Photographs of rural life in Navarre at the beginning of the 20th century

IGNACIO MIGUÉLIZ VALCARLOS

The growing research on photography in recent years is gradually bringing to light private collections that had hitherto received little interest or importance. In this framework we must contextualise two private collections and the photo library of the Capuchins of Pamplona, which preserve images that cover the main themes of this art form, from scenes of daily and intimate life to official and public events, as well as photographs of popular types, landscapes, and urban and architectural views. From among the holdings in these collections, we are going to focus on some interesting images from subject that depict rural life and farm work in Navarre in the first decades of the 20th century.

Following the emergence of photography, several themes developed, most if not all of them strongly influenced by those depicted in the paintings of the time. One of them is the photography of genre scenes and popular types, one of the main variants of which is that of scenes linked to the rural world: landscapes, farm work, portraits of peasants, animals, etc., images that are linked to the vision of man linked to nature and to the origin of the world, as well as to the rectitude of customs and morals. As a result, many professional and amateur photographers turned their eyes to this world and used their cameras to portray traditions and customs, as well as the people who represented them. In Spain, these images can be related to the authors of the Generation of '98, who depicted these same themes in their work, which continued throughout the first half of the 20th century, as can be seen in photographers such as José Ortiz Echagüe and the Marquis of Santa María del Villar. These themes continued throughout the century, but with other implications and meanings. During the Civil War the image of the peasant was used for political and propagandistic purposes; in the second half of the century it became important in the reports produced by documentary photographers; and nowadays many contemporary authors have included it in their work, although with a different perception, often linked to a documentary nature within press reportage.

José Ortiz Echagüe. Mayors of Garralda.

The rural world meant a return to the origins of civilisation and the communion between man and nature. The Romantic landscape painters had already experienced this change; in contrast to reason, the return to nature meant a connection with creation and divinity, far removed from the intervention of the hand of man. As a result, this theme developed strongly during Romanticism in the field of painting, first linked to the landscape topic and later to genre scenes, subject , which was particularly popular in Spain development, although it was more closely linked to a folkloric image of our country. After the advent of photography, these themes were also adopted by this new art form, especially by the pictorialist trend. Many photographers would capture with their cameras a rural costumbrismo, the world of the peasantry, generally associated with an idealised and stereotyped vision of popular affairs, as Joan Fontcuberta pointed out in the exhibition Imágenes de la Arcadia, linked to an imaginary of a new Arcadia, of a harmonious and pleasant world linked to the lost paradise.

Similarly, the rural world continued to have an exotic and idealised character for all those who came from urban environments and were attracted by popular traditions and customs. In fact, in the second half of the 19th century, études de après nature became fashionable, images taken from nature which, in addition to attracting the urban public, were used by many painters to depict this theme in their works at model . The relationship between this urban and rural public was favoured by the fact that in the second half of the 19th century it became fashionable to go to the countryside, to nature, mainly in the summer season, partly because of medical recommendations that recommended fresh air and a temperate climate, as well as thermal baths and "wave" baths in the sea, which led the upper classes in Spain to turn their gaze towards the Cantabrian coast. Thus, summer villas and mansions were mixed with farmhouses and farm workers' houses, both on the coast and inland, creating a communion between the two worlds. The Spanish wealthy classes, as well as enjoying a beneficial climate, lived with farmers and farm workers in the rural environment, crossing their paths during their walks, seeing them working on the agricultural part of their properties or buying supplies for their homes. As a result, they forged a certain familiarity and relationship with farmers, labourers and shepherds, as well as with the environment in which they lived, which allowed them to capture it with their cameras as amateur photographers.

In the approach of these images, the idea of a return to nature and the origin of man, which philosophers such as Heidegger were advocating as the ideal of life, linked to the simple, traditional and virtuous, is maintained. In a certain sense, the working classes of the rural world were looked upon with envy, as they enjoyed and benefited from this pure and innocent spirit, in a life in close contact with nature at contact plenary session of the Executive Council .

