know from science and religious faith. They also seek to explain the reasons God may or may not act as we might expect, always in the context of the plans of redemption and salvation.

27 . Cf. on topic C. Vanney, J. F. Franck (eds.), ¿Determinismo o indeterminismo?, Logos, Universidad Austral, Rosario (Argentina) 2016.

28 . R. Kojonen argues convincingly that even classical physics does not conflict with the possibility of miracles, unless it is interpreted in a Closed and complete way, which does not belong to science, but to a philosophical interpretation of science: Is classical science in conflict with belief in miracles? Some bridge-building between philosophical and theological positions, in R. J. Russell, J. M. Moritz (eds.), God's Providence and Randomness in Nature: Scientific and Theological Perspectives, 2018, cit., 205-234.

29 . I do not include in these reflections the position of Intelligent Design, which does not usually appear in the discussions I contemplate in this work. This theory is flawed in that it denies evolution and considers that the intervention of an intellect in major evolutionary changes should be part of science itself. From my point of view, the arguments about the design or plan of an intelligence resort to a very traditional argument that sees in the order of the universe the need to affirm an ordering Intellect (the fifth Thomistic way to prove the existence of God), but they sustain it in a very deficient way and do not take into account the distinction between science and Philosophy. Cf. S. Collado, Panorámica del design inteligente, in "certificate Philosophica", 17 (2008), 17-42.

30 . See on this topic, in general, K. Ward, God, Chance and Necessity, Oneworld, Oxford 1996; D. Edwards, How God acts, Fortress Press, Minneapolis 2010, 57-75; E. Durand, Évangile et Providence, 2014, cit., 31-70; I. Silva, Providence and Divine Action, 2017, cit.; I. Silva, S. Kopf, Divine and Human Providence: Philosophical, Psychological and Theological Approaches, Routledge, N. York 2020 (especially the foreword by I. Silva).

31 . For example, when the Lord says that God the Father makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good: cf.

In what follows, I will refer to three significant scholars along the lines of what I have just presented, namely Nancey Murphy, Arthur Peacocke and John Polkinghorne. With some nuances, other scholars could be included in similar proposals.

Nancey Murphy considers that ordinary divine action in nature could be viewed from thebottom-up, at the quantum microphysical level.32. The first author to advance this idea in a relevant way was William Pollard33although there was no shortage of precedents, such as Sir Edmund Whittaker and Karl Heim34. This hypothesis stems from the difficulty that quantum mechanics encounters in providing a natural explanation for the production of quantum events, although the wave function describes a perfectly deterministic and, one might say, "potential-laden" state of the physical system. The collapse of the wave function that occurs in the measurement gives rise to a singular event that is unpredictable within a framework of possibilities. Being unpredictable, it is configured as a random event, certainly according to probabilistic canons. For many authors, this would be the ultimate root of the indeterminacy of nature, since this quantum indeterminacy would have repercussions at the macroscopic level, although this point has never been perfectly clarified. For some authors, such as Murphy, it seems legitimate to postulate at this level an intimate divine action that determines what is naturally indeterminate.35. The position of the author (theologian) I now consider is very well summarised in the following words of Robert Russell, who with some nuances follows her on proposal:

Murphy's perspective is useful meeting several reasons. The idea of God acting in all quantum financial aid the theological thesis that God does more than just sustain the existence of all events and processes; in fact, God sustains, governs and cooperates with all that nature does. This idea offers us a subtle but compelling way of interpreting God's action that guide both general and special providence. Schrödinger's cat sample that God's action at the quantum level affects two very different kinds of macroscopic effects. It produces the ordinary world of the cat and the Geiger counter (the ordinary physics of the solid subject and Ohm's law, the routine biology of metabolism, and so on), which we describe as general Providence. But it also gives rise to specific differences in the ordinary world-the cat alive, rather than dead-when God acts in one way rather than another in a specific quantum event. For example, God acts with nature in such a way that the particle is emitted now rather than later, or is emitted in the x direction rather than the x direction, and so on. The way God acts determines (indirectly) a specific result in the ordinary world. Thus, we can attribute a special providence to the cat that is spared death and guaranteed life at the crucial time36.

