Tabernacles of Navarre.

A selection of works from the medieval centuries.

AINTZANE ERKIZIA MARTIKORENA

University of the Basque Country/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea

The tabernacle has been and is a central piece of furniture in Catholicism and its liturgy because it is a receptacle destined to reserve, keep and guard the body of Christ consecrated in the mass, to be able to administer the sacrament of the Eucharist outside of it and for Christ to be permanently present in the church. As with all liturgical objects, this very sacred function has determined the form adopted, the artistic attention received and also its location within the ecclesial space. For this reason, in the long history of the tabernacle, different solutions have been adopted and very varied productions have originated, thus creating an interesting artistic typology that is necessary to study from the point of view of the history of art.

This exhibition sample together for the first time a series of works that form a little studied heritage: the medieval tabernacles of Navarre. Not all the works are analyzed in depth and it is not an exhaustive Catalog , nor does it gather all the historical documentation that informs about it. What is intended here is to expose a selection of works that, seen as a whole, make up an artistic landscape that has been blurred by history and, with this, we will try to explore their artistic importance, beyond their liturgical relevance.

Although degree scroll refers to the tabernacles that were produced in Navarre during the medieval centuries, it is necessary to make a chronological precision. As is well known, the Age average is a very long and complex period to analyze, and as far as tabernacles are concerned, there are practically no known examples until the 13th century. On the other hand, the typologies of tabernacles created in the average Age crossed the 16th century and lasted until the last decades of this long century, specifically until the implementation of the new decrees emanating from the Council of Trent, which was a milestone in the history of the tabernacle. For this reason, the selection includes some tabernacles that are artistically Renaissance, but typologically medieval.

The Eucharist is the sacrament in which God's plan to save humanity through the sacrifice of his Son is expressed, and it is the most important of the seven sacraments. After declaiming at the consecration of the Mass the words pronounced by Christ at the Last Supper, the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ, by virtue of the doctrine of transubstantiation. This dogma was proclaimed at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, after several centuries of controversy and after scholasticism had closed the theological discussion. From that moment on, the Church reinforced the dogma with a series of rituals designed to show it, such as the elevation of the host at Mass, the ringing of bells at the consecration, the incensation of the Eucharist, genuflections and other signs, as well as the creation of the feast of Corpus Christi, celebrated for the first time in Liege in 1246 and instituted by Urban IV in 1264. In this Eucharistic fervor, Eucharistic miracles proliferated and confraternities dedicated to his devotion were created. In Navarre, the pioneering confraternities of the Blessed Sacrament of Tudela and that of the Corpus Christi, founded in the cathedral of Pamplona in 1317 by Bishop Arnaldo de Barbazán, are known.

Processional monstrance of Santa María la Real de Sangüesa. Sangüesa workshop, early 15th century with interventions at the end of the 16th century. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

All these rituals required artistic objects, and so custodians, expositors and new tabernacles of various shapes, some of them even transparent to facilitate visual communion, emerged. One of the earliest examples of medieval processional monstrance that has been preserved in Spain is precisely in Navarra. It is the monstrance of Santa María la Real de Sangüesa (fig. 1), a spectacular silver tower from the early 15th century, with later interventions, designed to exalt the Eucharist before the pious sight of the faithful. For this reason it can be affirmed that the 13th century was a fundamental milestone in the history of the tabernacle. From this moment on, tabernacles and monstrances, two closely related artistic typologies, will begin a parallel evolution, in step with artistic evolution.

Fig. 2. Eucharistic tower of the church of St. Mary in Ulm (Germany). 1460-1465. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

At the end of the Age average, in the 15th and early 16th centuries, the designs of many tabernacles in Germany reach an extraordinary level of sophistication. They combine geometric figures at different scales and with multiple couplings, feature highly complex intertwined vegetal and geometric designs, and have flamboyant finials that defy gravity and the materiality of the stone, creating an "artistic alchemy". Some specialists consider Eucharistic micro-architecture to be a genre within architecture that, moreover, has its own evolution, not always in tandem with built architecture. The tabernacle of St. Mary's Church in Ulm (Germany) (fig. 2) is one of the best examples of this artistic concept. It was executed in 1460-1465 and reaches the exceptional height of 26 meters, integrated into its Gothic space and, at the same time, outstanding thanks to its artistic ambition. In the church of St. Lawrence in Nuremberg the same is true; the Eucharistic micro-architecture executed by the sculptor Adam Kraft between 1493 and 1496 is a lesson in artistic creativity at the service of devotion to the Blessed Sacrament.

Detail of the Brabant Calendar (Brabantse uur- en kalenderwijzerplaat). Master of Louvain, ca. 1500. M-Museum Leuven (Belgium). Photo: Aintzane Erkizia.

If we move this model to Navarra, we cannot find anything comparable, neither in size nor in artistic approach. However, in their simplicity and discretion, the tabernacles of Navarre are architectural designs conceived as such and, many times, a higher quality in the idea than in the execution can be noticed in them. This means that the conception of the work is based on models of B quality and the material execution of design is in the hands of officials. This difference between design and execution is not only a contemporary appreciation. A Brabantian image from around 1500 (fig. 3) describes this artistic process when sample a tracer is designing -compass in hand- an exempt eucharistic tower of stone, while a carver or sculptor is carving the same work with chisel and hammer. Two artisans for a single work, each with his own responsibility. Therefore, it is important to understand that from the intricate and delicate design of Adam Kraft in Nuremberg to the modest execution of the tabernacle of Metauten, all these works belong to the same artistic family and, for their correct evaluation, it is necessary to estimate each of them in their particular context.