At the same time, the depiction of peasants and characters linked to the rural world was part of the tradition of depicting popular types that was so prevalent throughout the nineteenth century, and which had its roots in the previous century and lasted until the twentieth century. Thus, we can trace a timeline of representations of popular Spanish types, which reflect the ethnographic wealth existing in Spain, from the engravings of Juan de la Cruz Cano y Olmedilla to the images of José Ortiz Echagüe, and including the types of Jean Laurent. These images depicted the popular types of each region, albeit taken in different ways; either captured in their daily and habitual chores, out of sight of the camera's gaze, or portrayed in their traditional costumes in carefully studied poses and compositions. It was these images that served as model and inspiration for these amateur photographers to capture the same subjects with their cameras, aided by the fact that at the same time they were photographing their environment and the landscapes, both physical and human, with which they lived. And let us not forget that, given the curiosity of the human being and the social customs of the time, these photographs were often used, as they are today, for recreational viewing in times of leisure or to show to family and friends on their return to the city.

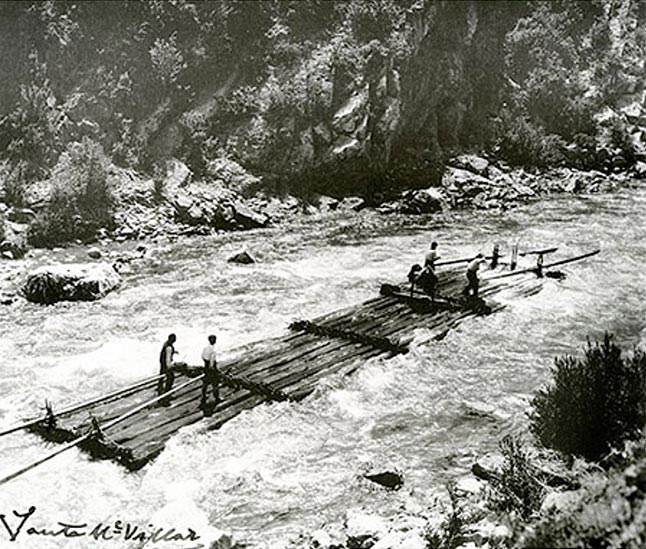

Diego Quiroga y Losada, Marquis of Santa María del Villar. Almadía on the Esca.

Many programs of study and professional photographers took up genre scenes, the rural world and popular types with their cameras, making their imagery available to those who could not travel and imbibe this world through their images. In the beginning, the photographic programs of study opened in towns and cities, and the props - made up of false rocks, bushes, bushes and other types of vegetation, rustic wooden parapets, etc. - were set up to recreate rural scenes and contextualise them.- This was sometimes complemented by a peasant costume in which the sitter was disguised, while at other times this setting clashed with his image, elegantly dressed in the latest fashions. When, thanks to technical advances in the field of photography, especially after the appearance of wet collodion, photographers were able to go outdoors, there was a succession of natural photographs, the études de après nature, as can be seen in reports by numerous photographers, such as the one by José Roldán of the popular types of the Roncal in 1900. In these photographs, and depending on the photographer's interest, we can see either close-up portraits that capture both the psychology and the clothing of the person portrayed, or more open shots, in which, as well as seeing subject , we can appreciate the environment and the context in which they are located, in a study of their customs and traditions.

Alongside these professional photographers, we will go to attend to see the emergence of the amateur photographer who, equipped with a camera, would more or less accurately capture all the images of interest to him or her. The proliferation of these photographers was brought about by the appearance of the dry gelatin-bromide plate and compact cameras. Thus, in 1871 Richard Leach Maddox (1816-1902) introduced dry gelatin plates, which were improved in 1878 by Charles E. Bennet (1840-1927). This technique, which shortened the time of exhibition to a quarter of a second, made it possible to approach the concept of the "photographic snapshot". As the name suggests, the fact that the emulsion was dry meant that the plates could be used long after their manufacture, which also favoured their industrial production. These were glass plates sold in boxes, already prepared with gelatin-bromide emulsions, which had to be opened and placed in the camera frame in dimly lit rooms or spaces. Once used, it was not necessary to print them immediately, but they could be developed afterwards, which gave the option of taking photographs far from the studio, without the need to carry a laboratory with you. These plates were of uniform format, of various sizes, with glass of regular sizes and edges, cut in an industrial way. The commercialisation and stability of this procedure made it possible for many amateurs to enter the world of photography, who no longer needed to prepare these negatives themselves, but bought them from commercial establishments ready for use. This technique had the advantage of offering sharp and contrasted images, almost instantaneous, as it shortened the time of exhibition of the shot and did not require the images to be captured to be still, which widened the subject field.