Murphy's opinion is not exhausted in this thesis on God's providence, but is much broader and richer. It is followed, among others, by Robert Russell, as we see here, and also George Ellis, with other nuances, as well as Ian Barbour.37as well as Ian Barbour. For the latter, special quantum events, with their macroscopic amplifications, could explain indeterminate neuronal dynamics, or certain genetic mutations. This would be the way in which God could guide nature in the evolutionary processes, always acting in this "hidden" way.38. I do not think this is occasionalism, but a vision in which God the Creator foresees that he could "fill in" the lack of act in the physical world he has created, a completion that would give him the possibility to intervene in an extraordinary way without violating natural laws.

There has been no shortage of criticism of this position, the main one, in my view, being that of Nicholas Saunders, who does not find proposal convincing for several reasons, among which he invokes that "one does not see that there is any reason why one could not hold that quantum entities are determined by something other than God in the physical system".39. It all depends, then, on one's interpretation of quantum physics. Claudia Vanney argues that the theological implications of quantum theory are conjectural and depend on how one understands the indeterminacy implied by quantum theory.40.

Personally, I think that in a physical and cosmological vision such as the one proposed by the philosopher Leonardo Polo, one could glimpse broader causal aspects than those that physics takes into account, which would give a reason for physical events and processes, in a philosophical perspective, without eliminating their contingency and the lack of full actuality in them. Because of its becoming, the physical world is not fully intelligible, nor does it have a perfect identity, hence the difficulty of conceptualising it in scientific physics.41.

Arthur Peacocke (d. 2006), on the other hand, holds a more metaphysical view of God's action in nature. On the one hand, for this author the universe contains a mixture of necessities, due to natural laws, and potentialities, characterised by openness to possibilities through random phenomena.

One gets the impression that the universe has potentialities that are actualised by the joint operation, in time, of chance and law, of time-dependent random processes in a framework of properties determined by the laws, and that these potentialities include the possibility of biological and therefore human life.42.

In the whole of the flexible and potential processes dominated by the laws, according to Peacocke, an intimate action of God is present, holistically and top-down, in the manner of an all-embracing and active totality that is at the same time personal. The Creator is immanent to the cosmos and at the same time transcends it, in a manner similar to the operative presence of the Logos according to the Stoic or Neoplatonic worldviews and assumed in a higher sense by the prologue of the Gospel of John and by many Fathers of the Church. This divine presence is dynamic, i.e. it implies a continuous and ever-renewed action in the physical processes, like a personal background that gradually influences the evolving parts, or, better, like a musical composer who works out the melody or even inspires a dance.43. Such a God in a certain sense self-limits his power, in order to respect the processes and to make it possible for novelties to emerge creatively from them, and even suffers with the world, especially with the human being, without fully knowing the contingent futures, because before what is not yet there would be nothing to know, without detriment to the divine eternity and omnipotence.

Ian Barbour (d. 2013) finds this less "macho" and externalist view of creation attractive, in which God "plays" with the world not as a supremely domineering Being, but as one who abases Himself, patiently, lovingly, with the times, often testing and sharing in human suffering. God would not be here anoverpowering God, but a God whoempowers things and brings them to maturity, often through suffering.44. The author points out the closeness of these points to process theology, which he views sympathetically.

The positions of Peacocke and Barbour, like those of the process theologians, in their eagerness to unify God with the events of the world end up being too general and even confusing. It is true that "in Him we live, move, and exist", but we have to discern between "in Him we live and move and exist" and "in Him we live and move and exist".45but we have to discern between what is God, what is nature and what is man. Peacocke's thesis is fascinating at times, but it anthropomorphises the Creator too much. All that is said about the kenotic dimension of a Godhead who reckons with created imperfections applies much more concretely and effectively to the incarnate Word, Jesus Christ, who had to live as one with the coincidences of ordinary life and was always protected by the Father.

John Polkinghorne (d. 2021) is more cautious in his considerations of how God acts providentially in the world. The openness of physical causal processes makes more intelligible and natural the particular providential interventions of God in events, who uses second causes for this purpose, although he may also operate by miracles. On the other hand, the regularity of natural processes is also due to God the Creator and is a sign of His fidelity.46.