The second fundamental milestone in the history of the tabernacle is the Council of Trent (1545-1563), convened for update the Church at a time when the Protestant reforms had questioned or denied the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, among many other issues. In several sessions dedicated to the sacrament, the Catholic Church reaffirmed the Eucharistic dogma in a very emphatic way and emphasized once again the character of the Mass as an atoning sacrifice, making altar and tabernacle an indissoluble unity. To show this to the congregation, he ordered the construction of free-standing micro-buildings with a central plan, either of wood or stone, invariably placed in the center of the altar and in very visible places. The Eucharist became the liturgical and devotional axis of the Church, and the tabernacles were placed in the spatial and visual axis of the temples. This meant the systematic elimination of the medieval tabernacles, but also the creation of new eucharistic furniture such as expositors, demonstrators, baldachins and other artifacts that would experience a spectacular development in the centuries of the Baroque.

The ways used in the medieval centuries to keep the Eucharist have been the subject of some programs of study in Europe, being more numerous those made from theology than from the history of art. This is due -among other reasons- to the fact that very few have been preserved and, moreover, many of them are in a very precarious state of preservation. The European country in which medieval tabernacles have been most thoroughly studied is Germany, where the richest and most splendid works of Eucharistic microarchitecture are to be found. Other more general publications deal with the study of the tabernacle as an artistic typology in Europe, with brief but very valid information to know how many medieval tabernacles exist and what they are like.

The main stumbling block of programs of study about tabernacles in the medieval centuries is the state of preservation in which they have been preserved up to the present day. Most of them have disappeared because they were massively replaced in the last three decades of the 16th century by new tabernacles built under the protection of the renewed liturgy after the Council of Trent. Paradoxically, the most monumental and emblematic European medieval tabernacles are found in Lutheran churches, because in the Protestant Reformation they lost their sacred function, but maintained a utilitarian function. Even today it is surprising that such a strong liturgical rupture was accompanied, in many places in Central Europe, by a material continuity, perhaps motivated by its artistic value, or simply characterized by a conservative tendency. The German tabernacles of St. Mary of Ulm and St. Lawrence of Nuremberg mentioned above are in Lutheran churches. It can even be said that the best surviving 13th century tabernacle landscape in Europe is to be found in the Lutheran churches on the island of Gotland (Sweden), the only place in Europe that has preserved a group of tabernacles from this century marked by the Lateran Council.

On the contrary, in Catholic parishes, in constant artistic renovation, of the few medieval examples that have survived until today, it does not seem that there is none that is complete and in its original state and place, but we only have the fragments of a great historical shipwreck to reconstruct the Eucharistic landscape. Some Gothic tabernacles were reused to store relics, holy oils or parish books, by order of the bishopric visitor who considered that the Blessed Sacrament was not kept in a dignified manner as the times required, as we see in numerous documentary testimonies. Some of them, fragmented, have been used as the base of baptismal fonts or bases for carvings; with time they lost their function again and many ended up disappearing, even in recent times.

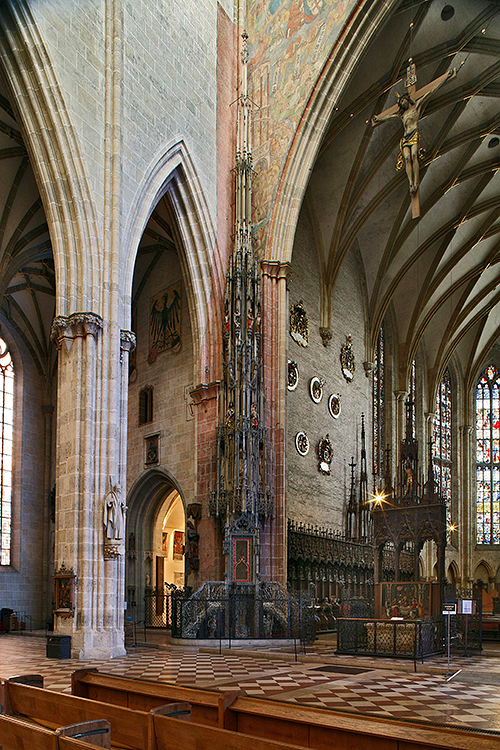

Fig. 4. Part of the chancel of the parish church of San Esteban de Genevilla. The magnificent Renaissance main altarpiece built between 1549 and 1563 hides part of the Gothic tabernacle in the wall. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

A very repeated fact both in Navarre and in the Hispanic kingdoms during the 16th and 17th centuries was the construction of large altarpieces that occupied the chancel, with their wooden tabernacle integrated into the structure and over the main altar. The construction of these enormous pieces of furniture as a backdrop for staging the liturgy hid the Eucharistic niches located on the gospel side of the chancel wall. Some of them are visible because they "peek out" from the altarpiece (fig. 4), others are uncovered when the altarpieces are dismantled, and many others are still hidden, waiting to be discovered and studied.