A variant of these plates were the stereoscopic ones, which used a binocular camera, with two lenses with the same focal length, thanks to which two very similar snapshots were obtained, with a slight deviation of the visual axis. When looking at the two resulting shots at a certain distance, and with the appropriate viewfinders, both images were seen at the same time, superimposing one shot on the other, which gave the sensation of seeing it in three dimensions in a very similar way to how the human eye would see it. An important milestone in this technique was the invention by Jules Richard (1848-1930) in the eighties of a new system for capturing these images, with the employment glass plates of 4.5 x .7 cm that were positivized by contact on glass plates of the same dimensions, mirroring the motifs, that is, inverting them from right to left. This system was very versatile and of small dimensions, especially practical for use by amateur photographers. Despite the small size of the plates, the resulting images were extraordinarily sharp, capturing every detail in minute detail.

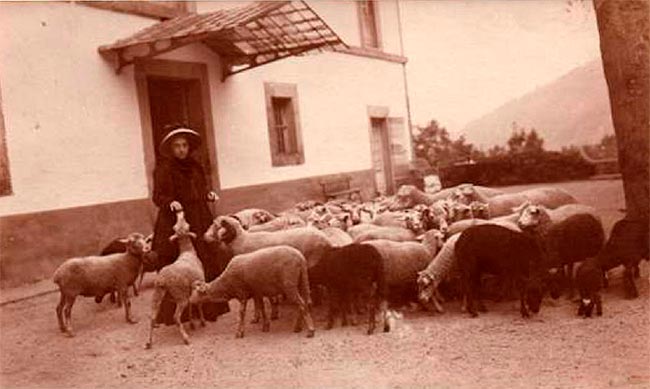

In this way, and thanks to advances in photographic techniques, all those amateur photographers were able to acquire a camera with which to photograph the scenes and people around them, as we can see in the photographs presented here; images that follow the themes of the rural world, taken with a naïve candour and without the care in the composition of the shot that we see in professional photographers. On the contrary, many of these photographs present an anecdotal composition, sometimes with errors in the framing and composition, including in the definition of what is being photographed, but which capture a bucolic world in a pure and innocent manner. Among the different images preserved we find a variety of themes: landscapes, compositions with animals or farm work and popular types that reflect the interest in the rural world that was experienced at this time. Let us not forget that what may seem an anodyne and uninteresting image can be an escape route to the imagination for a man of the city. In this sense, the image of a lady interacting with a flock of sheep outside the door of a house almost as if they were domestic animals to be petted is paradigmatic.

Anonymous. Lady with flock of sheep.

The landscapes show bucolic and beautiful views, not without a certain picturesqueness, of that Arcadia to which we want to return. They include general views, with a wide framing, in which in most of the images there is no horizon line, which is generally cut off by the presence of a mountain that delimits and serves as a backdrop to the landscape sample. There is nothing in them that makes them worthy of being immortalised, they are not sublime, they are anodyne, beautiful but normal, so that their capture can only be due to the interest that a city dweller may feel in these landscapes which are unusual for him, which are environments to which he is not accustomed.

Anonymous. Landscape.

Anonymous. Landscape.

Anonymous. Landscape.