The open-ended flexibility of the world process provides the means by which the universe explores its own potentiality, humanity exercises free will, and God interacts with his creation. The former, through its limitation and frustration, gives rise to physical evil. The latter, through its sinfulness, gives rise to moral evil. The world thus damaged is not abandoned, for the third is the means by which the Creator can exercise providential care within the evolutionary history of his creation.47.

Providential action, foreseen for a world in need, should not be seen as extrinsic interference, but as part of the Creator's plan, even if it is normally hidden.48. Hence the meaning of prayers, on which God counts as a partnership of the human being that requires union with the Lord and the humility to accept his will.49. Prayer "makes it possible for God to do something that He would not have done if we had not asked Him to do it order".50. If we can act in the world in so many ways, why should it be strange for God to do so?51. Polkinghorne proposes to take as model the action of man in the world, always in his relationship with God, in order to understand in some way the divine action in created and human things, so that it does not seem trivial, strange or difficult to understand.52. "We and God are both capable of acting in the world".53Is this not resorting togaps in physical explanations? No, because these "gaps" are the openness and indeterminacy of the world. Ironically said: "We are people of the gaps, and God can also be a God of those gaps, in a perfectly acceptable way".54.

God's action, according to this author, normally goes unnoticed. That is why one cannot simply say "this event is due to nature" or "this event is due to God", for it can be due to both in various ways, according to the plans of the Creator.

God neither does everything, nor does he do anything, but interacts, with patience and love, in the process of his creation, to which he gave his own due measure of independence. This intermingling of providential grace with the freedom of nature means that divine action is not demonstrable by experiment, though it may be discernible by the intuition of faith....55.

What does this action of God look like? Polkinghorne does not see divine intervention at the quantum level as convincing.56He prefers to conceive of it as taking advantage of the causal openness evident in chaos theories (a point not shared by other authors). He suggests that God could act by introducing information. "It is a coherent possibility that God interacts with the history of his creation through an input of information into the open physical processes".57. In any case, his idea is to take as model the action of the immaterial human mind on the brain, taking advantage of the indeterminate openness of chaotic neural processes, to conjecture that God could act on things in a similar way.58.

However, like Peacocke, Polkinghorne considers that God's providential action in the world, if the future is indeed open, implies that the Creator does not know it before it is realised59. I think that on this point the metaphysics of Thomas Aquinas may help, for whom God does not know the contingent future as being in time, but with the view of eternity, which in no way detracts from the contingent or free character of what happens.60.

On the whole, I find Polkinghorne's view, despite some flaws that may be attributed to it, more persuasive than the others I have presented, not because it resolves the problem definitively, but because he argues from a stronger theological view, in which his confidence in prayers and in the concrete providential action of God is captured. "The motivation for belief in divine providence is rooted in religious experiences of prayer and trust in a guiding God" (p. 4).61.

Indeterminism seems necessary for there to be room for God's providential action to answer prayers. According to Thomas Aquinas, if all the events of the world were absolutely necessary, the prayers of the faithful would be useless.62. As N. Murphy says: "If there is no sense in which a certain state of affairs can be expected to come about which would not otherwise have come about, then the practice of petitionary prayer would be without foundation".63

32 . Cf. N. Murphy, Divine action in the natural order, in Chaos and Complexity, 2007, cit. pp. 325 and 357.

33 . Cf. W. Pollard, Chance and Providence, Scribner, N. York 1958.

34 . Cf. N. Saunders, Divine Action and Modern Science, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2002, 94-126.

35 . Physicists do not normally see the need to resort to a transcendent principle to satisfy the requirement of causality in quantum mechanics. This can be interpreted as result of our ignorance, in a deterministic conception, or as being content with the limits of a purely statistical and holistic physics that says nothing about the supposed singular events. The topic is arduous and vast and obviously impossible to deal with in these pages.

36 . R. J. Russell, Cosmology. From Alpha et Omega, Fortress Press, Minneapolis 2008, p. 187. For Russell's full robust view, apart from this Issue, cf. his article Divine action and quantum mechanics. A fresh assessment, in R. J. Russell, Ph. Clayton, K. Wegter-McNelly, J. Polkinghorne (eds.), Quantum Mechanics, Vatican Observatory Publications, Vatican City State, and The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, Berkeley /California) 2007, 293-328.

37 . Cf. G. Ellis, Ordinary and Extraordinary Divine Action, 2007, cit.