Another conditioning factor is that the vast majority of medieval tabernacles in Spain are located in small rural churches, in nuclei relatively far from the centers of power such as cathedrals and collegiate churches, so in principle they are not the best artistic works or the most monumental. But, in addition, little or nothing is known about the internship of the Eucharistic reservation of those places that functioned as a liturgical focus and that marked the passage of any change in the liturgy and, therefore, in the furnishings. This is due to the absence of medieval tabernacles in these centers of power and the little information provided by the documentation, but also to the lack of programs of study depth, perhaps motivated by the difficulty of their study that we are describing. In any case, searching in storehouses and sacristies of rural parishes, and rummaging through the text lines of the factory books, medieval tabernacles appear.

Throughout Europe there are documented chests placed on the altar where the Eucharist is kept and in numerous Hispanic synodal constitutions there is talk of "bochetas", "caxitas de madera", chests, arcas and arcas destined for that purpose. Thus they appear in the synodal constitutions of Valladolid of 1228, those of Santiago de Compostela of 1289 or in those of Leon celebrated in 1303, to give the oldest known examples in the Hispanic world. In this sense, Navarre does not lag behind. In Ancín, in 1541, the visitor finds the Blessed Sacrament "in a wooden chest with its lock and key on the main altar", and in Estella in 1548 he reports it as "a relic that is in the middle of the main altar". In spite of being two late quotations in chronology, we must not forget that when a visitor describes parishes in those dates, he is showing a still medieval panorama, since a few years later the visitors already ordered the removal of those tabernacles to make new ones, according to the Tridentine form.

These arks were not only utilitarian boxes, but also harbored a symbolism that goes back to the Holy Scriptures, since it alludes to the Ark of the Covenant, one of the most used Eucharistic prefigurations in medieval art. The biblical ark contained the manna, a prefiguration of the Eucharist as divine food, just as these arks do; it also represents the covenant between God and the Jewish people, just as the Eucharist is the new covenant; and the Ark materializes the presence of Yahweh himself, while the tabernacle contains the body of Christ. Hence the term 'tabernacle' - the tent in which the Ark was kept in the desert - has been employee for centuries to denote the tabernacle, and the custom of covering the tabernacle with a conopeo corroborates this.

Eucharistic chest from the monastery of Santa María la Real de Fitero. Limoges or Hispanic workshop, ca. 1220. Photo: Foundation for the Conservation of the Historical Heritage of Navarre.

An excellent Eucharistic chest from Navarre is the one from the monastery of Santa María la Real de Fitero (fig. 5). Made around 1220 in gilded copper, engraved and enameled with champlevé technique, it is an example of the typical late-Romanesque production of enameled copper pieces, made in workshops in Limoges or by some itinerant workshop that worked in Silos or Navarre itself with the same technique, models and aesthetics as the French works. The fact that it has a lock with a key gives a clue to think that it was a tabernacle, and, in addition, it must have facilitated its reuse as a reliquary since at least 1582, as can be seen in the abundant bibliography of this interesting work. It must not be by chance that in these last decades of the 16th century it is being reused to keep relics under lock and key, since it was common in tabernacles that abandoned their Eucharistic function, especially at a time when the new Tridentine wooden tabernacles were built on a massive scale.

On the other hand, the iconography of this box leaves no doubt as to its function as a tabernacle. In the main body, a Calvary accompanied by two busts -interpreted as the Old and New Testament or as the Sun and the Moon-, crowned on the lid by the relief of God the Father blessing and holding the scroll of the Law, and on the other sides, angels. As usual in sacred art, the iconography reveals the function and, in this case, presents the Eucharist as the Body of Christ who has died and risen to be the guarantee of eternal life according to God's covenant, flanked by angels on the sides and thus linking with the biblical description of the Ark of the Covenant.

Fig. 6. Pyx of Esparza de Galar. Limoges or Hispanic workshop, first half of the 13th century, Pamplona Cathedral and Diocesan Museum.

Along with Fitero we must mention the Romanesque pyx of Esparza de Galar (fig. 6), conserved in the Diocesan Museum of Pamplona. It is also a small piece of enameled copper, cylindrical and with the usual conical lid topped with a cross. It has been dated to the first half of the 13th century and attributed to itinerant enameled copper workshops. In this case the work is a small box to keep the Blessed Sacrament which, as we know, has been in use for centuries, because it is still used today, now converted into a ciborium or portaviático. The cylindrical shape with a conical lid is a constant feature of the pyxides of the High and Middle Ages average and is a clear representation of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, a shape that spread throughout Europe through medals, images and replicas of this building so important for the Church.

Fig. 7. Pyx with the Multiplication of the loaves. Sixth century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (17.190.34a), from the parish of San Pedro de la Rúa de Estella. Photo: MET.

The most splendid piece of this typology is undoubtedly the polychrome ivory pyxis from San Pedro de la Rúa de Estella (fig. 7), which is preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It is dated to the 6th century and bears an unmistakably Eucharistic topic which is the multiplication of the loaves, and Christ enthroned between St. Peter and St. Paul, a common image in tabernacles until the 17th century.