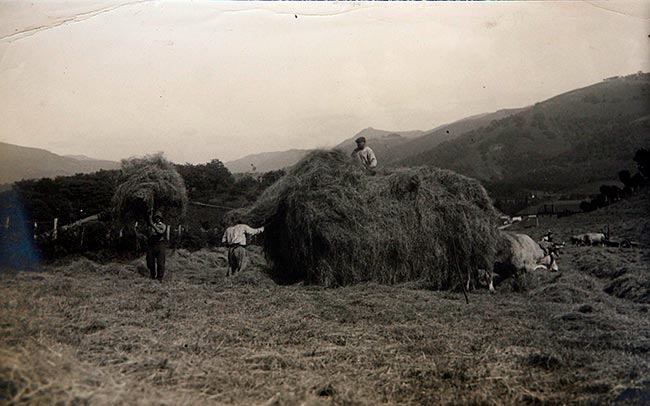

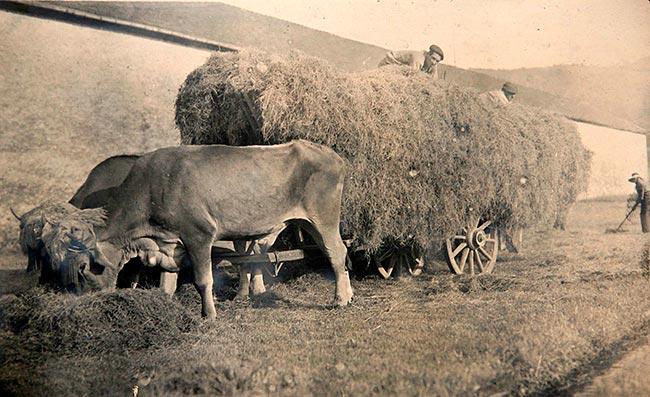

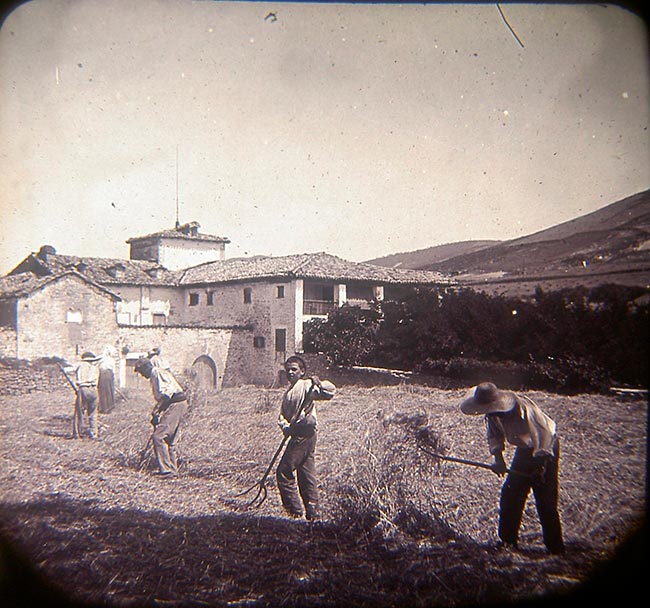

It is curious that most of the images of farm work in these collections refer to flocks of sheep grazing or the work of harvesting crops, indicating that they were taken in the summer, when the wealthy classes were leaving the cities and moving to properties in the countryside. Meanwhile, the images showing peasants can be divided into those showing them at work, dressed in the clothes of work, and those showing them at times of relaxation, leisure and celebration. Among the latter, we see popular types from the Roncal region, which is one of the main points of interest for photographers in Navarre, as we have images of the same types by photographers such as José Roldán, the Marquis of Santa María del Villar and José Ortiz Echagüe. It should be noted that in most of the images in which the human figure appears - both those of peasants carrying out their daily tasks and those in which they are seen at moments of rest, mainly after religious services - the shots are taken from a distance. The photographer does not approach these people, but rather captures them from a certain distance, and generally with the people portrayed unaware of the photographer's presence; although there are also others in which these figures pose, surprised and surprised, for the photographer.

Anonymous. Farm work.

Anonymous. Farm work.

Anonymous. Farm work.

Anonymous. Farm work.

Anonymous. Farm work.

Anonymous. Farm work.

Anonymous. Farm work.

Anonymous. Farm work.

Anonymous. Farm work.

Anonymous. Peasants.

Anonymous. Roncaleses.

Anonymous. Departure from mass.

Anonymous. Departure from mass.

Anonymous. Departure from mass.

Finally, the photographs of animals show us the photographer's interest in their figures, portraying them in the foreground, in closer frames than those used for the human figure, sometimes we might even think in a reckless manner. This framing subject indicates the photographer's curiosity about them, as if they were something totally unknown and surprising that he wanted to immortalise with his camera in order to capture their corporeality. Sheep and goats, isolated or in herds, oxen and chickens, are photographed only for the sake of having tangible representations of what they are like, not for the artistic aspect they might give to the image. We even see several photographs devoted to the same flock but with different framing, taken without care or attention to composition, in some centred on the animals and in others on the shepherds, in this case children, who guide them, which seems to indicate the fascination that the topic causes in the photographer, who captures it in a hurried manner.

Anonymous. Flock of sheep.

Anonymous. Flock of sheep.

Anonymous. Flock of sheep.

Anonymous. Flock of sheep.

Anonymous. Flock of sheep.

