August 31, 2016

Tudela's workshops: architecture, visual arts and decorative arts

Crucible of the arts. Learning and workshops in the Baroque Tudela

Dr. Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

El tema de los aprendizajes y, por ende, del funcionamiento de los talleres en la Tudela de los siglos XVII y XVIII está por hacer, si bien es posible realizar algunas reflexiones y obtener algunos datos interesantes a tenor de los estudios ya publicados sobre arquitectura, escultura y pintura.

En primer lugar hay que llamar la atención acerca de las fuentes para rehacer el funcionamiento de los talleres que son básicamente todo lo relativo a las ordenanzas gremiales de la hermandad de San José de 1642 y 174, los contratos de aprendizaje, algunos pleitos de diversa índole y, sobre todo y en el caso de Tudela, por haberse conservado, los libros de matrícula parroquiales en los que se recogían las almas de comunión de los distintos hogares y naturalmente constan todos los aprendices del maestro anualmente. Esta última fuente, escasamente utilizada por los historiadores del arte, nos sirvió para reconstruir la casa-taller de Vicente Berdusán.

A lo largo de los siglos del Barroco en Tudela, como en el resto de los talleres peninsulares, la carta de aprendizaje constituyó la forma habitual de acceder al gremio y a la profesión a través del examen de maestría. Mayor dificultad plantea el hallazgo de los contratos, dado que los hijos que aprendían con sus padres no suscribían contrato alguno y la mayor parte de los mejores retablistas pertenecían a los clanes familiares de los Gurrea, Serrano, San Juan, Gambarte y del Río.

El procedimiento para firmar la escritura de aprendizaje repite el conocido planteamiento del padre o tutor del joven, que asienta a este último con un maestro para que le enseñe el oficio sin ocultarle cosa ni secreto alguno. Por su parte el joven no podría ausentarse y si lo hacía podría ser buscado, debiendo pagar el padre o tutor una cantidad por cada día que estuviese el aprendiz ausente. Obligación del maestro solía ser el proporcionar un “vestido entero como se acostumbra”, frecuentemente en el día del examen que facultaba al discípulo para ejercer la profesión. El periodo de aprendizaje oscilaba entre los cinco y los siete años, aunque lo más usual son los cinco años. En algunas ocasiones, los recién nombrados maestros quedaban trabajando en el taller de los viejos maestros. Por ejemplo Francisco de Charri, vecino de Marcilla, firmó su carta con el escultor Pedro Domínguez en 1657 por el periodo de cinco años, Juan Lafuente con el escultor José Serrano en 1683 por cinco años y Juan de Peralta se asentó por siete años con Francisco San Juan en 1685. La edad de los jóvenes aprendices solía rondar los dieciséis años y, aunque no se suele especificar este extremo en la mayor parte de las escrituras que hemos manejado, lo hemos comprobado por declaraciones posteriores en bastantes casos.

Un ejemplo de taller con datos extraídos de los libros de matrícula nos lo proporciona el caso del escultor Francisco Gurrea, localizado junto a la iglesia del Carmen en la calle Herrerías de Tudela, en el que se formaron algunos carpinteros y otros artífices que le ayudaron a llevar a cabo sus excelentes proyectos para otras tantas iglesias y conventos. Sus nombres aparecen reseñados en su domicilio familiar, en los registros de matrícula o de cumplimiento pascual de su parroquia de San Juan de Tudela. En 1682 vivían en su casa, además de la familia, Gaspar de Gambarte, José de Arnedo y Juan de Balderrín; en 1684 Pedro Casanoba, José de Arnedo, José de Lara y Francisco del Río; en 1685, los mismos; en 1687 Fermín de Arregui, Antonio Casanoba, Agustín Pérez y José Navarro; en 1688, los mismos; en 1689 Agustín Pérez, Francisco Martínez, Bautista Ricondo y José Navarro; en 1692 Agustín Pérez, Juan Zapater, Antón Castillejo y Juan Estaregui; en 1693 Agustín Pérez, Juan Pérez, Felipe Martínez, Pedro Lorea y Juan Estaregui y en 1694 Juan Pérez, Sebastián de Goicoechea, Antonio Sainz, Silvestre de Caparroso, Juan Estanga, Fermín de Baquedano y Nicolás Guelles. En 1695 Juan Pérez, Sebastián de Goicoechea, Juan Estanga, Fermín de Baquedano, Nicolás de Gili, Juan de Peralta, José Saviñán y Martín de Yrazola; en 1697 Nicolás Jili, Juan de Peralta, Juan Pérez, Martín Bidasolo y Bautista Belasco; en 1699, los mismos; en 1700 Francisco Biristáin, Felipe Caballero, Pedro Izaguirre, Juan de San Martín y Jerónimo Martínez; en 1701 Felipe Caballero, Bautista Belasco, Juan San Martín, Tomás Saldía y Jerónimo Martínez; en 1702 Bautista Belasco, Tomás Saldía, Jerónimo Martínez, Diego Lapiedra, Manuel Lobera, Lorenzo Mateo; en 1703 Bautista Belasco, Tomás Saldía, Jerónimo Martínez, Diego Lapiedra, Manuel Lobera y Juan de Montes y en 1709 Tomás Saldías Pedro Aristogorri, Juan de Aibar y Antonio Caparroso.