There is a relatively remarkable quantity of 13th century cylindrical pyxides of Limousin enameled copper, many collected in museums around the world, as well as other boxes of the same shape made of ivory, now catalogued as pyxides or reliquaries. Many of these rich and sumptuous boxes, some made in Byzantine or Cordovan workshops and dated from the 6th to the X century, have a documented use in inventories as reliquaries. But seeing the numerous documentary references that speak of small ivory boxes to keep the Eucharist, and noting that the terms 'tabernacle' and 'reliquary' have been synonymous for centuries, it can be assumed that during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries these containers were commonly used for the Blessed Sacrament, either placed above the altar and also suspended over it from the baldachin or a suspensory designed for it, and that later -maybe from the fifteenth-sixteenth centuries- they have been reused as reliquaries. The enameled copper workshops of Limoges may have responded to the demand in the 12th-13th centuries by producing pyxides, Eucharistic boxes such as those mentioned above, and also Eucharistic doves, another interesting type of medieval tabernacle. Although none have been preserved in Navarre, there are examples in El Burgo de Osma, the monastery of Silos and in several museums, both Spanish and international, from private collections.

Judging by the number of medieval niches that populate the headers of many European churches, it can be affirmed that this was the most common way of guarding the Eucharist from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century. These mural tabernacles are found on the gospel side of the presbytery, on one side of the high altar and close to it, and can range from simple cupboards opened by an arch, to showy niches of micro-architecture in relief and with their own iconographic programs. They are always made of stone and are closed with a key and a wooden or, preferably, metal door, which often boasts rich artistic grillwork. A few have preserved the polychromy that we know they had, and there are even those that maintain the interior polychromy, consisting of a blue sky with gold stars or applied brocades, or images such as Christ the Savior, Calvaries or angels holding chalices with the Blessed Sacrament.

Although the oldest reference letter to a wall tabernacle dates from 1181, this subject of the tabernacle spread when the IV Lateran Council, celebrated in 1215-1216, regulated that the Blessed Sacrament should be kept in a safe place and under lock and key to avoid profanation. Numerous Hispanic synods replicated this order, as is the case of the synods of Calahorra-La Calzada in 1240, of Huesca in 1253, of Segovia in 1325, of Tarazona in 1354 or of Salamanca in 1410, among others. Even the deeds of Alfonso X Wise explicitly indicate that the Holy Sacrament should be "in a clean and section place and that it should be locked with a key, in such a way that no one could take it to harm it" (deed 1, law 60). Drilling the wall of the presbytery and creating a Closed niche with a sturdy door to put in it the eucharistic pyxes and chests had to be the safest and most economical way for many parishes.

In Navarra, the work to locate and study all the medieval mural tabernacles is still unfinished, and it is more than likely that in the next few years more cases and more documents about them will appear. But this is not an obstacle for not knowing some interesting specimens that we want to show in this selection.

Fig. 8. Mural tabernacle of the parish of the Assumption of Our Lady of Ollobarren. Photo: Aintzane Erkizia.

Mural tabernacle of the parish of Santa María del Pópulo de San Martín de Unx, from the parish of Ascensión de Otano. Circa 1500. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

Among the simplest is the Ollobarren tabernacle (fig. 8), which consists of an almost square niche, very simple and very repainted that resists the weather with a sturdy door of crossed iron bars. The one in the parish of Otano, now moved to the parish of Santa María del Pópulo de San Martín de Unx (fig. 9), is an ogee arch with Elizabethan balls that also conserves a grille of crossed pieces that could be dated around 1500.

Fig. 10. Mural tabernacle of the parish of the Assumption of Our Lady of Urroz-Villa, from the parish of Santiago de Galdurotz. Early 16th century. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

Fig. 11. Mural tabernacle of the parish of San Esteban de Alzuza. Circa 1510-1520. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

The niche that comes from the Galdurotz depopulation and is reused in the parish of Urroz-Villa (fig. 10), on the side wall next to the baptismal font, has a somewhat greater presence. The arch that frames the door has crude reliefs of birds, fish and fleur-de-lis, while at the base there is a simple vegetal scrollwork. Two very geometric heads function as brackets for the large voussoirs that frame the whole piece. The Alzuza tabernacle (fig. 11) is very similar in design, since it also has two corbels with anthropomorphic heads and a similar structure. On this occasion, the profile of the hollow is mixtilinear, which allows us to date it to around 1510-1520. Birds with fruit that looks like grapes could be an iconographic motif alluding to the Eucharist or paradise, but the fact is that the niche is decorated superficially with a few bouquets, flowers and six-petal roses, and a small cross over the door. This one in Alzuza remains in its original place on the Gospel side and, seeing that in the center of the altarpiece there is a gilded wood tabernacle with beautiful polychromy from the end of the 16th century, there is no doubt that it ceased to be used as a tabernacle after the implementation of the Tridentine decrees.

Gothic mural tabernacle of the parish of San Esteban de Genevilla, with part of its main altarpiece. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

Fig. 13. Mural tabernacle embedded in the cloister of the Royal Collegiate Church of Santa María de Roncesvalles. Photo: Aintzane Erkizia.

An interesting niche is the one in Genevilla (fig. 12). Although it preserves neither the door nor the polychromy, which undoubtedly gave it color and visibility, it is a good example of how these medieval type tabernacles were replaced by other wooden micro-buildings when the great Renaissance altarpieces were built. The magnificent 16th century altarpiece does not hide the niche, but covers part of its space. In spite of being a linteled opening framed by several successive ogee arches without decoration, this old tabernacle stands out for being framed by a wide and voluminous alfiz with Elizabethan balls, being the only Navarrese example with these characteristics, at least that is known so far.