Anonymous. Flock of sheep.

Anonymous. Flock of sheep.

Anonymous. Sheep.

Anonymous. Oxen.

Anonymous. Oxen.

Anonymous. Rooster.

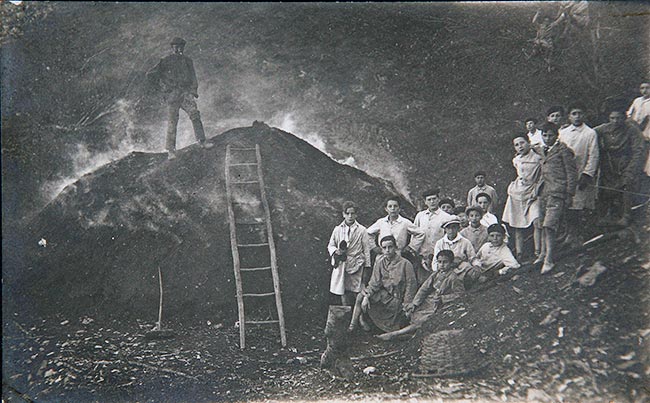

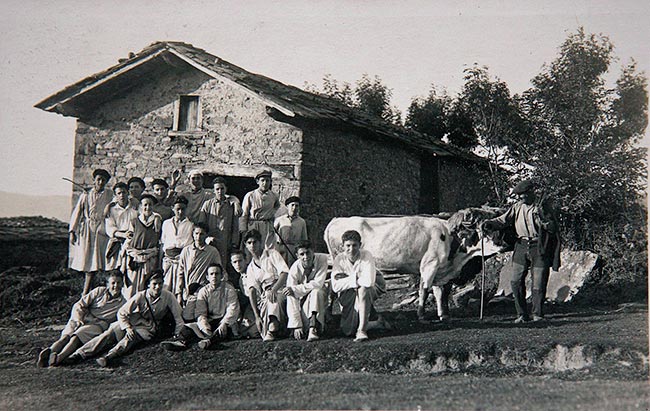

At the same time, this return to nature and to the innocence of the human being was also present in the approach educational of the Capuchin high school of Lekarotz, with an innovative methodology that attracted students from all over the peninsula to study there. The schoolchildren took part in the life of the area where the high school was located, going out to get to know the customs and traditions of the area on different excursions. In these excursions, they not only saw the way of life of the local inhabitants, but also participated in the idyllic imaginary of rural life. In this case, moreover, Lekarotz was a pioneer in the methodology of teaching, since within the different subjects taught, a series of workshops were set up to show these contents in a way internship. These workshops included a photographic cabinet, which was always headed by one of the friars, initially Friar Antonio de Antequera and later Friar Pedro de Madrid. Thanks to this photographic laboratory , both the daily life of the high school and the students' excursions were captured by the camera, thus recording the students' involvement with the rural environment in which they found themselves; thus, the visit to a charcoal pit, to an outhouse or to the work of harvesting in the fields is recorded.

Anonymous. visit to a coal bunker. 1926.

Fray Pedro de Madrid. Day in the Country. 1912.

Anonymous. Day in the Country. 1926.