38 . Cf. I. Barbour, Indeterminacy, Holism and God's Action, 2006, cit. Some authors have argued that such brain indeterminacy allows, in turn, the action of freedom on the human brain.

39 . N. Saunders, Divine Action and Modern Science, 2002, cit., p. 117. This criticism refers to works prior to the work we have quoted from Murphy, but it is useful for what we have mentioned about the author.

40 . Cf. C. Vanney, Is quantum indeterminism real? Theological implications, "Zygon. Journal of Religion and Science", 50 (2015), 736-756.

41 . Cfr. Polo, L., Obras completas, Curso de teoría del knowledge, 4 vol., Eunsa, Pamplona 2015-2019.

42 . A. Peacocke, Creation and the World of Science, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1979, 103-104.

43 . Cf. A. Peacocke, Paths from Science towards God, Oneworld, Oxford, 2001; Chance and Law in irreversible Thermodynamics, Theoretical Biology, and Theology, in Chaos and Complexity, 2007, cit. A similar view can be read in E. Johnson, Does God play dice? Divine Providence and Change, "Theological Studies", 57 (1996), 3-18, closer to Thomism in some points. Something similar, but in a strictly Thomistic dimension, can be read in J. Aquino, I. Silva, Una evolución emergente que incluya elementos de azar, ¿can refer to a Creator God? in C. Vanney and J. F. Franck (eds.), Determinism or Indeterminism? 2016, cit., 491-512.

44 . Cf. I. Barbour, Indeterminacy, Holism and God's Action, 2006, cit.

45 . Acts of the Apostles, 17, 28.

46 . Cf. J. Polkinghorne, Quarks, Chaos and Christianity, Crossroad, N. York 1997, p. 72.

47 . J. Polkinghorne, Science and Providence, Shambala Pub., Boston 1989, pp. 67-68.

48 . According to N. Murphy, the Creator acts in a hidden way so that we do not presumptuously rely on God's protective action and so that we act, as God wills, with responsibility and with recourse to second causes: cf. Divine action in the natural order, in Chaos and Complexity, 1995, cit.

49 . Cf. J. Polkinghorne, Science and Providence, 1989, cit. pp. 36-76.

50 . Ibid., p. 71. The phrase is a quotation from P. Baelz, Prayer and Providence, SCM Press, London 1968, p. 118. "When we pray, the first thing we do is to offer God a space for God to manoeuvre and use in the most effective way with respect to his manoeuvring space, from agreement with his providential will. Put more traditionally, we offer our will to be aligned with the divine will. I believe that when this alignment takes place, things are possible that are not possible when human and divine wills have opposite purposes. Thus, prayer is genuinely instrumental, Genuinely world-changing": J. Polkinghorne, Quarks, Chaos and Christianity, 1997, cit. p. 75.

51 . Cf. J. Polkinghorne, Quarks, Chaos and Christianity, Crossroad, 1997, p. 64.

52 . Cf. ibid., pp. 62-78.

53 . Ibid., p. 65.

54 . Ibid., pp. 71-72.

55 . Ibid., p. 72.

56 . Cf. J. Polkinghorne, The Metaphysics of Divine Action, in Chaos and Complexity, 1995, cit. pp. 152-153.

57 . J. Polkinghorne, Quarks, Chaos and Christianity, 1997, cit. p. 71.

58 . Cf. J. Polkinghorne, The Metaphysics of Divine Action, 1995, cit. p. 155.

59 . Cf. J. Polkinghorne, Quarks, Chaos and Christianity, 1995, cit. pp. 73-74.

60 . Cf. Thomas Aquinas, S. Th., I, q. 14, a. 13. See, on this topic, S. Brock, Sulla causalità della preghiera di petizione: C. S. Lewis, Peter Geach e Tommaso d'Aquino, "certificate Philosophica", 23 (2014), 79-88.

61 . J. Polkinghorne, The Metaphysics of Divine Action, cit. p. 155.

62 . Cf. Thomas Aquinas, S. Th., II-II, q. 83, a. 2.

63 . N. Murphy, Divine action in the natural order, 2007, cit. p. 331.