But there are also some artistically more suggestive niches, with more elaborate architectural designs. One of them is located in a wall of the cloister of the Collegiate Church of Roncesvalles (fig. 13). Although it is full of dirt, very damaged, decontextualized and practically unpublished, a fine Gothic design can be seen, flanked by two spires and with a finial with long blind windows, very common in European late Gothic, as well as two erased heraldic coats of arms that would provide valuable information for its interpretation.

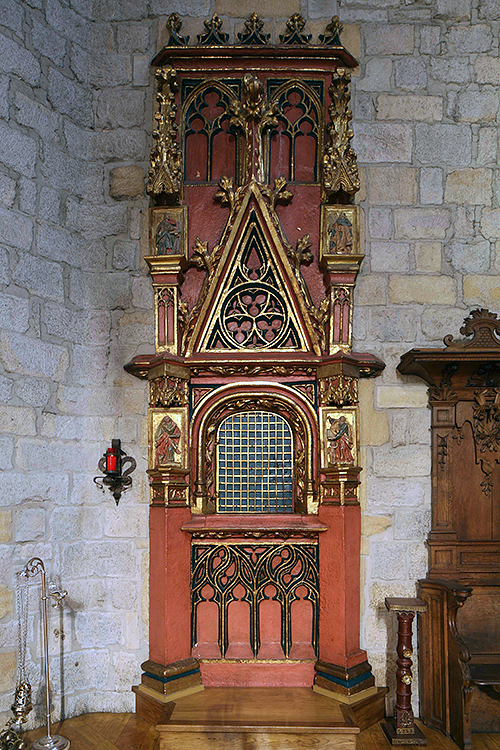

Fig. 14. Mural tabernacle of the parish of San Nicolás de Pamplona. First half of the 15th century. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

Another highly suggestive mural tabernacle is found in the parish of San Nicolás in Pamplona, which, for aesthetic reasons, could be dated to the first half of the 15th century (fig. 14). Once again, the tabernacle has been heavily intervened in that it is covered by a thick layer of plaster, totally repainted and disfigured, and Romanesque wooden reliefs have been added, mutilating the Gothic tabernacle. It is possible that, in its origin, apart from a very different polychrome, it had some small stone carvings that would make up its iconographic program. In spite of this state, it is one of the best tabernacles of Navarre and the largest of the mural tabernacles with its more than two meters of height.

Fig. 15. Fragment of the mural tabernacle of the cathedral of Santa María la Mayor de Tudela. Circa 1400. Museum of Tudela. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

In the cathedral of Santa María la Mayor de Tudela (fig. 15), during the archaeological excavations of 2002-2003, a fragment of a tabernacle was recovered that had been reused as a support for the baptismal font, and at one point in history, buried under it. It must be the old tabernacle of the cathedral, a niche of considerable size dated around 1400, probably removed in the Counter-Reformation period. It is the only Gothic tabernacle in Navarre that has a registration around the door, and that makes it one of the most interesting pieces in Navarre. The Gothic letters read: "[Verbum caro] panem verum : verbo carnem eficit : fitq[u]e sanguis xpi merum : et si se[nsus deficit]", words that belong to the Eucharistic hymn par excellence, graduate PangeLingua and traditionally attributed to St. Thomas Aquinas, the great scholastic theologian who expounded the doctrine of transubstantiation in the 13th century. The phylactery held by the two angels incensing the Eucharist has been erased and is unintelligible, as has almost disappeared the polychrome that it undoubtedly had. The two angels have a somewhat rough Anatomy , but the sculptor has paid attention to the carving of the details and the vegetal scrolls, some bas-reliefs of great finesse.

Fig. 16. Mural tabernacle of the parish of San Nicolás de Arteaga. Photo: Aintzane Erkizia.

Fig. 17. Mural tabernacle of the parish of Santa María de Abárzuza. Photo: Aintzane Erkizia.

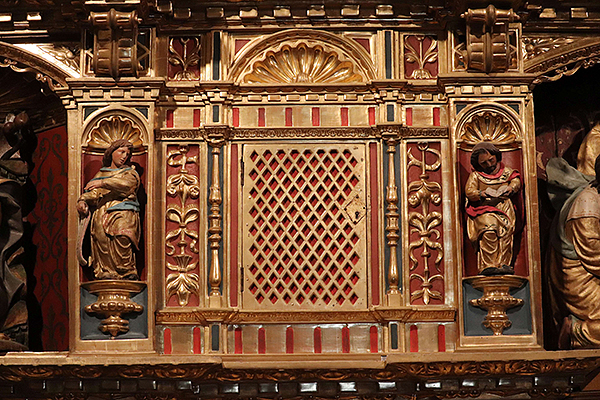

Finally, it is worth mentioning a few mural tabernacles made in the 16th century that, although they update their aesthetics to the artistic language of the Renaissance, belong to this typology of purely medieval tabernacles. The small niche of Arteaga (fig. 16) is a good early Renaissance piece, whose appearance is deformed by a thick repainting. The opening, square and Closed with a translucent grille, is already configured in "Roman" style, with flat pilasters with candelieri decoration. At the top is a chalice flanked by avolute scrolls typical of the early Renaissance. From the same group is the niche of Abárzuza (fig. 17), which stands out for its beautiful iron door. The deep intervention prevents us from knowing what its original form was like, but the putti, the goblets and the plants that it preserves undoubtedly belong to this context.