En el caso de Berdusán, entre las personas ajenas a la familia estricta encontramos a José Berdusán (1661, 1664 y 1665), posiblemente un tío o primo del pintor del que no tenemos noticia alguna; Francisco Crespo (1657, 1658 y 1662), Francisco Ruiz (1660-1663 y 1669), Juan de Bordas (1666), José de Villanueva (1666) y Andrés García (1691).

Diversos datos nos informan de la endogamia profesional. El taller de los Gurrea mancomunado en algunos momentos con el de Sebastián de Sola y Calahorra -casado con Francisca Gurrea y García en 1653- o la sucesión del taller del pintor Juan de Lumbier en la persona de su yerno Pedro de Fuentes y el hijo de éste último José de Fuentes.

The brotherhood and guild of St. Joseph of carpenters and masons had its chapel in the cloister of the collegiate.

In 1697 they ordered the sculptor Juan Biniés and the gilder Francisco de Aguirre to make the group de los Desposorios with its corresponding altar.

(Photo: Catalog Monumental de Navarra)

A reflection on workshops and altarpieces

In 1995, Professor Pérez Sánchez, in a study on the altarpieces of the Community of Madrid, spoke about the "problem not completely solved regarding the paternity of the altarpieces". With this he alluded to the many questions raised by the construction of the great genre par excellence of our Baroque, because the contract and the appraisals together with the accounts give us something to know, but not everything about how many masters and/or apprentices were involved in the whole, or other ways of contracting that did not necessarily mean going through the notary to formalize the writing. In general, a master with a workshop contracted, committed himself, gave bonds and received payments; he designed, directed the workshop and if he considered it necessary or convenient, he associated with other masters and workshops.

Very special cases provide us with very special data about the issue of people involved in the construction of some altarpieces. In the case of the main altarpiece of the parish of San Miguel de Corella, we know that the master Juan Antonio Gutiérrez, who had no workshop, was in charge of the work and selected a series of journeymen whom he knew and therefore trusted work. Thus, we know from data published by Arrese that they participated in its construction: Juan Antonio Gutiérrez, as manager of project , received a salary of 10 reales a day and employed the following artisans in the altarpiece, ranked in order of salary: Pedro Onofre Coll, with seven and a half reales, as sculptor, José Andrés and Manuel Ugarte, with five reales; Juan Aibar, Pedro Peiró, José Zabala, Francisco Rey and Salvador Villa, with four reales; Martín de Lizarre, José Oraa, José de Aguerri, Francisco Tudela, José de la Dehesa and Manuel Abadía, with three reales the young Diego de Camporredondo, with two and a half.

Although it is not a Navarrese case, the case of the altarpiece of the Immaculate Conception of the cathedral of Calahorra, made between 1736 and 1737 under the munificence of Don Juan Miguel Mortela, is even more significant. The following fourteen artisans worked on it by specialties, namely: an architect-tracer who was in charge of project for two hundred and sixty-six days with a salary of six and a half reales a day, under whose orders were: three sawyers, two assemblers, three carving cleaners, two carvers and a sculptor with two collaborators. These are very interesting data that can give us an idea about the equipment that was needed for the construction of those powerful machines of wood architecture.

We will add that in the case of the main altarpiece of Falces, contracted with the master Francisco Gurrea from Tudela on January 29, 1700, we know that it was assembled between August 16 and September 16, 1703, the latter date on which "the patrons were satisfied with it and, recognizing that they had exceeded the master's expectations, gave him a hundred reales of eight and fifty robos of wheat in gratitude, as well as seven officers at four pesos to each one....... of which both were very pleased". This subject of data escapes the history of our altarpieces and helps us to better understand their reality.

There was no lack of occasions for the association of masters. Thus we know that for the realization of the altarpiece of the chapel of the Holy Spirit in the cathedral of Tudela, José Domínguez, Francisco Gurrea Casado and Sebastián de Sola y Calahorra joined together in 1659.

In relation to the great development of the Solomonic altarpieces with paintings in their compartments, something that was possible thanks to the presence in the capital of La Ribera of Vicente Berdusán, the case of the main altarpiece of Funes, contracted with Sebastián de Sola y Calahorra and José Domínguez in 1664, is very significant. In one of its clauses we read: "that the official who is left with the said work has the obligation to paint all the panels at his own expense, with the condition that Vicente Verdussán is to do it, because he is fully satisfied with it. And in case the said Vicente Verdussán dies, it is left to the choice of the patrons to give the painting to the officer they want at the cost of the officer who remains with the work".

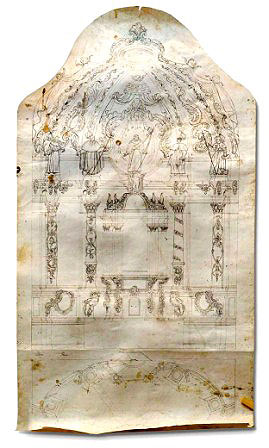

Original parchment tracing of the disappeared altarpiece of the Poor Clares of Tudela, work of the del Río brothers.