The responses of group of theologians concerned with divine action in the world are in continuity, albeit partially, with the Thomistic thesis that God intervenes in natural and human chance in his providential government both general and special, and that chance and contingency give nature, not to say human history, a greater potentiality and versatility capable of engendering richness and variety in an indefinite and ever-open-ended way. The Admissions Office of chance in physical realities is an acquisition of contemporary natural sciences. The concrete modes of divine intervention proposed by these authors, for example at the quantum level or in the causal flexibility contemplated by the sciences of complexity, may be debatable from a technical point of view. But they all agree that divine providence can be exercised only if natural processes have margins of potentiality and indeterminacy.

Chance, in this perspective, is not an isolated or exceptional phenomenon, annoying for causality theorists, but must be understood in the context of a natural-philosophical view of complex and hierarchical concausality. Thus, as we saw in this work, it is understood that something is casual only for a high ontological level, when it does not fully control the causal links with respect to its lower level. Thus chance, although it intervenes in corruptive processes and is manager to a certain extent responsible for physical evils, can also favour the emergence of positive novelties. It is, then, a subject of disorder very proper to material contingency which has a definite meaning in the framework of physical concausality.

From religious faith we know that God hears the prayers of the faithful and disposes of things in a way that is not intuitive for us when he is invoked to bring about some favourable alteration in the course of events. Such intervention cannot consist of a special preparation of initial conditions in the remote cosmic past, thesis deterministic today implausible. Divine interventions in contingent physical events, for example, to protect in a journey, to favour a meeting staff , to stimulate the imagination of a person, respond to God's plans and, leaving aside the miracles, they take the form of a multitude of favours that divine Providence grants to human beings when they ask for them, or they arise from God's initiative. They are not normally manipulable or verifiable, and are therefore accepted in an atmosphere of faith and trust in divine protection. Such aids may be lacking and then things develop according to their natural causes, without further ado, although such causes are obviously also subject to God's supreme creative causality. To imagine that these interventions of God's special providence are effected by quantum alterations or by a supply of information "from above" is not unreasonable, but it is hypothetical. If humans are capable of altering physical things with their freedom, God cannot be "forbidden" to do the same, in a higher way.64.

Whether evolution, with its indeterminate course, to a certain extent, needed some special divine interventions to take a certain direction, is something we cannot know. It is normal to look for natural explanations of physical processes (emergences, potentialities, possible natural directions, favourable circumstances, predominance of the best by natural selection), knowing that at final all that comes from the Creator, and we feel a certain repugnance to multiply ad hoc special divine interventions for events that may be the result of natural causes unknown to us. Personally I tend to think that the contingency of physical processes compatible with evolution can be explained by natural causes and would not require "special" providential actions. The marvellous co-ordination of independent events, such as the fine-tuning of which the anthropic principle speaks, could be explained by the divine ordination of God the Creator, as posited in the Thomistic fifth way to argue for the existence of an intelligent Creator. One could also argue for the existence of an intrinsic finalism in the cosmos, not a vitalist one, as Leonardo Polo does when he alludes to the immanent final cause of the universe that completes the order of the cosmos and precisely makes it a cosmos that is not fully actual, but open and potential.65.

Strictly random phenomena, such as chance encounters, whether favourable or unfavourable, are caused by God as the First Cause who wills a world with coincidences. If, moreover, God wishes to intervene especially to bring about certain specific chance events, which would then not really be chance, he is free to do so, and not on a whim, but for reasons that respond to his providential plans, for example, to protect those who invoke him with their prayers....66.

These plans are general for the whole of humanity, or for groups (e.g. nations, etc.), or for individual persons. They are not scattered or saltatory, and they receive much light if we turn to the theology of faith, thanks to which we know more concretely the divine plans of salvation, such as the incarnation of the Word of God (Jesus Christ).

God has created a contingent world in which he can intervene with ample freedom, respecting natural laws and with purposes oriented to the good of human persons, who are dear to God more directly than anything else in nature. In this way the Creator concurs with human intentions and projects, and it is wonderful that this is so. Nature is rigorous, but not absolute. It is not reasonable to think of a physical universe completely Closed to the action of God that transcends what the physical laws give of themselves, when man himself organizes things, with art and technique, in a way that goes beyond what the physical laws dictate. The uncertainty and the dangers implied by the chance present in human life in its attention with things and others allows, among other positive aspects, that God acts in favor of the human being in a context of trust. Chance, with its risks, is a wonderful and positive reality in nature and in history.