Fig. 18. Mural tabernacle of the parish of San Román de Larraya. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

Fig. 19. Head of the parish of San Antón Abad de Egiarreta. Photo: Aintzane Erkizia.

Fig. 20. Detail of the tabernacle of the main altarpiece of the parish church of San Antón Abad of Egiarreta. Photo: Aintzane Erkizia.

Some decade later, the Larraya tabernacle must have been sculpted (fig. 18), repolychromed in recent times, which could perhaps be considered the last mural tabernacle to be built in Navarre. The volumetric balustraded columns that frame it, the employment of classicist language and the tondo with the pelican are indicators of a late chronology for this subject of tabernacle, perhaps around 1550. This chapter closes with the Egiarreta tabernacle (fig. 19), which stands as a singular example of how some Renaissance altarpieces incorporated into their structure not a new wooden tabernacle on the central axis, but the old mural tabernacle on the gospel side, as in Dueñas (Palencia). The magnificent altarpiece was built from 1540 and one of the coffers of the first body integrates the mural tabernacle (fig. 20), flanked by two evangelists and crowned by a venera. This lateral location of the tabernacle lasted until 1635, when a new one was built in the center at the insistence of the episcopal visitors.

With them we see that the mural tabernacle of the Age average lasted a few decades beyond the end of the Gothic period until the Tridentine reform put an end to them. The epilogue of this medieval typology in Navarre were these Renaissance works that coexisted with the free-standing wooden tabernacles placed over the altar that were already being built, belonging to another conception of sacred space, more modern.

The Eucharistic towers can be considered as the best artistic manifestation of the furniture to keep the Blessed Sacrament, due to their outstanding size and their careful artistic attention. Their existence is almost as old as the internship to preserve the Eucharist, because the first news we have of them is the description of the tower that the emperor Constantine gave to one of the major basilicas of Rome, made of gold and decorated with precious stones. Its presence goes through many centuries in inventories, descriptions and liturgical texts, although there are hardly any copies preserved prior to the 14th century.

The shape of the tower has a great symbolic charge as an image of strength and security, but it has been employee in the Eucharistic receptacles because it recalls the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, and so it appears constantly in liturgical and theological literature. The direct association of the Sepulcher of the Lord with the tabernacle, both spaces used to deposit the body of Christ, has made this piece of furniture to use for centuries an architectural form, specifically the form of a building with a circular or central plan, inside which the body of Christ is kept wrapped in cloths that make reference letter the holy shroud, as happens with the aforementioned pyxides.

These towers met a great development in the Netherlands and Germany, where the best examples are to be found. They are called Sakramenthäuschen (little sacrament house) and are showy micro-architectures of enormous artistic depth made of durable materials such as stone, which had a great structural and artistic development from ca. 1300 until the Lutheran Reformation in some places and until the Tridentine Reformation in others. To a lesser extent we also find them in France and Scandinavia, generally of smaller size, and rarely in the rest of Europe, except for a concentration of Gothic Eucharistic stone towers that can be found precisely in the Basque Country, Navarre and Burgos.

Eucharistic tower of the parish of San Román de Metauten. Around 1500. Museum of Navarre, Pamplona. Photo: Aintzane Erkizia.

The best Eucharistic tower in Navarre is from Metauten (fig. 21) and is in the Museum of Navarre in Pamplona. It may not be the finest Gothic work in Navarre, but it is the one that has been preserved almost complete and represents a family of Gothic tabernacles that have disappeared with hardly a trace. For this reason it deserved to be the piece of the month of November 2022 in this same Chair and we had the opportunity to highlight it.

Fig. 22. Fragment of the tabernacle of the parish of Santa Eulalia de Ganuza. Circa 1520. Diocesan Cathedral Museum of Pamplona. Photo: Aintzane Erkizia.

Near Metauten is Ganuza (fig. 22), another small nucleus that must have had its stone tabernacle removed at the same time. Fortunately, its central body is preserved in the refectory of Pamplona Cathedral. It could be dated to the first third of the 16th century, because it is already made in Renaissance language typical of the beginning of this century, as indicated by the fine grotesques and the little cherub heads at the base. The body is square and it is possible that, even if it was Exempt, it was leaning against the wall of the presbytery, as is seen in other nearby cases. The front sample shows the face of Christ flanked by two angels carrying candles. On the sides, St. Peter and St. Paul act as witnesses to the Eucharist, an iconography that is almost general in Renaissance tabernacles.

Eucharistic tower of the parish of San Salvador de Arróniz. Circa 1500. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

Arróniz (fig. 23) has the third Eucharistic tower in Navarre, now located outside the church, in the open, very deteriorated. It is a free-standing tower raised on a fasciculated column that could be dated around 1500. The body of the tabernacle, possibly hexagonal in plan, has large Gothic tracery on each side in relief. Although it is missing half of the central body, the entire upper body and all traces of polychromy, and is so damaged by time, it is a silent witness to the existence of a group of stone towers in Navarre.