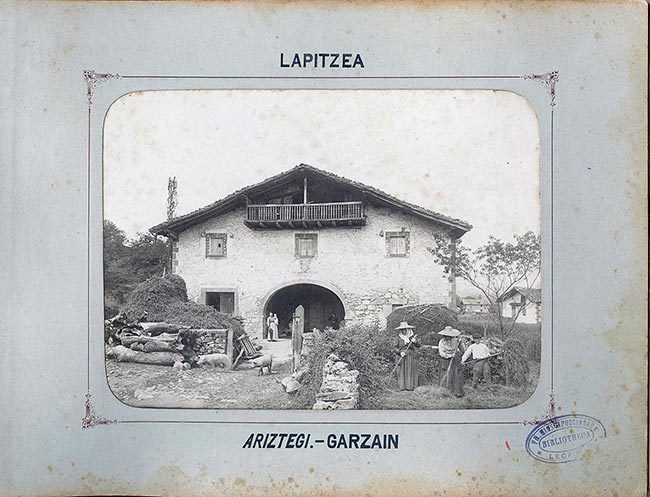

At the same time, from his studio in Lekarotz, Fray Pedro de Madrid developed a project that collected, in an extensive report, one of the main signs of identity on which the uses and customs of the rural population of the Baztán valley where the high school was located were based: the house and the farmhouse, symbol of the family. The creation of this album, in which a series of farmhouses of the Baztán were photographed, is part of the representation of the values embodied by the Basque peasantry, which are collected in a social photographic competition held in 1912. This contest was part of the acts of commemoration of the VII centenary of the battle of Navas de Tolosa, sponsored by the Government of Navarre at the request of the Commission of Historical and Artistic Monuments of Navarre, within the VI Social Week, in relation to the Catholic agrarian cooperativism and the Catholic Social Federation. Within the photographic competition there were six sections, being the third one dedicated to scenes of the work in the countryside and the fifth one to the Basque farmhouses. Fray Pedro de Madrid presented the report Etxezarra, compilation of farmhouses of the Baztan, with which he won the first award of Basque farmhouses and the first special award for amateurs. This report did not go unnoticed, and several institutions requested copies of it, both to keep in their photo libraries, such as the Commission of Historical and Artistic Monuments of Navarre or the Municipal Museum of San Sebastian, and to illustrate different publications, such as the Catalog Monumental and Artistic of the Province of Navarre.

Fray Pedro presented an album to competition that included 24 of these farmhouses, although snapshots of many others are kept in the Capuchin photographic collection at file in Pamplona, where the Lekarotz photographic collections were kept. The glass plates with the original negatives are also kept, in which we can see images of which we do not know any positive copies. In these photographs the points of view and the distance of the frame alternate, as well as the presence or absence of the human figure. In some we see only the house, while in others we see the inhabitants in front of them, either posing alone or with their animals, or carrying out some of the tasks typical of peasants. In this case, the images of the farmhouses acquire prestige and solemnity, as they reflect one of the main signs of identity in the valley, the assimilation of the family with the house, so that what is represented is not only a building, but also the perception of the identity of the family in the social environment in which it is located.

Fray Pedro de Madrid. Lapitzea. Ariztegi-Garzain. 1912.

Fray Pedro de Madrid. Etxezuria. Amaiur. 1912.

Fray Pedro de Madrid. Bizarrenea. Azpilcueta-Arribiltoa. 1912.

Fray Pedro de Madrid. Farmhouse. 1912.

AZANZA LÓPEZ, J. J. and SAN MARTÍN CASI, R., "Casa, familia, heredad. La colección fotográfica de caseríos vascos de Fr. Pedro de Madrid. 1912",Revista de Dialectología y Tradiciones Populares, vol. LXVIII, n.º 2, Madrid, committee Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2013, pp. 385-422.

AZCONA, T. de, "La fotografía en el high school de Lecároz (Baztán)", in FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R. (Coord.), Fotografía en Navarra: fondos, colecciones y fotógrafos, Pamplona, Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, 2011, pp. 397-414.

CÁNOVAS, C., Navarra / Fotografía, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 2012.

CRUZ CANO Y OLMEDILLA, J., Colección de trajes de España, tanto antiguos como modernos, Madrid, M. Copin, 1777.

DOMENCH, J. M.ª and AZPILICUETA, L., Navarra en blanco y negro, Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 2000.

DOMENCH, J. M.ª, Navarra, hombres y tierras, Pamplona, Fundación Caja Navarra, 2004.

DOMEÑO MARTÍNEZ DE MORENTIN, A., La fotografía de José Ortiz-Echagüe: técnica, estética y temática, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2000.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R. (Coord.), Fotografía en Navarra: fondos, colecciones y fotógrafos, Pamplona, Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, 2011.

FONTCUBERTA, J., Imágenes de la Arcadia, Madrid, Library Services Nacional, 1984.

LATORRE IZQUIERDO, J., El fotógrafo Santa María del Villar y Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2005.

LATORRE IZQUIERDO, J., Santa María del Villar, fotógrafo turista, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 1999.

MIGUÉLIZ VALCARLOS, I., "Fotógrafos navarros en la colección fotográfica del marqués de la Real Defensa", in FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R. (Coord.), Fotografía en Navarra: fondos, colecciones y fotógrafos, Pamplona, Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, 2011, pp. 217-260.

MIGUÉLIZ VALCARLOS, I., Fotografía navarra. La colección del marqués de la Real Defensa, Tafalla, Fundación Mencos, 2014.