64 . Something analogous can be said of the intervention in human life and even in physical events of angelic spirits, as attested to by religious faith and Sacred Scripture.

65 . Cf. knowledge and the physical world in Leonardo Polo, 2020, cit.

66 . Cf. A. M. Griffith and A. Naraghi, Randomness and God's Providence: Defining the Problem(s), academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/40836976/Randomness_and_Gods_Providence_Defining_the_Problem_s_Abrahamic_Reflections_on_Randomness_and_Providence_Kelly_James_Clark_and_Jeffrey_Koperski_eds_Palgrave_forthcoming.

Alvira, R., Casus et fortuna en Santo Tomás de Aquino, "yearbook filosófico", 1977 (10), 27-69.

Aristotle, Physics. Usual editions.

Aquino, J., I. Silva, Can emergent evolution that includes elements of chance refer to a Creator God? in C. Vanney and J. F. Franck (eds.), Determinism or Indeterminism? 2016 (see below under C. Vanney).

Artigas, M., Filosofía de la naturaleza, Eunsa, Pamplona 1998 (4th renewed ed.).

___, La mente del universo, Eunsa, Pamplona 1999.

Baelz, P., Prayer and Providence, SCM Press, London 1968.

Barbour, I., Issues in Science and Religion, Harper Torchbooks, Harper&Row, N. York 1996.

___, Indeterminacy, Holism and God's Action, in T. Peters and N. Hallanger, God's Action in Nature's World, Ashgate, Aldershot (England) 2006, 113-128.

Bartholomew, D., God of Chance, SCM Press, London 1984.

___, God, Chance and Purpose, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008.

Brock, S., Sulla causalità della preghiera di petizione: C. S. Lewis, Peter Geach e Tommaso d'Aquino, "certificate Philosophica", 23 (2014), 79-88.

Collado, S., Panorámica del design inteligente, "certificate Philosophica", 17 (2008), 17-42.

Congiunti, L., Ordine naturale e caso secondo Tommaso d'Aquino, "Espiritu", 2017 (66), 303-323.

Dodds, D., Unlocking Divine Action, Catholic University of America Press, Washington 2012, 109-113.

Durand, E., Évangile et Providence, Cerf, Paris 2014.

Edwards, D., How God acts, Fortress Press, Minneapolis 2010, 57-75.

Ellis, G., Ordinary and Extraordinary Divine Action, in J. R. Russell, N. Murphy, A. R. Peacocke (eds.), Chaos and Complexity, Vatican Observatory Publications, Vatican City State, and The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences (Berkeley, California), 2007, 359-395.

Griffith A. M., A. Naraghi, Randomness and God's Providence: Defining the Problem (s), academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/40836976/Randomness_and_Gods_Providence_Defining_the_Problem_s_Abrahamic_Reflections_on_Randomness_and_Providence_Kelly_James_Clark_and_Jeffrey_Koperski_eds_Palgrave_forthcoming

Johnson, E., Does God play dice? Divine Providence and Change, "Theological Studies", 57 (1996), 3-18.

Kahm, N., Divine Providence in Aquinas's Commentaries on Aristotle's Physics and Metaphysics, and its relevance to the question of evolution and creation, "American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly", 2023 (87), 637-656.

Kojonen, R., Is classical science in conflict with belief in miracles? Some bridge-building between philosophical and theological positions, in R. J. Russell, J. M. Moritz (eds.), God's Providence and Randomness in Nature: Scientific and Theological Perspectives, 2019 (see below), 205-234.

Maldamé, J. M., Création et Providence, Cerf, Paris 2006, 146-148.

___, Création par evolution, Cerf, Paris 2011, 215-232.

Minecan, A. M., Chance as a positive space of indeterminacy in the Thomistic assimilation of Aristotle's physics, "Areté" (30) 2018, 271-287.

Murphy, N., R. J. Russell, W. R. Stoeger (eds.), Physics and Cosmology, Scientific Perspectives on the Problem of Natural Evil, Vatican Observatory Publications, Vatican City State, and The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, Berkeley (California) 2007.

Murphy, N., Divine action in the natural order, in Chaos and Complexity, 2007 (see above in G. Ellis).