Perhaps the most significant Navarrese contribution to the landscape of European Eucharistic towers is a valuable documentary reference letter that reveals many of the characteristics of these works that we can no longer contemplate. It is the visit that in June 1501 Juan de Ortega, bishop of Calahorra-La Calzada, made to the parish of Torralba del Río, then belonging to his diocese. The bishop wrote that "he visited and found the corpus xpi [christi] in a new reliquary of carved stone of masonry in the manner of a tower of very good stone, which is not yet well finished, on the left hand side of the main altar". In the following years payments are recorded to Master Oliver for making this tabernacle, and in 1506, the Provisor who revisits the church sees the "new gilded stone reliquary". These two mentions, as brief as they are substantial, provide some very revealing data : they give a clear date of construction of these Eucharistic towers around 1500; they speak of the care that was taken with the stone, selected for its quality; they confirm that the towers were located on the gospel side, like the mural tabernacles; they reaffirm that the tabernacles were gilded and polychromed; and they notify the architectural conception of these works, a characteristic that defines them and integrates them into the genre of micro-architecture. In this way, this documentary quotation corroborates what can be concluded from the study of the tabernacles that have survived the modern era and, at the same time, financial aid to interpret the numerous stone fragments that we find in many parishes.

The niches and towers are physically separated from the high altar, but they are always located in the presbytery and, as such, are an indispensable component of the medieval liturgical setting and part of the altar equipment. However, it has already been pointed out that the Eucharist is also placed on the high altar itself, in chests, boxes and pyxides, or suspended from the baldachin. The link between the altar as table of sacrifice and commemoration of the supper and the tabernacle has been constant and, for this reason, after several centuries in which the tabernacle could be placed in the presbytery, the Tridentine reform prescribed a single location of the tabernacle in the center of the high altar and fixed to it. The Spanish synodals from the middle of the 16th century onwards already made clear this new rule, written by reformist and humanist bishops who had attended the ecumenical council, such as those of Astorga in 1553, Guadix in 1554, Salamanca in 1565 or Burgos in 1577.

In Navarre, the reforming zeal of its bishops allowed the reform to be applied before the celebration of the Council of Trent. From 1540, under the episcopate of Pedro Pacheco, there were already orders from visit that ordered the construction of wooden tabernacles to be placed on the altar, although this rule was only applied in parishes that did not have a tabernacle; where visit had wall tabernacles, it considered them adequate, and in other places it even ordered the construction of a cupboard in the wall so that the pyx could be kept safely. It was in the second half of the century when men like Master Martín de Miranda or Doctor Alquiza, both titled "visitador and reformer" visited the diocese and systematically ordered the systematic removal of all the stone tabernacles, both towers and niches, declared inadequate because they were obsolete and separated from the altar. Thus began the relentless disappearance of the medieval tabernacles of Navarre.

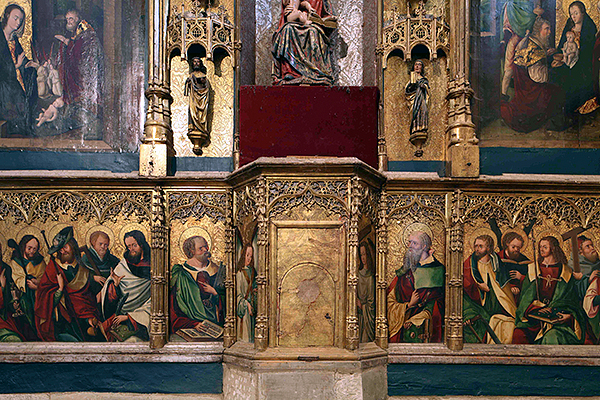

Fig. 24. Bench and first body of the altarpiece of the parish of the Assumption of Our Lady of Marañón. Early 16th century. Photo: Justin Kroesen.

Something that must be emphasized in this historical process is that these new Tridentine prescriptions had a medieval antecedent, not only with the chests and pyxides placed on the altar, but above all with a subject of tabernacle that developed in the Crown of Aragon from the middle of the 14th century, when altarpieces of stone, wood or painting of a certain entity began to be built. These Gothic altarpieces have a wooden tabernacle supported on the altar, made with an architectural structure and complemented with images that allude to the Eucharist, just as Renaissance tabernacles would be. Certainly, in the synods of Barcelona (1241), Tarragona (1242), Valencia (1258), Barcelona (1347) and many others, it was already ordered that the tabernacle should be in the center of the main altar, something that hardly occurred in other geographies and, therefore, from the second half of the 14th century, in the Crown of Aragon the altarpieces were already built with a tabernacle, thus anticipating the Renaissance and the Tridentine tabernacles.

It is undeniable that Navarrese art participates in the genres, artists and artistic tendencies of Aragon and, although it hardly develops this subject of the Gothic wooden tabernacle over the altar, it does have an example that represents it masterfully, which is the tabernacle of the parish of Marañón (fig. 24). The altarpiece and the tabernacle form a whole made within the late Gothic style of the early 16th century, and the Eucharistic box, integrated in the predella, stands out from the surface of the altarpiece because it has a trapezoidal shape, emulating a tower with a hexagonal central plan as a representation of the Holy Sepulcher.

The front has been intervened and has lost the original image, but the good preservation of the rest of the altarpiece shows that the iconographic program is also unitary. Thus, the tabernacle, with two angels carrying the cross and a crown of thorns, is flanked by St. Peter in the hand of the Gospel and St. Paul in that of the Epistle, accompanied in turn by the apostolate. Above the tabernacle is the titular of the temple, a carving of the Virgin and Child surrounded by the evangelists, and above it the Assumption marks the path of Salvation that culminates with a Calvary. This organization of the message will be the most common in the major altarpieces that will be built from this moment on, whose axis will always be structured around the tabernacle.

Another case worth mentioning here is the old main altarpiece of the parish of San Miguel de Barillas, in the merindad of Tudela, which belonged until the 18th century to the diocese of Tarazona. The main altarpiece, dedicated to Saint Michael and paid for by the lords of Barillas around 1470 and attributed to the circle of Jaume Huguet, does not preserve its original tabernacle, but the hollow in the center of the predella is evidence of its existence, very early in Navarre, but very common in Aragon.

As a culmination to this tour through the medieval tabernacles of Navarre, it is necessary to emphasize that this rich Navarrese heritage is positioned as a crossroads and a meeting point between Castile, Aragon and France. This is visible in all the artistic production, and also in the typologies and forms of the medieval tabernacles: the Limoges enamels come from France, the niches and towers coincide with the Spanish landscape, and some Gothic tabernacles over the altar share the Aragonese custom. Medieval tabernacles are artistic pieces with an evolution and forms determined by their function, and are loaded with a rich symbolism that has determined their form, demonstrating that in the history of art, form and content go hand in hand. The landscape of medieval tabernacles in Navarre is a good sample of this.

This section lists a selection of the fundamental publications on the history of the tabernacle, including works that analyze this artistic piece of furniture in general. It does not include, therefore, programs of study of case or specific bibliography , which is very broad.

AIZPÚN, J., "El retablo mayor romanista y el sagrario. El 'Oriente' del espacio de culto cristiano", FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R. (coord.), Pulchrum. Scripta varia in honorem M.ª Concepción García Gainza, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, University of Navarra, 2011, pp. 43-50.

AYALA LÓPEZ DE CONTRERAS, J. (Marqués de Lozoya), "Sagrarios mudéjares", Revista Nacional de Education, n.º 1, 1941, pp. 51-53.

DIX, G., A Detection of Aumbries with other notes on the History of Reservation, Westminster, Dacre Press, 1944.

ERKIZIA-MARTIKORENA, A. and KROESEN, J., "A Temple in a Temple. Medieval Tabernacles on the Iberian Peninsula", RODOV, I. M. (ed.), Enshrining the Sacred: Microarchitecture in Ritual Spaces, New York, etc., Peter Lang, 2022, pp. 135-176.

ERKIZIA-MARTIKORENA, A., "El sagrario como referente simbólico del Santo Sepulcro", La Orden del Santo Sepulcro. VIII conference Internacionales de Estudio, Zaragoza, Centro de programs of study de la Orden del Santo Sepulcro, 2019, pp. 55-70.

ERKIZIA MARTIKORENA, A., "El sagrario en el equipamiento del altar medieval en la corona de Castilla. Some methodological reflections", Codex Aquilarensis, n.º 38, 2022, pp. 255-272.

ESPAÑOL BERTRÁN, F., "Tabernacle-retables in the Kingdom of Aragón", KROESEN, J. and SCHMIDT, V. (eds.), The altar and its environment 1150-1400, Turnhout, Brepols, 2009, pp. 87-108.

FOUCART-BORVILLE, J., "Essai sur les suspenses eucharistiques comme mode d'adoration privilégié du Saint Sacrement", Bulletin Monumental, no. 145-III, 1987, pp. 267-289.

FOUCART-BORVILLE, J., "Les tabernacles eucharistiques dans la France du Moyen ge", Bulletin Monumental, no. 148, 1990, pp. 349-382.

GARCÍA GAINZA, M.ª C. (dir.), Catalog Monumental de Navarra, Pamplona, Institución Príncipe de Viana, 1980-1997, 9 vols.

GERMAN, K., Sakramentsnischen und Sakramentshäuser in Siebenbürgen, Petersberg, Imhof, 2014.

GOÑI GAZTAMBIDE, J., Los navarros en el Concilio de Trento y la reforma tridentina en la Diócesis de Pamplona, Pamplona, Imprenta diocesana, 1947.

ÍÑIGUEZ ALMECH, F., "The tabernacle. Some early Spanish forms and their transformations", XXXV International Eucharistic congress . The Eucharist and Peace. Barcelona: [s.n.], 1952, volume I, pp. 824-825.

KING, A., Eucharistic Reservation in the Western Church, New York, Sheed and Ward, 1965.

KROESEN, J. and TÅNGEBERG, P., Die mittelalterliche Sakramentsnische auf Gotland (Schweden). Kunst und Liturgie, Petersberg, Imhof, 2014.

MAFFEI, E. La réservation eucharistique jusqu'à la Renaissance, Brussels, Vromant, 1942.

TIMMERMANN, A., Real Presence: Sacrament Houses and the Body of Christ, c. 1270-1600, Turnhout, Brepols, 2009.

VAN DIJK, S. J. P. and HAZELDEN WALKER, J., The Myth of the Aumbry. Notes on medieval reservation practice and eucharistic devotion, London, Burns & Oates, 1957.