Peacocke, A., Creation and the World of Science, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1979, 103-104.

___, Paths from Science towards God, Oneworld, Oxford 2001.

___, Chance and Law in irreversible Thermodynamics, Theoretical Biology, and Theology, in Chaos and Complexity, 2007 (see above in G. Ellis).

Polkinghorne, J., Quarks, Chaos and Christianity, Crossroad, N. York 1997.

___, Science and Providence, Shambala Pub., Boston 1989.

Pollard, W., Chance and Providence, Scribner, N. York 1958.

Polo, L., Obras completas, Curso de teoría del knowledge, 4 vol., Eunsa, Pamplona 2015-2019.

Russell, R. J., Cosmology. From Alpha et Omega, Fortress Press, Minneapolis 2008.

___, Divine action and quantum mechanics. A fresh assessment, in R. J. Russell, Ph. Clayton, K. Wegter-McNelly, J. Polkinghorne (eds.), Quantum Mechanics, Vatican Observatory Publications, Vatican City State, and The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, Berkeley (California) 2007, 293-328.

Russell, R. J., W. R. Stoeger, G. Coyne (eds.), Physics, Philosophy and Theology: A Common Quest for Understanding, Vatican Observatory, Vatican City State 1988.

Russell, R. J., N. Murphy, W. R. Stoeger (eds.), Scientific Perspectives on Divine Action. Twenty Years of Challenge and Progress, Vatican Observatory Publications, Vatican City State, and The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, Berkeley (California), 2008.

Russell, R. J., J. M. Moritz (eds.), God's Providence and Randomness in Nature: Scientific and Theological Perspectives, Templeton Press, West Conshohocken (PA) 2018.

Sagrada Biblia, Qohelet, in Antiguo Testamento, Libros poéticos y sapienciales, Eunsa, Pamplona 2001; Mateo y Hechos de los Apóstoles, Nuevo Testamento, Eunsa, Pamplona 2004.

Sanguineti, J. J., La filosofia del cosmo in Tommaso d'Aquino, Ares, Milan 1986.

___, Creazione ed evoluzione. Che cosa direbbe oggi Tommaso d'Aquino nei confronti dell'evoluzione? in S.-T. Bonino and G. Mazzotta (eds.), Dio creatore e la creazione come casa comune, Urbaniana University Press, Rome 2018, 155-168.

___, Can the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas be compared with modern science?, "Studium. Filosofía y teología", Tucumán (Argentina), vol. 23, n. 45 (2020), 103-126.

___, knowledge y mundo físico en Leonardo Polo, Sindéresis, Madrid 2020.

___, Azar y contingencia, in Scritti filosofici, Edusc, Roma 2020, 1261-1272.

Saunders, N., Divine Action and Modern Science, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2002, 94-126.

Silva, I., Providencia y acción divina, in Diccionario Interdisciplinar Austral, C. E. Vanney, I. Silva and J. F. Franck (eds), URL: http://dia.austral.edu.ar/Providencia_y_acci%C3%B3n_divina, 2017.

___, Revisiting Aquinas on Providence and rising to the challenge of Divine Action in nature, in The Journal of Religion, 94 (2014), 277-291.

___, Providence, contingency, and the perfection of the universe, "Philosophy, Theology and the Sciences", 2 (2015), 137-157.

Silva, I., S. Kopf, Divine and Human Providence: Philosophical, Psychological and Theological Approaches, Routledge, N. York 2020.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologiae; Summa contra Gentiles; In Physicorum. Usual editions.

Vanney, C., Is quantum indeterminism real? Theological implications, "Zygon. Journal of Religion and Science", 50 (2015), 736-756.

Vanney, C., J. F. Franck (eds.), ¿Determinismo o indeterminismo?, Logos, Universidad Austral, Rosario (Argentina) 2016.

Ward, W., God, Chance and Necessity, Oneworld, Oxford 1996.

Juan José Sanguineti

Professor Emeritus of Philosophy of knowledge of the School of Philosophy of the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, Rome; professor at the high school of Philosophy of the Austral University, Pilar, province of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

For further information, please contact

Date and time: Friday, September 24, 2021, at 12:30 pm.

Place: classroom ICS - Siemens Gamesa. Building Institute for Culture and Society. University of Navarra. Pamplona